Book review: Hardwick Hall: A great old castle of romance

David Adshead & David A.H.B. Taylor, eds, Hardwick Hall: A great old castle of romance, published by Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre & the National Trust, 2016, pp. 402, 320 colour & 20 b-&-w ill.; IBSN 9780300218909; £75.00

This is a companion volume to the major study of Ham House published in 2013, and with luck the second of a collection of such books on great British country houses, their history and collections. Like its forerunner, it is a huge and comprehensive work, containing twenty full chapters and seven appendices contributed by twenty scholars; it is similarly beautifully produced and illustrated, and covers every aspect of the house and all it contains. It has, besides, a great deal on the remarkable woman – Bess of Hardwick (c.1521/22-1608) – who built the house, and on the various Dukes of Devonshire who have contributed to its survival, and to its organic growth and change.

British School, Elizabeth Hardwick (‘Bess of Hardwick’), Countess of Shrewsbury (1520-1608), c.1580, o/c, 24 1/2 x 21 1/2 ins (62.2 x 54.6 cm.), Hardwick Hall, NT 1129212

The estate of Hardwick belonged to Bess’s family, and was bought by her after the death of her brother. In 1587, when she was about 65 and on her fourth, least sympathetic husband (George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury), she began to build the Old Hall at Hardwick (now an empty shell), and in 1590 the New Hall. This appears from the outside like a secular version of the Sainte Chapelle in Paris – a palace of great glass windows set in pale amber stone. It was designed and built by Robert Smythson, who had previously built Wollaton and co-constructed Longleat. Unlike Ham House, it has no ceremonial great doorcase in the form of an altarpiece; the outside is all calm grandeur, ornament and symbolism being left to riot on the inside.

William Gryffyn, stone screen in the Great Hall, 1597. Photo credit: ©National Trust Images/ Andreas von Einsiedel

Here, in the interior, however, Hardwick is filled – like Ham House, although in a different degree – with frames of every kind: architectural, stone and plaster; tapestry borders, the edges and façades of furniture, and the actual picture frames. Immediately upon entering, in fact, the screen across the hall (which supports a gallery) provides the classicizing reference of an extended aedicule which the outside lacks. This anticipates the presence of borders and framed openings throughout the house, and, in the realm of the book, points to surviving information on many of the artists and craftsmen who constructed them. So, whilst the image of the carved stone screen above opens the second chapter on the internal arrangement of the house, it also introduces us to Appendix 1, ‘The Hardwick Archive’, a summary of the documents relating to the house and family, now mostly kept with the archive of the Devonshire Collection at Chatsworth House [1]. These contain, amongst many other things, the building accounts of the New Hall, including the name of William Gryffyn, the carver of the hall screen, and the payment he received – £6 [2].

Hans Vredeman de Vries, details of capital & enatblature, Den eersten boeck, 1565, Antwerp. Photo: Deutsche Fotothek, Saxon State Library/ State & University Library, Dresden

The classicism of the screen is splendidly geometrical and Elizabethan, with Roman Doric columns, strongly marked mazelike decoration on the pedestals, and emphatic triglyphs and metopes on the frieze of the entablature; its source has been traced to a design by the Netherlandish artist and architect, Hans Vredeman de Vries [3].

Gryffyn also carved a chimneypiece in Bess’s original Withdrawing Room, although this was later destroyed when the room was adapted in the 18th century [4]:

‘The chimney piece vast, stuck with spar: & the figure of Abraham going to sacrifice Isaac the stucco tremendous as big as life.’ [5]

Chimneypieces generally are a striking feature of Hardwick, articulated in the same classical and geometrical vocabulary as the hall screen, and providing an interesting sidelight on the severe simplicity of Elizabethan picture frames.

Thomas Accres, chimneypiece & wall panels, Green Velvet Room (the Best Bedchamber)

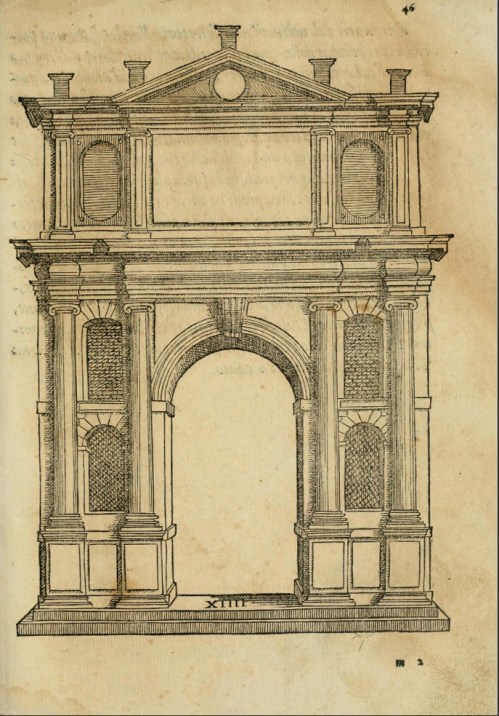

Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554), Libro estraordinario…, 1566, plate XIII

The example by Thomas Accres in the Best Bedchamber (Green Velvet Room) with its associated obelisk-bearing doorcase, stone and wood panelling is a splendid example, and seems to bear at least a structural debt to Sebastiano Serlio (for instance, his book of thirty patterns for door- and gate- ways [6]), as well as to Netherlandish prints; see also the work of Anglo-Flemish tomb-makers (below). The authors consider the question of design amongst the hierarchy of architect (Robert Smythson), supervisor (John Balechouse, otherwise Jehan Baleschoux or John the Painter), and stone carvers (William Gryffyn, Thomas Accres and Abraham Smith): this is a constant and fascinating problem with regard to many types of interior and architectural carving, including picture frames. Every situation is of course different: in the 18th century William Kent and Robert Adam kept a rigorous control over the execution of their own designs by the craftsmen they employed, but responsibility may have been much more fluid during the 16th century, especially when the historical equality of, for instance, carvers and artists in the early Renaissance is considered. When patternbooks were available – by Serlio or by Netherlandish designers – either through Bess of Hardwick or Smythson, the craftsmen’s own ability to replicate or create variants on those designs would have been equally possible as having set patterns issued to them.

William Bramley, painted panelling in Queen Mary’s Room (the Inner Chamber to the Best Bedchamber)

The stone mouldings of chimneypieces and doorcases throughout the house have been recorded and drawn as twelve individual profiles, which are illustrated in Appendix 3, provoking similar queries as to the identity of the designer(s), while

‘comparable questions are raised by the woodwork. William Bramley’s panelled dados…on the second floor…[have] strong but simple geometrical patterns and [are] painted in faux marquetry’ [7].

The dado in Queen Mary’s Room, for example, has a pattern of outline strapwork frames at the bottom, and a Mannerist cartouche above between two horizontal and ornamental panels. William Bramley may quite easily have been responsible himself for adapting these designs.

Strapwork overmantel, the Low Great Chamber

The overmantel in the Low Great Chamber, the dining-room of the house, echoes these geometric strapwork designs in stone, converting them to a broad frame-like border for the central scrolling cartouche and plaque with its gilded exhortation. Just like the chimneypiece in the Green Velvet Room and the hall screen, this strapwork border and cartouche derive from contemporary pattern books and engravings; in this case from Jacob Floris’s Compertementorum quod vocant multiplex genus.

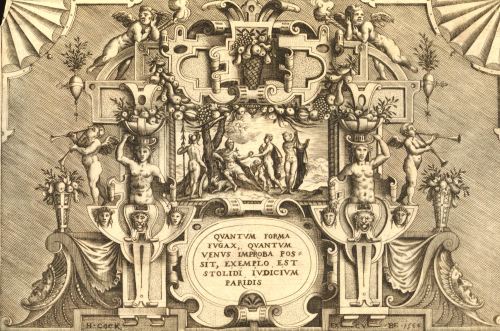

Jacob Floris (after; 1524-81), cartouche from Compertementorum quod vocant multiplex genus…, Pieter van der Heyden, 1566, Antwerp, ©Victoria and Albert Museum

Anthony Wells-Cole, in Chapter 3 of Hardwick Hall…, examines the part played by the increasing wave of print-making during the 16th century, in which subject illustrations – religious, mythological and symbolic – as well as architectural and ornamental designs, became available in ever greater numbers, diffusing fashions in decorative art very quickly across national boundaries. Bess collected a wide range of these prints, and seems to have used them as models for her needlework, as well supplying inspiration for the craftsmen she employed in her house:

‘In embracing up-to-date continental images, and using them to decorate and furnish great houses – houses which nevertheless remained quintessentially English – Bess was an archetypal Renaissance prince, all the more remarkable at the time for being a woman.’ [8]

Overmantel with strapwork cartouche, based on a print after Jacob Floris (below), in Bess’s bedchamber (‘my Ladies Bed Chamber’)

Jacob Floris (after; 1524-81), cartouche from Compertimentorum quod vocant multiplex genus …, Pieter van der Heyden, 1566, Antwerp, ©Victoria and Albert Museum

The prints she favoured were in the main Netherlandish; these were both fashionable, and readily available, and they were admirably suited as vehicles for her emblematic and allegorical approach to interior decoration. Such prints were generally to have a marked influence on carved picture frames from the 17th century onwards, although at the time when Bess was decorating both the newly-built Hardwick Halls they were instead employed for architectural features such as overmantels, picture frames still being relatively plain and simple objects. Ornate borders tended to be found, not around paintings, but edging tapestries, where they mimicked (ironically) the architectural mouldings and decorative friezes of the 16th century Renaissance wooden cassetta.

The Ulysses tapestries, c.1550-65, Brussels, in the High Great Chamber

There are two chapters in the book, both by Helen Wyld, on Hardwick’s impressive collection of tapestries: one on those assembled by Bess, and one on the 17th century tapestries. The most splendid of the earlier hangings still at Hardwick are the set telling the story of Ulysses, made around the mid-16th century in Brussels, and bought for the most important of the state apartments – the High Great Chamber, where they remain.

‘The entire decorative scheme of the High Great Chamber is structured around these hangings: the fixed panelling and plaster below and above them are tailored to the height of the set, which exactly fills the width of the walls… the width of the chimneypiece was calculated to achieve this effect.’ [9]

Niclaes Hellinck (fl.1559-76), after Michiel I Coxie, The homecoming of Ulysses, c.1550-65, Brussels, tapestry, 364 x 500 cm., NT 1129448.8

The care taken to accommodate the dimensions of the architectural fittings to this set of tapestries is an index of their contemporary value: tapestries were functional, at a time when it was important to conserve heat in a winter room; they were beautiful, ornamental and richly coloured in contrast to whitewashed plaster walls or wooden panelling; their comparative richness and/or rarity were markers of wealth and status; and they might convey moral or exemplary meanings. It is interesting, if slightly disconcerting, to see how rarely the borders of such tapestries are ever mentioned when the pictorial elements are under consideration.

South Netherlandish, The Devonshire hunting tapestries, 1425-30, largest dimensions 385.4 x 1023 cm., ©Victoria and Albert Museum

The very earliest group of hangings once at Hardwick and now in the V & A are the Devonshire hunting tapestries, made in the southern Netherlands in the 1430s. They are a disparate group of extremely large pieces (varying from 3.8 to over 4 metres high), which have been cut about and used in different ways through the years, but have never had either integral borders or (presumably) separately woven attached borders. They are vibrant, animated, beautifully drawn and composed, and yet they look unfinished. They were almost certainly hung in the entrance hall at Hardwick, a double-height room where they would have occupied the upper register above the panelled walls; here they would have been framed by the cornices at the top of the panelling and the walls respectively.

Niclaes Hellinck (fl.1559-76), after Michiel I Coxie, Ulysses taking leave of his family, c.1550-65, Brussels, tapestry, 364 x 500 cm., & detail, NT 1129448.3

Separated from the place where they hung for around 250 years, they have lost not only their physical but their focal setting; in comparison with the Ulysses tapestries, which are set back within their integral ‘frames’ and isolated from other elements of the High Great Chamber, the ‘Devonshire Hunts‘ appear diminished and incomplete. In the detail from the Ulysses tapestry (above) it can be seen that the corner cartouches which might have decorated the corners of a wooden frame have been replaced by the goddesses relevant to the myth, while the figure of Homer is at the bottom centre, and an explanatory Latin inscription is set into the top ‘rail’. This inscription has a faux architectural moulding, and the whole frame is bordered by ‘top’ and ‘sight’ mouldings of an enriched ribbon guilloche. This part of the tapestry is therefore necessary to the pictorial element in the same way as a wooden frame to a painting: it comments on what is happening in the scene, indicates the source, provides a glimpse of another world which intersects with the human world of the hero, and also gives that vital transitional area between representation and reality.

The Great Hall, Hardwick, with 3 of the 8 Scenes from country life tapestries after Jordaens visible

The 17th century tapestries at Hardwick are discussed in chapter 13, where we learn that (Hardwick being hung throughout with tapestries by 1601, when an inventory was taken) the later pieces have come from other family houses, including Chatsworth. They include a set of eight after Jordaens which hang around the upper register of the entrance or Great Hall where the Devonshire hunting tapestries used to hang during Bess’s life. Grand in scale and set within integral architectural ‘frames’, these provoke the first mention of a tapestry border:

‘…the Country life series marks a new direction in Flemish tapestry design, one characterized by monumental figures, shallow fictive space and the abandonment of division between border and main field.’ [10]

Jacob II Geubels after Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678), The huntsman & his hounds, from Scenes of country life, c.1630-35, tapestry, 375 x 505 cm., NT 1129596.6

They are beautifully designed and beautifully made; a series of huge Baroque Flemish aedicular portals looking onto landscapes and gardens where hunters and lovers cavort, or into kitchens full of game, into poultry runs, and into niches of musicians. They ‘are especially important as they are probably the earliest weaving of the designs’, which cost ‘ffower hundred and twelve pound i s[hilling]’ in 1636 [11]. Hung as they are, around the Great Hall, they form a vast decorative colonade on either side, the columns parcel-gilt and adorned with têtes espagnolettes, trophies or swags of fruit, the entablatures crawling with half-alive, half-sculptural putti and cherubs, the arches pierced or imprisoning satyrs in their spandrels. The frames are now so much one with the pictorial scenes that they can no longer be ignored; like a fanatsy by William Beckford they have overwhelmed the human content in a great architectural capriccio.

A set of Mortlake tapestries was also acquired, possibly by William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire and great-grandson of Bess (1617-84), or by his mother, Christian Cavendish [12]. The designer at the Mortlake Manufactory was the German Francis Clein, Charles I having failed to lure Van Dyck into the post; Clein also designed furniture and executed much of the painted decoration at Ham House. The Hero and Leander series acquired by the Devonshires is striking, animated and politically significant, but an even more interesting Mortlake acquisiton is the single small work installed in the 19th century on the ceiling of the chapel.

Francis Clein (1582-1658) after Titian, The supper at Emmaus, c.1630-40, tapestry, 350 x 250 cm., Mortlake Manufactory, NT 1129560

This is one of possibly three tapestries designed at Mortlake which have fictive frames – that is, integral reproductions in silk and wool of trompe l’oeil giltwood frames which contain the central pictures as though they were, in fact, paintings. The others are a portrait of Sir Francis Crane, who directed Mortlake, and a replica of Van Dyck’s Self-portrait with Endymion Porter – the latter is not credited to Mortlake, but was almost certainly produced there. They are extremely unusual; the Supper at Emmaus after Titian especially so, in that another surviving version of this piece – at St George’s Chapel, Windsor (1660s), and apparently as also with the few others produced [13] – has a more fantastic aedicular frame similar to those on the Jordaens tapestries, combining swags of realistic fruit, parcel-gilding and ‘live’-looking angels with a greyish, stone-like finish. It is the realism of the Hardwick ‘Titian’ in its fictive ‘giltwood frame’ – with engraved ornament on the cushion frieze, cherubs’ heads and scrolling foliated brackets – which is so rare, unexpected and stunning.

As well as tapestries, the house is noted for its collection of embroidered and needlework pieces associated with Bess of Hardwick; these are the subject of chapter 7, by Emma Slocombe. They include ecclesiastical vestments, acquired by Bess’s second husband, Sir William Cavendish, through work connected with the Reformation, and re-used for domestic furnishings. Hangings and covers in the Chapel, for instance, were created from 15th century orphreys – the wide embroidered bands sewn onto chasubles. [14] The collection also includes the very different pieces worked by Mary, Queen of Scots, when she was imprisoned in the hunting lodge owned by Bess’s last husband, the Earl of Shrewsbury, and later in Sheffield Castle; these far from holy pieces were in some cases embroidered with seditious inscriptions and symbols.

The judgement of Paris, 1574, needlework table carpet, 46 x 60 ins (117 x 154 cm.)

Amongst the more innocent domestic pieces is a table carpet sewn in silk on canvas, bordered with a wide margin of undulating and fruiting vines, with armorial bearings and heraldic animals. Inside this is another type of fictive frame holding a scene with the judgement of Paris. It is in the form of a very Mannerist leatherwork frame, with scrolls clasped around an oval egg-&-dart moulding; its realism is enhanced by shadows between the scrolls and the moulding, and by the thickness of the ‘leather’ being shown, as well as by the colouring.

Jacob Floris (after; 1524-81), cartouche from Compertimentorum quod vocant multiplex genus …, Pieter van der Heyden, 1566, Antwerp, ©Trustees of the British Museum

The pictorial scene (and to some extent the scrolling framework) has been traced to another print after Jacob Floris; however, the scrolling cartouches in these prints, although based originally on the curling edges of an animal hide, have hardened in their passage through the stuccowork of the Château de Fontainebleau (1536-1540s), the stucco ceilings of Alessandro Vittoria in Venice and Vicenza (1550s), and the engravings of the 1540s and 1550s which diffused these designs. The professional embroiderer responsible for the carpet may have lifted the scene of Paris and his three goddesses from the Floris print, but her scrolling framework is imaginatively different in composition and feeling from the rigidly sculptural cartouches in the print, and looks forward to the more organic ornament of the Auricular style in the next century.

Wall hanging, Lucretia with Chasteti and Liberaliter, embroidered appliqué, 110 x 114 1/2 ins (278 x 339 cm.), NT 1129593.2

Another significant embroidered work is the set of five pieces known as the Noble women of the ancient world. These are actually large hangings, nine feet high, which were commissioned by Bess for the state apartments at Chatsworth. The description of these is fascinating, including an assessment of the stages of group work involved in their making, an inventorial entry, and a connection made between the embroidered frameworks and the production for Elizabeth I of painted interiors with trompe l’oeil Renaissance architecture [15]. The Lucretia hanging also has evidence of the involvement of Mary, Queen of Scots, the figure of Lucretia echoing the pose of Lucretia in a painting belonging to Mary; whilst Chastity, on the left, may be a white-clad portrait of the Scottish queen [16].

Sketch of the Swan Theatre, London, after a drawing by Johannes de Witt (1566-1622 ), p.247 (folio 132 recto), in Arnoldus Buchelius, Adversaria, MS, 1592-1621, London; Universiteitsbibliotheek, Utrecht, Hs 842 (Hs 7 E 3)

The frameworks holding the figures are, in their structure and presentation, irresistibly evocative of an Elizabethan theatre, with figures emerging from arched openings at the back onto a raised stage, between classical columns set on large pedestals. This might, since the dissolution of the monasteries and consequent iconoclasm, be the nearest that a woman who had no experience of travelling in Catholic countries might come, late in Elizabeth’s reign, to an everyday knowledge of what is otherwise essentially an altarpiece frame. The reference to Bess’s painters having possibly worked for the queen, producing trompe l’oeil architectural interiors, is perhaps a step further off than what was a common activity for all classes in Tudor London – visiting the theatre.

It is, of course, equally possible that a print of some sort inspired the Renaissance aedicules holding the Noble Women; however, most of the architectural, frame- and cartouche- like forms which were the patterns for chimneypieces and overmantels, embroideries and furniture at Hardwick are Mannerist rather than Renaissance; fashionable, rather than antique; and – save for the odd influence from Serlio, for example – mainly Netherlandish. Some of the furniture, the most notable of the 16th centuries pieces, derives from French sources, and was probably made in France; there was a lot of Netherlandish influence here, as well.

The ‘sea dog’ table, c.1570, probably Paris, inlaid walnut, parcel-gilt & painted, 33 1/2 x 57 7/8 x 33 1/2 ins (85 x 147 x 85 cm.), NT 1127744

The outstanding pieces of furniture include the ‘sea dog’ table, the ‘Du Cerceau’ cabinet, and the Eglantine table, all made around 1570, the first two probably in Paris and prodigally Mannerist in style; the last in London, and more subtly so. This chapter (‘Furniture at Hardwick Hall – I’), by Simon Swynfen Jervis (author of the indispensable Dictionary of design & designers), is a model of packing: descriptions of the pieces, their construction and alterations through time; the history of opinions of them; the influences on them, and prints which inspired them (in the case of the first two); the circumstances of their purchase; the various craftsmen and maîtres who might have been involved in their manufacture; and the possible areas from which they might have come: all these are organized into relatively few pages in concentrated strata of information and suggestion.

‘Du Cerceau’ cabinet, c.1570, probably Paris, oak, walnut, pietre dure, leather, parcel-gilt, silvered & painted, 93 1/2 x 55 x 19 ins ( 237.5 x 139.8 x 48.2 cm.) NT 1127743

Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (1510-84) and Huges Sambin (1520-1601) are the main influences cited for the ‘sea dog’ table and the ‘Du Cerceau’ cabinet, along with a touch of Fontainebleau [17]. There may also be some Italian Mannerist influence at work, and this time from picture frames into furniture, rather than the other way round. The swags of fruit and foliage centred on masks, the bosomy winged caryatides, the parcel-gilt walnut, fluting, broken and open pediments, dentils and guttae, can all be found on ‘Sansovino’ frames from the 1550s; and since the queens of Henri II and Henri IV were both Medici, there was a channel for these elements to enter France. The Hardwick furniture is both madder and more secular than the ‘Sansovino’ frame, however; the prints by Du Cerceau to which motifs from both the cabinet and the table have been traced are so fantastic and grotesque that their recreation in wood is as surprising as with some of the more flamboyant of Rococo designs .

The Eglantine Table, c.1568, probably London, walnut, fruitwood, limewood, pine, ash, wood inlays, 119 1/2 x 50 3/4 ins (302 x 129 cm.), NT 1127774

The Eglantine Table, in contrast, is very spare in its structure; it is basically a plain refectory table with turned and tapered legs (its most Mannerist part), and inlaid classicizing motifs on its base in the style which would thirty years later articulate the Great Hall screen. Its top is its glory: it is formed of three planks joined side-by-side, the central one a single piece of walnut, the others made of five and seven pieces respectively of fruit- and lime- wood, and all of them a riot of trompe l’oeil and strapwork marquetry (the latter again deriving from Jacob Floris’s Compertementorum quod vocant multiplex genus…, published a couple of years or so before the table was made) [18]. The heraldic symbolism, musical instruments and pieces of music have all been ferreted out, and the possibilities of its manufacture are discussed; it is also compared with the ‘Brome Table‘ in The Burrell Collection, which supports the idea of a London source.

The book is much more than a collection of essays on each category of objects it contains. The opening chapters, on the history, building and internal organization of the two Halls, Old and New, and of their creator and the various strands of her family, echo through all the subsequent pieces, and throw up other chapters set at a slight angle to a straightforward catalogue: not ‘Paintings at Hardwick’ but ‘A Derbyshire portrait gallery: Bess of Hardwick’s picture collection’; ‘The household at Hardwick in the 17th century’ (which uses the archives, and more specifically the quantities of account books, to resurrect the number of staff, how everyone was fed, where clothes were bought, and what social activities took place); and a piece on the almshouses Bess endowed and her tomb, which is enlivened by details of her death, funeral and wake.

Tomb of Bess of Hardwick, the Countess of Shrewsbury, in Derby Cathedral

Thomas Accres, chimneypiece & wall panels, Green Velvet Room (the Best Bedchamber)

Her tomb, which is attributed to the architect of Hardwick, Robert Smythson (or his son, John), after tombs made by the Southwark school of ‘Anglo-Netherlandish tomb-makers’[19], is remarkable for the vocabulary it also shares with architectural fittings at Hardwick – notably some of the chimneypieces, and the doorcase of the Best Bedchamber, binding Bess’s last home, as it were, to her domestic one. It, like the latter, shares elements (even more, of course, given its setting) with architectural stone altarpieces.

The 16th century cassetta in use at Hardwick; some examples from before the 1601 inventory, in the Long Gallery

The conventional picture frames at Hardwick, in the main perhaps less immediately striking than (although as historically interesting as) those at Ham House, are examined in an appendix by Christopher Rowell [20]. Some of the portraits surviving from the eighty pictures recorded in the 1601 Hardwick inventory have original frames; some are later or modern replicas, but they are all variations on the ebonized and/or parcel-gilt Renaissance cassetta (or cabinetmaker’s frame, the Northern equivalent).

Hans Holbein the younger (after; 1497/98-1543), William Fitzwilliam, 1st Earl of Southampton (mislabelled Thomas Moore), 1510-42, o/panel, 33 x 24.5 cm., NT 1129168

Christopher Rowell singles out the frame on the Earl of Southampton as an example of ebonizing (painting or staining black) over fruitwood, the warm browns of the latter now showing through the worn finish, especially on the frieze of the bottom rail. Groups of such portraits would have presented an important affirmation of family and status; they seem to have been hung in the window embrasures of the rooms where they were displayed in Bess’s lifetime (as above), rather than against the tapestries, as many of them have been arranged since the 19th century. It is often in provincial locations where original frames have the best chance of survival; that is, when they are not, perhaps, associated with the most valued or prestigious paintings in a collection, which are always more liable to updates into fashionable contemporary styles.

Unknown artist, Henry VI (1421-71), c. 1540, o/panel, 12 1/2 x 10 ins (31.8 x 25.4 cm.), oak frame engaged with panel, National Portrait Gallery

These frames are compared with an early original frame on a portrait of Henry VI in the National Portrait Gallery, dating from about 1540. The structure of this is described by Jacob Simon:

‘… the frame was made separately from the panel, but it was designed so that the panel fitted into grooves cut in the edge of the frame, the four sides of which engaged with the panel before being fixed together with wooden dowels. Once the frame was assembled and decorated, it was very difficult to remove the panel without damaging the frame.’ [21]

Moveable versions of these simple frames replaced the engaged version from the 1540s, so the example above is a late flourish.

Armorial panel with the arms of Shrewsbury & Hardwick, verre églomisé, before 1601, overall dimensions in ebonized oak cassetta 18 7/8 x 15 3/8 x 2 1/8 ins (48 x 39 x 5.25 cm.), NT 1128215

A related design from the end of the 16th century is original to the panel of armorial verre églomisé it frames; here, the grooved interior at the sight edge is constructed to take a slide in front of the glass, as a protection. Similar frames were made for looking-glasses at a time when mirrored glass was still an expensive rarity, and might be painted in various decorative ways; later, of course, slides and hinged panels were deployed to conceal paintings which might be (as it were) rather outré in a domestic setting…

British School, William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Devonshire, 1625-26, o/panel, 30 x 241/2 ins (76.2 x 62.2 cm.), NT 1129096

Ebonized and parcel-gilt frames were still common well into the 17th century, as shown by the portrait of William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Devonshire, in an original or contemporary frame; however, the reign of Charles I brought a greater consciousness of fashionable European styles of framing, a movement from the plain cassetta to carved decoration, and the introduction of gilding overall.

Claude Déruet (after; 1588-1660), Louis XIV as a child, c.1642, o/c, 28 1/3 x 22 1/3 ins (72 x 56.7 cm.), NT 1129147

British School, ? William Cavendish, 3rd Earl of Devonshire, 1630s, o/c, 23 x 19 ins (58.4 x 48.3 cm.), NT 1129143

There are three gilded Auricular frames in the Hardwick collection, all fairly small. The two illustrated above are of almost identical pattern, idiosyncratically carved with wings – a less common motif than, for instance, marine ornaments. They have winged mascarons at the top centre, winged lions’ heads at the bottom, and wings at the top of each lateral rail; the latter motif is also found on the frame of The Paston Treasure. These are contemporary, and probably original to, the pictures they house.

Sir Peter Lely (in the manner of; 1618-80), Unknown man, c.1645-50, o/c, 73.5 x 60.5 cm., NT 1129145

The third is a pattern associated with paintings by Lely of the 1650s and early 1660s – it

‘… is found so often on his work of the period, and more often on his work than on other artists’, that it is possible to suggest that the type was much favoured by him. ‘ [22]

It is also idiosyncratic, having voluted snailshell corners, two spiral shells on a cord at the top centre, a bat-winged mascaron at the bottom centre, and fanned leaves and scallop shells at the lateral centres.

Sir Peter Lely, Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich, c. 1655-59, o/c, 30 x 25 ins (76.2 x 63.5 cm.), National Portrait Gallery, London

A good example frames Lely’s Edward Montague, 1st Earl of Sandwich, from which it is possible to see what Christopher Rowell is too tactful to point out in the book – that at some point in the past a conservator or curator, unfamiliar with the various incarnations of the Auricular, has fitted the Hardwick portrait upside-down in the frame.

Lely (manner of), Unknown man, c.1645-50

The painting has therefore been out of this frame at some point, and thus there is a chance that the latter may belong to another portrait, either in the Hardwick or Chatsworth collection.

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (attrib.; 1561/62-1635/36), Lady Frances Maynard, née Cavendish, c.1613, o/panel, 34 1/2 x 31 ins (110.5 x 78.7 cm.), NT 1129107

Other 17th century frames picked out for notice include a torus frame with garland decoration, halfway between the simple British cushion frame and a Louis XIII-style bunched leaf frame, both from the second third of the century. This, on Lady Frances Maynard, but about forty years later than the portrait, has alternating bunched bay and oak leaves separated with berries and acorns, centred on all sides and bound at the corners. It is at once simple and slender, but also rich.

Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646/49-1723), William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Devonshire, c.1690, o/c, 28 3/8 x 22 ins (72 x 56.5 cm.), NT 1129210

A fully-developed Louis XIII-style frame contains an oval portrait of the 1st Duke of Devonshire by Kneller. This frame has the characteristic back moulding (flowered), a garland on the top edge, a cavetto or hollow, a spiral ribbon moulding, and a leaf-tip at the sight edge; the combination of all which gives the whole more breadth and variety than the earlier frame. The garland on the torus is carved in deep relief and with considerable refinement; it has a sunflower at the crest, from which the garland depends on each side. This is composed of leaves and wheat ears at the top, roses, bellflowers and poppies, all of which are strung on a ribbon. It lends sparkling animation and depth to the portrait. At least three other portraits are set in variations on this frame [23].

John Baptist Closterman (fl.1690-1713), John Manners, 1st Duke of Rutland, c.1703, o/c, 85 x 56 ins (215.9 x 142.2 cm.), NT 1129220

British School, Lady Diana Cecil, Countess of Elgin, 1624-25, o/c, 80 x 47 3/4 ins (203.2 x 121.3 cm.), NT 1129100

Another interesting group of frames from the late 17th-early 18th century seems to have developed from a confluence of Baroque styles, including Roman frames, French Louis XIII frames, and British panel frames. The deep sculptural profile is highly Baroque; the densely carved and intertwined foliage and flowers of the projecting corners is more three-dimensional and undercut than is perhaps usual for British techniques, and may indicate a Huguenot craftsman. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes had taken place relatively recently, in 1685, and London had already offered sanctuary to a large number of French Protestant migrants fleeing persecution. Britain gained immensely from this influx, with an injection of highly valuable skills – weaving and carving being only two of the more obvious. Christopher Rowell notes that these frames are associated with ‘five full-length portraits, clearly from a larger series and framed identically’, and that another had been commissioned independently, after 1692, for Chippenham Park in Cambridgeshire, by the Earl of Orford [24].

Isaac Whood (attrib.; 1689-1752), Queen Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach & her son, c.1730, o/c, 49 x 39 ins (124.5 x 99.1 cm.), NT 1129123

‘The most spectacular frame at Hardwick is the carved and gilded surround of the portrait of Queen Caroline… At first sight, the frame of the double portrait appears to be French, but it is carved in pinewood, which is rare for French frames, and the distribution of the various decorative elements is not quite convincing.’ [25]

Here, too, the possibility of an immigrant Huguenot framemaker may well be the solution to French workmanship in English wood. It is certainly a beautifully carved object in Régence style, with foliate-&-shell corners, lambrequin centres, and a fronton held in two rocaille C-scrolls, which are avant-garde compared with the rest of the frame.

Nicolas de Largillierre (1656-1746), Sir Robert Throckmorton, 4th Baronet, 1728-29, o/c, 53 3/4 x 41 1/4 ins (136.5 x 104.8 cm.), Coughton Court, NT 135620

It is compared in the book with the frame of Largillierre’s portrait of Sir Robert Throckmorton at Coughton Court; but – as Peter Cannon-Brooks has pointed out – this (and those for the portraits of Throckmorton’s three sisters) were made for the client in Paris:

‘It is an interesting reflection on Parisian taste and patronage during the 18th century that so many of the exceptionally rich frames were carved for foreign clients, and indeed there is evidence that these slightly exotic – some would say ‘over the top’ – frames are characteristic of foreign patronage in Paris.’ [26]

It is indeed exceptionally rich; it is also in full-blown Louis XV style with swept sides and a massive sculptural fronton. Together, the Hardwick frame and the Coughton Court frame seem to illustrate most clearly the difference between a frame probably made in England by an immigrant worker harking back to the style and vocabulary of his home at the time he left it, and a frame definitely made in Paris in a hyper-decorative version of what was currently most fashionable.

Two further chapters deal with the treatment of Hardwick in the 19th and 20th centuries by Bess’s descendants; particularly by the 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), to whom the house itself (and various mistresses) stood in the stead of family. He was an inverterate collector, antiquarian, refurbisher, re-hanger, re-arranger, and the creator of an historical vision of Hardwick.

British School, Queen Elizabeth I, 1592/98/99, o/c, 88 x 66 1/2 ins (223.5 x 168.9 cm.), NT 1129128

He must have gone in for a good deal of reframing, too (as did his successors): he

‘…preserved numerous historic textiles by framing and glazing them with mouldings from rooms he had dismantled at Chatsworth… These mouldings were sometimes used for picture frames. The flamboyant full-length portrait of Elizabeth I, which had belonged to Bess of Hardwick, was provided with a massive version of this egg-&-dart pattern, very much in an antiquarian spirit. The duke declared that he had adorned ‘Queen Elizabeth with a frames of the eternal Chatsworth mouldings.’ ‘[27]

Hans Eworth (follower of; c.1525-post 1578), Elizabeth Hardwick (‘Bess of Hardwick’), c.1560-69, o/panel, 34 1/2 x 26 1/4 ins ( 87.6 x 66.7 cm.) NT 1129165

Bess herself also came in for an upgrade, either because what was almost certainly one of the simple parcel-gilt and ebonized cassetta-style frames was too dilapidated, or because it was thought not splendid enough for the founder of the house. Her Victorian revival French Régence-style frame, wide and ornate and gilded overall, almost certainly dates from the lifetime of the 6th Duke, possibly from the 1850s. It is wildly anachronistic, but even collectors of the duke’s antiquarian cast seem to have taken little account of genuinely antique frames.

? Rowland Lockey (c.1565-1616), Elizabeth Hardwick, Countess of Shrewsbury, post-1590, o/c, 40 ¼ x 30 ¾ ins (102.2 x 78.1 cm.), NT 1129102

However, with another portrait of Bess, twenty-thirty years later in her final widowhood, some effort – however inaccurate – was made. This frame dates from after 1865, when the painting was seen by George Scharf of the National Portrait Gallery; he recorded that it was in a ‘plain black moulded frame’ [28]. The reframing is based on a late 17th century panel frame, often called a ‘Lely’ frame by association, but it has been turned inside-out, so to speak: in the antique original of the pattern, the cavetto lay within the main torus moulding, with ornamental mouldings at the sight edge [29]. Ford Madox Brown and Millais both used revivals of the panel frame – Brown for paintings with historical English subjects . As re-imagined for Bess in a black and parcel-gilt bolection form, it gives the portrait definition against the tapestries in the Long Gallery, where portraits were increasing hung during the 19th century, as well as an ‘historical’ context and a greater richness of ornament and gilding compared, again, with the 16th century Hardwick cassetta-style.

Unknown artist, Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury, probably 17th century, o/c, 38 7/8 x 31 ins (98.8 x 78.7 cm.), based on NT 1129102, National Portrait Gallery

It can be contrasted with the framing of a copy of the same picture in the National Portrait Gallery, which had an inventive Tudoresque pattern devised for it the year it was acquired, by George Scharf, subsequently director of the Gallery, after his visit to Hardwick [30]. It was made by Henry Critchfield, who worked for the NPG from 1861-80 ; it is carved, parcel-gilt, and cost £3.10s [31].

David Cox (1783-1859), The Gallery, Hardwick, looking north, 1839, w’colour, 303/8 x 423/8 ins (77 x 107.5 cm.), Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth

One of the main windows onto picture frames at Hardwick in the 19th century is through the interior views, especially of the Long Gallery, which were produced by various artists, and many of which are published in the book. In the view above, painted by David Cox as the central and largest scene in a triptych of different views of the Long Gallery, the portrait of the widowed Bess with her long pearl necklace can be seen in its ‘plain black moulded frame’, before the revival panel frame replaced it (fourth from the left, on the bottom tier). The hanging is close and jigsaw-like, with up to five smaller or three larger pictures layered above one another, so that very little of the tapestries beneath are visible.

Joseph Nash (1809-78), Gallery, Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire, 1840, hand-coloured lithograph, 12 x 17 ins (30.5 x 43.2 cm.), art market

In a lithograph by Joseph Nash of a year later, there is a slightly different hanging, with the portrait of Bess at the extreme left-hand edge of the image, shifted much closer to one of the chimneypieces. In this view, the window at the end of the Gallery is still visible, whereas in the watercolour by Cox, it has been blocked up and hung with more paintings by the 6th Duke.

As with Ham House, Hardwick Hall is the product of its centuries of occupation by owners who have constructed different versions of their own history and that of the house in the ways they have decorated, redecorated, altered, rehung and reframed. This book is a magnificently various and thorough examination of the whole, its assemblage of chapters like facets set aslant from each other to create a four-dimensional impression of a building and its collection through time. All of the fine and decorative arts find their own space in here – and frames and borders are not the least of these.

Decorated wall panelling, High Great Chamber, c.1610, oak, with carved pilasters & painted strapwork panels, NT1129857.1

*************************************************************

Singing the Eglantine Table:

*************************************************************

[1] The Chatsworth estate had been acquired by the second husband of Bess of Hardwick, Sir William Cavendish; they began a new house there in 1553, and Bess completed it after Sir William’s death in 1557. It passed to her eldest son, Henry Cavendish; Henry sold it to his brother William, the 1st Earl of Devonshire, who had also inherited Hardwick. The two estates remained bound closely together; they are about 14 miles apart, near Bakewell and Sutton-in-Ashfield respectively (see map)

[2] Philip Riden’s articles for the Derbyshire Record Society and the Derbyshire Archaeological Journal are given full acknowledgement in the notes and bibliography, for his work on the Hardwick documents.

[3] Details of entablature and supporting capital; engraving in Hans Vredeman deVries, Den eersten boeck, Antwerp, 1565; see Hardwick Hall: A great old castle of romance, p. 43

[4] Many of the rooms have gone under various names over the years, and – unless you know Hardwick intimately – it is not always clear from the text (and even in the index) exactly which room is being referred to, without some frantic underwater doggy paddling backwards and forwards through the book. This is a very minor flaw, however.

[5] Thomas Pennant, 1773, quoted by Nicolas Cooper & Ben Cowell, Chapter 12, Hardwick Hall…, p. 203

[6] Libro estraordinario di Sebastiano Serlio bolognese : nel quale si dimostrano trenta porte di opera rustica, mista con diuersi ordini, & uenti di opera dilicata di diuerse specie : con la scrittura dauanti, che narra il tutto

[7] Hardwick Hall..., op. cit., p. 22. The Mary, Queen of Scots armorial tympanum over the door is a later addition, bolstering the fiction that Mary had been imprisoned at Hardwick.

[8] Hardwick Hall..., op. cit., p. 51

[9] Ibid., p. 55

[10] Ibid., p. 209

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., p. 210

[13] Ibid., p. 213, & see note 17 to this chapter: (on a version recorded in France, possibly from Charles I’s collection) ‘… The description in Louis XIV’s inventory closely matches the borders on surviving Supper at Emmaus tapestries in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, and St John’s College, Oxford…’ (p. 221)

[14] Ibid., p. 116

[15] Ibid., p. 124

[16] Ibid., p. 125

[17] Ibid., pp. 88-93

[18] Ibid., pp. 96-98

[19] Ibid., p. 151-53

[20] Ibid., p. 341-45

[21] Jacob Simon, The art of the picture frame, 1996, National Portrait Gallery, p. 31

[22] Ibid., p. 92

[23] Hardwick Hall..., op. cit., p. 343

[24] Ibid., p. 343-44

[25] Ibid., p. 345

[26] Peter Cannon-Brooks, ‘Tournières, Bateman and two picture frames’, International Journal of Museum Management & Curatorship, Vol. 4, no 2, June 1985, p.145

[27] Hardwick Hall..., op. cit., p. 260

[28] Jacob Simon, op. cit., p. 180

[29] This design has been used for other portraits in the Hardwick collection – on those of Mary, Queen of Scots and Lady Arbella Stuart, for instance.

[30] Ibid., pp. 113, 116 & 179-80

[31] Ibid.