Serge Roche: Cadres français et étrangers du XVe siècle au XVIIIe siècle – Part 1

by The Frame Blog

Serge Roche (1898-1988) was a Parisian designer, specializing in furniture, lighting, looking-glasses and conversation pieces, whose work became extremely fashionable from the 1930s onward. He is better-known, perhaps, amongst those interested in picture frames, for his great folio of sharply-photographed historic frames, published as Cadres français et étrangers du XVe au XVIIIe siècle: Allemagne, Angleterre, Espagne, France, Italie, Pays-Bas, to accompany his exhibition, L’exposition internationale du cadre du XVe au XXe siècle, at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1931. This article, written in collaboration with Andrew Levi, looks at part of the collection of frames assembled in Cadres français et étrangers…

Odilon Roche (1866-1947), ‘Dancer’: Isadora Duncan, 1943, 28 x 38 cm., pencil & watercolour (modern frame), Galleria Pirra, Turin

Serge Roche was the second son of Odilon Roche, watercolourist, artists’ supplier, and dealer in antiques and antiquities, whose shop in the rue Victor Massé had originally sold materials to some of the most notable painters in Montmartre [1]. Roche’s father expanded into old frames, and then into antique French furniture, antiquities and Chinese lacquerware; but in spite of such an aesthetic inheritance, Roche himself apparently intended to become an engineer. This ambition was derailed by an embryonic architect friend, under whose influence he embarked on a modern European Grand Tour which ended in Italy, and his falling in love with the Baroque. Back in Paris he arranged an exhibition of antique French frames in his own apartment, selling ‘around 100 of them in two weeks’. This was followed in 1931 by the larger, in all senses, Exposition internationale du cadre du XVe au XXe siècle at the Georges Petit gallery.

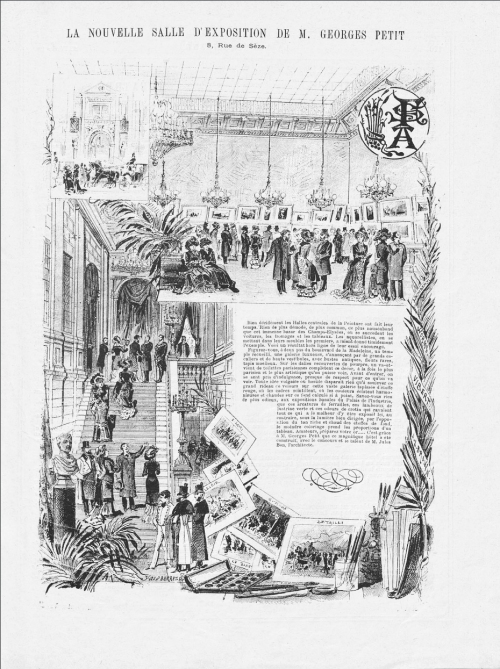

‘M. Georges Petit’s new exhibition hall’, from La vie parisienne, 25 February 1882

Even today an exhibition of frames is unusual: a striking event, worthy of comment; but in the 1930s it was similar to the exhibition of a flock of live dodos in the French art world. This was the period when artists were sloughing off the frame as old-fashioned, restrictive, the outmoded ornamental distraction of a previous century; nothing to do with the minimalist, streamlined geometry of the Jazz Age. In this atmosphere, exhibiting empty antique frames without their paintings was the most extraordinary gesture; and then to make it in a gallery which had been for around eighty years in the forefront of the French art world…!

Georges Petit, inheriting his father’s gallery near the Opéra in Paris in 1877, had begun to exhibit the work of the Impressionists, including, for example, a double retrospective focused on Monet and Rodin. Shortly before the latter, he had refurbished the gallery, creating an entrance and exhibition room similar in style to those of the Grosvenor Gallery in London, with a processional staircase, plants, drapery and statues, and an exhibition hall roofed by an immense full-size skylight, where the exhibits were well-spaced and lit. By the time that Roche came to fill the latter in 1931, Petit himself had been dead for eleven years, and his gallery had been taken over by the Bernheim-Jeune brothers, equally prominent in the world of avant-garde art. In the same year as the frame exhibition, a Matisse retrospective took place there, to be followed the next year by one on Picasso; in 1933, however, the gallery closed. No further important exhibitions of picture frames would take place until the 1980s, more than fifty years after Roche’s.

Serge Roche (right) greeting André Malraux at the Grand Palais in 1960 (Archives Serge Roche); frame from Plate 26 of Cadres français et etrangers…

It seems to be from the time of this exhibition or immediately after that Roche’s own designs began to take off. He produced drawings for furniture, interiors, and – especially – looking-glasses, in which the skeletons of 17th and 18th century Baroque frames, tables, sconces, were clad in the glazed and mirrored plating of Art Deco.

Serge Roche (1898-1988), looking-glass, c.1934, opaline & mirrored glass & beechwood, 37 x 32 5/8 ins (94 x 83 cm.), stamped ‘Serge Roche, Décorateur, 125, Boul. Haussmann, Balzac 23-28’, Christie’s, New York, 12 June 2014, Lot 95; and Plate 14 of Cadres français et etrangers…

For example, this 17th century Louis XIV frame, with its gentle ogee profile and calligraphic foliate C-scrolls carved in shallow relief and gilded, may look light years away from the mirrored glass frame of the looking-glass behind it, but the latter has a very similar structure, with rectilinear contours, corner areas and rail differentiated by carefully-placed jointed strips of glass, an inner frieze, and corner-&-centre ornaments straying onto the inner and outer mouldings.

Serge Roche (designer; 1898-1988), Mariano Andreu (artist; 1888-1976), looking-glass, c.1935, wood, glass, painted metal & paper, 50 x 42 ¼ ins (127 x 107.3 cm.), Christie’s, New York, 18 December 2015, Lot 349; montaged with Plate 30 of Cadres français et etrangers…

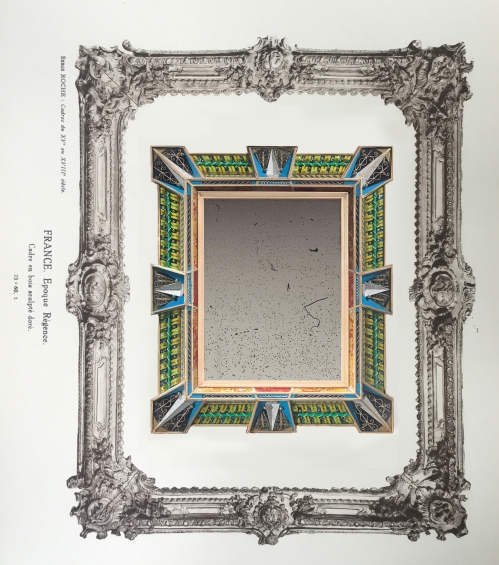

Likewise with this early 18th century Régence frame, its projecting corners arrowing outwards, and its parallel orders of decoration based around raked fluting and a twisted ribbon: dissect its ornament and simplify its curving forms to stylized geometric rhomboids and wedges, and this 1930s looking-glass frame emerges, to be coloured in bright acidic paints instead of soft gold.

The frame exhibition itself, however, seems not to have foreshadowed any of this contemporary remaking of its contents. It – or, at least, the folio of accompanying images – was a straightforwardly historical panorama, which began with some of the most famous surviving early altarpieces in France – the towering mediaeval castle-like constructions made for the Confrérie du Puy Notre-Dame d’Amiens, now removed from the cathedral of Amiens to the Musée de Picardie.

Aimé (1803-69) or Louis (1807-74) Duthoit, Interior of the Cathedrale d’Amiens (showing some of the ‘Puy’ altarpieces), watercolour, Musée de Picardie

The Confrérie was a society of the wealthier inhabitants of Amiens, founded in 1389 and dedicated to the Virgin Mary, which celebrated her each year in a sort of arts festival, combining the recitation of poetry made in her honour with the creation of a specially commissioned altarpiece, also based on a poem or sacred maxim. These seem to have been produced once a year from the 15th century until 1666, eventually numbering as many as 185; although in 1723 they were mostly removed from the cathedral and all but twenty or so were lost [2].

Altarpieces for the Confrérie du Puy Notre-Dame d’Amiens: Pour nostre foy militante comtesse, 1525; Pré ministrant pasture salutaire, 1519, Musée de Picardie; and Plate 1 of Cadres français et etrangers… : ‘1519; Cadres en bois sculpté; Exécutés pour la Confrérie du Puys Notre-Dame d’Amiens. 173 x 97, t.’

Altarpiece of Confrérie du Puy Notre-Dame d’Amiens: Au juste pois véritable balance, 1518, commissioned by Antoine Piquet, procureur for the king, Musée de Picardie; & Plate 2 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘1518; Cadre en bois sculpté; Exécuté pour la Confrérie du Puys Notre-Dame d’Amiens’

It is not clear whether Roche actually borrowed some of these altarpieces for his exhibition (which seems rather unlikely), or whether they were merely photographed for the book, to complete the chronological arc he was aiming for. The photographs are excellent – clear and detailed, taken in such a light and at such an angle as to be most revealing: neither of which would be easily available in the museum without a great deal of preparation. They have all had the paintings excised from them, presumably to allow a complete focus on the carved details of figures, angels, cherub heads, heads in relief, arches, niches and finials; but even seeing them as displayed in Amiens today, frame and painting still making one complete whole, they are far from what their original appearance would have been. The museum caption to the single altarpiece, above, Au juste poids véritable balance, notes that the original frame is made of oak, and was at one point ‘painted and gilded, [with] rare traces of polychromy’. The images that this conjures, spectrally brilliant with masses and details of gold and colour, are paradoxical echoes of the painted frames Roche designed to be realized by Mariano Andreù.

The frames themselves are as anonymous as the five earliest paintings (1518-25) surviving in Amiens; the artist of this group is labelled only as ‘Maître d’Amiens’, and no sculptor seems to have been recorded for the cathedrals of wood which so miraculously present them in analogues of the Celestial Church [3]. The tallest of them is 383 cms high; the winning poems to the Virgin, inscribed on parchment, were apparently also displayed in miniature frames which must have reflected the gigantic Gothic frames of the altarpieces.

Plate 3 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Cadres en bois sculpté doré; I. Première moitié du XVIIe siècle, 81 x 65, t[otale]….[4]’; and on Titian (fl. c.1506-d.1576), Gerolamo (?) Barbarigo, c.1510, o/c, 81.2 x 66.3 cm., National Gallery, London

Many of the post-Gothic frames in Roche’s folio collection had been sold in London after the French Revolution, and were dispersed to various collections, sometimes to surface again in museums. An example of this is the late French Renaissance reverse profile frame (first half of the 17th century) shown in Plate 3 of the book; it now contains Titian’s portrait of a member of the Barbarigo family. This stunning confection is carved in high relief with two branches of a grapevine, bound at the centre of the bottom rail and meeting at the top; the leaves and stalks are undercut, and incised with veins and texturing on the branches; the torus at the sight edge has an enriched floral guilloche chain. It was most probably created for a painting of Christ or of a Madonna and Child, the grapevine symbolizing the Eucharist; however, it might also have been intended for a secular mythology of Dionysos. It is one of the most beautiful frames in the Gallery, and – although it has no symbolic, national or chronological connection with Titian’s portrait – it creates an ornamental halo for the latter which presents it to the spectator with added power and theatricality, enhancing the mysterious authority in the sitter’s gaze.

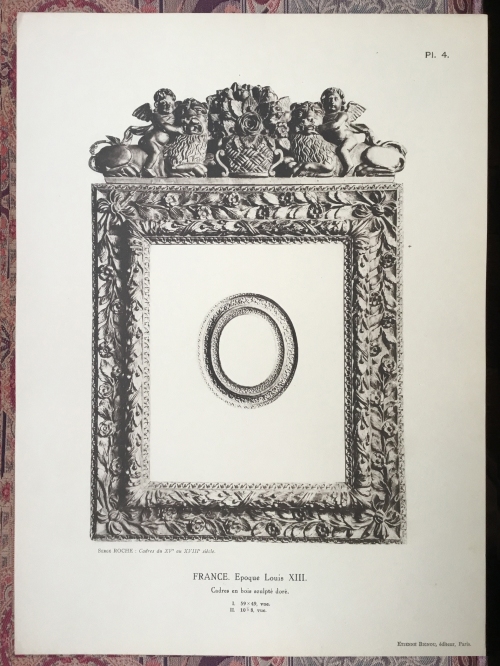

Plate 4 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIII: Cadres en bois sculpté doré; I. 59 x 49, vue; II. 10 x 8, vue’

The Louis XIII reverse fronton frame shown in Plate 4 is another instance of ambivalent meaning: with angels riding lions (a symbol of the compassion of Christ) in the fronton, and roses in the basket they support, as well as branches of roses (an attribute of the Virgin) along the rails, this might have been made for a Madonna and Child; it might equally have displayed the portrait of a noblewoman, or even a queen. The very sharp resolution of the black-&-white image reveals the profile with admiral clarity, as well as details of the bound imbricated bay leaf torus at the sight edge, and the roses on the frieze.

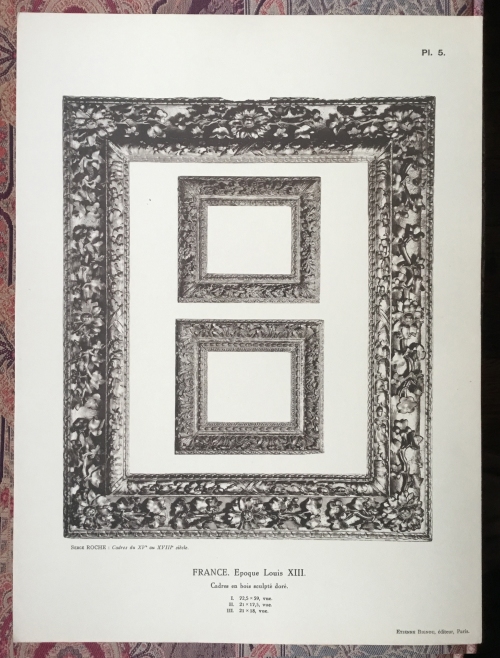

Plate 5 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIII: Cadres en bois sculpté doré; I. 72.5 x 59, vue; II. 21 x 17.5, vue; III. 21 x 18, vue’

Plates 5 and 6 show two more Louis XIII reverse frames; the outer frame in Plate 5 (the photo possibly printed upside-down) has a garland of oak leaves and acorns on the torus at the sight edge, and a frieze with sunflowers at the corners and centres, carved, like their foliage and some small florets, in high relief. This may be another frame with a sacred meaning – the sunflower turning towards the sun/Christ, and the oak leaves standing for faith – or the sunflower might also have been chosen as the flower of Apollo, god of music and the arts, with the oak leaves indicating strength and endurance. The execution, like that of the two previous frames, is particularly fine and clear, the treatment of the three-dimensional flowers and foliage managing to be both naturalistic and supremely decorative.

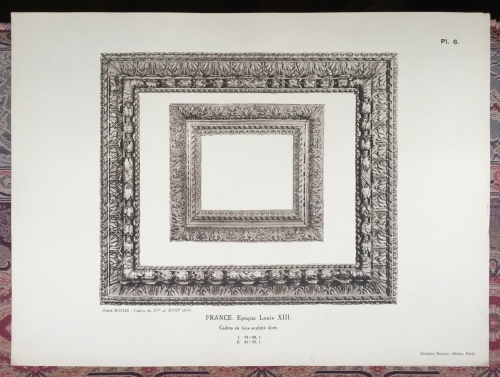

Plate 6 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIII: Cadres en bois sculpté doré; I. 73 x 60, t; II. 41 x 33, t.’

The outer frame in Plate 6 has no symbolic meaning but is purely ornamental. It is embellished with five orders of decoration including a frieze of cross-cut acanthus leaves, and a centred and bound torus with a garland of bunched bay leaves. Its effect can be judged from the very similar profiles of the previous Louis XIII frames; typically Baroque, the raised, leafy torus at the sight edge is designed to push the painting forward, highlighting it with the bunches of bay leaves which are tied and hung on the ribbon crossing them at the centres. At the same time the parallel thrust of the bay leaf torus and spiral ribbon creates a tension with the perpendicular emphasis of the acanthus leaves, and adds to the light-catching property of so much rich ornament: this is a frame which is full of animation and movement. The smaller frame on this page uses some of the same ornaments, but with a convex (bird’s-beak) moulding.

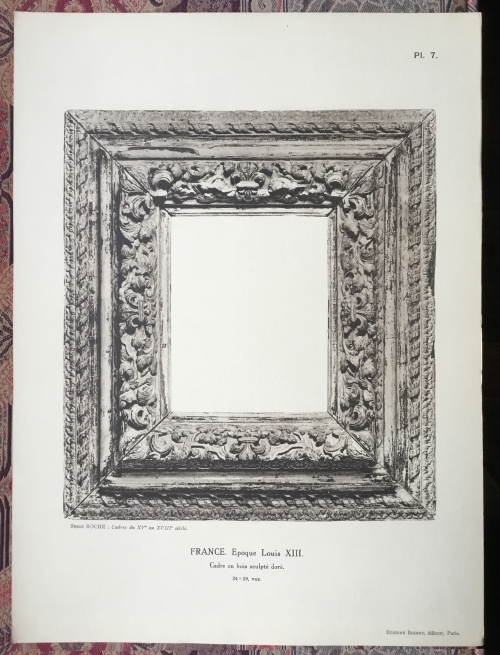

Plate 7 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIII: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 24 x 19, vue’

Another variation on a Louis XIII reverse profile, with foliate strapwork on the sight moulding, and with fleur-de-lys at the corners and centres – possibly therefore having with royal connotations.

Plate 8 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIII: Cadres en bois sculpté doré; I. 78 x 59.5, vue; II. 79 x 64, vue’

Two more Louis XIII reverse frames: the upper, wider frame has a slightly concave frieze, carved with scallop shells and lilies trailing tendrils of husks; the torus at the sight edge has a boldly raked decoration of crinkled bay leaves and husks. Like the frames in Plates 3, 4 and 5, this is likely to have been a particular commission for a particular painting, client or interior; Roche seems to have had a talent for assembling these idiosyncratically beautiful objects. Again, this may originally have housed a sacred image; it seems to have been printed sideways, and is probably a portrait format, possibly for a Madonna and Child (the lilies, for purity) and John the Baptist (the scallop shells, symbolizing baptism).

The lower frame is purely decorative, with intricately-carved alternating acanthus and sprays of florets on the back edge, and an enriched floral chain on the torus.

Plate 9 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIII: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 73 x 60, t.’; and montaged with Titian (fl. c.1506-d.1576; previously attrib. to Giorgione), Head of a man, c.1508-10, 47 x 40.5 cm., Kelvingrove, Glasgow

Plate 9 shows another very richly carved Louis XIII frame, with scallop shells along the back edge, an intricately carved shallow torus with foliage, scrolls and florets, a ribbon-&-stave and acanthus tip sight edge. According to an MS note by Paul Levi [5], who completed a survey of the frames in the National Gallery, London, in the 1990s, this frame is in storage in the Gallery, and is

‘reputed to have been the frame for a Giorgione fragment head of a man (in Glasgow part of their large Giorgione’.

This refers to the fragment above, now attributed to Titian, and originally part of Christ and the adulteress (the bent knee belonging to the owner of the head can be seen, jutting into the rest of the canvas at the lower right edge, over the white skirt of the woman). The note also records the fact that the frame was labelled as Italian in the National Gallery – presumably because the scallop shells in combination with a Giorgione/ Titian link pointed towards a Venetian origin. However, these shells might also mean that it was originally made to frame either a head of John the Baptist, or a figure of Aphrodite.

Plate 10 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Milieu XVIIe siècle: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 71.5 x 58.5, vue’; and detail

The frame in Plate 10 shows the collection moving from the period when the Baroque was expressed through the chiaroscuro generated by tiers of opposed convex and concave mouldings, towards a dramatic contour of thrusting corner ornaments, which can focus attention on the diagonal lines of a painted composition. This is a striking panel frame, in which the shaped, mirrored reposes in burnished gold are contrasted with the matte, textured ground of the carved corners. This early Louis XIV profile has softened from a convex or torus form into an ogee, and the foliate strapwork in the corners is – as well as a focal island – also perhaps an economy of carving the whole rail, in a foretaste of Bérainesque ornament. Fanned lambrequins jut, like tiny shells, from the ends of the mitres, and across the angles are miniature carved trophies in the form of Cupid’s quiver crossed by the flaming torch of love. This could, therefore, have been the frame made for a betrothal or marriage portrait; perhaps even one of a pair belonging to the portraits of husband and wife.

Plate 11 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 144 x 130, vue’

This corner of a Louis XIV frame in full flow of scrolling foliate strapwork, with beautifully recut veined acanthus leaves, cross-hatched ground, minute rinceaux, and a sight edge of opposed C-scrolls and leaf buds on a hatched ground, is published in microscopically clear close-up to demonstrate the skill and organization of design, detail, and execution. It is around 5 ½ feet high – a master’s sculpture in wood which can be examined closely and appreciated in its smallest curlicue, but, stepped away from so that the painting may be seen, will dissolve into a shimmering pergola twined with spiralling leaves and buds and tendrils, catching flickers of light which can animate any portrait or landscape.

Plate 12 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 26 x 24, vue; Style Jean Bérain (1674-1711)’

The Louis XV frame of Plate 12, showing the symbols of Christ’s Passion at top and base, with the Eucharistic grapes and wheat at the sides; private collection

The outer frame in Plate 12 is interesting not only for its simple architrave structure, its frieze decorated with a strapwork fret, but for the small religious trophies set in the openings of the fret. The lateral sides are centred on bunches of grapes, with ears of wheat at each end, whilst the top is centred on Longinus’s spear (with which he pierced Christ’s side) and the sponge soaked in vinegar on a stick; the bottom rail has the ladder to climb the Cross, a flaming torch and what may be intended for a nail. This is thus a frame marked with symbols of the Eucharist and of Christ’s Passion, and which may have held a scene of the Crucifixion, an Ecce Homo, or a Pietà. It is a very small frame – only just over 10 inches sight size on the longer axis – and the trophies are in proportion; it must have been made for a domestic altarpiece and intended to hang over a prie-dieu, for private contemplation.

Plate 13 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 80 x 55, vue’; and on an antique looking-glass plate, Christie’s, London, 6 December 2012, Lot 8

Apart from the 16th century frames of the Puys d’Amiens, the military trophy frame shown in Plate 13 is one of the most breath-taking of all those which Roche gathered for his exhibition. It has a flat ground with a broken, scrolling outer contour and a rope moulding at the sight edge, and the field between is carved with layered weapons, arms and instruments. At the crest the head of Apollo, crowned with his symbolic sunflower, a rose, a narcissus and the fruits of peace, is held in a great sunburst, supported by trumpets, branches of oak and bay leaves, and by diagonally-laid banners, swords and spears; in the top corners are the heads of a bearded and a clean-shaven warrior on shields; and at the base is the head of Medusa, which the goddess Athena set on her own shield when Perseus delivered it to her, in order to terrify her enemies and turn them to stone.

From these various clues it can be seen that this is a frame which is describing, or expounding, or illustrating, the story of the war between the Persians and the Athenians, as described by Herodotus. Most of the Persian army under Xerxes (probably the bearded man, top left) had marched on Athens, but part of it made for Delphi, intending to plunder the temple there, which was sacred to Apollo. The Delphic oracle had foretold that Apollo would protect his own, but the people, being somewhat sceptical of how far his protection would extend, fled with their families and possessions, leaving only sixty men behind. However, as the enemy approached, thunder and lightning hit Mount Parnassus above the temple, bringing part of the mountain crashing down on the army; the Persian formation broke and the soldiers began to flee, helped on their way by the sixty men of Delphi and two mysterious and gigantic armed men who appeared on behalf of the Delphians.

Louis XIV trophy frame; details of heads at crest and corners

Meanwhile, in Athens, which was led by Themistocles (probably the clean-shaven chap, top right), the Athenian navy had been built up following a fortunately lucky strike in the state silver mines, providing Athens with the ‘wooden walls’ which the oracle of Apollo had said would protect the city (the oracle had also warned the Athenians to flee, and prophesied the destruction of the city’s temples by fire). Much of the vast Persian army was advancing on the Greek coast in its own fleet when it was hit by a marine storm, losing a number of ships (the head in the bottom right corner, with all its hair standing on end, may be Boreas, god of the north wind, who ‘blew and they were scattered’). Two naval engagements followed, in which the Greeks managed to out-manoeuvre the Persians, and took around 30 of their 200 or so ships. A further engagement was much less successful, whilst elsewhere Leonidas and his Spartans were betrayed, and failed to hold the pass at Thermopylae through which the Persian land army needed to move to reach Athens. In the event, Athens was evacuated by Themistocles, and taken by the Persians, who looted and burnt it. The tables were finally turned when the Greeks triumphed at the Battle of Salamis, losing only 40 of their warships to two hundred of the Persians, and far fewer men (the Persians couldn’t – apparently – swim). The fourth head on the frame may be that of Apollo’s oracle, foretelling both the destruction of much of Athens by fire, and its survival in the form of its people and the wooden walls of their ships.

When this frame was carved, most educated people would have known Herodotus’s histories, and would have deciphered its motifs with ease. It is difficult to imagine that such a powerful sculpture was originally envisaged as holding a looking-glass, but a painting is equally problematic; the most likely image which could have filled it would have been a panoramic view of the Battle of Salamis by a 17th century French artist. The photograph in Cadres français et etrangers… gives nothing away, although it is likely that the frame was empty when Roche exhibited it. It still bears on the back the exhibition label:

‘EXPOSITION INTERNATIONALE DU CADRE DU XV AU XXE SIECLE (AVRIL 1931) N. 137 GALERIE GEORGES PETIT, PARIS’

from which it appears to have been acquired by Baroness Marie-Cécile Fould-Springer, and out of whose family it was sold in 2003.

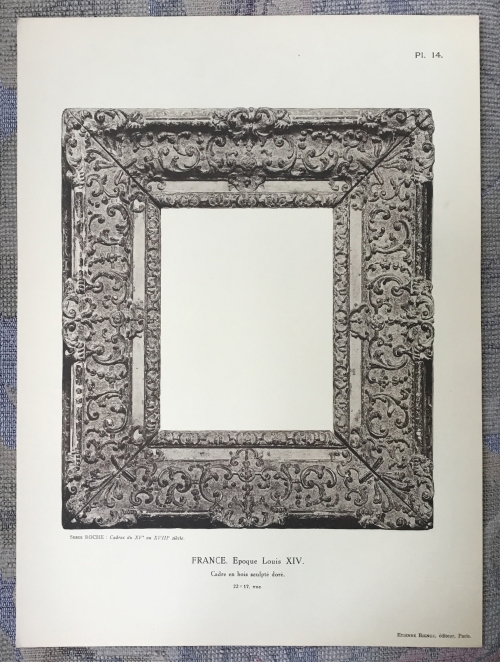

Plate 14 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 22 x 17, vue’

The frame in Plate 14 is a world away from its chronological neighbour; no trophies, no symbols, no large-scale pierced and undercut carvings; only a fully-fledged small piece of overall carving in shallow relief, in the calligraphic style which probably leaps first to the mind as an example of a Louis XIV frame. It is delicate and detailed, with fanned lambrequin corners, C-scroll and leaf bud centres, and a sight edge with more C-scrolling strapwork and leaf buds. It is interesting that Roche seems to have looked through the ogee and convex mouldings and the curving lines of the decoration, and found here an underlying composition of straight lines and severe geometry.

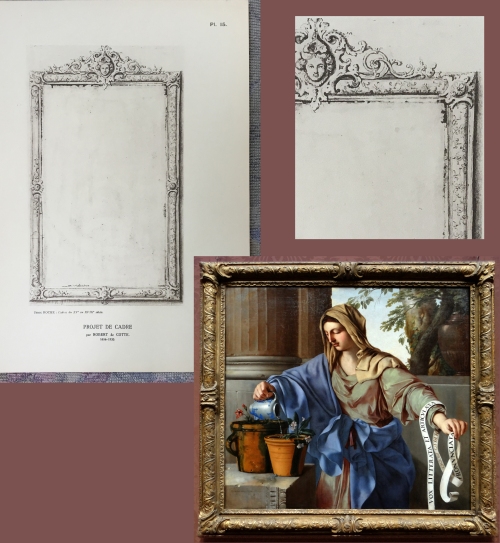

Plate 15 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Projet de cadre par Robert de Cotte. 1656-1735’; with Laurent de La Hyre (1606-56), Allegory of Grammar, 1650, National Gallery, London

He is as rigorous in the organization of his exhibition: here is a drawing by Robert de Cotte, widening the focus from the artists who carved the frames to one of the designers who provided a part of the inspiration and some of the models. Like so many frame-designers from the Renaissance onwards, De Cotte was primarily an architect, born in the year of La Hyre’s death in 1656, and becoming court architect in the 1680s, and later director of the Gobelins manufactory and the Bâtiments du Roi. He produced designs for everything from the façade of the bridge of the Rialto in Venice, and the layout of gardens in Versailles, to altarpieces, niches, arcades of boiseries in Notre-Dame, and looking-glasses . This particular drawing for a frame is hardly avant-garde; it is in the style of Louis XIII-XIV, of the mid-17th century; probably contemporary with or rather later than La Hyre’s painting. It is a less common variant of Louis XIII torus frames and Louis XIV convex profiles with graphic ornament, the strongly marked clasps at corners and centres giving a bold emphasis to the axes and diagonals of a painting. This uncluttered, architectural moulding is given a more frivolous lift by the pierced and scrolling fronton, with its tête espagnolette.

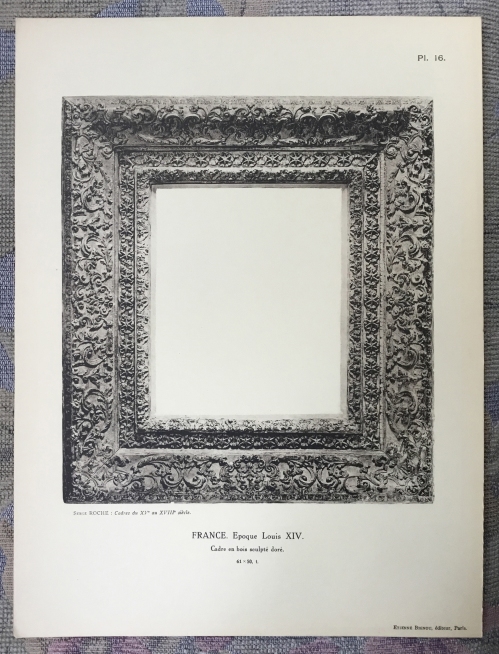

Plate 16 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 61 x 50, t.’

A straight-edged Louis XIV frame, with four orders of decoration, the back edge echoing the sight edge, and enclosing an ogee carved in slightly higher relief than in Plate 14, with finely recut scrolls, foliage and lambrequin corners. But it is the central frieze which is most interesting, since it is decorated with two twining ribbons, the alternate loops of which are carved with six-pointed stars. These are, like the small trophies and symbols noted on previous frames in the collection, most likely to have a religious significance, being connected with the Virgin as the Star of Ocean, as well as with the star of Bethlehem. Another French frame embellished with stars contains and was almost certainly made for a copy of Annibale Carracci’s Adoration of the shepherds, ex-Ickworth collection.The frame in Plate 16 has sadly lost its own Madonna and Child or Nativity; it formed part of Paul Levi’s collection, and was in the sales of his frames at Christie’s in the 1990s. It could originally have been the focus of another domestic space for prayer and contemplation, hanging with a prie-dieu in a study or bedchamber, or in a private chapel.

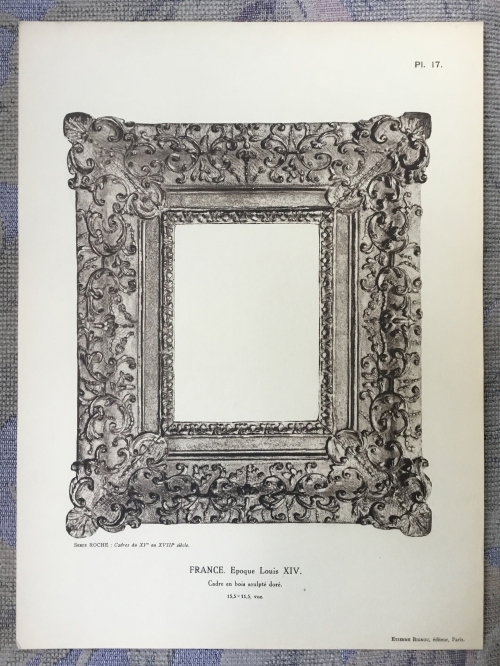

Plate 17 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 15.5 x 11.5, vue’

Plate 17 shows another Louis XIV frame, small and with projecting corners. The shallow carved foliate strapwork brings in further motifs – trailing husks and roses-à-tiges, the flowers which spout sprays of oversized stamens; the ground of the main ogee moulding is incised with cross-hatching in the gesso, and the ground of the corners and centres has coarser diapering. The frieze is sanded.

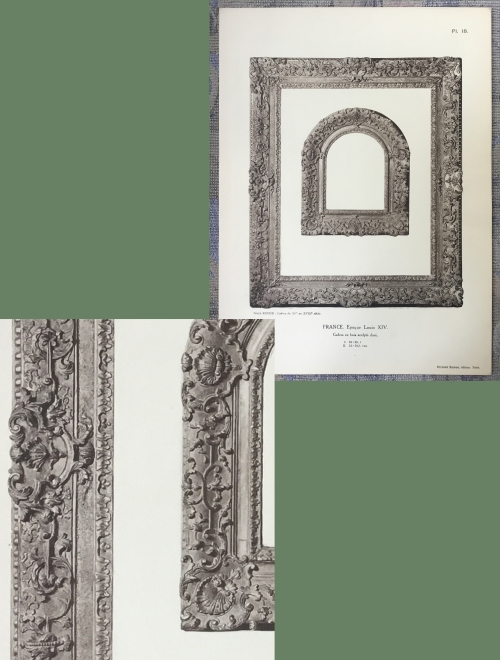

Plate 18 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadres en bois sculpté doré; I. 81 x 65, t.; II. 33 x 24.5 vue’

Louis XIV frame shown in Plate 18, carved and gilded oak, ogee profile, Bérainesque foliate strapwork with shell corners and centres, 55 x 46.5 cm. overall; EVE sale, 25 November 2011, lot 385

Louis XIV frame shown in Plate 18, carved and gilded oak, ogee profile, Bérainesque foliate strapwork with shell corners and centres, 55 x 46.5 cm. overall; EVE sale, 25 November 2011, lot 385

The small round-arched frame in plate 18 is one of a genre created most specifically in this period in France to display a carved crucifix, and reappeared in the art market in this guise in 2011 (the crucifix may or may not be the original belonging to this frame). Other versions of the design are taller, and have outset shoulders with a smaller round arch above. Both this and the larger rectilinear outer frame in Plate 18 show an increasingly sophisticated command of strapwork ornament, and, in the latter, an articulation of the different areas of the frame with the use of burnished grounds for the corner and centre cartouches.

Plate 19 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 22 x 217, vue’

A late Louis XIV frame, with a germ of the Régence buried within it, as the corner and centre cartouches extend a little, and ornament on the rest of the rails begins to think about shrinking back. The decoration is even more crisply defined, and the frieze has an enriched diapering cut in the gesso, giving a further subtle glimmer of light where it catches the engraved lines.

Plate 20 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Louis XIV: Cadre en bois sculpté doré aux Armes du Roi; 130 x 97, t.’

A royal trophy frame with the fleur-de-lys of France at the lateral and bottom centres, although the cartouche at the top centre has lost its motif. Most frames carved for portraits of the king were given the triple fleur-de-lys from Louis’s armorial bearings, but there are others with a single flower.

Louis XIV exhorting the Dauphin, ink & paint on vellum, c.1670; frame 35 x 20 ins (89 x 51 cm.), Sotheby’s, Paris, 6 July 2017, Lot 28

This lone fleur-de-lys on the apron of a rather grand, crowned frame is balanced at the top by a large, leafy capital ‘L’, and there are other frames which have a monogram made of an ‘L’ and a reversed ‘L’, often in the corner cartouches; so it is possible that there was once something similar on the top cartouche of the Roche frame.

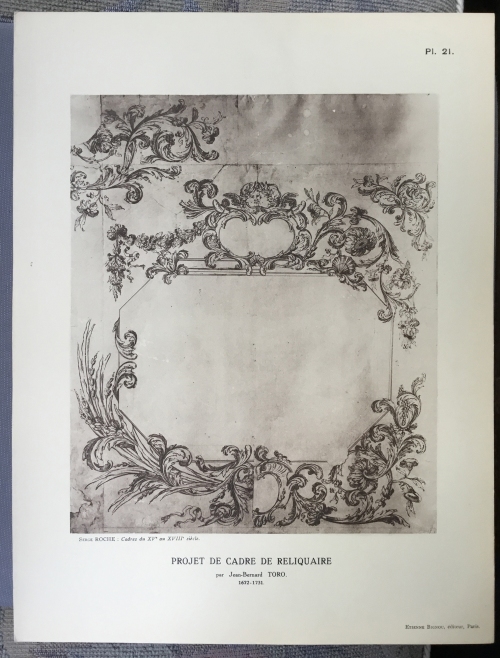

Plate 21 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Projet de cadre reliquaire par Jean-Bernard Toro. 1672-1731’

Another design for a frame: Toro had attended the Académie de Saint-Luc, created in 1705 to train painters, sculptors, wood carvers and ornemanistes; it provided a hot-bed for the development of the Rococo style under the supervision of men like Nicolas Pineau and François Roumier, which is apparent in the suites of designs Toro published from 1716-19, and in his drawings. The design for a reliquary frame in Plate 20 also shows the lighter, more delicate form of ornament which characterized the Régence, and which succeeded the heavier grandeur of the Louis XIV style. It gives two options for the frame, with fluid bunches of martyr’s palms on the left, and sunflowers (Christ) and scallop shells (John the Baptist; pilgrimage) on the right.

Plate 22 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Début de XVIIIe siècle: Cadre en bois sculpté doré aux armes du Duc de Bourgogne et de Marie-Adelaïde de Savoie; 28.5 x 18.5, vue’, and detail

Plate 22 shows a second royal trophy frame: this time with the arms of the Dauphin of France – the grandson of Louis XIV – and the Dauphine, his wife and mother of the future Louis XV. The fronton, with its grand scrolled cartouche, contains the arms of the duc and of his wife and is supported by a cherub’s head. The crown above it has sadly lost most of the fleur-de-lys which decorate it, but the two dolphins, for the prince and princess, remain in scaly, large-lipped splendour. Their presence means that this frame must have been made after the death of the previous dauphin, father of the duc and son of Louis XIV, which happened in 1711. In 1712 both the new dauphin and Marie-Adelaïde caught measles and died, thus dating the frame quite precisely. It is difficult to speculate what it might have held – the sight is only a fraction over 11 inches high (28.5 cm.), and is quite narrow. Perhaps it was made for a miniature full-length of the dauphine in her princessly regalia, a pendant to a portrait of the duc.

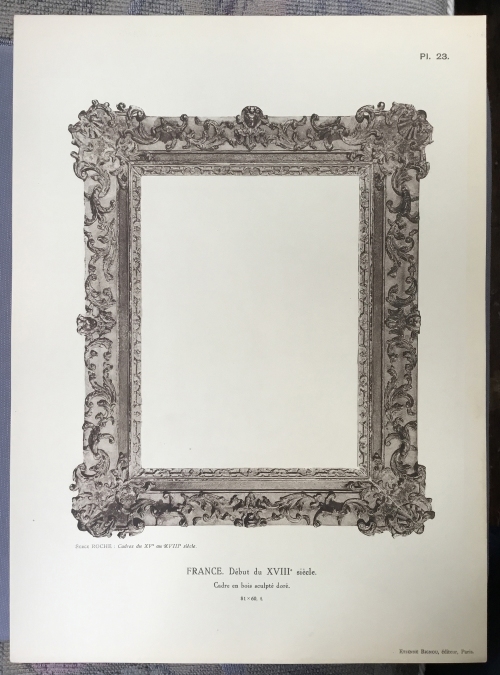

Plate 23 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Début du XVIIIe siècle: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 81 x 60, t.’

The frame in Plate 23 shows the Louis XIV style loosening and opening out into the decorative composition of the Régence, whilst the ornament still takes the slightly more robust approach of the 17th century, and the corners are shallow and dished, with low-relief shells. At the sight edge, the ornament is fining down into a flickering dance of very slender strapwork.

Plate 24 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Début du XVIIIe siècle: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 137 x 105.5, vue’; and a corner of the Régence frame (c.1715-30) on Ludovico Carracci (c.1555-1619), La Vierge et l’Enfant, c.1616-19, o/c, n° Inv. 184, in French giltwood Régence frame, c. 1715-30, Musée du Louvre

The Régence style is even more apparent in Plate 24: here, the corners have taken on the convex scrolled cartouche form with its central boss which is so characteristic of this style, and which can be seen in the beautiful 18th century frame given to Carracci’s Madonna and Child in the Louvre. The centres of Roche’s frame are held in long, scrolled acanthus leaves, veined with tiny beading, which are another typical motif – but the centres themselves have a surprising halo, like a goffered lace ruff, of the sort which normally frames a tête espagnolette.

Plate 25 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Régence: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 61 x 50, t.’

This is a fully-fledged Régence frame, with burnished, fret-like strapwork on a small, fine scale, and large corners (with bosses held in wreaths of palm leaves) which extend at the top into the spandrels of the shaped arch. This shaped inner contour and the palm leaves suggest very subtly that the contents might originally have been another domestic altarpiece – a crucifixion, perhaps, or the picture of a saint. Earlier, more overt signs – the instruments of Christ’s Passion, symbolic flowers, etc. – have melted away into a form of decoration which is all but purely ornamental.

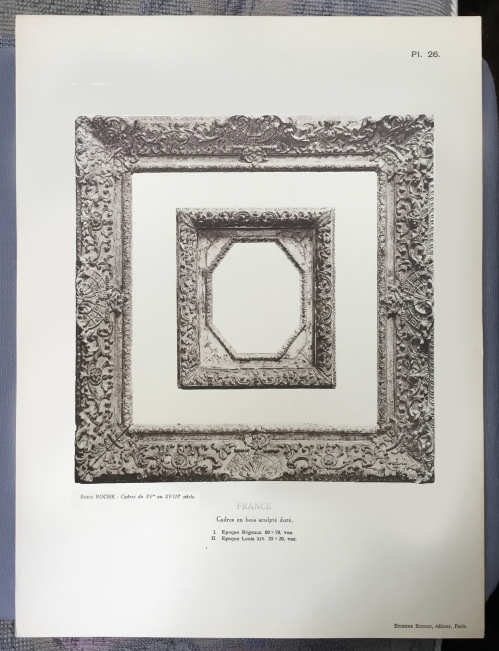

Plate 26 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Cadre en bois sculpté doré: I. Epoque Régence: 80 x 70, vue; II. Epoque Louis XIV; 25 x 20, vue.’

A small Louis XIV convex frame with very battered spandrels sits inside a larger piece which still seems to be in transition to the Régence. The most overt sign of its transition is the fanned trellising, enriched with florets, which surrounds the scallop shells at the centres, and the small knulled bands above them.

Plate 27 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Régence: Cadre en bois sculpté doré; 61 x 50, t.’

Another fully Régence frame, with a linear contour, large bosses at the corners, and fanned lambrequins above them. The bosses are held in minute chains of ovolos, contrasting with their own size. There is space around the graphic, dancing strapwork on the rails, and a feeling of lightness, elegance, and restraint. The geometric lines of the composition are clearer, and demonstrate what Roche must have seen beneath the skin of finely-carved decoration, and what he could import into his own very 20th century designs.

Plate 28 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Régence : Cadres en bois sculpté doré: I. 73 x 60, t.; II. 27 x 22, t.’

Of the two frames in Plate 28, the outer frame is a Régence work, whilst the small frame in the centre is beginning to show signs of the next stylistic change – more straight-edged Louis XV than Régence, with its spiral-bound top edge and large projecting corners, which are fringed with fanned lambrequins, ready to morph into rocailles. The larger frame equates in size to a half-length British portrait (misleadingly called a ‘three-quarters’) , and has a small coronet at the top, indicating that it originally held the likeness of a nobleman or -woman. It, too, has signs of moving on from the pure linearity of the Régence, as the little knulled bars down its contour curve themselves into the foretaste of an embryonic swept edge.

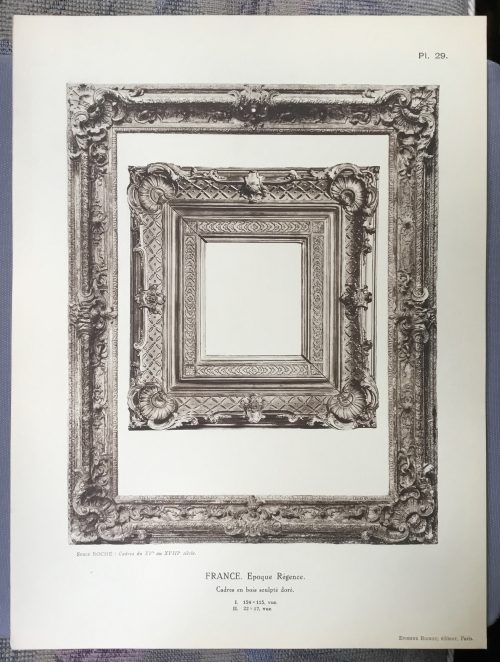

Plate 29 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Régence : Cadres en bois sculpté doré: I. 154 x 115, t.; II. 22 x 17, t.’

Plate 29 returns to a pair of frames in the full flower of the Régence style: the outer (5 feet high at the sight edge), with a strong linear cast which includes the lozenge-shaped strapwork in the hollow, with its demi-centres of raised bosses; it also has centres which clasp the top edge, contain further bosses, and erupt in little plumes of fanned lambrequins which cross the frieze and merge with the sight edge. The inner frame is even more notable for its straight mouldings, a frieze diapered in the gesso, and centre clasps.

Degas (1834-1917), Dancer onstage, c.1877, gouache/ paper (6 ¾ x 8 3/8 ins; 17.1 x 21.3 cm.) on board (7 x 9 ins; 17.8 x 22.9 cm.), acquired 1973, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, montaged into frame from Plate 29 of Cadres français et etrangers…

It may perhaps be the frame in which Degas’s Dancer onstage is recorded as arriving at the Met. in 1973. This painting belonged to Alexis, the brother of Henri Rouart (friend of Degas, collector and artist), and passed to his son Henry, who sold much of the collection which came to him in the 1930s – around the time of Roche’s exhibition of frames. The catalogue entry on the museum website notes that:

‘The frame in which this picture entered the museum was exhibited in 1931 at the Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, in the “Exposition de cadres français et étrangers . . . ,” no. 198 (as “Cadre bois sculpté doré. Style Régence. XVIIIe siècle. 21 x 16,” lent by M. Serge Roche)’

This is the nearest frame in size in the catalogue, although the frame on the Degas may, more probably, have been in the exhibition but not in the catalogue.

Plate 30 of Cadres français et etrangers…: ‘Epoque Régence : Cadre en bois sculpté doré: 73 x 60, t.’

The final plate in this section of the book is a very rich example of Régence carving, with a spiral ribbon at the back edge, an enriched gadrooned and fluted top edge, a ribbon-&-stave, and a shaped and cut-out contour of tiny shells at the sight edge. Over all these linear mouldings sit great flaring corners and centres, with accretions of ornament which reach across the width of the rail and bleed onto the area of the canvas in the form of lambrequins and shells. The posies of flowers which support them are carved in high relief, and the ground of the various areas is textured in the gesso, for maximum contrast with the burnished areas.

The collection which Roche assembled for his exhibition included many frames which would now be treasured as exemplary pieces of giltwood sculpture, but which, at the time, must have seemed curiosities or decorative redundancies, only useful to clothe a naked painting and make it more saleable – as in the case of the Degas: how much easier to get an American client to invest in a painting in this style if it were presented in an antique gilded frame, rather than one of Degas’s reeded white or coloured mouldings. Strangely, the latter were closer in their pared-down geometry to Roche’s own frames, yet those developed from his enthusiasm for the Baroque treasures he presented in the Galerie Georges Petit in 1931.

*************************

With grateful thanks to Andrew Levi for all his help with this article

Part 2 is here

**************************

Top left: 17th -18th century ebonized octagonal looking-glass, Netherlandish or (?) Italian; top right: Alessandro Algardi (1598-1654; after), Virgin & Child, c.1750, Bologna, V & A; bottom: Serge Roche (1898-1988), octagonal looking-glass with fantastic animals, probably by Max Ingrand (1908-69), 1933, ex-Galerie Chastel-Maréchal

*************************

[1] Patrick Mauriès, Serge Roche, Paris, 2006, to accompany the exhibition of Roche’s work at the Galerie Chastel Maréchal in 2006. This book is unpaginated, so it is redundant to try to cite particular pages in the footnotes: therefore, any factual information on Roche, his career and interests may be taken as coming from this source

[2] The early 16th century illuminated manuscript, Chants royaux en l’honneur de la Vierge au Puy d’Amiens, Bibliothèque nationale de France, published online at Gallica BNF, contains miniatures of 47 of the altarpieces (without their frames), painted by Jacques Platel; this MS was presented in 1518 to the queen mother, Louise de Savoie, by members of the Confrérie. The oldest surviving altarpiece is Le sacerdoce de la Vierge by the Maître des Heures Collins of 1438 (99x 57 cm.), commissioned by Jean du Bos, a marchand-mercier, now – minus its frame – in the Musée du Louvre. The collection within the cathedral has shrunk to a minute ‘chapel’, clustered around a pillar, where a mass dedicated to the Virgin is still celebrated

[3] An exhibition on ‘Les Puys d’Amiens’, scheduled for 2020, has been rearranged for 20 March–20 June 2021 at the Musée de Picardie. Much of the information on the altarpieces in this current article is taken from a paper given at a conference on the Puys d’Abbeville and Amiens in 2016 by François Séguin

[4] In the note on dimensions in the caption, the ‘t’ for ‘totale’ must be a mistake for ‘vue’, since the Titian is 81.2 x 66.3 cms, and thus fits the frame as though painted for it

[5] Collection of Andrew Levi

[…] siècle [1]. For a brief introduction to Roche and Petit, and for the first section of frames, see Part 1. Both articles are written in collaboration with Andrew Levi; the frames in both are all French, […]

LikeLike

Dear Lynn

I do hope you, Adrian and Toby are as well as can be in these surreal times. Judging by your astonishing additions to the Frame Blog you must be working round the clock. This is a belated response to say how brilliant the Irish frames story is – some works as frothy as Guinness – and now your opening up the world of Serge Roche for all to see. Amazing how he managed to gather so many masterpieces together for the 1931 exhibition. One would have hoped the whereabouts of more could have been found by now making the NG Titian one so special. Your descriptions are superb and I now know more from plate 13 about the Persians and Athenians than I did last week! A truly breathtaking work. I guess you’ve enhanced the value of all copies of his frame folio! I wonder what SR would have thought of Frameworks! How interesting to be working with Andrew Levi on this. What career has he pursued?

Mary said you’re getting together soon so she will update you on news – we’re surprisingly busy I’m glad to say – and looking forward to finalising our new lease.

All love

Paul x

PS Home grown. This is what happens when Mr Nosey eats too many tomatoes!

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such fun looking-glasses!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Lynn, thank you so much for the article! Very interesting and important material for me!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Oksana –

Sorry, I have only just seen this, but am so glad if it is helpful. I hope to publish more of Roche in the future!

LikeLiked by 1 person