Italy

16th century Italian drawings

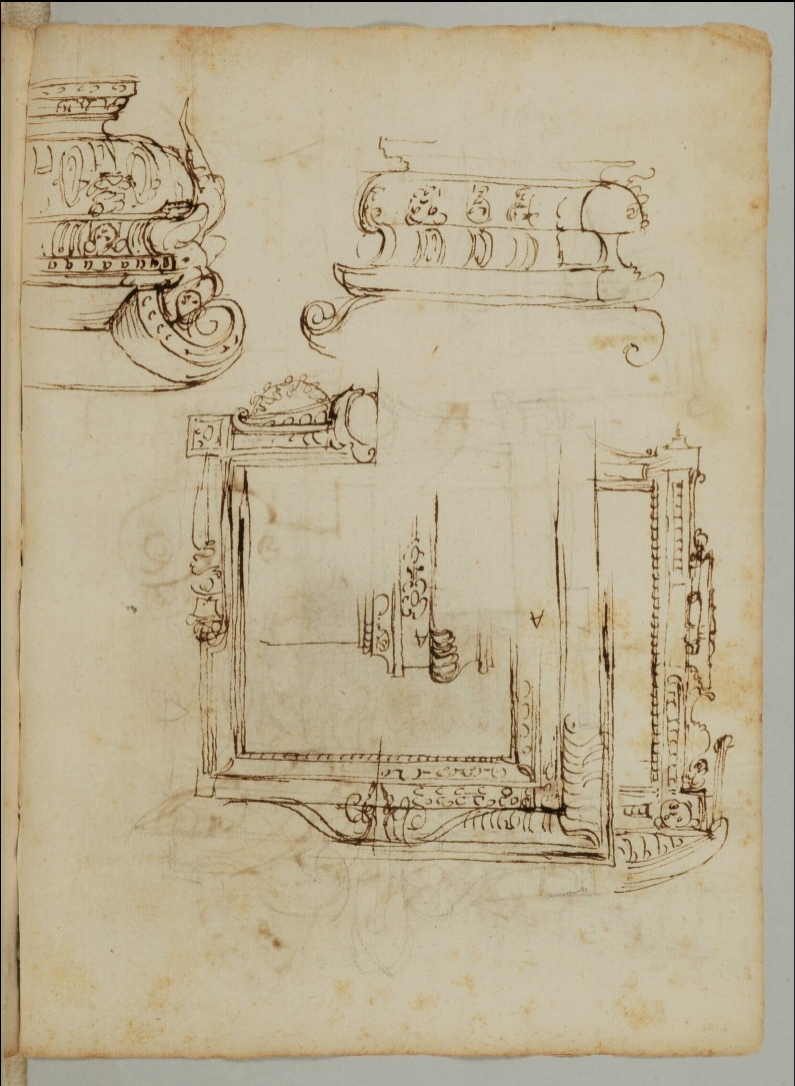

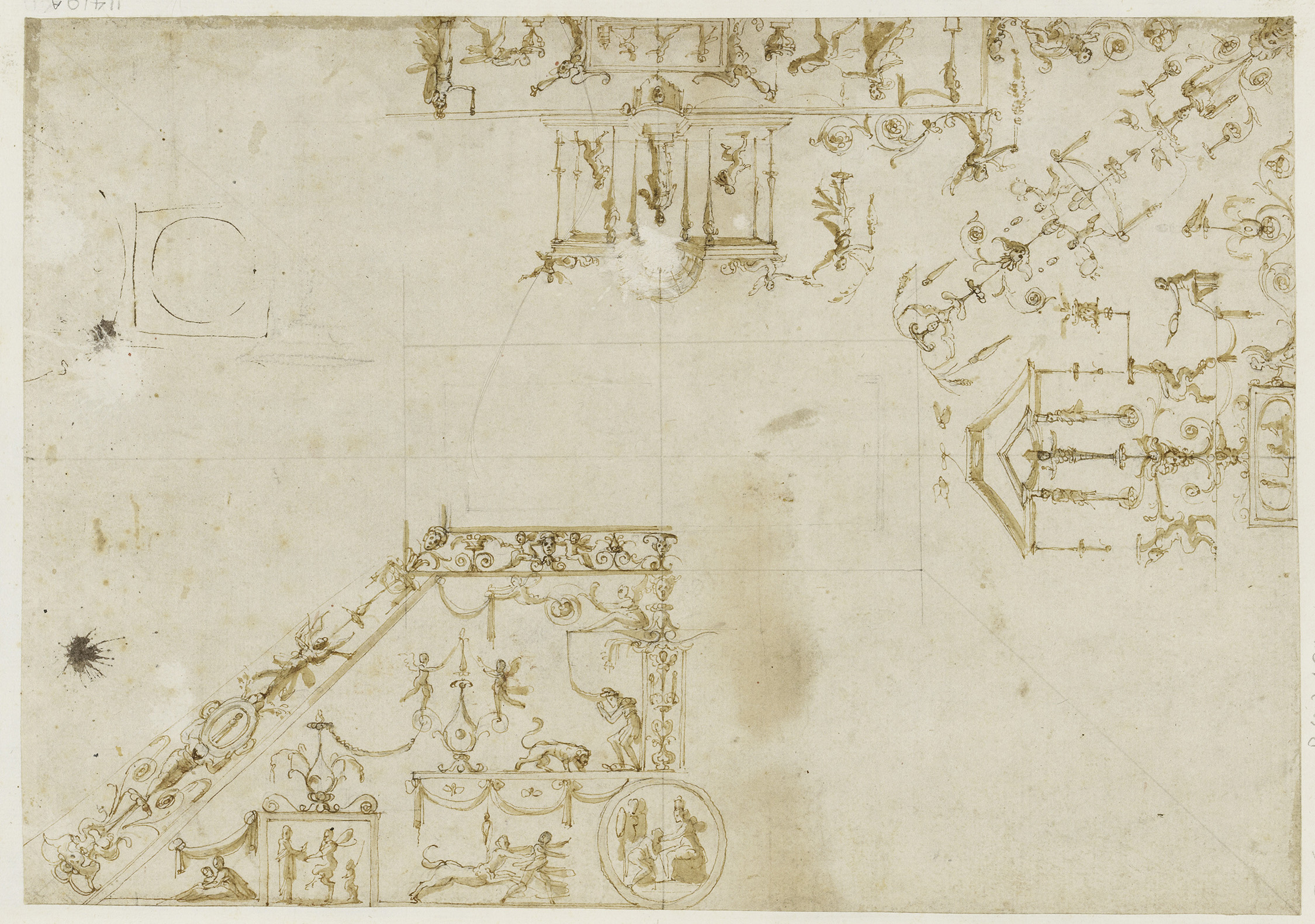

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), capitals and grotesques (verso of page), 1501-05, pen-&-ink, pencil, 18.5 x 18.1 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

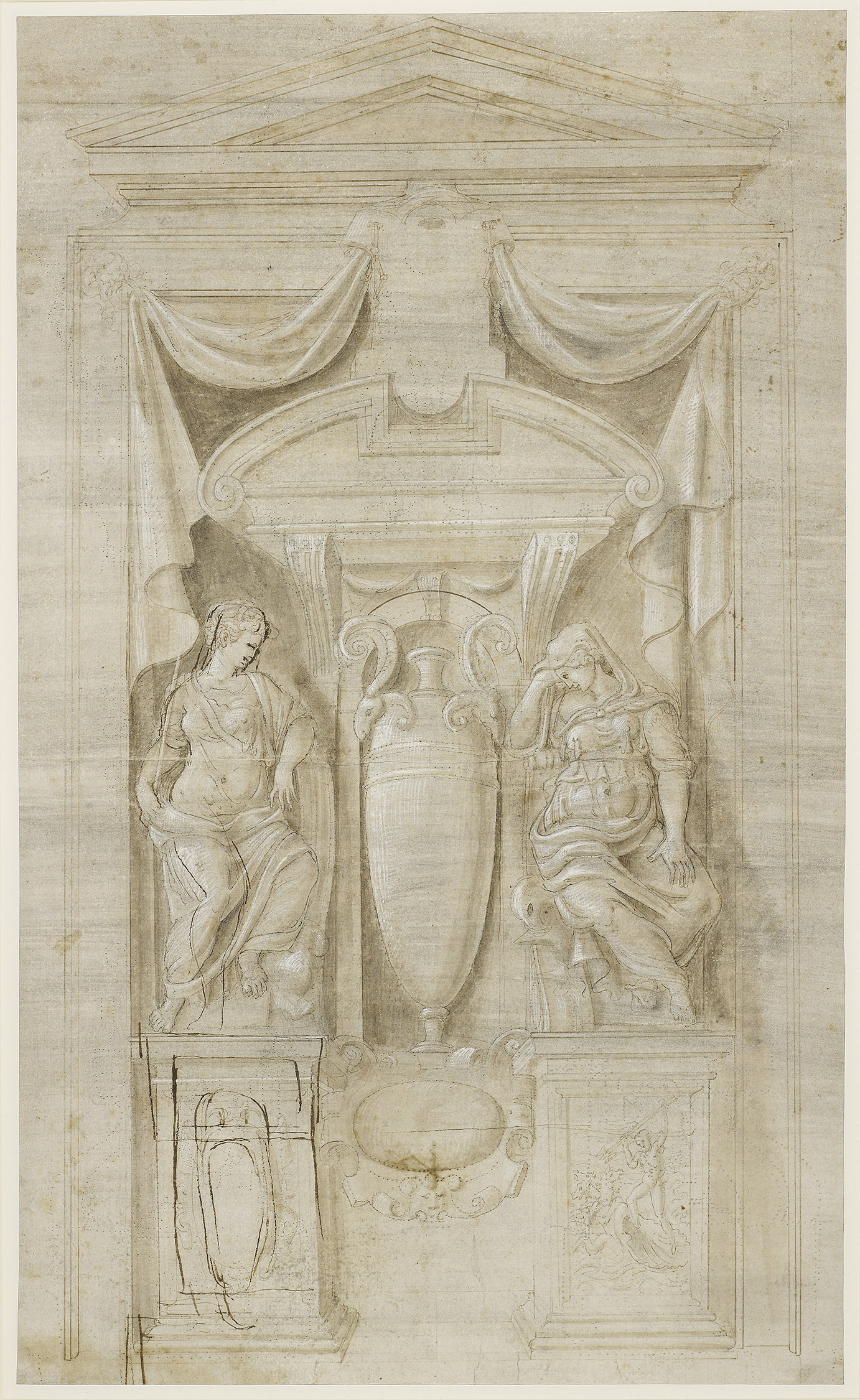

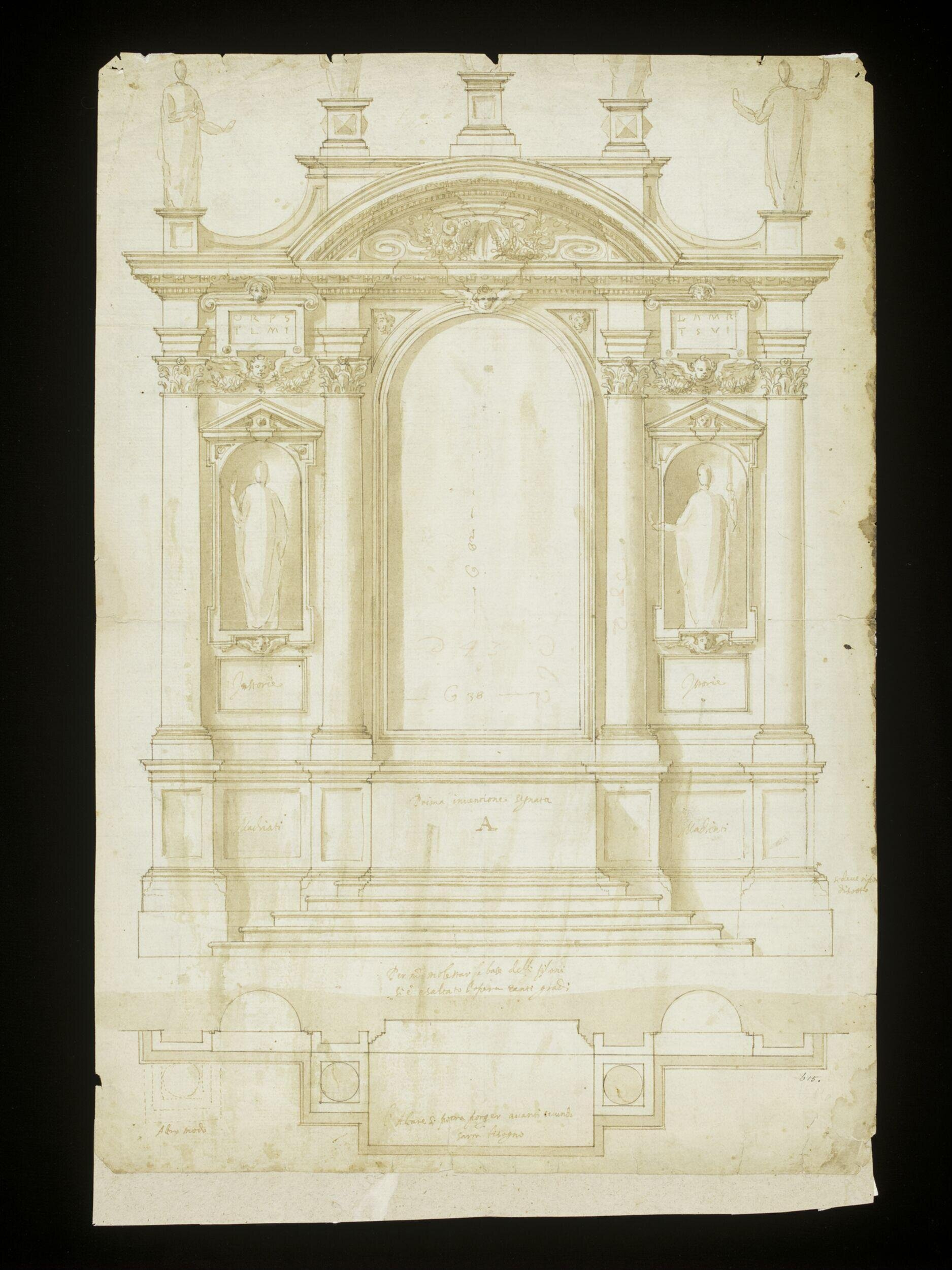

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), Tomb of Pope Julius II della Rovere, 1505-06, pen-&-ink, wash, pencil, 51 x 31.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘By 1505, eight years before his death, Pope Julius II della Rovere (reigned 1503-13) had apparently already began contemplating plans to erect a grandiose tomb for himself in the new St Peter’s Basilica being constructed according to Bramante’s design, and entrusted Michelangelo with the sculptural project. In March-April 1505, Michelangelo probably began the first drawings for the tomb project which according to a first (lost) contract, was to cost 10,000 ducats, was to be finished in five years, and was to be sited in St Peter’s…

… the tomb of Julius II was to have been a three-story freestanding monument and may have included as many as forty-seven large figures carved of Carrara marble, but Michelangelo’s project was interrupted by other papal commissions, chiefly the frescoes on the Sistine Ceiling (1508-1512), with which the early drawings for the Julius Tomb share considerable similarities of style. Following the pope’s death on 21 February 1513, Michelangelo signed a second contract for a reduced version of the tomb to be finished in seven years. For a number of reasons, the Metropolitan Museum’s drawing with its subtly pictorial illusionism of the architecture appears to reflect the first version of the Julius Tomb project, around 1505-6…

…the ensemble portrayed in the Metropolitan Museum drawing would have rested on a stepped base, as is seen in the Uffizi and Berlin designs, but which in this case is cropped by the lower border of the sheet.’

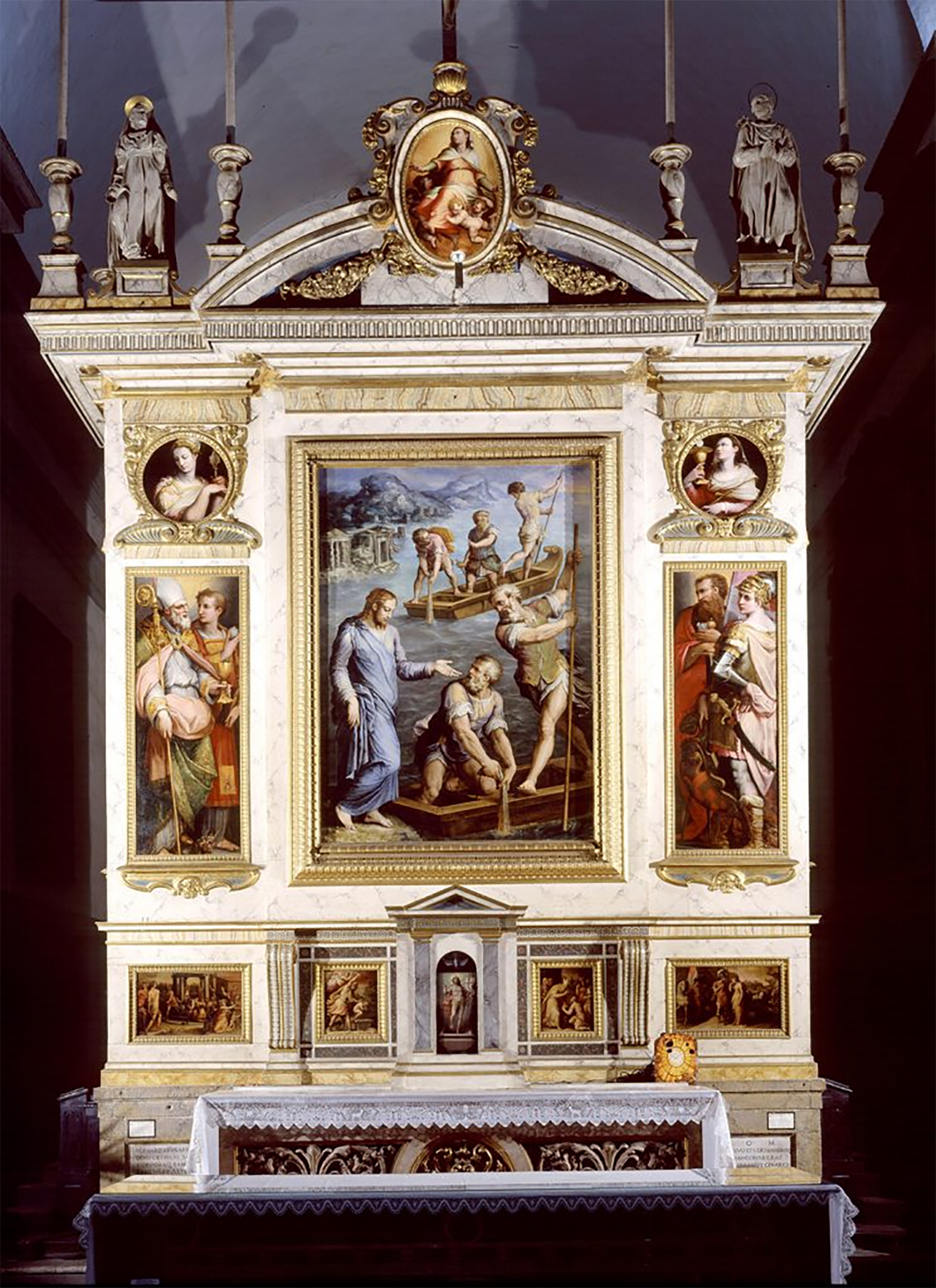

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), Tomb of Pope Julius II della Rovere as executed, 1545, San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. Photo: Web Gallery of Art

‘… Michelangelo’s forty-year ordeal in producing the Tomb of Julius II did not end until 1545, when the present, much scaled-down structure was installed in San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome…

Carmen C. Bambach (2009, revised in 2014)’

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), letter from Florence to Cardinal Bernardo Dovizi da Bibbiena in Rome, architectural drawing in red chalk (draught), June 1520, Casa Buonarroti, Florence (66A)

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), capitals & profiles of bases, c.1515-18, pen-&-ink over stylus, 27.4 x 21.4 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), recto: drawing of Doric capital & entablature from the Theatre of Marcellus; verso: ten Doric capitals; 1515-18, red chalk, 28.8 x 21.6 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), recto: architraves, entablatures, columns; verso: architectural details, including column of Temple of Castor; 1515-18, red chalk, 27.9 x 20.8 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), Ionic capital cornice & base, c.1515-18, red chalk, trimmed, 13.3 x 21.2 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), study for one of the Medici tombs, Sagrestia Nuova, 1520-21, black chalk, 29.4 x 20.9 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

Michelangelo, tomb of Lorenzo de’Medici, Sagrestia Nuova, Florence

This and the following designs are included here because of Michelangelo’s radical influence upon Mannerist architecture and also, therefore, on Mannerist picture frames.

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), demonstration drawing for a door in the Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence, Casa Buonarroti, Florence

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), study for a door with the papal arms for the Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence, 1526, pen-&-ink, red chalk, pencil, stylus lines, 28.2 x 20.8 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

‘The two architectural studies in pen and ink on either side of this sheet are studies for the door between the vestibule and reading room of the Biblioteca Laurenziana in the cloister of the Medicean church of San Lorenzo in Florence. That on the recto is a study for the reading room side of the door; that on the verso for the vestibule side, Michelangelo having traced its dimensions from the study on the recto: the two portal studies thus possess the same relation on paper as the portals for which they were destined. The Laurenziana was commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, who became Pope Clement VII in November 1523. The studies can be precisely dated to April 1526 thanks to a letter from Giovan Francesco Fattucci ( a canon of Florence cathedral who was his main contact at the papal court) thanking him for sending a ‘drawing of a door’. The door was not executed until after August 1533, however, the papal arms being omitted – Clement died in 1534….’ [continued]

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), design for the Porta Pia, 1561, Casa Buonarroti, Florence, 102 A

‘The architectural project of Porta Pia was one of Michelangelo’s last labours. Between the end of 1560 and the beginning of the following year, Pope Pius IV Medici di Marignano (1559-65) decided to build a new road, to which he would give his name, connecting the Quirinal Hill to the Aurelian Walls, between the Porta Salaria and the Porta Sant’Agnese…. On 18 January 1561, a letter from the Duke of Mantua’s ambassador to the Papal Curia, addressed to Gonzaga, informed that work on the construction of the street was already under way, at the end of which a gate, also named after the Medici pope, was to be opened. In May the masons began to break down the walls, and on 18 June the foundation ceremony for the gate and the placing of the foundation stone took place. On 2 July the contracts for the building were stipulated… That Michelangelo was the artist responsible for the design of the gate is also documented by the payments collected on his behalf by the agent Pier Luigi Gaeta, and by the testimony of Giorgio Vasari, who in his Life of Michelangelo (1568) recalls how «being requested at this time by the Pope for a design for the Porta Pia, Michelagnolo made three, all fantastic and most beautiful, of which the Pope chose the least costly for putting into execution» (VASARI (1568) ed. Ekserdjian, de Vere 1996, II, p. 729).’

Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), design for the Porta Pia, 1561, Casa Buonarroti, Florence

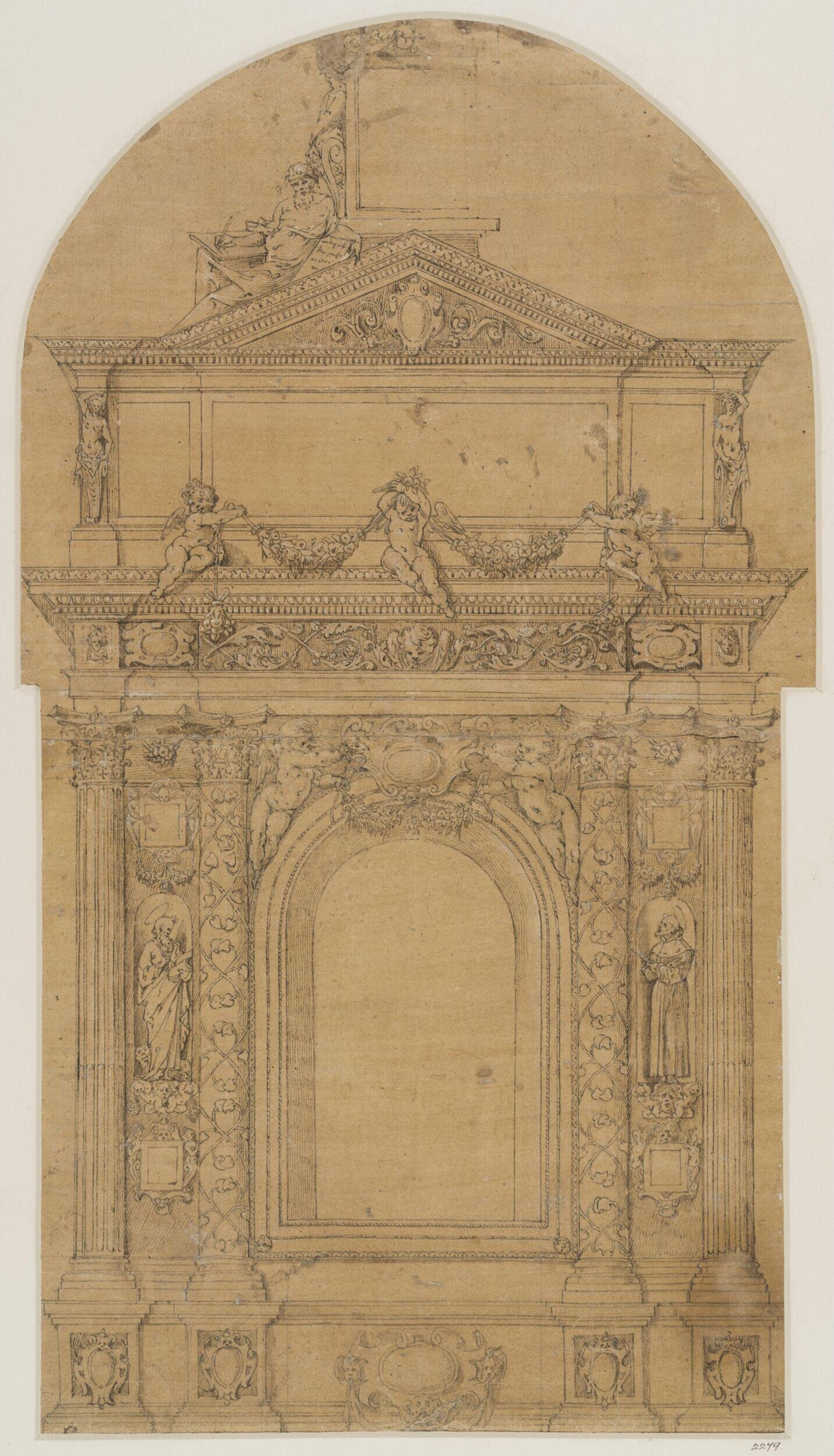

Andrea Sansovino (c.1467-1529; attrib.), design for sculpted altarpiece, c.1505-10, pen-&-ink & wash, 44.9 x 28.8 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 990208

‘A design for a marble altar incorporating several sculptures. To either side of the altar table is a blank escutcheon surmounted by a cardinal’s hat within a circle. In a niche at the centre are the Virgin and Child enthroned, with two angels holding a crown above her head, and a donor kneeling on the right. In smaller niches to right and left are Sts Barbara and Catherine of Alexandria; above each of these are two apostles in still smaller niches. The whole is surmounted by another structure with a double niche with the angel of the Annunciation and the Virgin Mary; to left and right of this structure are personifications of Faith and Hope.

The drawing is constructed with much pinpointing and ruled stylus underdrawing. The style and general arrangement of the architecture, and the style of the figures, are close to Andrea Sansovino’s tombs of Cardinals Ascanio Maria Sforza and Girolamo Basso della Rovere, in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome (c.1505-7). Sansovino’s own drawing style is obscure, but it is hard to know who else could have been responsible for such an ambitious design in this manner. This would have been one of the most impressive assemblages of sculpture and architecture of High Renaissance Rome had it been executed, and it is most unfortunate that the patron cannot be identified (as his shield is left blank)’.

Girolamo da Santacroce (c.1480/85-1556), design for an altarpiece, red chalk, ink, wash, 33.3 x 22.5 cm., Rijksmuseum

Agostino Busti (Il Bambaia; 1483-1548), design for an altarpiece, c.1515, metalpoint, ink, white heightening, 29.7 x 33.1 cm., Gabinetto dei Disegni, Castello Sforzesco

‘…the structure depicted is conceived as a triumphal arch: the central section… houses two kneeling saints and a central arch, flanked by figures of the Annunciation; the two lateral niches house SS Louis of Toulouse and Anthony of Padua. A frieze with five episodes from the life of the Virgin decorates the upper part of the structure, surmounted by the figures of the Redeemer, two angels, and the evangelists John and Matthew. The drawing has been associated with the creation of an altar for the church of Santa Maria del Giardino in Milan. In 1515 Bambaia actually participated in the competition announced for the execution of this work, in collaboration with Geronimo Della Porta and Cristoforo Lombardi, but the altar was then created for a more modest price by other artists between 1519 and 1523.

The drawing has recently been attributed to the miniaturist and goldsmith Giovanni Giacomo Decio.’

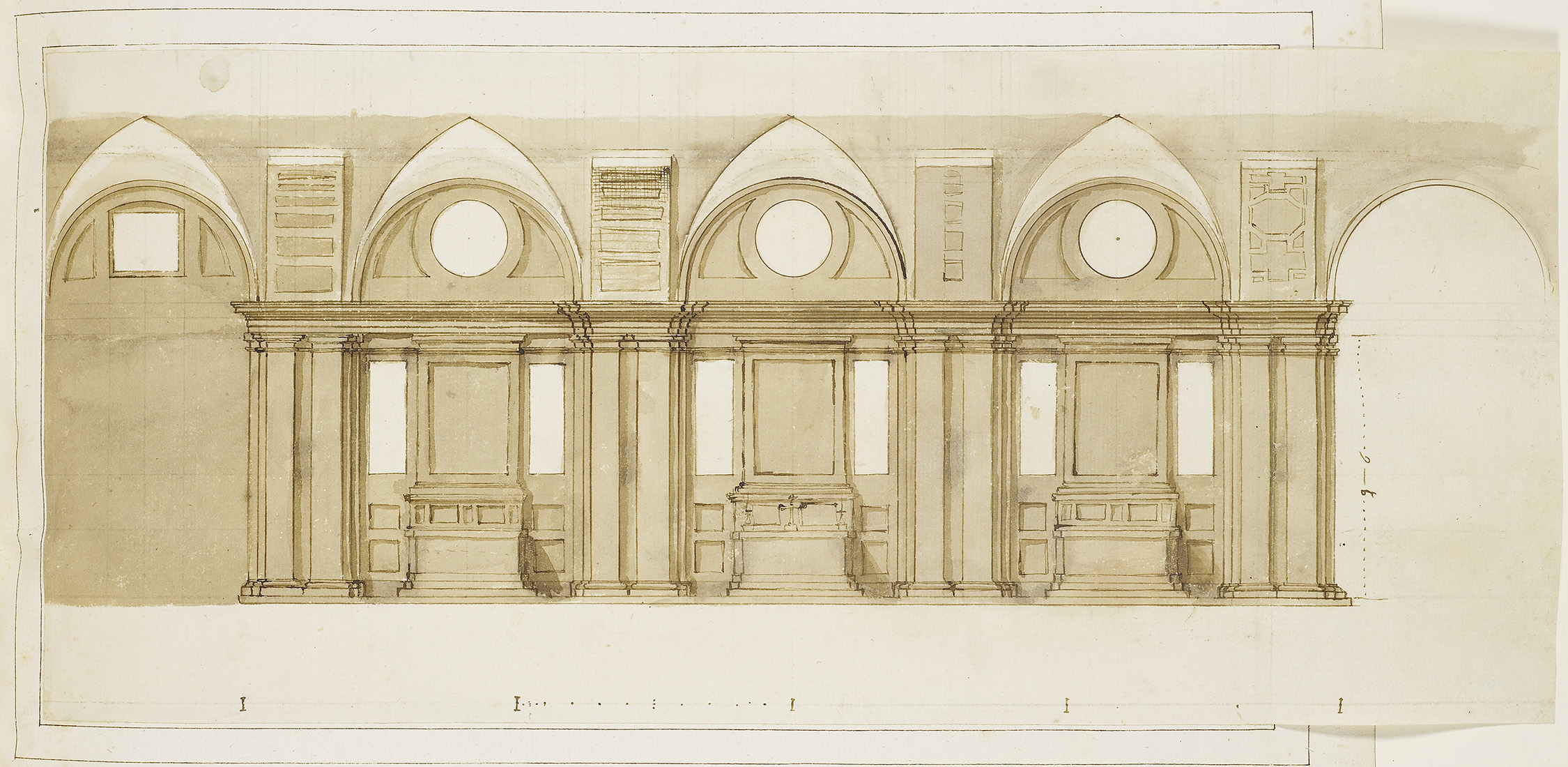

Giuliano da Sangallo (c.1445-1516; previously attributed to Francesco da Sangallo), design for a tabernacle, 1515-16, black chalk, pen-&-ink, wash, 38.8 x 19.4 cm., Gabinetto dei Disegni, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 1669 A

‘…The graphic characteristics of this atypical demonstration drawing… suggest an… identity [different from Francesco] for its author. While Francesco’s projects are resolved in a more restrained, almost didactic style, and are rigorously drawn in orthogonal projection, the casual manner and free stroke of inv. 1669 A – where the pen confidently follows the few construction lines drawn in black chalk, with generous shading to mark details in semi-perspective – are more recurrent in the corpus of Giuliano da Sangallo, Francesco’s father, to whom this tabernacle project can more accurately be attributed. The inscription of the frieze with the ancient capitals, for example, is comparable to the many epigraphic reconstructions in his antiquarian notebook, the Barberini Codex 4424 of the Vatican Apostolic Library, even in the ‘NECELSIS’ and in the Tuscanism of the ‘GROLIA’; but the most compelling comparison is with inv. 281 A, the last of the series of projects for the facade of San Lorenzo, and also the one with the most certain attribution and identification. Both sheets repeat similar architectural details – the sequence of mouldings in the pediment, the Doric order with collar and rosettes of the Basilica Emilia type – while certain abbreviations in the design are even superimposable, such as the synthetic way of describing the grooves, which fade a few millimeters from the ends. On the pediment of the tabernacle, then, are three lit candelabras with flickering flames, just like the spherical vases along the entire balustraded terrace of the façade of San Lorenzo. Sheet inv. 281 A, on which the dedicatory inscription to Leo X with the year “MDXVI” can be read, was likely completed during the pontiff’s stay in Florence, that is, between November 30, 1515 and February 19, 1515…’

Francesco Granacci (1469-1543), Madonna & Child with saints, 1520s, pen-&-ink, wash, heightened with white, 30.1 x 26.4 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

‘This is probably the finest and most important of Granacci’s surviving drawings and typifies his delicate, slightly archaic style. Although clearly conceived as the design for an altarpiece – the artist has been at pains even to draw the frame and to pick out the small predella scene of the ‘Pietà’, bottom centre – no corresponding picture has so far been traced. From its resemblance to the composition of Granacci’s altarpiece in S. Giovanni Battista at Montemurlo, the drawing may be dated in the early 1520s’.

Baldassarre Peruzzi (1481-1536), design for organ case, c.1520, pen-&-ink and white highlights, 56.5 x 38 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 905495

‘A large design for a secular organ case. At upper centre is the god of music Apollo, accompanied by the Muses, inspirational goddesses of the arts. In the pediments are the emblems of Federico Gonzaga, marquis (and later duke) of Mantua. Peruzzi’s design was probably drawn in Rome and sent to Mantua for local carpenters and woodcarvers to construct. At the centre, where the organ pipes would be, Peruzzi notes possible adjustments to the design:

‘FIDES / B / E da notare che inquesta faccia vaño le cañe piccole delo organo / & da laltra dove vaño le cañe grandi va levato via el collari/no segnato .B. preterea sepo volendo tor via el fastigio overo / quarto tondo socto ali satyri e qui dare la cornice dricta ussando / el fastigio sup[er]iore. Vlterius se po levare luno e laltro fastigio / e farlo a modo de arco triumphale’

[‘It is to be noted that the small pipes of the organ are on this side and that, on the other, where the large pipes are, the frieze marked B is left out. Besides, if it is desired, the pediment or quarter-circle underneath the satyrs can be removed and the cornice here left straight, using the upper pediment. Further, both pediments can be removed and it can be made in the form of a triumphal arch.’]

In the upper pediment is the shield of the Gonzaga of Mantua, and in the rounded pediment below is an emblematic device (impresa) depicting Mount Olympus with a road spiralling up its side, topped by an altar (here with a burning offering), and the word fides (faith). This device was used by Federico II Gonzaga after he succeeded his father as Marchese in 1519. The tradition that the Emperor Charles V conferred the device on Federico for his valour during the defence of Pavia against the French in 1522 seems to have no foundation, but when the Emperor created Federico Duke of Mantua in 1530 he allowed him to add the device to the Gonzaga arms….

… There is no scale on the drawing, though the density of decoration suggests that it was to be large. The architecture relates closely to a design by Peruzzi for an altar surround in the Getty, the measurements on which give a total height of around 3m (10ft), and it may be supposed that the organ was to be about the same size’.

Baldassare Peruzzi (1481-1536), design for an altar, c.1527, black chalk, pen-&-ink, wash, stylus underdrawing, 45.4 x 37.8 cm., inscr. centre right: ‘Quando q / pare sta / postreng / columnj / emjejchlj / tanto ch / vero e / ne dj / for / le jndi / la cornjce / vada dr / schizo s’, plus various measurements at right, centre, and bottom, J. Paul Getty Museum

‘Numerous details indicate that Baldassare Peruzzi made this design for an altar as a presentation drawing, to be shown to a patron for approval. He took great care when drawing the intricate decoration of the altar, meticulously outlining the scrolling rinceaux interlaced with animals along the frieze and base of the columns and carefully shading the delicate fluting, dentils, and egg-&-dart motifs. He also showed the effects of shadows on the top and right parts of the frame and noted the size of various components on the design so that this large altar could be built with precision.

Although this drawing does not relate to any known structure, it probably represents an unexecuted design for a side altar for the cathedral of Siena. Three of the saints in the niches appear facing to the right, toward the main altar, indicating that this altar would have stood in the left aisle’.

Baldassare Peruzzi (1481-1536), design for the decoration of an altarpiece, 29 x 40.2 cm., brush and ink, stylus, wash, pricked for transfer, Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

Inscribed on the back:

‘Drawing representing a woodwork tabernacle for an altar decorated with architecture, with, in the middle, the Eternal Father and the Holy Virgin; on the side in niches several Saints ; Drawing in pen washed with Chinese ink’.

Franciabigio (c.1482-1525), design for an altarpiece for Santo Spirito, Florence, c.1513-15, Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

This is a design for the Altarpiece of St Nicolas of Tolentino, where the figures of the saint and the two lateral angels were carved wooden sculptures; the chapel is now occupied by a figure of the saint flanked by two panels of angels painted by Franciabigio, whilst the (seven?) sections of the predella have been dispersed to various museums.

The statue of San Nicola da Tolentino currently in place in Santo Spirito

The Catalogo generale dei Beni Culturali explains the original and present configuration of statues/ paintings under the entry for one of Franciabigio’s painted angels:

‘The wooden statue of St Nicholas and the two angels housed in the marble frame of the chapel were supposed to be part of a complex wooden architectural altar – thought to have been lost until now, following the 17th century renovations of the chapel itself. The complex was composed of the two… angels, two tondi depicting The Annunciation and a series of predella panels with episodes from the life of St Nicolas, the sequence of which has been reconstructed by Laskin and Parronchi.

The altarpiece is depicted in a drawing currently in the Louvre (above), which belonged to Vasari. According to Vasari, Jacopo Sansovino made the design for the wooden statue of St Nicholas, carved by Nanni Unghero and placed in the centre of the altar, and executed the terracotta models for the two angels which were to flank St Nicholas. According to M. Killay, the two models, of which no trace remains, could have been a source of inspiration for the two paintings by Franciabigio with the same subject.

In a room in the convent of Santo Spirito, [Alessandro] Parronchi recently found the altar of St Nicolas, complete with a Sansovino architectural frame and paintings by Franciabigio. The only exception was the predella, which has been scattered to various museums. The central niche, the arch of which has a medium-sized opening (today occupied by a panel of no artistic value and an 18th century crucifix) raises the question of whether the statue of the saint still on the altar of the church is truly the one that Vasari believes was designed by Sansovino and carved by Nanni Unghero. The fact that the altar recently discovered also features the two carved wooden lateral angels seems automatically to exclude those currently in the chapel from being part of the original altarpiece; but for the moment it is not possible to provide a solution to this problem. Parronchi also observes that the surviving panels of the predella, while not showing any correspondence in terms of measurements with the two painted angels in the church, are well suited to the dimensions of the panels in the rediscovered altarpiece in the convent’.

Design for an Altarpiece, catalogued as attributed to Benedetto Diana, Assumption of the Virgin, © Trustees of the British Museum; credited by Dr. Kiril Penušliski to Girolamo da Santacroce (1480/85-c.1556)

Girolamo da Santacroce (1480/1485-1556), study for a processional standard, SS Christopher, Roch and Sebastian, first half 16th century, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, 32.9 x 22.8 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

‘A contract drawing for a processional banner, probably for a Venetian church or confraternity (Scuola), comparable in format with one by Vassilacchi in the BM 1895,0915.761. For a list of other drawings of this type see the latter’s curatorial comment. The attribution to Santacroce, which dates from the end of the 19th century (it was sold as such in Habich’s sale in 1899), is an entirely plausible one, although it must be said that he is a fairly unknown quantity as a draughtsman and the drawings assembled under his name are certainly not all by the same hand (see Tietzes pp. 245-6). The only more or less certain study by his hand is the St John Chrysostom and Onofrius at Christ Church, Oxford (J. Byam Shaw, ‘Drawings by Old Masters at Christ Church Oxford’, Oxford, 1976, I, no. 712, II, pl. 405) which is a study for two panels, originally organ shutters, in the church of S. Giovanni Crisostomo, Venice (D. Della Chiesa and E. Baccheschi, ‘I pittori da Santa Croce’, in ‘I Pittori Bergamaschi, il Cinquecento’, II, Bergamo, 1976, no. 50, p. 34, illustrated p. 56). The shutters were once given to Mansuetti, Fiocco’s suggestion that they are the work of Girolamo in collaboration with his son Francesco was accepted by Venturi, Berenson, Heinemann and more recently by Chiesa and Baccheschi.

Other drawings attributed to Girolamo include the ex-Earl of Harewood contract drawing for a polyptych (Tietzes no. A 1402; Frerichs 1966, figs 1 and 2), signed by the notary Bartommeo da Raspis in June 1526, now in the Rijksprentenkabinet, Amsterdam; and a squared study at Darmstadt (AE 1264; Gernsheim 19197; Tietzes A 1400) for the painting of the Last Supper in S. Martino, Venice (Della Chiesa and Baccheschi p. 35, no. 55, illustrated p. 65). The Tietzes rightly observed that the Darmstadt drawing is much freer than the finished painting, and it may well be a younger member of the Santa Croce workshop. Girolamo’s son Francesco is the most likely candidate as the Darmstadt study is stylistically not unlike an altarpiece design traditionally ascribed to him in the Padre Resta album in the Ambrosiana, Milan. Even this attribution is not straightforward as Frerichs follows Morelli in claiming it for Girolamo.’

Bartolomeo Ramenghi (c.1484-c.1542), design for an altarpiece, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, 37 x 24 cm., Gallerie degli Uffizi

Carla Bernardini established ‘the relationship between this drawing and an altarpiece depicting the Madonna & Child in Glory with saints painted for the Church of Santa Maria della Misericordia in Bologna…

…The diverse activities of Ramenghi’s workshop, which was dedicated not only to producing paintings, but also to the decorative and applied arts, such as the creation of cartoons for intarsia and the repainting of ancient statues, has been emphasized for a long time…. The sources also report the relationships that Bagnacavallo had with the woodworkers, for whom he designed frames even for altarpieces that he had not painted (Mazza 1983). This could not have been an isolated example, since in several drawings from the region of Bologna there are related designs for frames, such as a drawing in Oxford, the attribution of which oscillates between Bagnacavallo and Innocenzo Francucci da Imola, a design for an altarpiece by Innocenzo in the Albertina, Vienna [see below], and Biagio Pupini’s Madonna & Child appearing to SS Jerome, Paul & Catherine, 1537, in the Louvre’ – see below.

Bartolomeo Spani (1468-1539), design for a tabernacle, c.1500-20, pen -&-ink, wash, stylus indentations, 25.5 x 16.5 cm., The Morgan Library & Museum

‘Marcello Calogero has recognized that this is one of four drawings at the Morgan (including I, 8; I, 9; I, 43; and I, 81) — all previously anonymous — that can be attributed to the goldsmith and sculptor Bartolomeo Spani. The four sheets, and two others whose present whereabouts are unknown, were framed together when in the collection of Stefano Bardini in Florence. See Fahy, Everett, Dipinti, disegni, miniature, stampe / di Everett Fahy (Firenze: A. Bruschi, 2000), 60.’

Andrea di Cosimo (attrib., 1477-1548), design for a family portrait frame with a crest, possibly of the Lenzi family?, 1490s-1540s, black chalk, 20.5 x 29.1 cm., Rijksmuseum

Andrea di Cosimo (attrib.; 1477-1548), design for a frame, 1490s-1540s, black chalk, 20.5 x 29.1 cm., Rijksmuseum

Domenico Beccafumi (c.1486-1551), design for a chapel with The Annunciation, Sacré conversazione and St Sebastian, c.1517, pen-&-ink, black chalk, stylus, compass marks, 29.8 x 21.4 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘Decorative scheme for a chapel or oratory (A. De Marchi), … The exedra here extends the architecture of the foreground so that it is not easy to decide whether this Sacré conversazione should have been painted on the wall of a half-domed apse (A. De Marchi, cit.) or on a painting whose base would correspond to the level of the altar table… The triptych arrangement of the lateral figure [St Sebastian] and the other, not drawn, which should have been its counterpart, with a central subject developed in a higher and arched space, may seem traditional if we think of the polyptychs of Vecchietta… but it appears profoundly modern if the drawing is read as spatial architecture, articulated in a Serlian mode, where the figures transgress the limits of their frames…’

Correggio (1489-1534), drawing for Madonna di San Giorgio, before 1530, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, 23.8 x 18.8 cm., Kupferstich-Kabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden

A study ‘… for the Pala di San Giorgio, an altarpiece executed around 1530 for the lay brotherhood Petrus Martyr in Modena.’

Correggio (1489-1534), Madonna di S Giorgio, 1530-32, o/c, 285 x 190 cm., now in a Dresden gallery frame, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Biagio Pupini (c.1490-c.1575), Madonna & Child appearing to SS Jerome, Paul & Catherine, 1537, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, 37.5 x 24.5 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘A similar style of frame is found on other drawings in the Gallerie degli Uffizi, Inv. 1755 O et Inv. 1430 F’.

See Bartolomeo Ramenghi, design for an altarpiece, above.

Innocenzo Francucci (1490/94-1547/50), design for an altarpiece with the Madonna & Child, angels, and God the Father, pen-&-ink, wash, 37.9 x 24.1 cm., Albertina, Vienna

‘Design for an altarpiece; its attribution based on its relationship to a drawing in the Uffizi, no. 14583F’.

Giulio Romano (1492/99-1546), design for the tomb of Sigismondo Gonzaga, c.1537, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, black chalk, 25.0 x 40.5 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘Design for the funerary monument of the Bishop-Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga (died 1525), commissioned by his nephew, Cardinal Ercole, for the Duomo, Mantua. The monument was under construction in 1537 (‘Giulio Romano. Repertorio di fonti documentarie’, by Daniela Ferrari, with an introduction by Amedeo Beluzzi, 2 vols., Mantua, 1992, II, p. 732-733), but the projecting section was destroyed between 1683-85 and replaced by a Baroque altar (G. Rebecchini, ‘Sculture e scultori nella Mantova di Giulio Romano, 1: Bernardino Germani and the tomb of Pietro Strozzi’, in Prospect, October 2002 (2004), p.108.

Remains of the fresco’d angels from Giulio Romano’s design for the tomb of Sigismondo Gonzaga in the Sacristy of the Duomo, Mantua

The fragments of the fresco decoration of the tomb, executed by Fermo Ghisoni, although half-hidden by this altar, leave no doubt as to the destination of the drawing [above]: we find the same angels holding torches, drawn on either side of the sarcophagus, in front of curtains swagged on the wall. Giulio Romano’s final design was not fully executed, since Sigismondo’s remains were placed in a wooden box, lined with velvet, and supported by two golden lions; presumably, therefore, neither the perspectival space containing the monument nor the weeping figures seated on either side of the sarcophagus were realized (R. Berzaghi, in cat. exp. Giulio Romano, Mantua, Museo Civico Palazzo Te, Palazzo Ducale, 1989, texts by EH Gombrich, M. Tafuri, S. Ferino Pagden et al., p. 567). The squaring up of the sheet, limited to the upper part of the drawing, at the level of the angels, seems to confirm this hypothesis’.

Polidoro da Caravaggio (1495 -1543), projet pour un monument à double registre, c.1528, 31 x 18.5 cm., pen-&-ink, wash, Artcurial, 26 March 2025, Lot 73

‘This is probably a presentation drawing to be submitted to the commissioner, for a tiered wall tomb. The upper part features a sarcophagus surmounted by the personification of Fame, and at the lower level two winged putti support funerary urns. Below, on the left, is the coat of arms of the city of Messina (a field covered with a cross), accompanied, on the right, by an unknown coat of arms, probably those of the commissioner. Pierluigi Leone de Castris has supported the hypothesis of a possible commission by Giovanni Marullo (fl. 1518-d.57), Count of Condojanni, who twice, in 1528 and 1535, held the office of strategos (the local judicial officer) of Messina. Marullo was the commissioner of Polidoro’s most successful work in Messina, the monumental polyptych in the Church of the Carmine, unfortunately destroyed by an earthquake in 1724, but to which numerous drawings attest. The Romanesque style of the present sheet suggests an earlier date than Polidoro’s drawings for the Resurrection (the main panel of the Carmine polyptych). This draiwng could have been executed around 1528, when Polidoro had just arrived in Messina from Naples and Giovanni Marullo had just been appointed strategos.’

Perino del Vaga (1501-47), project for a wall decoration, c.1522, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, 40.9 x 26.8 cm., J. Paul Getty Museum

‘Perino del Vaga produced this delicate ink and wash design as a study for frescoes in a chapel within the Vatican. The Adoration of the Magi appears on both sides of the arched, recessed window at the top. The three kings gather to admire the Christ Child standing in his mother’s lap on the right. In the centre of the lower register is the Crucifixion scene, surrounded by scenes from the Passion of Christ, the theme of the chapel. The coats of arms of various popes fill the window frame at the top.

In 1520 this chapel was assigned to the Vatican’s Swiss Guards, and shortly afterwards Perino was commissioned to decorate it. It is believed that this drawing was made around 1522 because it contains the coat of arms of Pope Adrian VI, who only led the Church for a year, from 1522 and 1523. Perino began work on the frescoes in 1522 but he never completed them because of a serious plague outbreak in 1523. The frescoes were later finished by Polidoro da Caravaggio’.

Perino del Vaga (1501-47), drawing of Jupiter and Juno for the Furti di Giove tapestries, c.1532-35, pen-&-ink, was, white heightening, 43.2 x 40 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘One of Perino’s most beautiful and important drawings, this monumental depiction of the Roman gods holding hands as they recline on their marriage bed is a highly-finished study for one of the woven panels in a lavish and costly set of tapestries, now lost, depicting the clandestine erotic adventures of Jupiter (the Furti di Giove). The tapestry series was commissioned by Admiral-Prince Andrea Doria, ruler of Genoa and one of Perino’s major patrons, to hang in his newly erected palace on the outskirts of the city as a dazzling display of princely magnificence and cultivated taste.

The artist imagined the amorous composition as if seen through a window, complete with illusionistic framing elements lavishly decorated with classical detailing. The high degree of finish, lack of changes or revisions, and rich combination of media, as well as the large size and the inclusion of the surrounding borders and heraldic shield, suggest that this drawing was made as a presentation piece to show the patron. Perino was trained in Raphael’s studio in Rome, and absorbed the lessons of his master’s vocabulary (steeped in classical antiquity) into his own uniquely personal, elegant Mannerist style. This mature drawing of Jupiter and Juno, with its emphasis on extreme artifice, decorative grace, and effortless refinement, represents something of a culmination in Perino’s artistic career. It also more than proves his sheer technical virtuosity and capacity for extravagant invention.

(Carmen C. Bambach)’

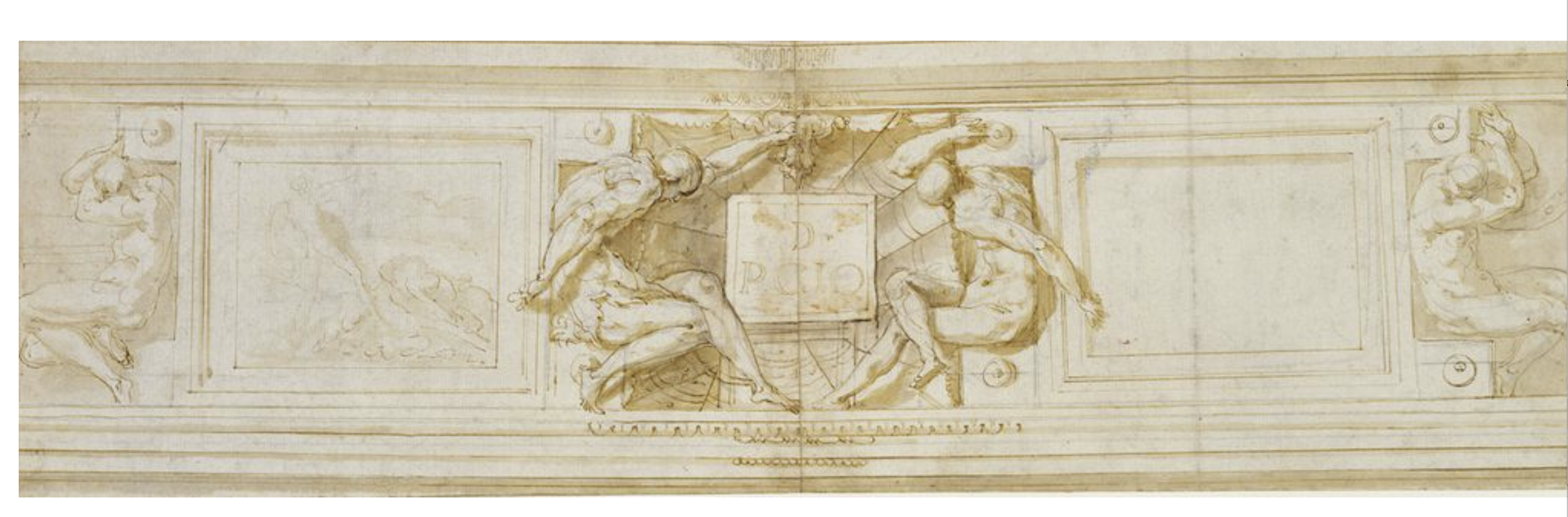

Perino del Vaga (1501-47), design for the decoration of a frieze, c.1537-40, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, 11.9 x 40.8 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 910902

‘The drawing is very similar in form and size to two others in Berlin (Kunstbibliothek, HdZ 417-18), published by Konrad Oberhuber as studies for a frieze in the appartamento piccolo of the Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne, Rome (‘Observations on Perino del Vaga as a draftsman’, Master Drawings, 1966, pp. 170-82). All three drawings show nudes crouching around fictive painted frames but they vary substantially in their details. In one of the Berlin drawings (HdZ 417) the ignudi support the architrave and crouch on blocks from which swags are suspended, spilling over a ledge supported on acanthus volutes. The other Berlin drawing is more elaborate still: the ignudi are replaced by wild-men and female satyrs standing on masks, and the rectilinear frame assumes the form of a cartouche. Only HdZ 417 closely with the frieze as painted. It is possible that they were drawn as alternatives of varying complexity for the patron’s consideration, an unusually clear example of the production of such modelli.

Perino’s work in the Palazzo Massimo was probably contemporary with his activity in the Massimi chapel of the Trinità dei Monti, between the end of 1537 (when Perino returned to Rome) and 1539, for the taste of the two schemes is very much the same (see a drawing in the V&A, Ward-Jackson 362). There seems to have been a campaign of decoration of the Palazzo Massimo at around this time: during modern restorations a panel bearing the date 1537 was uncovered in the ceiling of the Sala dei Ricevimenti. Oberhuber noted the importance of this type of Roman frieze-painting and its indebtedness to contemporary decorative work at Fontainebleau, with an interplay at differing levels of illusionism of figures, organic elements, blocks of masonry, picture-frames (both real and fictive) and narrative scenes; Perino himself was to use a very similar scheme a few years later in the Castel Sant’Angelo’.

Perino del Vaga (1501-47), design for an overdoor, c.1546-47, pen-&-ink and wash, 30.7 x 36.2 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 910761

This is a study for a fresco in the Sala Paolina, the principal room of the Castel Sant’Angelo decorated by Perino del Vaga and his workshop for Pope Paul III (Alessandro Farnese, r.1534-49).

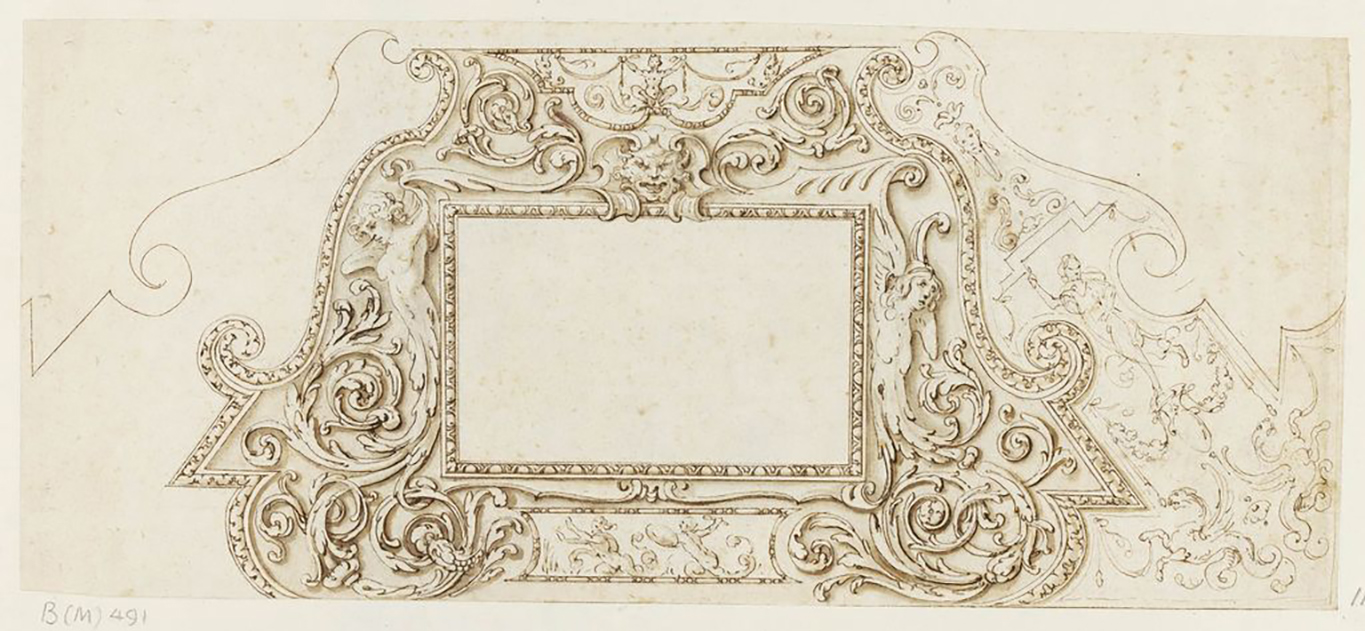

Perino del Vaga (circle of; 1501-47), vault decoration with dense scrollwork, c.1525-50, pen-&-ink, wash, 17.6 x 40.8 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 911340

‘The drawing shows one side of a pavilion vault, probably for a square room, containing a blank rectangular panel (for a figured scene) held by nude figures emerging from dense acanthus scrollwork, shaded to indicate that it was to be moulded in stucco. At the corners, in place of ribs, are curvilinear fields framed by volutes and shaped rather like balusters (see P. Davies and D. Hemsoll, ‘Renaissance balusters and the antique’, Architectural History XXIII, 1983, pp. 1–23), the right-hand one filled in with lighter (presumably painted) grotesque decoration. In a narrow field below the rectangular panel, probably also to be rendered in paint, a plant-man armed with a spoon-like weapon and shield chases a nude plant-woman fleeing to the left’.

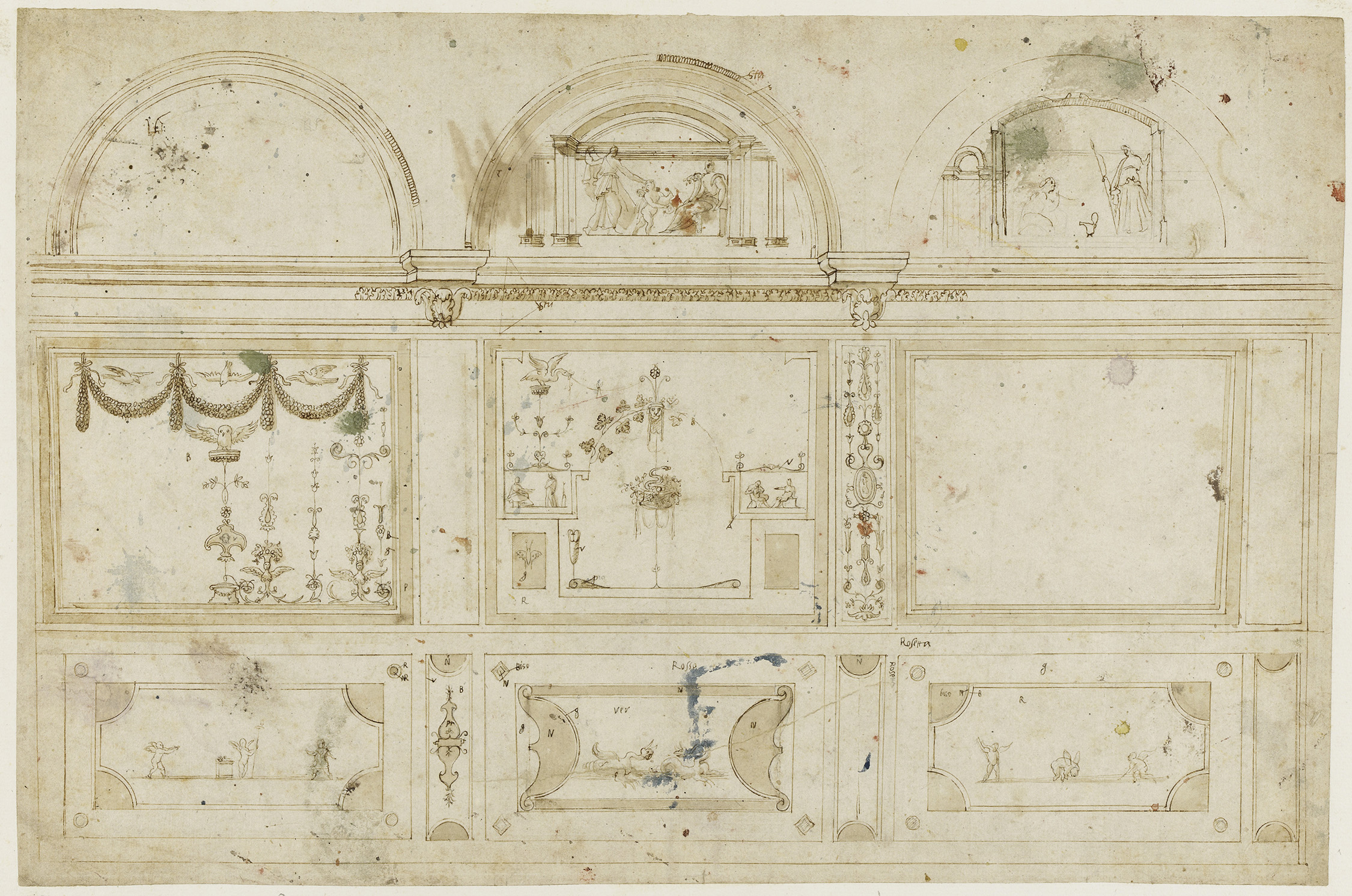

Perino del Vaga (circle of; 1501-47), wall decoration in grotesque style with lunette vault, c.1550, 28.4 x 43 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 970340

‘In this scheme for a wall beneath a lunette vault, three bays are shown divided into three horizontal zones in the conventional all’antica manner. The drawing lacks much of the detail, but all three levels of the central bay were evidently going to differ from their equivalents in the bays to the left and right. The latter both have the same panel design in the dado, each decorated with three putti playing, whereas the dado of the central bay has swans between pelta-shaped shields. In the middle zone of the central bay there is a snake in a hanging basket of flowers, a swan perched on a candelabrum (left) and a butterfly (bottom left). The equivalent panel in the left-hand bay has doves hovering in the loops of the garlands of the upper register and an owl with spread wings perched on a candelabrum. Lightly sketched in the central and right-hand lunettes are figures in colonnaded architectural settings, the central one composed of a putto between a heavily draped figure and a semi-draped seated male holding a cornucopia. The framing lines at the far right-hand edge imply that the scheme was to extend to at least one further bay in that direction. The scheme may also have been intended to continue further to the left too, since the perspective rendering of the two console capitals supporting the vault suggests that the midpoint of the scheme was somewhere close to the left edge of the drawing.

The present sheet is one of a set of ten drawings in Cassiano dal Pozzo’s miscellaneous Nettuno album closely related by subject matter and hands (RCIN 970340-9). All are designs for interior decorative schemes and all the work of either Luzio Romano (c.1510–90), a pupil and assistant of Perino del Vaga (1501–47), or other associates or followers of Perino.

Luzio, a native of Todi, had assisted Perino in his decoration of Palazzo Doria in Genoa (from 1528; see dal Pozzo A.X cat. 174; Steven and Jean Goldman Collection, USA; previously Stirling-Maxwell Sculpture album, fol. 104 (ii)) and was later extensively involved in Perino’s work on the Castel San Angelo in Rome (from 1545) and other commissions from Pope Paul III (reg. 1534–49). After Perino’s death he became one of Rome’s leading decorative artists in his own right, and was responsible for the decoration of Michelangelo’s Palazzo dei Conservatori (c.1575). For discussion of Luzio as a draughtsman, see S. Prosperi Valenti Rodinò, I disegni del Codice Resta di Palermo, 2007….

… Splashes of green, blue, mauve and red paint on the recto, and yellow, mauve, green and red on the verso, could suggest that the drawing was used during the actual execution of a scheme.

Annotations: stu (‘stucco’); s [?stucco] [x 2]; g(iallo) (‘yellow’) [x 3]; r(osso) (‘red’) [x 5]; b(ianco) (‘white’) [x 3]; rosetta (‘pink’) [x 2]; rosso (‘red’); ver(de) (‘green’); biso [= bigio] (‘grey’); n(ero) (‘black’) [x 3]; v(erde) (‘green’) [x 2]’

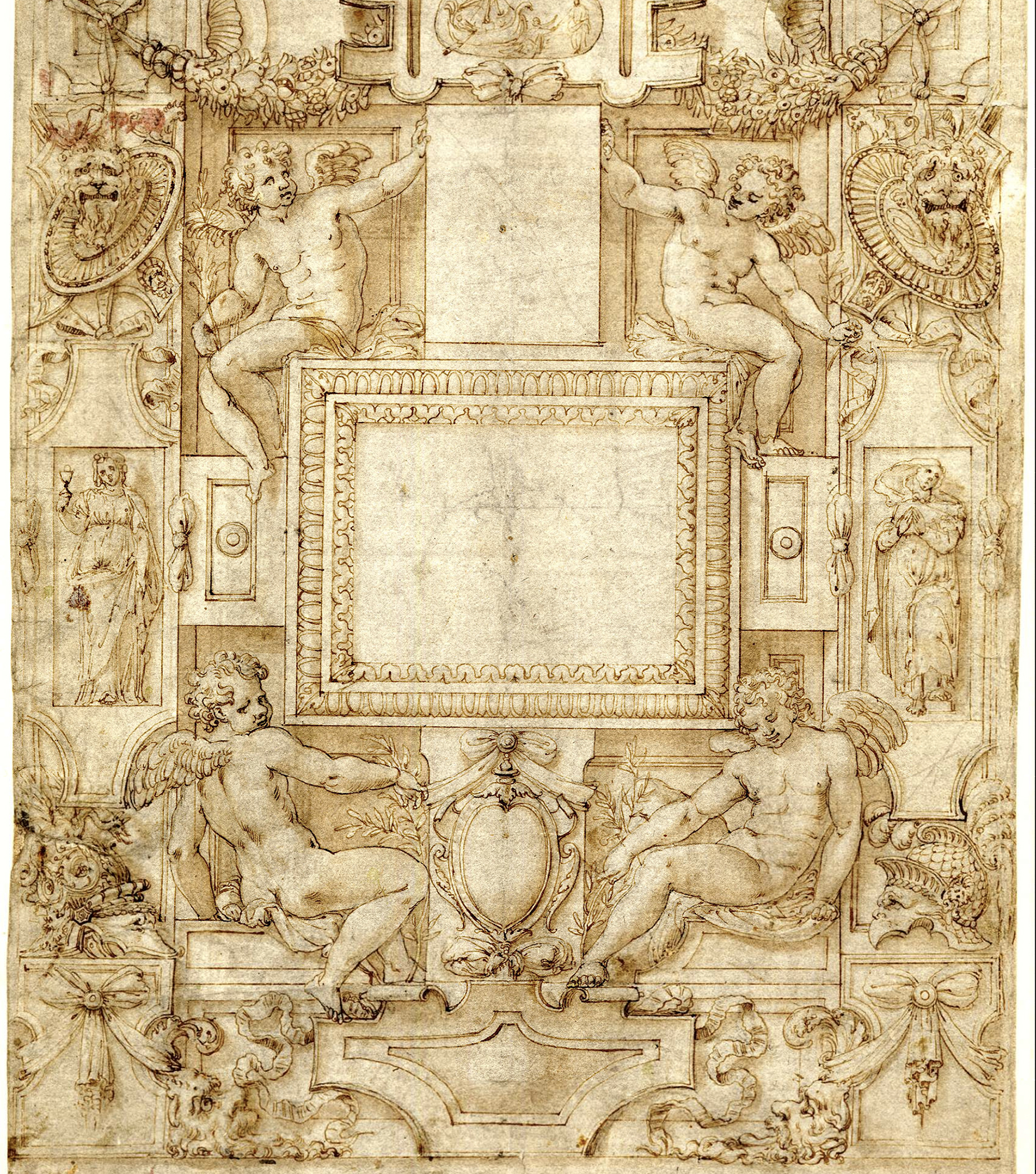

Perino del Vaga (studio of; 1501-47), design for ornamental panel, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, 38.2 x 28.2 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

‘… with central rectangular panel, flanked by putti above and below, shields mounted with lions masks, a draped woman at either side and grotesque masks below…

The drawing was unattributed when acquired, but Perino’s responsibility at least for the recto design is established by a black chalk sketch for the same project in Berlin (5166, as School of Michelangelo; Gernsheim 34453), inscribed in an old hand inside the larger rectangular space with an attribution to Raphael, but entirely characteristic of Perino in style and handling… 1874,0808.2 recto, though not from Perino’s own hand, seems to be a conscientious copy of a lost drawing by him.

Another such copy, corresponding in every detail but of somewhat inferior quality, is in the collection of the Royal Institute of British Architects, London (a 2/2, repr. R. Blomfield, ‘Architectural Drawing and Draughtsmen’, London, 1912, opp. p. 61) and two fragments of a third are in Berlin (25025)…. The archaic appearance of the head and shoulders in the upper rectangle in the Berlin sketch suggests that this is a design for a decoration framing some ancient and venerated painting. Vasari records two such projects by Perino. One, carried out some time before 1527, was the decoration of the altar wall of a chapel in S. Marcello al Corso embodying a painting of the Virgin ‘devozione in quella chiesa’; but the style of the Berlin sketch is considerably later… The second such project, datable some twenty years later, was for the embellishment, with ‘ornamenti di stucchi e di pitture’, of a ‘Madonna’ believed to be by Giotto which Perino and his friend Niccolò Acciaiuoli had been jointly instrumental in preserving during the demolition of old St Peter’s and in having transferred to a position ‘sotto l’organo‘ in the new basilica. An inscription by Acciaiuoli recording the transference and dated 1543 is now in the Vatican Grotte…’ (Forcella, vi, p. 69. no. 177)*. The image of the Madonna, and thus presumably also the stucco surround, were destroyed in the early 17th century…’

Perino del Vaga (studio/school of; 1501-47), Madonna & Child enthroned between a bishop and martyr, in decorated frame, pen-&-ink, wash, 29.6 x 18.9 cm., Albertina, Vienna

Northern Italian; the frame with God the Father (top cartouche), Ecce Homo (bottom cartouche), Annunciation (lateral centres), Evangelists in corners, saints in predella.

Polidoro da Caravaggio (c.1499-1543), design for an altarpiece, c.1527-28, pen-&-ink and wash with white, 25.8 x 20.5 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 990383

For Santa Maria delle Grazie alla Pescheria, Naples, demolished 1968.

Polidoro da Caravaggio (c.1499-1543), study for an architectural frieze, c.1525-30, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, black chalk, 16.4 x 25.9 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 910909

‘The dense detail of the upper moulding suggests that this was to be a particularly large and grand frieze. It is unfortunate that the artist neglected to complete the stemma in the left margin, which could have identified the family and thus probably the building for which it was designed; on the other hand this omission might suggest that the drawing was an exercise in invention, and not specific to any project.

P. Pouncey and J. Gere independently recognised Polidoro da Caravaggio as the author of this sheet (as recorded in Blunt 1971, no. 370), with his distinctively proportioned figures, busy outlines and rich inventiveness. The exuberance of the acanthus scrolls is comparable to the altar frame of c.1527 in RCIN 990383 [above], but it is hazardous to date such drawings by motif alone – the taste is equally that of Polidoro’s architectural-sculptural designs such as the friezes over the portals of Messina cathedral, and yet the drawing style retains more than a memory of Perino del Vaga’.

Polidoro da Caravaggio (c.1499-1543), studies for the figure of Christ, with the frame of a triptych, left, c.1530-35, pen-&-ink, 21.3 x 15.7 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

‘The centre and left-hand compartments of a triptych, the frame of which is surmounted by putti holding garlands… The majority of studies on 1918,0615.2 and 1936,1010.3 are related to a dismembered altarpiece in a triptych format with the Transfiguration at the centre painted by Polidoro in the first half of the 1530s for the main altar of the church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Messina in Sicily.

The altar was damaged in an earthquake in 1783 and taken apart and sold off, but its appearance can be reconstructed thanks to a detailed description in Susinno’s 1724 history of painting in Messina (quoted by Leone de Castris 2001, pp. 357-8), from which it is known that it was made up of six elements, the main part of which was the Transfiguration of Christ flanked by Moses and Elijah (by legend the founder of the Carmelite order); on the right of this was a life-sized image of St Angelus (a Carmelite with Sicilian connections, as he was martyred in the 13th century in Licata on the south coast of the island), and to the left St Albert of Trapani (the Carmelite patron saint of Messina). At the top of the altarpiece were three small compartments with a half-figure of God the Father and child angels on either side. At the base was a gusto antico (ie. pre-dating Polidoro’s work) painting of the Virgin suckling the Christ Child flanked by compartments with St Peter and St Paul on the right and left.’

Parmigianino (1503-40), a decorative scheme for the east vault, Madonna della Steccata, Parma, c.1531-39, pen-&-ink, wash, watercolour, 13 x 8.6 cm., V & A

Bartolommeo Neroni (c.1505/1510-71), design for an altarpiece with arched top, with Christ appearing to the Virgin, pen-&-ink, wash, traces of black chalk, partly squared for transfer, 38.2 x 26.3 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘Design for an altarpiece with, in the centre, Christ appearing to the Virgin, with saints John the Baptist, Francis and Jerome’.

Bartolommeo Neroni (c.1505/1510-71), design for an altarpiece with the Madonna & Child with saints, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, stylus, Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

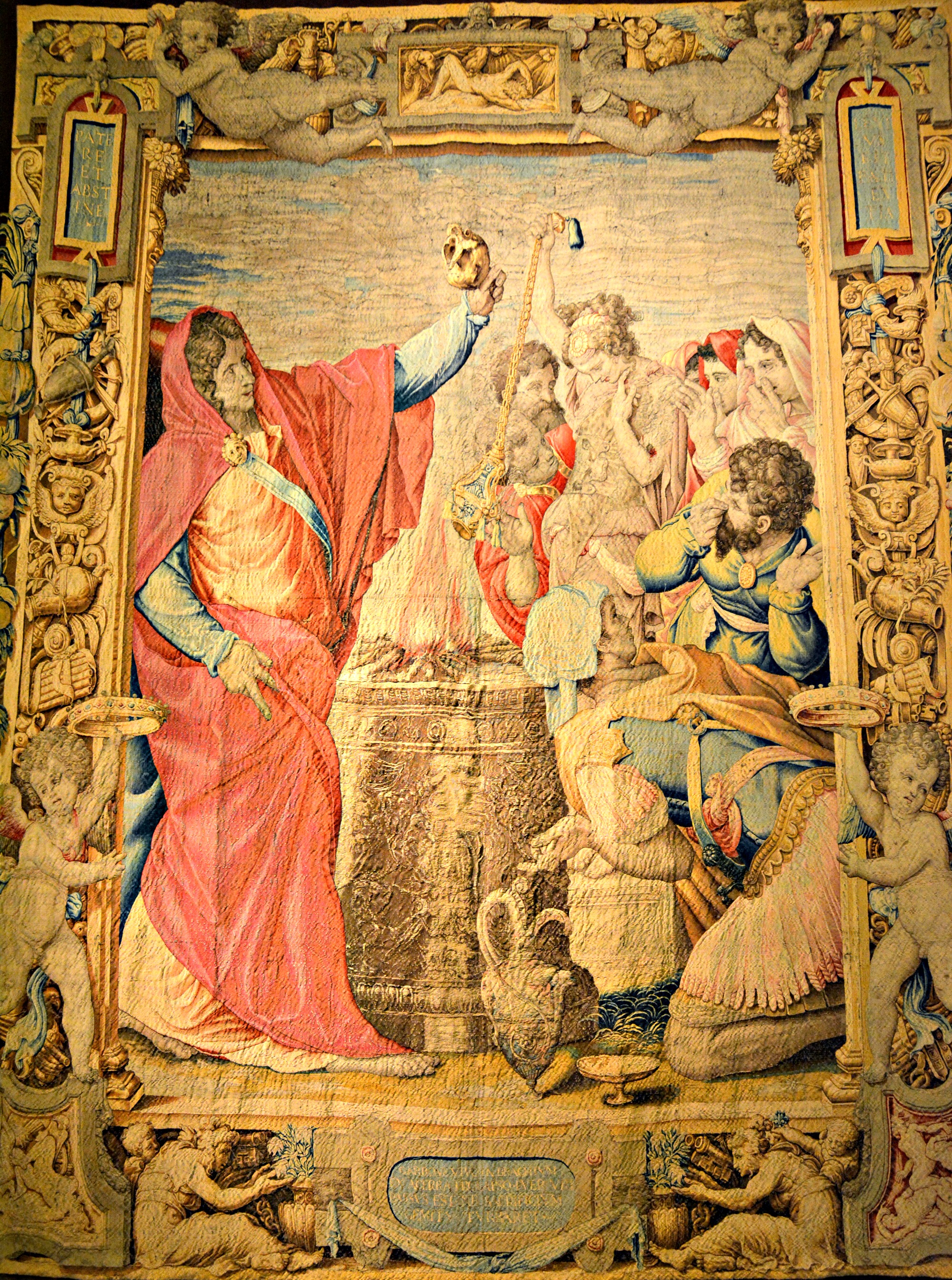

Francesco Salviati (or Rossi; 1510-63), design for a border for a tapestry with the Farnese arms, pen-&-ink, wash, heightened with white, 28.7 x 18.7 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

This drawing has been identified ‘… as a project for the border of the Sacrifice of Alexander, a tapestry in the collection of the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples’. Photo: Mentnafunangann

Prospero Clemente (1516-84), design for a tomb, c.1550, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, pricked, 50.2 x 30.4 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 910498

Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), design for an altarpiece or a tomb with a Madonna & Child, pen-&-ink, wash, traces of black chalk, 15 x 12.5 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), design for an altarpiece with The resurrection of Lazarus, and SS George and Mustiola, pen-&-ink, wash, traces of black chalk, 35.6 x 20 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

Inscribed on the predella panel:

‘EGO SUM RESURRECTIO ET VITA QUI CREDIT IN ME ETIAM SI MORTUUS FUERIT VIVET’.

‘Identified by A. Cecchi [Giorgio Vasari. Principi, letterati e artisti…, cat. exh., Arezzo, Casa Vasari, Sottochiesa di San Francesco, 1981, section IX, no. 1b] as a preparatory study for the altarpiece of the Vasari Chapel in Arezzo (Pieve di Santa Maria Assunta), thanks to the identification of the coats of arms of the Vasari family, on the left, and Vasari-Bacci, on the right. Cf. two preparatory studies for the same painting in the Galleria degli Uffizi, nos. 1189 E and 236 A recto. The design would be transformed into a free-standing, two-sided altarpiece for the high altar of the church. It is documented by a drawing in Hamburg (inv. 21512). The choice of the Resurrection of Lazarus is a tribute to the artist’s great-grandfather, the painter Lazzaro Vasari, to whom he symbolically attributed the rise of the family. (L. Frank & S. Tullio Cataldo, exhibition cat. Giorgio Vasari, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2011-12, no. 27)’.

Vasari (1511-74), Altare Mausoleo, 1563-64, with The calling of SS Peter, Andrew, James and John, 1551, Badia of SS Flora & Lucilla, Arezzo

The altarpiece was removed in 1865, and was recreated in the Abbey of SS Flora and Lucilla in Arezzo, where the top section is as originally built, whilst the lower part has been altered to fit its new setting.

Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), design for an altarpiece with The Last Judgement, c.1567/69, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, 73.5 x 44.5 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘This design – perhaps a page from the Libro dei disegni – is the largest surviving drawing by the artist. It is a study for the altarpiece, now dismembered, of the high altar of the church of Santa Croce in Bosco Marengo, Alessandria, commissioned from the artist by Pope Pius V and executed between 1567 and 1569. It is probably the modello submitted to the Pope, which C. Monbeig Goguel dated to the spring of 1567′.

The frame as constructed was of parcel-gilt poplar, decorated with walnut panels carved in relief with coats of arms and scenes from the life of Christ, which remain in the museum of Santa Croce or are elsewhere in the church. It was made in the workshop of Giovanni Gargioli.

Model of the Vasari altarpiece in front of an enlargement of the drawing above, Basilica di Santa Croce, Bosco Marengo. Photo: Artsupp

Although the architectural frame was removed in 1701, the paintings remain in the church and in the museum attached to it, where there is also a physical model of the altarpiece as it was, and access to a VR model of what Vasari called his ‘grand machine’.

Vasari (1511-74), The Last Judgement in its present-day frame, displayed in the apse, Basilica di Santa Croce, Bosco Marengo

The painting was given its current Baroque leaf frame in 1712-13; it was made of wood and stucco by Pietro Girolamo Chiara and Giovanni Santo.

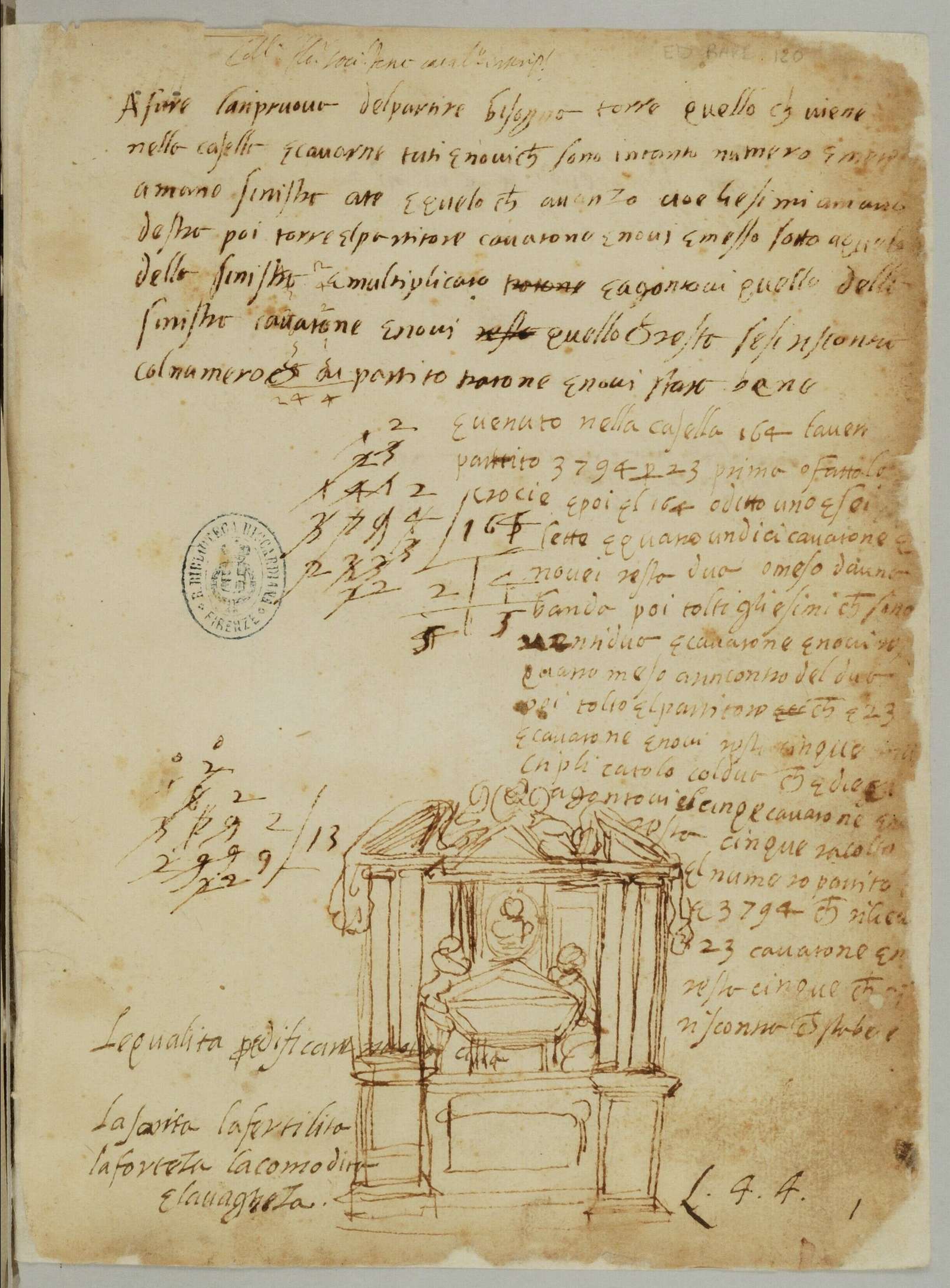

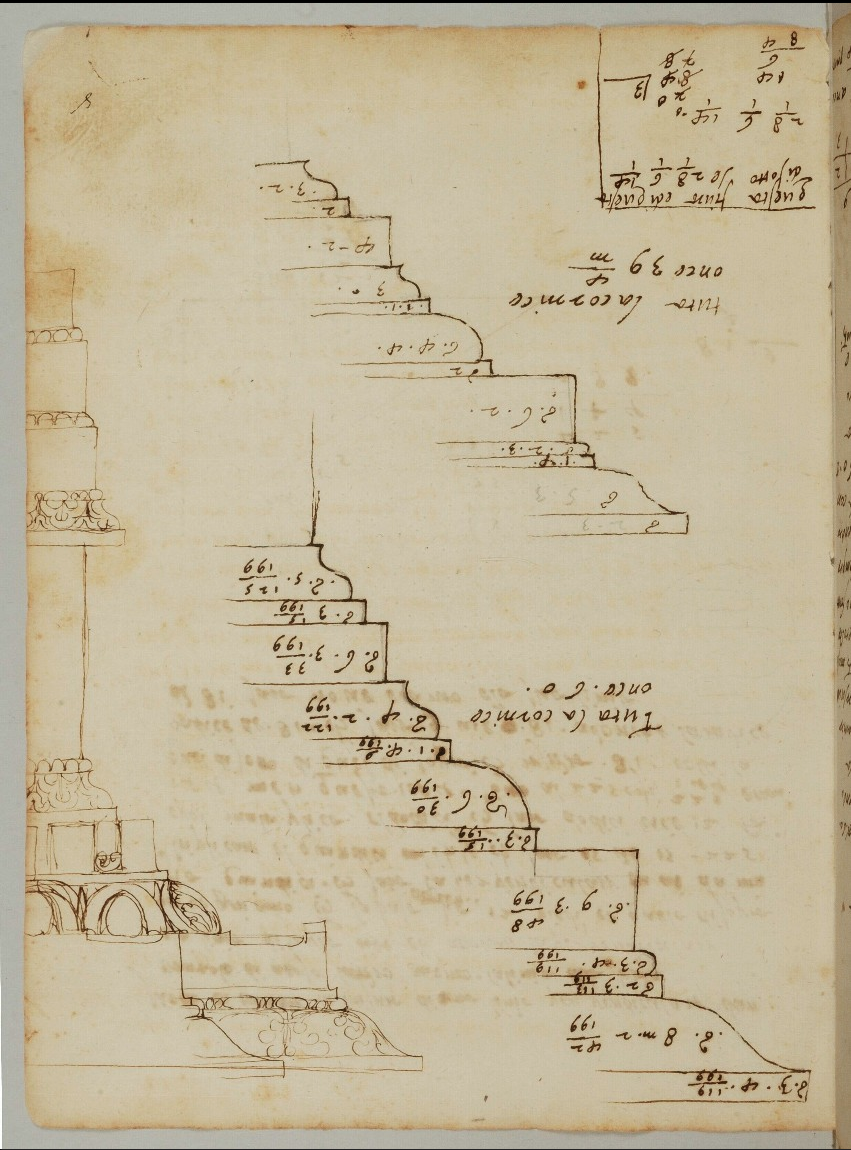

Bartolomeo Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook (Ed. rara 120), 1545-70, 1 recto, Biblioteca Riccardiana, Florence

As early as 1920, Enrico Rostagno attributed these folios – which had always belonged to the Riccardi family – to Bartolomeo Ammannati. They were put together during the 20th century, without following any precise chronological order. The drawings may be part of the section on theory in the volume (now at the Uffizi) known as The Ideal City.

There are 114 folios dating from 1545 to 1570, covered with drawings, sketches, and notes which address subjects as diverse as maths, geometry, architecture, studies on fortresses, and measurement systems. As a whole, they may serve as preparatory material for a fully-fledged treatise. In addition to architectural drawings (based on recognizable buildings, such as Vasari’s Uffizi Palace), the collection includes preliminary sketches of various objects, decorative studies, and statues which the author planned to make. The digital facsimile available through the Biblioteca Riccardiana has been realized in collaboration with the Museo Nazionale del Bargello.

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 8 recto

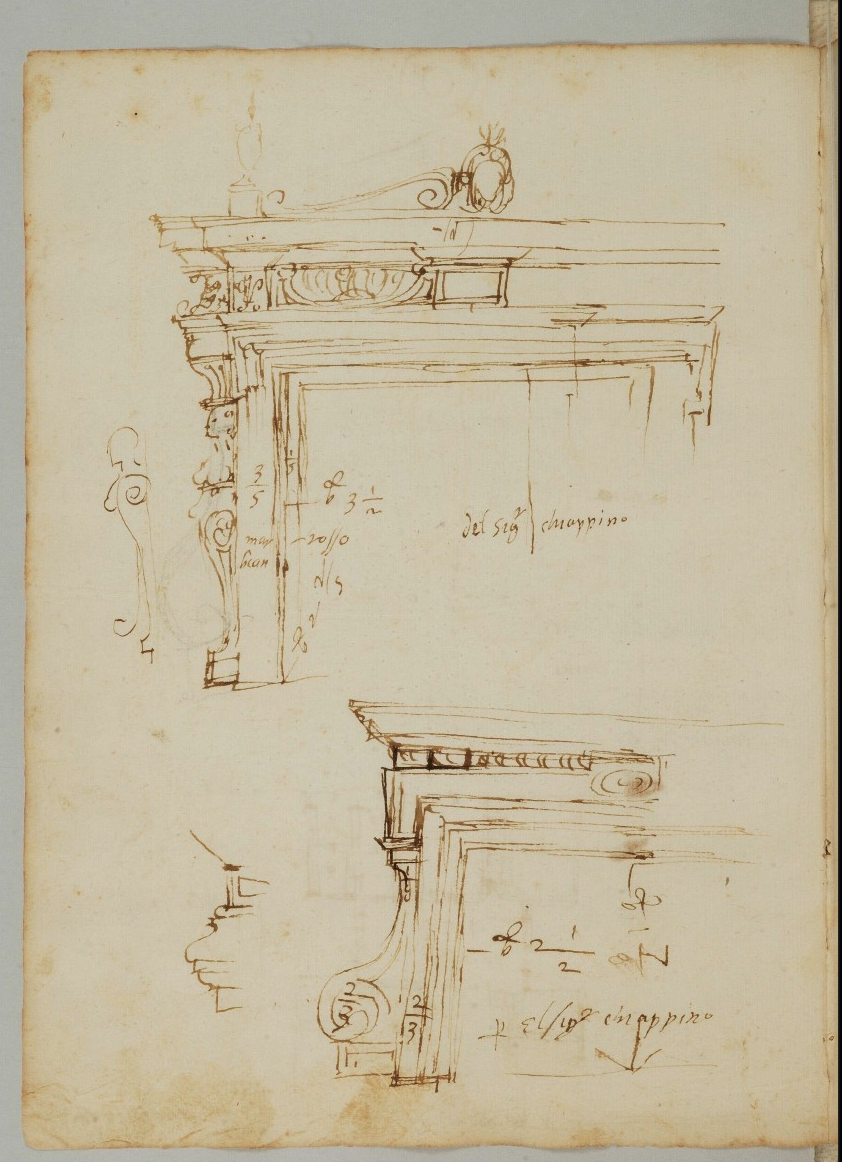

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 32 verso

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 34 verso

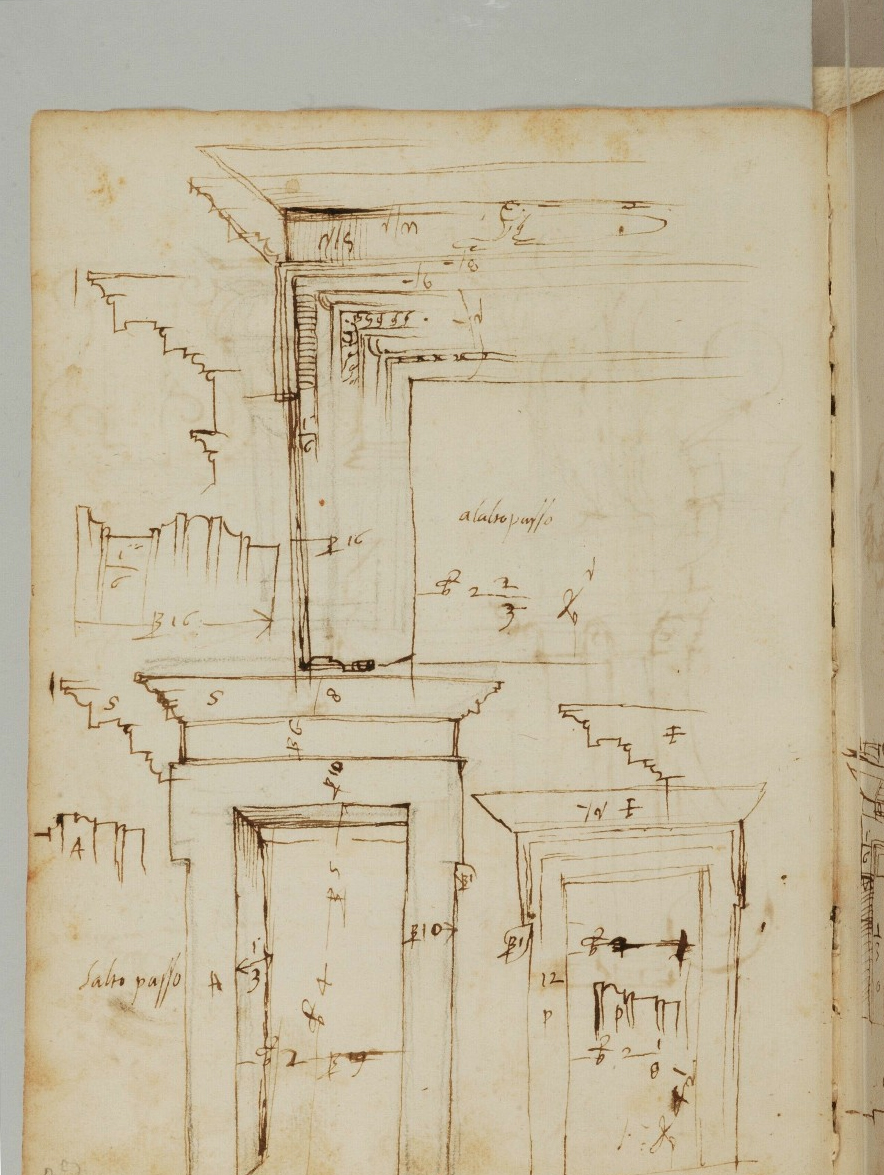

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 39 recto

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 39 verso

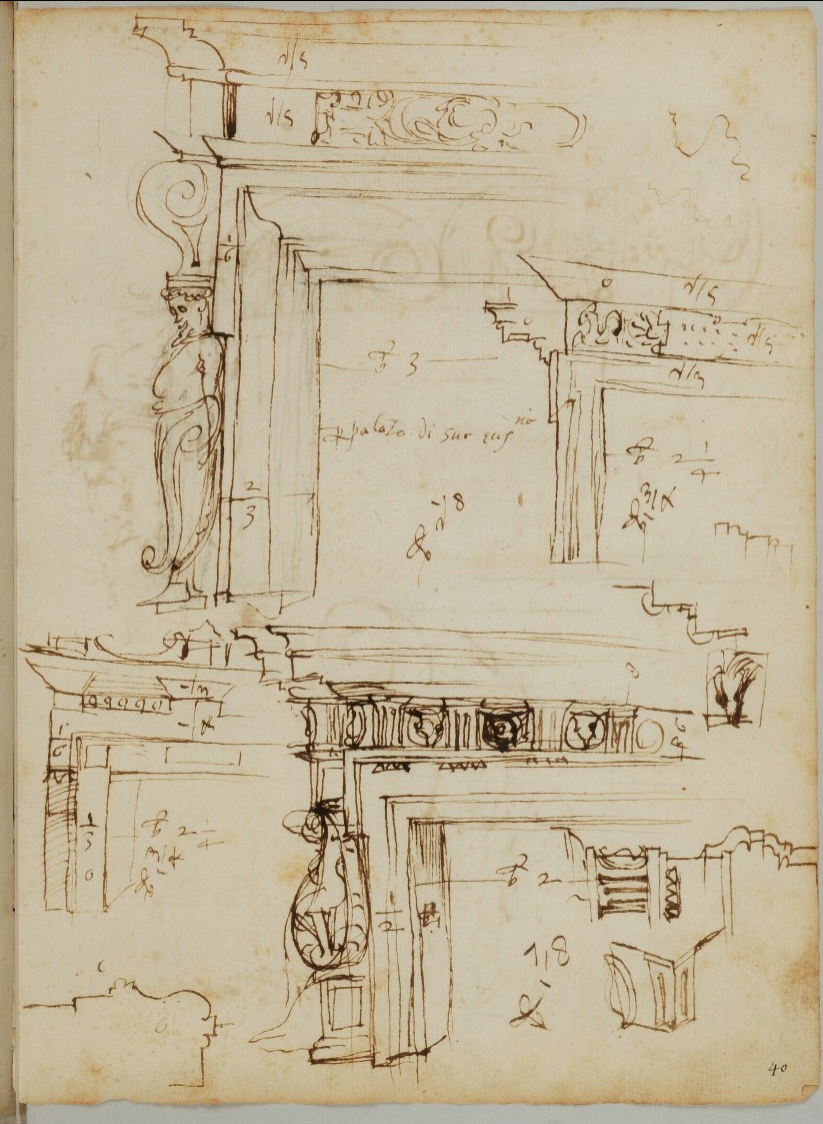

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 40 recto

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 40 verso

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 41 recto

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 41 verso

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 42 recto

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 42 verso

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 43 recto

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 43 verso

Ammannati (1511-92), sketch & notebook, 88 verso

Bernardino Campi (attrib.; 1522-91), The meeting of Joachim & Anna, c.1550, pen-&-ink, wash & white heightening, 41.4 x 23.9 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 990232

‘A modello for an altarpiece with its frame… Inscribed at bottom right in the ‘deceptive hand’: Giulio Campi. Inscribed on either side of an escutcheon underneath the frame: IO / BER.

Popham (in P&W) attributed the drawing to the young Bernardino Campi. Marco Tanzi (correspondence, 2006, 2018) suggested an attribution to Francesco Pesenti, associating the drawing with paintings by that artist formerly in San Pietro al Po, Cremona (now in S. Maria Assunta, Viadana), and on the altar of Giovanni Bertoni in San Leonardo, Cremona, commissioned in 1544. Certainly the composition style is that of Pesenti‘.

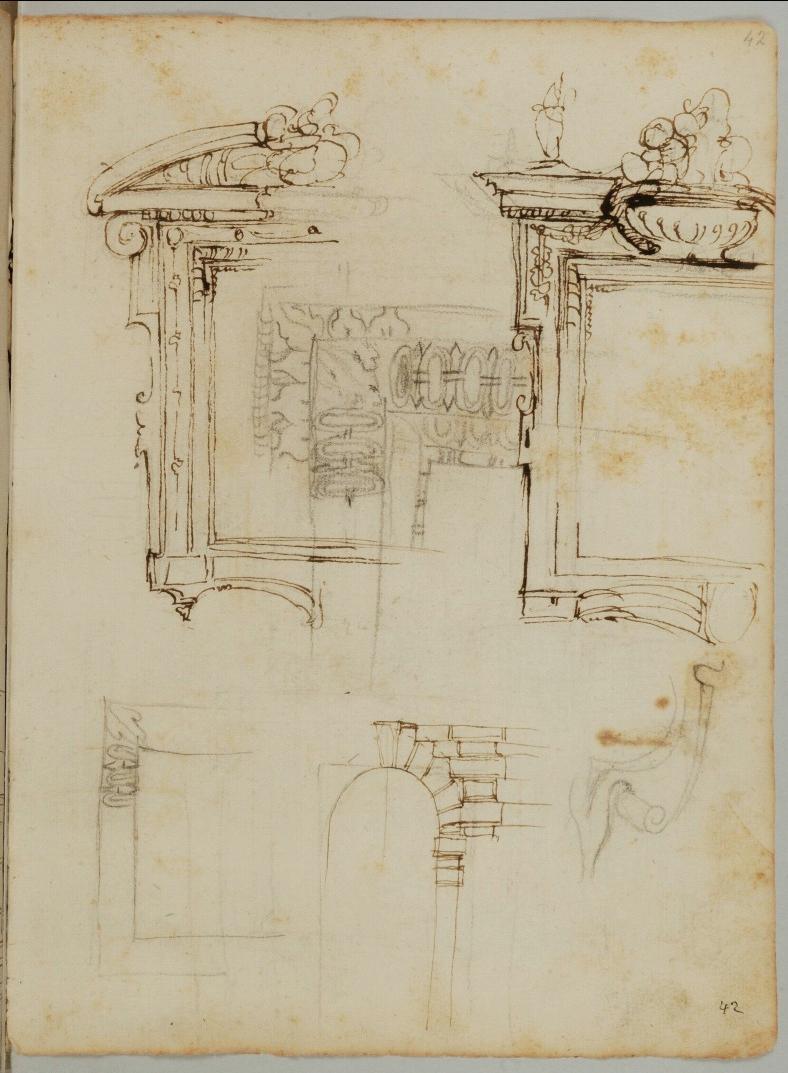

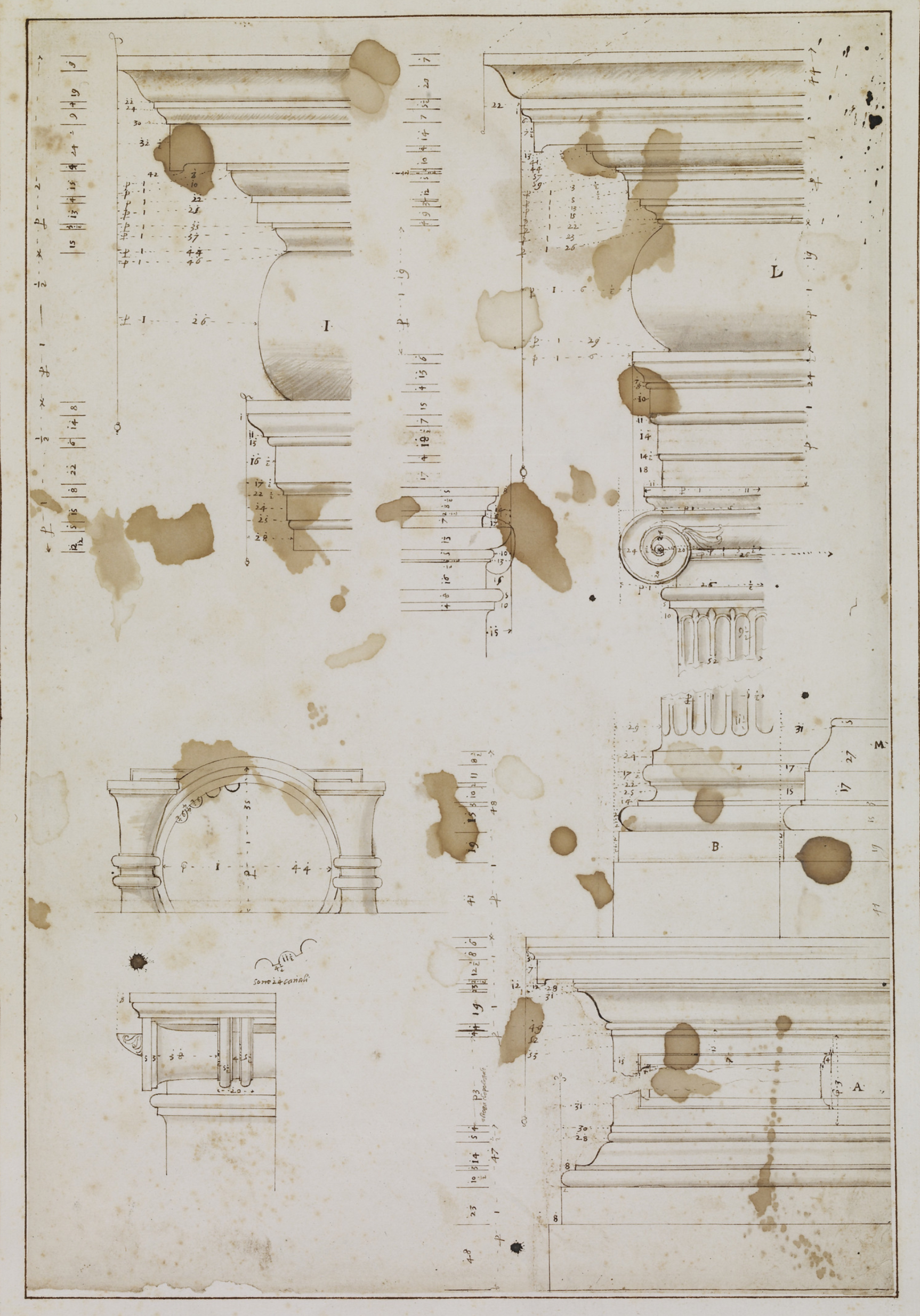

Daniele da Volterra (workshop; c.1509-66), Cappella Ricci, San Pietro in Montorio, Rome, details of design for main entablature & altarpiece frame, 1562-63, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, stylus lines, 41.9 x 28.5 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 910429

Daniele da Volterra (c.1509-66), The baptism of Christ, altarpiece, Cappella Ricci, San Pietro in Montorio. Photo: Peter1936F

‘A project drawing for the funerary chapel of Cardinal Giovanni Ricci in San Pietro in Montorio, Rome. Mounted in Cassiano dal Pozzo’s Architectura Civile album…

This sheet of drawings, all in orthogonal projection, gives detailed specifications for the architectural stonework of the chapel. At top left is the main entablature, keyed I, which runs round the chapel’s interior. All the others relate to the central Ionic tabernacle. At top right, keyed L, are its entablature and the upper part of the Ionic column, with a detail of the Ionic pilaster to the lower left. At bottom right are the base of the column and the pilaster, keyed B, and upper and lower mouldings of the tabernacle pedestal, keyed A. At bottom left are two additional views of the Ionic capital of the pilaster, its plan from below and in side elevation. Between these last two is a small detail of the fluting at the foot of the shaft, giving dimensions for the fillets and flutes (those at the neck are given in plan on the underside of the capital)’.

Vincenzo de’ Rossi (1525-87), design for an altarpiece: four different views, 1546-47, pen-&-ink, wash, traces of black chalk, 57.3 x 42.6 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘Whilst known principally as a sculptor today, early written sources suggest that Vincenzo de’ Rossi (1525-87), the successful pupil of Baccio Bandinelli (1488-1560), also had a career as an architect. This newly discovered drawing by the artist, acquired by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013 as an anonymous Florentine design, more satisfactorily substantiates the references found in the 16th century sources (Vasari 1568, and Borghini 1584) and sheds new light on Vincenzo’s activities as a draftsman and architect. The sheet, which depicts a comprehensive design for an altar and is inscribed and signed by the artist at bottom right ‘Vincentio Rossi’, can be considered the first genuine architectural drawing by his hand to surface. It is almost certainly connected to an early and prestigious commission for the altar of the Confraternita dei Virtuosi in the Pantheon, Rome, commissioned from the artist in 1546.’

Luca Cambiaso (1527-85), an architectural study for the interior of a chapel with a statue, pen-&-ink, wash, 61 x 42.7 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘This drawing recalls the architectural designs produced by Giovanni Battista Castello and Luca Cambiaso between 1550 and 1565: in fact, it is close to Castello’s Design for an altarpiece with Christ enthroned, in the archives of Genoa, and to Luca Cambiaso’s Design for an altar with the Virgin and saints in the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin. The composition is similar to that of a ceiling with niches framing allegorical figures on the second floor of the Palazzo Gio Vincenzo Imperiale, a work created in collaboration by these two artists. (F. Mancini in exhibition cat. Luca Cambiaso, Paris, Louvre, 2010-11, no. 15)’.

Garofalo (attrib.; 1481-1559), Two winged putti supporting an escutcheon, mid-16th century or later, pencil, ink, wash, white heightening, 6.5 x 10.3 cm., Museo del Prado

Luzio Luzi (fl.1528-75), designs for wall & vault grotesque decorations, c.1550-75, pen-&-ink and blue wash, 32.8 x 31.4 cm., Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 970344

‘A scheme for grotesque wall and vault decorations, one of a set of ten drawings in Cassiano dal Pozzo’s miscellaneous Nettuno album closely related by subject matter and hands (RCIN 970340-9, for further comment see 970340).

‘This scheme was for the decoration of a wall and its related vault, probably a barrel vault: although the diagonal decoration leading to a rectangle at the centre might suggest a pavilion vault, it does not lead to the rectangle’s corner as is required in such a vault. On the wall (the lower half of the drawing), framing a tabernacle (perhaps a window), is a large panel of grotesque designs incorporating spread eagles in the upper register and putti below. Alongside is a narrower field containing a panelled plinth on which stands a youthful Cupid, flanked by two male nudes in Phrygian helmets (Castor and Pollux). Above Cupid’s head, on fronds springing from a vase, are two partridges and above them two peacocks framing a fleur-de-lis. On the vault (the upper half of the drawing) a broad band of grotesque decoration involving masks, sphinxes and rampant felines surrounds a large rectangular frame at the vault’s centre, probably to be filled with a figurative painting’.

Lelio Orsi (1511-87), frame for an altarpiece, 1530-87, pen-&-ink, brown wash, 49.6 x 35.4 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

‘The pilgrim’s staves and shell in the pediment show that the altarpiece was intended for a church or chapel dedicated to St James the Greater’.

Giulio Campi (attrib., c.1502-72; or circle of Polidoro da Caravaggio, c.1499-1543), design for an altarpiece with the Madonna & Child, SS Peter and Paul, 1517-72, Cremonese or south Italian, pen-&-ink heightened in white, 49.2 x 30.2 cm., © Trustees of the British Museum

‘Although kept under the name of Campi the influence of Polidoro da Caravaggio suggests it is more likely by a southern Italian artist’.

Giovanni Battista Ramenghi (Bolognese; 1521-1601), design for an altarpiece with the Madonna & Child adored by a martyred saint and St Petronius, pen-&-ink, wash, heightening in white, traces of black chalk on the frame, 39.5 x 24 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

Bernardino India (1528-90), design for a wall decoration with Grimani coat of arms, second half 16th century, pen-&-ink, wash, 16.5 x 31.3 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘This design for a wall decoration or a façade [over an archway] depicts four female figures around the arms of the noble Venetian family of Grimani. From left to right, the figures may be identified as allegorical representations of Magnanimity (or Venice Triumphant), Justice, Peace, and Constancy. Executed in pen and ink, brush and brown washes, it is a typical example of the draughtsmanship of Bernardino India, who was particularly receptive to the Mannerism emanating from Mantua (Giulio Romano) and Parma (Parmigianino).’

Martino Rota (Dalmatian; c.1520/32-1582/83), Profile bust of an armoured man, pen-&-ink, wash, traces of transfer, 14.4 x 12.6 cm., Albertina, Vienna

Marco Marchetti (pre-1528-1588), design for a wall decoration, including the coat of arms of a Grand Duke of Tuscany, c.1561-88, pen-&-ink, wash, traces of black chalk, 23 x 32.7 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘Design for a wall elevation with a fireplace and door opening. Over the chimneypiece is a panel with Apollo and the Muses, and over the door frame a sculpted coat-of-arms of the Grand Duke of Tuscany as Grand Master of the Order of Santo Stefano. In between, the personification of Astronomy is depicted in a niche, a decoration which was most likely meant to be executed in fresco.’

Pellegrino Tibaldi (1527-96), study for the decoration of the Escorial Library, 1588-92, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, 33.2 x 48.5 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

Inscribed with notes by Juan de Herrera (architect of the Escorial from 1567-93).

‘ Though in itself of little artistic value, this drawing, with its annotations in Italian by the artist responsible for the decoration, and in Spanish by the architect of the building and by an unidentified court official, is of considerable documentary interest as affording a glimpse of the complicated process by which a great decorative enterprise of this kind was brought to completion…

The Greek-key pilasters support flat strips of the same pattern, which separate all the bays except the second and third and the fifth and sixth. Between these is a more complex arrangement dividing the whole space into two end-sections of two bays and a central one of three, and consisting of a tripartite arch, the centre member of which is a projecting strip of Grotesque ornament springing from similarly decorated piers, with on either side narrower and shallower strips of ribbon-and-foliage decoration supported on Greek-key pilasters. A band of Grotesque ornament on the vault adjoins the inner side (that is, the side towards the centre of the room) of this tripartite arch, between the inner ribbon-and-foliage strip and the Greek-key strip bounding the adjacent bay; another band of Grotesque ornament, between two Greek-key strips, divides the two bays in either end section. Immediately above the cornice, on all four bands of Grotesque ornament as well as on the centre members of the two arches, are figures of Gods or Poets in niches; on all the Greek-key strips, roundels with seated figures in yellowish-brown monochrome; and on all the ribbon-and-foliage strips, similarly coloured upright rectangles with standing figures…

…1846,0509.176 does not correspond with any particular section of the decoration, but is made up of elements which occur in various bays. So far as we can tell from the illustrations of the Library at our disposal, each element (except presumably the composition in the frieze) corresponds exactly with the finished work.’

Pellegrino Tibaldi (1527-96), design for half a frame with mascarons and grotesques, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, squared up in black chalk, 20.7 x 9.9 cm., Gallerie degli Uffizi

The catalogue entry for this notes that this drawing has not yet been linked to a realized work; it connects the motifs and style to work carried out under the leadership of Prospero Fontana in the Palazzo Silvestri Rinaldi and the Villa Giulia in Rome, and to a drawing by Tibaldi for the arms of Cardinal Poggi in the Louvre, amongst other studies.

Pellegrino Tibaldi (circle of; 1527-96), design for a wall elevation with grotesques, c.1540-70, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, 38.9 x 26.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘This design shows a decoration for a niche between two pillars, which is filled by a so-called candelabrum ornament with male and female satyrs… Grotesques became a popular motif for wall decorations during the last quarter of the 15th century. They were based on the murals found in the partly excavated Domus Aurea (Emperor Nero’s Golden House, c.64 AD)… The theme of this wall decoration is particularly licentious and was most likely designed for the private quarters of a city palace.’

Giambologna (1529-1608), Study for the altar wall of the Salviati Chapel, c. 1580, no. 237A, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampi degli Uffizi, Florence

Maso da San Friano (1531-71), design for an altarpiece fresco of the Resurrection, 1560-71, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, black chalk, 28.1 x35.1 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘This lunette seems to have been intended as an altarpiece, and as a fresco. It is placed asymmetrically within the austere, crypt-like bay of a chapel, and rests above a base with projections, the central one of these appearing to be an altar. Beyond the frame of the altarpiece is a kneeling figure of a female monastic saint on the left. She is echoed on the right by a kneeling un-haloed matron. The latter may well be a figure relating to the patron of the fresco…

… the design of the Metropolitan sheet was presumably intended for a funerary chapel, given the subject of the main picture, which is apparently conceived of as a fresco.

(Carmen C. Bambach, 2007)’

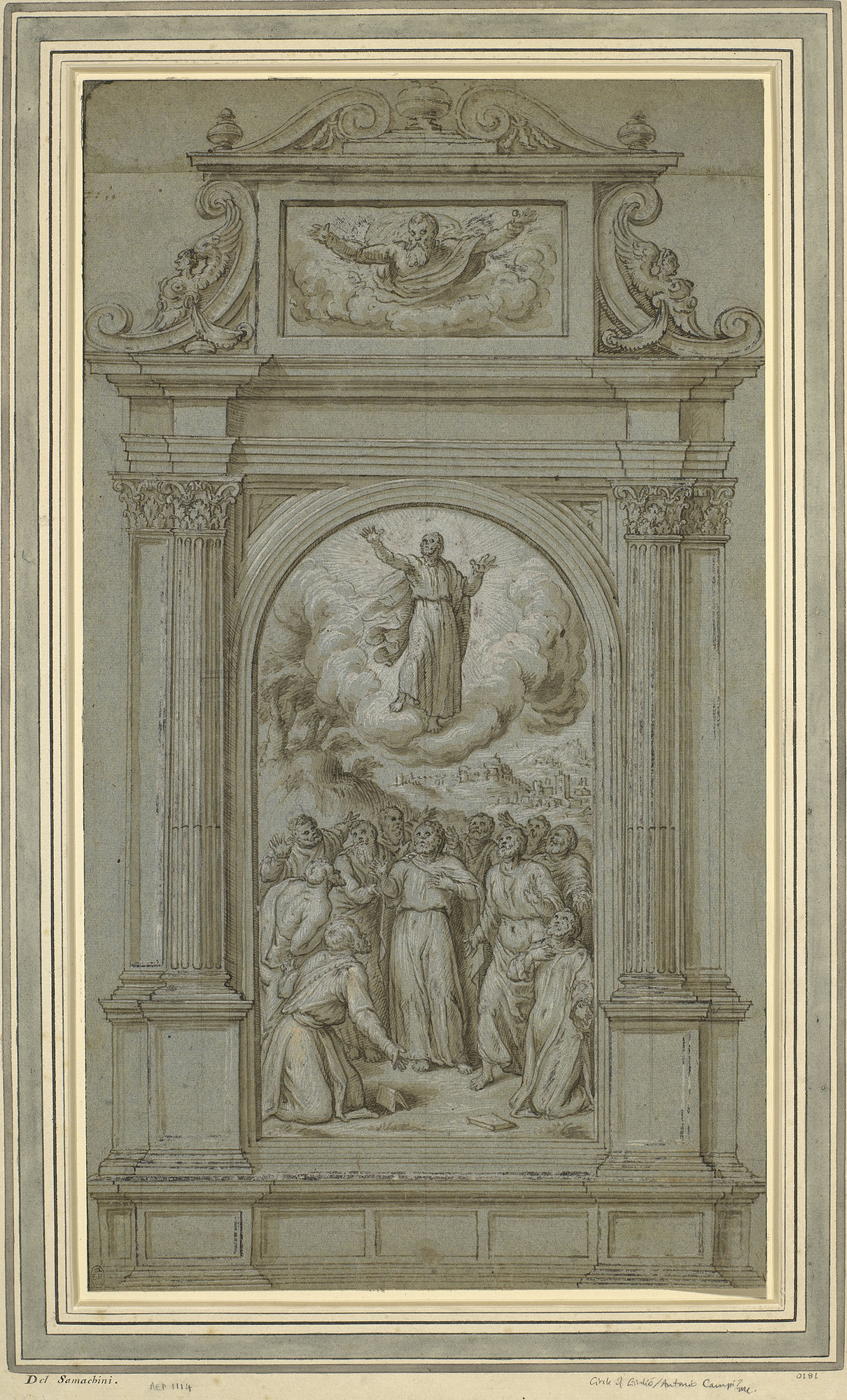

Orazio Samacchini (1532-77), study for the decoration of a vault, c.1570, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, 39.1 x 25.5 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Vault of the north transept of the Duomo, Parma, with frescos by Orazio Samacchini, c.1570

Giovanni de Vecchi (1536-1615), architectural elevation of an interior with two clerestory windows, second half 16th century, pencil, ink, wash, white heightening, 22.5 x 16.3 cm., Museo del Prado

‘This is an entirely characteristic work of Giovanni de’ Vecchi. The two imprese, in the panel´s lower centre, which might otherwise provide evidence as to the church the decoration was designed for, are, alas, indecipherable.’

Federico Zuccaro (1539/40-1609), decorative scheme for a chapel dedicated to the Virgin, pen-&-ink, wash, 28.6 x 42.8 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘The altarpiece, The assumption of the Virgin, is framed by smaller scenes, including the Death of the Virgin and the Apostles interring the body of the Virgin‘.

Federico Zuccaro (1539/40-1609) or possibly Cristofano Roncalli, decorative scheme for a chapel dedicated to the Virgin, c.1566-72, pen-&-ink, wash, 11.3 x 14.4 inches, V & A

‘This drawing, which shows a pentagonal chapel with a semi-domed ceiling, can be approximately dated from the coat of arms over each door. It is that of Pope Pius V (Ghislieri) who reigned from 1566 to 1572. Also above the two doors are statues of SS Peter and Paul, and on the left, a scene of the Flight into Egypt. This drawing was once thought to be by Federico Zuccaro or Cesare d’Arpino, but it is possible that it might be by Cristofano Roncalli’.

Federico Zuccaro (1539/40-1609), design for a Quarantore, last third 16th century, pen-&-ink, wash, white heightening, traces of black chalk, 38.9 x 28.5 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘This detailed presentation drawing offers a design for a temporary structure erected for a devotion of Quarent’ Ore or Forty Hours. The host was continuously adored for forty hours, reflecting the time between Christ’s death and his Resurrection. As seen in the drawing, the host lay in a casket or sarcophagus placed on a temporary structure in a side altar or chapel. This liturgical practice, which probably originated in Milan, became common during the second half of the 16th century as a formal plea for intercession in times of danger or calamity. It is still practiced, although with changes, in the Roman Catholic Church today.’

Cristoforo Roncalli (known as Pomarancio; 1552-1626), frame: pen-&-ink, wash, oval portrait: pen-&-ink, Holy Family: chalk, 29.1 x 20.8 cm., Albertina, Vienna

The frame decorated in the corners with signs of the zodiac; in the centres with emblems of day, night, sea, and land; and with figures of the four Evangelists.

Carlo Urbino (1553-85), design for the decoration of the façade of a chapel, third quarter 16th century, pencil, chalk, ink, wash, 21.5 x 30.6 cm., Museo del Prado

‘The Prado drawing has been squared for transfer, either to a small-scale modello or to the actual-sized cartoon, suggesting that the design may have been realized.’

Antonio Tempesta (1555-1630), frame on Federico Zuccari’s Induction of a cardinal, picture: pen-&- ink, wash, white heightening, squared up in chalk; frame: chalk, pen-&-ink, wash, 43.2 x 26.7 cm., Albertina, Vienna

Ludovico Carracci (attrib.; 1555-1619), design for a frame for the portrait of an elderly man, Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 910777

‘An oval medallion surmounts a decorative cartouche & is supported on either side by the figures of Justice and Charity while the figure of Fame flies above’.

Ludovico Carracci (1555-1619), Saints & angels in adoration on border for drawing of Virgin by Parmigianino (1503-40), Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 902336

‘Two saints, one of them St John the Evangelist, & a choir of angels by Lodovico, form the surround for a small drawing of the Virgin carrying a crucifix by Parmigiano. Squared but no corresponding altarpiece is known’.

Cherubino Alberti (possibly attrib.; 1553-1615), sketches of architectural details, late 16th century, pen-&-ink, black chalk, 46.4 x 33.6 cm., Fondation Custodia

‘Recto: Sketches of a vase, a crucifix, some putti and cherubs’ heads and architectural details. Verso: Engraving by Cherubino Alberti after Taddeo Zuccari, The Conversion of Saint Paul.

Cherubino Alberti (1553-1615), Beheading of St John the Baptist, c.1591, pen-&-ink, wash, traces of black chalk, 25 x 28.5 cm., Romano Fine Art Gallery, Florence

‘…in the sheet which we present here, the artist is captured at work… finding different solutions… and finally erasing the parts which he is not sure of, such as the two eagle heads drafted in the centre of the piece and redrawn more definitely at the centre of the frame. The outer border, typical of the decorative exuberance of Cherubino, is similarly expressed in other drawings by the artist, such as in the Portrait of Henri IV, king of France. Alberti tries different solutions: on the left, the body of the eagle is finished with an acanthus curl within which appears a little male head; on the right this is transformed into the foot of the bird of prey clawing at the edge of the frame. The imaginative zoömorphic invention expressed in the frame, as well as the restless line which outlines it, show a clear dialogue with the Roman works of Perino del Vaga, a painter whom Cherubino Alberti always regarded with profound admiration.’

Agostino Carracci (1557-1602), mascaron (head of a satyr) in a garland frame, pen-&-ink, 18.1 x 13.4 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘Probable design, not realized, for the interior of the Tazza Farnese; commissioned by Odoardo Farnese. A drawing closer to the final composition is preserved in the British Museum…’ and there are three others in Windsor, Washington and Stockholm.

See also Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), The drunken Silenus, a design for the Tazza Farnese, 1599-1600, Met Museum, New York (below).

Antonio Vassilacchi (1556-1629), study for a processional standard with the Madonna & Child, 1583, pen-&-ink, wash, black chalk, 41.4 x 30.7 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

‘…beneath an architectural canopy supported by pillars, surrounded by a decorative frame with symbols of the four evangelists at the corners and the Annunciation in the middle’.

‘… A contract drawing for a processional banner for a Venetian confraternity (Scuola), a related study with a more elaborate version of the composition is in the Louvre, Paris (illustrated Meijer fig. 3). The latter drawing has, like the present work, a contract on the verso dated 13 December 1583 with the artist agreeing to execute the painting in accordance with the drawn study.

The Louvre drawing has the same two saints, one a soldier and the other a bishop, adoring the Virgin and Child as in the BM design but instead of the symbols of the Evangelists at the corners of the standard as they are in the London work they are shown as full-size figures at the four corners of the elaborate altarpiece-like frame enclosing the central group. The refinement of the Paris drawing is in keeping with the greater sophistication of composition, and the contract states that the artist was to receive 80 ducats compared with 50 for BM design. The patron of the two works is not known, although Meijer suggests that if the warrior saint is Theodore it might have been executed for the Scuola Grande.

Another processional banner design for the same Scuola, possibly also by Vassilacchi, was sold at Bassenge, 1 December 2001, lot 5230 as Florentine School 1550/60 (this was offered for sale at Sotheby’s, 5 July 2006, lot 9 as ‘Attributed to Antonio Vassilacchi’)…

Designs for processional standards by other Venetian artists include an unfinished example with the Pietà in Copenhagen (Meijer, fig. 35) and one in the Albertina (V. Birke and J. Kertész, ‘Die Italienischen Zeichnungen der Albertina’, I, Vienna, 1992, no. 434, p. 244 as follower of Perino del Vaga). The Vienna drawing has somewhat similar imagery and may be for the same church or scuola as the BM/ Louvre sheets. It is closest to the London drawing with a border with four saints (not the Evangelists) at the corners and in oval compartments at the centre of each side with God the Father (top), and the Annunciation (left and right). The lower one is filled with an Ecce Homo while in the BM this space taken up with a Pelican, a symbol of Christ’s Passion. The two saints adoring the enthroned Virgin and Child could be the same as one is a youthful warrior in armour, and the other is a bishop. A drawing in the BM (1900-7-17-32) attributed to Girolamo Santacroce (Tietze and Tietze Conrat, no. A 1401, pp. 246-7) is also for a banner. Watermark: a shield with device.’

Lodovico Cardi (1559-1613), Florentine, design for an altarpiece, pen-&-ink, wash, black & red chalk, white heightening, 42.6 x 26.6 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

‘F. Viatte connects it with the carved wood altarpiece of the church of the Capucines de Montughi, near Florence (cat. exp. ‘Dessins baroques florentins du Musée du Louvre’, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 1981-1982, n°14)’.

Lodovico Cardi (1559-1613), Florentine, design for an altarpiece, pen-&-ink, blue wash, black & red chalk, white heightening, 40.7 x 26.8 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

Connected by A. Matteoli to the design ‘… for The Adoration of the Magi made by Cigoli for the church of San Pier Maggiore in Florence (now at Stourhead House, Wiltshire), which [he] dates from the artist’s stay in Rome (1604)’.

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), Self-portrait in a frame, early 1580s, pen-&-ink, 13.5 x 10.8 cm., J. Paul Getty Museum

‘…Skeletal beasts with beaked heads and long necks peer down from the upper corners [of the frame], reminders of mortality, and two beady-eyed dolphins with tails in the air inhabit the bottom corners.

Carracci portrayed himself humorously here as a scruffy, ordinary individual. In a format usually reserved for formal, flattering portraits, he demonstrated his ability to pick out the most important, expressive features quickly. In a display of originality, he leans forward out of the picture frame as if from a window.

Francesco Maria Niccolò Gabburri, who assembled numerous drawn self-portraits and portraits of artists, once owned this sheet. He also owned the Getty Museum’s Self-portrait by Gaetano Sabbatini, which shares the oval format. This drawing remains laid down on the original Gabburri mount, but it has been cut down drastically’.

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), Studies for a section of architectural decoration (possibly Galleria Farnese?), 1597-1601, pencil, ink, wash, 48.9 x 38.1 cm., Museo del Prado

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), Drunken Silenus, design for the Tazza Farnese, 1599-1600, pen-&-ink, wash, traces of black chalk, 25.6 x 25.5 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘This final, highly finished demonstration drawing is for a standing silver cup or salver (the Tazza Farnese), for Annibale’s patron Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, and is one of the only signed drawings by the artist. The Tazza Farnese is no longer extant. A silver plaque (Museo Nazionale, Naples), probably a copy rather than an original piece from the Tazza, was rediscovered in 1955. It was apparently used for printmaking, and pulls from it were taken from a fairly early date onward. Two other studies by Annibale for this silver plaque have survived (British Museum, London, and Art Institute of Chicago [formerly in the Ellesmere collection]), and represent earlier stages of the design. With respect to the Naples plaque, the present drawing reveals only minor changes.

Annibale produced a number of preparatory sketches for the Farnese cup, including this one, in which the border is incised for transfer. The figural scene is not incised, and some changes are evident in the print that records the finished design…’

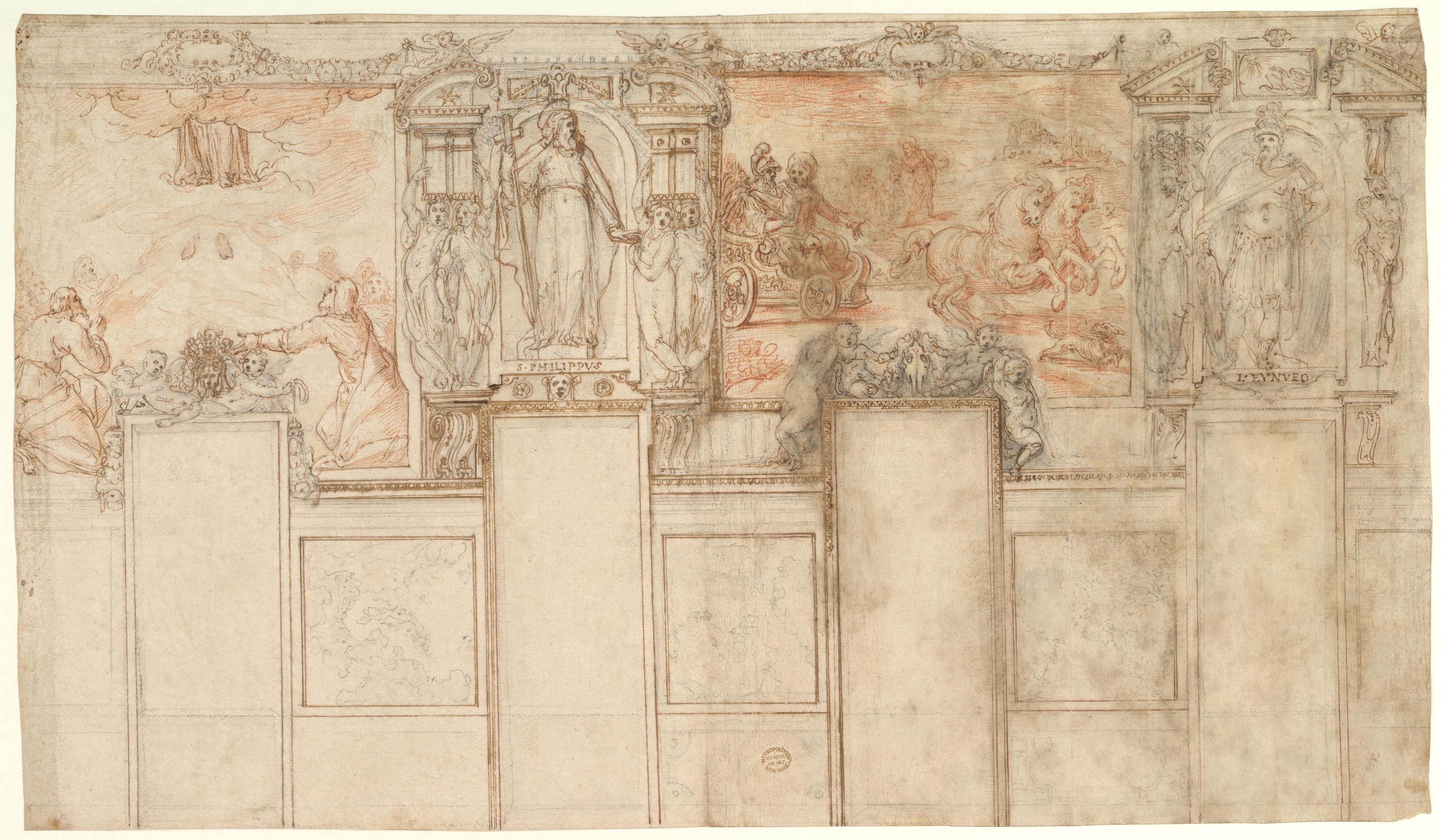

Giovanni de’ Vecchi (1536/37-1615), design for a wall decoration, c.1600, pen-&-ink, black chalk, red chalk, 31.3 x 54.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

‘The ‘bretessed bend’ and the stars of the Aldobrandini arms which appear above the figure of St Philip could identify this project as a never-executed scheme commissioned by or proposed to Pope Clement VIII Aldobrandini, who reigned from 1592 to 1605.’

Bernardo Castello (1557-1629), design for an altarpiece, with the Madonna & Child between SS John the Baptist and Benedict, last quarter 16th century-first quarter 17th century, pencil, ink, wash, 35.1 x 21.6 cm., Museo del Prado

‘This drawing is of particular interest since it shows an artist furnishing the design for his painted altarpiece, along with a scheme for the position of the altar it was intended for – the top of which is indicated by the Maltese cross seen in perspective – and its architectural frame. The altarpiece, which is capped by an open pediment, is set within a tablet which breaks forward from the Ionic pilasters and cornice to which it attached. At the top of the structure, in the space left at the centre of the open pediment, is a figure of the Infant Christ as Salvator Mundi…

Castello presumably submitted the drawing to his ecclesiastical patrons for their approval and his presentation of the whole scheme almost certainly indicates that he would have had charge over the construction of the entire monument, not just the painting of the sacra conversazione which forms its decorative focus. The utilitarian purpose of the study explains the unadorned, schematic quality of the drawing. Unfortunately, it is not clear whether this particular altar was destined for a private chapel within a church or whether it was merely to be positioned against the nave wall of such a church. The presence of St Benedict standing on the right within the altarpiece design would appear to indicate that the altarpiece was destined for a monastery church of the Benedictine Order, the oldest Western monastic Order.’

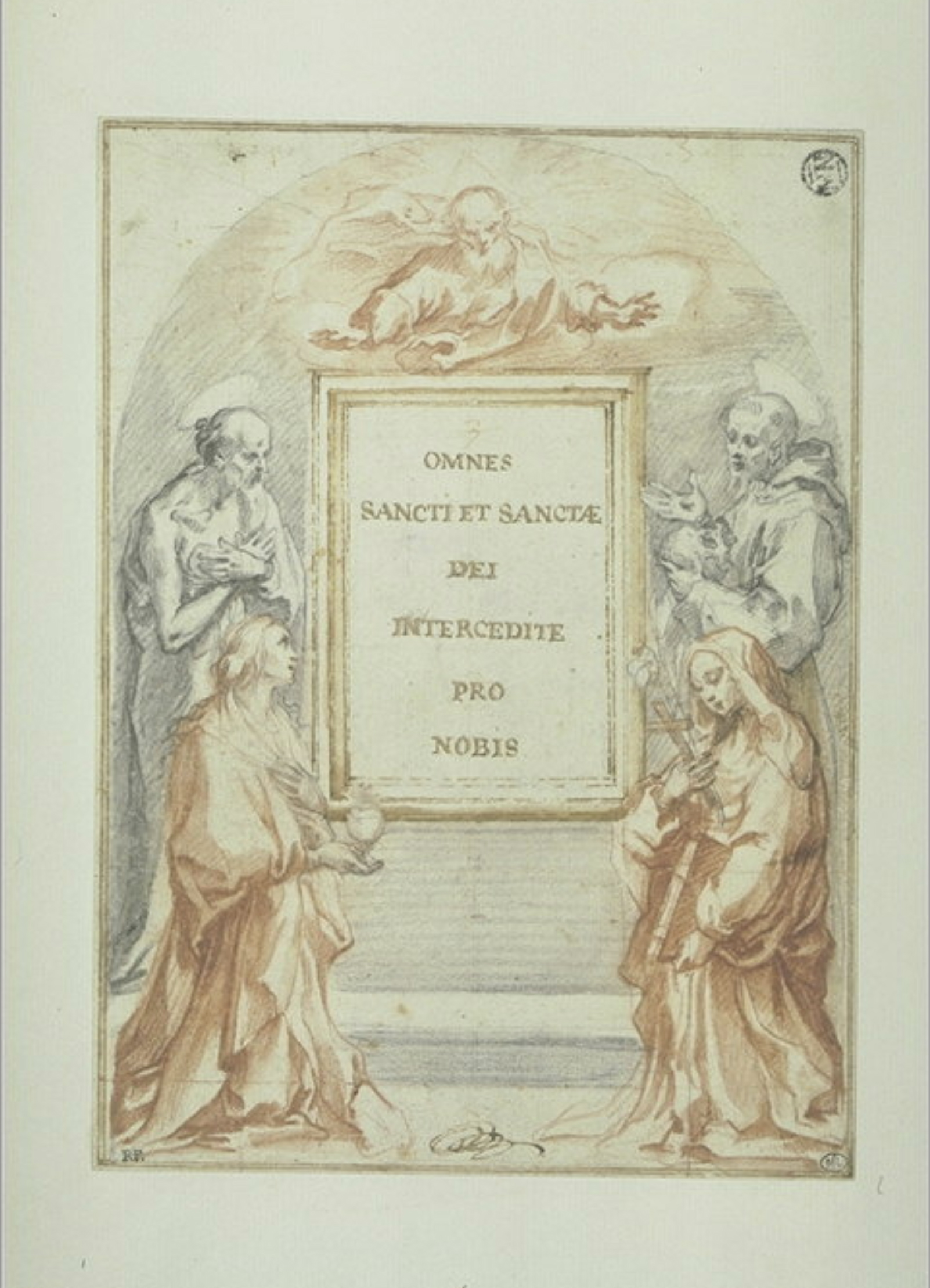

Francesco Vanni (1563-1610), design for an altarpiece with God and four saints surrounding a frame, sanguine, black chalk, wash, 22 x 16 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

The saints are SS Jerome, Francis, Catherine of Siena, and Mary Magdalen. Inscribed in the middle of the frame,

‘OMNES / SANCTI ET SANCTAE / DEI / INTERCEDITE / PRO NOBIS’.

This was almost certainly one of the 5,000 drawings which were sold to Louis XIV in 1671 by the collector, Everhard Jabach, from an even larger number in his possession.

Muzio Oddi (1569-1639), Altar of San Paolo alle Tre Fontane, Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 910014

‘… showing the outline of the altarpiece with its architectural frame composed of two flanking Corinthian half columns supporting a heavy cornice and semi-circular pediment…’

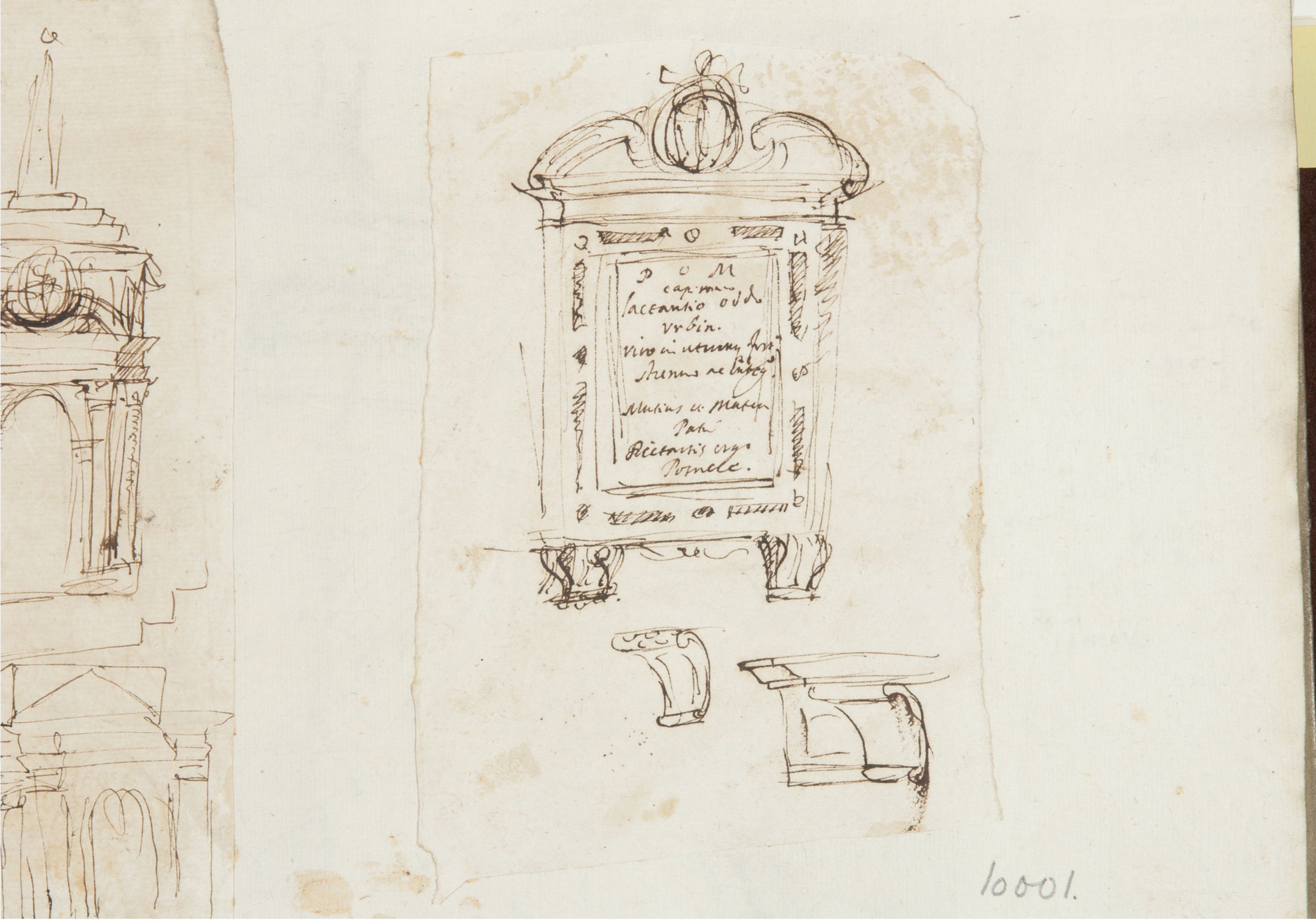

Muzio Oddi (1569-1639), design for an epitaph, with the architectural frame and the mouldings in profile beneath, Royal Collection Trust. RCIN 910001

Muzio Oddi (1569-1639), design for a fountain (left) and a chimneypiece (centre), with mouldings (lower right), Royal Collection. RCIN 910002

Rafaello Schiaminosi (attrib.; 1572?-1622), Four saints, end 16th-beginning of 17th century, pencil, ink, wash, white heightening, 19 x 24 cm., Museo del Prado

‘Schiaminossi was a Tuscan engraver and painter and a follower of Raphael (1483-1520) and the Sienese Ventura Salimbeni (1568-before 1613). The style of this drawing seems however to be Roman, from the circle of the Zuccari, and is somewhat suggestive of that of Avanzino Nucci (1551-1629) and Giovanni Alberti (1558-1601).’

Anon., 16th century Italian school, design for an ? altarpiece, with the Madonna & Child, and angels placing Christ in the tomb, end of the century, pen-&-ink, wash, stylus, 27.1 x 24.8 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre

Anon., Lombard school, design for an altarpiece dedicated to the Virgin & St George, pen-&-ink, wash, 40.8 x 27.6 cm., Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre