Framed crucifixes. Part 1: conserving an Italian Calvary

Introduction

This is the first of a pair of articles on the small but important category of framed domestic crucifixes, which may have begun in Italy with altarpieces like the one featured here, and which produced – from the late 17th century onwards – an especially striking class of French crucifixes with shaped frames.

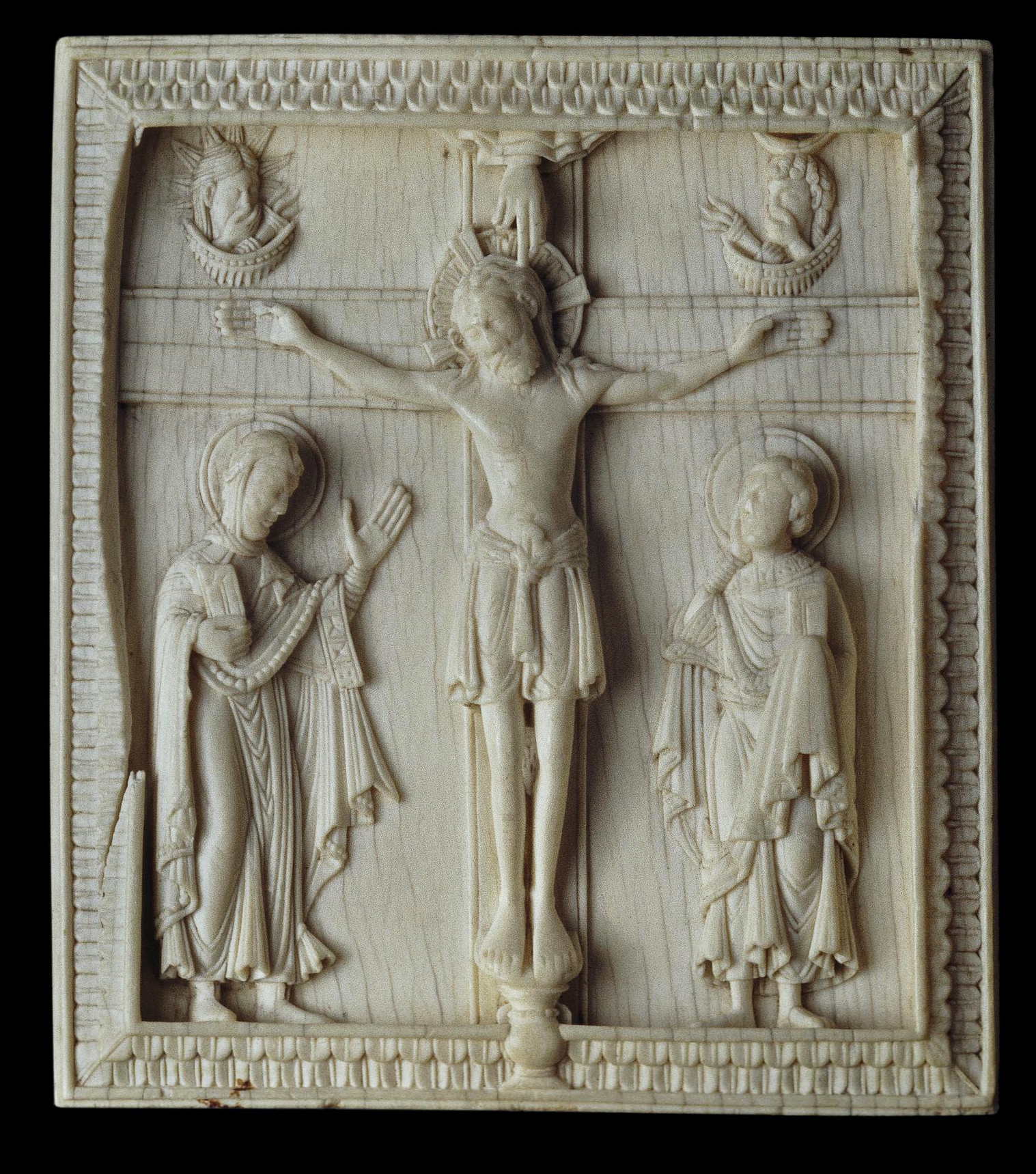

Belgian School (Liège?), integral framed panel with crucifixion scene, c.1100, walrus ivory, 11.5 x 10.1 cm., © The Trustees of the British Museum

They unite the large wall-hung crucifix, early rood screen crucifix, framed relief sculpture in marble and stucco, domestic painted altarpiece, and carved ivory crucifixion for individual devotion (above), and they may have arisen from the simple practicality of preserving a relatively small-scale sculpture from damage and dust, after the fashion of the Spanish guardapolvos – the decorated, canted boards protecting three sides of the vast, wall-sized retables which fill the east ends of so many churches and cathedrals in Spain. In the case of the crucifixion scene below, the frame provides an entire sheltering niche for the figures.

Part 1: conserving an Italian Calvary of c. 1600 in the Universalmuseum Joanneum, Graz, Austria

by Paul-Bernhard Eipper, Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova and Ulrich Becker

The altarpiece as displayed in 1898 in the newly-constructed building of the Styrian Landesmuseum Joanneum in Neutorgasse Graz. Photo: Anon/UMJ, c.1910

The rescue of a domestic altarpiece from the Museum’s storage demonstrates how fruitful it can be to engage with a less familiar item from the collection, and also to conserve it. In many places, scarce in-house staff are overburdened with expensive and temporary special exhibitions, which often obscure a view of the museum’s own holdings – the exact opposite of the current demand for sustainability. Changing the approach in favour of older, far too often neglected holdings is therefore more than necessary, since it’s not uncommon for real treasures to be awaiting rediscovery, as in this case. Why would local visitors not react positively to an unexpected revitalization of such objects in the museum? – remarking, ‘We didn’t even realize that this was here!’ Visitor statistics aren’t fed solely by tourists from elsewhere [1].

The Styrian State Museum (Kulturhistorisches und Kunstgewerbemuseum) © Kulturhistorische Sammlung, Museum für Geschichte

In 2021, an incorrectly inventoried Italian altarpiece from the late Renaissance was found in an external store. This small-scale domestic altarpiece had been acquired in 1898 for the ‘Kunstgewerbliche Mustersammlung’, or collection of decorative arts, where it was on permanent display in the newly completed building in Neutorgasse until the ‘Kirchliche Abteilung’ – ecclesiastical department – was separated from it, and integrated instead into the ‘Landesbildergalerie’ (the Styrian State Picture Gallery) in 1910. After the Second World War, it was somehow forgotten about.

Italian Calvary in aedicular frame, 16th-17th century, with 19th century additions; boxwood and walnut; backed with coloured velvet; condition before 2022. Photo: Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova; Paul-Bernhard Eipper

This domestic altarpiece, carved from walnut and boxwood, represents the scene of the crucifixion – a dramatically moving group, set within the principal round-arched niche, whilst the triangular pediment contains the figure of God the Father. As well as the crucified Christ, the figures include the Good and Bad Thief, the Virgin, St John and Mary Magdalene, sited on the rocky top of Mount Calvary. Dismas, the ‘Good Thief’, hangs on a cross on Christ’s right, and Gestas, the ‘Bad Thief’, on His left, turns away – as is conventional – from his Saviour. The composition is well-balanced and symmetrical. The sculptural quality of the figures and expressive dynamism of their clothes contrast with the classical geometry of the architectural frame.

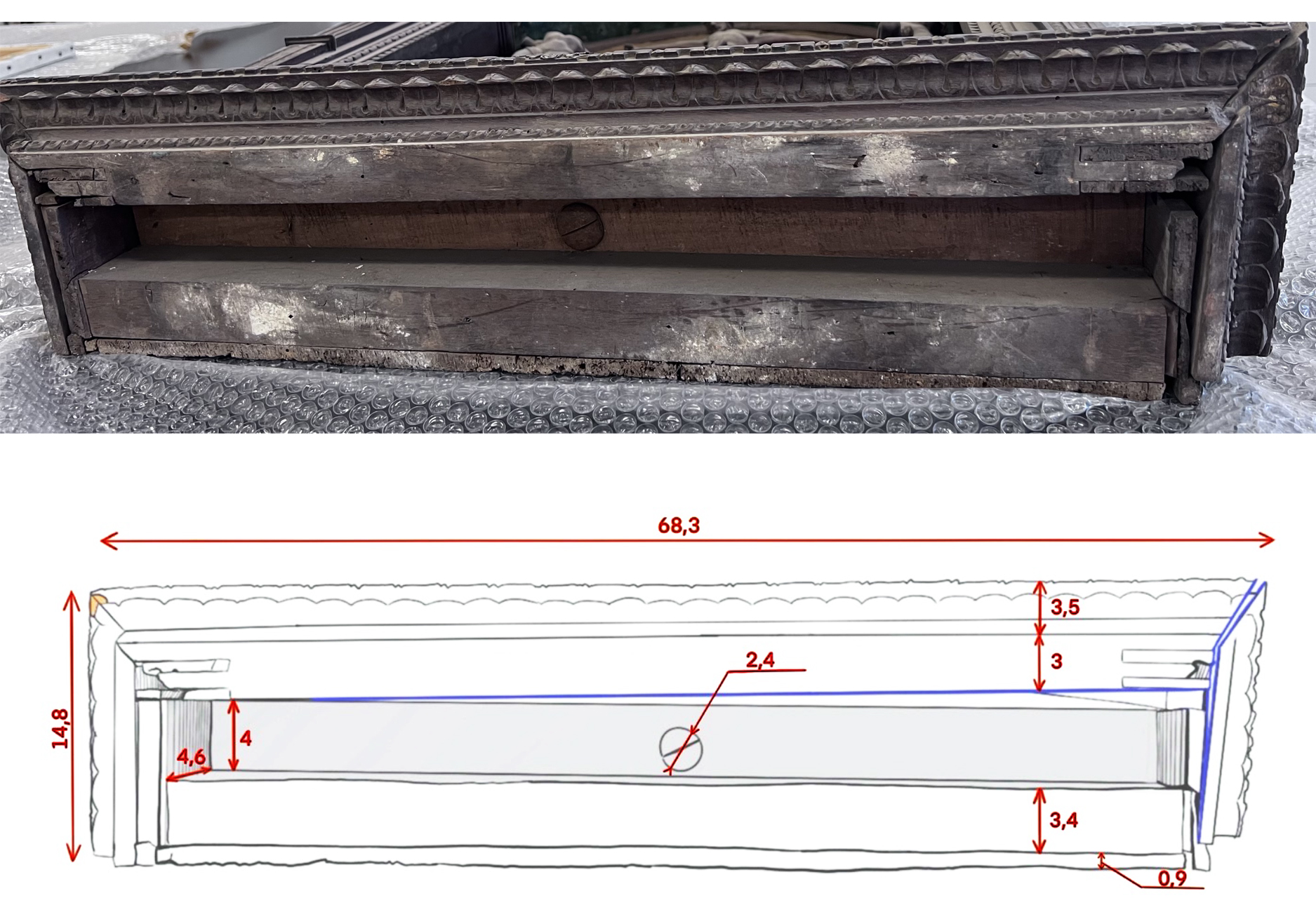

Diagram of the altarpiece with measurements

Detail of ornament defining the pediment; the lion head modillions and caryatides supporting it; the Cross-bearing angel in the spandrel

This frame is richly and imaginatively ornamented. The pediment contains runs of fluting, leaf-&-dart and egg-&-dart, whilst the lateral pilasters are the tapering, fluted supports of terms. They rise from plinths decorated with imbricated scale ornament, and are crowned with secondary elements holding floral paterae and lozenges. The terms are reduced to the heads of caryatides with hanging veils supporting voluted Ionic capitals, with sun discs between the scrolls, standing on acanthus pedestals; the capitals themselves hold lion head modillions, which in their turn support the pediment. The spandrels to right and left of the arch are filled with images of angels, holding the Cross and crown of thorns. The arch is defined by dentil and leaf tip mouldings, and the base by astragal-&-double bead, knulled fluting, and egg-&-dart.

The carving can be dated to around 1600. The velvet-lined niche is made of walnut, whilst the more elaborately executed sculptures are made of boxwood, which was originally much lighter in colour. At the end of the 19th century, the altarpiece was reworked in the historicist style of the time. Original parts were removed; elements were added; the velvet on the backboard was replaced and the frame and figures were evenly darkened.

Despite these interventions, it is a unique testimony to the late Italian Renaissance, and a demonstration of private piety as it had been revitalized in the Counter-Reformation. For much of the 20th century, historicism was held in low esteem and the Calvary was forgotten. It was not until 2021 that it was rediscovered in the depot by Ulrich Becker, and re-identified with the help of external colleagues (Dr Matthias Weniger and Dr Jens Burk, both from the Bavarian National Museum in Munich). Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova from St Petersburg worked on the challenging task of conserving it under the supervision of Paul-Bernhard Eipper, as part of her internship at the Conservation Department at the Universalmuseum Joanneum in Graz.

In view of the renewed appreciation for the 19th century and its historical revivalism, it was imperative to respect the evolution of the work during this period, which ruled out uneven restoration results from the outset. The uniform over-patination was therefore retained, especially as it had been matched to the 19th century red velvet background, which was now a deep ochre (the original 17th century background fabric had been black, as remnants under the nail heads revealed).

Impressions of the missing stars in the blue velvet lining the canopy. Photo: Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova

Some original blue velvet survived in the canopy of the arch; this had been patterned with golden stars, after the starry canopies of some painted altarpieces. The stars, which were now all missing, had only survived through their silhouettes imprinted in the velvet, and replacements would be modelled on these. In the spirit of historicism, a burgundy red velvet was again chosen for the back wall. The altar was returned to the Alte Galerie collection and was given the new inventory number AG Inv.-Nr. P 406.[2]

The state of the altarpiece upon admission to conservation, according to visual observation: there were losses of wood to the left-hand top slope of the pediment, and the lower corner of the right-hand slope; also to the elements holding floral paterae and lozenges above the fluted support of the caryatid on the left-hand side.

The base of the altar

The lower part of the altar consists of four sides with a recessed area in the centre. There are two horizontal elements, 68.3 cm. long; the upper with a height of 3 cm. and the lower, 3.4 cm., and two vertical 14.8 cm. pieces of wood at each side – one of which was missing on the right-hand side. The horizontal and vertical wooden elements were fastened together by means of straight metal nails (possibly a later intervention). The carved mouldings were attached to this carcase with glue and metal pins. Between the two horizontal framing pieces of wood is another, recessed, board, presumably made of boxwood; it has been fitted with a metal mount 2.4 cm. in diameter, to which the rocky Mount Calvary is fixed. A pine backboard 0.9 cm. deep forms the reverse of the altarpiece.

This diagram shows the construction of the base from underneath, with dimensions in centimetres

Visible damage to the base of the frame

The right-hand vertical plank with a carved moulding was detached from the base and held on only by means of the metal mount. The upper plank with a carved moulding was also detached, mainly on the right side. There was general dust contamination, with traces of white spots (presumably whitewash) all over the base; the largest spots were localized on the upper and lower planks.

Damage to the façade of the altarpiece

The frame is almost certainly made of walnut wood, whilst the carved figures in the crucifixion scene are made of boxwood. In the 19th century all the figures had been covered with black water-soluble paint, in order to tone down the light golden colour of the boxwood (this would originally have been as pale as ivory against the 17th century black velvet ground). The surface was then covered with shellac.

The entire surface of the altarpiece had suffered from dust contamination, which had changed its overall colour. There were also traces of woodworm damage all over the surface of the frame; that is, only in the walnut wood – there were no holes on the boxwood figures. The pediment had losses, mentioned above; whilst moveable elements of the crucifixion scene, which had loosened, included the figures of the Virgin and the Magdalene, as well as the wooden scroll on the crucifix inscribed ‘INRI’ (Iesvs Nazarenvs Rex Ivdæorvm).

There were traces of previous conservation in the form of mastic of unknown origin, used to seal holes caused by the woodworm. This filler was tinted to match the colour of the wood.

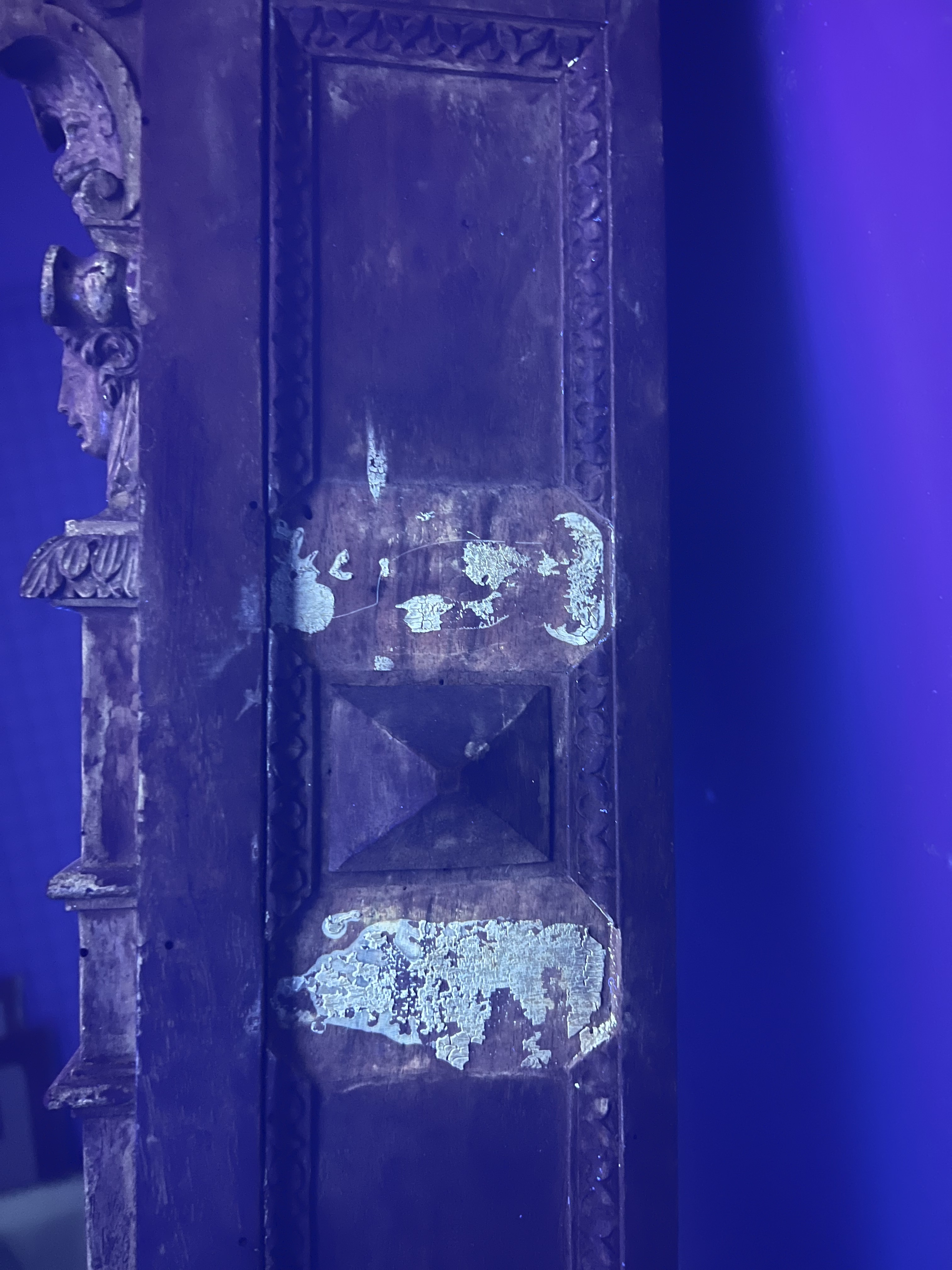

Damage to the sides of the frame

Missing elements on the side of the frame, seen under UV light

Missing elements on the side of the frame, seen under UV light

On the right-hand side is an inscription in white paint, ‘2165’, presumably an old inventory number. Actual damage included general dust contamination; a carved ornament on the right-hand side was detaching from the base, and remnants of old glue were visible where it had been fixed. Three decorative elements had been lost, and there were traces of brown glue in the losses.

Fabric

There were two types of velvet fabric inside the aedicule. The original 17th century greenish-blue fabric which represents the sky was still in situ in the canopy; it was presumably completely blue originally, but had yellowed over time. There were numerous losses in the fabric, which is a straight plain weave and which retained traces of the eight-pointed stars imprinted on its surface. There was a 0.3 cm diameter hole in the middle of each star imprint, where the metal star was attached to the wood behind the ‘sky’.

Behind the figural group of the crucifixion was a late 19th century yellow ochre fabric. The fabric had been cut, and glued onto the wooden backing; it had come away from the base in places, and was crumpled; there were tears in the upper part. The edges were cut unevenly and were frayed. General dust contamination had helped to change the overall colours of both fabrics.

General conservation of the altarpiece

The altarpiece before conservation, photographed by ultraviolet light, with a light sandy-orange colour visible, indicating that the surface is covered with an irregular and uneven layer of shellac, applied later. Photo: Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova

After photography of the altarpiece, and before starting work, all the moveable elements of the altarpiece were taken out, in order to preserve them.

Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova working on the altarpiece

Dusting was carried out in several stages, using a dry synthetic brush and a vacuum cleaner; and then conservation sponges (‘Akapad’ soft clean pads) for dry cleaning, as well a microporous PVF-sponge (‘Blitz-Fix’),[3] slightly moistened with water. Dirt was removed from hard-to-reach elements with a cotton swab slightly moistened in water and small brushes [4].

The figure of God the Father, halfway through cleaning

After dusting, the altarpiece regained the richer, brighter colours characteristic of boxwood and walnut.

Dusting the ochre velvet around the figure of Christ

Dusting of the ochre velvet was carried out using a synthetic brush and a vacuum cleaner, and dusting of the greenish-blue fabric was done with a soft dry brush. After cleaning the fabrics also regained a much brighter colour.

Restoration of the frame

Silhouettes of missing elements on the right-hand side of the frame. Photo: Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova

The remnants of old glue (presumably rabbitskin or bone glue) were removed from where the lost wooden elements had been previously fastened. An aqueous solution of methyl cellulose, with an exposure time of 5-7 minutes, was brushed onto the area, and – after the glue swelled and softened – it was removed with a spatula.

To make good the loss of the wooden elements on the right side of the altarpiece, a mould was taken from a similar area on the other side of the frame, using a two-component silicone compound (‘Alpa-Megaplast A’ and ‘Alpa-Megaplast B’). After ten minutes the mould had set and was ready for use.

It was filled with another two-component composition (Gößl & Pfaff ‘GP SV 427 -1’ and ‘GP SV 427 -2’ (1:1)), and after 24 hours the form was removed from the silicone mould, and finished using a scalpel and sandpaper [5]. The modelling of the form took place directly under the area of loss, and minor voids and inconsistencies were supplemented layer by layer with the same composition. Each layer dried for 24 hours and was remodelled until the fragment fitted tightly to the base, filling the loss without either voids or excess paste. Two similar infills were produced by the same process.

Replacing the missing wooden elements

On the lower right-hand side of the frame, where two wooden elements were missing, it was necessary to reconstruct them to complete the overall structure of the altarpiece; they were made from wood, and reduced to the size of the lost pieces by sandpapering.

The figures and background of the crucifixion scene

The Calvary abstracted from its frame, minus the removeable figures of the Virgin and Magdalene. Photo: Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova

In the centre of the altarpiece base, the metal mount holding the carved wooden Mount Calvary and crucifixion scene was unscrewed, with the help of a pair of metal tongs. The figural scene was then removed from its niche (it was taken to the conservation table for further work), which also allowed the background of ochre-coloured fabric to be fully revealed.

The altarpiece frame without the Calvary; the 19th century velvet ground revealed. Photo: Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova

The areas which had been hidden from the light could now be seen to retain quite an intense shade of red; the initial colour of this 19th century velvet might have been chosen to represent the liturgical purple of Holy Week, or to symbolize the blood shed by Christ.

In the task of reconstructing the original state of frame and figures, the evidence of this red velvet had to be taken into account, since it had been chosen to harmonize with the colour-washed wooden figures and produce an overall integrated effect. The restoration work carried out in 2023 was therefore weighted to respect the appearance of the altarpiece as it was in the late 19th century, rather than aiming for its appearance at the beginning of the 17th century.

Bases of the sculptures of the Virgin and the Magdalene; the shaped hollows to hold them in the top of the carved Mount Calvary, looking down from above

After dismantling the scene of the crucifixion, two of the figures were found to be moveable: those of Mary Magdalene and the Virgin, which no longer fitted the hollows made for them on Mount Calvary, because the ancient glue had lost its properties. It clung round the bases of the figures, and clogged the hollows in lumps and clots. The removal of this dried glue was carried out according to the method previously devised, and described above.

The painting conservation council of the Universalmuseum Joanneum museum made the decision that the ochre-coloured velvet should after all be stripped off, since it wasn’t original, it did not fit right down to the wooden base, and it suffered from worn areas and frayed edges. It was removed using a metal spatula. The wooden base under the fabric was rendered free of dust according to the procedure above; and in the process of this dusting, threads from a black material measuring 0.1-0.2 cms long were found. This fabric was presumably the original background from the 17th century, lodged inside the wooden arch of the frame; it was visually close in composition to the original blue fabric from the canopy of stars.

Reconstruction of the stars

Silhouettes of stars on original 17th century blue velvet from canopy

With the help of a transparent Melinex film and a liner, the outline of the eight-pointed star was transferred from the impressions made in the fabric. Using this, silicon moulds of the star were created, using a two-component composition (Gößl & Pfaff ‘GP SV 427 -1’ and ‘GP SV 427 -2’ (1:1)). All the work was carried out according to the methodology described above, relative to the replacement of lost elements of wood.

Moulds and cast stars

Forty-two stars were cast from the moulds. Each one was then painted with Schmincke brown gouache, and lacquered with shellac diluted in ethyl alcohol. A hole with a diameter of 0.3 cm. was made with a screwdriver in the centre of each one.

A small, 2-4 cm. wooden stick was inserted into each hole, and held there with fish glue (Kremer Fischieim Flüssig), at the junction of the hole and the wooden stick. Great care was taken to ensure that the adhesive did not touch the fabric.

Further research into the significance of the eight-pointed star made it possible to supplement the historical reference. The stars in the sky are symbolically identical to those on the veil or maforium of the Madonna – the Queen of Heaven and Mother of God; the Byzantine icon of the Burning Bush (seen as a prefiguration of the Virgin) represents the Bush as an eight-pointed star, whilst the Virgin herself is shown wrapped in a veil of fire. An eight-pointed star is formed of two swallow-tailed crosses laid one on top of the other, and is also used to depict the Star of Bethlehem.

Fixing together the elements of the altarpiece

The ancient remains of glue having been cleaned from the figures and their setting, all the moveable elements were re-attached using the same Kremer fish glue. It was applied with a brush, after which the pieces in question were fixed with clamps, and left for twenty-four hours. The figures of the Virgin and Mary Magdalene were fitted back into their hollows in the rocky base and glued there, without the need for clamps. Small fragments – the fingers of St John the Evangelist, the scroll inscribed ‘INRI’ – and new replacements were also glued in place.

The replacement stars, mounted on the original velvet of the canopy. Photo: Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova

The newly manufactured stars on their short stems were inserted into the existing holes in the wooden canopy, the stick of each one passing through the original hole on the blue fabric. With the help of a thin brush and more fish glue, the sticks were additionally fixed at the junction of their bases with the wood of the canopy.

Toning and fitting the new velvet

The same meeting of the painting conservation council of the Universalmuseum Joanneum museum which had decided to remove the ochre-coloured velvet from the background board also decided to replace it with a deep burgundy velvet. The new background was cut from a piece of 100% cotton velvet fabric with a margin of 0.5-1 cm at the edges, and was glued to the wooden base with an aqueous solution of Methyl cellulose applied with a brush. The edges of the fabric were tucked under the wooden plinth. The fabric had previously been coated with an ochre coloured acrylic ink (Schmincke Aero Colour), using an airbrush. This coating layer eliminated any shine on the new fabric.

Partial retouching of the altarpiece

Losses on the Mount touched in

Traces of previous conservation had been revealed on the carved Mount Calvary at the base, after surface dust removal: the brown-painted plaster used to fill the woodworm holes had changed colour over time, or had been lost or worn away. These losses and scuffs were freshly touched in with Schmincke watercolour paints.

Additional surface coatings were waived. It was felt that the surface lustre achieved by simple cleaning was sufficient, and above all authentic. The altarpiece is displayed today according to its interpretation and restoration around the year 1900. All measures taken in 2023 are reversible, and allow for a future reconstruction of the original late Renaissance appearance.

Altarpiece of the crucifixion, c.1600 with 19th century additions; boxwood, walnut; canopy lined with original and backboard lined with modern velvet; after conservation by Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova, 2022. Photo: Nicolas Lackner/UMJ

*******************************************

Acknowledgements

During the work carried out on the property, we received friendly support from our colleagues Brigitte Puchleitner-Knödl BA, Mag. Art; Mariia Bakhareva, Mag. Art; Barbara Molnár-Lang and Dipl.-Rest. Evgeniia Sannikova for which we would like to express our sincere thanks.

Literature

P-B. Eipper, ‘Historische und zeitgenössische Substanzen, Materialien und Methoden zur Reinigung von Gemäldeoberflächen’, in Handbuch der Oberflächenreinigung, ed. P-B. Eipper, 7th edition, 2021, vol. I, pp. 91–128

P-B. Eipper, ‘Skulpturenrestaurierung’, in Konservierung, Restaurierung und präventive Maßnahmen, Lehrbuchverlag, London 2024, pp. 267–451

Geissmann, ‘Polyvinylformal (PVF)-Reinigungsschwämme (bisher bekannt als „PVA-Schwämme”): lösliche Bestandteile und Verwendung in der Konservierung-Restaurierung’, in P-B. Eipper (ed.), Handbuch der Oberflächenreinigung, 7th edition, Munich 2021, p. 497

D. Ivanova, P-B. Eipper, U. Becker, ‘Rediscovery and restoration of a

late Renaissance family altarpiece, altered in the era of Historicism’, in ExpoTime!, double issue Dec.23 / Feb. 2023, Verlag Dr. Müller-Straten, München 2023, pp. 68–73

Johann Georg Sulzer, Allgemeine Theorie der Schönen Künste. Bd. 1. Leipzig, 1771; Verlag/Drucker: Weidmann; Reich

Universalmuseum Joanneum, Jahresbericht 2022, pp. 350-52

*******************************************

Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova & Paul-Bernhard Eipper

Authors

Ass. Prof. Dr Rer. Medic. Dipl.-Rest. (FH) Paul-Bernhard Eipper

Leiter Restaurierung

Email address: paul-bernhard.eipper@museum-joanneum.at

Phone no: +43-699/1330-8811 Mobile: +43-664/8017-9561

Universalmuseum Joanneum

Museumsservice Weinzöttlstraße 16, 8045 Graz, Austria

Valeriia Dmitrievna Ivanova, Restorer and artist

Lecturer at the Academy of Restoration and Design

Trainee assistant at the Ilya Repin Academy of Fine Arts

Member of the Union of Artists of St Petersburg

Phone no: +79218718791

Email address: spbrestauro@gmail.com

Dr Phil. Ulrich Becker

Kulturhistorische Sammlung – Museum für Geschichte

Sammlungskurator / Curator of Collections

Email address: ulrich.becker@museum-joanneum.at

Phone no: +43-664-8017-9771

Universalmuseum Joanneum

Abteilung Kulturgeschichte Sackstraße 16, 8010 Graz

*******************************************

Footnotes

[1] Ivanova, Eipper, Becker, 2023, pp. 68–73; Eipper 2024, pp. 397-411

[2] Universalmuseum Joanneum, Jahresbericht 2022, pp. 350-52

[3] Geissmann, M., ‘Polyvinylformal (PVF)-Reinigungsschwämme (bisher bekannt als ‘PVA-Schwämme’): lösliche Bestandteile und Verwendung in der Konservierung-Restaurierung’, in Eipper, P.-B. (ed.), Handbuch der Oberflächenreinigung. 7. ed., Munich 2021, p. 497

[4] Eipper, P.-B., ‘Historische und zeitgenössische Substanzen, Materialien und Methoden zur Reinigung von Gemäldeoberflächen’, in Handbuch der Oberflächenreinigung. 7. Auflage, 2021, Bd. I, S. 91–128

[5] Universalmuseum Joanneum, Jahresbericht 2022, p. 349