A flight of Christmas angels…

by The Frame Blog

…from various frames…

Sansovino frame with angels, doves and fruit, Private Collection

Angels have had a natural affinity with picture frames from the earliest period: at a point when the frames were still hardly more than raised, tray-like borders around the painted panels of which they were still part, angels began to cluster at the edges of the work like swallows about to migrate onto the summery continent of the moulding: for instance, on the Soest Altarpiece, c. 1240, in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (thanks to the wonders of the Google Art Project). In the stylized, church-like silhouette, the central dome, the rudimentary pinnacles and semi-hemispheres along the top are filled with painted angels – still a part of the lowered painting surface of the panel, but also separated from the main fields of action, in the process which would push them ever further outwards, as the principle image became more and more naturalistic.

Seventy years or so later, in Duccio’s small triptych of The Crucifixion, the Redeemer with Angels, Saints Nicholas and Gregory, 1311-18, the shape of the altarpiece has become even more like the section through a church. The wings of the two lateral panels open out like aisles alongside the nave, and the pedimented top rises up like the clerestory, to contain a painted Christ with supporting angels in a kind of celestial attic storey which lies somewhere between pictorial field and frame.

Giovanni Bellini, the Frari Triptych, 1488, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice

By the time that Giovanni Bellini painted his triptych of the Madonna and Child with saints in 1488, for the church of the Frari in Venice, the aedicular frame with its church-like silhouette had achieved an extraordinary degree of sophistication and refinement. This is an example of a major sculptural work created by a master craftsman, Jacopo da Faenza, whose artistry was of such a quality that – almost on equal terms with the artist, as so many of these carvers then were – he signed and dated this frame. It is a completely collaborative work; the structure rises from its altar like a small open chapel, the Madonna sitting in an illusionistic interior where the painted architecture continues seamlessly from the carved architecture of the frame: the painted capitals and entablature echoing the corresponding elements of the wooden façade.

Angels supporting a candlestick on the frame of the Frari Triptych (photo courtesy of www.museumplanet.com)

In its setting in a physical chapel in the Frari church, frequently quite dim during summer evenings and winter days, the altarpiece is illuminated by the large proportion of gilding relative to the area of the painted surface, which would have caught and reflected candlelight from the altar. In a delightfully bravura touch this is underlined by the four sculpted angels, two to each side, holding flaming candlesticks above the entablature to light up the celestial vision below.

Cima da Conegliano, Sacra conversazione, Gulbenkian Foundation

Angels are thus not only symbolic, with auxilary rôles supporting the main scene; they can also be immensely functional. Here, on a cassetta frame, a convocation of small angels supports the swagged cord dependent from the smiling mascaron at the top, ending at the bottom cartouche, and bearing at intervals a collection of festive bouquets, like artichokes.

Cima da Conegliano, Sacra conversazione, detail

These are adaptable angels, who will turn their hand to most religious subjects they are called upon to support, since what they are doing, in essence, is roping off the pictorial area in order to show its sacredness and its difference from the world of the spectator.

Two angels, carved in limewood, from the frame in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg, designed by Dürer for his Allerheiligendbild, 1511

More useful angels, here blowing trumpets to accompany a carved Last Judgment, have been sculpted on the cornice of the frame designed by Dürer for his Allerheiligendbild (Adoration of the Holy Trinity, or the Landauer Altar). The drawing of 1508 for painting and frame still exists [1], as does the frame – in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, unhappily sundered from the image itself, which is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Just as the Germanisches Nationalmuseum shows the frame on its website with a copy of Dürer’s painting, so the actual painting in Vienna has been set in a 19th century replica of Dürer’s frame, reproducing all the elements of the original – from the Last Judgment in the lunette of the pediment and the trumpeting angels, to the separation of sheep from goats on the frieze. This is a significant example of a work where the frame has been used to expand upon the painted image.

Copy of Albrecht Dürer, Allerheiligendbild, 1511, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, set into the original frame designed by Dürer, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg

The latter shows a vision of heaven, floating in clouds above the earth, with the saints, prophets, the blessed and all the angels adoring the Trinity. Without the frame it is a celestial world complete in itself: the frame provides the context of humanity, good and evil, and shows Christ as the link between temporal and spiritual worlds. This makes the separation of these interdependent pieces of one complete artwork all the more tragic, although the replica frame of the 1880s is a faithful substitute.

Working angels can have more pleasant rôles than grimly sounding the last trump. Here, two graceful, painted Raphaelesque figures in flowing garments like a Greek peplos fill almost the whole field of the frieze on a cassetta frame.

Painted cassetta frame, 17th century, all notes on which have unfortunately been lost: do you know where this frame is?

Standing on rather solid balls of cloud, they hold a jewelled crown between them above the top centre of what would have been the painting. This was presumably a picture of the Madonna, as the angels are carrying her attribute, white lilies, in their outer hands. Again, the frame is used as an auxiliary to the painted image: its frieze represents the realm of heaven, and the pictorial scene would have been one from the life of the Virgin on earth. This is emphasized by the narrow vista of landscape seen through the window-like cartouche, supported by two cherubs, on the bottom rail: the earth again, depicted as minute when seen from the viewpoint of heaven. The crown at the top indicates the eventual coronation in glory of the Madonna, and – deprived of its frame – the original painting would have represented only her human life and not its celestial apotheosis.

This use of a crown on a frame was adapted from religious to secular works, probably during the 17th century. The standard ceremonial manner of portraying a monarch came to be a three-quarter or (more often) a full-length portrait, often in coronation robes, but bare-headed: the crown would be carved in wood at the crest of the frame, as though the respective king or queen were being perpetually crowned in the presence of the spectators of the work. This was very useful for those royal portraits which were given as presents to favoured nobles, or as indications of authority to ambassadors travelling to distant locations to represent their country.

Crest of frame on Allan Ramsay and studio, King George III, c.1774, Firle Place, Sussex

These portraits were the outward sign that the ambassador represented his monarch – as though he actually took the king along with him. The ceremony with which the portrait was hung required a state canopy to be erected over it, and the ambassador to be seated before it, so that the crown would hover symbolically, metaphorically and in proxy over his own head. No angels are present on these frames, although they often appear in monarchical paintings, bearing branches of bays and laurels, and circling the particular sovereign’s head.

Veronese, Holy Family with Sts Barbara & John the Baptist, 1550, Galleria degli Uffizi

Baroque versions of the angels on the painted cassetta frame, above, can be found carved around the spectacular ‘Medici’ frame made for Veronese’s Holy Family with St Barbara. The painted angels were graceful late Renaissance adults, looking forward to the coronation of the Virgin in heaven, after her death. The ‘Medici’ angels are small cherubs, like the infant St John the Baptist in the painting; they look forward from the serene and happy group of the Madonna and Child, Joseph and the other two saints, to the horrors of Christ’s death; they gambol and hover amid the unfurling cartilaginous forms of the frame structure, but each of them holds one of the instruments associated with the crucifixion.

Veronese, Holy Family with Sts Barbara & John the Baptist, detail

Veronese, Holy Family with Sts Barbara & John the Baptist, detail

The ‘Medici’ frame is a version of the Auricular style, so-called because of the similarity of its fluid organic ornament to the interlocked curling forms of the human ear. It drew on various sources, including Mannerist architecture in Venice, marine decorations on grottoes, etc., in Florence, and the swirling, metamorphosing work of early 17th century goldsmiths, French, German and Netherlandish. All these ingredients seem to have come together through the presence of craftsmen of various nationalities at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II (1552-1612) in Prague; the court of Maximilian I of Munich was also important. The frame designs which emerged from this richly inventive stew are notable for the surreal manner in which the wood from which they are made is treated: its solidity and texture is subverted, so that it appears to melt and flow like molten gold. This can be seen in the flaring, folding substructure of the Veronese frame.

Veronese, Holy Family with Sts Barbara & John the Baptist, detail

Veronese, Holy Family with Sts Barbara & John the Baptist, detail

‘Medici’ frames are specifically those commissioned by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici during the last third of the 17th century, to frame the art collection he kept in his sumptuous apartment in the Pitti Palace, Florence. They hover between Mannerist and Baroque; exuberant, sculptural and curvaceous, often almost overpowering the paintings they surround. They are the work of master carvers, and are sculptures in their own right. Veronese’s Holy Family… is fortunately large enough and imposing enough to withstand the writhing, scrolling gilded setting which holds it like a vast jewel. And this particular frame is tailored to its contents, with its three-dimensional flying cherubs, holding nails, a hammer, pliers, a coil of rope, even Longinus’s lance. Like the next ‘frame’ in a strip cartoon, they foretell events of another time, taking the circle of Christ’s life from the infancy shown in the painting to His death on the cross.

Most angel frames, however, are not as active and participatory as this ‘Medici’ example. Often only the head of the angel, cupped in small wings like the sepal of a flower, blossoms on the corners and/or the centres of a frame, to denote the clusters of adoring cherubim which might have been, in other circumstances, gathered in the corners of the painting.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-94), Madonna and Child, Musée du Louvre

For example, on this beautifully carved cassetta frame, the wide flat frieze is completely filled by a ring of eight cherub’s heads with widespread wings, as though they were hovering in a jubilant circle around the Madonna and Child. Their wings merge around their necks into decorative ruffs, and the flight feathers spread across arabesque ornaments which spurt flames: so the angels may be intended to be fiery seraphim, although lacking the requisite six wings. The down-to-earth depiction (except for the haloes) of a mother and her child sitting in a sunny, book-filled room is thus turned by the frame into a recapitulation of the Nativity, with a soaring angelic choir.

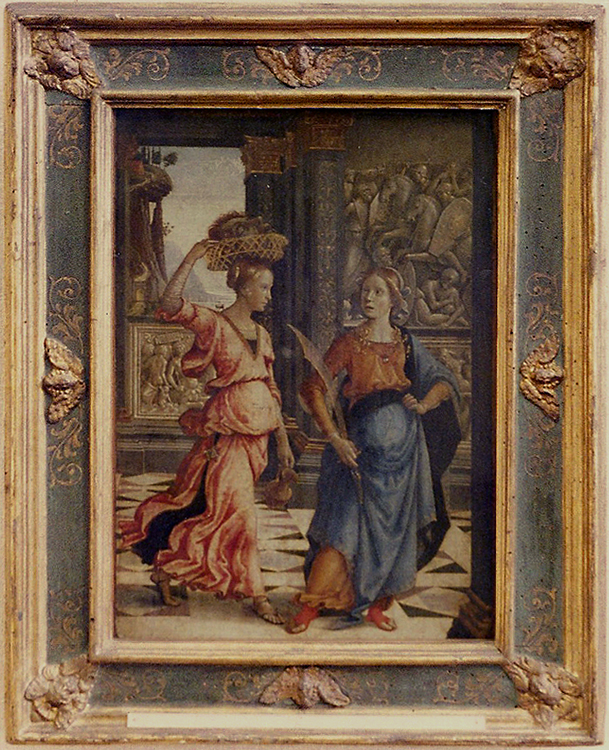

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Judith & her maidservant, 1489, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

This second Ghirlandaio has probably been reframed, since the story of Judith killing Holofernes (in the Old Testament Book of Judith) would not normally call down the flights of angels reserved for episodes and figures from the New Testament, or for God. Furthermore, the angels in the corners have six wings, indicating that they are definitely seraphim, the highest order of angel, and so only to be associated with God or with Christ. At the centres of the frame are cherubs with two wings, carved, like those in the corners; they are set on a painted tempera ground which was probably originally dark blue, and on which delicate fronds of scrolling foliage undulate and curl. This is a graphic representation of the sky, which turns the whole frame into an analogue of heaven; this, the seraphim and the upright format indicate that it may originally have contained an episode from the life of Christ, or perhaps a representation of the Trinity.

Andrea Previtali, Italian (Bergamask-Venetian School), fl.1502-d.1528, The Annunciation, c.1520-25; tempera on wood panel, Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, TN, Gift of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation 61.197

This Annunciation by Previtali has been reframed in a contemporary early 16th century parcel-gilt walnut frame of striking design. The frieze is completely filled with an elaboration of a guilloche ornament, multiplied into an intricate braid of dark walnut and gilded ribbons (the walnut would originally have been lighter in tone). This terminates at the corners in parcel-gilt acanthus leaves, whilst four cherubs’ heads are set at the centres. Interestingly, where many heads face either into the painting or (less usually) away from it, here the three top and lateral heads face inwards, and the bottom one outwards: thus none of them is upside-down.

Andrea Previtali, The Annunciation, detail

The heads are also parcel-gilt, with golden curls, inscrutable dark faces and powerfully-feathered wings. Small and discreet, they preside over the shimmering river of light and movement created by the carved braiding of the frieze; the result is opulence restrained by geometrical patterning.

Castilian School, The Adoration of the Christ Child, art market 2004

Another frame with no upside-down angels is this sculptural late Renaissance Italian cassetta, which now contains a Castilian Adoration of the Christ Child. The long, elegant Gothic lines still current in the Spanish painting are rather at odds with the naturalistically chubby and plastic infant angels of the frame, with their fanned-out wings drawn at the bottom into fringed collars. These angels are invoking symbols again: sprays of vine leaves and grapes surround them, and they are separated by scrolling foliate branches from which depend apples, pears and figs. The apple stands for the Fall of Man, which Christ came to redeem, the pear for Christ’s love for mankind, and the fig for both the Fall and for fertility. The grapes refer to the sacrament of the Eucharist, when the wine becomes the blood of Christ. The frame in this way sets out a schematic map of man’s relationship with God, from the Fall and loss of Eden, through man’s redemption by Christ in the crucifixion, and on into the contemporary, ‘modern’ celebration of the sacrament of the Eucharist at mass.

Castilian School, The Adoration of the Christ Child, detail

Looking at one of the angel’s heads close up, we can see both the realism of depiction, and the details of technique. The background of the frieze has been covered in fine punchwork, giving texture through a granular matte finish which contrasts with and highlights the smooth and gleaming surface of the sculptured motifs. The latter are carved in high relief with a little undercutting, enhancing the illusion of a body in the round by increasing the contrast of light and shade which models the angels’ faces.

Venetian or Northern Italian school, St Sebastian, 1512-31, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

This St Sebastian has been reframed in a much later pattern – an Italian cassetta more Baroque in style than the Renaissance frames above, and dating from the first half of the 17th century. It has deeper, more ample mouldings, Mannerist cartouches on the centres of the frieze, and large seraphim heads clasped in a leaf-like nest of wings which overflow the picture surface. The prominence of these heads sets up a typical Baroque grid of imaginary lines between them, drawing invisible diagonals across the painting. In a work of the same period, this web of lines would echo and enhance the compositional lines of the picture, emphasizing the head of a figure, following the dramatic pose of leg or arm, picking out salient objects. In the static Renaissance composition of this St Sebastian, all upright and horizontal lines, the dynamic of the frame collides with that of the painting, and the large angels’ heads overpower the saint, perhaps explaining why he looks so discomforted.

Titian, Madonna & Child with Saints Joachim, Joseph and John the Baptist, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

The frame of Titian’s Madonna and Child with Saints is very different in profile from the flat, tray-like section of a cassetta frame. The main moulding here is a carved torus of fruit and foliage, imitating the round (tondo) frames like garlands which border late 15th and early 16th century glazed terracotta plaques by the Della Robbia family.

These terracottas, with their colourful and fruitful wreaths, are at once very naturalistic and highly symbolic: the leaves, flowers, pomegranates, lemons and figs are realistically modelled and painted, yet at the same time they denote virtues and qualities. The Titian frame is more cursorily carved, but it draws on the same designs, and the same symbolic language. It is contemporary with the painting, and may even be the original setting; it seems to contain stylized pomegranates (for the Resurrection), apricots (for encouragement; the attribute of the Holy Spirit); and figs (fertility and the Fall). The carved garland is bordered by four orders of ornament, giving a dense band of rich decoration over which the light flickers and moves, catching the top surfaces in a constant shimmer of movement.

Titian, Madonna & Child with Saints Joachim, Joseph and John the Baptist, detail

And on top of the garland four angel heads perch like butterflies poised for flight, their wings apparently sprouting from behind their ears and their necks hidden in a thick ruff of feathers. They seem entirely unintegrated with the rest of the design, settled temporarily on the carved leaves and fruit, all facing forward, their wings beating for takeoff. They may be about to tow the frame, with its unconscious and serene Holy Family, out of the dangerous temporal setting of the gallery and into a calmer metaphysical zone.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Mary, Lady Guildford, 1527, St Louis Art Museum

Finally: a Renaissance cushion frame, with a convex frieze and vestigial mouldings at top and bottom (a salute to the aedicular altarpiece structure with entablature and pedestal), which has been hijacked from sacred to temporal use. Originally it would, again, probably have held a Madonna and Child; now it holds a portrait of the second wife, Mary Wotton, of Sir Richard Guildford, comptroller of the household of Henry VIII. Mary is at least a pious occupant, with her prayer book and rosary. Although she looks suitably matronly for her cuckoo-like appropriation of this frame, she was only twenty-seven when the portrait was painted, and had no children by Sir Richard.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Mary, Lady Guildford, detail

Seven cherubs colonize the frieze; the lateral pair has been cleverly adapted to the long sides of the frames by raising their wings vertically behind their heads, so that they can remain the right way up; their collars of feathers now look like Elizabethan ruffs. Their faces seem to show evidence of paint on top of the gilding (possibly later?); they are pink-cheeked and chubby, with crinkled curls and almond eyes, like small Tudor choirboys. The eighth cherub, on the bottom rail, has been supplanted by a cartouche, which would probably have held the coat of arms of the donor (if the work had been given to a church), or of the owner (if a domestic altarpiece). The current pairing of portrait and frame illustrates the constant movement of frames through the ages, as the original setting is discarded, because of changing fashions, or because a new owner wishes to imprint his ownership on his possessions. Luckily, these angels have found a suitably religious and beautifully-painted occupant to temper their loss.

Detail of angels on a frame now on an El Greco

Happy Christmas!

All images included here are courtesy of the respective museums, save for those who haven’t responded to my emails. Most of the photos are courtesy of Paul Mitchell and the Paul Mitchell Archive, to whom I am extremely grateful. I am also especially grateful to Marilyn Masler, Associate Registrar of Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, for the splendid image of Andrea Previtali’s Annunciation in its frame; also to www.museumplanet.com. Thank you to all those curators who have expressed support for, and interest in, this project.

[1] For drawing: open, and scroll down to Plate 6, p.6:

http://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/3%20Durer%20and%20Sculpture.pdf

Thank you !

LikeLike

Thank you, too… 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you, Lynn! It is a great article! Thank you also for The Frame Blog and for all your work on bringing a public attention to an existence of integrity between paintings and their frames!

Margaret

LikeLike

Hi, Margaret – It’s so nice to hear from you, and thank you for such kind comments: I do appreciate them. Now – all I have to ask is: will you (very kindly) write an article for me on your current pet frame interest, please?

Lynn

LikeLike

What a wonderful special holiday edition! Thank you, Lynn!

LikeLike

Dear Sue – Thank you for such a nice comment.. and how lovely to hear from you! Hope that you might write something for me, perhaps, if you have time? Have a terrific Christmas –

Lynn

LikeLike

Beautiful angels on the frames! Lynn, thank you very much for this gift!

LikeLike

Dear Oksana – How lovely to hear from you, and thank you for such a nice comment! Have a very happy Christmas –

Lynn

LikeLike