Reframing Munch in the light of his original frames

An essay by Johanna Hänsch, translated by Iain Reynolds, ending with a half-hour film of the research and reframing process.

In tandem with the move of the Munch Museum into its new home on the Oslofjord, a large number of Edvard Munch’s works have been reframed: more than five hundred of them, in settings which are true to the original – authentic and faithful to the artist’s own designs – a fitting celebration of the opening of the new museum.

Munch (1863-1944), Self-portrait by the window, oil on canvas, c. 1940, Munch Museum, Oslo

After several delays due to the construction work and also to the pandemic, the Munch Museum finally opened in October 2021. Norway has dedicated a new building to its beloved, revered and celebrated painter in the new cultural district of Bjørvika, next to the opera and the national library; one which has been specially designed to display Munch’s art. It is five times larger than the old Munch Museum, with thirteen floors, eleven exhibition areas and a total of 26,000 square metres; this was very necessary, however, since the artist had bequeathed around 28,000 works of art to his home town.

Munch (1863-1944), The sun, 1910-11, o/c, 176.4 x 303.6 ins (450 x 772 cm.), Munch Museum

An extra gallery with double room-height was created for his monumental paintings, such as The sun of 1909, in order to present them appropriately. But not only the encompassing shell of the Museum – architecture, room climate and even safety standards – were custom-made for Munch’s work, but their more immediate surroundings as well: their frames. These were executed by the Munich firm of WERNER MURRER RAHMEN, led by Werner Murrer himself, who researched and studied Munch’s own ideas on framing and the contemporary presentation of his work. The results formed the foundation of the project: complex reconstructions of the original historical frames were designed and manufactured, and tailored frame by frame individually to each specific work.

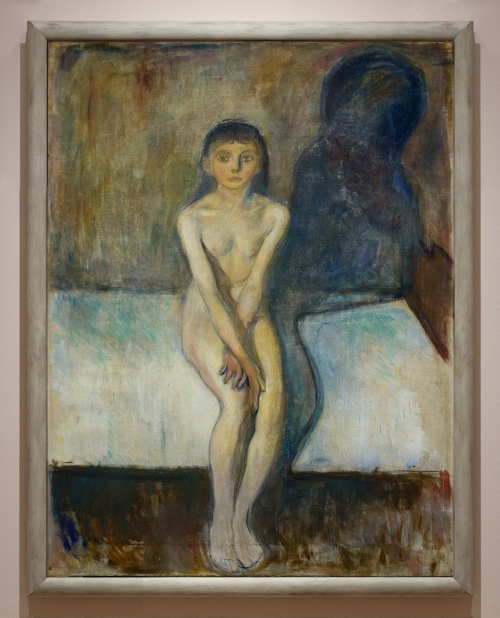

Munch (1863-1944), Puberty, 1894-95, o/c, 151.5 x 110 cm., Munch Museum

The five hundred reframings of paintings and graphic work completed so far include some of his most famous pictures, such as Puberty (1894/95), Madonna (1894), and one of the most famous images in art history – two versions of The scream, a chalk drawing of 1893 and a painting, of c.1910.

Munch (1863-1944), The scream, tempera & oil on cardboard, c.1910, Munch Museum

Munch (1863-1944), The scream, chalk on cardboard, 1893, and detail behind of the previous frame, Munch Museum

Corner details of new replica frames on the two versions of The scream, above; Munch Museum

Munch (1863-1944), The scream, lithograph, 1895, Munch Museum

With the black-&-white graphic version of 1895 there are actually three versions, all of which can currently be seen in the Infinite exhibition in the new Museum.

Munch (1863-1944), Self-portrait on the glass verandah, 1930-33, Munch Museum

Edvard Munch had very precise ideas abouthow his work should be framed. He preferred to use simple frames with a half-round torus profile, finished in white or brown; as he himself said,

‘A good picture can withstand a lot. Only bad pictures have to be completed with elegant heavy frames. I give them just a narrow moulding, preferably one that is convex and white’ [1].

Edvard Munch painting outside his studio at Ekely, photograph, Munch Museum

He also liked it when his frames were distressed by wind and weather. In his open-air studio in Ekely, he deliberately exposed both paintings and frames outside in order to make them look more organic, less new and untouched.

Munch (1863-1944), Death and the child, oil on canvas, 1899, Munch Museum

Munch (1863-1944), Elm Forest in spring, 1923-25, corner detail, Munch Museum

It was not just his avant-garde work which caused a storm of protest when it was exhibited, but also his frames. Munch consciously turned against the convention of splendidly decorated, gilded plaster frames which was fashionable at the time, preferring a minimal, unornamented design.

Corner details of frames with a convex torus profile and various finishes finish, WERNER MURRER RAHMEN

He is not only considered, therefore, as a pioneer of modern art, but also of Expressionist framing: the artists of Die Brücke modelled their own ideas upon his and developed them even further.

Munch (1863-1944), Self-portrait on a suitcase in his studio, Berlin, 1902, collodion print; exhibition: The experimental self, Munch Museum

Edvard Munch in his studio at Ekely on the outskirts of Oslo, c.1938, Munch Museum

Even before Werner Murrer Rahmen took part in the international tender for reframing works in the Munch Museum, the firm had an in-depth knowledge of Munch’s original frames. In its constantly growing image database (which contains more than 100,000 original picture frame combinations from every era), Munch’s own settings for his work are documented in detail. However, it is also important to examine actual examples of frames from the time when the works of art in question were created; so the firm has built up a comprehensive and unique collection of historical frames from the time of classical modernism in Munich. Because of this, there is a physical foundation for the theoretical knowledge involved. After the award five years ago of the contract for reframing Munch’s work, an important and very large new framing project, this research aspect of the project was intensified, and thousands of documents were examined.

Munch (1863-1944), Friedrich Nietzsche, oil and tempera on canvas , 1906, in previous frame, Munch Museum

Munch, Friedrich Nietzsche, 1906, reframed by WERNER MURRER RAHMEN; Munch Museum

The approach taken by Werner Murrer to the reframing of works of art (by both Old and Modern Masters) is based upon this meticulous art historical research. The goal is always an historically correct design. It was important not to restrict Munch’s work – to force it into an anachronistic corset – but to frame each piece according to the time when it was created. The artist was very much ahead of his time, and so the aim was to emphasize his modernity through a contemporary language of design. Taking into account all the historical sources, accurate hand-crafted reconstructions have been executed, based on original models for each individual work. A standard solution is never an option: every painting is examined individually to find the best and most appropriate solution.

Corner details of frames with a convex torus profile and white finish, WERNER MURRER RAHMEN

This applies not only to the profile, but to the whole frame, and the deliberately-induced aging of the finish. To make the frames look a hundred or so years old, special techniques have been developed to mimic the distress caused by time, so that it is hardly possible to distinguish between the replica and the original.

Munch (1863-1944), Starry night, 1922-24, Munch Museum

In order to create replica frames which are historically correct, but which also meet today’s strict requirements regarding conservation and safety, WERNER MURRER RAHMEN – in partnership with the company Halbe – has developed a technically highly complex system, consisting of an inner and an outer frame. Halbe manufactures the invisible inner frame, a protective ‘metal box’ in which the works of art are self-sufficient, and WMR creates the historical replica outer frame which will cover the latter.

Munch (1863-1944), Felix Auerbach, 1906, o/c, 85.4 x 77.1 cm., in original frame, Van Gogh Museum

Photograph of Munch’s 1906 portrait of Auerbach in its original frame, as exhibited in 1907 at the Cassirer Gallery, Berlin; Munch Museum

Photograph of Munch’s 1906 portrait of Auerbach in its original frame, as exhibited in 1907 at the Cassirer Gallery, Berlin; Munch Museum

The historical research which went into this project was extremely exciting; it included the discovery of original Munch frames posted on Instagram, for example – frames which no-one had previously paid any attention to – whilst the carving and finishing of the replica frames was, as always, a great pleasure. Seeing Munch’s works of art complete with their replacement frames in the new Munch Museum is probably one of the best moments in the three decades and more of WERNER MURRER RAHMEN’s history – and Edvard Munch himself would without doubt have been more than happy to see his work framed as he originally envisaged, and displayed in its spacious new home.

Johanna Hänsch, MA

********************************

New Frames for MUNCH, a film by Sebastian Eschenbach.

Film producer: Olivia Schubert

Collector and Jäger Filmproduktion GmbH

With many thanks to the team from Collector and Jäger for this documentary, and to TRU VUE, for realizing and sponsoring the film; with thanks to Werner Murrer for kindly allowing The Frame Blog to republish both film and article.

Munch (1863-1944), Summer night: The voice, 1896, o/c (unprimed), in previous frame (above), and new replica with detail (below), Munch Museum

********************************

[1] Stenersen, Rolf: Edvard Munch, Stockholm-Zurich 1950, p. 87