Italy

15th century Italian drawings

Jacopo Bellini (1396-1470), drawing for a frame with a Lamentation over the dead Christ, Paris drawing book, c.1455-60, pen-&-ink on vellum, 38 x 26 cm., Musée du Louvre

Bartolomeo Sanvito (1433-1511), The triumph of Eternity, for Petrarch’s I Trionfi, c.1480, ink & paint on parchment, Walters Museum

Francesco di Simone Ferrucci (1437-93), design for an altar, 1480-83, pencil, ink, wash, 48.3 x 33.3 cm., V & A

‘Design for an altar with an arched frame decorated with four niches containing saints. Inscribed below the niches in a late 15th century hand, Storia di Sco pieto (top left), Storia di Sco Johans (top right)…

The saints represented are St Peter and St John the Baptist (above); and a bishop, probably St Zenobius, and St Francis (below). Parts of the drawing have been torn away on the right side, and it has been repaired by laying it down on another sheet of paper and drawing in the missing lines. There is a horizontal crease from folding halfway up, and the paper is a good deal stained and foxed all over. ‘

Francesco di Simone Ferrucci (1437-93), design for an altar with an arch framing a ciborium, 1480-83, chalk, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, 15.3 x 22.8 cm., V & A

‘ Design for an altar with an arch framing a ciborium; mounted in a border decorated with trophies, etc., as on Vasari’s mounts… The drawing has been cropped and part of the image lost. Three historic supports have been added. The earliest (foremost) support is a decorated border, parts of which are attempts to restore the lost areas of the original drawing. The drawing and the decorated border were then cropped again, following the curved line of the arch in the drawing. At a later date this has been pasted onto another rectangular support, and the outline of the decorated border restored. The most recent (rearmost) support carries a gold-leaf border of the late eighteenth or nineteenth century…

Vasari’s attribution of this particular drawing to Desiderio da Settignano must have been based on the similarity between the design and Desiderio da Settignano’s work at S.Lorenzo, Florence…

During the medieval period, the Eucharist was stored out of sight. But in the fifteenth century changes in Christian practice meant that it had to be kept on or near the altar for all to see. A new receptacle was required, of a suitably worthy scale and design to house something so sacred. In Italy the new receptacle took the form of a wall-mounted ‘tabernacle’, or a freestanding ‘tempietto.’ For the sculptor this presented a new design challenge, as he tried to incorporate a new and important element into the well-established altar format: if the tabernacle was placed above the centre of the altar, for example, there would be no room for a central devotional image. This is one of a group of drawings made by one sculptor as he tried to resolve such a problem. In it we see the tabernacle forming the centre of the altar, so that only the side niches remain for statues of saints.

Like other sculpture designs from the period, this drawing is most probably by the sculptor himself. The layout, with one half highly finished and the other half largely blank, is typical of Renaissance design drawings. Such drawings were considered works of art in their own right and were sought after by early collectors.’

Francesco di Simone Ferrucci (1437-93) or Andrea di Piero Ferrucci (1465-1526), design for an altar with three niches, late 15th century, pen-&-ink, watercolour, 38 x 18.5 cm., V & A

‘Design for an altar with three niches in the retable containing sculpture, and a ciborium above. Inscribed on the mount in an old hand (probably 17th century) ‘Cosimo Roselli 1416-84’; pen and ink and wash, the niches and part of the altar-table tinted with red watercolour; the top of the sheet cut in an arch.’

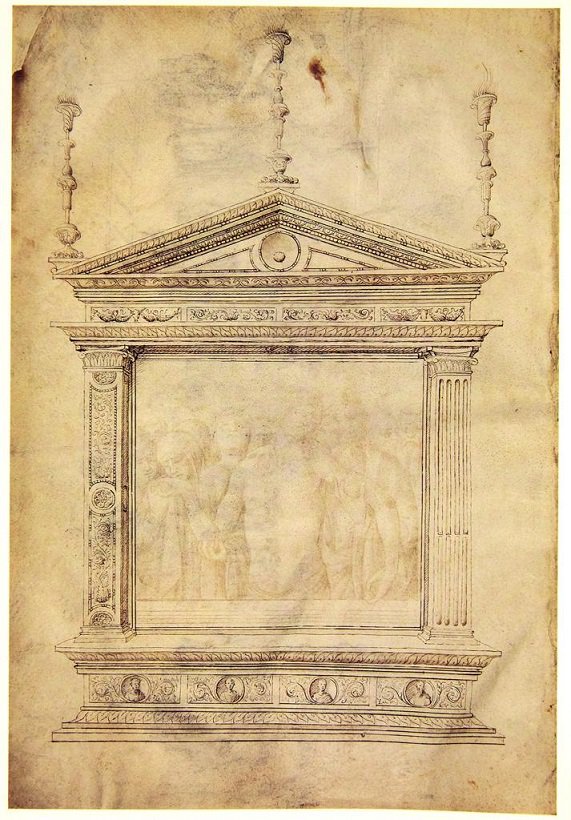

Alvise Vivarini (c.1445-1505), Madonna & Child with saints and angels, c.1490-1500, stylus lines, pen-&-ink, wash and white, 34.7 x 24.9 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 990069

F. Ames-Lewis & J. Wright, Drawing in the Italian Renaissance workshop, V & A, 1983, p. 276

‘The drawing most probably contains the design for the outer frame in which the altarpiece would have been set. Intended to blur the break between actual and fictive architecture further, it is difficult to tell where the design for frame ends and the design for painting begins’.

Filippino Lippi (c.1457-1504), a lion & part of an oval frame, metal point and white heightening, 18.6 x 13.5 cm., Galerie degli Uffizi

Vittore Carpaccio (1460/65-1525/26), design for an altarpiece, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, 48.5 x 32.3 cm., KKS6269, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Vittore Carpaccio (workshop; 1460/65-1525/26), design for an altarpiece with the Coronation of the Virgin, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, 48 x 31.3 cm., KKSgb8412, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

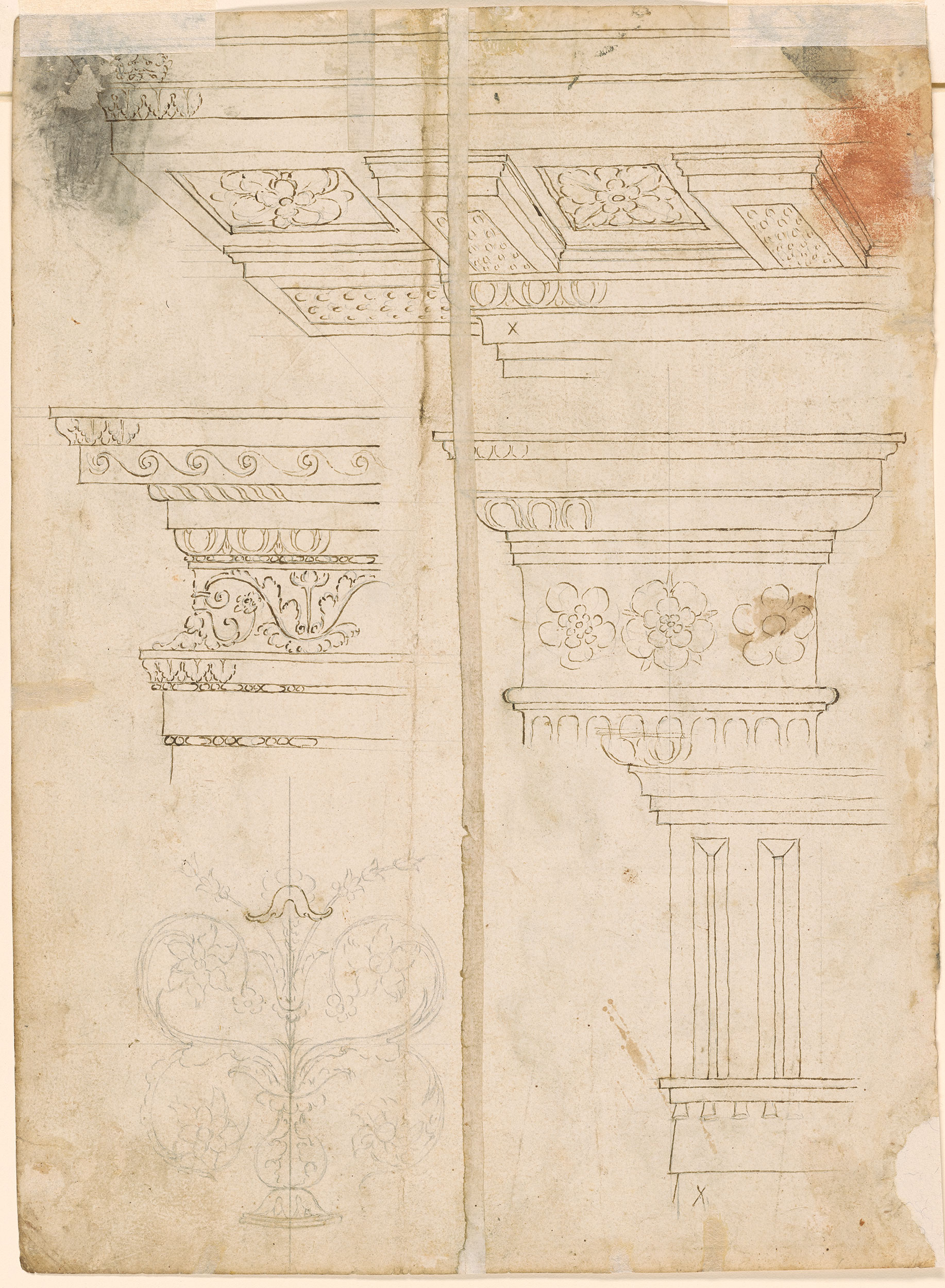

Anon., 15th century Italian school, recto: grotesque designs for a pilaster ornament; verso: underview of a cornice & studies of pilasters, pen-&-ink, black chalk, 28.1 x 20.7 cm., The Morgan Library & Museum