Artcurial: ‘Rêveries fin-de-siècle’: a sale of Symbolist works

The art historian and dealer Gérard Lévy (1934-2016) opened the gallery which bears his name in the 1960s, on Rue de Beaune in Paris. It specializes in objects from China, Japan and Tibet, and also in historic and early photographs; it is now run by his daughter, Patricia. Lévy was a collector, as well, assembling a notable group of more than eighty decorated fans from the 18th and 19th centuries, and he also collected Symbolist paintings, which were beginning to enjoy a new interest after decades of dismissal.

These paintings – along with books (many of them illustrated) by some of the literary figures connected with Symbolism – will be sold in Paris by Artcurial on 11th February 2025. Although much of Lévy’s collection is being sold without frames, and some of the remainder have rather clunky modern mouldings, a few of the paintings retain their original artists’ frames, or the settings given them in the spirit of Symbolism.

In the words of the auction house, Lévy was a

‘…great enthusiast and visionary, [who] contributed to the rediscovery [of Symbolism] by collaborating on one of the first exhibitions dedicated to the fin-de-siècle in Zurich: Neue Kunst in der Schweiz zu Beginn unseres Jahrhunderts, preceding the major exhibitions of the 1970s.

Gérard Lévy was passionate about Symbolist art, and had already built an extraordinary personal collection. Works by Carlos Schwabe, Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, and other major figures of Art Nouveau adorned the walls of his family apartment, reflecting his deep attachment to this movement. Gérard Lévy never sold any works by Symbolist artists. The collection, now being dispersed by Artcurial, reveals the intimate tastes of a dreamer, his first loves, those he had chosen for himself.’

*

Lot 4 Carlos Schwabe (1866-1926), Spleen et Idéal, 1907, based on his illustration for Les Fleurs du mal by Charles Baudelaire, 1900, watercolour & gouache with pencil, 20 x 27 cm. (10.63 x 7.87 in.), in its original frame, chosen by the art critic Gabriel Séailles (1852-1923)

Provenance: Gabriel Séailles Collection; Collection of his wife Octavie Séailles, née Marie Virginie Octavie Paul (1855-1944) [label on the back]; then by descent to his daughter Andrée Séailles (1891-1983); acquired from the latter on September 4, 1970 by Gérard Lévy; Gérard Lévy Collection; then by descent

Like many Symbolist paintings this one has been given an ornamental aedicular frame, gently reinforcing the mythological nature of the struggle Schwabe depicts between the spiritual and the material. It was lucky in its owner, being acquired – presumably directly from the artist – by an art critic, philosopher and writer (whose subjects included genius in art, Leonardo and Watteau), and who reflected the decorative inclinations of the Symbolist movement in his choice of setting. The writhing forms of the painted figures are picked up in the friezes of undulating vines, and the Art Nouveau style of capitals and column supports.

Carlos Schwabe (1866-1926), Le tonneau de haîne/Medusa, post-1899, watercolour & ink on paper, 63.8 x 49.6 cm., Musée d’Orsay

Schwabe’s Le tonneau de haîne in the Musée d’Orsay is similarly framed in a 19th century setting, and was also in the Gabriel Séailles Collection, although the image with frame on the museum website indicates that it may be the artist’s, rather than the collector’s, choice. The flurry of large and busy ornament – like Spleen et Idéal – includes grapevines, but here the effect of the frame is not to isolate and focus on the painted figures, but to encroach claustrophobically on a scene of carnage and hate, which adds to the sense of chaos and the subversion of natural laws.

Carlos Schwabe (1866-1926), L’Ideal, 1913, o/c, 198 x 114 cm., Sotheby’s, 19 January 2006

Another example of related framing, this time on a much larger scale, enhances the feeling of pure and unfettered aspiration in the image, revealing how the use of one particular frame rather than another might be used by the artist (or even the patron) in the service of Symbolist art.

*

Lot 7 Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921), Défiance [Distrust] (Lilie), c. 1893, photograph enhanced with pastel and coloured pencil (original assembly, monogrammed ‘FK’ at the bottom), 16.5 cm. diam. (6.5 in. diam.)

This is one of around ten photographs (by Albert-Edouard Drains, or ‘Alexandre’) of the original drawing, all of which were modified with pencil, pastel and/or coloured pencils by Khnopff himself, making each individual and unique. This particular version has also been given a tinted mount with a circular sight, which crops the image and closes in on the face of the sitter, removing extraneous detail and focusing on the intent gaze of the eyes. This is Khnopff’s original mount, bearing his monogram just off the bottom centre of the sight edge.

Khnopff (1858-1921), Secret-reflet, 1902, pastel and coloured pencils on paper, 50 x 31 cm., Groeningemuseum, Bruges. Photo: Hugo Maertens

The frame, with its faux-marbre pilasters and undulating foliate ornament on the entablature, may – like the mount – have been chosen by the artist, who favoured historical revival frames of various kinds. Secret-reflet of 1902 is one of these, with its Baroque-style strapwork, foliate and shell frame; it also repeats the circular sight of Lot 7, and the tinted mount (Khnopff’s later mounts and inlays tend to be gold).

Khnopff (1858-1921), Encens, 1898, o/c, 86 x 50 cm., Musée d’Orsay

Lot 7 can also be compared with Khnopff’s Encens in the Musée d’Orsay, with its small aedicular frame designed by the artist. If the frame of Lot 7 is not the artist’s own, it is at least an informed hommage by a collector. The setting of Encens pays its own homage to Burne-Jones, who had been introduced to French artists and writers by their critics’ positive reactions to his work in the inaugural exhibition of the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877, which was also shown at the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris. This ‘led in the 1880s to the perception of Burne-Jones as one of the precursors of Symbolism’, and in 1889, Burne-Jones was invited to exhibit at the 1889 Expo, which is how King Cophetua arrived in Paris and Burne-Jones was awarded the Legion d’honneur, a gold medal from the Expo jury, and membership of the Academie des Beaux-Arts. (Laurence des Cars, ‘Edward Burne-Jones and France‘, p.10-11) Khnopff himself exhibited at the Exposition (Memories), and must have been struck almost as much by the aedicular frame of Cophetua as by the monumental painting.

Burne-Jones (1833-98), King Cophetua & the beggar-maid, 1884, o/c, 293.4 x 135.9 cm., Tate

*

Lot 11 William Degouve de Nuncques (1867-1935), Paysage de neige, pastel on blue paper, 22 cm. diam., in a frame of metal, wood and leather

William Degouve de Nuncques wasn’t formally trained as an artist, having left the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Brussels before graduating; but he met Jan Toorop as a teenager, and although there was a difference of nine years between them, he became very friendly with the older painter, eventually sharing a studio with him. Toorop’s idiosyncratic frame designs, as much as his technique and style, may have awakened him to the importance of the setting in the whole work of art – or possibly this may even have been a mutual awakening which they shared, since Toorop’s best-known frame designs date from 1893 and 1898.

William Degouve de Nuncques (1867-1935), The Manacor Grotto, Mallorca, c.1901, gouache on paper, 37 x 52 cm., ex-Patrick Derom Gallery, Brussels

Degouve de Nuncques’s frames are also quite different from Toorop’s; they do not integrate the border into the image, but create a striking silhouette which draws the attention, focuses the eye and harmonizes with the pictorial form, whilst the façade of the frame provides an area for motifs which may reflect compositional shapes and lines. He belonged to Les XX, which included other artists concerned with providing frames for their work which illuminated and expanded it symbolically, harmonized or created visual tension with it, or extended it through colour or tone into its surroundings. Van Rysselberghe, Finch, Georges Lemmen, Henry van der Velde and Toorop were amongst these, and others who exhibited with them included Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, Seurat, Signac, Whistler and Van Gogh.

None of them, however, produced frames quite so radical as that of Lot 11 – its horizontal oval form opposed to the circular pastel, its top and sight mouldings of metal, and its ornament (which echoes the shapes made by the painted branches) formed by a cut-out leather overlay on the frieze. None of them, either, would have designed something which – from hindsight – looks so much like a very early instance of an art deco object as the trapezoid-ish oak frame of the Manacor Grotto, above.

*

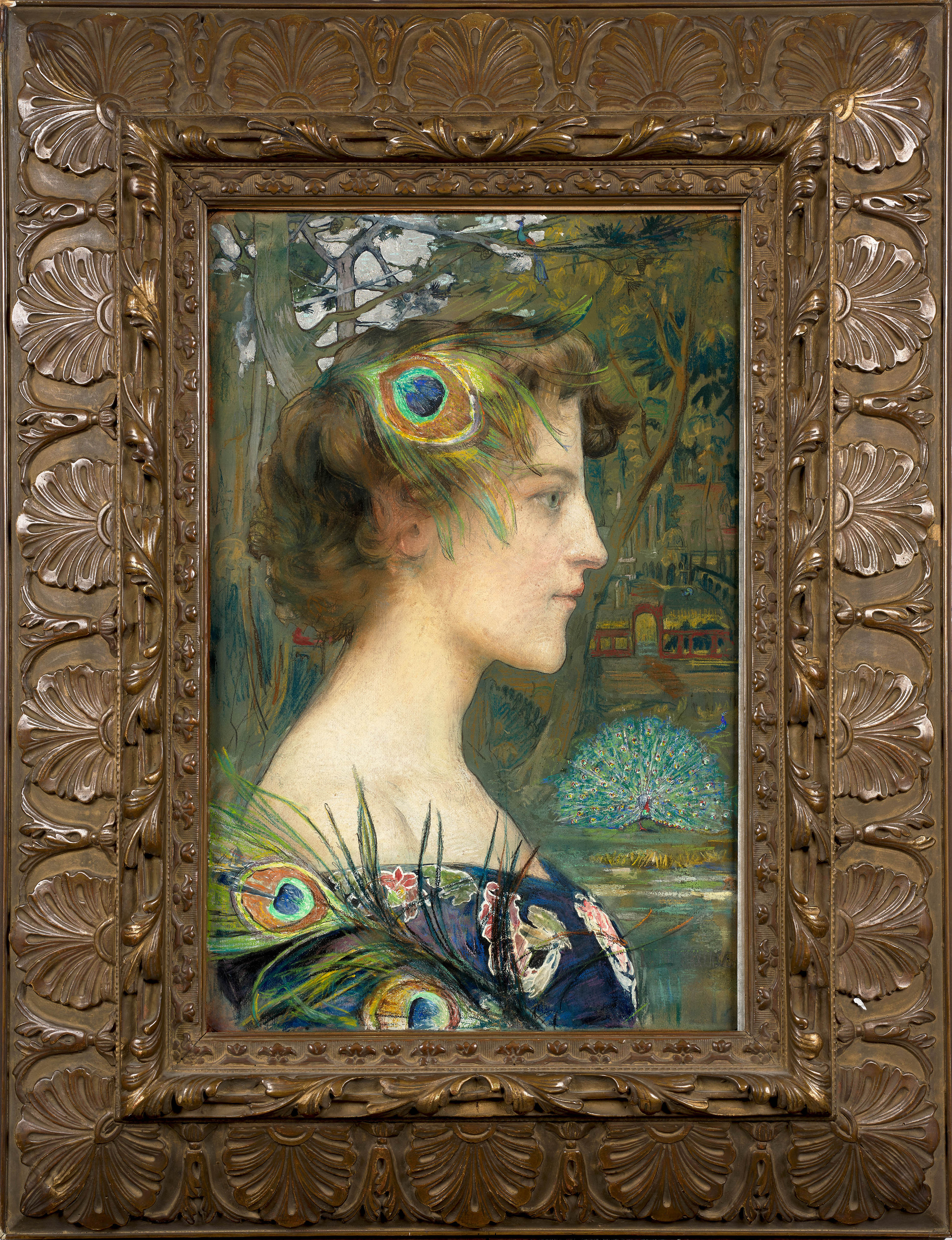

Lot 13, Edgard Maxence (1871-1954), Profil au paon, 1896, pastel and gouache with silver on paper, mounted on canvas, 31 x 47 cm., in the original artist’s frame

Edgard Maxence trained first in the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Nantes, and then in Paris, eventually becoming a student of Gustave Moreau. Moreau’s biblical and mythological subjects, as well as his Symbolist style (established very early), were all of influence on Maxence, and it is certain that his framing choices were equally important.

Gustave Moreau (1826-98), Les licornes, no date, 115 x 90 cm., Musée Gustave Moreau

Moreau’s dream of visual richness was matched by his settings, which can be either aedicular or rectilinear, but in both cases have multiple ornaments or other enrichments. The peacock feather pattern which frames Maxence’s peacock girl appears on Moreau’s unicorn girls, and has been used (probably after the latter’s death) to frame his self-portrait, also in the Musée Gustave Moreau. For each artist this was a promising symbol; the peacock stands for immortality and resurrection, and is also an attribute of Hera, queen of Olympus and bride of Zeus. Both works are otherworldly, but where Moreau has realized the mediaeval Dame au licorne tapestries as a chivalric Arthurian landscape, set in its eternal garland of peacock feathers, Maxence has imagined a mysterious Renaissance garden where the spirit of the place can take human form but still wears her signifying feathers, repeated on the frame.

Edgard Maxence (1871-1954), Femme à l’orchidée, 1900, o/c, 59 x 45.4 cm., Musée d’Orsay

Maxence exhibited in the Salons de la Rose+Croix from 1895 to 1897, and also in the 1900 Exposition Universelle, where his Fleurs du lac won a gold medal; this was the same year in which he painted (but seems not to have exhibited) the painting above. It is closely related to the Profil au paon in that both are otherworldly figures – a dryad and a mediaeval princess, both posed in close-up against a mysterious tree-haunted landscape, both set in richly ornamented frames which seem to support and echo their worlds, and to suggest further meanings in them. The peacock girl, however, isn’t (like the orchid woman) smoking, however symbolically, a cigarette…

*

Lot 32 Paul Andrez, otherwise Vlaho Bukovac (1855-1922), La belle au kimono, 1890, trompe-l’œil with integral painted frame, o/c, 92 x 73 cm.

Paul Andrez was the nom de pinceau of Vlaho Bukovac, a Croatian who used other aliases (including the Italian Biagio Faggioni, which was apparently his birth name) in order to sell his work. He had trained with Alexandre Cabanel at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and later became an important teacher himself in Croatia, diffusing elements of Symbolism, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, and eventually being appointed associate professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. He had a wide and eclectic range, producing society and state portraits, architectural murals in prominent buildings in Zagreb, mythological scenes, chocolate-box pictures and Symbolist landscapes, as well as several of these trompe l’oeil figure paintings which play with the idea of the sitter breaking the bonds of the frame.

Paul Andrez (1855-1922), Fantasie, o/c, 72.5 x 92 cm., Art Salon Zagreb, 21 December 2017, Lot 9

Paul Andrez (1855-1922), Femme à la japonaise, o/c, 92.1 x 73 cm., Christie’s NewYork, 28 October 1998, Lot 51

These are not new conceits; Rembrandt painted two portraits in 1641 (now in Warsaw and the Royal Collection) in which the figure holds onto an integral painted ebony moulding, thus causing a severe headache for all those involved in producing physical frames to contain them.

Pere Borrell (1835-1910), Two girls laughing, 1880, o/c, 69 x 69 cm., Museu del Modernisme Català

In the 19th century the Spanish painter Pere Borrell del Caso, who was twenty years older than Paul Andrez, produced the well-known image of a small boy climbing right through a picture frame (Escaping criticism, 1874), as well as the portrait above of two small girls treating a tondo frame as a porthole window from which they can assess the looks and attributes of the spectators.

Paul Andrez (1855-1922), La belle au kimono (Lot 32) in its outer, physical frame

*

Lot 67 Pinckney Marcius-Simons (1867-1909), Lohengrin, o/panel, 17 x 22 cm., in an integral painted frame

Rather like John Singer Sargent, the American painter Marcius-Simons grew up and trained in Europe, exhibiting his work at the age of twenty-four (at first very much in an academic and finished style) in both the Salon and the Royal Academy. Soon after this, his style began to change to a visionary Symbolism, accompanied by frames which magnified and expanded on the paintings they were designed for (Le chant du cygne, 1893).

The Artcurial catalogue describes Lot 67 as having ‘a feigned frame, arched at the top’, but, given the elaboration of many of the artist’s frames, and their designs patently each intended for one specific work, it seems more likely that this panel has been painted with its own margin or sight edge (making the arched top easier to accommodate in a rectilinear frame). It would then probably have been held in an outer giltwood setting which would have reflected the Arthurian origins of Lohengrin’s story as a Grail Knight who travelled in a boat drawn by swans.

Pinckney Marcius-Simons (1867-1909), La legend de Niebelungen: Les Nornes, by 1909, o/c, 54 x 72 cm., Maison Verneuil, Paris, 29 October 2021, Lot 78

Pinckney Marcius-Simons (1867-1909), Le Renaissance, o/c, 30.25 x 20.75 ins (overall with frame), Fontaine’s Auctions, Pittsfield, US, 29 May 2021, Lot 628

Both the paintings above have frames tailored to their subjects: The Norns (the Norse equivalent of the Greek Fates) in a northern-ish aedicular setting, and a personification of the Renaissance in a sort of gilded Italianate ceiling panel.

Pinckney Marcius-Simons (1867-1909), Where light & shadow meet, c.1885-1904, and hanging in Sagamore Hill National Historical Site, Oyster Bay, US

Where light & shadow meet was acquired, presumably directly from the artist, by Theodore Roosevelt, who was a great admirer of Marcius-Simons and his landscapes, such as this one, bathed in an unearthly light. It has hung in Roosevelt’s house ever since, along with the other original furnishings, and its frame reveals either that the artist created an American version of his usual designs, or that the patron may have collaborated in some way. Its very specificity, for a landscape which isn’t in itself American, is further evidence for Lohengrin having originally possessed its own specific frame.

****************************

The e-catalogue for the sale of Gérard Lévy’s collection of Symbolist works (11 February 2025) is here.

****************************