National Gallery frames: an interview with Peter Schade

by The Frame Blog

Peter Schade, Head of the Framing Department, has worked in the National Gallery, London, since 2005. He is responsible for the frames of the more than two thousand paintings which make up the UK’s major collection of European art.

The Frame Blog: What exactly does your work at the National Gallery entail?

Peter Schade: I spend most of my time trying to find appropriate old frames that are contemporary for the Gallery’s pictures.

FB: How were you trained, and what brought you into picture frames as a speciality?

PS: I became a woodcarver by accident. Under normal circumstances I would have done my Abitur (the German equivalent of ‘A’ Levels) and gone to University, but I was born in East Germany and at that time education was very tightly controlled, and so it was not possible for me. Instead I applied for an apprenticeship – specifically for one of the two woodcarving places which were offered, because carving appealed to my creative side. I moved to London in 1990, and that’s when I first worked with picture frames. I became a carver at Arnold Wiggins & Sons, which then had a very large workshop. After a few years I opened my own workshop, which I still maintain.

FB: In an institution like the National Gallery, you are dealing with many eras and nationalities of art. Does this make continual demands on you, to research new areas? – for example, provincial styles in Italy or France? How do you go about finding out what you need to know, when a work originates from an especially exotic or obscure region?

PS: Because we try to use old frames for the pictures, we are limited in our choice by their availability, so we’re generally happy to find something from the country of origin and roughly the same period. This should result in time in whole areas of the gallery being framed in patterns that relate harmoniously not only to the pictures but also to one another. We are not aiming to recreate entirely the original setting for each painting which, if at all, would only really be possible by using many reproduction frames. The problem with reproduction frames is that they date very quickly – they always, in the end, reveal the time they were made, rather than the intended historically accurate appearance. We have over a hundred & fifty years’ worth of copied styles to look back upon here at the National Gallery, and this has helped to change our framing policy. Before I came to the Gallery, money for buying old frames had to be applied for from emergency funds, most frame changes were into replicas of original frames, and there wasn’t the emphasis there is now on original frames. I always try to find an antique frame that’s contemporary with the picture; I would only consider making a copy if there’s a time constraint, such as a forthcoming exhibition, or there’s very little possibility of acquiring an antique frame of the right size and period.

Working on the frame for Veronese, The Adoration of the Kings, 1573, 140 x 126 in. (355.6 x 320 cm), National Gallery, NG268

FB: Picture frames have at last become a respectable area of art historical study over the last 20 years. Has it made a great difference to the way in which you work, now that curators are much more alive to the importance of the frame on a painting?

PS: A few curators have an interest in and knowledge of picture frames – and of course Nicholas Penny [director of the National Gallery since 2008] has a long-standing interest in the subject – but I have not observed a general trend towards a greater understanding or a deeper curatorial interest in the framing of pictures. There has only been marginal academic interest in framing and the field is difficult to comprehend through library research alone. Provenance and other historical data are mostly lost for individual frames and judgements of taste and quality have to be made.

FB: How much consultation occurs between your department and the relevant curators when it comes to reframing a work of art?

PS: Reframings are suggested by the Framing Department and always have to be approved by the curator of the department the painting in question belongs to.

FB: How much involvement do you have with the temporary exhibitions mounted by the National Gallery? For instance, where the frame of a painting is too fragile to travel, is the choice of an exhibition frame left up to you?

PS: Occasionally paintings come without frames and have to be framed for an exhibition, in which case I suggest a solution, depending on timing and budget. There, of course, we may construct a replica of an existing frame, or a copy of an antique pattern of the right period.

FB: Are there works in the National Gallery which can’t be reframed for any reason? Because they have been left or given to the Gallery as an integral work of art? or could you, in theory, reframe any of the paintings if the result were an improvement?

Pisanello, The Virgin and Child with Saints Anthony Abbot and George, c.1435-41, National Gallery, NG776

PS: Some paintings are in their original frames and would not be reframed. Some later frames are of greater historical interest such as the frame for Pisanello’s The Virgin and Child with Saints Anthony Abbot and George, which was designed by Sir Charles Eastlake for the painting [1]. I don’t think that the frame is suitable for the painting, but it will probably not be changed; it is mounted with 19th century imitations of medals by Pisanello.

FB: What do you think about collectors’ frames? For instance, the National Gallery owns Poussin’s The Adoration of the Golden Calf, which, with its pendant, The Crossing of the Red Sea (now in the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne), was framed alike in 1710 by Jean-Baptiste le Ragois de Bretonvilliers for his Parisian hôtel. These frames are far more elaborate and much later in style than would originally have been used for Poussin’s work; how far should we go to protect the mutual history of painting and frame, at the expense of historical accuracy?

Nicolas Poussin, The Adoration of the Golden Calf, 1633-34, National Gallery, NG5597

Nicolas Poussin, The Adoration of the Golden Calf, 1633-34, National Gallery, NG5597

PS: We have at least three frames that were made for the pictures while they were part of French collections in the eighteenth century: Poussin’s The Adoration of the Golden Calf, Rembrandt’s Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels [& see NG Review 2008-2009, p. 30], and Elsheimer’s The Baptism of Christ. Of these the frame for the Golden Calf is of the highest quality – probably, in terms of specialized craftsmanship, it’s the best frame that we have in the entire gallery. Surprisingly few frames have such a clear link to earlier collections through their frames. When these frames are of good quality and not distracting for the painting or the display we would not aim to change them.

FB: Are there many examples of frames which have been taken off their paintings, but having languished for some time in storage, have been restored to their original pictures? Like the frame of Ingres’s Madame Moitessier, for instance, which was thought to be too elaborate for the portrait? There are fashions in taste, with frames, as with everything else…

Jan van Eyck Portrait of Giovanni (?) Arnolfini and his Wife, 1434, National Gallery, NG186

PS: All the frames that are removed from their paintings are now kept and could be put back. For example, Jan van Eyck’s Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife is back in its 19th century Neo-Gothic frame[2], and Van Dyck’s Charity (c.1627-28) was put back into an elaborate English 19th century collector’s frame in 2005. This kind of reappraisal is rare.

FB: Is there a work in the Gallery which you feel most satisfied with, as a result of finding the right frame for it?

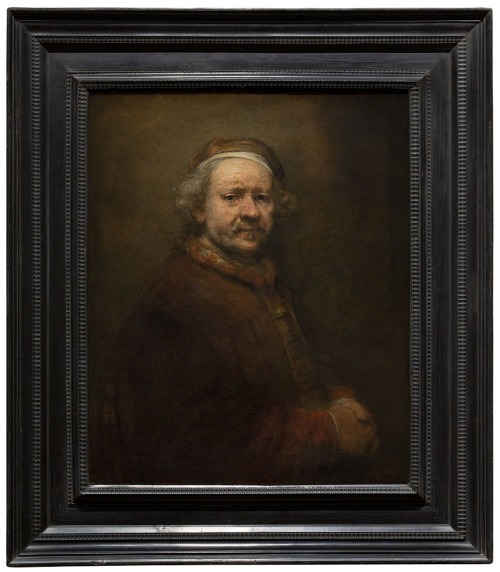

Rembrandt, Self Portrait at the Age of 63, 1669, National Gallery, NG21 1

PS: We have found a few frames, which I would regard as ideal and permanent frames, for instance: Rembrandt, Self Portrait at the Age of 63; Lotto, The Physician Giovanni Agostino della Torre and his son Niccolò; and Giordano, Perseus turning Phineas and his Followers to Stone (see below for illustrations). It is particularly pleasing when frames can be found that are of exactly the right size (such as the Lotto and the Rembrandt). We have managed to do this about 25 times over the last eight years. The real test is, of course, how these frames will look in 50 or 100 years time.

FB: Where do you find the antique frames you need?

Poussin, The nurture of Bacchus, c.1628, National Gallery, NG39

PS: London frame dealers are a good starting point, but over the years we have bought frames from about twenty different sources. These include, as well as the frame dealers, general antique dealers, auction houses and private individuals. The dealers tend to be the most expensive option, but they also have the greatest choice. An example is the 17th century antique French frame which we acquired from a London dealer for Poussin’s The nurture of Bacchus. This had previously been framed in a 20th century replica of an 18th century French frame, so it was unsatisfactory from several points of view. As soon as we (I, and the curator of 17th & 18th century French paintings) saw the antique frame, we knew that we had to have it; it was the perfect solution to displaying such an important painting. It would have used up a sizeable percentage of my purchasing budget, but fortunately a generous private donor contributed to the cost.

Raphael, The Madonna of the pinks (‘La Madonna dei Garofani’), c. 1506-07, National Gallery, NG6596

On the other hand, I have discovered frames myself: the early 16th century Venetian frame on Raphael’s Madonna of the pinks came from a source I found while on holiday in Munich – it was almost exactly the right size, and a very reasonable price.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin of the Rocks, c.1491/2-99 & 1506-08, National Gallery, NG1093

Another option can be for the workshop to construct a frame around separate antique elements which come onto the market. A recent example of this is Leonardo’s The Virgin of the Rocks, which underwent treatment a few years ago by our chief conservator, Larry Keith [3]. At the same time, three sides of an original 16th century altarpiece frame came up at an antiques auction in Genoa – two pilasters and the cornice.

They were typical of a Northern Italian aedicular frame of 1480-1510, and I could see that they were exactly the right size for The Virgin of the Rocks, which had previously been framed in the 19th century idea of a 16th century frame.

Giacomo del Maino & workshop, Altar of the Immaculate Conception, post-1495, S. Maurizio, Ponte in Valtellina

Larry travelled to Ponte in Valtellina, Lombardy, where there is a surviving frame (on the Altar of the Immaculate Conception) made by the workshop of Giacomo del Maino, from whom the original frame had been commissioned for The Virgin of the Rocks. It has elements very similar to the three sides of the frame which we had bought at auction, and we based parts of the reconstruction on that existing large frame.

FB: Do you have any pet wishes for reframing? A painting which you would like most of all to see in a suitable frame?

PS: The most complicated issue for us is finding big enough frames, as many of the collection’s paintings are large. Most of the Gallery’s paintings could be better framed – the large Belshazzar’s Feast by Rembrandt, for instance. The Rembrandt is 66 x 82 3/8 in. or 167.6 x 209.2 cm., which is a very large painting, and Netherlandish frames of this size are rare, so in this case – because we have no other option – we will eventually make a frame for it. Ebony frames can actually be copied reasonably well, since ebony doesn’t acquire a patina of age, like a gilded frame. When I started working in the National Gallery, there wasn’t an original ebony frame in the collection, which illustrates the lack of interest invested in the display of paintings through much of the western world during the 20th century.

Vincent van Gogh, Fifteen sunflowers, 1888, National Gallery, NG3863

FB: Is there a period or nationality of work which is more difficult to frame well, because of a lack of historical evidence, or because (like Van Gogh’s Sunflowers) the artist’s own frame would look out of keeping to modern eyes?

PS: Over the last eight years we have reframed pictures in almost every part of the Gallery. To my eye all of them are improvements on what we had before, but we will have to wait and see how successful they are in the long term. Recreating frames that were designed and made by artists is to my mind not possible or desirable.

FB: The Gallery must have a large archive of photos of framed paintings. How do you build up a reference library of this sort, so different from the usual art historical library?

PS: Photographs of current and former frames are stored in the Framing Department’s physical dossiers. Nicolas Penny conducted a frame survey with the late Paul Levi in the 1990s, which examined every frame in our collection, and this research forms the backbone of our frame archive. We also archive digital images of frames taken in more recent years by the Gallery’s Photographic Department.

FB: How big a team of people do you have working in the department?

PS: I am the Head of the Framing Department, which also employs a frame conservator and frame technician, plus a part-time administrator. Many of our more ambitious projects are undertaken in collaboration with freelance specialists. We are lucky that London has become the world centre for recreating and restoring old frames, and as a result a number of very experienced specialists are based here.

Working on the frame for Leonardo, The Virgin of the Rocks

FB: Do you, yourself, often create a whole frame from scratch? – designing, carving and gilding the whole object? Is there any aspect of making a frame that you particularly prefer?

PS: I am more confident at all aspects of woodwork and would generally work with specialised gilders and finishers for the finished surface, but I have also painted, gilded and toned frames that are on display in the gallery. I like to revisit the frames that I’ve worked on, seeing which are more successful than others after they’ve settled in. But just being able to look back on what has been done in such a remarkable collection gives me great pleasure.

Lotto, The Physician Giovanni Agostino della Torre and his son Niccolò, c.1513-16, National Gallery, NG699

FB: What do you feel about giving a newly-made frame a patina of age? Should gilding be left to age naturally, or should it be toned to look contemporary with the painting? Different countries have different approaches to this vexed question; what are your own views?

PS: In my view, for the frame to function properly it has to complement the age of the painting. I am familiar with the different approaches to ageing the surface of a new frame, and in the end the finished surface is a judgement of taste. I aim to create a believable link between painting and frame; this cannot happen if the frame is obviously new. When painting and frame appear as a single object, the painting can be more readily experienced as a three-dimensional thing, the original work of art rather than an image that could be looked at in a book or on a screen.

FB: Do you think that the frame should be chosen solely in response to the work of art it is for, or should there be some consideration of the room where it is to hang, and the other frames which will surround it?

Luca Giordano, Perseus turning Phineas and his Followers to Stone, early 1680s, National Gallery, NG6487

PS: The frame should harmonize with the painting and intensify the illusion of space. It is important that it looks right in the room; frames are sometimes rejected because they would set the wrong accent by being too imposing (or not important enough), relative to the status of the particular painting within the Collection. The hang of the pictures in almost all the Gallery rooms changes very frequently and it is not possible to anticipate exactly which paintings would hang next to one another for any length of time.

FB: Do you have a favourite style of frame?

PS: I don’t have a favourite style of frame, I enjoy the enormous variety of frame designs that have evolved in five hundred years of European framemaking.

FB: What would you like to do next?

PS: Trying to improve the Gallery’s frames is a huge undertaking and can only be done very gradually; what we have done so far is only a beginning. I hope that with curatorial goodwill and financial backing we will be able to continue with what we have started.

FB: Thank you for an extremely interesting and informative interview, and good luck with your next project!

….UPDATE….

Bronzino, Madonna and Child with saints, c. 1540, National Gallery, NG5280

This is the most recent reframing at the National Gallery: a magnificent unaltered Tuscan Mannerist frame of exactly the right size for Bronzino’s Madonna and Child. The parcel-gilt finish and dramatically fluted scotia complement the dynamism of the composition and set off the jewelled colours and opalescent flesh; the strong inward thrust of the fluting also enhances the spatial depth of what might otherwise be a rather shallow pictorial structure. Bronzino, like Pontormo, is an artist whose work really repays framing in these historically accurate but very powerful Mannerist designs; compare Pontormo’s Halberdier (Getty Center).

****************************************************************

With thanks to Peter Schade for his time, and to Hazel Aitken and Darragh Kenny of the National Gallery for their help with the images used in this article.

National Gallery reframings: Mannerist frames > here

National Gallery reframings: a Venetian pastiglia frame> here

National Gallery: reframing Mantegna> here

Reframing the Renaissance: Museums and Madonnas> here

National Gallery exhibition: Sansovino frames> here

[1] Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (1793-1865) was the first Director of the National Gallery (from 1855), having been Keeper of the Gallery from 1843-48. He was also a painter, and acted as buyer for the Gallery; he wished to display his acquisitions in suitable frames, and in galleries which were appropriately decorated and chronologically arranged. Brian Sewell notes of this particular frame, ‘the Neo-Gothic absurdity containing the Pisanello, he commissioned in Milan, possibly to his own design’.

[2] This is the frame which Holman Hunt recorded seeing on the Arnolfini Marriage Portrait in the 1840s, although when he was writing his book on the Pre-Raphaelites 60 years later, he remembered it as a ‘dignified ebony frame’. See William Holman Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 1905, vol. I, p.54.

[3] See the article on the conservation and reframing of The Virgin of the Rocks in the National Gallery Technical Bulletin, vol. XXXII; downloadable pdf here; see also Michelle O’Malley, The business of art, 2005, Yale University Press, p.83. Further notes on reframing works in the Collection can be found in the National Gallery Reviews (online), for April 2007-March 2008 (p. 24 ff); April 2008-March 2009 (p. 28 ff); April 2010-March 2011 (p. 20 ff); and April 2012-March 2013 (p. 40 ff).

[…] Head of Framing at the National Gallery, London […]

LikeLike

[…] of short articles on the reframing projects undertaken by the National Gallery, London, under the Head of Framing, Peter Schade. The articles were originally published in the National Gallery’s Review of the Year, from […]

LikeLike

[…] short articles on the reframing projects undertaken by the National Gallery, London, under the Head of Framing, Peter Schade. The articles were originally published in the National Gallery’s Review of the Year, from […]

LikeLike

[…] of short articles on the reframing projects undertaken by the National Gallery, London, under the Head of Framing, Peter Schade. The articles were originally published in the National Gallery’s Review of the Year, from […]

LikeLike

What a fascinating interview and opened up a whole new area of interest for me. I had noticed the new Rembrandt frame and loved it – I will pay a lot more attention to frames on my future gallery visits – funny how the ones that don’t work (for me)are the ones I notice usually

LikeLike

I’m glad that you enjoyed the interview. Frames are so important to the presentation of paintings – we may not notice, until attention is drawn to them, what is making pictures appear at their best, and as they might originally have been seen, or what may be impeding our view of them…

LikeLike

Thanks – fascinating, and all good news for the NG. My only disagreement is about choosing frames appropriate to the importance of the work. I think it’s fine to frame an important picture in a modest frame – greatness has its own presence. I really dislike the grandiloquent frames on the Louvre’s Vermeers, for example, which try too hard to draw attention to small but important pictures. I also think it’s fine to frame a more modestly important picture in a grand frame, if the frame is otherwise appropriate for the picture.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for commenting – and I do see that what Peter said could be read in that way. I think, however, that he was probably referring to the proportions and quality of the frame, relative to the painting, as well as to the refinement of any carving. The Rembrandt Self-portrait at the Age of 63, for instance, has been moved from a French pattern to the relative sobriety of an ebony ripple frame, which is a diminution of grandiloquence, but an accession of quality and aesthetic value. The Giordano Perseus was in a much plainer but very heavy moulding before the one in the article. Overburdening the work of Vermeer with inappropriately ornamental frames is the last thing he would do; in fact, I think that’s what he means by being too imposing. Perhaps I should have edited what he said slightly, to convey this better…

LikeLike

Well that’s a relief! Everything else sounded so good. It is a particular pet hate of mine. A lot of galleries go for daft elaborate frames around tiny pictures. Raphael suffers too – especially the little one in the Hermitage. Excellent interview, anyway – thanks!

LikeLike

Strange that you should mention the Raphael in the Hermitage – I’ve been looking into it (as it’s so bizarre), and there seems to be an internet idea, for some reason, that it’s in an original frame, probably ‘designed by Raphael himself’! I think it’s much more likely that the frame is a Venetian restello. The fact that it’s since been entombed in a sort of Las Vegas summerhouse doesn’t help the poor little thing…

LikeLike

Really excellent interview. Thank you

Robert

LikeLike

Thank you, Robert – I do appreciate your taking the time to comment: very nice of you.

Best wishes,

Lynn

LikeLike

Thank you – how nice of you!

LikeLike

Thank you; how nice of you!

LikeLike

Lynne, That post was just great. Of course, Peter is wonderful, but the structure of your interview was equally good. You asked all the right questions that shaped a really informative interview. Excellent work!

How do you find the time?

I promise you something soon,

All the best,

George

LikeLike

Thank you, George – how kind of you! Interviews are particularly interesting, as they give a chance to get under the skin of a big institution – although sometimes you can’t get quite as far as you’d like, because of the delicate political balances…

I would really love you to write a piece for me, if you can fit it in, please –

V. best wishes,

Lynn

LikeLike