Pastiglia in Italian Renaissance cassoni of the 14th–16th centuries

Professor Svetlana Nikolskaya

This paper was given at the conference ‘Pastiglia decoration’, held on 18th November 2025 at the State Museum of Fine Arts of the Republic of Tatarstan, Kazan. Because pastiglia decoration, both as a firmer, moulded and cast auxiliary material, or as applied directly to the object in a more liquid form, has been of great importance for the ornamentation of frames, all the presentations given at the conference – including those not specifically dealing with picture frames – are relevant to the latter. Professor Nikolskaya’s paper, in considering its use in the decoration of Renaissance cassoni, implies its potential influential on other items in Italian interior of the 14th-16th centuries.

*

During the 14th to 16th centuries, Italy saw a notable expansion of practical possibilities in all fields of artistic activity. New pigments appeared in painting; architecture and urban design introduced new styles and theories of design; the language of iconography acquired additional layers of meaning; traditional crafts and materials were refined and improved; and the creation of a specialized vocabulary became another essential component of the various arts.

Sala dei Pappagalli, Palazzo Davanzati, Florence

In the history of interior design, the Renaissance is marked by a process which can be described as ‘the birth of the room’. Interior spaces began to be differentiated from each other as part of the development of a new architectural type, the urban palazzo. A vivid example is the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence, built in the 14th century and now a museum of the Renaissance interior [1].

Sala dei Pavoni (displayed as a bedroom) and bathroom, Palazzo Davanzati, Florence

The existing layout already distinguished the sala (the hall), the camera (bedroom/sitting room), and the studiolo (a private room in which the master of the house could read and study, and where he kept his own collections and drew up contracts). These last two rooms were accompanied by agiamenti (toilet facilities), an area which formed a precursor to today’s bathroom and water closet. The kitchen was located some distance from the living quarters to avoid unwanted odours, and to reduce the danger of fire.

16th century Venetian gilt and polychrome strongbox, with original lock and key, 1stDibs

There were few furnishings. Storage objects such as chests, caskets, and cases played a particularly important role. Their variety in form, size, materials, and construction emphasized the function of each room. For example, a studiolo could contain a cassaforte (or strongbox) – a wooden chest, covered by a lattice of iron bands, with complex locking mechanisms concealed under an iron sheet.

The camera, a more private space than the sala, housed the cassoni – large, richly decorated wooden chests which were an integral part of wedding ceremonies, and therefore occupied a special place in the home. The decoration of wedding cassoni was characterized by a combination of several technical and technological methods, including pastiglia. Two objects from the display at Palazzo Davanzati illustrate the two different forms of pastiglia, as they were described by Cennino Cennini (fl. c.1370–c.1440) in Il libro dell’arte, or The craftsman’s handbook, written in the late 1390s [2].

Cassone with applied panel on the façade, with scenes of The judgement of Paris, c.1440-60, carved wood, pastiglia, parcel-gilt, tempera paintings, 60 x 142 x 49 cm., Palazzo Davanzati, Florence

The judgement of Paris cassone; details of the painted scenes and their pastiglia ‘frames’

The first piece is the original front panel of the chest above, with painted scenes depicting The judgment of Paris, surrounded by very fine pastiglia decoration with scrolling foliate patterns and rinceaux. These raised decorations were modelled in gesso made with lime sulphate. The gesso was first laid in several flat layers, which were burnished in order to give them a silky texture, upon which the relief ornaments were applied with a brush, using the same liquid pastiglia. In essence, the scrolls and rinceaux were ‘dripped’ onto the flat gesso’d panel, and once they were dry they could be tidied up and sharpened. This version of pastiglia is described by Cennino Cennini in his manual in chapter CXXIV [3]. The pastiglia is modelled smoothly in gentle gradations of relief, and painted with colours which accentuate the forms and supply details of the decoration.

Sienese cassone, c.1380-c.1420, poplar wood, iron, tin, pastiglia, parcel-gilt and polychromy, decorated with fleur-de-lys, 57 x 143 x 55 cm., Palazzo Davanzati, Florence

The second cassone from the Palazzo Davanzati shows the technique described in chapters CXXVIII and CLXX of Cennini’s Libro dell’arte : ‘How to take relief ornaments from a stone mould…’ and ‘How to make caskets or chests’:

‘You may also get a stone, carved with devices of any style you wish, and grease this stone… Then get some tin foil; and, laying some fairly moist tow on the foil (which lies over the mould), and beating it as hard as you can with a willow mallet, you then take gesso grosso ground with size, and fill up this impression…’ [4]

Sienese cassone, c.1380-c.1420, details

The resulting pastiglia ornaments could be applied with glue ‘on a wall, on chests, on stone…’, and gilded. This particular cassone has an iron frame and five wrought iron straps which cross the convex lid – a rare example of a forziere or strong-box, which belonged to the Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova in Florence [5]. It is decorated with coats of arms and an overall pattern of fleur-de-lys motifs, cast in pastiglia as Cennini describes.

Mantuan (or Florentine?) cassone, c. 1509, with original finish, gilded and painted blue on moulded pastiglia, 62.5 x 154.4 x 47.5 cm., V & A

Another impressive example of the practical implementation of Cennini’s descriptions is the cassone in the V & A, dating from around 1509. The coat of arms on the front of this chest suggests that it was made for Francesco Maria I della Rovere, Duke of Urbino from 1508-16 and from 1521-38. In 1509 he married Eleonora Ippolita Gonzaga, daughter of the Marquess of Mantua and Isabella d’Este, exactly the event to trigger the commission of such a richly decorated chest.

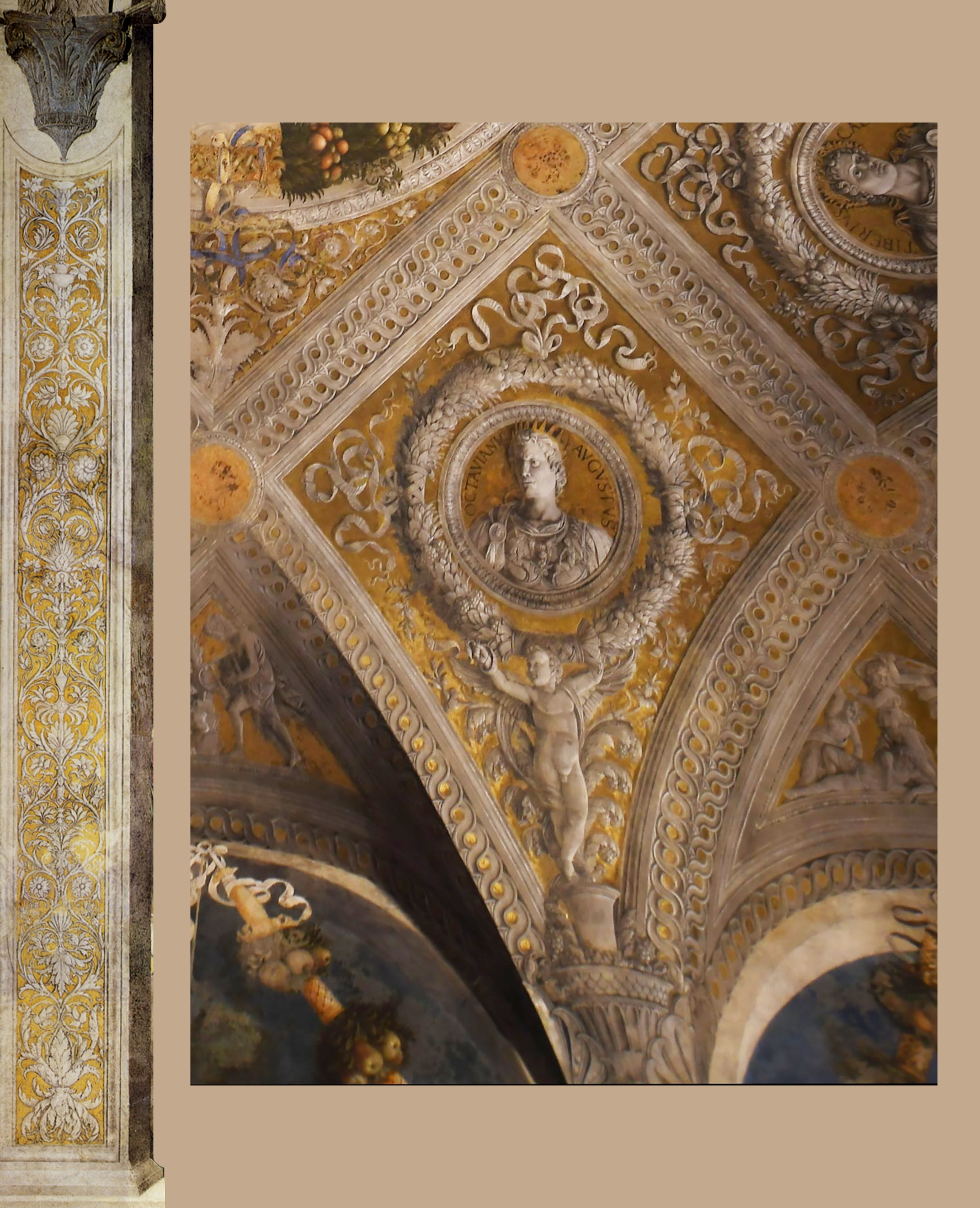

As well as the coat of arms, which is set in a beribboned cartouche in a circular laurel wreath, the decorative scheme includes candelabrum ornaments incorporating eagles or phoenixes, flanked by scrolling flowered stems. All of these are visually related to the painted ornament on the walls and the ceiling of the Camera degli Sposi in the Ducal Palace, Mantua, decorated by Mantegna, the court painter.

Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), details of frescos in the Camera degli Sposi, 1465-74, Palazzo Ducale di Mantova

Elements from the Mantuan cassone, such as the wreath surrounding the coat of arms, the twisted ribbons at the base of the façade, the candelabrum motif and scrolling stems ending in leaves and rosettes, as well as echoing motifs from Mantegna’s work, can be recognized in many pastiglia-decorated objects from the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

The south and east walls of the Camera degli Sposi are painted in trompe l’oeil, mimicking the embossed textures of leather wall-hangings. The room functioned as a studiolo for Ludovico III Gonzaga, as well as his state bedroom, and the space formed by these two adjoining walls would have housed decorated pieces of furniture, such as a bed and cassoni – similar to the one in the V & A. It is no coincidence that the period of the Italian Renaissance can rightfully be considered the beginning of the ‘art of interior design’, when various materials and crafts, objects, styles and colours interacted together, demonstrating harmony in their diversity.

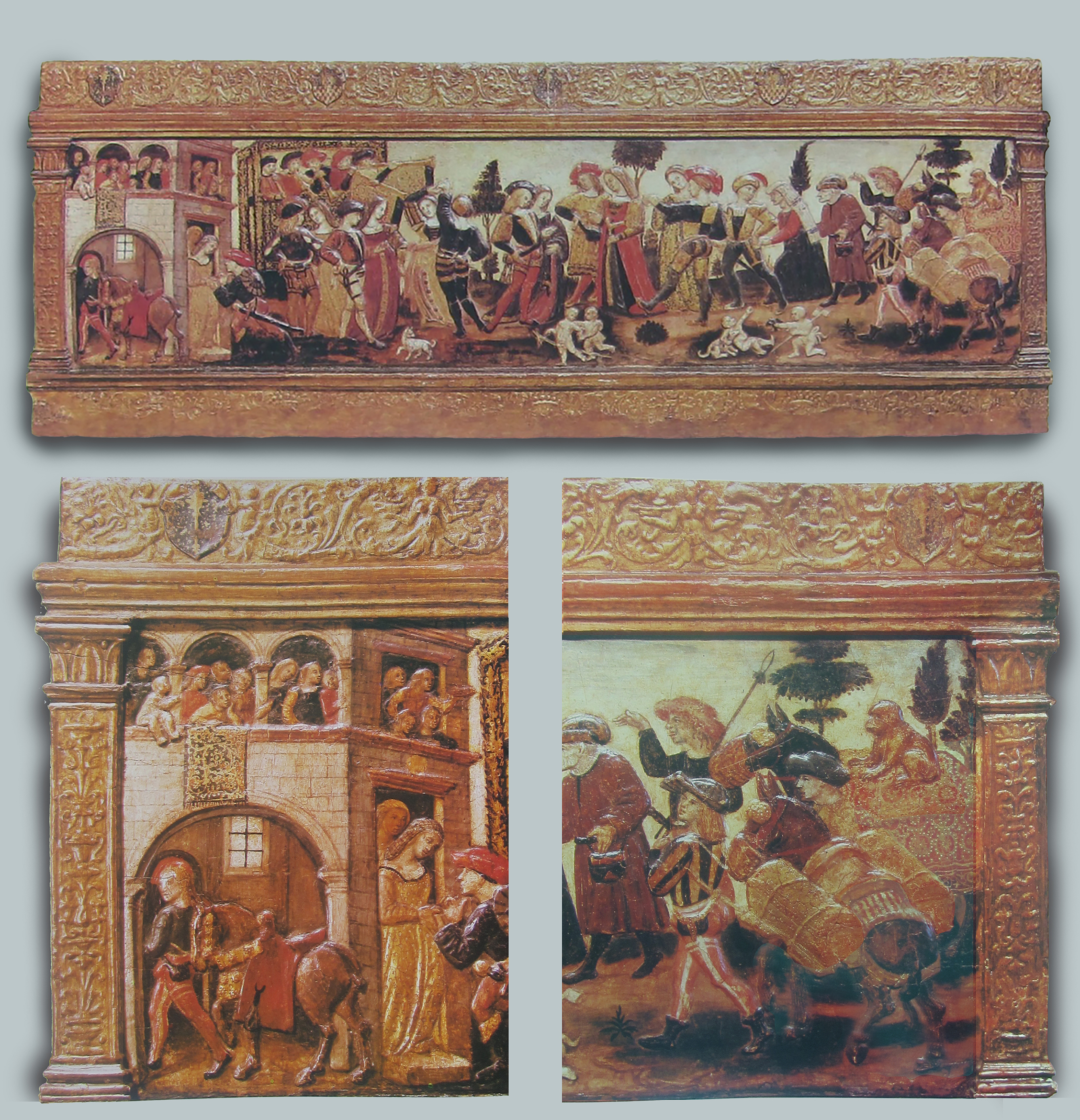

Mantegna (attrib., 1431-1506), Bartolomeo Melioli (attrib., 1448-1514), complete cassone, 101 х 230 х 86 cm., its façade, 67 x 212 x 13 cm., and the façade of its destroyed pair, 66.5 x 212 x 13 cm., decorated with relief scenes with the fairness of Trajan, 1477 or earlier, carved giltwood with pastiglia, gilding and polychromy, Museum of Carinthia (the Klagenfurter Landesmuseum), Klagenfurt am Wörthersee, Austria

The design of a unique commission, attributed to Mantegna and probably carried out in his workshop with the help of the sculptor, medal maker and goldsmith, Bartolomeo Melioli, is now in the collection of the Museum of Carinthia in Austria. These are the façades (one with its surviving cassone) of two wedding chests made on the occasion of the marriage of Paola Gonzaga, daughter of Ludovico III Gonzaga, in 1477.

Detail of the complete cassone with The departure of Trajan…, attributed to Mantegna’s design, Museum of Carinthia

The two preserved façades feature pastiglia reliefs: The departure of Trajan for Asia and The justice of Trajan. It has generally been believed that the creators of these compositions used engravings made after works by Mantegna. However, since the reliefs feature

‘…the first realistic depiction of a Roman military campaign in the Renaissance, it would be strange for such early and archaeologically accurate images of a Roman triumphal procession to have appeared without Mantegna’s involvement… It should also be noted that the commissioner of this pair of wedding chests must have been a member of the Gonzaga family….we must assume Andrea Mantegna’s participation in the design, although no definitive evidence has yet been found’ [6].

The four objects from Palazzo Davanzati, the V & A and the Museum of Carinthia, which have been discussed so far, demonstrate how the range of the artistic possibilities of pastiglia expanded between the 14th and 16th centuries: from earlier compositions with heraldic symbols rhythmically arranged across the entire surface of a cassone, through exquisite ornamental relief motifs and trompe l’oeil ‘carpets’ and ‘curtains’, to figurative images in quite deep relief.

Façade of a cassone with wedding scene, second half 15th century, poplar wood, pastiglia, parcel gildings and polychromy, 49 x 167 cm., and details, State Hermitage Museum

A particular aspect of the history of pastiglia in the decoration of furniture is this practice of combining pastiglia ornament with narrative figurative painting, especially in the finishing of cassoni. As a rule, pastiglia is most often present on surfaces which serve as frames and borders for pictorial compositions. However, the State Hermitage Museum houses the front panel of a Florentine cassone from the second half of the 15th century, with wedding scenes which demonstrate an extraordinary technique: figurative characters, both painted in the flat and modelled in pastiglia, appear in the same pictorial field [7].

The narrative composition occupies almost the entire surface of the wood, with flanking pilasters decorated with candelabrum ornament and a frieze above the cornice holding scrolling foliation, flowers and grotesques interwoven with heraldic devices. The lower frieze is partially preserved. The pilasters, friezes, and foreground figures are executed in relief pastiglia, while the landscape background and the figure of a servant farther from the viewer are painted on the flat ground. This object can be identified, with a high degree of confidence, as the piece described by Peter Thornton, who, discussing a special type of ‘travelling cassone‘, refers to an example depicted in a ‘Russian collection’ [8].

The term pastiglia, which describes a surface-decoration technique, is closely connected with the Renaissance perception of the material world. The decoration of traditional utilitarian objects became an indicator of artistic taste, social status, and the owner’s position within the family hierarchy. Pastiglia gained popularity due to its versatility as a craft, enabling a wide range of approaches to surface treatment, and demonstrating reciprocal influence with other forms of artistic practice (painting, engraving, metalwork, ivory carving). In the Renaissance, pastiglia was not merely a technique of surface ornamentation. It can be regarded as an expressive tuning fork for the interior as a whole – a whole stylistic element in itself. It is no coincidence that the history of pastiglia in furniture and interior decoration would experience such a brilliant continuation in the 17th and 18th centuries.

*********************

Professor Svetlana Nikolskaya holds an Associate’s Chair at the Institute of Design and Art, Nizhny Novgorod State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering (NNGASU), Nizhny Novgorod, Russian Federation

*********************

[1] Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani and Maria Grazia Vaccari, eds, Museo di Palazzo Davanzati: Guida alla visita del museo, Florence, 2011, pp. 240

R C P Pisani (text) and M G Vaccari (ed.), Palazzo Davanzati: a house in mediaeval Florence, Florence, 2011, pp. 64

[2] Cennino Cennini’s The craftsman’s handbook, translated by Daniel Thompson, Yale University Press, 1933; republished by Dover Books, 1954 & 1960. For the translation of the relevant sections of Cennini, see ‘National Gallery, London: a Venetian pastiglia frame‘

[3] Ibid., chapter XXIV

[4] Ibid., Thompson’s translation of Cennini, Dover, 1954 & 1960, p. 78

[5] A very similar fleur-de-lys cassone, with a provenance from the Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova, was bought by the Met Museum, New York, from the collection of the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini

[6] Daniela Gregori, ‘Die Brauttruhen der Paola Gonzaga: Zu Herkunft, Ikonographie und Autorenfrage der Cassone-Tafeln im Kärntner Landesmuseum‘, 1999, p.16

[7] Liubov Faenson, introd. and ed., Italian cassoni from the art collections of Soviet Museums, Leningrad, 1983, p. 264

[8] Peter Thornton, The Italian Renaissance interior 1400-1600, New York, 1991, p. 201