Frames in paintings: Part 2 – the 17th century

by The Frame Blog

This is the second part of a series of articles on paintings in which pictures are shown hanging in their (often very realistically drawn) frames, giving some idea of the real contemporary fashions in displaying them – always remembering that the artist could be titivating them a bit, or imagining the whole setting, or that these might be hangs which had existed in that interior for some time. The first article on this theme dealt with Gothic, Renaissance and Mannerist frames in paintings from various periods and countries, and can be read here; this one covers Baroque works from a single century – a few Italian, British, Spanish and French, but the great majority from the Netherlands (Flemish, but mainly Dutch).

Introduction

Having said that, however, we begin with one painting from the mid-16th century, because framing in Britain underwent really very little change from one century to the next, pretty much until Charles I brought a large swathe of the Mantua collection into the country between 1628 and 1632. There were, of course, a few indigenous polychrome and gilded frames, which were probably reserved for royalty; for example, the recently restored and original red, black and gold frame, with rainsill and coats of arms, on the portrait of Katherine of Aragon (c.1520). Before the riches of the Gonzagas were poured into the Stuart galleries, however, even those in court circles seemed happy with a cabinetmaker’s frame in polished or black-painted wood.

Hans Eworth (c.1520-74?), Mary Neville, Lady Dacre, c.1555-58, o/panel, 73.7 x 57.8 cm., and detail, National Gallery of Canada

Here, therefore, is Lady Dacre with her first (executed) husband’s portrait in its stained, probably oak wood frame (just as though it were a photograph in a high street moulding), his age and the date inscribed on the frieze. Intriguingly, it hangs by what looks like a white shoelace – but is probably a lace for some other part of Lady Dacre’s clothing – from a large pin driven into the tapestry of damask roses in the background. The accuracy of all the detail in the painting – the blackwork collar and cuffs, the fur, posy and texture of the tapestry – are so convincing that the carefully-painted mouldings of Dacre’s frame and its informal hanger must be equally true to life. Perhaps the hanger indicates that the portrait always travelled with her, from her study to her bedchamber as well as to other houses she visited.

The early 17th century: Britain, Italy, the Low Countries

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (c.1561-1635), Sir John Kennedy of Barn Elms, 1614, and detail, Woburn Abbey

Nearly sixty years later, Sir John Kennedy had his portrait painted by the Flemish court painter Gheeraerts; he is clad in a staggeringly embellished suit, cloak and hat in which gold-wrapped thread almost covers the black ground, and the taste for which probably helped his slide into debt and the sequestration of his house and estate. This portrait records the peak before the fall, and also records the presence of a Lady (or putative Lady) Kennedy in the portrait peeping from behind its pink silk, gold-edged curtain. Gheeraerts may have painted this as well, celebrating either the betrothal or marriage; it is a precious enough object to require the curtain to protect it from dust, sunshine and impious eyes, and yet the frame is still a fairly ascetic narrow margin of black-painted wood, only softened by the two mouldings picked out in gold.

17th century Italo-Flemish school, Portrait of gentleman beside a framed portrait of a lady, c.1610-20, o/c, 104 x 91.1 cm., and detail, Sotheby’s, 8 April 2020, Lot 9

The Italian (or perhaps Flemish) version of the husband/fiancé with his wife/betrothed gives us a much prouder version of the relationship – the man drawing the curtain on his beloved’s portrait and gazing challengingly into the viewer’s eyes. The woman is no longer hidden but fully displayed in her youth and beauty, her pearl-embroidered gown and her lace headdress and ruff. The frame is part of the display; it is mounted with a metal rail which stands up above the top edge, with the silk curtain running freely on brass rings, unlike the curtain in Gheeraerts’s painting, where the curtain is hung on a wire along the front of the frame. The frame itself is also much wider and more opulent; the frieze is decorated at the corners and centres with gilded scrolling foliate flourishes and clasps – probably executed in sgraffito, as they gleam so brightly. Like the pose of the lover or husband, the presentation of the portrait has pride in every element, whereas Sir John Kennedy’s wife is tucked away (save for her hand, fan and skirt), in a modest frame, with a curtain which harmonizes with the prevailing colours.

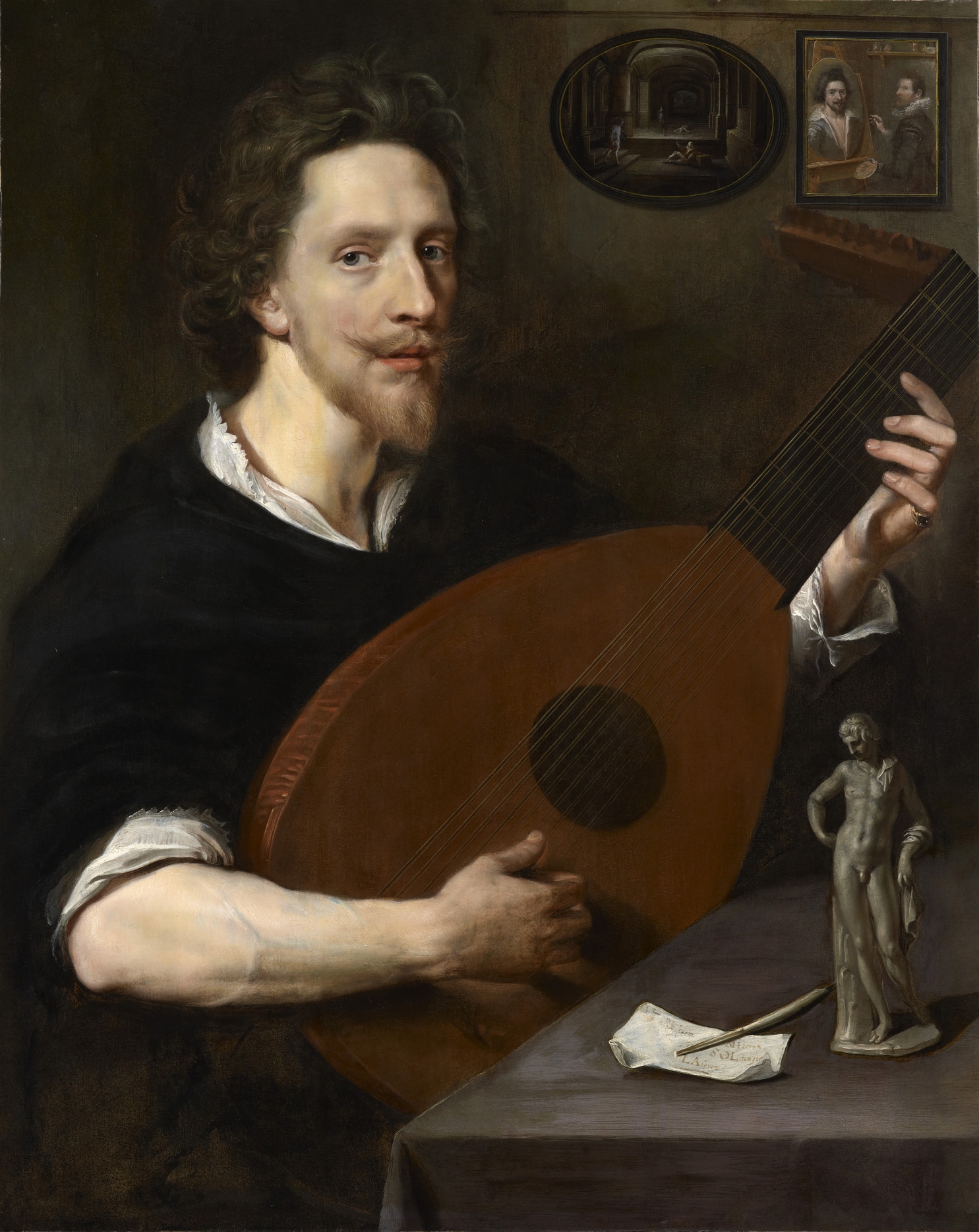

17th century Anglo-Flemish school, Nicholas Lanier, 1620s, o/c from panel, 31.4 x 67.6 cm., and detail, Christie’s, 8 July 2009, Lot 187

The portrait of Nicholas Lanier, painted slightly later still in the 1620s, has two background paintings in very simple frames. The oval is apparently The Liberation of St Peter by Hendrick van Steenwyck, with a play of narrow turned concave and convex mouldings and a tiny bead of gilt at the sight; the other picture, even more plainly framed but with a larger gilt sight edge, shows an unknown artist painting (possibly) the Duke of Buckingham. Ironically, it was Lanier, Master of the King’s Musick, who was sent to Italy by Charles I to buy art, and ended up alerting the king to the possibility of acquiring some or all of the Mantua collection, with all its wealth of carved giltwood and polychrome frames [1].

Jacopo da Empoli (1551-1640), The honesty of St Eligius, 1614, o/c, 300.5 x 190 cm., and detail, Gallerie degli Uffizi

Not all frames were as decorative as that royal collection, even in Italy, where stained and polished walnut became extremely fashionable in the 17th century – perhaps especially in Tuscany. This internal image of the Madonna and Child looks down on the patron saint of goldsmiths, St Eligius, from a parcel-gilt walnut frame which is extremely restrained with its severe lines, slightly canted reverse moulding, and sight edge set back quite deeply beneath the central gilded top edge. The profile and parcel-gilding lift it, as does the natty candle-branch beneath the painting; this swivels out from the wall, so as not to scorch the holy figures. St Eligius’s gold and silverware is lined up below the Madonna and Child, like an offering on an altar: the goblet, which is exactly centred below the frame, may in fact be a sacramental chalice. The whole ensemble of painting, frame, candleholder and shelf of plate thus becomes a sort of miniature work-place chapel in the embrasure of the rather strangely slanted arch.

Bartholomeus van Bassen (1590-1652), Renaissance interior with banqueters, 1618-22, o/panel, 57.5 x 87 cm., and detail, North Carolina Museum of Art

Bartholomeus van Bassen’s subject is the interior of a very secular palace, decorated with marble columns, coffered ceiling, massive chimneypiece, sideboard weighty with gold plate, and lots of art; but, in spite of the slightly louche trio in the foreground, a fully-fledged triptych of the Adoration of the shepherds with hinged shutters looks down on the scene. Like St Eligius’s Madonna and Child, it has a relatively sober frame of wood – in this case ebony or ebonized wood – with parcel-gilding. The ornamental cusped top of the altarpiece and the increased amount of gilding are the only indications of its sources from costly master artist and master framemaker, although its size and the format, with closing shutters which are probably painted on both sides, is unusual for a domestic sacred picture outside a private chapel.

The aedicular structure it’s mounted on, which seems at first to be another chimneypiece, perhaps with a smaller fireplace inside it, is presumably intended to be a kind of self-contained sacred niche, supporting the altarpiece and holding an altar table beneath it (another miniature chapel – this time in the dining-hall). None of this would be obvious without the shuttered frame of the Adoration, which even has rainsills at the base of the shutters. It provides the focus of the satire within the painting – the humble worshipping shepherds opposed to the ‘banqueters’ in their finery, and the Nativity above the drunken man, posed on the woman’s lap in an unholy pietà.

17th century Flemish School, Cognoscenti in a room hung with pictures, c.1620, o/ panel, 95.9 x 123.5 cm., and detail, National Gallery. Photo of detail: with thanks to Peter Schade

This – apart from the odd painting, which merges into the overall hang – is a wholly secular scene, outwardly and metaphorically. It seems to depict real connoisseurs of the time, admiring many paintings which are also real (or in the style of real artists), but in a gallery which is imaginatively vast, and which unites pictures which probably never hung together. The frames are especially interesting, as they appear to share in the accuracy which makes the paintings attributable to particular artists; so, in the detail above, the man in the embroidered yellow doublet holds in one hand a tiny picture in an ebony or ebonized frame, with a sliding cover which is pulled almost completely out. It reveals the contents to be a watercolour drawing of life-sized snails, beetles, and other things with many legs. This is evidence of one of these small covered frames in action (most of the covers have sadly been lost); they would have functioned as protection from the light for the watercolour, but also as the catalyst of surprise amongst friends or guests, who discover that they are holding, according to their own reactions, a meticulous scientific drawing, or a handful of creepy-crawlies [2].

17th century Flemish School, Cognoscenti in a room hung with pictures, detail

Other frames in the gallery are also interesting: not so much on the walls, which are hung with mostly plain or parcel-gilt ebony or polished brown wooden frames, but in the lower right-hand corner, where the obvious prizes of the collection have been assembled on the floor so that the men can examine them more closely. The nymphs and Demeter sitting in Elysian abundance by a river have an ebony cabinetmaker’s frame with gilt sight edge, as a foil to the brilliant colours of their paradise; but the scene with Alexander meeting Diogenes has a spectacularly decorative setting, perhaps marking it out as the most prized work. The outer moulding seems to be polished fruitwood, with an ebonized frieze and cavetto, all demarcated with lines of parcel-gilding. The frieze has additionally been decorated with vertebrate arabesques in sgraffito, which run continuously round the frame in a shimmering lacework border. This may be completely imaginary for the painting, yet frames like this were certainly made, to enhance the plum of a collection, to satisfy the collector, or – if a portrait – to glorify the sitter [3].

Behind it is another exotic design: the corners and centres of an ebony frame are decorated with what are almost certainly pierced and inlaid silver or pewter appliqués, set in their centres with small gold paterae or rosettes. Although these would be quite bright in full daylight, they shine subtly in their slightly shadowed position, and their corner emphases strengthen the diagonal compositional lines [4].

17th century Flemish School, Cognoscenti in a room hung with pictures, detail

Standing above another parcel-gilt frame, one of those Madonnas in a wreath of Brueghel flowers has been given what is either a frame painted to reflect the grey woodwork of the room where it usually hangs, or one which has been silvered and picked out in gold. Could this be an actual framing scheme from around 1620? It seems unlikely, possibly because of its resemblance to a 21st century high street moulding, but it seems unlikely as well that, amongst so much realism, the artist invented such an outré design. Perhaps there were others – early examples of frames silvered overall, and then topped bizarrely with parcel-gilt details – but they would have tarnished as quickly as later silvered frames, and probably had a second life as black frames picked out in gold. Beneath it, the frame of the Snyders still life seems even more sober in contrast.

Rubens (1577-1640) & Jan Brueghel the elder (1568-1625), The sense of sight, 1617, o/panel, 64.7 x 109.5 cm., Museo del Prado

But not every scene set in a gallery provides such apparently accurate depictions of the frames to be found there; the allegorical duet above, by Rubens and Brueghel, is very cursory as to frames; everything seems to be set in a simple, very narrow strip moulding, either ebonized or polished wood, varied by a few lines of parcel-gilding.

Rubens (1577-1640), The presentation of the portrait of Marie de’ Medici to Henri IV, c.1622-25, 394 x 295 cm., detail, Musée du Louvre

However, the copy of a related work by Brueghel has more interestingly realistic examples; and Rubens by himself can evoke extremely convincing contemporary styles, as in this detail of the vast canvas showing the French king encountering his potential bride via a portrait in a Baroque black and parcel-gilt frame. The gilded astragal-&-double bead at the sight edge is meticulously described; and – from the direction of Henri IV’s eyes – it may well be that this is what he is admiring, rather than the knowingly smug smile of the queen-to-be.

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), An antique dealer’s gallery, 1615-20, o/panel, 82 x 115 cm., and detail, Galleria Borghese, Rome

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), & David Teniers II (1610-90), Interior of a picture gallery, c.1640, o/panel, 58.5 x 79 cm., and detail, Courtauld Gallery

Frans Francken’s paintings of galleries (there are a lot of them) may appear to treat the frames as cursorily as Rubens in his allegories of the Senses, but, when examined, they generally have substance (proper variations of rail widths and profiles), different finishes (polished wood, wood and painted wood, ebony/ebonized wood, parcel gilding) and ornament (gilt beading, carved dentils), and have evidently been painted by someone who knows his contemporary styles as well as he knows the paintings which might have inhabited them. They give greater authenticity to his representations of gallery owners, dealers and connoisseurs, even though the patterns may provide only slight variations amongst them all.

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), Interior of a wunderkammer, d.1620-26, Quadreria della Società Economica di Chiavari Chiavari

His paintings of collectors’ cabinets of curiosities, which zoom in onto a single piece of wall and the table- or chest- top beneath it, tend to have simpler frames – presumably because everything is crowded more closely together, and there is a multiplicity of objects around and below. In the painting above, however, there are some particularly elaborate frames: three of various sizes with sgraffito decorations against a reddish brown frieze; a small oval silver (or ivory?) portrait frame; and a tondo with a polished wood (?) and parcel-gilt frame which has either been decorated in gold or inlaid.

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), Supper at the house of Burgomaster Rockox, 1630-35, o/panel, 62 x 97 cm., Alte Pinakothek, Munich

These convincing depictions have resulted in at least two frames for the National Gallery’s Samson and Delilah having been based on Francken’s Supper at the house of Burgomaster Rockox, which shows Rubens’s painting hanging over the chimneypiece (where it remained from 1610 to 1640).

Willem van Haecht (1593-1637), The gallery of Cornelis van der Geest, 1628, o/panel, 100 x 130 cm., and details, Rubenshuis, Antwerp

Similarly, Willem van Haecht’s evocations of collectors’ galleries and the versions of Apelles painting Campaspe present a range of very realistic and believable patterns, all variations on the cabinetmaker’s frames of the Low Countries, made of polished oak, fruitwood or ebony/ebonized wood (sometimes with parcel-gilding), with one or two friezes surrounded and separated by fine fillets and astragals.

Willem van Haecht, Apelles painting Campaspe, c.1630, o/ panel, 105 x 149 cm., Mauritshuis; collection of details

Several frames in the collection above also show the use of curtains to cover certain paintings [5], complete with their wires and curtain rings, indicating that – even in imaginatively constructed or idealized interiors – the details and mechanics of the setting are rooted in the real world.

Netherlandish School, François Langlois, c.1630-35, o/c, 91.5 x 68.5 cm., Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia

A realistic frame in a more realistic setting belongs to a dealer rather than a collector with fantasies, or, as described in the online catalogue entry for this portrait, ‘one of the most important figures in 17th century French art’, who bought and sold paintings, drawings and prints, and published engravings himself. The hollow ebony frame hanging from a nail on the wall behind him is probably waiting soberly for one of those prints.

The believability of these various frames with their curtains and hangers, and also their simplicity of profile, is emphasized in order to give weight to the things which don’t appear in any of these paintings – numerous as they are, and produced by Rubens, Francken, Brueghel, and later by Teniers, amongst so many others: none of them shows interiors in the Low Countries with ebony or fruitwood picture frames which have ripple mouldings, and particularly not those monster frames (probably German or Middle European, probably for looking-glasses) with outset corners, laden with torus, panel and frieze, ornamented with ripple, interrupted ripple and wave patterns.

The first half of the 17th century was the period when ebony-workers in Amsterdam began to multiply, prosper and become technically advanced in dealing with ebony, one of the harder woods. David Stafmaecker opened his workshop there in the 1590s, and in 1602 the Dutch East India Company was founded, increasing the amount of ebony imported into Europe.

Herman Doomer (c.1595-1650), cabinet, c.1635-45, oak, ebony, rosewood, mother-o’-pearl, ivory, 220.5 x 206 x 83.5 cm., Rijksmuseum

Herman Doomer arrived in Amsterdam from Germany as a teenager in 1613, and learnt from Stafmaecker; his own workshop would go on to produce mainly picture frames – with some furniture, like the cabinet above – and he seems to have supplied frames to Rembrandt, who painted portraits of Doomer and his wife (possibly to offset a bill). Rembrandt himself was obviously interested in frames, but they seem, from the available evidence, to have been Baroque with Auricular motifs, architectural, or (in the case of ebony frames) unadorned by any ripple mouldings.

Very few frames with ripple mouldings were included in the collection of almost a hundred original frames in Prijst de lijst, the innovatory catalogue of an exhibition of frames in the Rijksmuseum in 1984. The overwhelming numbers of styles were ebony and fruitwood frames, Auricular frames and trophy frames; and the ripple frames which found their way in had only one run of ornament (two, in a single case).

Rembrandt (1606-69), Girl in a picture frame, 1641, o/panel, 105.5 x 76 cm., Royal Castle, Warsaw

Rembrandt (1606-69), Agatha Bas, 1641, o/c, 105.4 x 83.9 cm., Royal Collection Trust

Both the pictures above are, in spite of first appearances, part of this consideration of frames shown in paintings, since in each case Rembrandt has included part of a frame around the edge of the painted composition. The Girl in a picture frame has quite a wide expanse of the lower moulding under her hands; it has a wide scotia at the sight edge, a step and a narrow astragal, but we are shown no more than that. What we can see, however, is that no ripple mouldings break the smooth sweep of the ebony; nothing detracts from the figure or intrudes on the illusion.

The portrait of Agatha Bas has a flatter profile – again with a deeper piece shown at the bottom, and narrow sides which rise to the edge of a capital (?) or a small, knopped motif. The sides (or the one on the right, which is lit so that it’s just visible) continue upwards to the top, but the capital, or whatever it is, is also the springing point for the spandrels of a dark arch, rising over Agatha’s head. Again, no ripples are involved.

It is interesting to speculate how these paintings would have been framed originally. Would the artist have taken them to Doomer or an equally talented ebony-worker, and asked him to complete the painted frame with a wooden frame which followed the hints given him? This would have meant a frame with three equal sides and a much smaller width on the bottom rail, but it would have been worth it just to fulfill the illusion. The Polish wooden frame is so nearly there, if the sight edge and most of the bottom rail were cut away. The Royal Collection frame should go altogether, since it is clear from the evidence in the painting that Rembrandt did not want any ripple mouldings in the completion of his trompe l’oeil effect.

The mid-17th century: Spain, France, Italy

It has already been pointed out that stained and polished walnut was fashionable in 17th century Italy, and it was, of course, used for versions of the wooden cabinetmaker’s frame which was so prevalent in the north.

Leandro Bassano (1557-1622), Portrait of a widow at her devotions, first half 17th century, o/c, 105 x 88.5 cm., and detail, private collection

Leandro Bassano, son of Jacopo Bassano, shows a domestic altarpiece which has no ornament or decoration at all – no shaped contour, no carving or gilding, no painted arabesques. It frames the joyful scene of the Virgin’s birth, but even this is set in a gloomy grey stone bedchamber, furnished and floored in dark wood, and the frame echoes this – its Baroque profile of raised mouldings and deep scotias and hollows is a faithful depiction of a frame in this style, and also a symbolic representation of the darkness of the widow’s life.

Pier Francesco Mola (1612-66), Socrates teaches the young self-knowledge, c.1640-50, o/c, 120 x 98.5 cm., Museo d’arte della Svizzera Italiana, Lugano

Mola’s frame is much less darkly Baroque; it is a flatter cassetta with interestingly stepped mouldings, and a cheerfuller, warmer tone, more suited to youth and the doorway to a good life, but it is also meticulously observed and recreated.

Master of the Vanitas Texts (fl. Madrid c.1650), Vanitas with a vase of flowers, looking-glass, hourglass, &c., one of a pair, 50 x 66 cm., Dorotheum, 10 May 2017, Lot 161

The Spanish Master of the Vanitas Texts (a striking name, but hardly anything seems to be known about him – or, of course, her) has a different but equally symbolic take on the frame within a painting. His prop in these specific examples is a giltwood reverse cassetta, which appears in at least three works as the frame of a looking-glass; although presumably producing a framed painting is just as vain an object as assessing the flaws in one’s person. It is fundamentally the same frame, with minor variations of carved ornament (the two below have a flowered back edge), and decoration of the frieze (from the top image downwards: punchwork corners and centres; continuous scrolling foliage in punchwork; raised pastiglia corners and centres). The frame can be suspended via a brass ring and a tasselled cord – black and gold or red and gold.

Master of the Vanitas Texts (fl. Madrid c.1650), Vanitas with a looking-glass, candle, hourglass, &c., o/c, 49 x 65.5 cm., Sotheby’s, 4 July 2013, Lot 225

Master of the Vanitas Texts (fl. Madrid c.1650), Vanitas with a vase of flowers, looking-glass, hourglass, &c., o/c, 46.5 x 61 cm., Dorotheum 17 April 2013, Lot 615

The text which gives this artist his or her name appears in several works; it is ‘Vana est pulchritudo’, or ‘Beauty is empty’, and these frames are indeed very beautiful. The Master may be Neapolitan as much as Spanish, accounting for the very Italian cast of his frame (although all the separate ornaments can be found in Spanish frames); there was considerable diffusion of style and pattern through the Habsburg empire of Flanders, Spain, Naples and Sicily, and Milan, in the 17th century especially. Craftsmen and merchants travelled continually through this large chunk of Europe, looking for work, carrying out commissions, transporting things such as pattern-books and objets d’arts of divers fashions.

Simon Vouet (1590-1649), The toilet of Venus, 1629, 183.8 x 153 cm., Cincinnati Art Museum

Painting might equally well immortalize beauty as a produce a sermon against valuing it. Simon Vouet’s Venus at her toilet has two very nice looking-glasses in which to admire herself; one has an octagonal frame with a stepped ogee profile, a carved astragal-&-double bead, and an animal’s head at the top (is that a subtle warning, however? – the ape of folly or the goat of lust?).

Simon Vouet (1590-1649), Venus at her toilet, c.1640, 164.9 x 114.5 cm., Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburg

The other has a more Italianate leafy frame, with clasps at top and bottom, a large hanging ring and cord, and a complete absence of finger-pointing animals. Whilst the Master of the Vanitas Texts uses a frame which might just as well contain a painting, as does the first of Venus’s frames, this one seems made specifically for a looking-glass – a division of function which emerges with various styles.

Pierre Mignard (1610-95), Henriette de Coligny, comtesse de la Suze, second half 17th century, o/c, 51 x 41.1 cm., Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly

French portraits are generally a reliable source for faithful representations of contemporary picture frames; in the mid- to late- 17th century they are mostly in Louis XIII style, often with a convex profile or a leafy torus. Here is the Comtesse de la Suze, swept skywards in a crowd of amorini and a gilded garland of bay leaves-&-berries; this motif has the advantage of being ubiquitous, and so not having very much overt meaning, but simultaneously having significance there if needed. Thus, it can indicate that she deserves a wreath of bay leaves for winning a contest (for beauty or accomplishments or being blessed by Apollo), or that she is just a charming face in an attractive golden frame.

Noël Coypel (1628-1707), Anges présentant le médaillon de Louis XIV, and detail, Rennes, Musée des Beaux Arts

On the other hand, if the sitter is Louis XIV, then symbolism becomes much more important. This frame is coloured, so as to become a garland of real bay leaves bound with ribbons, conveying the king’s excellence in all appropriate fields (little though he seems to appreciate the compliment), and yet it still remains a solid wooden frame.

Jean Garnier (1632-1705) after Claude Lefebvre (1632-75), Allegory of Louis XIV, protector of the Arts & Sciences, 1670-72, o/c, 174 x 223 cm., detail, Château de Versailles

Here is Louis as a younger man in his thirties (although he had already been king for a quarter of a century, and looks steeped in cynicism). The frame, in one of the styles named after his father, is exactly the same (save for the colour) as that on the much older portrait by Coypel; but – having looked at the latter – we can see the point of the oval frame with its running imbricated bay leaves: it may really be an undercover indication of godlike power and achievement. To underline this point, there are sunflowers at the top and bottom of the oval; they are attributes of Apollo, and symbolize the arts in particular – the theme of the painting.

French school, Portrait of Jean Pointel, c.1650, o/c, 78 x 98 cm., Alexandre Landre Maison de Ventes, 1 October 2023, Lot 41. With thanks to Moana Weil-Curiel

This portrait came onto the market a year ago, in October 2023, and is particularly interesting for the combination of frame and painting presented to the viewer. It is assumed to be the portrait of Jean Pointel, one of Poussin’s patrons; the painting shows a slightly inaccurate piece of Poussin’s Landscape with ruins (1642) in the Prado , apparently owned by Pointel before it found its way into the Carlo Maratti collection in Rome, and thence to Philip V of Spain; but – more importantly – he (or Poussin) has framed it, not in one of the perfectly plain and undecorated Roman gallery frames which are stacked in the background of Poussin’s self-portrait in the Louvre, but in a contemporary Louis XIII convex frame carved with acanthus leaves and a spiral ribbon at the sight edge.

Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), Self-portrait, 1650, o/c, 98 x 74 cm., Musée du Louvre

Perhaps it’s time to leave the very plain frames to the paintings which stayed in Rome, and to admit that the works which Poussin sold or gave to his French patrons were far more likely to be framed according to the Parisian fashions of the day [6].

Sébastien Bourdon (attrib., 1616-71), A man holding a framed portrait, 1665, 107.3 x 91.5 cm., Schorr Collection, London. With thanks to Moana Weil-Curiel

Sébastien Bourdon, who lived (like Poussin) in Rome, although much more briefly, and also worked in Stockholm as the court painter, seems to have developed a panEuropean style in his art. The window in the portrait above gives onto an idealized Poussinesque Roman landscape, and the Baroque frame on the internal painting seems to be made of Italian walnut, with a parcel-gilt fluted ornament at the sight edge. Perhaps the whole work looks back to his youth in Rome, although the clothes, ribbons, hair and moustache of the sitter date from the 1660s. The raking flute is a clever ornament to have chosen for the nested painting – whether it framed the actual portrait or not – since it functions like a run of mini-arrows, lit up with gold leaf and all pointing inwards towards the second sitter.

The mid- and later 17th century: Flanders and the Netherlands

The Baroque art of the Low Countries is where by far the most numerous depictions of framed paintings hanging in interiors are to be found. There seem to be hardly any rooms, unless in the poorest houses and taverns, where there are no paintings, maps or engravings; and many middle-class, mercantile houses appear to have almost as large a collection as those of the gentry and nobles. The frames also seem mostly to be drawn very accurately, which is why this section starts with the dismissal of David Teniers the younger.

His various paintings of the picture collection of the Archduke Leopold Wilhelm formed a sort of pictorial catalogue, which was the precursor to a printed version illustrated by engravings. However, accurate as the individual pictures might have been, within the various views of the gallery in Brussels, the frames as he showed them cannot be trusted.

David Teniers II (1610-90), details from the various views of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm’s gallery in Brussels, painted from 1651-53

These details show the same pictures as represented in several paintings, with different frames (mouldings and finishes), including four versions of Titian’s Jacopo Strada in three different frames, and, at the bottom, three differently-framed versions of Titian’s Violante [7]. This being so, and in spite of his fame, the paintings’ fame, and their place in depictions of collectors’ galleries, he really has no place in this article.

Polished oak and fruitwood frames

The interiors of houses in the Low Countries form a large part of the subject matter of paintings in the 17th century – or, rather, of their backgrounds. This is probably why the idea has grown up, fostered by dealers reframing Flemish and Dutch paintings from the French Baroque frames given them by collectors, that the only correct frame for a painting of this period and source is an ebony or ebonized one.

It is true that there are a great many black frames in these paintings, but there are also a lot of variations on their material and finish, and – just as there are some very beautiful polished oak and fruitwood frames on the outside of the paintings – so there are also some on the inside. See also the odd wooden frame popping up in the picture galleries of Frans Francken and Willem van Haecht, already mentioned.

Bartholomeus van Bassen (c.1590-1652), Interior of a palace, Castello Sforzesco, Milan

Van Bassen’s palace, although idealized, has a fruit- or oak- wood frame with gilded sight for what is presumably the most important painting in the collection, the scene with Adam and Eve on the chimneypiece. There is a darker wood and parcel gilt frame on the side wall, possibly stained or even painted.

Jacob Duck (c.1600-67), Scène galante, c.1635-40, o/panel, 40 x 68 cm., and detail, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nîmes

Here, a very much scaled-down interior – although with a handsome doorcase and carpet – is hung with an ebony frame containing a biblical scene (Salome receiving the head of John the Baptist?), and two very plain wooden frames with a landscape and conversation picture; the frames are depicted cursorily, unlike their contents, but are clearly differentiated from the ebony frame. This might well be a smaller parlour in Bartholomeus van Bassen’s imaginary palace – a cosier place, where the inhabitants and their friends go to play risqué games or charades, but which is still furnished with a variety of art, even if the frames are more workaday.

Egbert van Heemskerck (1634/35-1704), Jacob Fransz., surgeon, and his family, 1669, 70 x 59 cm., and detail, Amsterdam Museum

An even more modest room belonging to a barber-surgeon has paintings which also have wooden frames – a dark stained oval above the door, and a very simple tray-like cabinetmaker’s frame, probably of oak, with parcel-gilt sight beside it. These have no polished lustre or complex mouldings or multiple lines of gilding, and perhaps reflect the fact that, at a time when art seems to have been everywhere – in churches and municipal buildings and homes of all sorts – the ownership of a painting or two was a sign of arrival at a certain social level, or even of aspiration towards it, and that economy in framing might help this.

Flemish School, Interior of the Linder Gallery, 17th century, o/copper, 56.5 x 82.2 cm., and detail, private collection, via Nicholas Hall Gallery, New York

This intriguingly detailed depiction of a picture gallery, exploring the collaboration of art and mathematics through the relationship of painting and drawing, contains so many accurately represented objects that it is impossible not to give the frames of the paintings as much credence as the various scientific instruments – especially the frames hanging nearer the two red damask-covered tables. Even if they aren’t pictures of actual framed paintings, they are so realistic that they at least bear witness to there being frames exactly like this, at that time.

Above the table on the left is a Triumph of Dionysos in a fruitwood frame with a complex of ebonized mouldings on either side of the frieze; and beneath it, an oval painting of the Holy Family in a wreath of flowers – one of those Brueghel and Rubens co-operations – in a turned wood frame also with very fine mouldings.

Flemish School, Interior of the Linder Gallery, detail

On the other side of the room, another Triumph (of Poseidon or Thetis) has a matching fruitwood and ebonized frame, and an almost round flowerpiece has an oval scotia frame with fine mouldings. Finally, the little standing portrait of a painter and (perhaps) his patron discussing a drawing is framed very decoratively, in a stained and polished wooden frame inlaid with silver or pewter scrolls, with gilded astragals and an ebonized top moulding – all highly, and very meticulously, finished.

Gerard ter Borch (1617-81-), The letter, 1650-60s, o/c, 70 x 54 cm., and detail, State Hermitage Museum

Another fruitwood frame, or perhaps a frame veneered with panels of figured wood and parcel-gilt, holds a portrait next to two ebony-framed landscapes. Light picks it out; perhaps the sitter is the writer of the letter, the husband of the reader and provider of the rich carpet and the satin gown, but also a man for whom a frame of golden wood is symbolically enough.

Ebony and ebonized frames

Of course, there are humungus numbers of black frames overall in these paintings; there is nearly always one lurking somewhere in a corner, and – where the hang is more crowded – they do very much outnumber other frames in other materials. Many of them are painted almost in four strokes – four flat rails, without form or dimension; the best ones, however, have recognizable and clearly differentiated patterns and profiles, and there are also variations with parcel-gilding and ornamental gilt mouldings.

Vermeer (1632-75), The concert, c.1664, o/c, 72.5 x 64.7 cm., Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (stolen 1990), Factum Arte reconstruction, 2017, and detail

This sadly stolen Vermeer contains a really beautifully painted ebony moulding frame, which is why, in order to illustrate it properly, the image used here is taken from the Factum Arte reconstruction made in 2017. This clarifies the profile, and the silky ebony sheen of the wood. The ter Brugghen, hanging to its right, seems to have a similar frame, but is harder to distinguish.

Pieter de Hooch (1629-84), A maid and a child in a pantry, c.1656-60, o/c, 65 x 60.5cm., and detail, Rijksmuseum

Similarly the frame on the portrait shown here (a very Shakespearean head), hanging by a window in the politer part of the house than the foreground, has a very clear structure, with a Baroque ogee outer moulding of such depth that, at an angle, it obscures the bottom part of the frieze. This frieze is lit to a silvery grey by the daylight falling full upon it. You can even see the tiny bevelled sight edge and one of the mitred joints.

Gabriël Metsu (1629-67), Woman reading a letter, c.1664-66, o/panel, 52.5 x 40.2 cm., and detail, National Gallery of Ireland

Metsu is another artist who carefully describes the profiles of the frames in his paintings. Here, on the left, is a looking-glass frame with a dynamic Baroque reverse profile, pushing the smallish piece of glass forward towards the viewer. It comprises a series of stepped and canted mouldings – quite different from the conventional frame profile on the right, which is also stepped, but inward, towards the painting, and has concave and convex mouldings.

The looking-glass frame also appears to have three narrow runs of ripple moulding, on the top and sight edges and around the centre of each rail; the first ones to appear as yet, standing in contrast to the pretty complete lack of any ripple mouldings applied to the picture frames depicted in these paintings, and very modest indeed compared with the massive ripple-infested looking-glass frames (probably not even made in the Netherlands) which 20th century taste has for some reason insisted on applying to great 17th century Flemish and Dutch paintings.

The two frames have fittings, as well, which give more information about how paintings and looking-glasses were hung at this point. The looking-glass has a tripartite gilt or brass claw at the top which holds the hanger, and is decorated with a bow of ribbon; another claw is just visible at the bottom, above the woman’s hood. The picture frame is fitted with a curtain rail which stands proud of the top, and which holds rings for the curtain – green, and probably silk – which may indicate a particularly precious work, but in the context of this painting may just be there for the maid to draw back, revealing the painting underneath as a metaphor for the stormy course of love and life.

Metsu (1629-67), A man and woman seated by a virginal, c. 1665, oil on panel, 38.4 x 32.2 cm, and detail, National Gallery

This Metsu has a similarly wide and Baroque reverse form as the looking-glass frame in the Woman reading a letter; it is a solid object with a shaped profile and depth, and its companion on the right-hand wall, seen almost edge on, has the same realistic depth – so much so that, as in other paintings, it is being used to hold the curtain back from the window, letting light flood in from the right.

Parcel-gilt ebony and ebonized frames

François Bunel de Jonge (attrib., c.1550-post 1593),The seizure of the contents of a painter’s studio, c.1590, o/panel, 28.1 x 47 cm., and detail, Mauritshuis

A very simple form of black and gold frame was around for a very long time; probably for at least half the 16th century – as this painting from the last decade of it shows – and on, through the 17th. The poor artist whose wares are being seized for debt or some other defalcation has, apart from one or two examples, stuck rigidly to an ebonized frame with two lines of gold around it, which does for history paintings, sacred subjects, flowerpieces and small portraits.

Gabriël Metsu (1629-67), The hunter’s present, c. 1658-61, o/c, 51 x 48 cm., and detail, Rijksmuseum

In the 17th century this pattern is still one of the most frequently seen, although the number of gilded lines or mouldings may change…

Pieter Codde (1599-1678), A woman holding a looking-glass, 1625, o/panel, 38.1 x 33.7 cm., National Gallery, NG2584

…and the moulding may be clarified by images such as this, where an almost side-on view shows the top edge painted black, a narrow line of gold beneath it, a black moulding canted down to the half-gold, half black frieze, and finally the gilded bevel at the sight edge. The back edge is also canted, in a parallel incline to the front – it slopes back to the wall, a large wedge of it cut away from each rail so that it weighs less and looks a lot more elegant.

Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617), Hercules (upper image), 1613, o/c, 207 x 142.5 cm., with detail of Minerva, below, c.1611, o/c, 210.5 x 116 cm., Frans Halsmuseum

These are the kinds of frame which are being shown in these paintings: the back edge inclined in to towards the wall; a gentle ogee canted down from a flat top edge via a series of steps and convex mouldings to the frieze; and further small steps, ogees and astragals to the sight edge. Three of them contain and are original to Goltzius’s great images of Mercury, Hercules and Minerva in the Frans Halsmuseum. There is another pair of almost identical original frames on Michiel van Mierevelt’s 1620 portraits of Frans Dircksz Meerman and Maria Ijsbrandsdr de Bye in the Deutzenhofie, Amsterdam [8].

Pieter de Hooch (1629-post 1684), Interior with mother & child, 1665-68, o/panel, 36.5 x 42 cm., Amsterdam Museum

Later paintings have a wider rail, usually with a varied profile, and just a small gilded sight edge; perhaps more of these are ebony, rather than the more generously parcel-gilt, earlier and probably ebonized frames?

Ebony & ebonized frames with parcel-gilt ornament

Emmanuel de Witte (1617-92), Portrait of a family in an interior, 1678, o/c, 68.5 x 86.5 cm., Alte Pinakothek, Munich

At some point in the mid-century or later, the plain gold lines which were the main form of decoration for ebonized frames developed a much more decorative cast, being replaced by narrow lines of gilded ornament. This fashion may possibly have been influenced by the frames of miniature paintings. There is an example in this group portrait, in which the family’s possessions and clothes (even their garden) have been called on as props, to demonstrate their prosperity and social standing. Interestingly, there are four diverse visible frames – the marble chimneypiece, which contains a looking-glass (far too high to see into, but a welcome enhancement of light on gloomy days), another looking-glass beside it at a more human height, which has a large giltwood Auricular frame, and the two frames facing us, which are ebony or ebonized, and have two different gilt ornaments at the sight edge.

Emmanuel de Witte, Portrait of a family in an interior, detail

The one on the extreme left, of which only one edge can be seen, seems to have what might be an astragal-&-several beads moulding (or could it be a rolled leaf between something else?), whilst the one above the head of the paterfamilias has a clearly-drawn gilded zigzag round the sight edge. This frame evidently holds a valuable painting – a church interior, possibly one by Emmanuel de Witte himself – as it’s protected by a green silk curtain on a brass rail, while the painting itself is held by brass hangers above and hooks below. The gilded sight edge must be a special touch; it has been applied to a wide, probably ebony, cabinetmaker’s frame, and may represent a carved leaf tip running around the sight edge.

Gillis van Tilborgh (c.1625-78), Family portrait, c.1665-70, o/c, 81 x 101 cm., Museum of Fine Arts Budapest

This similarly rich interior by the Flemish painter Gillis van Tilborgh, a pupil of David Teniers II, with its walls completely covered in embossed gilded leather, has a trio of landscapes in apparently identical parcel-gilt frames, hung a couple of inches below the ceiling where the introduction of art can’t impinge too much on the inhabitants. The central painting turns out to have (less excitingly than the frame of the Emmanuel de Witte) a beaded ogee sight edge, but which is still however more ornamental than a plain gilt line [9].

Gillis van Tilborgh (c.1625-78), Elegant interior with twelve gentlemen, 1660s, o/c, 139 x 209.5 cm., and detail, Sotheby’s New York, 1 February 2018, Lot 39

Another work by Van Tilborgh shows a private picture gallery, where one of the frames is decorated with a much more elaborate gilt ornament; this may have been more popular in Flanders, with its Spanish connections, than with Dutch collectors and clients. The three large pictures along the back wall, and the small coastal scene propped against the chair at the right, have ebony moulding frames with alternating stepped ogees and hollows; they are unrelieved by any gilding, or any decoration at all save the small coloured bows which flop over the top centre of the three large ones. The satin sheen of these frames and depth of glossy black forms the perfect foil to the colours of all the paintings. The large still life (perhaps by Joris van Son) on the chair itself has a Baroque reverse moulding frame, and is also densely black with soft reflections; this work has a plain gilt sight edge.

It is the large painting above it which has the most interesting frame. It is comprised of a very narrow ebonized flat plate or frieze, which creates a reverse profile in combination with the proportionately much larger convex gilded sight edge. This seems to be decorated with leaves, and perhaps small Auricular motifs, tiny trophies, or even symbolic elements which may help to explain what is happening in the painting. It is certainly very different from most other parcel-gilt frames at this time.

Flemish School, Interior of a picture gallery, c.1670, o/c, 48 x 82 cm., Sotheby’s, Old Masters, 18 April- 8 May 2019, Lot 121

This may be another private picture gallery, although the crammed walls and the gestures of the men might suggest that they are there to buy, rather than for a social call. The frames all seem to have the structure of the one on Gillis van Tilborgh’s scene of figures, but in different proportions, as it were; so that one frame has a barely visible ebonized frieze around the contour and a tiny gilt moulding, another has a wider frieze with the same moulding, and others again have relatively larger mouldings, including one of the two miniatures in the centre of the composition.

This may, course, be a sort of livery frame, like the ‘Salvator Rosa’ frames in the palazzi of Genoa, or the ‘Kent’ frames in British country houses, or it may simply be a quirk of the artist, but the effect is much more like a commercial gallery with a house style of framing, and where the client is indicating that he would rather have the postcard-sized landscape than its very large brother. This may perhaps be the work of Van Tilborgh’s workshop in Brussels.

Gillis van Tilborgh (c.1625-78), A picture gallery, 1660-70, 97.2 x 129.5 cm., and details, Spencer Museum of Art

Gillis van Tilborgh (again) turns up with another gallery full of counterintuitive 17th century Flemish frames, in which the large ornamental sight edges have now morphed into a version of French Baroque Louis XIII patterns, but with a more meandering and undulating flowered and berried foliate design. The interior space and some of the characters inside it seem suspiciously close to the gallery and figures in the Flemish School painting above, as does the close hang from floor ceiling and the statuette on the table; but the slightly disapproving female presence has gone, to be replaced by – can it be a portrait of Van Tilborgh himself, or one of his assistants, touching up another landscape for patron (or dealer)?

Louis XIII-style gilded frames

Van Tilborgh’s apparent ubiquity in the area of 17th century Flemish frames with ornamental gilded sight edges and ebony/ebonized friezes, or quantities of gilded Louis XIII-style frames all in one place, is striking – although there must be many other examples of painted Flemish interiors with these frames.

Johannes Siberechts (1627-c.1703), Interior with a woman embroidering, 1671, o/c, 59 x 59 cm., and detail, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

One is this interior by Johannes Siberechts, an instance which leaps out as possessing a giltwood torus frame in true French Louis XIII-style. It is gilded overall, and has a garland of bay leaves on the torus, and an astragal-&-triple bead at the sight edge; it is much more French in appearance than Van Tilborgh’s patterns. As well as the ebony frame lurking behind the bed, it hangs with an ebonized frame with decorative gilt sight edge over the chimneypiece.

In the second half of the century the Netherlands relaxed from sober protestantism into the more opulent influence of the French Baroque, and produced both their own versions of Louis XIII patterns, and something closer to the original French model; most of the indigenous versions have vanished, a prey to later fashions, but their memory remains, in the paintings where they appear. As a general rule, houses in the Netherlands seem to display only one gilded frame in whichever interior is depicted – or very occasionally two; none of them look like or are hung in such profusion as Gillis van Tilborgh’s, and there is a wider stylistic spread of designs (Auricular frames are a different kettle of fish and will be explored below).

Gerard ter Borch (1617-81), The concert, 1670-80, o/panel, 57.1 x 45.7 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin https://id.smb.museum/object/869262/das-konzert

Here, for example, is Gerard ter Borch’s narrow moulding frame, more suitable for a modern watercolour, partnered by an ebony frame above the harpsichord.

Vermeer (1632-75), The guitar player, c.1672, o/c, 53 x 46.3 cm., Kenwood

More fashionably, Vermeer’s guitarist sits beneath a landscape in a (probably French) Louis XIII frame.

Vermeer, The guitar player, detail of painted frame inside Louis XIII garland frame. Photo of latter: Arnold Wiggins & Sons Ltd

This is described in flat strokes of colour and is a very long way from a photorealistic image, but – if compared with an actual example of the style – it can be seen to be a very accurate interpretation of a bay leaf garland frame, the leaves turning alternately from front to side, scattered with berries and centred with flowers. The corner acanthus leaves are also very faithfully indicated, and the sight edge suggested as an astragal broken into long beads, or the top sections of a spiral ribbon.

Gérard de Lairesse (1640-1700), Filip de Flines, 1682, o/c, 141 x 115 cm., and detail, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel

Oval versions of Louis XIII frames also proliferated, usually for portraits – but here the collector Filip de Flines is portrayed against a background containing the fabrics he dealt in, and which have paid for his marble walls, modish kimono, and decorative oval landscapes in imbricated bay leaf garland frames.

Vermeer (1632-75), Young woman standing at a virginal, c.1670-72, o/c, 51.7 x 45.2 cm., National Gallery

A similar fat torus of imbricated bay leaves frames a landscape in another Vermeer; this one is rectilinear, but the frame is markedly different from the one behind Vermeer’s guitarist, the bay leaves taking up almost the whole width of the rail between a beaded and an ovolo moulding.

Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627-78), An elegant couple playing cards, o/c, 65.3 x 77.8 cm., and detail, Christie’s, 13 October 2009, Lot 64

Van Hoogstraten breaks the general rule of one gilded frame per interior view, and does it in more than one of his works. In this scene all the paintings have gilded frames: the one on the side wall at the left is strangely flat and undefined, but the still life above the seated couple has a Louis XIII reverse frame with an acanthus leaf ogee; the oval overdoor landscape has a torus, possibly with bay leaves; and the large painting seen through the door has another torus frame, with a frieze at the back edge. They may be faithfully drawn from a real interior, but even if they are recreations by the artist, they seem to bear witness to a scale of patterns ranging from Dutch Baroque, through a native variant of a Louis XIII pattern, to a possible French version of the style.

Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627-78), The anaemic woman, c.1667, o/c, 69.5 x 55 cm., and detail, Rijksmuseum https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-C-152

Another collection of Hoogstraten frames in The anaemic woman is perhaps more questionable. In this painting there are five gilded frames: through the first doorway and internal window a series of four almost square pictures – the only one we can see fully is probably a mythological scene – hang in frames with a Louis XIII profile, where the torus takes the form of a large rope or cable moulding, like the shape of a turned spiral chair leg. Through the further doorway, a massive gilded frame over the chimneypiece, carved with a figure at the corner and flowers, leaves and fruit, holds a painting of crouching figures. This style is sometimes known as a ‘Lutma’ frame, usually indicating an Auricular base (melting and sinewy carved forms) overlaid with realistic foliage and fruit. Here, however, there seems to be no Auricular element, and this frame may be as imaginary as perhaps the rope frames are.

Frames in paintings can thus be variously very good records of recognizable styles, either in a real interior which was part of a portrait or group portrait, or brought in by the artist to furnish such a painting, like an added still life of objects; or perhaps they may be iterations of a real frame used in a painting to ‘stock’ a picture gallery (perhaps around similarly imported representations of his own or well-known pictures); or possibly they are made up by the artist altogether, as the easiest way of providing an improved setting for a portrait, or a suitable setting for a subject painting.

Auricular and trophy frames

Auricular frames form a strange small stylistic movement by themselves – mostly Mannerist, with a smidgeon of Baroque, they seem to derive partly from late 16th century silverwork, partly from engravings of ‘leatherwork’ cartouches, and partly from a contemporary scientific interest in anatomy, shells and other marine creatures. Influences from the Low Countries in the early 17th century also seem to have flowed to Britain, creating a local style of Auricular frame, and then ebbed back across the North Sea to help shape the frames which were designed and made there in the second half of the century.

Abraham Liedts (c.1604-68), The Company of Captain Dirck Veen, 1653, 202 x 368 cm., Westfries Museum, Hoorn

What is usually referred to as the earliest surviving example of these later Auricular frames (called ‘Kwab’ in Dutch) was carved for the 1653 group portrait by Abraham Liedts of one of the defensive militia companies; this one protected Hoorn, and the painting of its members hung in the Old Town Hall there (now Westfries Museum). The ground structure of the frame is formed of shifting, melting, scrolling segmental forms, which undulate along the rails of the frame [10], and into which carved military trophies have been added. The trophies – mainly weapons – only decorate the lateral rails, which are wider than the two horizontal rails.

As the earliest known Auricular frame in the Netherlands in the mid-17th century, however, it may have been pipped to the post by another:

Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588-1629), Sleeping Mars, 1629, o/panel, 106.5 x 92.8 cm., reframed c.1650, Centraal Museum, Utrecht

The extraordinarily rich and sculptural trophy frame of this Sleeping Mars, painted in 1629 but reframed c.1650, has probably been made in emulation of a 16th-17th century Italian cassetta mounted with trophies, but the entire ground of the frieze is carved as a complete animal hide – it is almost literarily a ‘leatherwork’ frame. This is easier to see on the horizontal friezes, which are carved with striking bands of curly, sinewy Auricular ornament beneath the spears and shields. Although not a public piece of art like the Hoorn militia painting, the Mars might have become quite widely known in the art world through its ownership by the artist and collector, Martin Kretzer.

Gerard ter Borch (1617-81), Woman washing her hands, c.1655, o/panel, 53 x 43 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

Frames in this style evidently became very fashionable quite quickly, and started popping up in painted interiors. Already by 1655 Gerard ter Borch was introducing them into his interior scenes; the two depicted here have the broken outer contours of Auricular frames, and are covered with small, twining and curving segmental shapes. They indicate that the house is furnished in the height of fashion, and that its owners may be aristocratic and are certainly wealthy.

Gabriël Metsu (1629-67), Woman seated at a table & man tuning a violin, c.1658, o/c, 43 x 37.5 cm., and detail, National Gallery

Five years later, in 1658, Metsu painted a large Auricular frame in which the underlying structure of scrolling, segmental ornaments, arranged in trumpet-like shapes around the rails, uses the same vocabulary as Liedts’s group militia portrait at Hoorn. It appears as a background setting or prop, again to indicate that this particular scene is set in a prosperous household, which can afford monumental carved stone chimneypieces and expensive imported carpets. Because it furnishes a domestic interior there are obviously no military symbols; instead small flowers are entwined in the upper rail, and there also seems to be a central heart-shaped cabochon (?). Like other items in an interior, a frame of this sort can carry symbolic information – just as the real objects did.

Vermeer (1632-75), The glass of wine, c.1658-60, o/c, 67.7 x 79.6 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Around the same time or shortly afterwards, Vermeer furnishes one of his own interiors with an upright Auricular frame around a landscape, containing a large house under a stormy sky. Since the emblem in the stained-glass window advises temperance and restraint (perhaps especially between young females drinking wine and dashing young cavaliers offering it), this internal painting may refer to the dark clouds which can follow a lack of restraint. The frame itself is more ambivalent, however; it is one of the ‘Lutma’ sub-category, including fruit, leaves and flowers in between the sinewy scrolls and segmented horns – as well as luxuriantly unrestrained bunches of grapes.

Gabriël Metsu (1629-67), Jan Jacobsz Hinlopen & his family, c.1662, o/c, 72 x 79 cm., Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

The Auricular frame in Metsu’s portrait of the Hinlopen family may be doing something else again. It’s another massive piece of gilded sculpture, in the centre of the wall, and has a green silk curtain on a brass rail half-concealing it and its painting. The latter seems to be a landscape from what can be seen of it; but what if it is more than that?

On the left side of the frame is a ladder-shaped motif, and beneath it, by the bottom left corner, a bunch of what seem to be sharp nails; the central crest of the frame is formed by an angel with spread wings rising up at the top. This seems to suggest that what is taking place beside those dark trees in the painting is the Crucifixion, the way of the Cross, or perhaps the descent from the Cross; and that it is there, in the centre of wall, room and family, to advertize – subtly – the uprightness and Christian morality of this wealthy merchant. Like the Hoorn portrait of the town’s militia in an Auricular frame with military trophies, Metsu’s portrait also boasts an Auricular trophy frame with symbols contained in it; but this one is an internal frame, with a religious message.

Gabriël Metsu (1629-67), Woman writing a letter, c.1662-64, o/panel, 39.4 x 33.5 cm., The Leiden Collection

Gabriël Metsu (1629-67), The lacemaker, c.1661-64, o/panel, 35 x 26.5 cm., Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Metsu’s genre scenes with a female employed in the actions of a cultivated woman – writing to an absent husband in the company of the dog of fidelity; making lace, perhaps for a trousseau, next to a homemaking cat – are furnished with large Auricular frames in the background, holding a seascape or a landscape, and seeming to be purely decorative themselves (although the seascape may refer to the storms of life and love, and the landscape to happy and tranquil love). It is difficult to regard them as uncluttered by significance, when their writhing, scrolling ornament is the most dynamic and restless part of each painting, but here they are probably used, again, as part of the scene-setting of fashionable and wealthy houses.

Gabriël Metsu (1629-67), Man writing a letter, 1664-66, o/panel, 52.5 x 40.2 cm., National Gallery of Ireland http://onlinecollection.nationalgallery.ie/objects/8708

The Man writing a letter might be seen merely as one of this series of single figures reading, writing and sewing in peaceful, well-appointed homes – his pendant, Woman reading a letter, c.1664-66, also in the National Gallery of Ireland, was mentioned above, under ‘Ebony and ebonized frames’ – save that the putative symbolism in the internal paintings of the Woman writing and The lacemaker has been made clearer and more important in this pair.

The Woman reading a letter does so in a room furnished with ebony frames and chair, and a painting of ships on a stormy sea (revealed by her maid drawing back its curtain, as she reads); her lover or husband writes in front of a peaceful family of goats in a landscape from which the clouds are clearing. And the frame is a beautifully carved Auricular design, laden with swags of bay leaves and fruit, with one of Venus’s doves nesting happily at the crest.

Emanuel de Witte (1617-92), Interior with a woman playing the virginals, 1665-70, o/c, 77.5 x 104.5 cm., Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam

By the second half of the 1660s (and surely before), there are Auricular looking-glasses [11] which speak of wealth through their own opulent gilded detail, and use it for message and meaning. Here is one which employs the same symbolism as the picture frame in Metsu’s Man writing a letter; it is replete with supporting amorini crawling through the marine motifs and shells, and is therefore probably meant to suggest a dedication to love and Venus (the whole painting may be about the melancholy of love, with music – the food of love – nourishing the languid figure in the scarlet bed). This is less a frame than a very large piece of elaborate sculpture which dominates a third of the room, forming, with the figure at the virginals, one of a trio of vertical sections, along with the illuminated scarlet bed and its occupant and the central panel of receding rooms and maidservant,which articulate the composition.

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout (1621-74), Four officers of the Amsterdam Coopers’ & Wine-rackers’ Guild, 1657, o/c, 163 × 197 cm., and detail, National Gallery

There are other internal trophy frames depicted in paintings; one is the frame in the background of Gerbrand van den Eeckhout’s group portrait of officers belonging to the Coopers’ and Wine-rackers’ Guild. The portrait dates from the early years of the evolution of Auricular frames in 1657, but the painting behind the four men has a frame which seems earlier, with a simple architrave profile which is mainly frieze and on which the tools of the guild members are arranged; the whole piece has then been gilded.

The models for the frame seems to be Italian trophy frames or frames influenced by them, such as the reverse cassetta with military trophies which had been given to Hendrick ter Brugghen’s Sleeping Mars in 1650. This reframing appears to have happened when, as noted above, the Mars entered the collection of an artist, Martin Kretzer of Amsterdam, whose collection was publicized – also in 1650 – in a poem by Lambert van den Bos.

Perhaps the literary celebration of such an extraordinarily elaborate frame stimulated the Coopers’ and Wine-rackers’ Guild to have their own trophy frame made – either for an existing painting of their tools in action, or possibly in tandem with a new painting for their headquarters. Whatever the history of that frame, none of the (very early) Auricular ornament which distinguished ter Brugghen’s frame is visible in Eeckhout’s painting of the Guildsmen; perhaps it was reserved for the original physical frame of the portrait itself?

Gerard ter Borch (1617-81), Group portrait of the magistrates of Deventer, 1667, o/c, 186.2 x 248 cm., in a trophy frame carved by Derck Daniels, Town Hall, Deventer

Ten years after the portrait of the Coopers and Wine-rackers, Gerard ter Borch executed a large and ambitious group portrait of the town council of Deventer, where he had moved in 1664, and whose inhabitants (many of whom he was connected to through his father, his stepmother, his wife, and his position on a civic advisory board) he painted individually [12]. The group portrait was commissioned after the refurbishment of the old Town Hall and Wanthuis in the 1660s, which included the repanelling of the council chamber (the raadzaal). The frame for the portrait was made by the carver who also produced the sculptural swags and garlands for the updated Town Hall interior and the trophies on the new council chamber pedimented back to the mayor’s chair (1659), Derck Daniëls (1632-1710) [13]. This last object,

‘…bearing the arms of Deventer on its pediment, was decorated with various tangible symbols of authority such as clusters of arrows, shackles and chains, rolls of paper and bundles of pens, interspersed with snakes and festoons’ [14].

It can be seen in a photo from 1959, although contrarily and rather confusingly ter Borch sets his portraits against the previous, older panelling.

A panel mounted with six executioners’ swords (one of a pair), 1660s, framed by Derck Daniëls, Town Hall, Deventer. Photo: Deventer Burgerscap, Facebook

Daniëls’s frames for two panels of executioners’ swords and a painting of The Last Judgement (now vanished) can be seen on the back wall of Gerard ter Borch’s group portrait, and the panels of swords still exist – however, the frames seemed to have suffered in translation, as what ter Borch painted doesn’t look very much like what we see today.

Gerard ter Borch, Group portrait of the magistrates of Deventer, details of left-hand sword panel and Last Judgement from the background (apologies for poor quality of image)

The frames of the panels of swords in his painting are gilded Auricular patterns, with brushstrokes which may be meant to convey indications of the sunflowers, carved manacles and instruments of punishment on the actual frames, but which really just look much like generalized Auricular ornament.

The frame of The Last Judgement in the painting is also Auricular, but with more projecting centres and corners, and a large crest at the top. Angelic figures seem to be clinging to the sides, although there may be a figure of Satan or one of the damned on the right-hand side, next to the painted representation of the condemned being cast into hell. The golden crest may be a halo or mandorla of small angels, and the central cabochon may suggest the figure of God the Father, but this could equally be wishful thinking. Daniëls apparently made this frame, like the others, but since the painting has disappeared there is no evidence as to whether ter Borch changed what was actually before him for something which would light up the back wall of his own painting with a square of fashionable gold.

Alison Kettering, in her article on ter Borch’s Deventer portraits, points out that, rather than reproducing a realistic view of the council in session, the artist was creating a metaphorical image of good governance and justice, and to this end he played about with the interior of the council chamber, as well as with the individuality of the councillors [15]. This is a helpful note as to images of frames in paintings; they may tell us a lot about the framing fashions of the time, but what they tell may be less – or more – than the truth.

**********************************************

For more on Auricular frames, visit the Archives of Auricular style: frames.

‘Frames in paintings: Part 1 – Gothic, Renaissance and Mannerist’ can be found here.

**********************************************

[1] The portrait of James I (died 1625) by Mytens at Knole, Sevenoaks, NT, has a carved blue and silver-gilt frame, but this may well be a later addition, catalyzed by the enthusiasm for more gilding, colour and ornament which grew in the wake of the acquisition of the Mantua collection

[2] See ‘An introduction to frames with covers, shutters and curtains. Part 3: Curtains and covers on secular paintings and looking-glasses’

[3] See ‘Exploring frames in the Royal Collection’, and notably Hans Eworth’s Elizabeth I & the three goddesses

[4] The fashion for frames with metal appliqués (brass, gilt bronze, silver, pewter, and even papier maché) is explored in ‘Nicolaes Maes: original frames, French fashions, metal appliqués’

[5] See note 2

[6] The first version of Poussin’s Self-portrait (1649; now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) was also owned by Jean Pointel. It has been slightly reduced in size, and now has a ‘Salvator Rosa’ frame

[7] NB This is how Titian’s Jacopo Strada is now framed , and this is Violante (both Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna)

[8] See P.J.J. Thiel & C.J. de Bruyn Kops, Prijst de lijst, Rijksmuseum, 1984 (translated as Framing in the Golden Age, 1995), cat. nos 6 and 9; also Michiel van Mierevelt’s Portrait of Johanna van Heyst, 1627, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

[9] See also Van Tilborgh’s Elegant company, 1655-75, o/c, 61 x 78 cm., in which narrow ebony or ebonized frames are depicted with gilded sight edges almost the width of the black moulding, and which also seem to have engraved decoration

[10] See, too, Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen’s pair of portraits, Jasper Schade and Cornelia Strick van Linschoten, from 1654, which have the earliest surviving individual Auricular portrait frames in the Netherlands. The frame of the militia portrait is described in detail in Prijst de lijst, op.cit., cat. no 33, pp. 210-11

[11] There are also large, purely decorative and wealth-displaying Auricular looking-glass frames in Emmanuel de Witte’s Portrait of a family in an interior, 1678, and Pieter de Hooch’s Woman handing a coin, 1670, Sotheby’s New York, 4 June 2009

[12] Alison McNeil Kettering, ‘Gerard ter Borch’s portraits for the Deventer elite’, Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, vol. 27, no 1-2, 1999, p. 54

[13] Jan ten Hove, et al., ‘Deventer’, Monumenten in Nederland. Overjissel, 1998. For Derck Daniëls’s frame for Gerard ter Borch’s Group portrait of the magistrates of Deventer, see Prijst de lijst/ Framing in the Golden Age, op. cit., cat. nos 58, pp. 273-74

[14] Kettering, ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[…] Here, therefore, is the first part of a collection of paintings (very far from exhaustive) from various periods and countries which contain detailed depictions of framed works, and which can tell us something about the style of frame in churches, public buildings and houses at those times, and in those places. They might be frames which had already hung in the interior in question for a considerable time, or they might be brand new and avant-garde for the period, but they are of great help to those currently trying to give authentic settings to the paintings for which they’re responsible, or to anyone who wonders what really went around the art that they’re looking at. Part 2 is here. […]

LikeLike