Framing history in early Princeton

by The Frame Blog

Elizabeth Baughan and Karl Kusserow tell the fascinating story of a frame and its conservation: a frame which held successively the portrait of the king of Great Britain and the first president of the USA.

This article was first published in PRINCETON UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM Record, Volume 70 / 2011.

Charles Willson Peale, American,1741–1827: GeorgeWashington at the Battle of Princeton, 1783. Oil on canvas, 237 x 144.9 cm. Commissioned by the Trustees, Princeton University (PP222). In royal trophy frame, ca. 1760, attributed to René Stone, British, d. 1773/4. Gilded sugar pine, 268.6 x 177.8 cm. Restored in 2009–10 through the generosity of William Neidig, Class of 1970, and Christy E. Neidig, in memory of Lorenz E.A. Eitner, Graduate School Class of 1952. Photo: Bruce M.White.

Figure 1. Attributed to René Stone, British, d. 1773/4: Royal trophy frame, ca. 1760. Gilded sugar pine, 268.6 x 177.8 cm. Restored in 2009–10 through the generosity of William Neidig, Class of 1970, and Christy E. Neidig, in memory of Lorenz E. A. Eitner, Graduate School Class of 1952.

At the beginning of January 1761, a large box containing an elaborately framed (fig. 1), full-length portrait of England’s King George II arrived at the College of New Jersey in Princeton, transported south from Elizabeth by one Daniel Price, who was paid for his efforts with more than twice the amount received by George Price, his presumed relative, for making the box. The bill for the transaction, dated January 8, is addressed to Samuel Woodruff, mayor of Elizabeth and a trustee of the fledgling Princeton College [i].

The royal portrait was immediately installed in the prayer room of Nassau Hall, the central space in the college’s recently completed home, then perhaps the most impressive building in the colonies (figs. 2–3). The painting’s sudden appearance in Princeton seems due to formal exercises on January 14 to mark the death of George II, who had passed away in London several months before and in whose name the school had been granted its charter. The ceremony included two orations, both subsequently published, by esteemed Presbyterian divines Samuel Davies, president of the college, and Samuel Blair, his erstwhile teacher. Blair’s eulogy refers directly to the portrait, lamenting “that thine Image should yet attract our Eyes, if its more admired Original be obscured in Death!,” as does his An Account of the College of New-Jersey (1764), suggesting the significance attached to the newly acquired picture. While its renown proved to be short-lived—it was destroyed in 1777 during the Battle of Princeton—the frame surrounding it has endured the ravages of war, reuse, fire, and time to become, precisely on account of them, among the most storied in American art. Its recent inclusion as a central feature of the exhibition Inner Sanctum: Memory and Meaning in Princeton’s Faculty Room at Nassau Hall (2010) was the occasion for a painstaking restoration, prompting research of the frame’s compelling history. This article describes each [ii].

Although the portrait of George II occupied Nassau Hall’s prayer hall for only sixteen years, it was a singular fixture while there. The otherwise Spartan room was in keeping with the chaste dictates of the fervent “New Side” Presbyterians who founded the school. As President Davies’s predecessor, Aaron Burr Sr., noted with reference to Nassau Hall, “We do everything in the plainest & cheapest manner, as far as is consistent with Decency & Convenience, having no superfluous Ornaments.” Apart from what Blair’s Account describes as a “neatly finished front gallery . . . [and] a small tho’ exceeding good organ,” little else embellished the hall beyond the royal portrait and, across the room from it, a surely less grand portrayal of the sympathetic colonial governor, Jonathan Belcher, and his family coat of arms. The courtly trappings of a formal state portrait and its lustrous gilt frame must have appeared both remote and conspicuously luxurious to the students gathered in the lamplight of the hall for mandatory predawn prayers [iii].

Figure 2. Nassau Hall, from The New American Magazine, March 1760, engraving by Henry Dawkins (active 1753–1786). Nassau Hall Iconography, University Archives, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Figure 3. Nassau Hall plan, from Henry Lyttleton Savage, Nassau Hall: 1756–1956 (arrow indicates north).

It remains unclear who authorized the transfer of the portrait to Princeton and whence, exactly, it came. Samuel Woodruff’s appearance on the invoice for its removal from Elizabeth might seem to implicate his friend, Governor Belcher, as early historians of the school have proposed. However, Belcher died in 1757, and the 1755 deed of gift conveying to the college his own portrait, books, and other carefully enumerated contributions makes no mention of such a donation, nor does his will contain a reference to one. What is known is that commissions were made in England for portraits of the king to be sent to Belcher’s two successors as New Jersey’s colonial governor, Francis Barnard and Thomas Boone. These were granted on January 30, 1758, and December 12, 1759, respectively; the portraits that resulted would have been painted by John Shackleton (d. 1767), the king’s official portraitist, and their frames produced by René Stone (d. 1773/4), his appointed framemaker [iv].

Figure 4. John Shackleton, British, d. 1767: King George II, 1762. Oil on canvas, 231.1 x 147.3 cm. In frame by René Stone, completed 1766. British Museum.

Shackleton was sworn “into the place and quality of Principal Painter in Ordinary to His Majesty” in 1749, the twenty-second year of George II’s reign. He held the position until the king’s death in 1760 and for several years after, continuing to produce portraits of the deceased monarch and other nobility even following the 1761 appointment, in an unusual dual incumbency, of Allan Ramsay as “One of His Majesty’s Principal Painters in Ordinary.” In 1762, Shackleton completed a portrait of George II for the British Museum (fig. 4), commissioned by that institution in gratitude for the late monarch’s establishment of a library there. Subsequently, according to the minutes of the museum’s trustees, it was “Ordered, That Mr. Stone do prepare a frame for the Picture of His late Majesty according to the drawing laid before the Committee by Mr. Shackleton.” Assuming the portrait that arrived in Princeton the preceding year was one of those originally intended for governors Barnard or Boone, it follows that the appearance of the British Museum painting, commissioned from the same artist and framemaker within a few years of it, corresponded closely to the college’s lost picture. Shackleton, as the king’s official image-maker, produced a steady stream of highly similar depictions of the monarch; between 1748 and 1760, twenty-one warrants were issued by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office for “whole length portraits of His Majesty to be executed by his Principal Painter,” many destined for such colonial outposts as New Jersey. Certainly, the surviving frames are remarkably similar, the only significant difference between them being the absence atop the Princeton frame of the carved openwork crown [v].

Whatever the details of the Nassau Hall portrait, when, on January 3, 1777, the canvas “was torn away by a ball from the American artillery in the Battle of Princeton”—as the event was recorded in the minutes of the college trustees—it was an incident fraught with symbolism only compounded by the recollection of Ashbel Green, Class of 1783, who wrote, “There is testimony which is accredited, that the shot took off the king’s head.” While the painting was lost, the ornate frame surrounding it—a rarity in colonial America— was salvaged and initially repurposed to hold the coat of arms of the late Governor Belcher, whose portrait had also been destroyed in the conflict [vi].

As the school gradually repaired the damage wrought upon Nassau Hall by the war (so extensive that diarist Ebenezer Hazard observed, “every room in it looks like a stable”), Princetonians could hardly have envisioned that the next group to occupy the building would be the Congress of the Confederation, as the American government was formally known, which took up residence from June to November 1783, reserving the prayer hall—still housing the frame—for official functions. A highlight of their tenure was the reception in that space of General Washington himself, who attended the school’s September 24 commencement exercises. The following day, the college’s leaders, “being desirous of giving some testimony of their high respect for the character of his Excellency General Washington,” and wishing to honor his presence in their midst, appointed “a committee to wait upon his Excellency to request him to sit for his picture to be taken by Mr. Charles Willson Peale of Philadelphia.” Washington granted Peale the fifth of his unsurpassed seven sittings in December 1783. The resulting portrait, George Washington at the Battle of Princeton (fig. 5), was completed by the following commencement and probably installed in the prayer hall personally by Peale, who wrote, “I painted a picture of Genl. Washington for Prince Town Collidge and was at the Commencement, much Entertained.” [vii]

Figure 5. Charles Willson Peale, American, 1741–1827: George Washington at the Battle of Princeton, 1783. Oil on canvas, 237 x 144.9 cm. In frame attributed to René Stone (pre-conservation). Portrait commissioned by the Trustees, Princeton University (PP222).

It is not known whether the college dictated the terms of the picture’s appearance, but it must have been expected that Peale would produce an image of the decisive local engagement in which he had fought, in which the college was heavily implicated, and during which Washington had especially distinguished himself for bravery. What seems certain is that Peale was requested to make a portrait sized to fit the frame of the ruined George II. Evidently the trustees associated the one portrait with the other, for in authorizing the creation of Peale’s painting they specifically “ordered that his portrait, when finished be placed in the Hall of the College in the room of the picture of the late King of Great Britain.” By electing to insert the new painting in the frame—both literal and figurative—of the old one, they added another layer of symbolism to its eventful history, at the same time providing a rationale for its own “decapitation,” like the picture it once surrounded, with the removal of its central design feature: the king’s crown [viii].

While it is usual that a frame complement a painting aesthetically, it is rare that it also add multiple dimensions of historical and conceptual meaning to the work it both protects and enhances. There is a remarkable symbolic narrative to the displacement of the portrait of George II—by 1777 as unwelcome an occupant of the prayer hall as the British soldiery—with the portrait of another George, who led the battle that destroyed the first painting and whose image sup- planted, in the very frame, that of the monarch—and did so in a depiction of the actual victorious event. Few works of art are so elaborately involved in their own history.

Partially as a result of their meaningfully intertwined pasts, the painting in its frame enjoyed iconic status at the college and beyond. As early as 1787, the Reverend Manasseh Cutler, visiting from Massachusetts, singled the picture out for detailed description in his account of the college hall, with which he announced he was “quite pleased.” Portrait and frame escaped damage in the calamitous fires that gutted Nassau Hall on March 6, 1802, and again on March 12, 1855, when students and faculty, “eager to rescue the portrait of Washington by the elder Peale,” forced the door to the room open and brought them “without injury to a place of safety.” Apart from these required evacuations, the painting left Nassau Hall only twice before eventually being moved to the Princeton University Art Museum (in 2005) for reasons of accessibility and protection. In 1824, in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette’s visit to Princeton to receive an honorary degree, a temple-like structure was erected on the front campus, with the Washington portrait prominently displayed (the marquis said he thought it an excellent likeness of the general when he first knew him).

Figure 6. Princeton exhibit at the World’s Colombian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. University Archives, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Nearly seventy years later, the painting traveled to Chicago, where, with an American flag draped around the frame, it formed the centerpiece of Princeton’s exhibit at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (fig. 6).

Figure 7. E. M. Museum, College of New Jersey. Princeton Historical Society.

Figure 8. Unknown artist, after Godfrey Kneller, British, 1646–1723: King George II, ca. 1727–32. Oil on canvas, 242.3 x 153 cm. Princeton University, gift of members of the Classes of 1894 and 1919 (PP2).

Although the portrait remained otherwise in place in Nassau Hall—denied removal for additional exhibitions, which might have jeopardized its safety—the space around it evolved from prayer hall to college library to, in 1874, Princeton’s museum, featuring an unlikely installation with Washington facing the school’s famed Hadrosaurus Foulkii (fig. 7). Upon the opening of University President Woodrow Wilson’s redesigned Faculty Room in the same space in 1906, the picture took a more congenial place among images of the institution’s founders and leaders—including, eventually, another portrait of George II, donated in 1936 by historically minded alumni and hung on the opposite side of the President’s desk (figs. 8–9). In each of its various installations, Peale’s portrait in its celebrated frame has been venerated for its rich embodiment of a history that is not only local and institutional but also national, a status reflected in a 1908 press release issued by the University pronouncing it “Princeton’s most treasured work of art.” [ix]

Despite its revered standing—or perhaps because of it— both painting and frame have remained relatively untouched in the more than two centuries since being united. Records indicate that the canvas was cleaned in 1847 and again in 1937, and slight damage repaired in 1974 and 2006, but apart from a single regilding, also in 1847, the frame had not been treated until the current restoration. It did not, how- ever, endure the vagaries of its long history unscathed, having sustained numerous losses to the wooden substrate (beyond the intentional removal of the crown) and the unfortunate effects of the 1847 regilding, which resulted in the obscuration of carved details in the wood and recarved gesso, and eventually in the wholesale cleaving and flaking of the gilded surface when its adhesive bond to the frame failed (fig. 10) [x].

Figure 9. Faculty Room, south wall, after 1936. Historical Photograph Collection, University Archives, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Figure 10. Frame detail, showing obscured carving and surface cleaving.

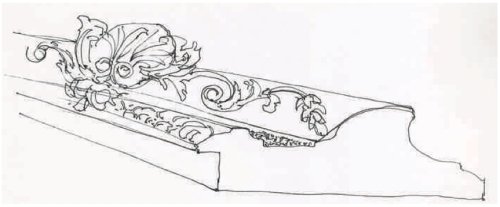

In order to determine the proper course of conservation treatment, the frame was assessed stylistically, its materials and techniques of manufacture identified, and its present condition examined. The frame is a fine example of a royal, early Georgian trophy frame created in the French manner. Also known as a corner-and-center or court frame, this style became popular in England during the first half of the eighteenth century and was commonly used for portraits, as the protruding corners and central shell cartouches characteristic of its design draw the eye to a full-length portrait’s compositional focal point, the sitter’s head (fig. 11). Often incorporating a flat, sanded frieze, scrolling tendrils, and, depending on the frame’s importance, heavily recarved gesso, the type is chiefly distinguished by the top member’s central trophy or “fronton” (from the French for “pediment”) element that lends the frame its name.

Carved from sugar pine, oil gilded, and measuring 1053/4 by 70 inches, the Princeton frame features a leaf-and-tongue running molding on the sight edge, followed by a fillet and sanded frieze; a half-round ending in the top rail leads to a back hollow and another running decorative tongue element prior to the back edge (figs. 12–13). The corners have scrolling foliage, and the running lengths of the two side and bottom members are punctuated by a centered stylized shell, flanked symmetrically by inverted, slightly smaller, realistic shells. Prior to conservation, the top member incorporated the fractured remnants of palm fronds made of composition, evocations of the wooden fronds originally cradling the central crown and likely added in preparation for Peale’s portrait, to visually mitigate the motif’s absence. Also likely at this time, the corner splined miters were cut, probably to resize the frame by a fraction in order to receive the Washington portrait. To rejoin the severed miters, large L-shaped iron anchors were added at the corners, an early American stabilizing technique for the joints of large or heavy frames [xi].

Extensive carved detail in the gesso was revealed in areas where loss of the 1847 overgilding was particularly pronounced (fig. 14), indicating both the frame’s high quality and the French influence informing its manner of production. In the French reparure technique used to recarve gesso, a gilder uses a rapid pulling motion with a hook-like iron carving tool, employing multiple hooks with differently shaped tips to create various patterns. This technique affords fluid details as well as a crispness in the final gesso surface, enhancing the refraction of light from the frame’s multiple surfaces and producing a desirable scintillating effect. Prior to the adoption of this technique in England, a carved and gessoed English frame would have been returned to the carver to recarve with his dissimilar tools, using a pushing motion that resulted in chisel marks, which were sanded out; alternatively, the gilding simply would have been applied directly on the smoothed, uncarved gesso.

Figure 11. George Washington at the Battle of Princeton in post- conservation frame.

Figure 12. Frame section detail.

Figure 13. Frame moulding profile. Drawing courtesy Kay Jackson and Bill Adair.

Like the design of the frame itself, derived from Louis XV prototypes, the craftsmanship of the Princeton frame is a direct reflection of the French Huguenots thriving in Great Britain. With the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, an estimated four hundred thousand Huguenots fled to Protestant countries such as Great Britain and the Dutch Republic. The Restoration of the English monarchy in Great Britain in 1660 created a stable economy well prepared to receive and employ these often highly skilled immigrants and their descendants, some of whom, René Stone among them, achieved the highest levels of success. Despite the British aversion to France and French objects, techniques and designs brought to England by the Huguenots or published in French pattern books were quickly incorporated into the English design vocabulary. As eighteenth-century British architect Isaac Ware commented, the French are “a frivolous people whom we are apt to imitate.” [xii]

Figure 14. Frame detail, showing extensively recarved gesso.

Following initial analysis of the frame, a stereomicroscope was used to more closely assess losses to the original surface. Examination under magnification confirmed that the cleaving systematically included the oil size and gold of both the primary and later regilding, but not the gesso. The visible gesso of origin appeared very largely intact, suggesting that the 1847 overgilding, however unstable ultimately, had served as a protective barrier for the gesso layer, a mere one- sixteenth of an inch thick in places. The realization that a high percentage of the original, elaborately recarved substrate might thus be recovered justified consideration of comprehensive dry stripping, as opposed to less invasive consolidation of the existing, later surface.

In conserving an object of such historical significance, one whose appearance, moreover, results from the very vicissitudes—war, fires, and time itself—for which it is renowned, the decision to remove the accretions of age cannot be taken lightly. While the overarching goal in restoring the frame was to improve its much-compromised aesthetic effect, doing so most effectively would simultaneously mean effacing a significant part of its physical history. The ultimate decision to remove the occlusive overgilding—and, necessarily, the primary gilding with it—was informed by the reality that in its pre-conservation state the frame had ceased to function effectively as an aesthetic object on its own terms and, as importantly, no longer reflected its principal intended function of bolstering the image of the personage it surrounded, be that George II or George Washington [xiii].

Figure 15. Fronton detail, pre-restoration, with broken composition palm fronds.

Conserving the central fronton posed its own unique set of issues. Given the political implications of the frame with the fronton intact—which doubtless accounted for its removal in the first place—it was impossible to consider crowning General Washington. Yet the coherence of the frame’s design and consequent aesthetic effect also had to be considered. The composition palm fronds in the area beneath the crown’s original location were poor copies of the originals, and moreover had at some point partially broken off (fig. 15).

Figure 16. Fronton detail, René Stone frame for King George II, British Museum (see Figure 4).

Figure 17. Fronton detail, William Kent frame for King George II, Rokeby Park.

Figure 18. Fronton detail, Gerrard Howard (attributed) frame for Queen Caroline, location unknown. Drawing courtesy Lynn Roberts.

Hence it was decided to remove these later additions and recreate the wooden fronds, but not the crown. In doing so, three contemporary models were studied: the British Museum’s King George II, with a René Stone frame; another portrait of King George II at Rokeby Park in County Durham, UK, with a frame by William Kent (ca. 1685–1748); and a portrait of George’s wife, Queen Caroline, currently unlocated but known through photographs, in a frame attributed to Gerrard Howard (1709–ca.1781), who preceded Stone as the king’s framemaker. While the Stone frame would seem the likely model for recreating the base of the fronton on Princeton’s frame attributed to the same maker, the British Museum example (fig. 16) has palm fronds gathered into a stem centered under the crown, whereas the Princeton frame (see fig. 15) features scrolling volutes like the Rokeby (fig. 17) and Queen Caroline (fig. 18) frames, apparently reflecting occasional slight variations in the design of frames produced by the same workshop.

Figure 19. Replacement carvings for Princeton frame.

Figure 20. Fronton detail, post-conservation.

Based on the existing footprint of the Princeton frame’s original fronds, Queen Caroline’s frame was selected as the closest model, and replacement carvings (fig. 19) were created, guided by its arching fluidity. The resulting fronton (fig. 20), though missing its crown, completes the visual experience of the frame and no longer distracts attention from the painting it surrounds [xiv].

In addition to the fronton, carvings were crafted to replace the other wood losses to the frame—notably the edges of the central shell motifs on each of the side and bottom members—which had been crudely recreated using composition. However, if a previous repair did not draw the eye, it was left alone. Carved fills were isolated with a barrier of Paraloid B72 (an acrylic, thermoplastic resin) before being attached. Traditional gesso was used for both small fills as well as the newly carved pieces, and the final coat was tinted with watercolor to approach, but not exactly match, the aged gesso, maintaining the distinction between the two [xv].

Figure 21. Corner detail, showing dry-stripped frame before and after gilding.

Once dry stripping was complete, the outstanding quality of the original carved wooden substrate and gesso—over ninety-five percent of which was recovered using surgical scalpels to remove the overgilding—became clearly apparent. In regilding the frame (fig. 21), reversible nontraditional gilding techniques were chosen. An acrylic resin (Plextol) was an ideal treatment for the Princeton frame, as it served as both consolidant and mordant and, because reversible, obviated the need for an additional, barrier layer. Although the original gesso was extremely strong as a substrate, its carved definition was at risk of being lost again if additional layers were added to it. The thickness of a single extra layer could also have obscured the subtle textures of the newly uncovered surface. An acrylic resin formula had the additional benefit of perfectly simulating gold size. A thin coat was floated on the frame and absorbed rapidly. The mere exhalation of breath was all that was required to activate the mordant; gold was laid and immediately tamped with cotton. The minimum humidity exhaled onto the frame produced an ideal simulated oil-gilded surface. This nontraditional technique often calls for a protective coat of acrylic varnish, Soluvar Matte. However, after modestly toning the frame with felted wool and watercolors, it was clear that the Plextol formula was sufficiently resistant and a protective finish unnecessary. The degree of toning sought to mediate between keeping the viewing experience of the venerable frame and painting plausible, in light of their age, and rein- vesting them with a measure of the freshness and vibrancy they originally projected.

Figure 22. George Washington at the Battle of Princeton in restored frame at gallery entrance.

Upon completion of the project, the frame was reunited with its occupant of the last two and a quarter centuries, and, as installed at the entrance to the Museum’s Mary Ellen Bowen Gallery of American Art (fig. 22), George Washington at the Battle of Princeton looks as if it has itself been restored, with the frame’s resplendent surface once again refracting light onto the renowned canvas with which it has for so long and compellingly been linked [xvi].

NOTES

[i] The invoice is preserved in the Pyne-Henry Collection of the Princeton University Library and is transcribed in V. Lansing Collins, “The Lost Portrait of George the Second,” Bibla 5, no. 1 (1934): 11.

[ii] Lest Blair’s oblique allusion to the portrait in his sermon be unclear, a foot- note in the published text advises readers that he is indeed “Alluding to the Picture of his late Majesty, in the College-Hall”; see Samuel Blair, An Oration Pronounced at Nassau-Hall, January 14, 1761; On Occasion of the Death of His Late Majesty King George II (Woodbridge, N.J.: James Parker, 1761), 6. Davies’s sermon appeared in multiple printings, including A Sermon Delivered at Nassau-Hill, January 14, 1761 on the Death of . . . King George II . . . (New York: J. Parker and Company, 1761). In later describing Nassau Hall’s prayer hall, Blair observed, “It is also ornamented, on one side, with a portrait of his late majesty, at full length.”; see An Account of the College of New Jersey (Woodbridge, N.J.: James Parker, 1764), 12. The Inner Sanctum exhibition was held in situ from May 28 through October 30, 2010, accompanied by a catalogue of the same title; see Karl Kusserow, ed., Inner Sanctum: Memory and Meaning in Princeton’s Faculty Room at Nassau Hall (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010). Restoration of the frame was generously under- written by William Neidig, a member of Princeton’s Class of 1970, which sponsored the larger exhibition project, and Christy E. Neidig, in memory of Lorenz E. A. Eitner, Graduate School Class of 1952.

[iii] Aaron Burr to William Hogg, December 3, 1755, Aaron Burr Collection, University Archives, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. Blair, Account, 12–13.

[iv] Blair’s Account, 12–13, contains the initial misinformation attributing the royal portrait’s presence at the college to Belcher; it is repeated in John Maclean, History of the College of New Jersey, at Princeton (1877; repr., n.p.: Lulu, 2006), 1:360. For Belcher’s actual gifts, including “all my Library of Books [totaling 474 volumes] a Catalogue whereof is hereunto affixed together with my own Picture at full length in a gilt Frame now standing in my blue Chamber also one pair of Globes and ten pictures in black Frames over the mantle Piece in my Library Room being the Heads of the Kings and Queens of England [these were smaller, bust-length depictions] & also my large Carv’d gilded Coat of Arms,” see Board of Trustees Minutes and Records, vol. 1, p. 45 ff. (September 25, 1755), University Archives, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library (hereafter abbreviated, “Trustees Minutes”). For the warrants authorizing portraits of George II for governors Barnard and Boone, see The National Archives of the UK: Public Record Office LC 5/162 (Records of the Lord Chamber- lain, Lord Chamberlain’s Department, Miscellaneous Records, Warrant Books, General, 1753–93). For information on Shackleton, see J. R. Fawcett Thompson, “The Elusive Mr. Shackleton: Light on the ‘Principal Painter in Ordinary’ to Kings George II and George II,” Connoisseur 165 (1967), 232– 39. On Stone, see National Portrait Gallery online catalogue, “British Picture Framemakers, 1630–1950,” s.v. “René Stone,” (accessed 30 June 2013).

[v] “Into the place and quality of Principal Painter” and “whole length portraits of His Majesty,” quoted in Thompson, “Elusive Mr. Shackleton,” 234 and 239. British Museum Trustees (Minutes of the Standing Committee, August 6, 1762), quoted in “Curator’s comments,” online record for Portrait of King George II (British Museum registration number: Painting.12), (accessed 30 June 2013).

[vi] On the Battle of Princeton, culminating in the American battery of the British stronghold in Nassau Hall, which the Redcoats had occupied, see Richard M. Ketchum, The Winter Soldiers: The Battles for Trenton and Princeton (1973; repr., New York: Henry Holt, 1999); and David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 324–45. Historians’ skepticism regarding the fate of the portrait is understandable. Describing the incident as “a legend long cherished in the college,” David Hackett Fischer has suggested that the painting was “more likely . . . attacked by an American infantryman with bayonet or sword” (ibid., 339). But the near-contemporary account of the trustees and Green’s recollection supports the story—although whether it was Alexander Hamilton’s artillery that fired the fateful shot, as has been claimed, is unclear. For the trustees’ account, see Trustees Minutes, v. 1, p. 236 (September 25, 1783). Green’s recollection is in his “Dr. Witherspoon’s Administration at Princeton College,” Presbyterian Magazine 4, no. 10 (1854): 470, where the information that Belcher’s arms replaced the king’s portrait in the rescued frame also can be found.

[vii] Hazard quoted in Fred Shelley, “Ebenezer Hazard’s Diary: New Jersey Dur- ing the Revolution,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society 90, no. 3 (1972): 172. Congress moved to Princeton from Philadelphia after a muti- nous group of Maryland soldiers, who feared being discharged without back pay following the cessation of hostilities, surrounded the legislators in the Pennsylvania State House for three tense hours on June 20. For the trustees’ commission of the Washington portrait, see Trustees Minutes, vol. 1, p. 236 (September 25, 1783). Peale quoted in Donald Drew Egbert, “The Nassau Hall Portrait of George Washington Reproduced in Color,” Princeton UniversityLibrary Chronicle 8, no. 2 (1947): 60.

[viii] Trustees Minutes, vol. 1, p. 236 (September 25, 1783).

[ix] William Parker Cutler and Julie Perkins Cutler, Life, Journals, and Correspon-dence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1888), 247. “Nassau Hall in Ruins,” New-York Daily Times, March 14, 1855. A Complete History of the Marquis de Lafayette, Major General in the Army of the United States of America, in the War of the Revolution . . . (New York: Robert Lowry, 1826), 453. For the Princeton booth at the World’s Colombian Exposition, see “Princeton at the Fair,” Princeton Press, September 2, 1893. On the evolution of Nassau Hall’s central space, and the history of the Washington portrait within it, see Karl Kusserow, “Memory and Meaning in the Faculty Room,” in Kusserow, Inner Sanctum, 47–114. Untitled press release dated June 12, 1908, located in the Princeton Portrait Collection file for the Washington portrait (PP222), Princeton University Art Museum.

[x] The 1847 cleaning and regilding is reported as complete, “at an expense of sixty five dollars,” in the Trustees Minutes, vol. 3, p. 477 (June 1847). Subsequent records are in the painting’s Princeton Portrait Collection file (PP222).

[xi] Thanks to Norman Muller, conservator, Princeton University Art Museum, for assistance with wood identification. For cross-section analysis confirming that the frame was originally oil-gilded, thanks to Behrooz Salimnejab, conservator of furniture and woodwork, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

[xii] See Robin D. Gwynn, Huguenot Heritage: The History and Contribution of the Huguenots in Britain, 2nd rev. ed. (Brighton, UK: Sussex Academic Press, 2001), esp. ch. 4, “Crafts and Trades.” Ware quoted in Jacob Simon, The Art of the Picture Frame: Artists, Patrons and the Framing of Portraits in Britain (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1996), 63.

[xiii] Laser removal of only the more recent layer of gilding might have been considered after consolidation; however, since the cleavage occurred at the interface between the gesso and original gilding layer (as a consequence of the latter’s stronger bond to the overgilding than to the original substrate), it would not have been possible to ensure an exact alignment of the original gold with the recarved surface beneath it. Of the particular function of such court frames as the Princeton example, Paul Mitchell and Lynn Roberts have written, “Court frames, commissioned by rulers and nobility, represent an essential, and long underestimated, component of the arts employed for propaganda purposes and as a status symbol, expressed through grandeur, luxury, and sculptural magnificence”; see Paul Mitchell and Lynn Roberts, A History of European Picture Frames (London: Merrell, 1996), 8. The slightly open miters of the Princeton frame—fixed in place by the iron brackets presumably added to secure the joints following their severance to accom- modate the Peale portrait—were left undisturbed, as closing them would have required resetting the brackets, an intrusion deemed unnecessary given the small width of the openings in comparison to the frame’s large size.

[xiv] Thanks to frame historian Lynn Roberts and to Jacob Simon, former chief curator, National Portrait Gallery, London, for guidance and assistance in identifying comparable frames. For information on Gerrard Howard, see National Portrait Gallery online catalogue, “British Picture Framemakers, 1630–1950,” s.v. “Gerrard Howard,” (accessed 30 June 2013).

[xv] All replacement carvings were produced by Carole Hallé of Carole Hallé Wood Carving Studio, New York.

[xvi] Sections of the top member of the frame not visible when it is installed were left untouched as documentation of its history. Malgorzata Sawicki, head, frames conservation, Art Gallery of New South Wales, lectures on her success using Plextol as a mordant for gilding (Plextol B500/Plextol D360 1:1, diluted 2:1 with a deionized water/ethanol mixture 4:1 for proper viscosity). Ms. Sawicki is owed a debt of gratitude for her work studying nontraditional gilding techniques and her generosity in sharing her findings.

_________________________________________________________________________________

PHOTOGRAPHY AND DRAWING CREDITS

Individual works of art appearing in this volume may be protected by copyright in the United States of America or elsewhere, and thus may not be reproduced in any form without the permission of the copyright owners. Every effort was made to obtain official permission to reproduce the works illustrated. In some cases, permission to reproduce was conditioned upon publication of a credit line or notice of copyright, as follows:

Cover: Bruce M. White

“Framing History in Early Princeton,” by Elizabeth Baughan and Karl Kusserow: Figures 1, 5, 11, 12, 22: Bruce M. White Figure 4: © Trustees of the British Museum

This article was first published in

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM Record, Volume 70 / 2011. I am extremely grateful to the authors, Elizabeth Baughan and Karl Kusserow, and to the editor of the Record, Janet Rauscher, for their kind permission to republish it on The Frame Blog.

Managing Editor: Jill Guthrie Associate Editor: Janet S. Rauscher Publications Assistants:Amanda Gannaway, Shira Gluck Copy Editor: Sharon Herson Designer: Bruce Campbell Typesetter: Mary Gladue Printer: Brilliant Graphics, Exton, Pennsylvania Subscriptions: 1 year $18.00; 3 years $45.00 Single issue: $18.00 Shipping and packaging rates apply for domestic and international subscriptions. Back numbers are available as supplies last from the Princeton University Art Museum and online through JSTOR, EBSCO, and Wilson Web.

© 2011 by the Trustees of Princeton University All rights reserved ISSN 0032-843 x

All submitted manuscripts are reviewed by members of the Publications Committee drawn from the staff of the Princeton University Art Museum and using the advice of outside readers.

The publication was made possible by the Mildred Clarke Pressinger von Kienbusch Memorial Fund and the Friends of the Princeton University Art Museum.

More on American frames here:

Framing George Bellows: Ashcan artist > here

Conserving a Stanford White frame> here

This is a great article; thank you for posting it. I especially appreciate the detail the author gets into regarding the restoration process. Also, the accompanying pictures help a great deal in understanding restoration techniques as well as appreciating the skill required to perform such a task. In today’s post-industrial revolution world of machine-made molding, it is interesting to read about a frame that is a true work of art. And one with a fascinating history to boot.

Thank you again for posting this.

LikeLike

Thank you, Peter, for such an appreciative comment, & for taking the time to post it. I was lucky to get permission to republish this article – it’s such a good story, and that, combined with an expert description of the conservation process, makes the whole project particularly interesting. It would be nice to think that a lot of such stories were in progress round the world, but even this one took some years to get going, because of the necessity of raising sufficient funds. Perhaps this is the point where museums should stop thinking of acquiring more and more stuff, and use their resources on this sort of project, which combines research with restoration and the best possible display of the objects already in their collections…

LikeLike