Restoring a Grinling Gibbons frame

Jevon Thistlewood, paintings conservator at the Ashmolean Museum, describes the process of restoring an extraordinarily delicate and attributive frame by Grinling Gibbons to its original 17th century appearance.

John Riley, Elias Ashmole, 1683, carved & gilded frame by Grinling Gibbons (WA1898.36), prior to recent restoration, in the former Founders Gallery, © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

On 2 February 1683, Elias Ashmole (1617-1692) wrote in his diary, ‘My picture (after sent to Oxford) came home.’ [1] He was referring to a portrait since attributed to John Riley [2]. A new building was nearing completion in Broad Street, Oxford, which would house Ashmole’s Museum on the top floor, with a School of Natural History below and a laboratory for chemical experimentation in the basement [3]. The Museum opened to the general public on 6 June 1683 [4], and after visiting it on 17 July 1683, Sir Thomas Molyneux wrote to his brother:

‘The Museum Ashmoleanum is the highest; the walls of which are all hung round with John Tradescant’s rarities, and several others of Mr Ashmole’s own gathering; his picture hangs up at one end of the room, with a curious carved frame about it, of Gibbins his work.’ [5]

This is a very early account of the portrait, and – whilst Molyneux does not elaborate on it – he does draw attention to the frame and its creator. There was clearly interest in and a certain cachet to the work of Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721). In the preceding year Gibbons had commissioned Ashmole to cast his horoscope [6], and it is sometimes suggested that the frame was provided as payment for this. Whether or not this is true, it does at least document a working relationship between the two men.

John Smith after Sir Godfrey Kneller, Grinling Gibbons (WA1863.1193), © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Robert Plot, the first Keeper of the Museum’s collection, was also the Professor of Chemistry, through these rôles forming a connection between museum, teaching and laboratory. In preparation for a catalogue, he wrote the following entry for the portrait and frame in 1685:

‘Pictura venustissima ornatissimi viri Dni Eliae Ashmole hujus Musæi instructoris munificentissimi, Limbo e Tiliâ arte prorsus Thaumaturgicâ cælato, adornata.’

(A very beautiful picture of that greatly distinguished man, Master Elias Ashmole, the most munificent founder of this Museum, adorned with a lime-wood frame, carved with an art truly miraculous) [7].

In contrast to his other frame entries Plot does not mention gilding, and his praise suggests that this frame is worthy of exhibition status in its own right. In a museum of man-made and natural wonders from around the world, Gibbons’s work was given a prime position on Ashmole’s portrait. I would suggest this deal suited both men well. The extent of the known world is also reflected in some of the plants represented on the frame.

To be thorough, I should also mention Celia Fiennes’s visit between 1689 and 1702 (although there is some question as to the accuracy of her description). She noted that,

‘…there is the picture of a Gentleman yt was a Great benefactor to it being a travailer; the fframe of his picture is all wood carved very finely with all sorts of figures, leaves, birds, beast and flowers’ [8].

Whilst the birds and beasts were misremembered, her description does indicate that this frame was of particular note, and that such carving was expected to be seen ungilded, in the wood.

Given Ashmole’s royalist loyalties, it is perhaps unsurprising that both Riley and Gibbons had worked for the King. Riley had painted several portraits of Charles II [9], whilst Gibbons had worked at Windsor Castle, completing the Cosimo panel by 1682.

John Riley, Elias Ashmole; detail of the lace cravat © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Riley’s portrait appears to have a coincidental comparison to Gibbons’s carving, for instance in his execution of Ashmole’s stiff lace cravat. Whilst very much of the fashion, it appears to be particularly columnar, in comparison with similar falls of lace in other works by Riley. Is it possible that Riley had Gibbons’s work in mind – perhaps specifically the cravat he carved from wood, and which was owned by Horace Walpole? [10]

Amongst Gibbons’s other works, the Ashmole frame appears to show a development in style related to overmantels [11]: the vertical arrangements in particular are densely packed, and yet there is separation between the groups of objects. Key to maintaining continuity between these groups is the tumbling drapery on either side. These motifs re-appear in his work of a decade or so later, to different effect and without the added complication of a decorative border to contend with. The frame has a general, rather than a strict symmetry, perhaps revealing more input from the master carver rather than his assistants. It is constructed from four lengths of limewood in which forms have been carved to a depth of up to 55 millimetres. This is perhaps most impressive in the ‘acanthus whorls’ [12] at the top of the frame. In several places an additional layer of limewood has been added, where elements are required to project up to 65 millimetres further forward. Undercutting and surface refinement has been restricted to those areas which can be seen. Not only did this reduce the amount of work required, it also provides much needed support to what appear otherwise to be delicate floating forms.

In 2011, painting and frame were removed from display in the Ashmolean for urgent conservation work. Of most concern with regard to the frame was the integral strength of the top member, which had long ceased to support its own weight and was close to serious failure. This was principally due to the many historic repairs which had been carried out using animal glue, strapping or plaster around metal rods which were failing. Access to remedy these was hampered by a second feature of the frame, namely the much-debated, thick, lumpy gold coating, which had often been described as gold paint.

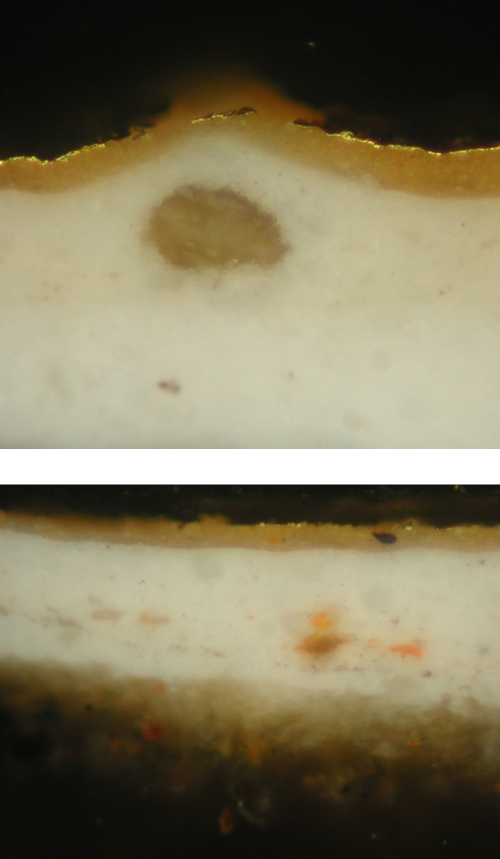

A flaked loss from the frame turned upside-down to view the surface which has detached from the wood [13] © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

A flaked loss from the frame turned upside-down to view the surface which has detached from the wood [13] © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

This seemed an opportune moment to examine the finish of the frame, and fortuitously there were extensive losses and flaking along top edges which easily provided samples. These were taken from various areas of the frame and examined in cross-section. They revealed that the frame had been oil-gilded over white paint, which had been thickly applied to the greasy, sooty surface of the limewood. There was no evidence of earlier layers beneath the soot, nor of toning over the gold.

A representative sample from the frame shown in cross-section © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Looking at the layers identified in the sample, the first was a sooty layer deposited on the surface of the limewood. The Museum in Broad Street had been dependent on coal fires for warmth until the end of 1885, when a hot water heating system was installed. Some improvements had been made by moving to closed systems of heating, but essentially coal burning was still the main source of warmth. Under William Huddesford’s keepership [14], ‘some [objects] at least fell victim very quickly to the sulphurous atmosphere in the early Museum, promoted by the open coal fires’ [15].

A view of the ground floor of the Museum, c.1870, showing the framed portrait high above a fireplace © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

At some point after 1833 the display of the collection was reorganised and expanded over two floors, and in a photograph of around forty years later we can see the portrait and frame hanging high above a large fireplace on the ground floor. This was one of the few paintings that was prominently displayed, as around the mid nineteenth century it was considered that ‘…the paintings, so foreign to the purpose of the museum, if they must be retained, should be more condensed’ [16].

A detail of the frame during conservation showing the limewood ingrained with soot in places © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Over this sooty surface, the frame had been thickly painted with a lead-based white paint [17]. The limewood had been attacked by insects at some point, and there were holes which were either filled with paint, or, to a lesser extent, open, which suggests that the paint was applied after an insect attack, but that some insects had managed to escape. This chimes in with comments made regarding the white paint on Gibbons’s carved reredos in the Chapel of Trinity College, Oxford (c.1694):

‘To paint or varnish good carving is indeed barbarous… At the same time, whatever may have been the treatment here, the carvings appear to have made since a good recovery. The reredos indeed may have been saved from woodworm.’ [18]

On the same subject Tipping noted that,

‘…what is not dark and shiny is white, for a coat of paint of that colour hides all the delicacy of touch of the magnificent limewood carvings about the altar…[19]

In fact, Tipping has many more examples of Gibbons’s work which had subsequently been over-painted, stained or varnished. There are therefore connections being made between paint being used to prevent insect damage, and the same paint concealing fine detail [20]. In 1855 we know that the Museum had a problem with worm-eaten specimens, because the underkeeper George Augustus Rowell was boiling them in a ‘solution of thin size and tobacco water’ and when dry, brushing them with ‘size and corrosive sublimate’ [21]. It is also worth noting that timber wainscoting around the walls of the lower floor was removed, along with the oak partitioning, in the 1833 reorganisation [22].

Two cross-sections showing lead salt development © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Samples in cross-section show that the white paint had developed lead soaps [23] which had resulted in small protrusions, producing a gritty surface.

An exhibition label attached to the reverse of the painting © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In 1866 the portrait was included in The First Special Exhibition of National Portraits ending with the reign of King James the Second on loan to the South Kensington Museum [24]. This is the first time that the work had been seen in the context of a picture gallery, and thus is the most likely occasion for the requirement of a gold finish on the picture’s frame.

A detail of the frame showing the gritty surface © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The oil size and gold leaf were applied directly to the white paint and have taken up the surface characteristics of the gritty, painted layer.

During the late 19th century there appears to have been a re-evaluation of the frame’s attribution to Grinling Gibbons. This is illustrated by Charles Francis Bell’s 1898 description [25] of it as being ‘carved in high relief in the manner of Grinling Gibbons and gilded’ [26]. Notably, this is the first recorded mention of the frame’s being gilded and it is clearly more restrained in enthusiasm than the earlier ‘splendid specimen of the carving of the famous Gibbons’ which appears in Philip Bury Duncan’s catalogue of 1836 [27]. It is my belief that the over-painting and gilding of the frame were connected to, if not responsible for, the subsequent re-appraisal of quality.

Tim Newbery working on the frame

In 2013, with support from The Idlewild Trust, The Leche Trust and the van Houten Fund, Timothy Newbery was commissioned to lead the restoration of the frame.

A cleaning test carried out to investigate the removal of layers of oil gilding and white paint © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

This included urgent repairs to broken and missing sections, in conjunction with the removal of the white paint and oil-gilding.

A detail of the frame during restoration © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Isolated sections of insect damage were successfully consolidated without saturating the surrounding limewood. The restored frame is self-supporting once more. It has a darkened appearance from many years of natural seasoning, and yet it still provides a lighter contrast to the dark brown background of the portrait. In short, the painting and the frame appear to work well together following restoration.

The shield at the crest of the frame, together with the figures of Mercury [28] and the twins of Gemini [29], warrant a special mention. The combined unit was carved from a separate piece of wood and incorporated to sit neatly above a string of lily-of-the-valley flowers and amongst acanthus stems. The arms displayed are those of Ashmole [30] quartered with those of his father-in-law, Sir William Dugdale [31]. The shield is the only area where sampling uncovered an earlier scheme of decoration. It is unsurprising, given that Ashmole was a former Windsor Herald, that he had the arms accurately painted with the appropriate colours. However, when the frame had been over-painted and gilded, a mistake had been made in repainting the Dugdale arms which would have been unthinkable to Ashmole himself [32]. A background intended to be silver was now gold. Sadly, it was neither possible or safe to reveal the original decoration, and in any case the silver appeared to be mostly blackened.

The heraldic shield after restoration © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

However, to give some sense of the original colours, a reversible silver finish was applied to the background on the right-hand side. Curiously, it was possible to reveal one small element of early gilding. The motto ‘Ex Uno Omnia’ beneath the arms had escaped the white paint and oil-gilding, and instead had been overpainted black, presumably to increase legibility. With appropriate testing, it was possible successfully to remove the black overpaint.

Wooden wedge inserted behind the heraldic shield on the crest of the frame © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

At some point the top of the shield had been forced forward by inserting a wooden wedge from behind. This seems to have been done to make the shield tilt forward and become more legible when seen at a greater height than originally intended. This could also explain the black overpaint added to the motto; and, as we can see in the c. 1870 photograph, the frame and portrait were displayed as high as possible, close to the ceiling. This tilting of the shield had meant that nearby sections of the acanthus were broken and moved to create the necessary space. The numerous breaks were then re-joined out of alignment, considerably undermining their intended function in the support and distribution of the central weight in the top member.

Repairs to acanthus sections © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

These acanthus sections were taken apart, repaired and reconstructed, and to allow correct alignment and function, the shield was moved back to its original position.

Detail of the carving showing a Turk’s Cap lily flower below that of a camellia © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

As details emerged during restoration, the various species of plant included in this work were identified by flower, leaf, fruit and pod. The total number is particularly high, with as many as fifty species from the 17th century appearing [33] – amongst his many interests, Ashmole included botany. Although the majority of the plants identified were established in England, there are a few from further afield such as cedrela from the Caribbean and Central and South America, camellias from East Asia, and freesias from Southern Africa. These plants highlight both the international trade in plants and the extent of the known world; and links can therefore be made with the Tradescants, who were both royal gardeners and great plant-hunters during the 17th century.

Detail of the carving showing the isolated Virginia spiderwort flower © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Ashmole was particularly indebted to John Tradescant the Younger for much of his founding collection for the museum. An isolated flower of the Virginia spiderwort (Tradescantia virginiana) on the left of the lower edge of the frame must surely be a direct reference.

Detail of the carving showing the flower of the tulip tree turned away from the viewer © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Nearby there is the flower of John Tradescant the Elder’s tulip tree turning away from the viewer.

The temporary gallery display Ex Uno Omnia on view during 2014 in the Ark to Ashmolean Gallery © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In 2014 the frame was central to a temporary gallery display organised and supported by the University Engagement Programme. Ex Uno Omnia: ‘Everything Out of One’ was a collaborative project with six postgraduate students from Oxford University who were invited to study the frame from a variety of perspectives in parallel with its restoration[34].

John Rile (attrib.), Elias Ashmole, with carved frame by Grinling Gibbons (WA1898.36), after restoration, © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The frame and portrait of Elias Ashmole were reunited towards the end of 2014 and are currently on display in the Ark to Ashmolean Gallery.

John Riley (attrib.), Charles II, frame attrib. to studio of Grinling Gibbons (WA1898.39), © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The astute reader will be aware that a few years after the Museum opened, it acquired two portraits, since attributed to Riley, of Charles II and James II. Each was adorned with an oval frame attributed to Grinling Gibbons, but much smaller than the frame for Ashmole’s portrait. In 1685 Plot describes them as:

‘Effigies Serenissimi Principis Caroli 2di Regis Angl etc. Limbo e Tilia elegantissime cælato ac deaurato, adornata

Effigies Serenissimi Principis Jacobi 2di Regis Angl etc. simili Limbo adornata.’

(Portrait of the most serene prince, Charles II, king of England etc., adorned with a lime-wood frame, most elegantly carved and gilded

Portrait of the most serene prince, James II, king of England etc., adorned with a similar frame [35])

John Riley (attrib.), James II, frame attrib. to studio of Grinling Gibbons (WA1898.40), © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Together with evidence from sampling these descriptions show that the oval frames were originally gilded. At some stage later they were regilded over a thick application of lead white paint in a manner almost identical to that described earlier in this article. Of most urgent concern is the dramatic surface cracking which can be found in places on both frames. Understanding more about the original intentions regarding the creation and display of these frames may lead to new understanding of their present condition and future care.

***********************************************

A while ago now, I was invited to write this article about a recent frame project. I would like to make it clear that the views I express are my own unless otherwise indicated. Along the way the project benefitted greatly from the knowledge, thoughts and expertise of many. It is not possible to name every person, but I have tried to provide references where possible. The project is particularly indebted to the work of Peter Cannon-Brookes in his article ‘Elias Ashmole, Grinling Gibbons and Three Picture Frames’. Please note that the images included in this article are all reproduced with the copyright Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

Jevon Thistlewood

***********************************************

Jevon Thistlewood received an MA in the Conservation of Fine Art from Northumbria University in 2000, specialising in Easel Paintings. Previous qualifications include a BSc in Chemistry and a MA in Sculpture Studies from the University of Leeds. In 2007 he joined the Ashmolean as a Paintings Conservator, the first person to hold such a post at the museum which opened in 1683.

[1] R.T. Gunter, The Diary and Will of Elias Ashmole, edited and extended from the original manuscripts, Oxford, 1927, p.124.

[2] In 1898 C. F. Bell (then Assistant Keeper) assigned this change in the attribution with an account of the reasoning in his Description of Portraits in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford in the Ashmolean Museum Archive, File AMS 22.

[3] J.A. Bennett, S.A. Johnston, & A.V. Simcock, Solomon’s House in Oxford: New Finds from the First Museum, Museum of the History of Science, Oxford, 2000, p. 14.

[4] R.F. Ovenell,The Ashmolean Museum 1683-1894, Clarendon Press Oxford,1986, p.22.

[5] Sir Thomas Molyneux, Fellow of the King ad Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland; Professor of the Practice of Physic to the University of Dublin in 1717; State Physician, and Physician General to the Army, &c.

[6] e.g in D. Green, ‘Grinling Gibbons: His Work as a Carver and Statuary 1648-1721’, Country Life, 1964, pp. 22-23.

[7] Thanks to Bryan Ward-Perkins (University of Oxford) for this translation from 17th century Latin.

[8] Celia Fiennes, Through England on a Side Saddle in the Time of William and Mary, Field and Tuer, The Leadenhall Press, London,1888.

[9] Regarding one of these, the King is said to have remarked, ‘Is this like me? Oddsfish, then I’m an ugly fellow’. This particular portrait has a very similar arrangement and posture to that of Ashmole.

[10] Grinling Gibbons’s carved cravat is dated ‘post 1682’ in Esterly, ibid.; it is now in the collection of the V & A.

[11] The development of Grinling Gibbons’ overmantels is described by David Esterly, Grinling Gibbons and the Art of Carving, exh. cat., V & A, 1998.

[12] A term taken from Esterly, ibid., p. 185: ‘This vortex impulse in Gibbon’s work takes its most extreme form in his acanthus whorls, those cyclonic forms which seem to flow into their own centre.’ We find a similar use in H.A. Tipping, ‘Grinling Gibbons and the Woodwork of his Age (1648-1720)’, Country Life, 1914, p.195: ‘…convex carving of whorled scrolling’.

[13] The surface where a loss of adhesion has occurred can sometimes provide useful information as to the cause of the failure.

[14] Between 1755 and 1772.

[15] Arthur MacGregor, ‘The Ashmolean as a museum of natural history, 1683-1860’. Journal of the History of Collections 13, no.2, (2001), p. 136.

[16] R.F. Ovenell, The Ashmolean Museum 1683-1894, Clarendon Press Oxford,1986, p.194 & 201.

[17] With thanks to Cranfield University for handheld XRF analysis.

[18] D. Green, op.cit., p. 84.

[19] H.A. Tipping, op.cit., p.146.

[20] To reiterate the point, there is a parishioner’s complaint in 1895 regarding the Gibbons’ font cover in All Hallows church which reads, ‘I never walk by the font without wondering how long the coating of white paint will be allowed to veil the glories of the richly-carved cover … And it is passing strange that it should ever have been desecrated with paint’. See F. Oughton, Grinling Gibbons and the English woodcarving tradition, Stobart, London, 1979, p.118.

[21] R.F. Ovenell, op.cit., p.222.

[22] One of the teaching rooms on the ground floor prior to 1833 can be seen in a lithograph of the Special lecture given by William Buckland in the Old Ashmolean Museum, 15th February, 1823 Post 1833, the ground floor was opened up with columns as shown in an engraving of 1836. See also R.F. Ovenell, ibid., p.202.

[23] Lead fatty acid salts are often observed in cross-sections containing lead-based pigments. I will leave the explanation to others. The result is the development of translucent circular masses in the paint layer which migrate to towards the surface, creating small protrusions. The voids can have associated orange lead salt formation. Small circular craters on the surface may also be an indication that protrusions have been abrasively cleaned away. Further information here.

[24] Catalogue entry number 991.

[25] Bell worked at the Museum between 1896 and 1932 as an Assistant Keeper, then as the first Keeper of the Fine Art Department in 1909.

[26] C.F. Bell, op.cit.

[27] Keeper of the Museum between 1829 and 1854.

[28] Ashmole identified with the figure of Mercury or Hermes, referring to himself by the astrological symbol for Mercury; he also believed that he was born under the planet Mercury. The element has a strong association with alchemy, another of Ashmole’s interests, whilst the god moved between the spiritual and material worlds. The carved figure of Mercury on the crest of the frame has a slot in its right hand which was presumably designed to hold a caduceus, now lost.

[29] Ashmole was born 23 May 1617 and therefore considered a Gemini (with the ruling planet of Mercury).

[30] Quarterly sable and or, a fleur de lis in the first quarter. This was granted to Ashmole after the Restoration to replace his previous arms.

[31] Argent, a millrind cross gules with a roundel gules in the dexter canton.

[32] Peter Cannon-Brookes, ‘Elias Ashmole, Grinling Gibbons and Three Picture Frames’, Museum Management and Curatorship, vol. 18, no 2, June 1999, pp183–189.

[33] Thanks to Stephen Harris and Katherine French (University of Oxford) for all their work in identifying the species of plants around this frame

[34] Content included ‘The Gibbons frame – a window to the man Elias Ashmole’, by Rahul Kulka; ‘The art of stripping’ by Anita Paz; ‘Botany in 17th century Oxford’ by Katherine French; ‘Self-fashioning’ by Lauren Kaufman; ‘Where art and nature meet’ by Dina Akhmadeeva; and ‘A fruitful frame’ by Bethany Pleydell (all University of Oxford). Further information here.

[35] Thanks to Bryan Ward-Perkins for this second translation.