Wilhelm von Bode: framing the Old Masters in Berlin

by The Frame Blog

Wilhelm von Bode (1845-1929) became the first curator of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (now the Bode Museum) in Berlin, having previously directed the Gemäldegalerie and later the associated complex of museums, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. He reinvigorated and enlarged their collections, enabling Berlin to overtake Munich and Dresden as the centre of historic and 19th century art in Germany. He was also greatly interested in the framing and presentation of the art in his care, and in 1912 wrote the essay which is republished here, translated by Peter Schade.

*

Introduction by Peter Schade, Head of Framing, National Gallery, London

Bode wrote this article on the framing of Old Masters for a quarterly publication aimed at the supporters of the Gallery. It stands out – still – as the most sensible text ever written about framing, especially the framing of a museum collection. Almost every observation rings true today, and the hundred years which have passed have added almost no additional or superior insight into the problem. We still have to challenge the perceived value of historical settings, however ill-conceived and inappropriate they might be for the artwork they surround. Few people have articulated the question of how to frame paintings with Bode’s connoisseurship, knowledge and practical experience. I came across this text in 2009, five years after I had started work as the Head of Framing at the National Gallery. I very much hope that the work we have done over the last fourteen years follows to some degree the example set by Bode.

It is remarkable how many of the framings which he singles out in the text have survived the turbulent history of the last century. The most tragic case is that of the Fra Bartolomeo altarpiece, the only painting for which Bode managed to acquire the actual original frame, a century after it was sold unframed to Edward Solly. This frame survived the war, because it was left in the store of the museum, while the painting was put into what was thought to be safe storage in the Flakturm Friedrichshein, where it was burned along with many other large altarpieces.

*

Wilhelm Bode, ‘Reframing the paintings in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum with antique frames’, translated by Peter Schade. Originally published in Amtliche Berichte Aus Den Konigl. Kunstsammlungen, XXXIII. Jahrgang, Nr.9, June 1912, Berlin

Since paintings were first collected and displayed in purpose-built galleries, in the age of Philippe II of Spain and the first grand Dukes of Tuscany, the aim of the aristocratic collector has been to harmonize his collection by framing his paintings uniformly.

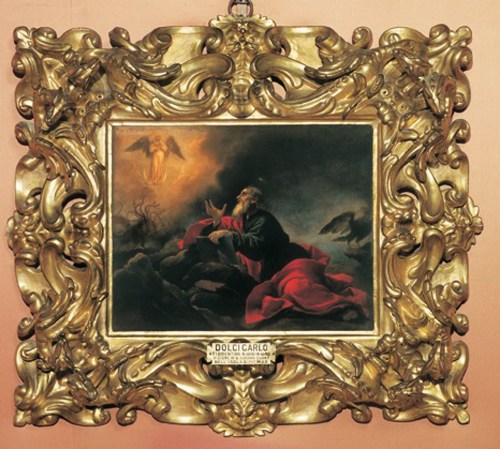

Carlo Dolci (1616-88), St John on Patmos, oil on copper, 38 x 49 cm., frame 73 x 87 cm., Galleria Palatina, Florence, in ‘Medici’ frame

The pictures in the Palazzo Pitti, for instance, have – almost without exception – the characteristic Baroque setting known as the ‘Pitti’ frame [1].

Frans Snyders (1579-1657), Still life with woman & a parrot, 1625-50, o/c, 60.6 x 93.3 ins (154 x 237cm .), Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, in Dresden Rococo gallery frame

Around a hundred years later in Dresden a much lighter giltwood frame was developed, probably based on the experience of a dealer such as Erzherzog Leopold Wilhelm in his Brussels gallery, where heavily-carved and gilded frames could lift a particular painting, but lessened the effect of the gallery as a whole. The same happened again a century later when the collection in Berlin was first displayed in Schinkel’s new building.

Davide (1452-1525) & Domenico (1449-94) Ghirlandaio, Madonna & Child enthroned with saints, c.1480, 172 x 212 cm., Gemälgalerie, Berlin, in NeoClassical Schinkel frame with palmetto ornament

All the paintings, about eleven hundred in total, were set in gilded frames of Schinkel’s design. The hundred years which had elapsed since the creation of the uniform gallery frame in Dresden are painfully apparent in the Berlin gallery frame. The designer (Schinkel) and the framemakers have produced a pattern which, in profile, finish and construction, demonstrates almost incomprehensibly poor taste, and appear structurally very flimsy. The Schinkel frame is based on a shapeless wave or ogee profile, which was supposed to gain emphasis through combining a concave and convex moulding; although in reality the intention is completely lost. The ornament is formed of metal palmettos applied at the corners and sometimes also at the sides, and the whole frame is gilded with a matt bronze-like finish.

Bastiano Mainardi (c.1460-1513), Madonna & Child with John the Baptist and three angels, Gemälgalerie, Berlin, in Schinkel frame with matching paterae in the spandrels

All antique frames were removed, and the paintings put into this livery frame, apart from a few more important works, where the design was embellished with epaulettes and stringing. Remarkably, during a period of austerity, 180,000 marks were spent on this project. Only latterly have we come very slowly to understand that each painting can only truly be seen to its best advantage framed in the original style of its period and place. We have also observed that the resulting variety does not diminish the display in the rooms of the Gallery, but – because each hang is arranged by grouping works of the same schools – the frames relate to each other harmoniously.

Raphael (1483-1520), The Ansidei Madonna, 1505, o/panel, 216.8 x 147.6 cm., National Gallery, London; acq. 1885, frame by Reginald Dolman, based on a Venetian church door by Pietro Lombardo

The National Gallery in London was the first to implement this modern scheme, even if only to a limited extent: for example, aedicular frames were commissioned for the fabulous large 16th century altarpieces which the Gallery had acquired in the 1860s. But it was left at that; besides which, the choice of models for these replicas and the quality of the execution were both indifferent. When Julius Meyer, and I as his assistant, were given charge of the Berlin Gallery forty years ago, we immediately tried to improve the frames – at least of the most important paintings. We, like the directors of the National Gallery, started by commissioning suitable reproduction frames, because antique frames were almost impossible to source. It soon became apparent that contemporary framemakers, even the most highly skilled craftsmen from Italy and France, were and still are unable to carve and gild with the necessary expertise to produce frames which look right with the paintings; even the copies of Dutch ebony moulding frames were too uniformly black and too highly polished. We gradually managed to replace these reproductions with good antique frames, which were acquired with lesser paintings or had been used to frame copies of the original paintings; these frames were often cheaper than the replicas. I asked the dealers to buy similar fine antique frames for us. As a result we were offered more, but they also became more expensive – recently up to ten times as much – because nowadays every collector wants to frame his valuable paintings in beautiful antique frames, often trying to match the period and the original location of the work.

After almost thirty years of striving to reframe the paintings of the Christian epoch in antique frames of the same period, or more seldom in copies, we now have only a small number of the earlier Schinkel frames or other unsuitable newer frames left. And because of the low prices which were asked for antique frames in the beginning, as well as support from friends of the museum, the overall acquisition costs were only about a fifth the cost of the Schinkel frames.

We found early Italian frames most easily, especially in the beginning, and took advantage of these opportunities as much as possible. The intention of a great master can only be achieved in the context of the original frame, because in most cases the artist would have been involved in toning the gold, or in painting the frame to harmonize with the picture or painted sculpture. Paintings have only seldom retained their original frames: they are only found in larger numbers on smaller gothic paintings, where the gilded mouldings are often bound to the panel or made out of the same piece of wood.

Jan (c.1390-1441) & Hubert (c.1366-1426) van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece, c.1430-32, o/oak panels, 136.8 x 181.2 ins overall (350 x 461 m.), in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, from 1820-1920; now in St Bavo Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium; architrave frames with butt joints

The same also occurs on simple Renaissance aedicules. Even Schinkel’s framing fury had to refrain from removing these frames, so they were brought in line by regilding them, or were hidden inside the Schinkel frame. This, for instance, was the case with the panels of the Ghent altarpiece, which have now been freed from their masking Schinkel mouldings and are all on view in their original frames.

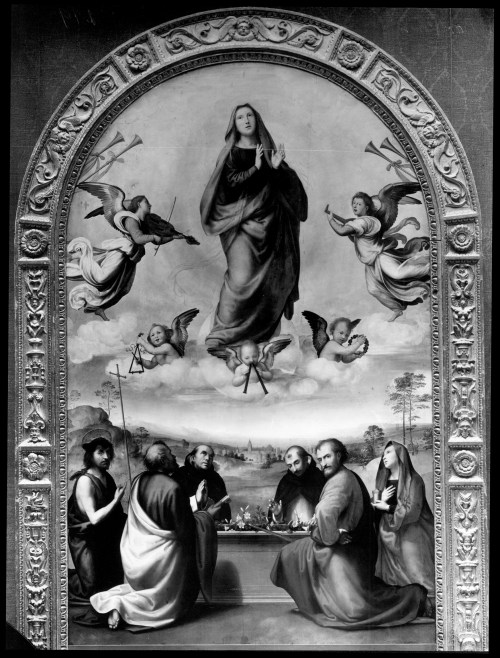

Although we have bought antique frames, we have probably never achieved our greatest desire, to discover an identical design to the frame that the artist had intended. And only in very exceptional circumstances was it possible to find the original frame of a painting; for example, we did manage to acquire the original setting for Fra Bartolommeo’s large altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin.

Fra Bartolommeo , The Assumption of the Virgin, c.1507-08, o/poplar panel, 301 x195 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; detail in 16th century Mannerist frame. Photo: Francine & Sterling Clark Institute

The frame remained in Pistoia when Edward Solly bought the altarpiece over a hundred years ago, and a painted copy was put in its place. The frame was later sold when the poor copy was replaced by a modern picture, and, by a lucky chance, I was able to identify it as the original and present it to our panel [2].

Raphael (1483-1520), Colonna Madonna, c.1507-08, o/panel, 52 x 38 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; contemporary parcel-gilt cassetta, the frieze carved with a vertebrate grapevine & grapes

We also know the whereabouts of the original polychrome aedicular frame of Raphael’s Colonna Madonna, but unfortunately the owner of the frame is convinced that the old copy of our painting inside the frame is the original and he won’t sell the frame without it.

Since original frames can only be rediscovered by the most unlikely coincidence, our task is to find replacements which are appropriate in every way for the painting – and not just in size, of course; the frame must first of all be of the right period and nationality, and it must harmonize with the painting in its profile and proportions, colour, and tone of gilding. It must complete the picture and intensify its intended effect. In the first instance, works remaining in their original locations should be carefully studied (fortunately there are examples of these for almost every school of painting), in order to obtain a thorough understanding of frame designs and their employment for specific subjects. When all these considerations are borne in mind, it should be possible to acquire or to reproduce frames so successfully that they will be taken for the originals.

Raphael (1483-1520), Madonna Terranuova, c.1505, o/poplar panel, 88.5 cm. diam., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; replica early 20th century tondo frame with fruit & foliate garland springing from bound urns at the base to a rose at top centre

Raphael (1483-1520), Madonna & Child with saints, 1502, o/panel, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; tabernacle frame with donor shield in the apron

Within our own collection, this effect seems to me almost completely realized in, for example, the carved tondo frame on Raphael’s Madonna Terranuova and the tabernacle on his small Madonna & Child with saints (both above). It is also true of the aedicule on a tiny Bonfigli Altarpiece, the large polychrome altarpiece frame on a Raffaellino del Garbo, many of the Florentine 15th century stucco and terracotta relief sculptures, and the coloured tondo frame on Donatello’s small bronze Madonna , amongst others. For many of the portraits by Bronzino and his peers we were able to acquire the characteristic parcel-gilt (lumeggiate in oro) Florentine walnut frames.

Giorgione (1477/78-1510, Portrait of young man (‘The Giustiniani portrait’), o/c, 22 3/5 x 17 9/10 ins (57.5 x 45.5 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; cassetta with carved undulating vine, flower, cosse-de-pois and bird decoration, flowing from top to bottom centre on a blue ground

For Giorgione’s portrait we bought an almost exactly contemporary polychrome Venetian frame, which is similar to Giorgione’s only existing original frame on a beautiful portrait in a private American collection (as yet unpublished).

Alessandro Allori (1535-1607), Portrait of a young man, o/poplar panel, Bode Museum, Berlin; black and gold ‘Sansovino’ frame, symmetrical about both axes

For portraits by Titian we obtained 16th century Venetian frames with characteristic garlands of fruit and flowers; and for paintings by Tintoretto and Sansovino’s polychrome stucco Madonnas, the contemporary Venetian Baroque design now known as a ‘Sansovino’ frame (above).

G.B. Tiepolo (1696-1770), Rinaldo & Armida and Rinaldo’s departure from Armida, 1755-60, both o/c, 15.3 x 24.4 ins (39 x 62 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Canaletto (1697-1768), Santa Maria della Salute, pre-1730, o/c, 17.3 x 35 ins (44 x 89 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

All three in Venetian panel frames with shallow relief floral rinceaux on a textured ground and shaped reposes

Until recently we were also easily able to buy refined classical frames for Baroque Bolognese and Roman works, as well as good quality 18th century Venetian panel frames for paintings by Guardi, Tiepolo and Canaletto.

Bartolome Esteban Murillo (1618-82), The baptism of Christ, c.1655, o/c, 91.8 x 63 ins (233.2 x 160.1 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; detail of Spanish frame with running gem ornament at sight edge, and leaf & scrolling flower corners & centres

Spanish Old Masters are almost never found in their original frames, but painted interiors by Velázquez, Carreño and others reveal that royal palaces were furnished with simple black frames with gilded Baroque corner-&-centre ornaments, similar to those made in Italy, possibly under Spanish influence. We framed most of our Spanish paintings in this kind of dynamic pattern (apart from paintings of the 16th and 17th century, which were put into lighter giltwood frames).

Nicolas de Largillierre (1656-1746), The sculptor René Frémin, c.1713, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; in French late Régence frame with scrolling foliate and shell corners & centres, cosse-de-pois & roses-à-tiges in ogee; sanded frieze

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-88), The Marsham children, 1787, o/c, 95.6 x 71.6 ins (243 x 182 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; acq. 1982, but representative of 18th century British style for Bode: NeoClassical frame with leaf-bound fasces on the top edge, and centred pendant garland of moulded bell-flowers in the frieze

The French and English paintings more frequently retain their original frames: that is, the frames given to the paintings by 18th century collectors. In Germany Fredrick the Great was very interested in fine frames, even demanding that they should be designed to intensify the mood of the painting. Frames at this period were made in the Rococo style, which led to some very curious miscegenation – particularly for earliy Italian and Netherlandish paintings, as some examples in the royal palaces demonstrate. They are just as much at odds with the character of these works as, for example, Chodowiecki’s late 18th century illustrations to Shakespeare’s plays.

Framing paintings of the German and Netherlandish schools is far more difficult than sourcing antique frames for these works. Paintings from the 15th and early 16th century have only retained their original frames where the mouldings are carved from the same piece of wood as the painted panel, or else pinned and glued to it, as for instance is the case with the panels of the Ghent altarpiece.

Hans Süss von Kulmbach (d.1522), Adoration of the Magi, 1511, o/panel, 60.2 x 43.3 ins (153 x 110 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; rainsill frame with Gothic branch and spiralling acanthus ornament on a blue ground

Individual frames of this kind are almost never available for sale. Finding a small Gothic frame that was the right size for our early-Netherlandish Martyrdom of St Sebastian, or an antique altarpiece frame for Kulmbach’s Adoration of the Magi: these were rare accidents. It is thus necessary to copy antique models, or to use suitable frames from other schools where antique examples are not obtainable. Only reproduction frames for early northern mediaeval paintings can be used, since appropriate antique frames cannot be found in other schools. The original moulding frames used for many German and Netherlandish paintings until the first decades of the 16th century are relatively easily copied, but painted finishes which were specifically toned to harmonize with the image are more problematic, and almost impossible for the copyist to get right. This is particularly difficult in the case of work by the Van Eycks and their followers; their frames were frequently painted with faux stone finishes which were matched with sophisticated expertise to the tone and hue of the paintings.

Jan van Eyck (c.1390-1400-41), Baudouin de Lannoy, c.1436-38, o/oak panel, 10.2 x 7.6 ins (26 x 19.5 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; cut down cassetta with undulating foliate sgraffito ornament in frieze

We have therefore tried to find contemporary Italian frames in relatively dark tones for these paintings, and also for later northern works of the early 16th century, which they suit particularly well. The latter patterns are mainly Florentine walnut frames, plain or parcel-gilt, and, less often, Venetian frames with sgraffito or mordant gilding against dark blue or black.

Christoph Amberger (Augsburg, c.1505-61/62), The cosmographer Sebastian Münster, c.1552, o/limewood, 21.9 x 17 ins (55.8 x 43.3 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; cut down cassetta with dripped pastiglia corner-&-centre ornament on a red marbled ground

Anthonis Mor (1519-75), Duchess Margarete of Parma, c.1562, o/c, 41.7 x 29.9 ins (106 x 76 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; parcel-gilt black-painted frame with undulating sgraffito vine in frieze

This has, in my opinion, yielded very good results: for instance, the Venetian frame with a red ground on Holbein’s portrait from the Millais collection[3], the black frame with gold ornament on the Portrait of Margarete of Parma, or the Florentine walnut frame on the large female portrait by Joos van Cleef.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), Young Venetian woman, c.1506, o/poplar panel, 11.2 x 8.4 ins (28.5 x 21.5 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; parcel-gilt and polychrome cassetta with Islamic leaf ornament on top & sight edge, with scrolling foliate decoration, birds, beasts, flowers and suns, in frieze

Even the wide Venetian frame, above, with its finely-detailed gilt and polychrome decoration on a black lacquered ground, enhances our Dürer. This Portrait of a young Venetian woman – an unusual work by the artist – is considerably improved by its frame, although the latter was made about a century later than the painting.

I hope that eventually all the pictures of this school will be framed more in keeping with their character, even if the problems of tracking down and affording appropriate settings will continue to increase.

Discovering antique Dutch and Flemish frames, or locating suitable original models to copy, should – you would think – be relatively easy. They are the same period as the 17th century French and Italian frames which, until recently, were fairly plentiful; and most of the paintings are cabinet pieces which were collected in their thousands during the 18th century, right across Europe, and must at first have been acquired in their original frames. However, the case is almost the opposite; apart from the simplest black profiles, it is almost impossible to find such frames. As far as I know, not one of Rembrandt’s or Rubens’s works is framed as it would have left the artist – or even in a contemporary style – apart from Rubens’s large-scale altarpieces in the churches of Belgium.

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Return of the Holy Family, 1624, Church of St Charles Borromeo, Antwerp; returned in 2012 to its original altarpiece frame after 140 years in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum, New York

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), The miracle of St Ignatius Loyola, c.1617-18, painted for the Church of St Charles Borromeo, Antwerp; now Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, in a Baroque parcel-gilt frame: compare this with the companion altarpiece returned to its position in the church, above

It is impossible to reproduce these large Baroque settings in the context of a museum, as can be seen in the case of Rubens’s altarpieces from the church of St Charles Borromeo, Antwerp, two of which are now in the Wiener Hofmuseum [4]. Such large paintings can only support contemporary, elaborate altarpiece settings when they are placed on the axis of a large room, where they can also be seen from a distance in an enfilade.

Alvise Vivarini (c.1446-1503-05), Pentecost Altarpiece, c.1478, o/panel, Bode Museum, Berlin

We have framed two large early Italian altarpieces by Alvise Vivarini and Cosimo Tura in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in this way, but one feels that, even with these meticulously reproduced frames, neither the carver nor the gilder understood how to channel the spirit of the old masters in their technique.

Rembrandt (1606-69), John the Baptist preaching, c.1634-35, o/c on panel, 62.7 x 82.1 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Rembrandt (1606-69), drawing of John the Baptist preaching shown in frame, c. 1655, pen & wash, 14.5 x 20.4 cm., Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des arts graphiques, L. Bonnat Bequest (Ben.969)

Rembrandt (1606-69), The Holy Family, 1646, Kassel, Museumslandschaft Hessen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Photo: courtesy Rijksmuseum

Nicolaes Maes (1634-93), after Rembrandt, The Holy Family with Joseph cutting wood, 1646-50, coloured chalk & wash on vellum on washed mount, image 22.8 x 27.9 cm., Ashmolean Museum

There is a Rembrandt drawing of a frame, now in the collection of the Louvre, for the painting of John the Baptist preaching in the Gemäldegalerie; and a very similar frame was created by the artist as an integral setting of The Holy Family, in the museum in Kassel [5]. However, such a monumental structure was clearly designed for a particular setting, and would be quite unsuitable for a gallery.

The common type of border for panel paintings in the Spanish Netherlands was a black moulding frame (apart from altarpiece settings, or decorative pictures set into panelled walls, with a tapestry-like effect). Like the Interior of a Gothic church by an unknown Antwerp artist of 1620 in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm [6], even large and important works by Rubens were given simple black mouldings, which were probably chosen in the place of a gilded frame so that they would stand out against rich golden tapestries. The designs of giltwood frames (in the few cases where the originals survive on Flemish cabinet pictures) derive first from Italian sources and later on from French Louis XIV models.

Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625) & Hendrick van Balen (1575-1632), Madonna & Child in a garland of flowers, 1608, o/ panel, 27 x 22 cm., Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan; cassetta with scrolling foliate sgraffito ornament in a painted brown frieze

Fine Renaissance-style Italianate frames with arabesque gold ornament on a brown ground have survived on, for instance, Jan Brueghel’s paintings in the Ambrosiana, Milan, commissioned by Carlo Borromeo. Black moulding frames were also prevalent in Holland with more or less ornamented profiles; the earlier ones were made from painted oak, and the later versions more often from polished ebony.

In the Netherlands at that point, giltwood frames in Auricular designs were considered more aristocratic, and were also much more expensive. They were chosen for the more ostentatious images: for overmantel paintings, for favoured family portraits, or for particularly valuable cabinet pieces.

Emanuel de Witte (1617-92), Interior of the Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, c.1680, o/c, 85.2 x 69 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; acq. 1874; in Auricular frame

The profile and decoration of these frames – which were in fashion from the mid- to late 17th century – were of a very particular design: naturalistic flowers or bunches of fruit carved on a broad flat base. Sometimes different motifs were used, in particular a distinctive scrolling, melting ornament inspired by the designs of Jan Lutma the goldsmith, and called after him the ‘Lutma’ frame. This pattern is a metamorphosing confection of segmental shapes, scrolls, marine forms and birds’ heads, which are almost unrecognizable en masse, seeming to dissolve under the gaze as if into the waves of the sea. The Auricular style, the origins of which are in the Venetian ‘Sansovino’ frame and in early 17th century northern designs, is – besides in the work of goldsmiths – developed most expressively in the creation of picture frames. These frames were not only gilded and toned to harmonize with a particular painting, they were often designed especially for that image. Flower and fruit still life paintings were framed with carved flower and fruit ornaments, portrait frames were decorated with motifs related to the occupation of the sitter (military trophies for officers, musical instruments for musicians and music lovers, etc). Similar emblems are also sometimes found on the settings of genre pictures by Mieris, Dou and others. Original frames of this kind are rare and hardly ever appear on the market. In spite of great efforts, I have still only managed to buy half a dozen of them over several decades, and could often only obtain them on paintings of minor importance, which then had to be accommodated somewhere in the system.

Cornelis Bisschop (? 1630-74), Interior with a jacket on a chair, o/c, 45.2 x 37.8 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, with a plain moulding frame top left, and an Auricular frame on the main wall

Finding the right painting for such a frame is equally difficult, since they are impossible to adapt in size, and the decoration – as mentioned before – tends to be very specific to the subject. For this reason they can only rarely be copied successfully. Auricular frames which appear in interiors by Steen, Metsu, Vermeer and others cannot be used as models because their depiction is never sufficiently clear (above), while engraved designs of cartouches and borders are not suitable to be reproduced as picture frames.

Gabriel Metsu (1629-67), Jan Jacobsz Hinlopen & his family, c.1662, o/c, 28.3 x 31.1 ins (72 x 79 cm.), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; reverse ebony moulding frame

We have therefore used a number of antique ebony frames (mostly with a single gilded moulding: frames with several – although popular in Holland – proved too distracting in the gallery) for Dutch pictures of the early 17th century, or we have had copies made. These black frames, especially the copies, do tend to look very uniform and dull in large numbers, and we have therefore retained some of the older Baroque and Régence frames in which these pictures are often found – especially those coming from private British collections.

Rembrandt (1606-69), Samson threatening his father-in-law, 1635, o/c, 62.4 x 51.3 ins (158.5 x 130.5 cm.), Gemäldegalerie Berlin; 17th century British panel frame, with shallow relief panels of floral sprigs and shaped reposes

The black frames, which were often an economic choice, were generally removed when the paintings were integrated into French and English collections, and put into Baroque frames suitable to the respective interiors. These frames tend – even when they are a few decades, or even a century, different in period from the paintings – to harmonize well with them. French Baroque frames became fashionable towards the end of the 17th century throughout the Netherlands, and we have a number of original frames in that style on paintings bequeathed by the Princess of Orange. We have also improved the look of the gallery with acquisitions of good quality French frames, for which one would now have to pay 5000 francs or more in Paris. These new frames – on Rubens’s St Cecilia [7], Van Dyck’s Lamentation of Christ [8], Rembrandt’s Ansolo [9], his Hendrickje [10] and Daniel [11], and on Jan Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch, and others amongst our Dutch masterpieces (now freed from the tedious frames of the last century) – have enhanced both the individual paintings and the entire collection. Apart from using these valuable French frames, we have also framed our Netherlandish paintings in fine late 17th–early 18th century British and Venetian frames, in a style which used to be mistaken for French.

We have not yet finished remodelling our Gallery; we still have a number of paintings to tackle, including some large altarpieces which are still in Schinkel or other 19th century frames, for which we have not yet found suitable antique replacements. Some paintings and relief sculptures have also been furnished provisionally with antique settings which are better than their former frames, but not quite the ideal solution. There is still work to be done, things to be improved, and new acquisitions which often require suitable frames. To deal with this ever more difficult and costly task we have been amassing a rich stock of good antique frames, which we aim to increase periodically.

Bode

Donatello (attrib.; c.1386-1466), Madonna & Child with five angels, c. 1445/50, terracotta relief in contemporary classicizing Roman-style giltwood aedicule, Bode Museum, Berlin

************************************

Peter Schade is Head of Framing at the National Gallery London since 2005, where he has been responsible for the reframing of about 270 paintings in the permanent collection.

Originally from Berlin where he trained as a woodcarver, Peter has been working almost exclusively with antique picture frames since he came to London in 1990. He has documented his work for the National Gallery in articles published in the Annual Review from 2007/08 onwards.

Highlights of his work include the frames for the following paintings, amongst many others:

Leonardo, The Virgin of the Rocks (NG1093)

Moroni, Portrait of a gentleman (NG2094)

Palma Vecchio, Portrait of a poet (NG636)

Titian, Allegory of Prudence (NG6376)

Rembrandt, A woman bathing (NG54)

Sebastiano, The raising of Lazarus (NG1)

Degas, Elena Carafa (NG4167)

Titian, La Schiavona (NG5385)

Michelangelo, ‘The Manchester Madonna’ (NG809)

Veronese, The Adoration of the Kings (NG268)

Lotto, Giovanni Agostino della Torre and his son, Niccolò (NG 699)

Mantegna, Samson and Delilah (NG1145)

Ter Brugghen, Lute player (NG6347)

Costa, Battista Fiera (NG2083)

Luca Giordano, Perseus turning Phineas & his followers to stone (NG6487)

Rembrandt, Self-portrait at the age of 63 (NG 221)

Mantegna, The Agony in the Garden (NG1147)

************************************

Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1501), Madonna & Child, c.1465-70, marble relief, Bode Museum, Berlin, in complex parcel-gilt and polychrome Mannerist frame with knulled top edge, undulating vine carved on frieze and applied corner rosettes

************************************

[1] Now generally referred to as a ‘Medici’ frame

[2] See also Bronzino, Christ’s descent into Limbo, 1552, frame by Del Tasso, Santa Croce, Florence . The Fra Bartolommeo was destroyed in 1945

[3] Now attributed to Christoph Amberger

[4] Now known as the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

[5] Seen more clearly in Nicolaes Maes’s drawing after the work, now in the Ashmolean

[6] Probably by Peeter Neeffs, 1604

[7] Now in a Bolognese cassetta

[8] Missing from Berlin Friendrichshain Flak tower (Flakturm II) repository, Germany, in early May 1945

[9] Now in a reproduction black moulding frame, this was previously displayed in a scrolling leaf frame, which displaced Bode’s French frame in the 1950s

[10] Now in a reproduction parcel-gilt frame

[11] Now attributed to a follower of Rembrandt and Joshua Reynolds

[…] Mainardi (c.1460-1513), Madonna & Child with John the Baptist and three angels, Gemälgalerie, Berlin, in Schinkel frame with matching paterae in the […]

LikeLike

So glad to have found your extremely interesting blog. I own a cassetta frame that looks almost identical to the one on the Giorgione Giustiniani portrait – only mine is significantly larger, with the decorative elements applied in stucco. I inherited it from my grandmother, who came from an old Berlin family. It was certainly in her possession in the 1930s, and possibly much earlier, as she had it restored at that time (and apparently hated the result). Is it possible that this frame was copied in the 19th century, not unlike the frames made by the Medici Society in England?

I would be very grateful for any thoughts you might have.

LikeLike

I’m afraid that it’s impossible to make any comment on a frame solely through a verbal description; your best method of finding out about it would be to take it to your largest local museum – or, if you can get to the V & A, that would be best of all.

Good Luck!

LikeLike