Giulio Licinio’s Pietà with mourning angels reunited with its frame

by Paul-Bernhard Eipper, Ulrich Becker, Melitta Schmiedel

In 1571/72, Giulio Licinio[1] painted his Pietà with mourning angels [2] for the altar of the new court chapel in the west wing of the castle of Graz, where it was given a particularly splendid decorative frame. The painting is listed in the first inventory of the Landesbildergalerie (the predecessor of the Alte Galerie, which now houses the collection in Schloss Eggenberg), with the date of reception as 10 June 1819. The owner at this point was the ‘k. k. Prov. Baudirection’.

The painting was removed from its altar in 1819, probably because the chapel was already in a poor state of repair at the time, and remained in the Landesbildergalerie until 1838. It is documented there in the second inventory, in which acquisitions and movements of objects up to 1838 were recorded [3]. The old inventory number of the Styrian Landesbildergalerie is now no longer recognizable – if it was ever fixed to the painting at all; perhaps it remains, underneath the second lining which was added in 1882.

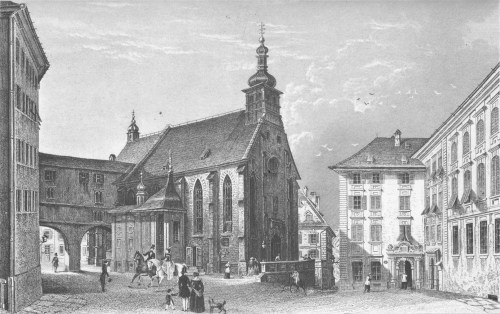

Schlossberg Graz before the demolition of the old castle (completed in 1854); illustrated in 1809: Die Letzte Festung (The last fortress), by Stefan Rothbart, 2019

The chapel of the castle was renovated in the 1840s, when the ‘k. k. Prov. Baudirection’, which was responsible for managing the castle premises, is listed as the owner of the painting.

‘When the Governor of Styria, Count von Wickenburg, had the court chapel restored in the 1840s, [the Pietà] was returned to its original location [the court chapel of the Friederician Tract of Graz Castle]. Since the demolition of the Friederician Tract and the chapel in 1853, it has been leaning against a wall of the upper court oratory, instead of the Grazer Dombild’.[4]

Conrad Kreuzer (1810-61), Graz Cathedral, from Gustav Schreiner’s Grätz: Ein naturhistorisch-statistisch-topographisches Gemählde dieser Stadt und ihrer Umgebungen, Graz, 1843; reprinted 1976

It is clear, therefore, that after this renovation the painting was replaced on its original altar; however, despite the chapel being repaired, the castle itself was demolished a few years later in 1854, due to its overall poor structural condition. The corridor which connected the castle to the cathedral [the bridge-like structure, seen on the left in the engraving above] was also demolished in the process. The nearest location for a sacred painting such as Licinio‘s Pietà was clearly the Cathedral of Graz, and thus it was moved to a chapel located near to the blocked-off corridor entrance, on one of the upper floors of the north side of the choir loft, where it was not visible to the public. We do not yet know whether the province of Styria had donated this painting to the church. Although such an important work of art for Graz, the painting was next recorded in a neglected state in this side chapel of the cathedral, where it was discovered in 1880 by Josef Wastler[5].

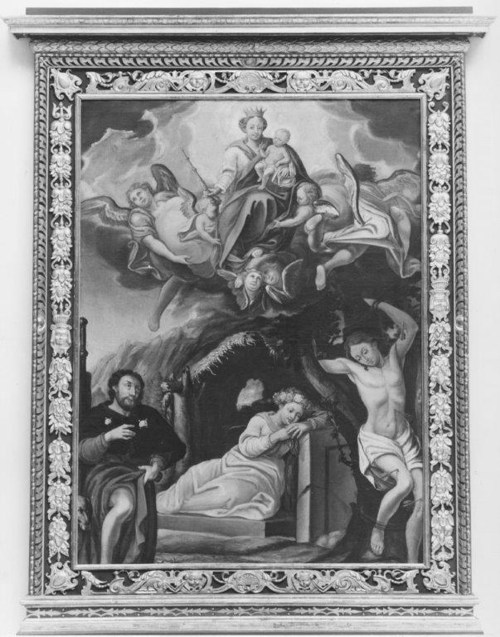

Giulio Licinio (1527-91), Pietà with mourning angels, 1571/72, o/c, 180 x 118 cm., Alte Galerie, Schloss Eggenberg, Graz. Photo: Nicolas Lackner/UMJ

‘I found it two years ago in an abandoned chapel above the court oratory of Graz Cathedral, still adorned with its splendid old Renaissance frame, leaning against the wall. At my suggestion, published in a newspaper, the picture was rescued from its hiding-place, the frame was regilded, and today it hangs on the wall of the south aisle of the aforementioned church.‘ [6]

Monsignore Johannes Graus (1836-1921), Hoforatorium or Friedrichskapelle, Cathedral of Graz; photographed between 1882 and 1921

In 1882, Wastler having arranged for the painting to be moved to the nave of the cathedral, he also had it restored and the frame refurbished in appropriate style. During this restoration – which was more of a reinterpretation – the structure of the frame was altered from its original size, and today measures 258 x 190 x 20 cm. Wastler also seems to have designed an addition in the shape of a swan’s-neck pediment made of scrolling acanthus leaves, which is evidently not there in the earliest image (dating from the 1850s; see below): unless he found some indication of an attachment on top of the cornice.

The altarpiece frame was treated according to the standards of the time: the more nuanced silvering and gilding were completely removed, apart from the most minimal remnants, and the ornaments were taken off the frame, reworked, regilded and then remounted.

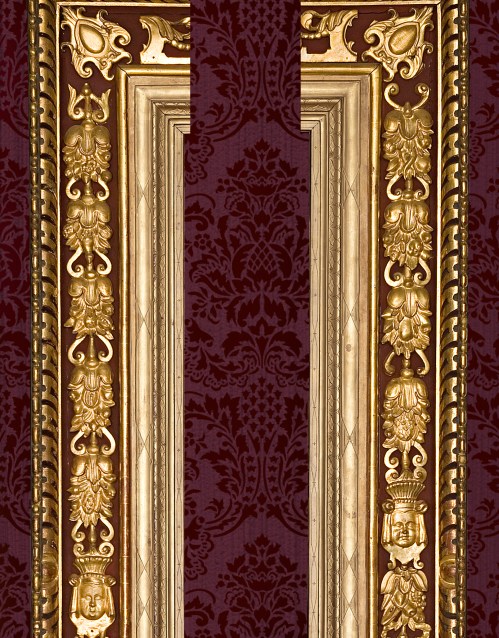

Frame of the Pietà: detail of lateral rails. Photo: Nicolas Lackner/UMJ

This resulted in inconsistencies in the lateral drops which is still noticeable today: the masks at centre left and right are not symmetrical on their horizontal axis, a state which was retained during the renewed – more careful – restoration in 2017 for reasons of authenticity. This would not have happened, had this been a new historicizing frame made at the end of the 19th century.

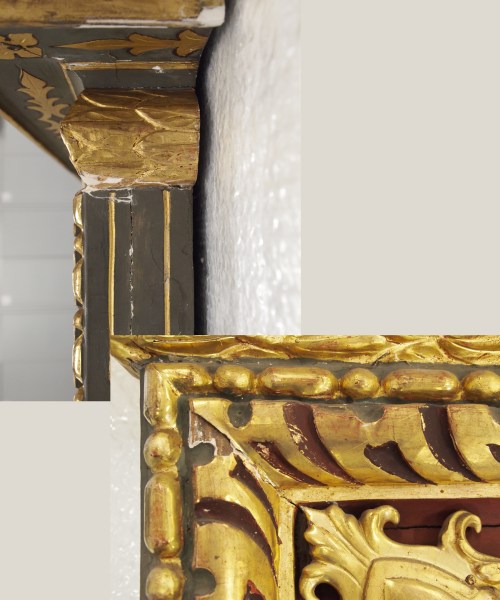

Details of inner moulding of the original frame, with engraved decoration. Photo: Paul-Bernhard Eipper/UMJ

The original inner frame – the only moulding which the painting retained for the next hundred years – was also altered and given new engraved decoration. The restored version, which Wastler instigated, therefore altered the original character of the frame, although it can be assumed that the restorers were working from a knowledge of its original design. However, the resulting tension in the appearance of the frame – what with the asymmetrical centres, the alterations in the ornament and the overall look – led ultimately to doubts as to whether the frame actually dated from the 19th century after all. It is certainly thanks to the ‘care‘ of the 19th century that the original frame has survived at all, but the primitive methods used on it are very much to be regretted.

The painting was also restored during this period. During removal of the varnish, the strong solvents which were used produced serious damage in the paint layer, especially on the upper weave of the canvas, making the ground more visible. At the same, the canvas was given a second lining. The diocesan museum inventory number would probably have been added as part of this process.

Licinio (1527-91), the Pietà with the inner moulding of its original frame, in which it has been displayed in the Alte Galerie since c.1913-18. Photo: Paul-Bernhard Eipper/UMJ

The painting may finally have been separated from its richly decorated aedicular frame before the First World War. Since 1913, the Licinio Pietà, together with its original frame, has been on permanent loan to the Graz Diocesan Museum in the Alte Galerie, and from around that time it has only been displayed in the gallery in the relatively plain inner moulding of the 16th century frame; a complete contrast to the outer frame, which is unique in terms of its size and ornament.

Detail of back edge at top corner of frame and the corrnice above it; with front view of top corner of frame (astragal-&-bead; raking flute; glimpse of frieze with applied ornament). Photos: Melitta Schmiedel/UMJ

Details of lateral centre mask and corner cartouche. Photos: Melitta Schmiedel/UMJ

The outer frame was stored – probably for reasons of space – in very makeshift conditions in a cellar room of the Joanneum building in Neutorgasse, which was newly-constructed at the end of the 19th century. It is also possible that the painting and frame might have been separated during any war-related removals: paintings were generally considered to be more worthy of protection than unwieldy, heavy frames.

The separate storage of frames and pictures was of course common in peacetime, as well, if only for reasons of space, since paintings could be hung more closely on the racks without their frames. This also minimized damage, as the projecting mouldings of the frames no longer collided when the racks were pulled out. Sometimes pictures lost their original frames due to other occurrences: for instance, if the canvases were punctured, they were often relined (the technique of mending tears was not invented until 1945). To do this, they were cut from the stretcher, and in order to be able to restretch them, the edge of the painting itself was encroached upon. This meant, first, that the picture was reduced in size all round, and second, that the old (and often original) frames were then too large, and new ones in contemporary fashion were purchased. Without their paintings, the old frames were less useful, and were either stored separately or straightaway disposed of.

Possible damage to the frames during movement on and off the canvases and separate storage in different depots was accepted, as was the unfortunate fact that the relationship between the painting and the frame would be forgotten. Of course, in the decades after the war – even, perhaps, as late as the new installation of the Alte Galerie in 2005 – it would have been perfectly possible to highlight the Renaissance character of Licinio’s Pietà and its original frame, but by that time there was simply a blank in knowledge of the relationship.

Paintings in the 18th century pattern Dresden gallery frame, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, the Dresdner Zwinger Museum, 2007. Photo: Jorge Royan

It should also be pointed that, in large collections in particular, care has often been taken to standardize frames as far as possible in order to unify a hang, meaning that original frames which stood out became quite rare (see, for example, the gallery frames used in Dresden [7], Düsseldorf, Munich, and Vienna). It is not uncommon today, if a decision is made in favour of reframing a work, for replicas to be specially carved, or antique frames purchased on the art market, both of which can be very expensive. Not least for this reason, some institutions maintain a certain ‘frame diversity‘, such as the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, where, simultaneously with the 2019 exhibition of Netherlandish paintings (Dutch Spring), nine newly-reinstalled rooms of the permanent collection opened, displaying many works which have retained their collectors‘ frames from the 17th to 19th century. The result shows that this blend of settings need not be a disadvantage per se; variatio delectat.

Carl Reichert (1836–1918), The chapel, Schlossberg Graz, 1850s, watercolour, showing Giulio Licinio, Pietà with mourning angels on the altar; courtesy of the Steiermärkisches Landesarchiv, Graz; OBS-Graz-II-F-2-A-5-002

It was thanks to Ulrich Becker that the original frame of the Pietà was able to be reunited with the painting. He discovered that both items belonged together in 2012, on the evidence of a watercolour by Carl Reichert (1836–1918) [8], which shows the court chapel intact, in the west wing of Graz Castle, shortly before it was demolished in 1853.

Outer frame of the Licinio used to display a 17th century Madonna & Child with SS Roch, Sebastian & Rosalia, o/ linen, AG inv. no. 981, Alte Galerie, Graz. Photo: c. 1960s: AG/UMJ

Until 2017, Licinio’s painting hung in the Alte Galerie’s permanent collection in the plain inner frame of the original, which has a black border on the back edge [9], while the outer frame was used, temporarily, to frame a Baroque painting of inferior quality – actually to great effect; this was quite common practice. The reuniting of the Pietà and its frame meant not only that a unique Renaissance frame could be returned to its proper purpose, but also that an important monument of Graz court art from the Counter-Reformation period could be recovered [10]. An exhibition on the Counter-Reformation in the Alte Galerie catalyzed the restoration and reunion of painting and frame, which were displayed together again for the first time in 2017[11].

Details of the carved, parcel-gilt and painted decoration on the back edge of the outer frame, and the engraved ornament on the inner frame, showing how they echo each other; yet is the design of the engraving retrospective? Photo: (above) Melitta Schmiedel/UMJ & (below) Paul-Bernhard Eipper/UMJ

The established museum practice of trying to frame paintings appropriately for their period has a exponentially great effect [12]. This may also be the case when a costly, labour intensive replica has to be used; for instance, with The Sistine Madonna[13] in Dresden, the frame reconstruction there for Franz von Stuck’s Paradise Lost [14], or the new mass framing at the Munch Museum in Oslo.[15]

Of course, the suggestive impression of once again having a ‘properly‘ framed picture in front of you can quickly make you forget that paintings in the frames made specially for them are now the exception, rather than the rule. This makes it all the more significant that the original frame for Giulio Licinio’s Pietà has been identified, and has led to the restoration of the gesamtkunstwerk. The fact that it was altered in the 19th century does not change this, especially as Josef Wastler, who initiated the restoration, must have been guided by the original state and finish of the frame [16]. The Graz case is also of interest in terms of stylistic history: the austere profile is less reminiscent of the late, than of the early, 16th century: i.e., of Raphael’s lifetime, as, for example, the frame of St Cecilia in San Giovanni in Monte, Bologna, demonstrates [17]. We can take pleasure in the fact that the significance of original antique frames[18] is being increasingly recognized, and that those involved – curators, collectors, conservators and dealers – are becoming more aware of them again, rather than seeing them as contemporary, interchangeable fashion accessories [19].

Raking view of bottom right corner of frame, with frieze ornaments, fluted top edge with astragal-&-bead, and narrow ornamented frieze in the plinth. Photo: Melitta Schmiedel/UMJ

Measures implemented

After the condition of the original outer frame of the Pietà had been recorded and documented, the following restoration measures were taken:

A localized consolidation of the frame was carried out using 7–10% sturgeon glue. Lascaux Medium for Consolidation 4176[20] was used locally in the areas of the frame coloured with oil paints. The gluing of the structural frame parts was carried out with cold fish glue (Kremer pigments). Dry cleaning was carried out with hair brushes, microfibre cloths and polyurethane sponges. Damp cleaning was only carried out in the painted areas of the frame, with a solution [0.00025 % Marlipal 1618/25 to 100 ml vitalized water (according to Grander)] using polyvinylformal microporous sponges (‘Blitzfix‘)[21]. Partial post-cleaning was carried out with Shellsol T. Mechanical post-cleaning was carried out locally with a scalpel or acetone cotton swabs and was limited to the partial removal of unaesthetic reworking (oxidized bronzing) or additions. The filling of missing areas/additions to ornaments was carried out with glue and chalk primer, and sealed with shellac. The retouching was carried out with watercolours (Schmincke Horadam) and powdered gold and/or metallic lustre pigments bound in gum arabic to adjust the degree of gloss. The frame rebate was sanded and lined with polyester felt, and new hangers were fitted.

Images taken, during the recent restoration, of the original 16th century timbers at the cornice, and the 19th century reinforcements. Photo: Paul-Bernhard Eipper/UMJ

When the Alte Galerie was rehung in 2019, the altarpiece and its original frame, although not yet displayed on an altar-like base, were once more the focus of the attention they had enjoyed 450 years before.

Giulio Licinio (1527-91), Pietà with mourning angels, 1571/72, displayed, after recent restoration, in the Alte Galerie, Schloss Eggenberg, Graz. Photo: Paul-Bernhard Eipper/UMJ

**************************

Paul-Bernhard Eipper has a PhD from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Witten-Herdecke, and has been Head of Conservation at the Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz, since 2006. He was president of IIC Austria (The International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Österreichische Sektion) from 2013-2017. He is the author of 300 articles and 14 books (on painting techniques, aqueous cleaning of oil paint surfaces, mending of tears in supports). He lectures at Karl-Franzens-Universität, Graz and is Assoc. Prof. for Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Paintings at The Academy of Fine Arts and Design, Bratislava.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks for their support with this article to Dr Peter Wiesflecker (Styrian Provincial Archives, Graz), Christina Kollegger, Nathalie Carina Hammer (Conservation Department, Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz), Dr Christian Müller-Straten (Munich).

**************************

Bibliography

Alte Galerie (Hg.), Zwischen Tanz und Tod: Meisterwerke der Frühen Neuzeit, Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz, 2019, pp. 1–214

Biedermann, G, Gmeiner-Hubel, G., Rabensteiner, C. (Hg.): Bildwerke. Renaissance, Manierismus, Barock: Gemälde und Skulpturen aus der Alten Galerie des Steiermärkischen Landesmuseums Joanneum in Graz. for Kurt Woisetschläger at 70, Geburtstag, Carinthia, Klagenfurt, 1995, pp. 1–265

DaCosta Kaufmann, T, The School of Prague: Painting at the Court of Rudolf II, Chicago/London 1988, pp. 1–336

Eipper, P-B, Konservierung, Restaurierung und präventive Maßnahmen. Gemälde, Skulpturen und Zierrahmen, vol. II, London, 2024, pp. 1–623

Eipper, P-B, ‘Wiedervereint: Gemälde und Rahmen eines Werkes der italienischen Renaissance‘, Museum aktuell, no 260, Dr. C. Müller-Straten, Munich, 2019, pp. 12–17

Eipper, P-B, ‘Zur Bedeutung des Zierrahmens‘, Magazin des Österreichischen Restauratorenverbandes, journal 02, Vienna, 2017, pp. 34–40

Eipper, P-B, ‘Wiederentdeckung eines historischen Rahmens‘, Der Kunsthandel, no 2, Neu-Isenburg, 2017, pp. 29–31

Eipper, P-B (Hg.), Handbuch der Oberflächenreinigung, Dr. C. Müller-Straten, 3, Munich, 2014, pp. 1–493

Eipper, P-B, ‘Reunited: the Graz Pietà in the Alte Galerie is restored to its original frame‘

Hedlund, H P, Johansson, M, ‘Prototypes of Lascaux® Medium for consolidation: Development of a new custom-made polymer dispersion for use in conservation‘, Restauro, no 6, 2005, pp. 432–439

Reichert, K, Kuwasseg, J, et al., Die kaiserliche Burg zu Graz, Graz, 1854, Handschrift, 21 Bll.

Schmitz, T, Lexikon der europäischen Bilderrahmen, vol. I, Von der Renaissance bis zum Klassizismus, Selbstverlag, Solingen, 2003, pp. 1–271

Schuster, U, Verlorenes Graz: Eine Spurensuche im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert nach demolierten Bauwerken und Denkmalen der Steirischen Landeshauptstadt, Österr, Vienna, 1997, pp. 1–166

Stockhammer, A, Artur Rosenauer (Hg.), Geschichte der Bildenden Kunst in Österreich, vol. 3, Spätmittelalter und Renaissance, Prestel, Munich, London & New York, 2003, pp. 1–640

Verougstraete, H, Frames and supports in 15th & 16th century Southern Netherlandish painting, Brussels, 2015, pp. 1–734

Wastler, J, ‘Giulio Licinio, der Neffe Pordenone’s‘, Kunst-Chronik, Beiblatt zur Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, vol. 17, no 23, 1882

Wastler, J, Das Kunstleben am Hofe zu Graz unter den Herzogen von Steiermark den Erzherzogen Karl und Ferdinand, self-published, Graz, 1897, pp. 1–242

**************************

[1] Giulio Licinio (Venice; 1527-91), painter, nephew and pupil of the Ferrarese Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone (1484-1539)

[2] Giulio Licinio, Engelspietà, 1571/72, 180 x 118 cm, oil on two thinly-primed canvases sewn together vertically, AG inv. no. L 23, inscribed below left: IGVLO LICINIO V.F. Outer frame dimensions: 258 x 190 x 20 cm. DaCosta Kaufmann, 1988, p. 218, no. 13.1; Biedermann, 1995, pp. 144, 145; Stockhammer, 2003, p. 508, no. 264

[3] Information provided by Karin Leitner-Ruhe, Christine Rabensteiner, Alte Galerie/UMJ

[4] Josef Wastler, Das Kunstleben am Hofe zu Graz, Graz 1897, p. 35

[5] Josef Wastler (Graz; 1831-99), art historian who studied architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, and in 1858 was appointed professor of geometry, higher geodesy and architectural history at the Technical University in Graz, where he also held the position of rector four times, and was involved in surveying and mapping the city of Graz. As an art historian, specializing in the architecture of the Middle Ages as well as contemporary fine art, he wrote the Steirische Künstler-Lexicon, 1883, which is still in use today. Amongst his numerous reviews and contributions to art history, the following are significant for the present article: Das Kunstleben am Hofe zu Graz unter den Herzogen von Steiermark, den Erzherzogen Karl und Ferdinand (1897); Die Architektur der Steiermark im Mittelalter (1897).

[6] Josef Wastler states that he saw the picture in the frame in the chapel above the Hoforatorium on the north flank of the Graz cathedral choir around 1880, long after the demolition of the castle chapel (1854). Wastler, 1882, pp. 362-364

[7] See Peter Schade, ‘Dresden gallery frames‘, National Portrait Gallery Research programmes: The Art of the Picture Frame

[8] Schuster, 1997, p. 23. The archival record there reads as follows: Inv. no. LA II FZ A 52, although the year of origin is given as 1853.

[9] The rabbet of the outer aedicular frame has an identical black colouring

[10] Becker in Alte Galerie (ed.), 2019, p. 545 ff

[11] Eipper, 2017, pp. 29-31; Eipper 2024, pp. 465–79

[12] See ‘Frame reconstruction in the Bode Museum: more than just an accessory‘ (accessed: 20 May 2019)

[13] See the section on the Sistine Madonna in ‘Presenting the legend: the many frames of Raphael‘. See also also ‘Der Richtige Rahmen für die Sixtinische Madonna’, in Weltkunst (accessed 20 May 2019)

[14] ‘Das Verlorene Paradies und sein Verlorener Rahmen’, Restauro, 21 March 2014 (accessed 20 May 2019)

[15] See ‘Reframing Munch in the light of his original frames‘

[16] A wealth of examples of original frames matched to their paintings can be found on The Frame Blog

[17] Ulrich Becker at the ‘Tag der Restaurierung (Day of Conservation)‘ on 20 March 2017 in the Joanneum Quarter, Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz; see also the section, ‘St Cecilia: vertical aspiration‘, in ‘Presenting the legend: the many frames of Raphael‘

[18] Schmitz, 2003, pp. 1–271; Verougstraete, 2015, pp. 1–734

[19] Eipper, 2017, pp. 34–40; Eipper, 2019, pp. 12–17

[20] The manufacturer does not declare in full the ingredients of the aqueous acrylic copolymer (pH 8.5). Currently, it is assumed to be a copolymer-based vinyl chloride, vinyl acetate and n-butyl acrylate (Acronal 300D, BASF). Furthermore, the fixative contains various additives (3%) such as surfactants, defoamers, fungicides (3%) and solvents (2%). (Glycol ether), its MFT is 4 °C. Despite the undeclared ingredients, in general it is said to have good ageing properties.

[21] According to the Handbuch der Oberflächenreinigung (Handbook of surface cleaning), 5. Aufl., 2015