17th – 18th century silvered & lacquered frames from Barcelona

by Gema de Cambra Florensa

Introduction

This article attempts to describe, identify and locate the origin of a group of unusual Spanish Baroque frames. Several examples of these architrave, flat or plate frames, finished in silverleaf, lacquered, and decorated in monochrome with scrolling foliate ornamentation on the frieze, have passed through the author’s workshop. They date from the 17th and early 18th centuries, share identical construction methods, were made from the same materials, and have very similar decoration. Since a significant number originated from the art market in Barcelona and its surrounding area, it is natural to associate them with this region.

Silver mecca reverse architrave frame containing the original painting, private collection; restored by the author

The distinctive evolution of the Barcelona guild of gilders, compared with those of other cities in the kingdom of Spain, the economic prosperity of the city, the demand for luxury items, and the fact that these frames have recently been appearing in Barcelona – all make it reasonable to assume that they originate from the workshops of the city’s master gilders.

Since this style of frame was not considered representative of the Spanish Baroque, it never underwent a revival in the 19th century, and the frames which have survived are undoubtedly original and representative of a specific region and a particular historical and artistic period. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that they were manufactured in Barcelona, capital of Catalonia and part of the kingdom of Spain.

Initial investigation

The suspicion that these frames were local products of Barcelona grew from personal experience in a restoration workshop in the city, where several examples of the same type arrived at various times. As noted above, the methods of construction, materials, finish and decoration they displayed were all identical. They were all fairly small in size, so they were most probably intended for domestic settings. They were treated as individual objects, arriving separately and at random, and, except for this single example, there is no evidence as to what paintings they might originally have housed.

Silver mecca reverse architrave frame containing the original painting, and detail of top right corner, private collection; restored by the author

This example is contemporary with the painting it holds, and came from the private collection of a wealthy bourgeois family in Barcelona who, like many others between the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, invested part of their income in paintings and antiques. This type of collecting was, in most cases, closely linked to the local arts of Catalonia.

However, searching for information on this particular type of frame, mainly in relation to the decoration of its surface, both in specialized bibliographies and in publications on the history of frames, proved unsuccessful. Although it was not a common type of frame on the international market, some related examples were found which were described generically as ‘Spanish, second half of the 17th century’. Given that a significant number of them have emerged from the art market in Barcelona and its surrounding area, it’s tempting to link them to this area. However, justifying their origin based solely on where they have appeared needs more evidence to prevent it from being a leap to a conclusion[1].

To discover whether these frames were of Catalonian manufacture, and made more specifically in Barcelona, it is essential to understand the history of framemaking and selling in the region. Unlike elsewhere in the Spanish kingdom during the 17th century, professional gilders working in Barcelona (mestres in Catalan) were permitted not only to gild frames but also to decorate and sell them in their own workshops. This fact might be the key we are looking for. Barcelona was a wealthy city at that time and many of its inhabitants were thus able to buy paintings and frames at the shops of local gilders. Julien Lugand’s research, in L’ofici de daurador a Barcelona (1599-1834) [The gilder’s craft in Barcelona], has been fundamental to understanding the evolution and importance of these workshops in Barcelona.

Unfortunately, most of the surviving documentation from the period – wills, inventories, and lawsuits from the 17th and 18th centuries – is not very precise. Where they occur, mentions of ‘guarnicions‘ (frames) are vague and generally unhelpful for accurate identification, as the purpose of such documents was not to provide detailed and meticulous descriptions. In a broad sense, given that frames were seen only as the accessories of paintings, what was identified was usually only the colour, whether there was a gilded finish or whether ‘corladura‘ (lacquered silver) had been used, and to note whether, in addition, the frame was carved.

Technical description of the frames

All the frames recognized as being part of this group shared the same method of assembly, a similar profile, decorative technique and materials, but different versions of the painted ornament have been recorded.

Diagram and reverse of one of the frames in question, showing the joint used to assemble the four rails

The method of assembly: in all the frames, the lateral elements are joined to the horizontal elements by means of a half-lap joint (known in Spain as a ‘T-shaped half-lap joint’ or ‘palm joint’). The horizontal element of the half-lap joint does not extend to the outer edge of the vertical element. This joint is characterized by its retaining the strength of all the elements involved, so the carcase of the frame required no reinforcement with nails.

Neapolitan reverse frame, mid-17th century, carved poplar wood, gilded on orange-brown bole, sight: 12.3 x 8.5 cm., overall size: 28 x 23.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York; Robert Lehman Collection: 1975.1.2140; profile & joint diagrams: Timothy Newbery

Whilst the joints can be related to late 17th century Spanish frames, there are of course other examples, such as the Neapolitan reverse frame in the Lehman Collection, described by Timothy Newbery, which has identical joints. Southern Italy was closely linked to eastern Spain (Catalonia, Aragón and Valencia) due to the commercial and political relations existing between them [2].

The frames are all made of common pine wood (detail above).

The mouldings on the façade of the frame are mitred, glued to the carcase and reinforced with iron nails (top right). The sight moulding is similarly attached, and also forms the rebate of the frame (bottom left).

All the frames have a reverse profile, sloping back towards the wall from the highest point – at the sight edge (on the right, here).

There are two variations of the outer contour:

a) There is no moulding attached at the back edge; the frieze ends in a rounded edge, with an inscribed groove around the contour.

b) There is an ornamental moulding attached to the back edge of the frame.

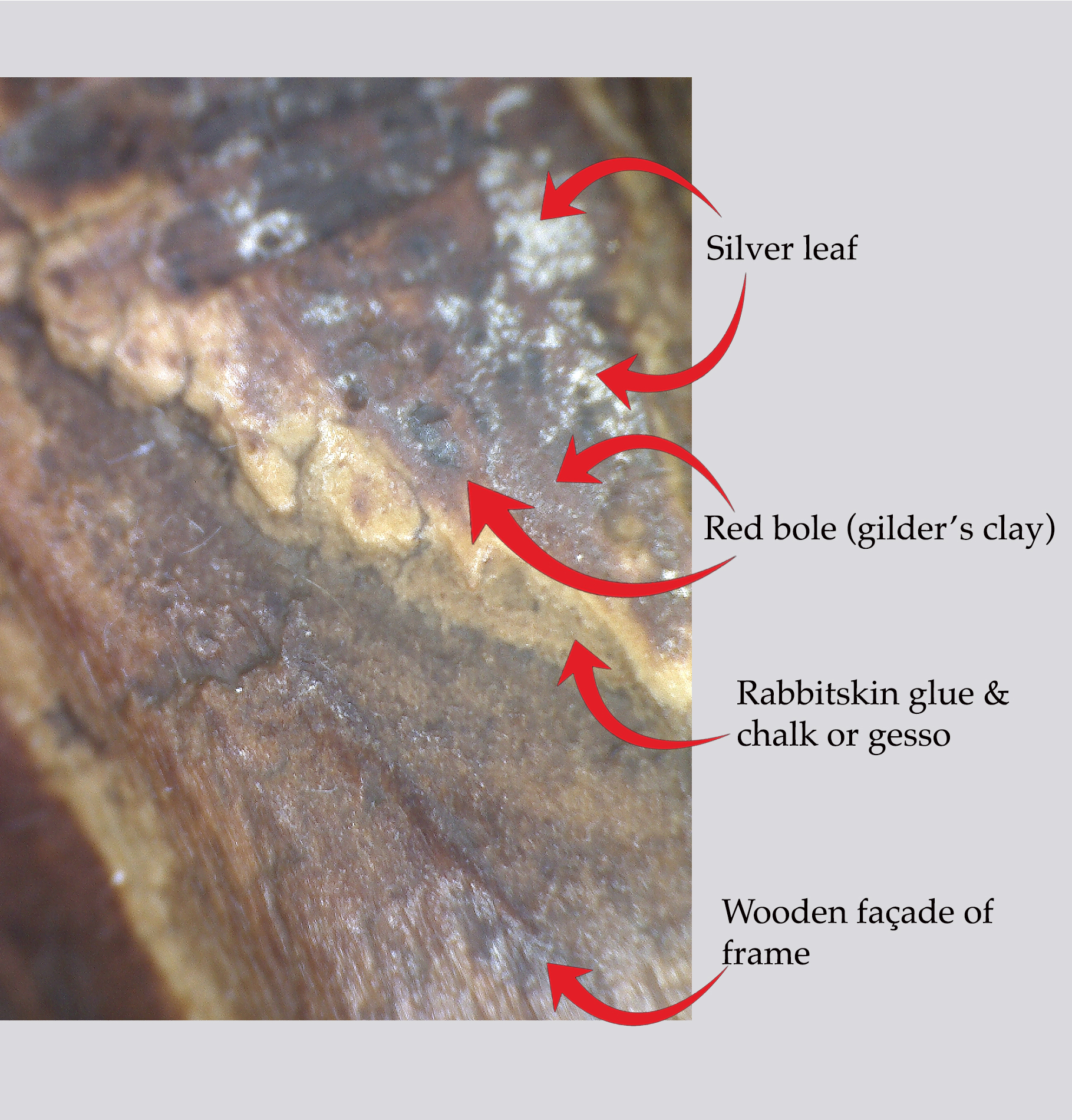

The decorative surface begins with thin layers of substrate (rabbitskin glue with chalk and red bole) laid on the wood; the bole is activated with water and followed with silverleaf; when dry, this is burnished.

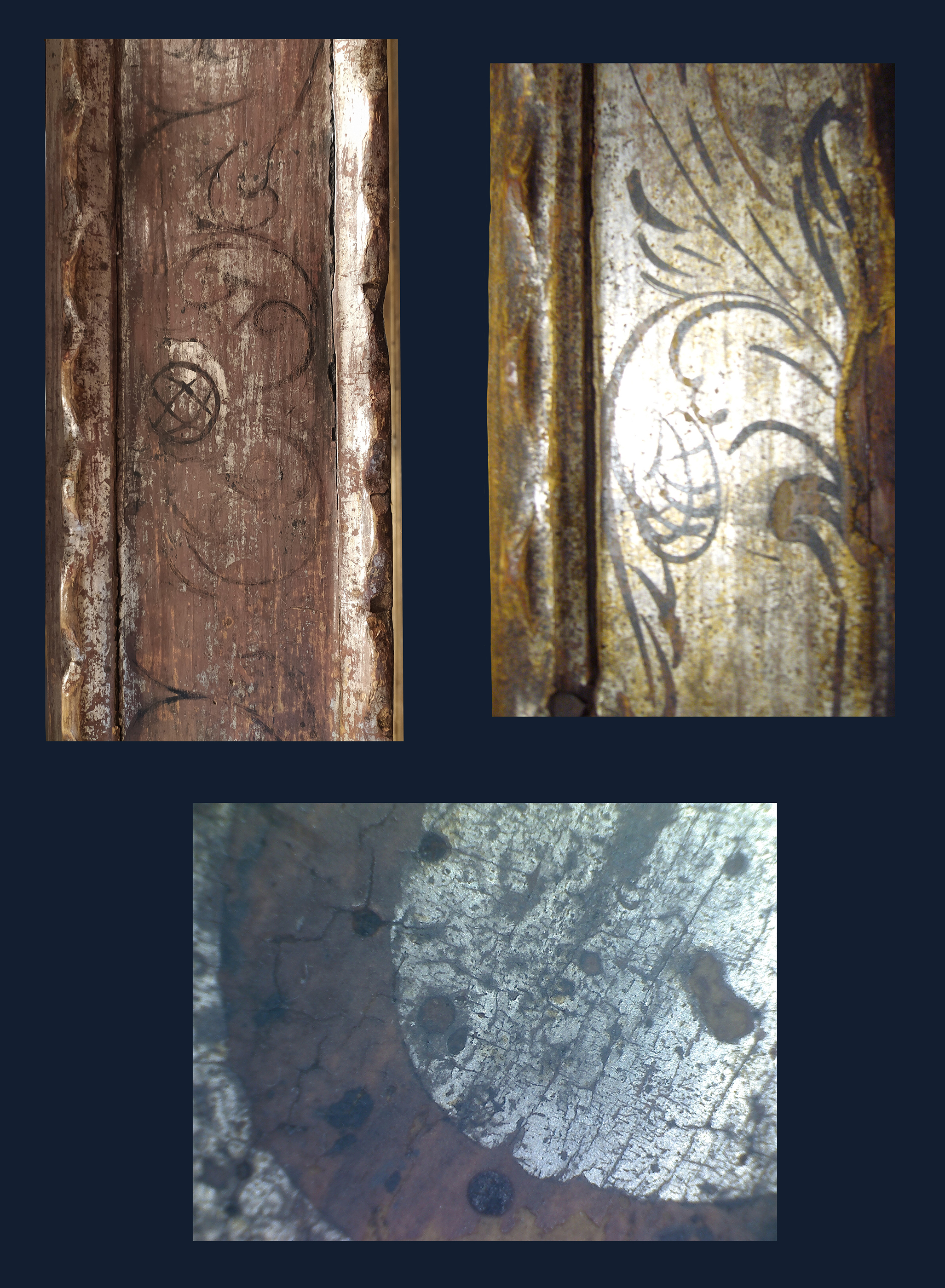

Two examples of friezes with scrolling foliate decoration, and below them a close-up detail of a brushstroke which has removed the silverleaf beneath it

The scrolling foliate decoration (referred to as ‘cogullo‘ in documents) is painted onto the surface of the burnished silver frieze with a fine brush, probably using ink. The use of ink would explain the corrosion of the silver, which has exposed the colour of the bole, since the ink commonly used from the 5th century onwards is made from ground-up oak (or other) galls, contains tannic acid, and so eats away the silver leaf.

An unusually well-preserved coating of golden shellac on a Spanish frame, 63.5 x 86 cm., in the collection of Antike Rahmen, Berlin

Examples of frames where the shellac has either been removed (top, Schoeni Frames, Zurich), or has darkened (bottom, restored by the author, LAB ART, Barcelona)

When the decoration has dried, the entire surface of the silvered and painted frame is coated with yellowish shellac, or lacquer, to achieve the so-called ‘golden mecca’ effect. Ageing and renewal of the shellac over the years cause it, in most cases, to darken, thicken and harden. Unfortunately, very few frames retain the original yellow coating in good condition [3].

The decorative finish

Sicilian Rococo console, mid-18th century, silvered limewood with marble top, 104 x 183 x 78 cm., J. Paul Getty Museum; unrestored (top) & restored with coat of yellow lacquer (below)

Silver mecca, or lacquered silverleaf, was commonly used on furniture from Catalonia, Valencia, Naples and Sicily, and although it is widely accepted that Italian and Spanish frames are closely related,

‘…to such an extent that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between them …’[4]

it is likely that this type of flat or architrave frame, its frieze decorated in black on silverleaf, is not Neapolitan, and – as will be argued – is closely related to the gilding trade in Barcelona.

A small reverse polychrome and punchwork frame (top, left & right), and the back, showing the joints (Peter Last, Bristol); a giltwood reverse frame with corner-&-centre decorative motifs (bottom, left & right), and a detail of the back

Although there are other frames of the same relatively small size which share the same structure, technique, and materials, the use of colour in their decoration and its frequent concentration in the corners of the frames exclude them from the focus of this article. However, to give context to this research, images are included here of some of these different surface finishes on frames dating from the 17th and 18th centuries, which otherwise share an identical makeup.

17th century black and parcel-gilt reverse frame from Catalonia, and back with joint (restored by the author, LAB ART, Barcelona)

Silvered reverse frame carved overall, and back with joint (LAB ART, Barcelona)

17th century Catalan carved giltwood reverse frame with polychrome estofado scrolling foliate corners, and back with joint (top, left & right; LAB ART, Barcelona); early 18th century reverse frame, with polychrome faux marbled panels probably added later, and back with joint (bottom, left & right; restored by the author, LAB ART)

Late 17th-early 18th century silvered frame, perhaps previously lacquered (left); late 17th-early 18th century Aragonese or Catalan reverse parcel-gilt and polychrome frame with green marbled back edge, red marbled frieze, and painted yellow scrolling foliate corners (right); both having the same joints visible on the reverse as the other frames illustrated; both restored by the author, LAB ART

There were many kinds of finish on similarly flat or architrave profiles – whether black, black and parcel-gilt, marbled (‘jaspiats‘ in Catalan) or otherwise decoratively painted – from the late 16th to the mid-18th century, and they almost certainly came from the eastern regions of Spain – Catalonia, Aragon and Valencia.

Were our particular silver mecca frames manufactured in Barcelona?

Detail of the 17th-early 18th century silver mecca reverse architrave frame which opened this article, private collection; restored by the author, LAB ART, Barcelona

By analyzing the group of frames in question, it was hoped to answer the question, could they have been manufactured in Barcelona, in the workshops of master gilders, and sold in their shops between the 17th and early 18th centuries? In pursuit of this idea, the methods of production control employed in the craft of gilding in Barcelona have been thoroughly investigated, and the socio-economic context in the city from the mid-17th to the first half of the 18th century has been considered.

The gilder in Barcelona

Gilding, like any trade, was organized and structured – before the Industrial Revolution and under the Ancien Régime (i.e. from the 15th to the early 19th century) – by guilds which, at the local level (that of cities), established, regulated, and guaranteed the proper practice of the profession.

‘Carpenter ‘, plate 73, Jan Luykens, Afbeelding der Menschelyke Bezigheden, 1694, Internet Archive

Framemaking as a discrete trade did not exist; it was primarily a sub-branch of furniture-making, and could involve (depending upon the type of woodwork and surface finish required) carpenters, sculptors, joiners, gilders and painters. At that time, each of these trades was regulated, delimited and structured by its own guild. To understand how it worked, it is necessary to examine the evolution of the gilding craft (art de daurar or doratura) in Barcelona, as distinct from other cities in the kingdom of Spain – a study based on the detailed and exhaustive research published by Julien Lugand [5].

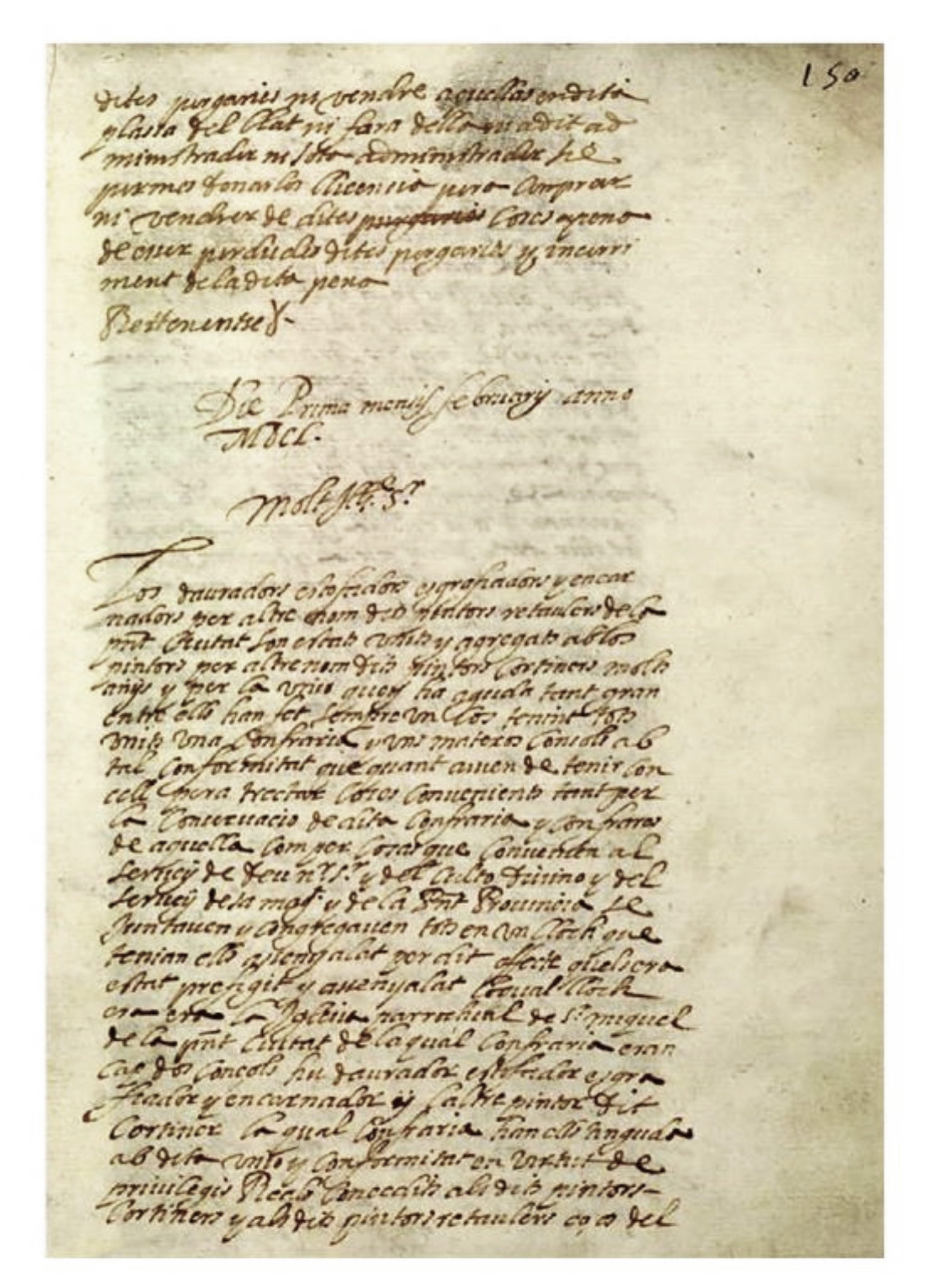

The Barcelona ‘Ordinances’ of 1599 recognized gilding as a separate activity, whereas in other Spanish cities there was no distinction between painters and gilders (a painter-gilder category existed allowing its members to practise both professions). Gilding achieved its own autonomous guild in Barcelona in the mid-17th century, meaning that access to the trade would be regulated through control of training, apprenticeship, and practice, and was also protected against incursion by gilders from outside the city. Ordinances, lawsuits, and agreements give an insight into how the gilding trade was organized.

Ordinacions de la confraria dels dauradors, 1 February 1650, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

Throughout the second half of the 17th century, the independence of doratura in Barcelona became increasingly well-defined, and the scope of its practice was laid out through various agreements. To practise the trade of gilder, own a workshop and a commercial shop in Barcelona, it was necessary to obtain the title of mestria or master. Obtaining this title through an examination was a regulatory tool which controlled access to the profession, but it also facilitated access for family members, since the examination was cheaper for them.

Master gilders, members of the guild, were permitted to gild wood and to burnish gold and silver. In addition to altarpieces, the various items they could gild were specified: carriages, cabinets, banners, coats of arms, picture frames and works on paper [6]. Gilded objects made in the workshops of masters could be sold in their own commercial shops.

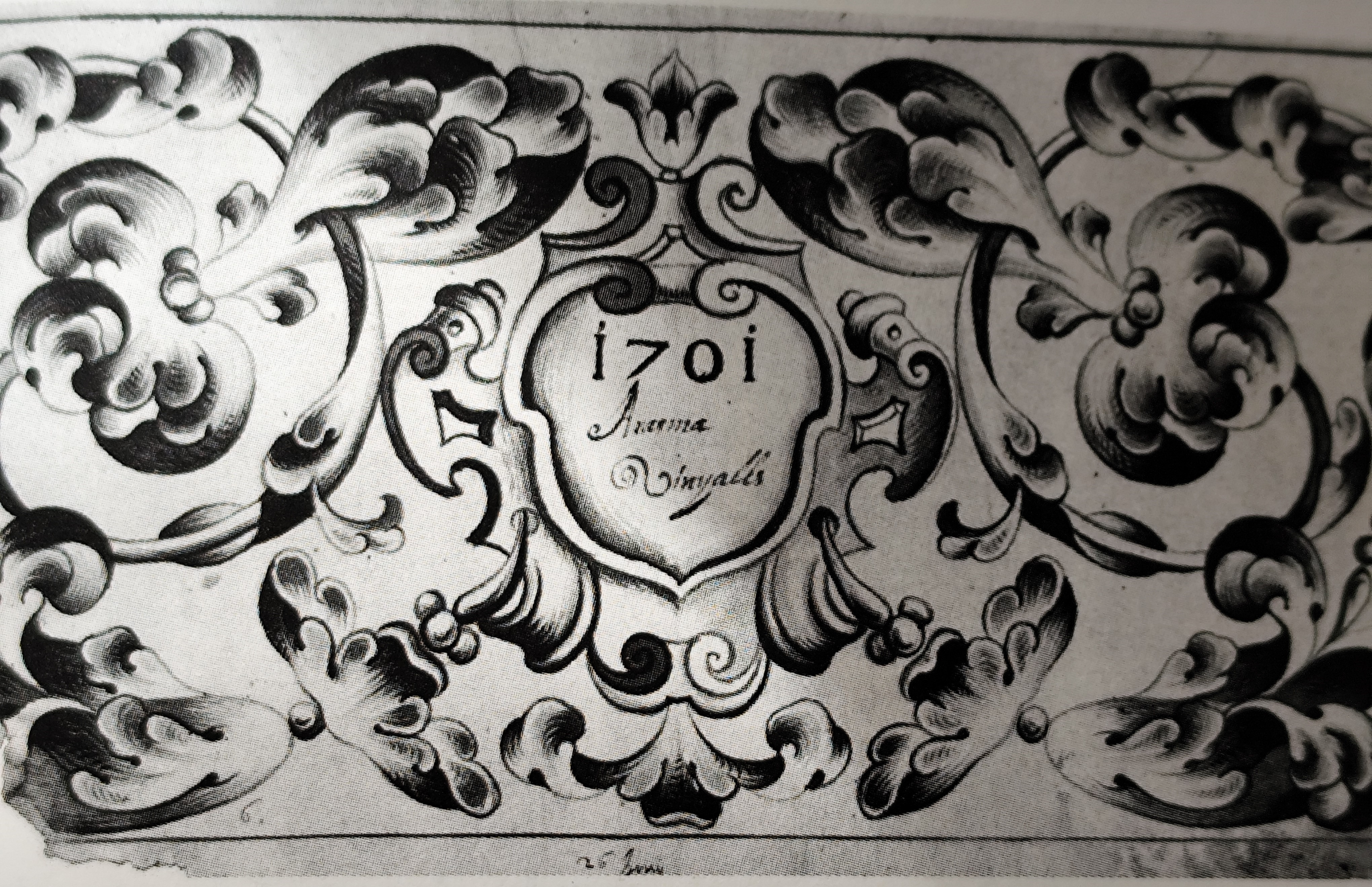

Detail of the passantia by Erasme Vinyals, 1701, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

The master’s examination also assessed the quality of the applicant’s talent for decorative drawing. The surviving drawings of the passanties, part of the entrance exams for the master’s degree, are preserved in the Barcelona Historical Archive; they demonstrate the skills which master gilders were required to possess in depicting fullatges – the scrolling foliate motifs, also known as cogullo, which could be painted on the frames they worked on. The fullatges, applied to the frieze of a frame, encapsulate all the accomplishments required in a master: skill in all the stages of gilding, the ability to design extraordinary complex and exquisite foliate flourishes, and mastery of drawing with a brush.

Detail of the passantia by Onofre Boet, 1701, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

Master gilders, having proved their ability to design and draw, were then invested with the authority to decorate frames and sell them in their shops. The joinery of these very plain, flat frames was simple and did not require additional skills in carpentry, woodcarving or sculpture. In the case of more complex frames which did require carved ornament, clients could commission them from sculptors (carpenter-sculptors); these were minor works which sculptors’ workshops accepted to increase their income, and the clients would later have them finished by gilders (such frames do not form part of this research) [7].

Master gilders could sell in their shops only the guarnicions or frames which they had gilded or silvered in their own workshops. In a lawsuit instigated against the gilder Pere Vinyals because ‘he has a framed painting for sale in his shop’, Vinyals defended himself by claiming,

‘…that the picture was painted by his brother, a painter, and that the frame was gilded in the workshop [a l’obrador s’ha daurat la guarnició ]…’ [8]

and that therefore it was legal for him to sell it.

A small-scale silver mecca frame, restored by the author, LAB ART, Barcelona

It appears, then, that the frames which are the subject of this article may have been commissioned originally by gilders from carpenters’ workshops, and afterwards not only finished and decorated in the gilders’ workshops but sold from their own shops. The dimensions of the frames were suitable for display in the shops, and also a convenient size for domestic interiors (mostly they were roughly 60/70cm x 80/90cm); moreover, they were affordable by ordinary home-owners. By selling what they produced in their own shops, the gilders could increase their income, since the payments made for altarpieces commissioned by the church (for example) often took long periods to arrive.

Barcelona did not attract artisans from abroad or from the rest of the Spanish kingdom, as the protection from outsiders afforded to the craft discouraged such movement. Because the regulations governing access to the gilding trade also favoured family members, Barcelona became a closed shop, where very few foreign gilders could establish themselves. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, two-thirds of the gilders were born in the city, and the remaining third came mainly from the rest of Catalonia. Only four masters arriving from Roussillon (south of France) and one from the Aran Valley (north of Catalonia, Spain) have been recorded.

The limited distribution of frames with these decorative designs is almost certainly due, first to the fact that the frames sold in the shops of master gilders were purchased fairly quickly by wealthy citizens of Barcelona, and second to the protection afforded to the gilding trade, which hindered the movement of craftsmen and also dissemination of the various designs.

Barcelona: the social and economic context during the 17th and first half of the 18th century

Prosperity in Barcelona began to rise in the 16th century, and the standard of living for the general population improved throughout the 17th century. Because of this, more people had access to more and more goods, and it is clear that domestic interiors became increasingly opulent [9].

At the beginning of the 18th century, when Carlos II held his court in Barcelona, the city teemed with musicians, artists, and Austrian exiles who had been forced to leave their homes in Valencia, Aragon, and Castile. Indeed,

‘the Barcelona of the Austrian court can be associated with foreign nobles and others who came seeking favours…’ [10]

The taste for luxury in an economically dynamic city encouraged the acquisition of goods, both imported and locally manufactured: luxury always being coveted by the wealthy, whether foreign or native. Although Barcelona suffered the horrors and consequences of war between 1691 and 1714, it recovered quite quickly[11] and soon experienced a boom in commercial activity. Records exist of orders and purchases of furniture and decorative objects, and the aristocracy devoted themselves to collecting paintings and decorative items in the 18th century [12]. Paintings of secular subjects became more common – portraits, hunting scenes, still life paintings, landscapes and marines – and there was a

‘…significant increase in frames made with the technique known as colradura‘ [13].

It was often noted in the relevent document that these frames were carved (‘silver mecca carved frame’), which do not concern this article; however, they might simply note, ‘silver mecca frame…’ Are these last frames the subject of our inquiry?

Conclusion

Silver mecca reverse architrave frame containing the original painting, and detail of top right corner, private collection; restored by the author

It is likely that the painting and frame which appeared at the beginning of this article – an original pairing of picture and setting – are native to the city of Barcelona, and date from sometime during the second half of the 17th and the first half of the 18th century.

It is also reasonable to assume that the larger group of lacquered silver frames, with their simple flat profiles and scrolling foliate decoration, most of which have been found in Barcelona and its surroundings, came from the workshops of the city’s master gilders. Theirs was not a widely distributed pattern, due to the limited access which foreign gilders had to Barcelona, which explains the lack of diffusion of this style; also because it appears that their production and sale were aimed at a wealthy local clientele who lived in the city and wanted objects of this type to decorate their homes.

Frame with the shellac removed (Schoeni Frames, Zurich)

Given their fragile surface and high susceptibility to deterioration – the lacquer darkening and the silver oxidizing – it can be assumed that many of these frames have undergone a surface refurbishment in the years since they were fashionable, adapting to prevailing trends and tastes. Since this style of frame was not considered representative of the Spanish Baroque, it was not reproduced later on, and the frames which have survived are undoubtedly original and representative of a specific region and a particular historical and artistic period.

Further research is needed to obtain more evidence, in order to confirm this hypothesis.

*********************************

Gema de Cambra Florensa

Restorer of frames and paintings at LAB-ART (Barcelona)

BA in Philosophy and Letters (history with a specialization in archaeology)

*********************************

[1] When attempting to locate production centres geographically, it should be noted that frames have typically undergone changes in location over the years – perhaps many. They were often separated from their original paintings, regilded or painted or otherwise refinished to suit contemporary tastes, and, in many cases, stored in deplorable conditions. All these circumstances contribute to deterioration due to damage, destruction of the original surface finish and loss of context. As a result, there is often a lack of clarity regarding the origin of less-documented and -recognized patterns

[2] Timothy Newbery, Frames in the Robert Lehman Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2007, p. 260

[3] Silvered mecca frames are related to the popular Spanish Baroque style, as it was expressed from the 18th century; see María Pía Timón Tiemblo, El marco en España, 2002, Madrid

[4] ‘Italian and Spanish 17th century frames’, Picture Framing Magazine, October 2002

[5] Julien Lugand, L’ofici de daurador a Barcelona (1599-1834), 2024, Memoria Artium 33, Bellaterra, Barcelona, et.al., 2024

[6] Ibid.

[7] César Martinell, ‘El escultor Lluis Bonifás y Massó (1730-1786)’, Anales y Boletín de los Museos de Arte De Barcelona: Ayuntamiento, 1948

[8] Julien Lugand, op. cit., p. 180

[9] Albert Garcia Espuche, Una societat assetjada: Barcelona 1714-1713, 2014, Barcelona, p. 619

[10] Ibid., p. 620

[11] Ibid., p. 664

[12] Rosa Maria Creixell, ed., ‘Quadres, marcs i il·luminaries ‘, in Noblesa obliga. L’art de la casa a Barcelona (1730-1760), 2015

[13] Ibid.