Bordercore: Why frames became the new frontier in contemporary art

by Katie White

This article was first published on Artnet (News) on 3 April 2025, and is republished here with the permission of the author.

For a century, the frame was meant to disappear. Today, it’s a site of rebellion, narrative, and physical presence.

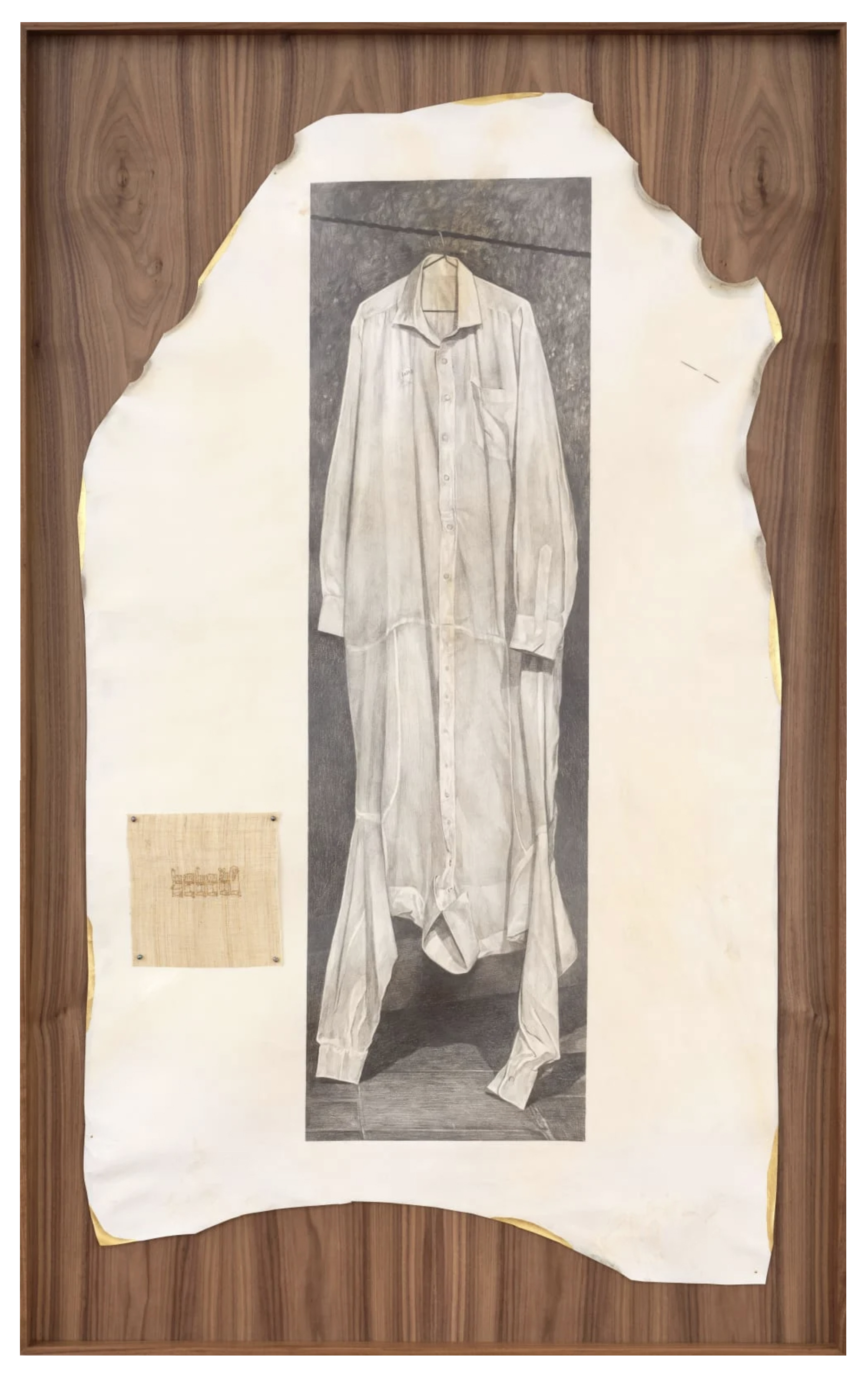

Years ago, the artist Harry Gould Harvey IV came across a fallen black walnut tree in a friend’s yard. He experienced a moment of revelation and felt a sudden urge to make a frame for his drawings from the dying tree.

Harry Gould Harvey IV, Correspondence Radiator / Correspondence Resonator (Asteraceae), 2025, xerox, xerox transfer, coloured pencil, charcoal, black walnut wood, 91.4 x 78.1 x 7.6 cm. Courtesy of Harry Gould Harvey IV and P·P·O·W, New York © Harry Gould Harvey IV. Photo: JSP Art Photography

‘It defined my practice pretty starkly,’ recalled Harvey, who is known for his Gothic-inspired frames, akin to polyptychs. After years of working as a professional photographer, Harvey, who is now represented by P.P.O.W., had turned to drawing as a more intimate form of expression. But he’d felt that something was missing. In building frames based on the world around him, he tapped into an atavistic connection to Fall River, Massachusetts, where he was born and raised.

‘Working with found wood which has a specific provenance to a location and a certain history, and carving it into frames, became a way to contextualize the drawings with the value of place,’ he said. Harvey is one of many contemporary artists who are choosing or creating borders for their works which push against the understated, unobtrusive frames which have dominated exhibition spaces for over a century. These artists are reclaiming the frame, not only as a boundary but as an extension of the artwork itself – a vessel for narrative, memory, and material resonance, drawing on the depths of art history in new ways.

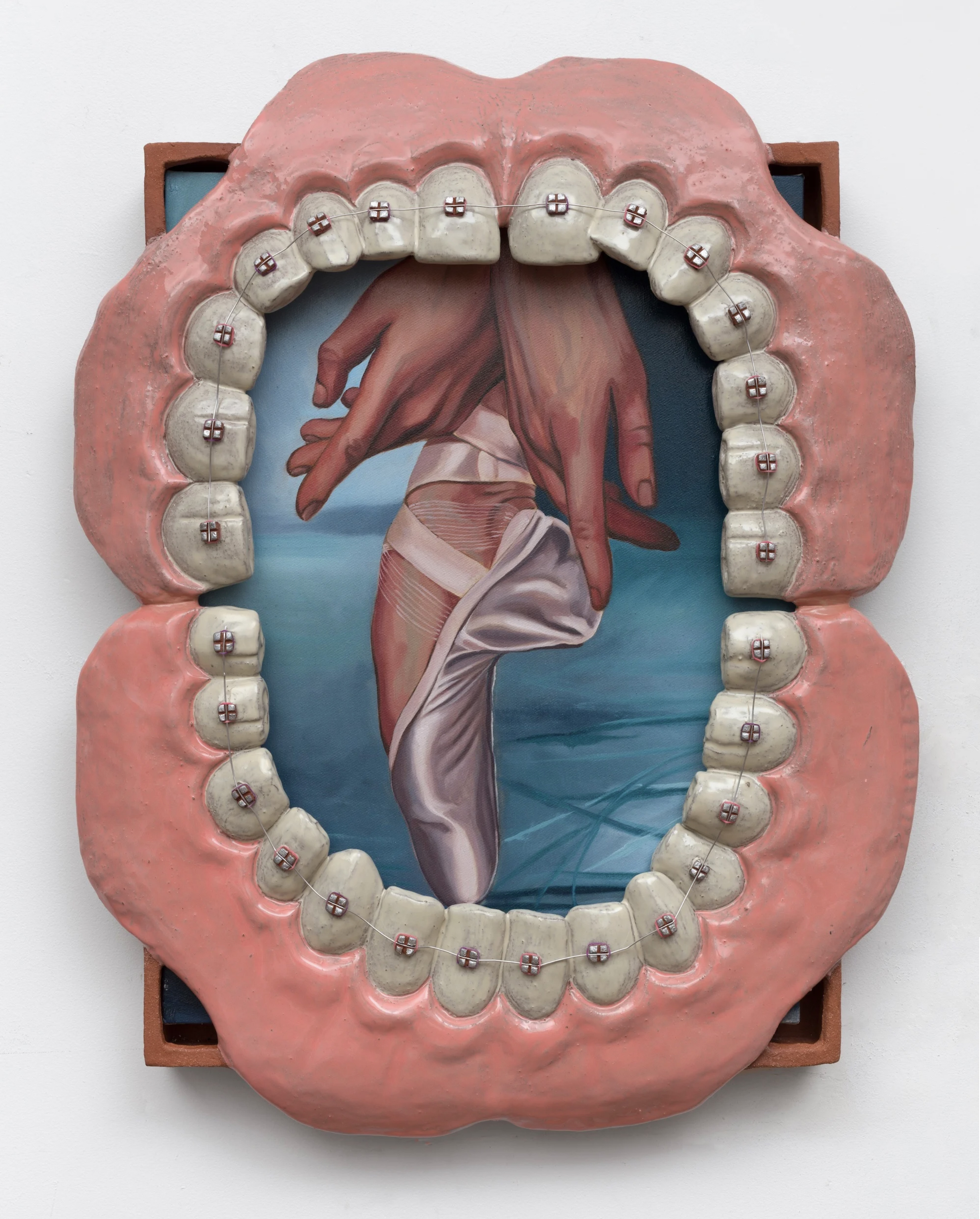

Jenna Rothstein, Nude, 2024, acrylic on wood, ceramic, 22.9 x 27.9 x 2.5 cm., Harsh Collective, Brooklyn

The art advisor Emily Sussman pointed out this tendency recently in her Substack, Métier. Sussman noted that artists are using frames as an extension of the work, writing that these are ‘a far cry from the ornate frames hanging around works in places like the Met, or the modernist and sleek frames found in contemporary stores (and chains like Framebridge) that certainly don’t distract nor detract from the art within’. She mentioned the work of artists such as Emma Kohlmann, Larissa Lockshin, Jenna Rothstein, and Stephanie Hemma Tier as emblematic of this trend. In Rothstein’s work, for instance, small-scale paintings on canvas are surrounded by frames of ceramic spiky teeth-like thorns or faux multi-colour mosaics.

Meanwhile, a long-overlooked pioneer of contemporary framing recently received some overdue institutional accolades. Last fall, the New Museum Los Gatos, near San Jose, featured a solo exhibition of works by Holly Lane , a Californian artist who bucked the unwritten rule to keep frames minimalistic back in the 1980s. Lane instead carved her own elaborate wooden frames which hearkened back to the Renaissance.

Holly Lane, Wading through amber, 2020, acrylic and carved wood, 12 ½ x 17 ½ x 4 ½ ins.

‘At that time, if a painting had a frame at all, it was a thin strip, serving as protection for the art, and as a conceptual dividing line,’ Lane recalled. ‘A good frame was an inconspicuous one. If I made the frame itself art, which was conspicuous and relevant to the painting, then I could erode that sense of a border and posit that art has no borders, especially to our mind and soul.’

Frames are finally back in the spotlight – call it bordercore. A new wave of contemporary art is reconsidering the frame as a central character, one that is surreal, sculptural, and symbolic. Artists are using the border not just to contain, but to comment on, disrupt, or extend the work beyond itself. This is driven by the embracing of more bespoke, historic artistic processes, but also serves as a rebuttal to the superflat virtual age. More and more, paintings have been appearing at fairs and in exhibitions with statement frames, after a long era of often frameless display. If, for previous generations, the frame was a liability which could detract from the cerebral, intellectual, and aesthetic experience of the canvas, artists today are creating frames which attempt to pull us back into bodily reality, a haptic experience of art.

But first, a brief history of framing

Before we dive into the current fascination with frames, what do we need to know about their history? Where did those ubiquitous little black – or white – frames come from, anyway?

Jan van Eyck (c.1390-1441), Portrait of a man (Self-portrait?), 1433, o/c, 26 x 19 cm., National Gallery

Believe it or not, frames have been a hot topic for centuries. The concept of a frame as it is known today – a removable object around a work of art – has its roots in the 15th century, roughly coinciding with the rise of secular genres of European art (though framing devices date back to Greco-Roman times, too). But the question of whether the frame was part of a work of art, an accent to it, or a potential distraction from creative genius, has been a tempestuous topic of debate among philosophers from Immanuel Kant to Jacques Derrida (Kant said frames were decidedly not art; Derrida didn’t exactly agree).

Sure enough, frames metamorphosed over the eras (art historian Lynn Roberts has independently recorded a history of frames on her website The Frame Blog, an invaluable resource on this myopically overlooked topic). Ornamental gilded frames, still so often seen in museums, were becoming ubiquitous throughout Europe from the Renaissance onwards. By the 19th century, with the dawn of industrialization, frames which had previously been carved by hand gave way to versions assembled from moulds and made of plaster or composition. With this standardization, the innovations and artistry of framemakers waned, and frames became increasingly mass-produced. And once the Paris Salon had insisted upon gilded, rectangular frames for hanging submissions, the outlook was bleak.

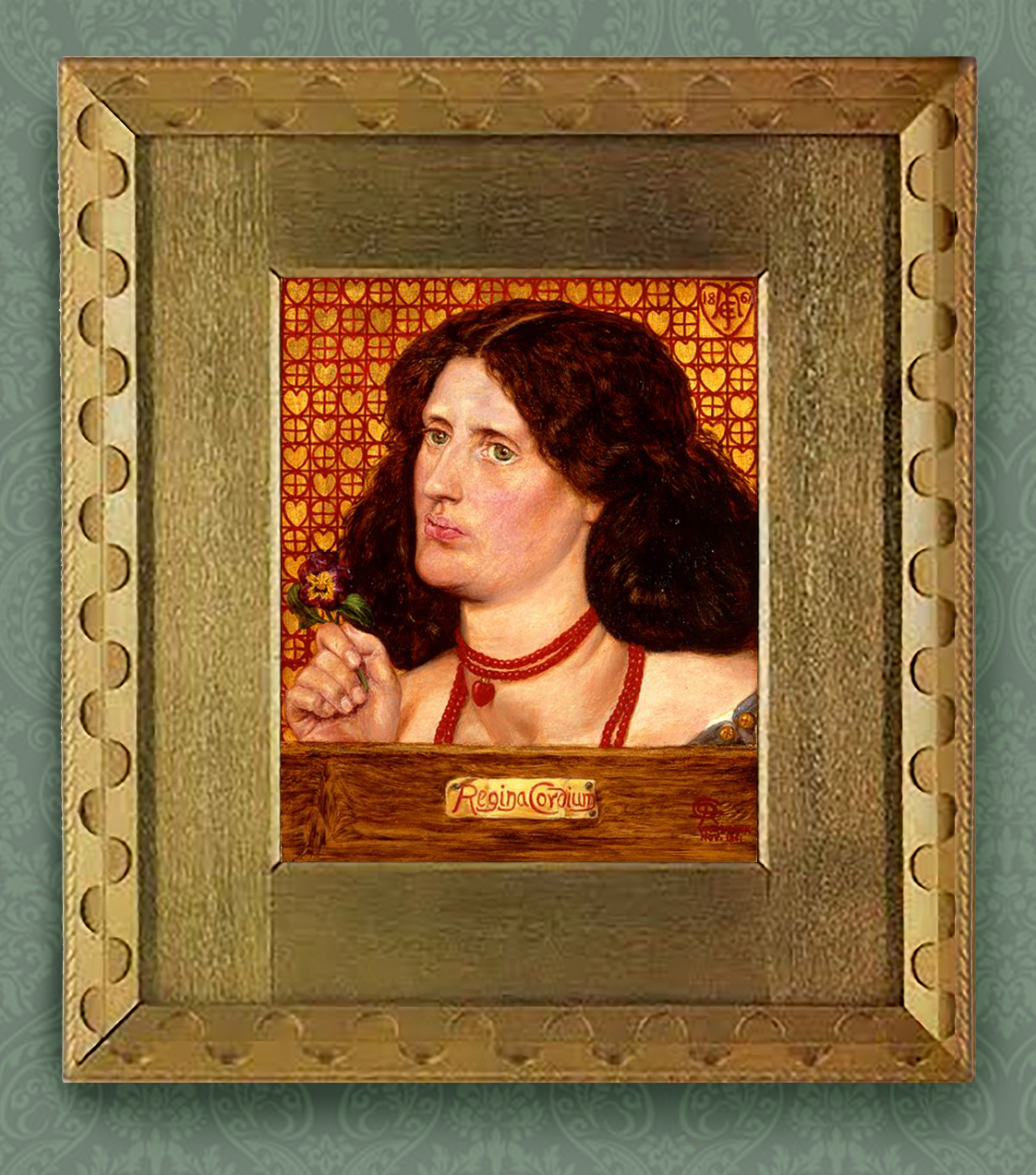

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Regina cordium, 1861, private collection

However, and also in the 19th century, artists began to rebel – notably the Nazarenes in Germany and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in Britain, many of whom – like Rossetti, above – created unique frames for their works.

The Impressionists built on this momentum and thrust frames into modernity with insouciant gusto. In 1877, Pissarro and Degas pioneered works at the Salon in scandalizing simple white architrave frames. The decision was partially born from reasons of economy – these artists were poor. Still, it’s probable that they were also inspired, in part, by the teachings of colour theorist Eugene Chevreul, who believed that a white foil heightened the effect of other hues.

Degas (1834-1917), Dancer au repos, 1879, pastel & gouache on paper, 59 x 64 cm., in original ‘pipe’ profile frame, private collection. Photo: Jed Bark

Critics soon began to comment on the archetypal white frame as we know it today. Things were just kicking off, however, and as Modernism gained ascendancy in the 20th century, frames continued to become more and more streamlined. The canvas was a supreme and transcendent place of contemplation, and frames, in this view, were best banished to the background whilst the art took the spotlight.

For a while, the measures to make frames invisible reached a near-comic peak. In the mid-century, ‘frameless’ hanging techniques were popularized, encouraged by the introduction of the Bildträger, or clip frame [1]. For a generation of Modernists, these framing devices offered the quasi-philosophical fulfilment of art presented as boundless, seemingly floating in space. Still, there were moments of controversy: a 1949 exhibition of Giovanni Bellini’s work at the Palazzo Ducale, in Venice, under the direction of celebrated architect Carlo Scarpa, displayed the Renaissance masterpieces without any frames, rather than in replicas of historic styles, to the delight of some and dismay of others.

Frida Kahlo, Diego and Frida 1929–1944, 1944 , oil on masonite with original painted shell frame, private collection, Courtesy Galería Arvil. © 2021 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; via Dallas Museum of Art

But even during this nadir for the frame, many artists still embraced it. Wassily Kandinsky, Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Florine Stettheimer and many others, designed, purchased, built, and painted unique frames for their works.

Reframing history – and the present

For some contemporary artists, the historical significance of the frame is front of mind. Amongst these is New York City artist Valerie Hegarty who creates multi-media sculptural works which look as though centuries-old paintings – and their frames – have endured cataclysmic elements and the ruinous effects of time. She makes these works using a motley assortment of materials including wood, canvas, wire, air-dry clay, foil, tape, epoxy, acrylics, foam core, thread, paper, and more.

Valerie Hegarty, Niagara Falls, 2007, foamcore, paper, paint, wood, glue, gel medium, 150 x 300 x 65 cm. Courtesy of the artist

Hegarty’s works often reprise heroic landscape paintings such as those of the Hudson River School – but with a post-apocalyptic twist. A 2007 work, for instance, reimagines Albert Bierstadt’s 1869 painting Niagara Falls; in Hegarty’s work, the painting is torn, its frame twisted and charred, and everything spills downward from the wall toward the ground.

‘I grew up in a house filled with Americana and early knock-offs of American landscape paintings. This idea of Manifest Destiny, virgin wilderness, and American identity is so tied to landscape painting,’ Hegarty explained in conversation. ‘To me, in a museum, a frame meant the narrative was set. That this was truth. Breaking the frame is questioning the narrative, exploding the narrative, or suggesting that there is something wrong with it.’

Valerie Hegarty, Fallen Bierstadt, 2007, foamcore, paint, paper, glue, gel medium, canvas, wire, wood, wall piece: 177.8 x 127 x 42.5 cm., floor piece: 7.6 x 100.3 x 25.4 cm., Brooklyn Museum

By disrupting the frame, she attempts to pull viewers into conversation and into the timeline of history itself. Her work Fallen Bierstadt in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum has often stopped visitors in their tracks to ask what has happened to the work.

‘There’s this idea that the paintings are timeless when they’re framed. The bigger the frame, the more important the narrative. When you are making the painting decay, it’s questioning that idea of timelessness or the truth of the narrative, but also referencing the materials and maintenance that goes into keeping these paintings in pristine shape,’ she added.

Kang Seung Lee, Untitled (Constellation), 2023, on the ground, with works by Romany Eveleigh on the wall behind. Photo by Ben Davis

Kang Seung Lee, who is represented by Alexander Gray Associates, designs frames made from a variety of burred woods which also engage with history. At times, these frames are positioned horizontally, on the ground, as with his installation Untitled (Constellation), which was on view at the 60th Venice Biennale last year, and which shifts the perception, physically.

‘In some ways, the work resembles mood or vision boards mediating the juxtaposition of information and context,’ he explained. ‘To me, it was like creating a fertile ground.’

This installation, like many of Lee’s works, examines queer histories across many geographical locations, countries, and continents, offering a diffuse rather than didactic approach to history, and welcoming into the fold stories which have long been kept on history’s margins.

The sacred and the surreal

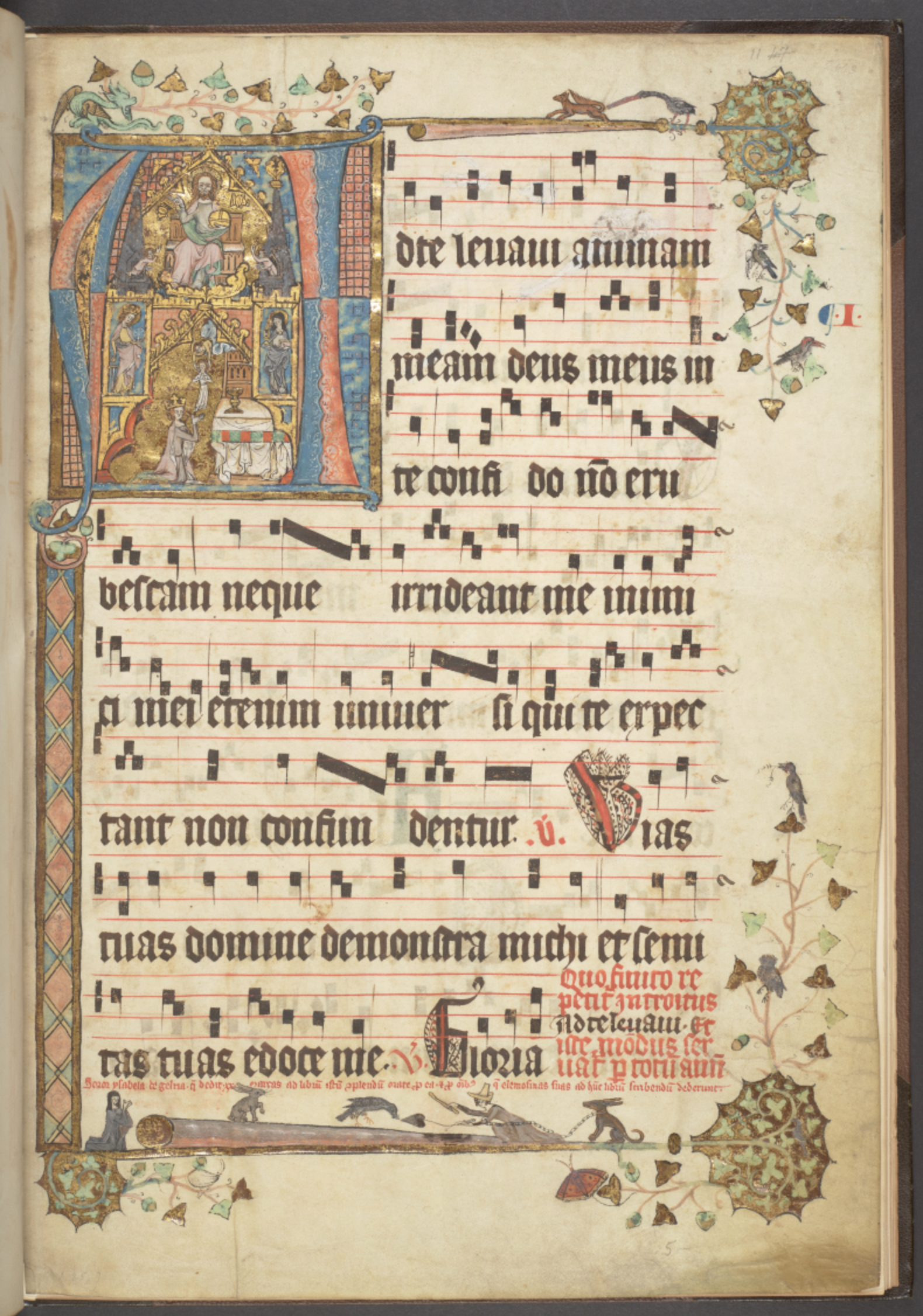

What can the mediaeval marginalia of illuminated manuscripts – books with painted decoration which includes precious metals such as gold or silver – tell us about our current moment of inspired and even outlandish framing? It’s an unexpected question, but a fruitful one. For artist Holly Lane, the bawdy and beatific doodles in mediaeval manuscripts sparked her frame-building journey. As a student at San Jose State University in the mid-1980s, she came across illuminated manuscripts in the library and was mesmerized by the way that the scrolling borders commented visually on the text.

Opening leaf from a Gradual: Add MS 35069, f. 11r, British Library; MS written & illuminated for the Convent of St Clare, Cologne

‘Sometimes the borders had naughty creatures spoofing the text, even mooning the text – that was my moment of epiphany,’ Lane said. ‘I realized that a frame could be many things; it could be a commentary, an informing context, it could extend movement, it could be a conceptual or formal elaboration, it could embody ancillary ideas, it could be a shelter, it could be an environment, it could be like a body which houses and expresses the mind, and many other rich permutations.’

Holly Lane, Companions: The three Graces, 2021, acrylic & carved wood, 24 x 16 1/4 x 7 ¾ ins, private collection

She began to build frames which fused with the painting, at times even including doors which opened and closed over her paintings – often German Romantic-inspired landscapes.

‘I envision the frames not as a border, but as a conceptual and formal elaboration, embodying ancillary ideas, setting up pattern rhythms, extending movement, shape rhyming, enshrining,’ said Lane [2].

Stephanie Temma Hier, Hide and seek, 2022, o/linen with glazed stoneware sculpture, 240 x 215 x 20 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Vacancy

Frames and paintings form a similarly symbiotic, elaborative relationship in the work of Brooklyn-based ceramicist Stephanie Temma Hier. Her delightfully decadent works marry surrealistic, sculptural ceramic frames – a toothy mouth, molluscs, bunches of carrots – with startlingly juxtaposed oil paintings – men wrestling, en pointe ballet slippers, and bountiful heaps of food. Not unlike manuscript marginalia, her ceramic frames form associative games with the paintings inside them.

CARO, Is it the same for you?, 2023-24, sterling silver, brass, organza, beads, crystals, pearls, opals, quartz, tourmaline, 12.25 x 8.5” x 1.25 in. Courtesy of the artist/Sarah Brook Gallery

Meanwhile, the London- and New York-based multimedia artist CARO has also reinterpreted illuminated manuscripts. Several years ago, the artist, who is trained in jewellery production, was mulling over the boundaries between art and craft and experimenting with merging embroidery and metalwork.

CARO, Duin, 2019, brass, organza, thread, sequins, beads, 6 x 8.5 x 2 ins, Sarah Brook Gallery

‘I felt like what was keeping embroidery back from acceptance in the art world was the hoop, the circular frame. I thought that if I can make a rectangle, I can show my work as though it is a painting,’ she explained. ‘In making these works, I was inspired by illuminated manuscripts.’

Almendra Bertoni, I think I’ve been healing, 2024, acrylic on canvas with wooden frame, 165 x 114 cm. Courtesy of the artist

The New York artist Almendra Bertoni combines aspects of the sacred and the surreal with a wink in her colourful works. Despite the hyper-modern sleekness of her aesthetic, she works with wooden panels for her compositions and frames – a material often associated with religious works of the past centuries. Grappling with themes of femininity, rage, and sexual and religious taboos, her frames, which she cuts and paints herself, have taken the forms of oversized ribbons or balloon-like flowers.

More recently, however, she’s embraced quasi-Catholic imagery, her frames echoing the shapes of praying hands, doves, and serpents. The artist, who was born in Buenos Aires and raised in Miami, acknowledges the influence of both Renaissance art and contemporary churches.

‘In my work, these religious themes are a way of challenging doctrine, but also thinking about devotion in a respectful way,’ said Bertoni. But her works, with their trompe l’oeil frames, also nod to Surrealism, and artists such as Salvador Dali, Frida Kahlo, and Leonor Fini. Bold, bright frames can, Bertoni added, ‘serve as a way of reaching the otherworldly, of breaking the bounds of that square canvas.’

Bold frames in a flattened age

If the myriad contemporary artists using innovatory frames had a rallying cry, it might be: Joy in materiality!

For some, the material makeup of their frames holds a potent significance. Harvey, the artist who made a frame with a fallen black walnut tree, describes his frames as a ‘provenance, almost a ready-made setting’. For a recent project at Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum, he made frames from wood cut down on the land of the Delano family in Massachusetts, who, he said, were amongst the most successful opium smugglers, and the grandparents of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. ‘Showing frames carved with this wood is a direct, economic, cultural, and linguistic invocation, and allowed me to bridge that history to now,’ said Harvey.

Kang Seung Lee, Untitled (Lazaro, Jose Leonilson 1993), 2023, graphite, antique 24 carat gold thread, Sambe, pearls, needle, 24 carat gold leaf, brass nails, goatskin parchment, 137.1 x 82.5 cm., MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo), Brazil. Photo: Paul Salveson

Kang Seung Lee’s frames hold similar material resonance. In a recent series called In skin, Lee looked to aging queer bodies as both living personal and political archives, and sourced wood for his frames which would reflect a dendrochronological approach, using maple, olive tree, redwood, and walnut, obtained mostly from naturally fallen trees on the West Coast.

For other artists, such as Alicia Adamerovich of Timothy Taylor Gallery, who has made unique wooden frames for her biomorphic drawings, creating frames was a chance to make frames as sincerely curious as the drawings themselves.

Alicia Adamerovich, Butterfly, 2020

‘The hectic nature of everything we consume on a daily basis pushes some artists to drift towards making repetitive, super cohesive, and almost branded work,’ she said, ‘For me, it caused a desire to make things that jump around in some way, either aesthetically or conceptually.’

Brooklyn ceramicist Stephanie Temma Hier believes that the physicality of her frames resists the all-permeating, flattening aesthetic afoot in today’s culture. She no longer sees her frames and paintings as being distinct from each other. Instead, through their unexpected union, these hybrid artworks jolt viewers back into the material world.

Stephanie Temma Hier, Cat’s cradle, 2022, o/linen with glazed stoneware sculpture, 78.74 x 60.96 x 8.89 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Bradley Ertaskiran Gallery

‘Paintings are not just images, they are made from pigments, fabrics, wood, and metal,’ she explained. ‘Even the Modernists were obsessed with the thickness of the paint and how that contributed to the feeling of the image. Now paintings are so often flattened by the photographs that represent them, that we can forget that the objects possess a real presence. Yet somehow when a painting is framed by a sculptural, non-rectangular frame, this can reanimate its presence on the wall.’

Bertoni, meanwhile, put it succinctly: ‘I think about algorithms and how our attention spans are just so shortened now that you want to experiment in ways to get people to stop scrolling.’

But, for these artists, it’s not just the art lovers who need to take a moment – the artists do, too. CARO, who is studying jewellery techniques known by a dwindling handful of aging artisans, sees her labour-intensive works as a visual speed bump.

‘The belief is that forward is always better,’ she said. ‘I’m a bit of a contrarian, but there’s so much to be said for slowness. We can learn a lot by studying history. Progress isn’t always linear. I always try to prize methods of working that are aligned with a slower pace, circadian, at the pace of the body and the natural world.’

Holly Lane, The mooring hour, when sky is nearer than skin, 2009, acrylic & carved wood, 23 ½ x 25 x 7 ¾ ins, private collection

An early adopter of intricate frames, Holly Lane aims to engage both the mental and visual experiences of art.

‘I see pictorial space as mind space, as we must project our minds into the painting,’ she said. ‘While the spatial qualities of [a sculptural frame] exist in our own physical space, we walk around it, proportion our bodies to it – so in part, [it] is apprehended or “seen” by the body.’

In this way, bold frames try, however fleetingly, to pull our minds back into the experience of our bodies.

************************************************

[1] See ‘Frameless art, boundless Modernism: the clip frame‘

[2] See, too, Steve Shriver’s interview with Holly Lane on The Frame Blog: ‘Borderlands‘