Artists’ frames in pâte coulante: history, design, and method

by Peter Mallo

This study was first published in the Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 56, 2021, pp.160-73.

During the final decades of the 19th century in Paris and London, methods for presenting exhibitions were undergoing a major reconsideration, and frames from this period begin to take on a new rôle both visually and conceptually. This development was driven by artists themselves to indicate that their works represented a new kind of vision. Many of the original frames from this time have disappeared from the walls of collectors and museums, but it is possible to piece together concept and approach through photos, treatises, drawings, catalogues, and the few precious surviving frames.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Woman ironing, 1873, o/c, 54.3 x 39.4 cm., in the artist’s so-called ‘pipe’ moulding, and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

This study focuses on artist-designed frames at the end of the 19th century, many of which are preserved in the Havemeyer collection at the Metropolitan Museum, with a particular emphasis on a material known at the time as pâte coulante, unique in its ability to render extraordinary profiles, some of which could not have been realized by any other method available at the time. Although frames in pâte coulante can be seen surrounding the works of many late 19th century and early 20th century paintings, this study refers to the few superb examples available for study in the Metropolitan Museum and in private collections, which in many cases surround works by Edgar Degas. For artists like Degas, this method became crucial for executing radical frame designs. To reinforce the argument that the process of template-cut pâte coulante granted artists and framemakers the freedom to turn any design into a reliable and serviceable moulding, replicas of period mouldings were recreated using the available historic information, and the results gleaned from this technical study are included here.

Exhibitions and frames shift away from the salon

The year 1874 marks an important turning-point for artists in their challenging of the status quo. It saw not only the first one-man show by James McNeil Whistler in London, but also the inaugural show of the Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc., in Paris, the group which the critic Leonard Leroy would satirically dub the ‘Impressionists’ [1]. Both events reveal the avant-garde taking greater control over the presentation of their work and the context of their art, including the way in which their works were framed.

Both Whistler and the Impressionists claimed to have originated the idea of harmony between painting and frame. In 1873 Degas employed simple frames for a series of pastels titled Répétition de ballet, which one of his most supportive collectors, Louisine Havemeyer, described as being painted

‘…soft dull gray, and green which harmonized the decoration of the scenery and… dresses of the ballerina.’ [2]

J.A.M. Whistler (1834-1903), Symphony in grey & green: The ocean, 1866, o/c, 80.7 x 101.9 cm., with signature & frame dating from 1872-74; Frick Collection

That same year Whistler wrote to the collector George A. Lucas,

‘You will notice and perhaps meet with opposition that my frames I have designed as carefully as my pictures – and thus they form as important a part as any of the rest of the work – carrying on the particular harmony throughout. This is of course entirely original with me and has never been done… and I wish this to also be clearly stated in Paris that I am the inventor of all this kind of decoration… that I may not have a lot of little Frenchmen trespassing on my ground.’ [3]

Although it’s impossible to determine who arrived at the idea first [4], the shared impulse to invent new styles of frames was part of a larger thrust to re-contextualize artworks by reimagining the viewing experience. Finding themselves under-represented at established venues like the Paris Salon in the early 1870s, the Impressionists took issue with many of the practices standardized by the Salon and set out instead to create an entirely new format for exhibiting their works. In an open letter to the jury of the Paris Salon in 1870, Degas suggested six tiers of reform in the presentation of works of art [5]. These reforms related specifically to strategies for hanging paintings, but Degas’s larger goal was to show individual works of art to their best effect. In his closing statement, he urges,

‘In short, once you have satisfied your judges’ pride, be good interior decorators.’

Camille-Léopold Cabaillot-Lassalle (1839-88), Le Salon de 1874, 1874, 32 x 39.4 ins (81.5 x 100 cm), detail, Christie’s, 21 January 2009

One hallmark of the Salon was the large frames it required, usually comprised of a running moulding over which were applied layers of cast classical decoration (fluting, rais-de-coeur, acanthus, etc.). The scale of Salon frames had a very important purpose: when paintings were hung edge to edge, artists relied on the wide frame to create some space between their own and neighbouring paintings.

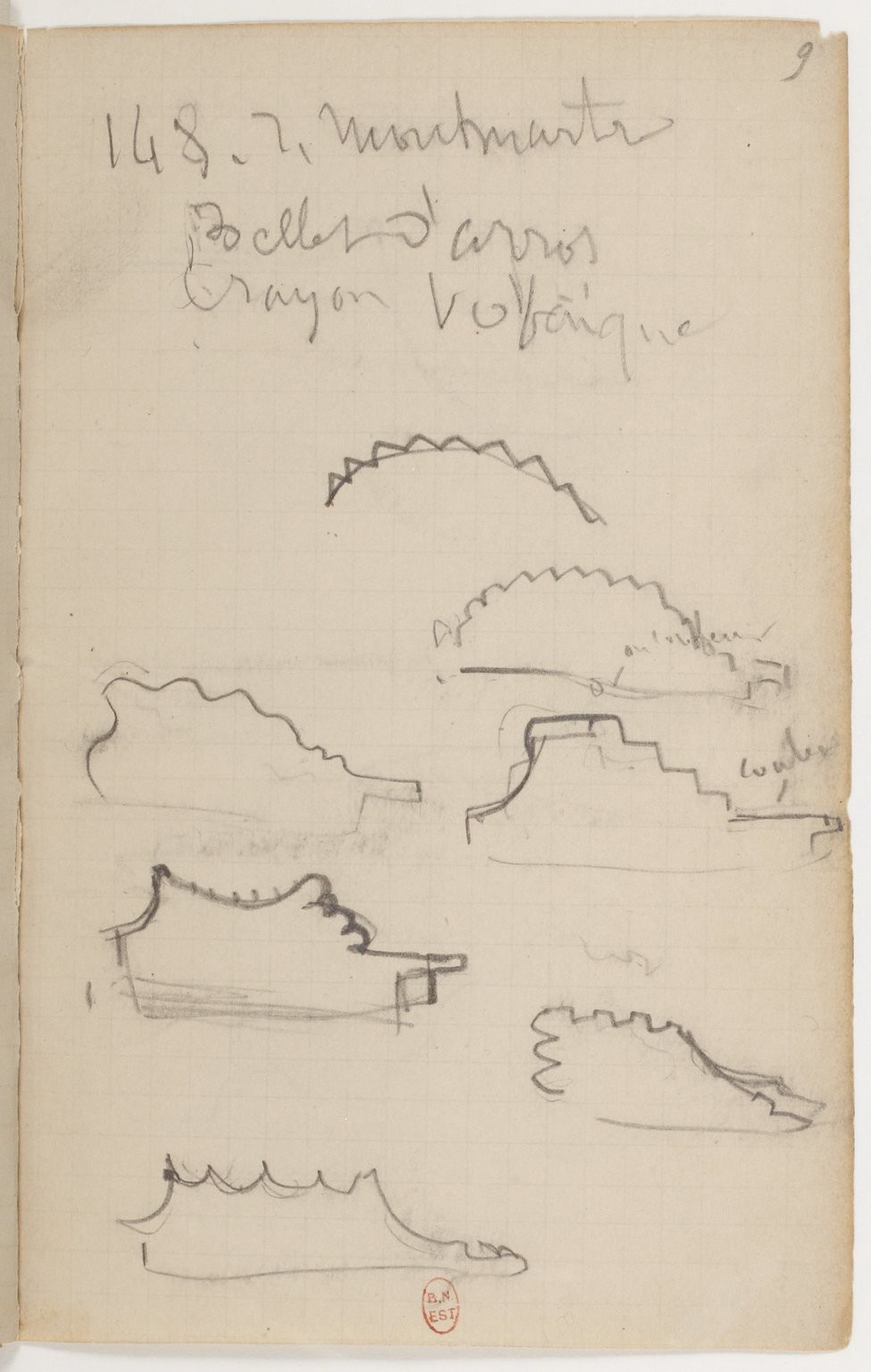

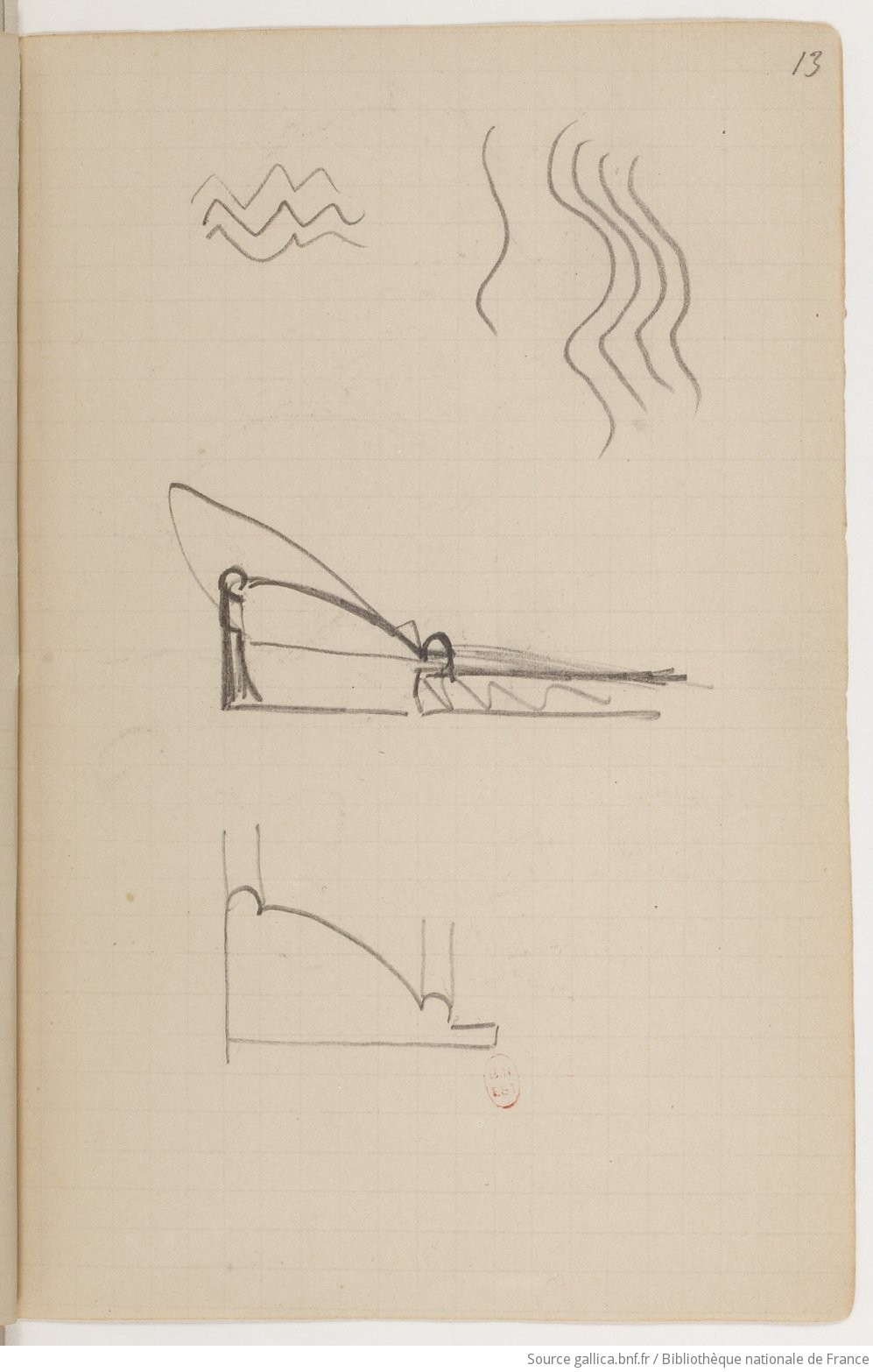

Degas (1834-1917), sketch from Carnet de croquis no 23, Département des Estampes, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Rejecting the Salon system altogether, the Impressionists created their own gallery space, and some of them began conceiving frame styles which would underscore the freshness of their vision: linear running mouldings with no applied decoration whatsoever. At first glance, these experimental frame profiles seem simplistic – even primitive – when compared with the heavily ornamented frames used by their contemporaries in the mainstream. Their formal elegance came from the shapes of the profiles themselves, which were delicately designed to give a sense of harmony between painting and frame through the use of restrained colour and shadow pattern.

Left, façade of the Grand Palais, Paris, completed in 1900; right, a late 19th century finely fluted frame

Degas (1834-1917), Portrait d’amis sur scène (Ludovic Halevy & Albert Boulanger-Cavé), 1879, pastel & tempera/ paper, 79 x 55 cm., and detail; Musée d’Orsay

The most recognizable of these styles are the reeded frames used by Whistler, and the fluted or reeded frames of Degas. They shared formal elements such as reeded friezes and fluted columns with the NeoClassical taste which was informing mainstream frame designs in the late 19th century.

They hearken back, for instance, to the miniature columns found on 15th century aedicular frames, which in turn come from the structural columns of ancient Greek architecture. In frames, as in architecture, these historical elements had traditionally been paired with decorative flourishes, such as protruding acanthus, scrolls, imbricated coin ornament, and other classical motifs which act as focal points. The new styles, by contrast, incorporated only those linear elements which would create a subtle play of light and shadow across the surface of the profile.

Pâte coulante: from necessity to opportunity

Although the shapes we see in the most extreme of these new designs seem very radical, and in some cases extraordinarily complex, they could be made efficiently and at low cost by borrowing a process which had been invented for making architectural mouldings many centuries earlier. This process allowed artists and framemakers to experiment with shapes which could not have been executed in wood, and with a material which was already on hand in framemaking workshops.

Pâte coulante, which translates as ‘flowing paste’, was initially adopted as an inexpensive alternative to machine-milled profiles in wood for running mouldings. The financial woes felt by the Impressionists during the 1870s and 1880s is well-documented, but artists and dealers were not the only ones experiencing economic challenges. During the 1850s and 1860s, under the direction of Baron Haussman, not only was Paris physically reconstructed, but there was also a major shift in the marketplace for luxury goods. One economic result of ‘Haussmanization’ was a trend away from expensive bespoke craft, and towards less expensive mass-produced manufacturing [6]. The framemakers of the period were pressed to find quick and inexpensive ways to keep up with demand for the large ornamented frames suitable for the Salon, and began to use pâte coulante for both cast ornament and template-cut mouldings.

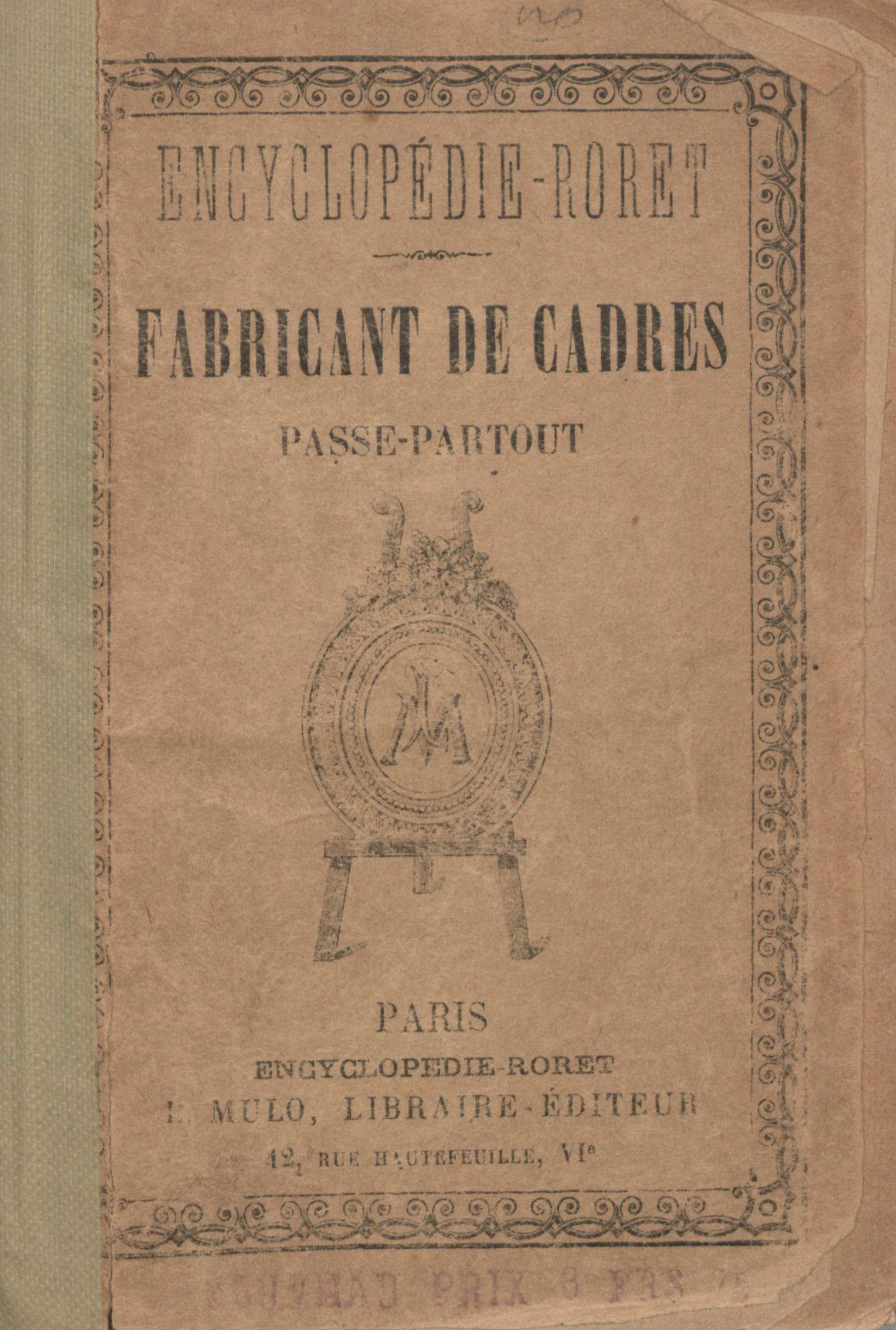

J. Saulo & the Chevalier de Saint-Victor, Nouveau manuel complet du fabricant de cadres…, 1921 ed., Watson Library Digital Editions, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The earliest use of the term ‘pâte coulante’ for framemaking is found in the 1896 edition of Nouveau manuel complet du fabricant de cadres, passe-partout, chassis, encadrement, etc., by J. Saulo and M. de Saint-Victor, published by the widely popular Encyclopédie-Roret. The Manuels-Roret were written primarily for amateurs, but are nevertheless an important asset for outlining popular late 19th century processes in art and agriculture, and gauging when certain processes entered the mainstream. Pâte coulante was not included in the 1850 edition of Fabricant de cadres, so its inclusion in the 1896 edition suggests that the process, which may have been experimental as early as the 1870s, had been widely adopted by the close of the century.

Although pâte coulante appears to have been a relative novelty for framemakers, the practice of pulling a form across a paste-like material via a sled or rail system has its roots in the architecture of classical antiquity [7]. In execution, it also relates to the use of a wave machine for manufacturing ripple mouldings, a style of ornamentation which has come to be associated with 17th century ‘Dutch’ frames [8]. Unlike common architectural plaster, pâte coulante can be built up quickly, is much more durable, able to take a burnish over gilding, and gives the maker extended working time.

Degas (1834-1917), Woman with a towel, 1894-98, pastel/paper, 112.4 x 92.1 cm., and details, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Pâte coulante had additional advantages over composition, or compo, a material used extensively for creating the raised decoration on many 19th century frames. Composition is prepared from chalk, glue, oil, and resin, combined into a stiff, heavy dough and pressed into rigid moulds; it is then transferred to the wooden frame chassis in strips of continuous repeating patterns, or sculpted forms such as acanthus leaves. Compo accepts gilding beautifully, but is very heavy and prone to shrinkage. Pâte coulante was lighter, less expensive, easier to formulate, and resisted shrinking, giving framemakers the ability to manufacture complex mouldings and decoration at a fraction of the cost of wood-milling machines, let alone hand-carving.

The framemaker J. Saulo outlines the basic process:

‘Before we began to make paste frames, the profile was made entirely of wood, even in its smallest details… This method was certainly time-consuming and very expensive, but the product was, by comparison, also much stronger. With progress manifested the need to produce cheaply; we then simplified this work by merely indicating, in the wood, the general sinuosity of the profile. In order to obtain the details, we made iron templates in the modern manner to reproduce the exact profile of the mouldings… It is, as we see, certainly very practical and inexpensive…’ [9]

Although it had been adopted out of necessity to support the mass-production of traditional Salon frames, pâte coulante also opened a path to the production of extremely individualized artists’ frames. And – at the very moment that framemakers had developed a process to render virtually any of the elaborate conventional shapes demanded by the Salon – artists rebelling against the Salon were looking to remake the frame itself. In some cases, artists and framemakers began working together to use this paste-and-template process to realize their aesthetic innovations. Frames designed by artists became extensions of their work, having been drawn by their own hand, cut out in template form, and rendered directly into a running frame moulding.

Frame designs in the new aesthetic

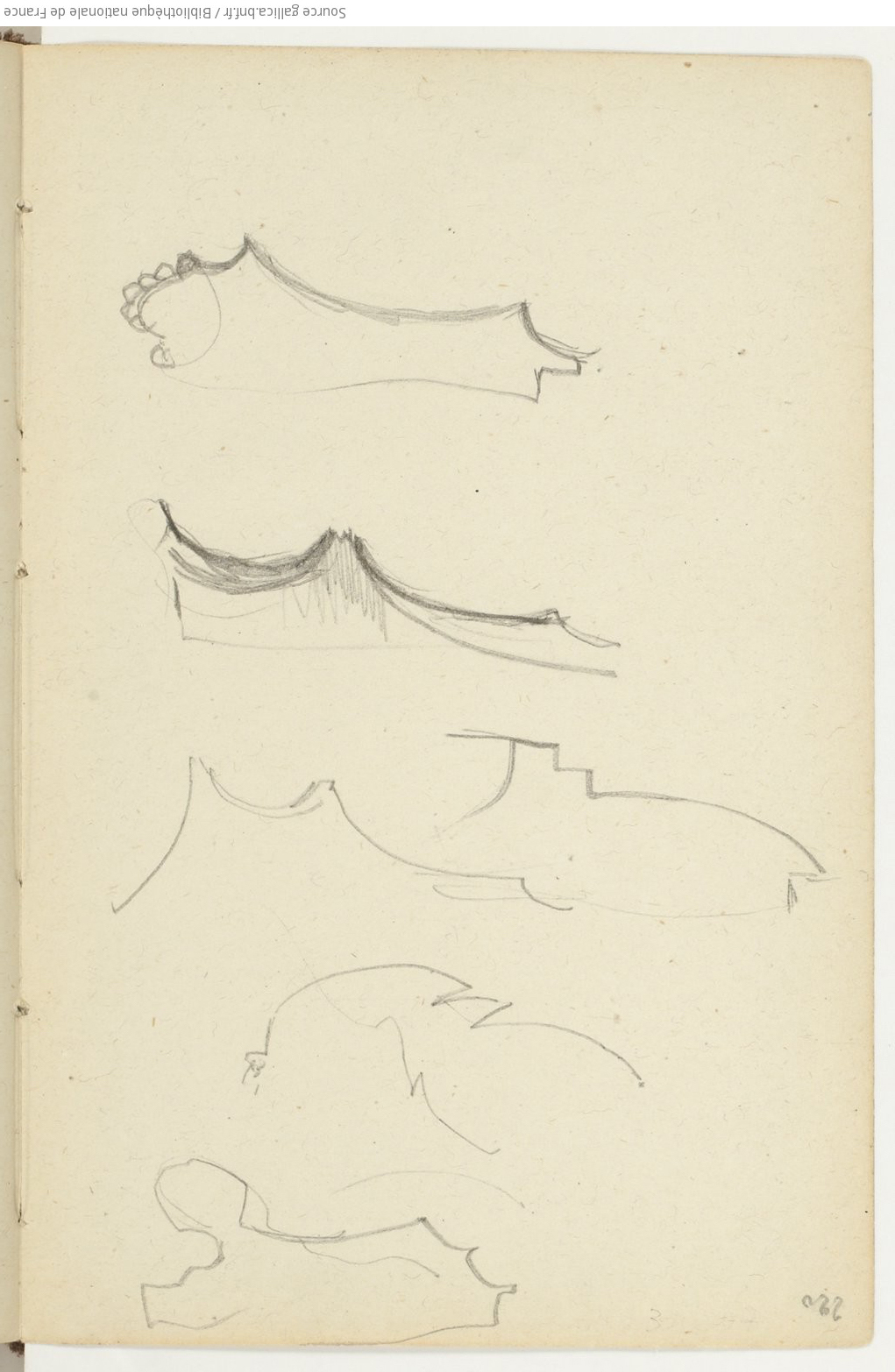

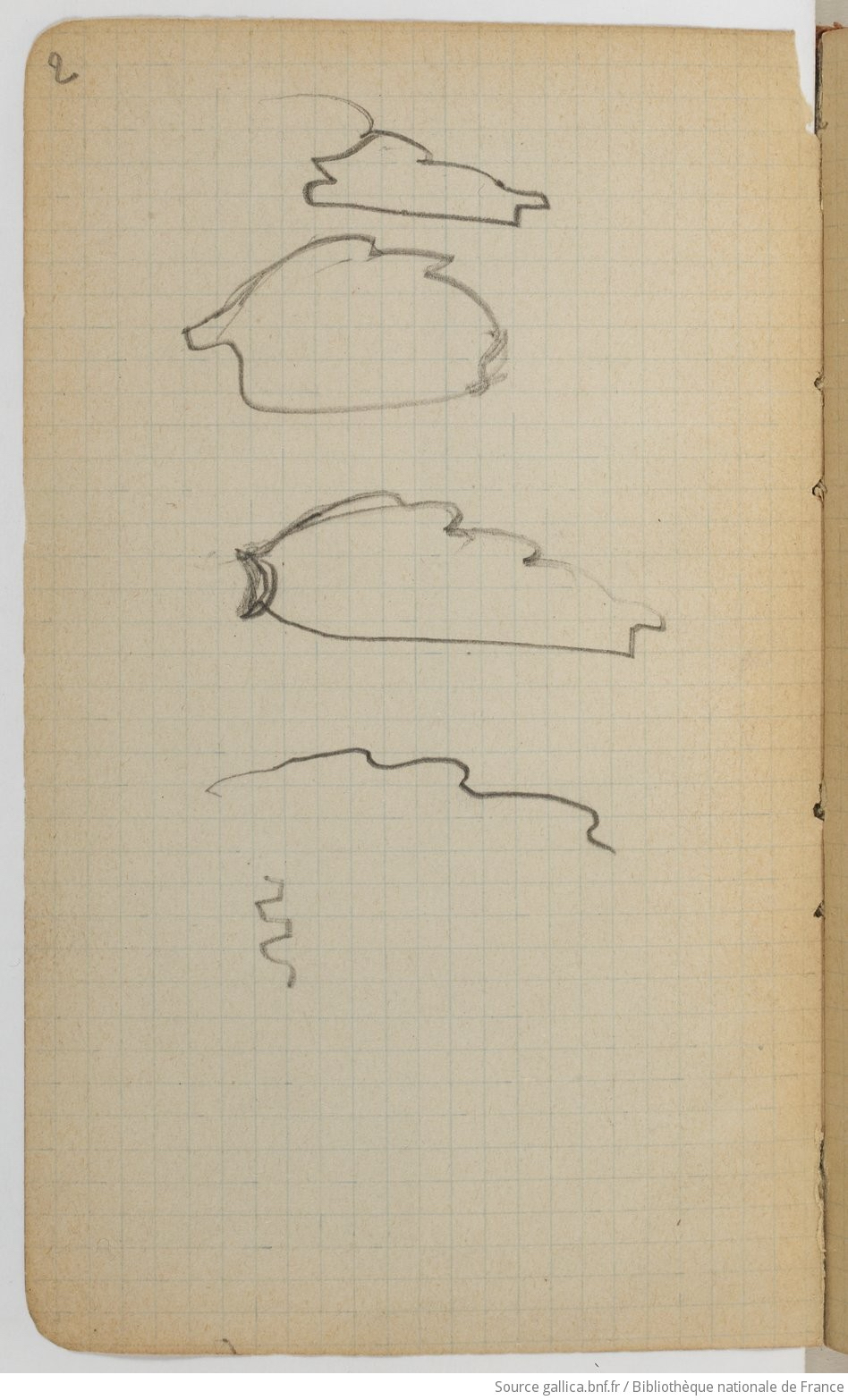

Degas (1834-1917), sketch from Carnet de croquis no 2 (illustrated upside-down), Département des Estampes, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Degas, sketch from Carnet de croquis no 6, BnF

Unlike the heavily ornamented frames used for Salon-style exhibitions, template-cut frames in pâte coulante exhibit an elegant cohesiveness, especially the models associated with Degas in Paris. These mouldings, obviously inspired by his drawings, were conceived as a single contour. Some of the drawings are labored over, others only barely indicated, but all have gesture and a certain flow, as one might sign their name or sketch a silhouette, and could be easily interpreted as a template.

Degas (1834-1917), sketch from Carnet de croquis no 23, Département des Estampes, Bibliothèque nationale de France

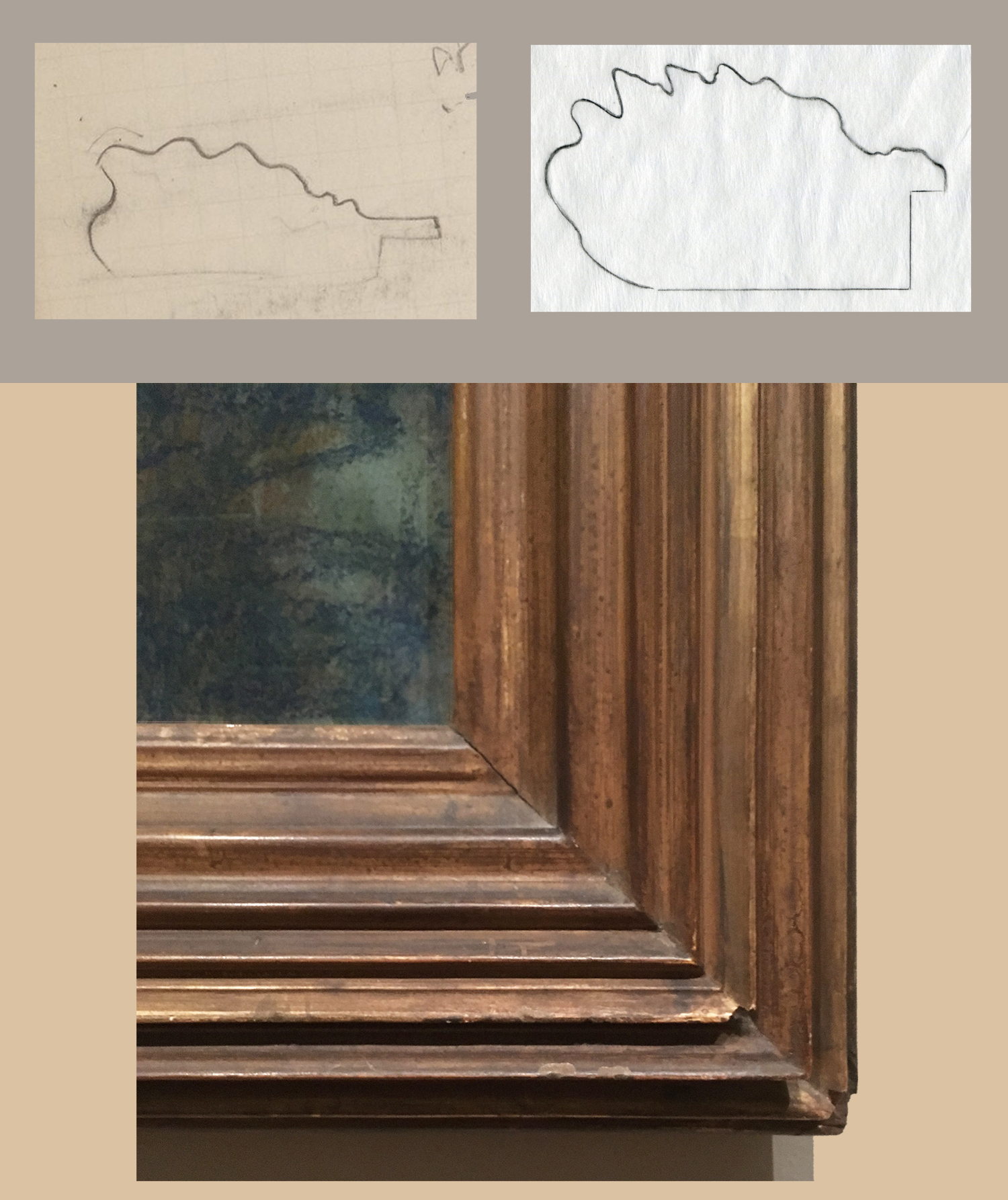

Degas (1834-1917), crète de coq design: upper left, frame profile from his carnet de croquis no 23; lower image, corner of the frame of Woman with a towel, 1894-98; upper right, author’s drawing of the Cluzel frame profile

Template-shaped pâte coulante is well-suited to realize designs which employ the repetition of extremely refined elements: reeds, flutes, and waves, which in turn follow or flow over simple shapes such as flats or cushions. Degas’ crète de coq (cockscomb) design is vaguely cushion-shaped (a convex quarter-round molding, usually symmetrical), yet its features do not repeat; they become more extreme across the moulding from the front to the back, joining soft waves and sharp serrations, and creating extreme variations in the quality of reflected light. Frames like the crète de coq pattern contain deeply curved undercuts coupled with subtle undulations which cannot be made efficiently in wood or composition, giving template-shaped pâte coulante a unique place in the manufacture of running mouldings.

Cluzel’s business, 33 rue Fontaine Saint-George, Paris: the building as it is today, montaged with the shop window, c.1885, with the Cluzel family outside. Photo of 1885 from Frédéric Destremau, ‘Pierre Cluzel…’

Substantial credit is due to framemakers for the development of artists’ frames, certainly for their willingness to support the new aesthetic, and in some cases as potential design collaborators. Pierre Cluzel’s involvement with the avant-garde is well-documented, mentioned by numerous painters in their correspondence, and responsible for producing some of the most iconic designs associated with Degas.

We know from Camille Pissarro’s letters to his son Lucien that Cluzel would show and sometimes sell Pissarro’s paintings from his workshop at 33 rue Fontaine Saint-George in Paris. Cluzel is described by Pissarro as being one of the most skilled craftsmen in Paris [10], and a particularly shrewd businessman [11]. Pissarro was in the habit of ordering his frames through Lucien, and although Pissarro does not seem to have created designs for execution in pâte coulante, their correspondence provides a valuable window onto the relationship between artist and framer/designer, which seemed mostly amiable, with some occasional tension over bills owed and differences in aesthetics. One letter from Camille Pissarro to his son stands out, suggesting that Cluzel would sometimes impress his own aesthetic upon Pissarro’s orders:

‘I did have some borders made in the English style by Cluzel, but as always, Cluzel had the fancy to add to these matte oak borders a white margin in relief on the painting… it cast a shadow on the canvas which is most unpleasant…’ [12]

Label of Pierre Cluzel (1850-94), over-stamped by his successor, L. Vivien, and so dating from shortly after March 1894 when he died; from a frame on French School, Female nude, c.1895, Balclis online auction site, Lot 3099021

The relationship of Degas and Cluzel also merits mention in connection with the evolution of designs associated with Degas. Due to the outstanding amount which Degas owed Cluzel on the latter’s death in 1894 [13], we know that Degas patronized his workshop regularly. Maison Cluzel is mentioned in only a few of Degas’s letters to his dealers Paul Durand-Ruel and Theo van Gogh, and only in reference to bills he owed. No letters addressed personally to or from Cluzel are found in Degas’s correspondence. This should not be surprising: Degas’s studio was only a few blocks from Maison Cluzel at 33 rue Fontaine in Montmartre, and Degas’s paint supplier had his shop just next door to Cluzel at 31 rue Fontaine, so it seems likely that Degas and Cluzel did their business in person.

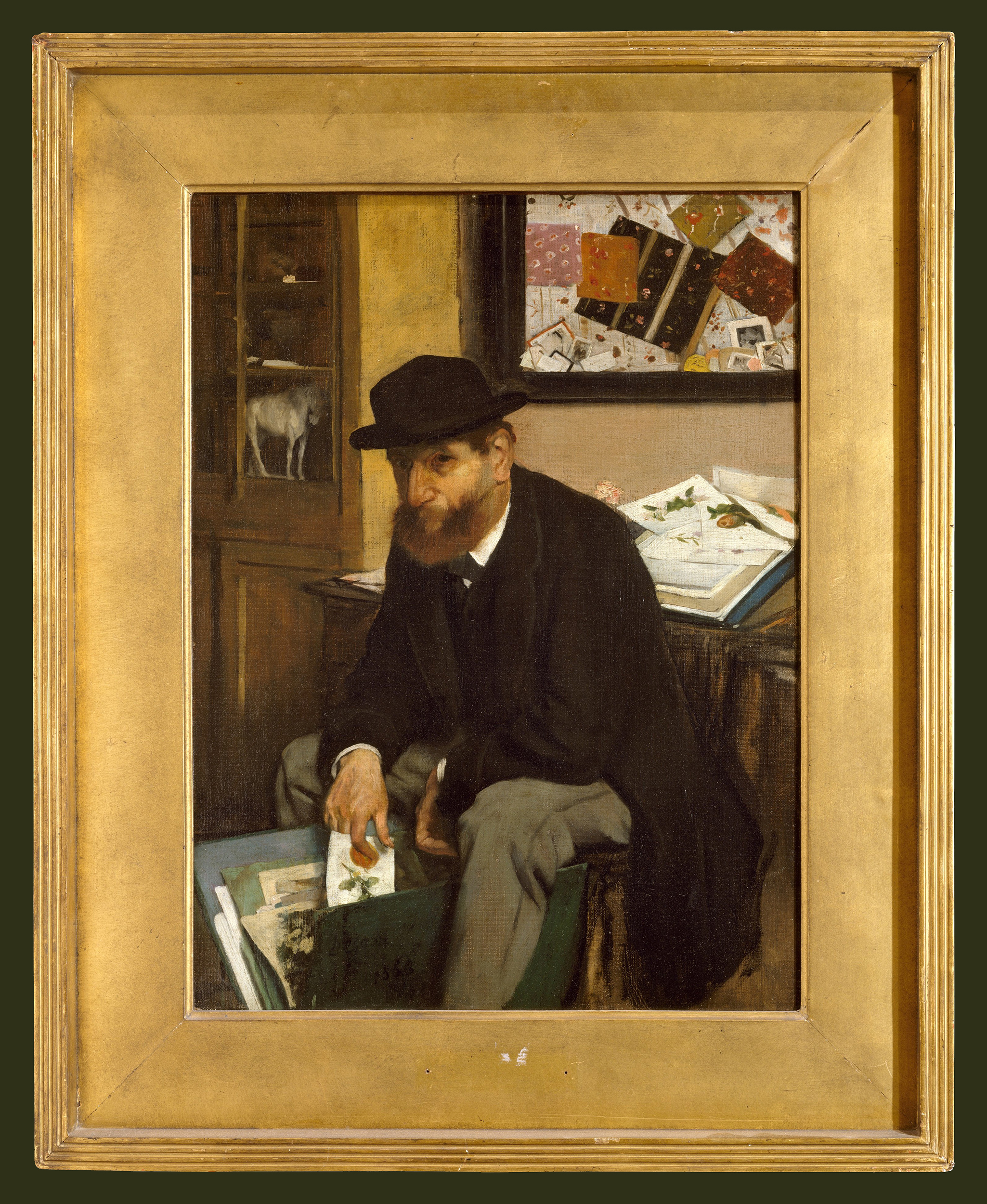

Because we lack written descriptions of their interactions, as we have for Pissarro, the impact Cluzel had on Degas’s designs remains speculative. A close look at the extant frames by Cluzel on Degas’s works, however, offers some valuable clues. We can find the label of Maison Cluzel on three of Degas’s works preserved at the Metropolitan Museum in New York (Woman with a towel, Sulking, and The collector of prints).

Degas (1834-1917), sketch from Carnet de croquis no 23, Département des Estampes, Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Degas (1834-1917), Sulking, c.1870, o/c, 32.4 x 46.4 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436162

Profile drawing taken by the author from the frame of Sulking, by Cluzel

These three are noteworthy, for while they bear resemblances to designs from Degas’s sketchbook, the finished frames exhibit much more refinement. In the case of Degas’s extreme crète de coq moulding, the extant frames in this format are much more pronounced than the closest sketch we have from Degas. It is certainly possible that Degas provided a sketch for Cluzel which is now lost. It is equally possible that Degas and Cluzel developed this shape together [14].

Evolving tastes and the rarity of the artist’s frame

Over the last 30 years, interest been mounting in the art world in joining paintings with frames of their own era. Museums are reuniting paintings with their original surrounds when possible and utilizing antiques when the original is lost. Joining a painting with an antique frame from the same period is certainly ideal, especially when you are able to locate a style of frame approved by the artist. Late 19th century Salon frames can be found, but with some exceptions these are antithetical to the intentions of the artists who were trying to distance themselves from the Salon system.

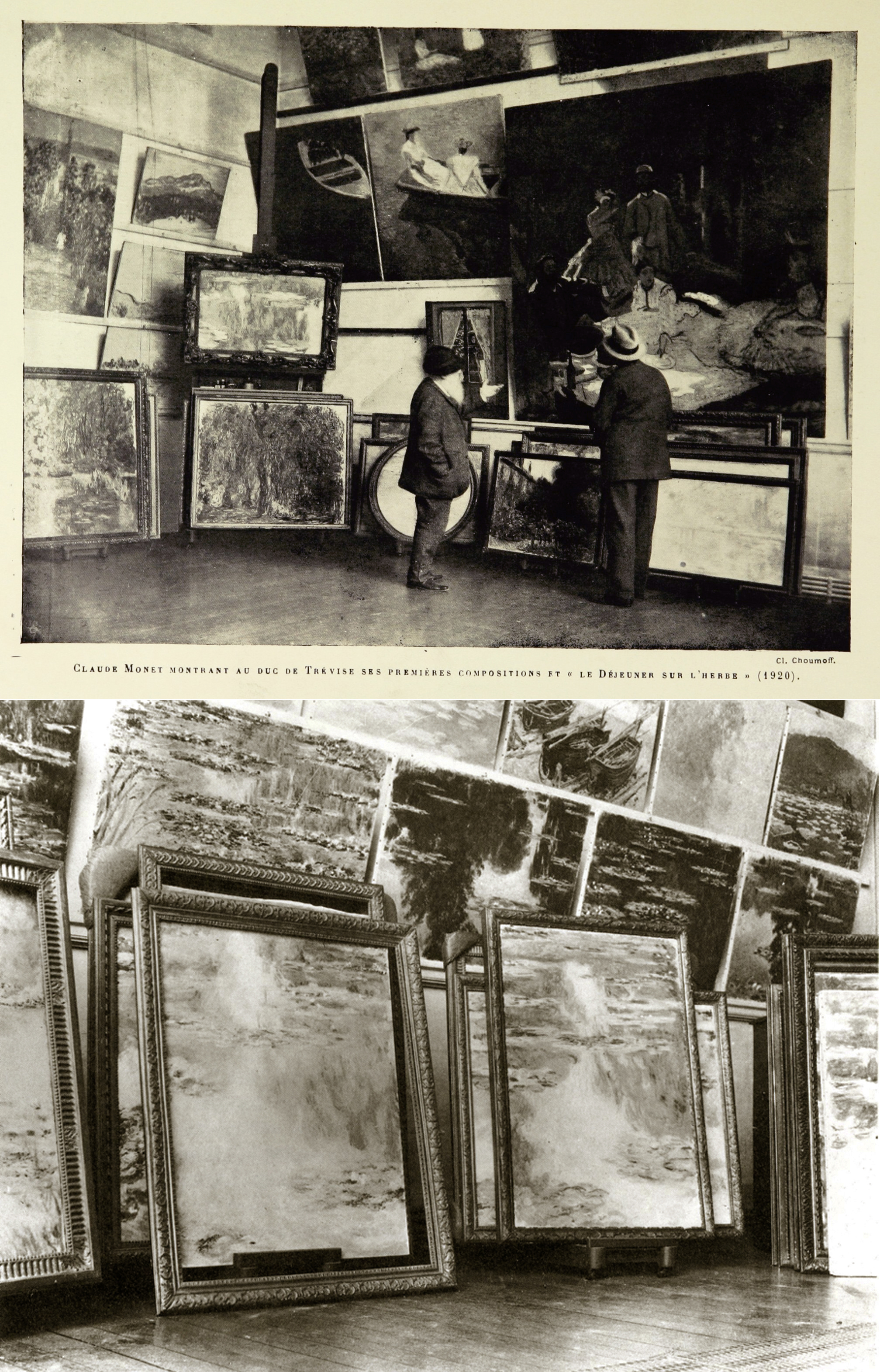

Monet’s studio: in 1920 with the duc de Trévise (top) & before 1909 exhibition (below)

Museum-goers may well wonder why some works by the avant-garde are presented in conventional frames, while others feature borders which are entirely unique. Not all artists associated with Impressionism felt compelled to use the progressive frame designs of their colleagues. Monet did not design his own frames, and was in the habit of asking his dealer to choose his frames for him [15]. In one particular piece of correspondence he expresses his fondness for antique frames [16], and photo evidence from his studio at Giverny shows his work housed in Baroque-style, Louis XIV, and Barbizon frames. Renoir shared Monet’s interest in traditional framing, proclaiming his preference for

‘…old frames carved from hardwood, where we feel the hand of the worker.’ [17]

Degas (1834-1917), Baigneuse allongée sur sol, c.1885, pastel on paper, Musée d’Orsay

Museums looking to join an avant-garde painting with a progressive model from the late 19th century may find it very difficult to locate such a frame, since they were customarily discarded over the years as paintings changed ownership, and tastes evolved. This was the fate of many of Degas’s painted frames, although Degas is known to have stipulated that his works must stay with their frames [18].The dealer Ambroise Vollard recounts that Degas even repossessed a painting in anger upon finding that one of his frames had been removed [19]. Even Degas’s crète de coq frames, which Vollard described as one of Degas’s favorites [20], have disappeared, except for the two surviving examples illustrated here (in the Metropolitan Museum, and the Musée d’Orsay, above).

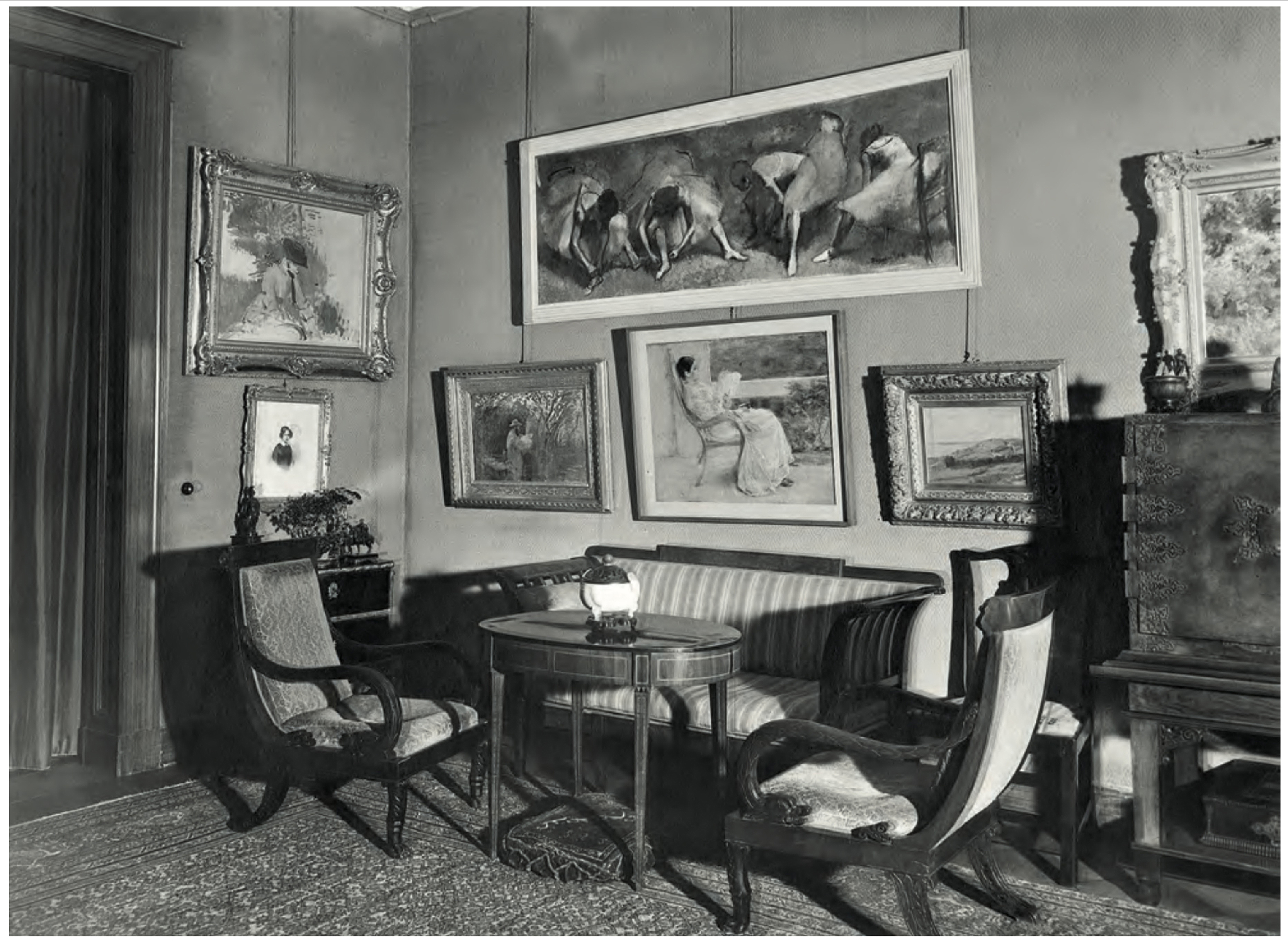

Degas (1834-1917), Frieze of dancers, c.1895, Cleveland Museum of Art, photographed in Max Liebermann’s living-room, Berlin, 1932

A photograph of Max Liebermann’s living room in Berlin, suggests that Degas’s Dancers trying on their slippers, now in the collection at the Cleveland Museum of Art, was once housed in a white crète de coq frame.

Some designs were seen as being too radical, and it should come as little surprise that a white crète de coq moulding would have stood out in many settings. Degas’s painted frames may have appeared too plain or unfinished against the gilded décor of many collectors, and dealers found it easier to sell a painting if it was housed in a conventional gold frame. We get the sense from Pissarro’s letters that he sometimes quarreled with his dealers who were upset by the lack of gilding on his frames [21].

Hugues Merle (1823-881), Portrait of Paul Durand-Ruel, 1866, o/c, 113 x 81.5 cm., in a Durand-Ruel NeoClassical-style frame, Archives Durand-Ruel

Durand-Ruel in particular favoured a gilded Louis XVI revival pattern for many works which passed through his gallery. By the 1890s dealers were able to begin selling paintings by the Impressionists more steadily, giving the artists much-needed financial security and the dealers themselves more leverage over presentation.

Yet even when a work was sold in an artist’s frame, it was common practice for collectors to reframe it in a style which harmonized with the rest of their collection. Some collectors employed what is known as a house-style for their framing, which had the effect of homogenizing the presentation of works by different artists, and at the same time impressed the stamp of ownership on the individual work.

Degas (1834-1927), Trois danseuses, 1873, o/c, 27.5 x 22.7 cm., Christie’s, 27 February 2019, Lot 24, in Camondo frame

An interesting example is the frame pattern employed by comte Isaak de Camondo which had a decorative Louis XVI-style ribbon-&-stave motif on the back edge, coupled with the more modern flat frieze of the passe partout or architrave model.

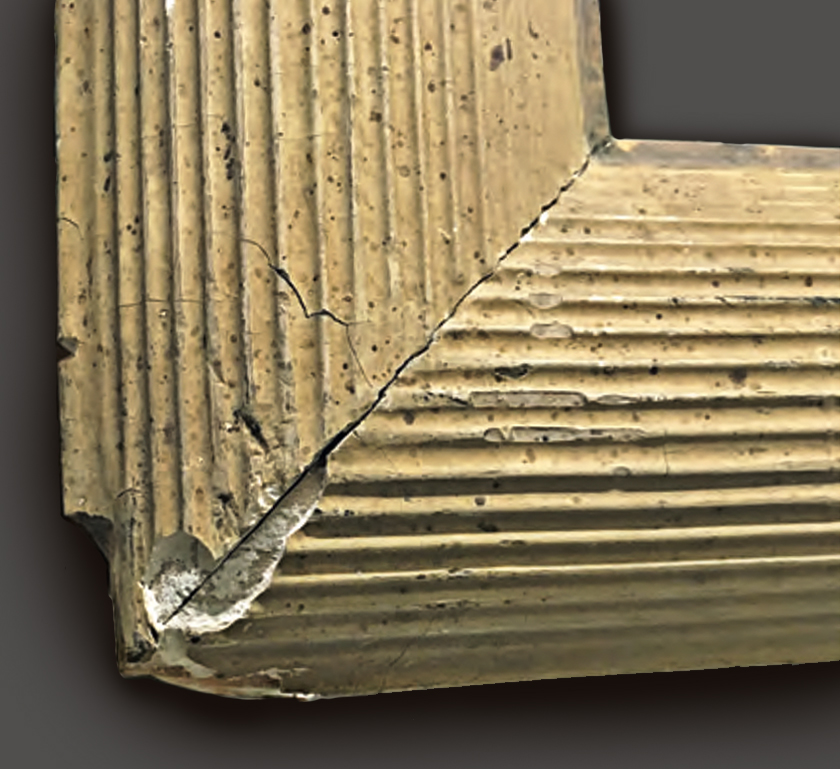

Detail of a damaged late 19th century reeded frame made with template-shaped pâte coulante, Musée d’Orsay

The disappearance of the original frames may also have something to do with the material itself. In the case of a finely modelled frame in pâte coulante, certain kinds of damage are very difficult to repair. If a section of the moulding was crushed or lost, it may have been easier for a collector or an institution simply to replace the frame rather than to try to recreate the lost section.

Method and technical insights

French pine moulding frame, coloured with burnt red oil paint, 19th century, attrib. Pierre Cluzel workshop, and details, Artcurial, Paris, 20 January 2016, Lot 419

Extant artists’ frames in pâte coulante from the late 19th century are rare and therefore seldom available for structural analysis. One exception is an extremely complicated period frame in pâte coulante attributed to Maison Cluzel (above), which was once owned by the Parisian antique frame dealer, Christophe Nobile [22]. Its shape bears some resemblance to the two crète de coq frames original to Degas’s bathers at the Metropolitan Museum and Musée d’Orsay, but the individual elements which make up the moulding are a mixture of large and small reeds, blades, and curls. The state of the frame was in disrepair when it entered Nobile’s collection, and in order to restore the frame and reinforce the joinery, he was forced to open the frame at the mitres.

Cross-section of Cluzel attrib. French pine moulding frame

This afforded him the opportunity to study the construction details of one of these extreme frames via the cross-section. The wooden carcase was assembled from rather simply-shaped slats laid over one another. The built-up layers of paste make up a large amount of the moulding, which suggests that this design might have been modified and expanded during fabrication. This rare view of the cross-section of such a unique example was illuminating in itself, but raised challenging questions regarding execution which were difficult to answer. What are the working properties of a material which is hard enough to withstand handling but not prone to shrinkage, and how efficiently could that material be built-up to this extent? The technical analysis which follows offers some explanation.

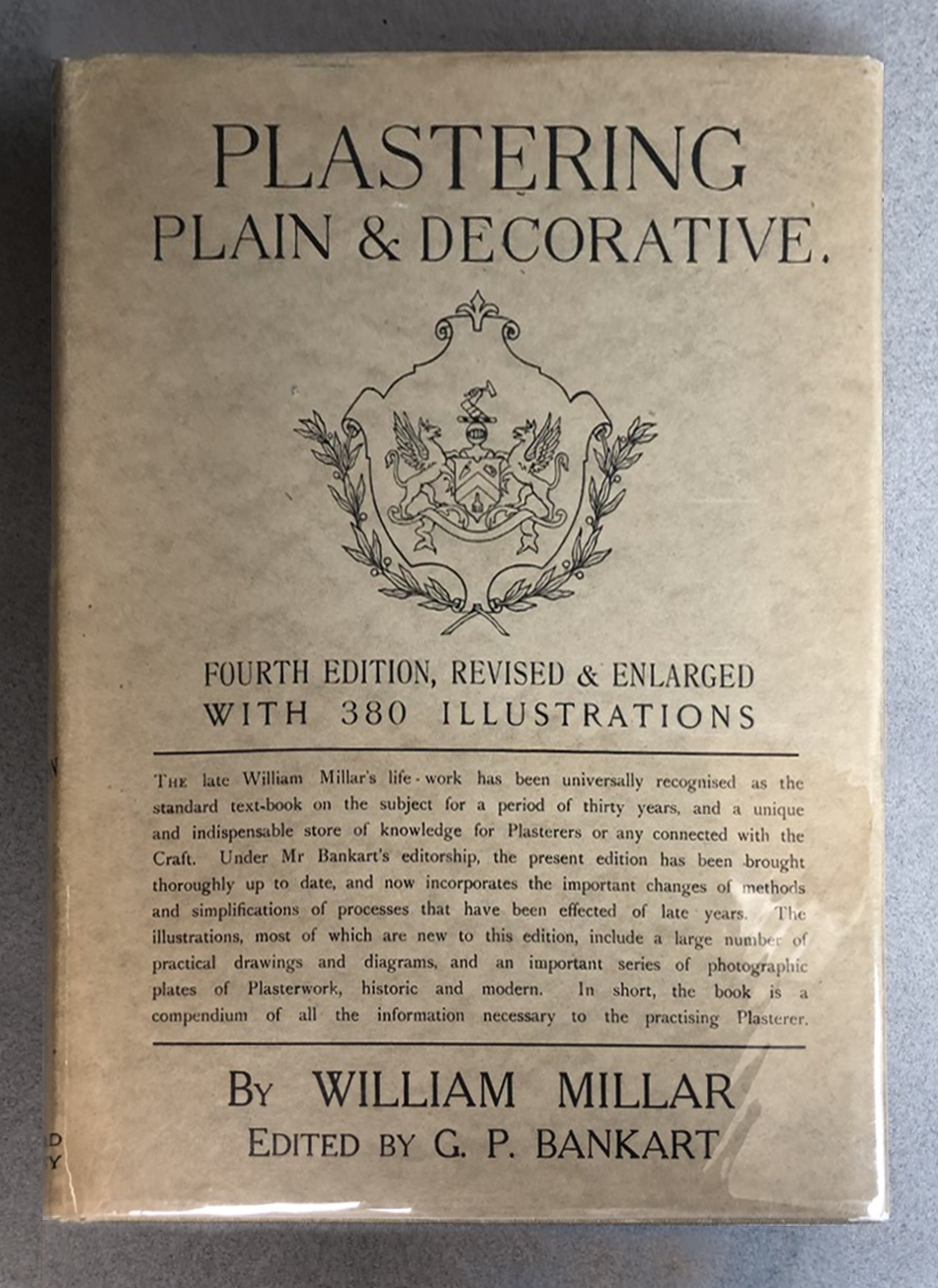

William Millar, Plastering: plain & decorative, London, 1905

The most detailed instructions for making pâte coulante appear in the 1905 edition of William Millar’s landmark treatise on architectural plaster work, Plastering, plain and decorative [23]. Millar’s recipe comprises materials found in 19th century frame shops and plaster studios alike: fine plaster, chalk (whiting), rabbit skin glue, and alum (potassium aluminum sulphate). Although the exact ratio of elements is not specified in Millar or any other treatise from the era, the basic principle is that fast-setting plaster is added to traditional gesso (chalk and rabbit skin glue) so that the artisan can build layers quickly; the plaster gives the mixture form, and the gesso gives the mixture hardness.

Through trial and error, it was apparent that the properties of the materials are sensitive to each other, and the ratios are dependent on the application. A higher ratio of glue provides added strength to the cured paste, but it is too springy to be cut properly under the template and is therefore best used for cast ornament. The guiding criterion for a recipe of pâte coulante for this study was a mixture of properties common to both traditional gesso and composition: the material must be able to accept bole for gilding and hard enough to take a fine burnish; it should not compress under the pressure from burnishing; and must be dense enough to resist scratching.

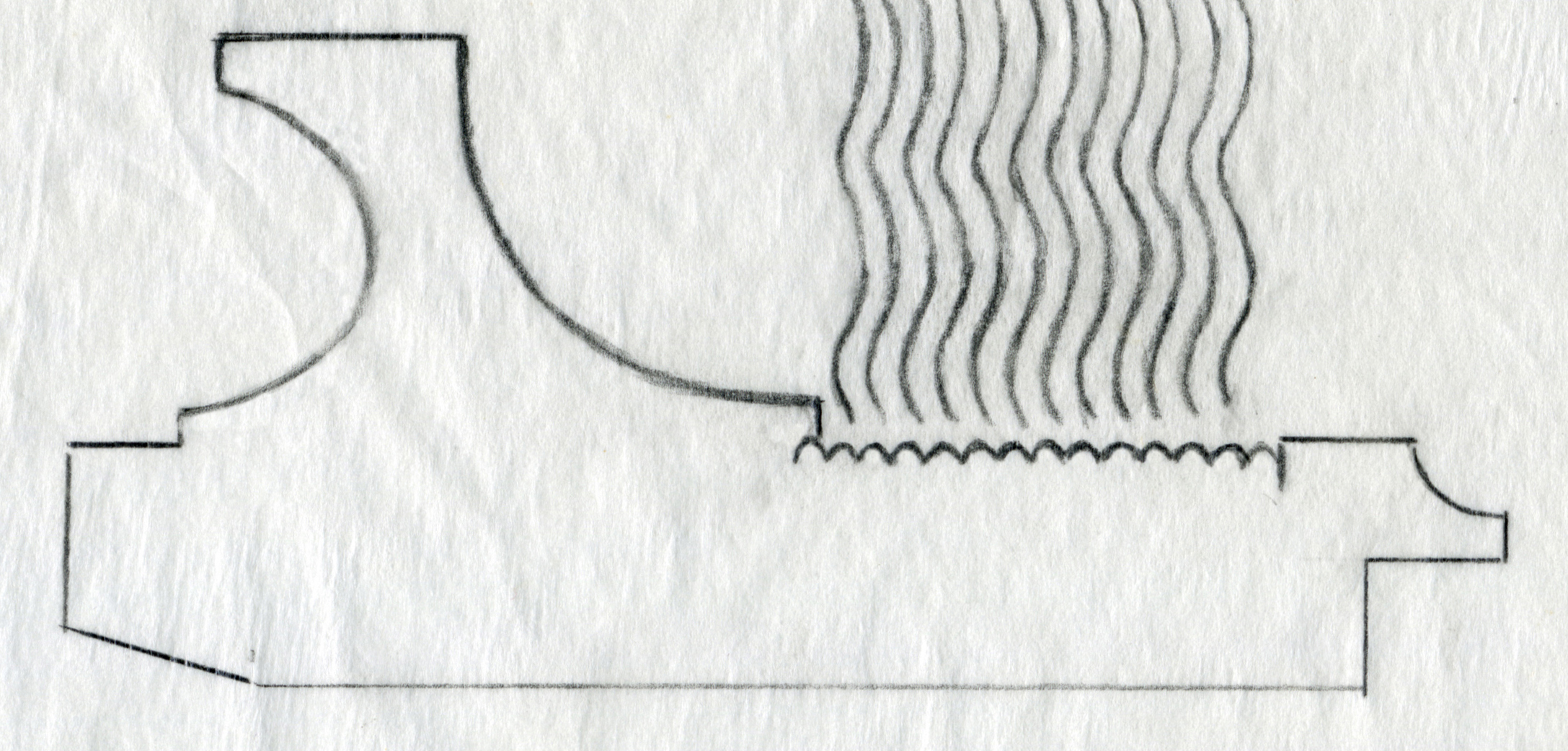

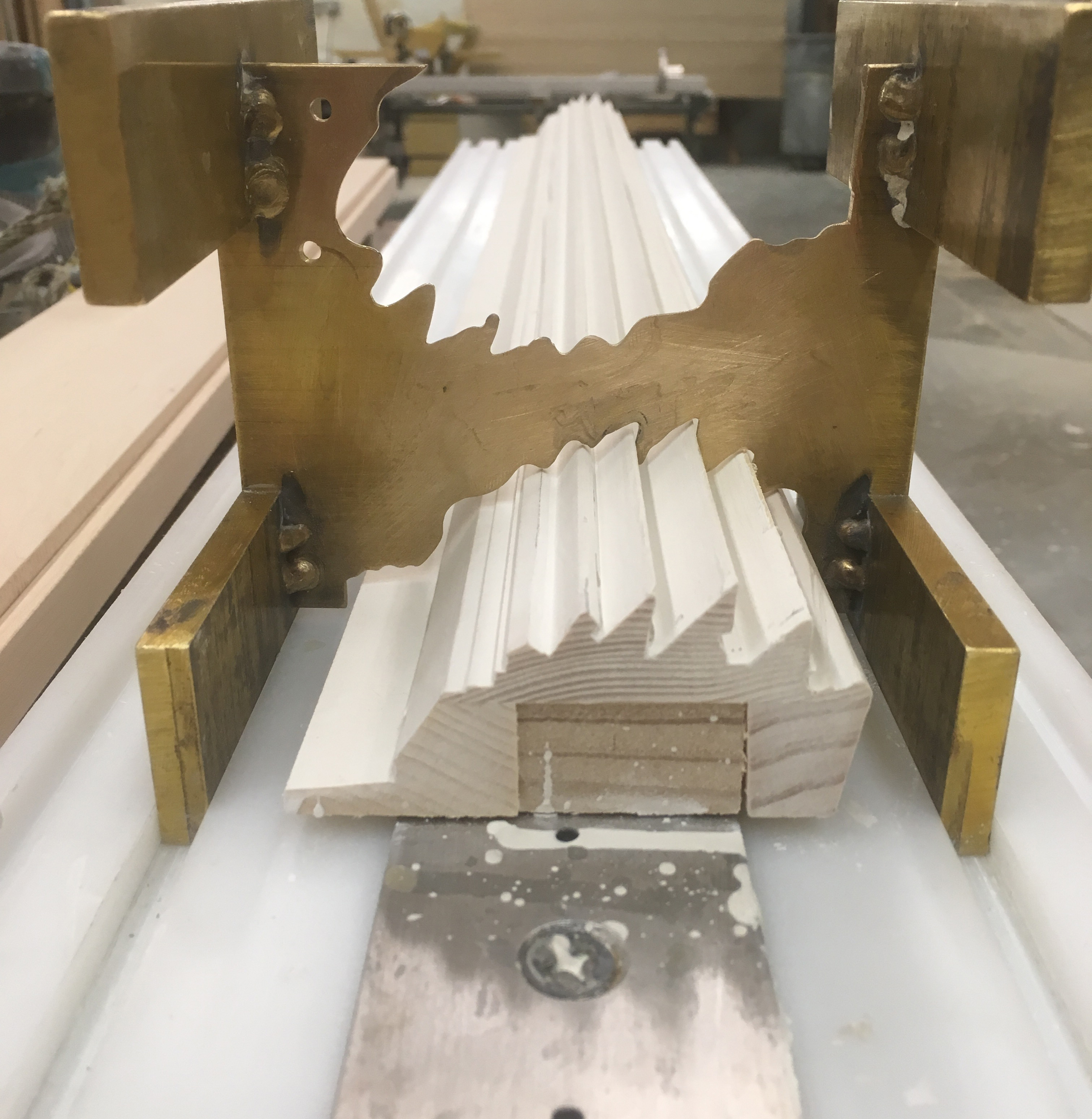

Pâte coulante, shaped by template

As mentioned in the period manual by J. Saulo above, a wooden substructure following the general shape of the finished profile is essential. A wooden interior frame, preferably hollow, will keep the weight down and provide traditional joinery options for the framemaker. The paste is heavier than the wood, and throughout the process the paste contributes moisture to the wooden base. It is therefore worth the effort to match the wooden substructure to the shape of the finished moulding as closely as possible, as above. The late 19thcentury method for keeping the wood stationary during the application of the paste remains unclear.

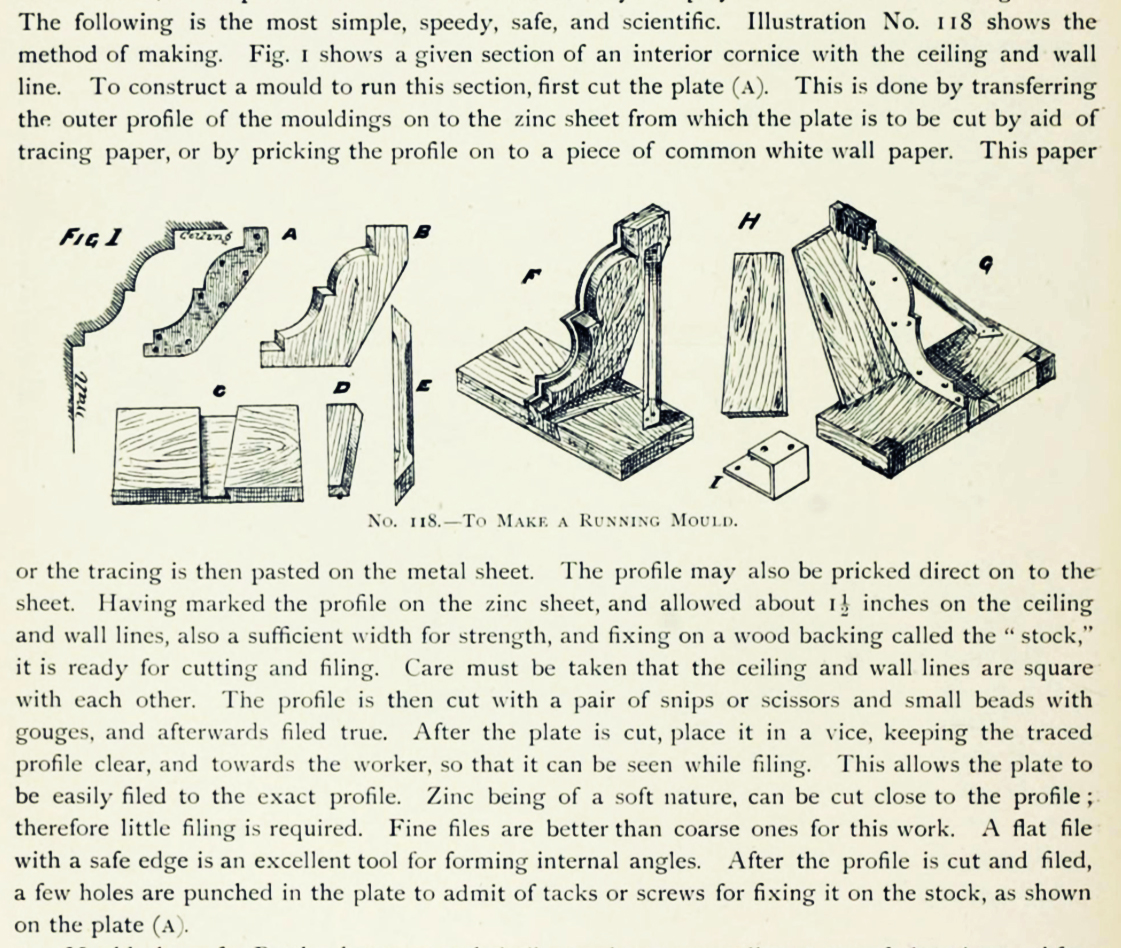

How to construct a running mould for a plaster cornice, from William Millar, Plastering plain & decorative, 1905, p. 310. Internet Archive

Given the similarities between cutting pâte coulante for frame mouldings and cutting plaster for interior mouldings, it is conceivable that framemakers were familiar with the process of fixing a metal template onto a wooden chassis with a fence [24].

The templates for shaping pâte coulante specified in the manual by J. Saulo of 1896 are made of iron. The treatise of plastering techniques by Millar of 1905 suggests thin sheet metal. No period photographs or diagrams which describe the system used by framemakers for the travelling template were found. For the purposes of this study, a track system was developed which would give the best chances for reliable results.

As in the processes for moulding plaster, pâte coulante is applied soft and run over with the template until the material can hold its shape. The maker can add fresh paste and recut as soon as the prior coat begins to stiffen, provided the track, carcase, and template are kept wet and running smoothly. The fineness of the template is very important for the efficiency of this process; if the cutting edge is very carefully smoothed then there is no need to sand the finished moulding. This must have been an immense boon for framemakers who manufactured profiles which required absolute uniformity from moulding to moulding. A more refined surface texture is achieved by switching from pâte coulante to very thin gesso for the last few passes, once the moulding is massed out, which gives the surface the ultra-smooth, polished texture found on some period examples.

The lengths of finished and well-dried mouldings are then cut and trued to 45 degrees. Performing a preliminary cut with a bandsaw, which was available in Europe at the end of the 19th century [25], and then smoothing the mitre by sanding, yields the best glueing surface. Closing the seam of the mitre takes some patience. Microscopically, pâte coulante shears much more cleanly than wood fibres on a mitre cut. Additionally, some small expansion occurs when aqueous glues are applied to wood. These factors contribute to a hairline gap on the face of the mitre, and some delicate filling is always required. The seam may require many light fills with the aqueous gesso until the mouldings are consolidated. Once the seams are mended, the frame can be treated as one would a traditional gesso frame; the surface will take bole or paint.

Degas (1834-1917), The collector of prints, 1866, o/c, 53 x 40 cm., in his ‘pipe’ moulding, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Template-cut pâte coulante mouldings can also be integrated with traditional woodwork. One fine example is the well-known ‘pipe’ moulding (or passe-partout) on Degas’s Collector of prints at the Metropolitan. The carcase of the frame is made very much like a traditional cassetta, with broad flat boards keyed from the back. The fluted moulding is glued to the face of the frame.

Degas (1834-1917), sketch for his so-called ‘pipe’ frame from Carnet de croquis no 5, Département des Estampes, Bibliothèque Nationale de France; construction details for Cluzel’s frame on The collector of prints, with template-shaped pâte coulante in light blue over two-part wooden carcase; gesso layer in white covers the rest of the profile, hiding the transition between pâte coulante and wood

Damage to the flutes reveals that the decoration is shaped in paste about 1/8 inch thick over a square wooden rail. After the moulding was mitred and glued to the frame, the whole carcase was gesso’d in the traditional manner.

Because so many of the original models have been lost, research on artists’ frames is challenging. Nevertheless, period treatises on construction practices, artists’ correspondence, and the extant models we do have reveal an intricate link between process and design. The multitude of factors which contributed to the frame inventions of the late 19th century offer a critical insight into the artists’ working practices, and illuminate not only the paintings from that era, but also the economic climate, prevailing tastes in architecture and interior design, and the proliferation of aesthetic ideas and processes.

******************************

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the many colleagues who offered their knowledge and support in the research for this paper. For their generosity I would especially like to thank Cynthia Moyer, Associate Conservator at the Metropolitan Museum, and Christophe Nobile, owner of Maison Samson. For offering their technical expertise I would like to thank Tracy Gill, Simeon Lagodich, and Yozo Suzuki of Gill & Lagodich Fine Period Frames, Ross Caudill, Chief Fabricator at the Guggenheim Museum, and Jed Bark of Bark Frameworks. I would also like to thank David Horowitz, Assistant Curator at the Guggenheim Museum for his close read and valuable insights into an early version of this work.

Peter Mallo is an artist, scholar, part-time member of the Faculty at Parsons School of Design, director of learning & development and former chief of frame design and production at Guggenheim, New York.

******************************

Bibliography

Bailly-Herzberg, J, Lettres de Camille Pissarro à son fils Lucien, vol. 2, Presses Universitaires de France, 1991

Cahn, Isabelle, Cadres de peintres, Hermann – Réunion Des Musées Nationaux, 1989

Cahn, Isabelle, ‘Degas’s frames’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 131, no 1033, April 1989 pp. 289-293

Clark, Timothy James, The painting of modern life, Princeton University Press, 1999

Degas’s letters, ed. Marcel Guérin, transl. Marguerite Kay, Cassirer, 1947

Destremau, Frédéric, ‘Pierre Cluzel (1850-1894) encadreur de Redon, Pissarro, Degas, Lautrec, Anquetin, Gauguin’, Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art Français, 1995, pp. 239-47

Doughty, O., & Wahl, J.R., Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Clarendon Press, 1965

Durand-Ruel, Flavie, Paul Durand-Ruel: Memoir of the first Impressionist art dealer, Flammarion, 1994

Easton, Elizabeth, & Bark, Jared, ‘Pictures properly framed’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 150, no 1266, September 2008, pp. 603-11

Grimm, Claus, Alte Bilderrahmen, 1978, transl. as The book of picture frames, 1981; see Internet Archive

Havemeyer, Louisine, Sixteen to sixty: Memoirs of a collector, Ursus 1993

Heydenryk, Henry, The art and history of frames, Heineman, 1963; see Internet Archive

House, John, Monet: Nature into art, Yale University Press, 1986

Horowitz, Ira, ‘Whistler’s frames’, Art Journal, vol. 39, no 2, winter 1979-80, pp.124-31

In Perfect Harmony: Picture + Frame 1850-1920, ed. Eva Mendgen, Waanders Publishers, 1995

Kendall, Richard, Degas by himself, Little Brown & Company, 1987

Leroy, Leonard, ‘L’exposition des impressionistes’, Le Charivari, 25 April 1874

Millar, William, Plastering: plain and decorative, Batsford, 1899; see Internet Archive

Newbery, Timothy, Frames in the Robert Lehman Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007

Payne, John, Framing the 19th century: picture frames 1837-1935, Images Publishing Group, 2007

Pearce, William, Painting and decorating, Charles Griffon, 1898

Reff, Theodore, Degas: The artist’s mind, Harvard University Press, 1987

Renoir, Jean, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, mon père, Gallimard, 1981

Rewald, John, Camile Pissarro: Lettres à son fils Lucien, Peregrine Smith, Inc., 1981; see Internet Archive

Rewald. John, The history of Impressionism, Museum of Modern Art, 1961

Saulo, J, & the Chevalier de Saint-Victor, Nouveau manuel complet du fabricant de cadres…, 1921 ed., see: Watson Library Digital Editions, Metropolitan Museum

Simon, Jacob, The art of the picture frame, The National Portrait Gallery, 1996

Soros, Susan Weber, & Arbuthnott, Catherine, Thomas Jeckyll: architect and designer, 1827-1881, Yale University Press, 2003

Thornton, J, ‘The history and technology of waveform mouldings’, Wooden Artifacts Guild Postprints, 2002

Vollard, Ambroise, Degas: an intimate portrait, transl. Randolph Weaver, Crown, 1937; see Internet Archive

Vollard, Ambroise, Recollections of a picture dealer, transl. Violet Macdonald, Little Brown and Company, 1936: see Internet Archive

Ward, Martha, ‘Impressionist installations and private exhibitions’, The Art Bulletin, vol. LXXIII, no 4, December 1991, pp. 599-622

Wildenstein, Daniel, Claude Monet: Biographe et catalogue raisonné, vol 4, La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1974

******************************

[1] Louis Leroy, ‘L’exposition des impressionistes’, Le Charivari, 25 April 1874

[2] Havemeyer, 1993, p. 250

[3] J.M. Whistler, Letter to George Aloysius Lucas, 18 January 1873, preserved at the Walters Art Gallery Library, Baltimore

[4] The task of tracking design trends is complicated by the competitive attitude which developed in the 1880s between Whistler in London and some of the Impressionists in Paris. With regard to intimately choreographed spaces, both sides claimed ownership. Writing to his son in London in 1883, Pissarro laments that the Impressionists are not receiving their due credit:

‘How I regret not to have seen the Whistler show… he is even a bit too pretentious for me, aside from this I should say that for the room white and yellow is a charming combination. The fact is that we ourselves made the first experiments with colours… But we poor little rejected painters lack the means to carry out our concepts of decoration’.

(John Rewald, 1961, pp. 22-3)

It’s also important to note that some frame styles which have been named after certain artists, like Whistler, may not be entirely of their invention. Known for his keen sense of interior design, Whistler was initially influenced by the design trends begun by the Pre-Raphaelites, and by architects like Thomas Jeckyll (Soros and Arbuthnott, 2003, pp. 190-97) with whom he collaborated on the Peacock room. In terms of frame design, Whistler does seem to be the most vital conduit for ideas between Paris and London. He lived and worked in Paris in the early stages of his career, and even after settling in London, he is known to have had some of his frame designs executed in Paris (Isabelle Cahn, 1989, p. 63)

[5] Degas, ‘To the jury of the 1870 Salon’, Paris Journal, 12 April 1870; reprinted in Richard Kendall, 1987, pp. 99-100

[6] For an excellent summary of the shift to mass market manufacturing, see Clark, 1999, pp. 46-52

[7] Millar: op. cit. note 13, p. 1-24, 296-323

[8] Thornton, 2002

[9] ‘Quand on commença à faire des cadres en pâte, le profil était entièrement fait de bois, jusque dans ses menus details… Ce procédé était certainement d’un emploi très long et fort onéreux, mais le produit était, par contre, aussi beaucoup plus solide. Avec le progrès s’est manifestée la nécessité de produire à bon marché ; on a alors simplifié ce travail en se contentant d’indiquer seulement, dans le bois, les sinuosités générales du profil. Pour obtenir les détails, on a fait des gabarits en fer reproduisant en à-jour les moulures exactes du profil… C’est, comme on voit, certainement très pratique et peu dispendieux ; le seul inconvénient, mais qui a son importanse, c’est que le produit est beaucoup moins solide que ce que donnait l’ancien procédé.’

Saulo and St-Victor, 1896, pp. 12,13

[10] Bailly-Herzberg, 1991, pp 481, 544

[11] Ibid., note 18, pp. 158, 236

[12] Ibid., note 18, p. 435

[13] Paris, National Archives of France, Minutier central des Notaires CXX-976 (unpublished): ‘Inventaire après la décès de M. Cluzel’, 1896

[14] Christophe Nobile, a framemaker, restorer, and owner of Maison Samson in Paris, who has closely studied the crète de coq frame preserved at the Musée d’Orsay, favors the hypothesis of collaboration:

‘The picture framer Pierre Cluzel, who closely collaborated on the creation of the crète de coq model, was certainly a chef d’orchestre who oversaw the different inventions. These mouldings were built up like sculptures and so it is unsurprising that from the sketchbook to the finished product there are evolutions’.

C. Nobile, personal interview, 25 November 2018

[15] House, 1986, p. 180, 181, 215

[16] Letter to À.O. Maus dated 18 January 1897. Monet is preparing to send three paintings of the Rouen Cathedral to Libre Esthétique and provides instructions for the handling of his old frames:

‘I shall be very grateful to you for giving instructions to take care of the frames, they are antique bordures, of which I am especially fond.’

Quoted in Wildenstein, 1974, p. 292

[17] Renoir, 1981, p. 298

‘Looking at a pastel by Degas, a stout woman bathing in a chamber, Monet said he valued Degas’s drawing only, and it was a common trick of his to make the frame assist and complete the picture.… The picture was sold to Monet with the stipulation from Degas that the frame must be kept.’

Diary of Theodore Robinson (unpublished), vol. 1, 7/8 July 1892, p. 34, New York, Frick Art Reference Library

[19] Vollard, 1937, pp. 65, 66

[20] Ibid., note 30, p. 65

[21] Rewald, op. cit. note 8, pp 23, 102; see also Bailly-Herzberg, op. cit. note 17, p. 160

‘I’ve had the opportunity to have a close examination of a very few (about three different models) of those period frames and I would say these prototype frames were fabricated dans les règles de l’art by experienced professionals.’

Nobile, op. cit., note 22

[23] Although Millar is working in London, he uses the French name for this material, which was called by other names, including ‘Alabastine’, (Pearce, 1898, pp. 265-70) and ‘economic paste frames’ (Cahn, op. cit., note 4 pp. 10, 15); Millar, 1905, p. 403

[24] Due to the strong connection with architectural plasterwork, my early suspicion at the outset of this research was that framemakers might have contracted their orders for paste frames out to professionals in the plaster mouldings trade; but, based on the account of J. Saulo, it seems equally likely that templated paste frames were manufactured in-house by framemakers

[25] The concept for the bandsaw dates to the beginning of the 19th century, but the welding technology of the time was inferior to the rigors of usage. In 1846 Anne Paulin Crepin of France applied for, and was granted, a patent for a new welding technique which allowed the blades to withstand the stress of cutting and flexing at high speeds. She sold the patent to A. Perin & Company of Paris, who brought modern bandsaws into the mainstream