Charles Henry Savory: The Practical Carver and Gilder

The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide, and picture frame makers’ companion was a handbook for modest commercial and amateur craftsmen which enjoyed unexpected popularity in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, running to five editions between c.1874 and c.1877 [1], and continuing to be reprinted until at least 1900. But who was the author?

The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide, and picture frame makers’ companion, ‘By a Practical Hand’, cover of the fourth edition, c.1877: published in London by Kent & Co., and in Cirencester by C.H. Savory

The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide, and picture frame makers’ companion, ‘By a Practical Hand’, cover of the fourth edition, c.1877: published in London by Kent & Co., and in Cirencester by C.H. Savory

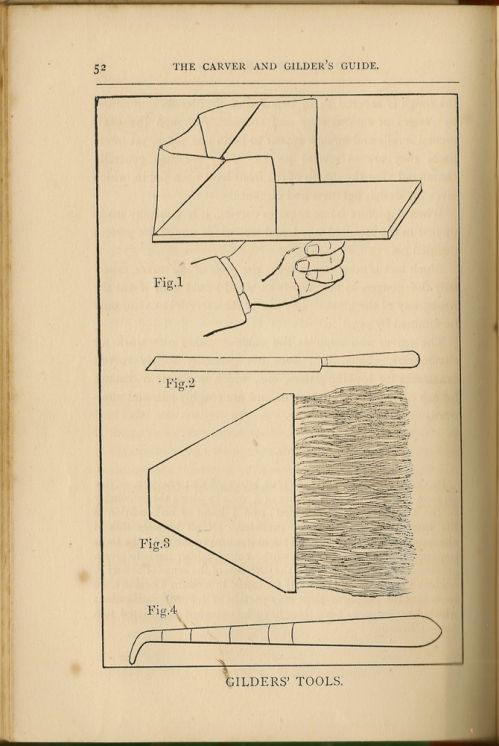

Many people who are interested in the history of picture frames will have come across this book; it pops up in bibliographies, it graces countless libraries, and copies of it are for sale ubiquitously on the internet. It gives a fascinating picture of practices, recipes and fashions at what might be called the High Street end of the market during the last quarter of the 19th century. It doesn’t do, perhaps, precisely what it says on the can – there isn’t any real information on carving; but what it does cover can be summarized from the contents pages: Mouldings; Picture and Looking-glass Frames; Plate Glass; Silvering Plate Glass (I don’t think that you’re expected to try this at home); Composition Ornaments; Gilder’s Tools; Preparations Used in Gilding; Gilding; Interior and Exterior Gilding; Cleaning and Restoration of Oil Paintings; Picture Frames and Their Manufacture (5 pages); Mitreing Picture Frames; Mounting Pictures; Fitting-up and Hanging Pictures; Mount Cutting; French Polishing, Varnishing and Staining; Receipts and General Information.

The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide…, title page of the fourth edition

The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide…, title page of the fourth edition

One edition or earlier, slender version seems to have been called The Amateur Picture Frame Maker’s Instruction Book, and sold for sixpence. The fourth edition of The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide had 201 pages, covering all the various chapters indicated, and cost ‘Two Shillings and Sixpence’ (12.5 pence) – an increase of 500% over three or four years. It evidently fulfilled a need: a lacuna of instruction in the growing market for cheaper, mass-produced frames, affordable by many more people of all sorts of conditions and classes, which reflected the similarly vibrant market for economic versions of other ‘luxury’ goods during the 19th century. As the writer states in his preface,

‘If any comprehensive book on the subjects treated on had been published, this volume would not have been written, but it is intended to supply a want, and a measure of success is anticipated in consequence.

If I get appreciative readers who can say in the words of Tennyson-

“Well hast thou done, – In setting round thy first experiment With royal framework of wrought gold”,

the effort will not have been in vain.’

The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide…, advertisement page of the fourth edition

For a while, this book was categorized as anonymous in twentieth century bibliographies of picture framing history, or under its author’s nom de plume, ‘A Practical Hand’, but later it was given to its publisher and provincial printer, C.H. Savory of Cirencester – probably because in later editions, he advertised in the back pages a patent kit – ‘The Amateur Picture Frame Maker’s Tool Chest’ – available from himself, under the guise of ‘Carver & Gilder’ rather than as the proprietor of the Steam Press, Cirencester, which printed the output of ‘A Practical Hand’. So who was this C. H. Savory, with his two distinct trades and his flourishing bestseller? Some of his history is traceable online, and some of it has been made available in this article through the kindness of Savory’s great-great-grandson.

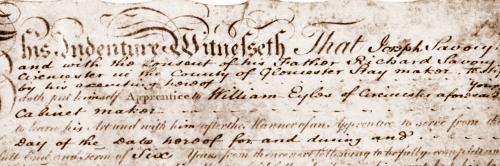

Extract from the indenture of Joseph Savory, 1808. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

Savory may have descended from Huguenot ancestors, although his nearer forebears were yeomen farmers in Gloucestershire [2]. His father, Joseph (1794-1866) became a cabinetmaker in Cirencester: his indenture as an apprentice survives, showing that Joseph’s father, Richard, was a staymaker, and that he paid £10 to William Eyles of Cirencester for a six-years’ apprenticeship for his son. By 1808, when this document was drawn up, apprenticeships were beginning to be abandoned for a more informal arrangement of seven years’ training, which avoided the stamp duty imposed on an indenture, but Cirencester must have been far enough from London and the South for this traditional entrance to a trade to be the norm – as it was still in Bristol, for instance, in the late 18th century [3]. The rules of apprenticeship reached back to the Statute of Artificers, passed in 1563, and the sections governing them were only repealed in 1814; apprenticeships continued to form an appreciably important method of training in the skills of various trades until the mid-19th century.

The price Richard Savory paid for his son to become a cabinetmaker is just below the median cost of £11 in the late 18th century [4]. Averages were inflated by the greater cost for these places paid in London and Bristol, and the higher prices of apprenticeships in e.g the law, so £10 was probably slightly above the average for a provincial town, and indicates that William Eyles was a craftsman of good standing who could offer valuable instruction. As an investment it obviously paid off; the long hours expected of an apprentice over six years produced a level of craftsmanship which could comfortably maintain a man and his family, all being well.

I.G Green, Portrait of Joseph Savory, 1833. Courtesy of Richard Savory.

By 1833, at the age of 39, Joseph was married and had a five year-old son, Charles Henry; in that year he had small portraits painted of himself, his wife Mary Ann, and Charles, looking prosperous, flourishing, and well turned-out.

I.G Green, Portrait of Charles Henry Savory, aged five, 1833. Courtesy of Richard Savory.

I.G Green, Portrait of Charles Henry Savory, aged five, 1833. Courtesy of Richard Savory.

Nine years later, in 1842, Charles was apprenticed in his turn, this time to a printer, Henry Smith of Cirencester. His term was seven years, and the cost to Joseph Savory was £15. It’s interesting that there should have been such a variation in the trades followed by these three generations; a route from farming stock, through a staymaker and cabinetmaker to a printer, argues that there was little room for businesses in a town the size of Cirencester to admit more than one master craftsman and his apprentice, and that the sons of the house had to move on, into whatever trade might offer.

Indenture of Charles Henry Savory, 1842. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

Indenture of Charles Henry Savory, 1842. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

Charles Savory must have been as thoroughly inducted into his particular business as his father had been. According to the terms of the indenture, he was ‘to be in his Master’s service from six o’clock in the morning till nine o’clock at night from Lady Day to Michaelmas, and as soon as it is light in the morning till nine o’clock at night from Michaelmas to Lady Day, except half an hour for breakfast, and one hour for dinner and half an hour for tea (except on Sundays)…’ He was to receive one shilling a week during the first five years, £10 at the end of the sixth year, and £15 at the end of the seventh. Thus he emerged from his novitiate aged twenty-one, with at least £15 to start up his own business wherever he could, or to enter as a skilled journeyman into another printing workshop.

The next we hear of him is in the 1851 census, when at the age of twenty-three he is a printer and compositor in Lincolnshire: driven across the width of the country to seek employment in his trade. He returned to Cirencester some unknown time after this census return, and seems to have occupied premises in Coxwell Street to begin with, at the ‘General Printing and Ruling Office’.

Charles Savory with his wife Mary (née Beck), and his eldest child, 1858. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

By 1858, aged thirty, he had married Mary Beck of Pewsey, Wiltshire, and had a child of his own (Mary Elizabeth Beck Savory); he was evidently prospering, and like his father, Joseph, had his young family recorded – this time by the still fairly avant-garde process of photography [5]. He moved further into the centre of the town, to St John Street (previously, and latterly again, Black Jack Street; Slater’s Directory of Gloucestershire shows that he was in Black Jack Street in 1859), where he operated as ‘Printer, Stationer, Bookseller, Bookbinder’, and, after twelve years in business, installed ‘The Wharfdale Patent Cylinder Printing Machine’.

No 2 St John Street (now no 6 Black Jack Street), Cirencester

No 2 St John Street (now no 6 Black Jack Street), Cirencester

Savory was evidently interested in technological advances; he saw how new crafts such as photography might be combined with his own skills in printing, since the business he began in Cirencester grew to include fine art prints and postcards, as well as illustrated books, and one of his sons became a professional photographer. Perhaps the advent of photography also spurred the combination of his printing business with the framing workshop on the same premises, so that everything could be executed in-house. There is no evidence that he learnt in any formal way how to produce picture frames; he may have referred to himself as a ‘Carver and Gilder’ in his book, but almost no carving is involved in any of its pages – instead, it is a manual which concentrates on using other new processes to produce its results, as we can see in the chapter entitled, ‘Mouldings’:

‘There was a time in the history of the trade when the carver and gilder who had an order for a frame, had either to make, or get made, the pattern moulding required; but with an increased population, and higher intelligence, a taste for the fine arts has become more popular, and consequently the carver, gilder, and picture frame maker has been patronized to a much greater extent, especially since the introduction of the beautiful art of photography. Within the last quarter of a century mouldings manufactories have sprung up in London, and in some of the principal towns in England; in such demand have been picture frame and other mouldings, that the engineer has applied his knowledge for a more rapid production, and has produced a machine that, by the aid of steam power, will turn out an enormous amount of work.’

Hyman Morell, trade catalogue from 1910, republished in facsimile by Dover Books as Victorian Wooden Molding and Frame Designs, 1992; p.20

Savory gives a couple of paragraphs to methods of copying ornamental mouldings by hand-carving, using different planes; but it is obvious that these would have been fairly primitive patterns, and that the main thrust of his activity relied on purchasing ready-made lengths of mouldings – turned out by machine-driven lathes, or embossed in soft woods, or covered in applied compo decoration. The ‘four classes of Mouldings’ which he discusses are, first, lengths of plain wood with various profiles; second, ‘Mouldings in the White’, or the same lengths ‘covered with whitening ready for the gilder’; third, ‘German Mouldings’; and lastly, ‘Veneered Mouldings’.

‘German Mouldings…are used for common work, and for those whose means will not allow them to order gold frames’.

They are one step further on from the whitened mouldings, in that they have been whitened and

‘then covered with silver leaf, after which a lacquer is spread over them, giving them a gold colour…They are washable’.

Savory doesn’t have a very good opinion of these imported mouldings (‘usually made with very common wood’); instead, his book points the reader in the direction of ‘Geo. Rees’ mouldings…A Complete List of Mouldings with Designs and Price Lists of Mounts, Ovals, &c., &c., post free for 2 stamps’, and he also carries an advert for ‘George Rees, Savoy House, 115, Strand, and 41, 42 & 43, Russell Street, Covent Garden’.

Rees’s lists of mouldings (in which the profiles and decorations would have been described briefly, but probably not illustrated) were transient records which have disappeared; it was not until engraved drawings of the decorated profiles were added to these catalogues that they began to survive, so that the ones we still have tend to date from the later 19th or the early 20th century. An example is Hyman Morell’s 50th anniversary catalogue, published in 1910 (above), and now republished in facsimile.

Ashworth, Kirk & Co Ltd, Nottingham, illustration from original catalogue, first quarter of 20th century

Another example is Ashworth Kirk’s catalogue (c.1920s?), which demonstrates how sophisticated these books became in the 20th century. When pre-cut and ready-ornamented mouldings of such elaboration were available for the provincial workshop to buy ‘in twelve-feet lengths’ (as Savory points out), the skills the framemaker required no longer included carving to any extent; just the ability to assemble the frame rapidly – but then, of course, usually to gild it.

The gilding stage seems to be where Savory’s practical skills came in. He takes around 40 pages to explain the ins and outs of gilding; it is by far the longest section in the book, and its elaboration indicates that he has been speaking from experience:

‘A piece of parchment…is nailed half way round the [gilder’s cushion], and is meant to keep the gold leaf from flying off, as the least disturbance of the atmosphere is enough to send the gold flying… The gilder…carefully takes up a leaf of gold, and dexterously brings the metal to the front of the cushion, when with a slight puff of wind from his mouth on to the centre of the leaf, it is made to lie perfectly flat.’

He had been apprenticed at the age of fourteen, when he had effectively left home for seven years; however, living with a cabinetmaker for all of his childhood, he may very probably have been taught by his father how to gild, and have joined in with the workshop activities, parcel-gilding details on furniture, boxes and cabinets, and even perhaps the odd frame. Children were drafted into work at an early age during the 19th century; this was a matter of course, and – if they could help with a family business – they very frequently did so.

The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide…, ‘Gilder’s tools’, p.52

The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide…, ‘Gilder’s tools’, p.52

This theory is given weight by Savory himself; the chapter on the actual task of gilding (after the chapters on tools and preparations) begins:

‘If there is any knowledge fully in our possession, it is certainly that which comes to us by experience… There may be objections raised as to the following methods, but the rules laid down are from practical knowledge, and have been followed thousands of times and produced capital work… It is likely some of the cheap gilding executed in London and other large places may not have the amount of work bestowed upon it as is recommended in the following pages, but our object is to lead those seeking information in a path that will crown their efforts with success.’

These may well be the sentiments of a man who is aware of having not been apprenticed in the regular way of his youth to a carver and gilder, and who may feel that his instructions are therefore open to the criticism of professionals, but who has equally been taught the skill of gilding by an expert, and has often practised it. This would also explain the emphasis on practice: The Practical Carver and Gilder’s Guide…, ‘By a Practical Hand’.

It may also explain why he drops into his book all sorts of references – quotations from poems, Shakespeare and the Bible, and nods to examples of decorative work in various locations:

‘The ancient and classic cities of old attest by their ruins the antiquity of the art of carving. Capitals, columns, vases, and friezes show, as the poet Cowper wrote, that they did “Not forget the carving and the gilding”…’

…or, on double gilding:

‘That work of this class is superior there is no doubt, and that it was thought so in the time of Shakespeare may be inferred from the speech of Fabian, in Twelfth Night, who says – “The double gilt of this opportunity you let time wash off”.’

He wrote the first version of his book when he was around forty-six; at that point, according to the census taken three years earlier, in 1871, he was supporting not only his wife, Mary, and three of his children (Mary, 13; Charles, 5; and Frederick Mortimer, 3), but his mother-in-law, his sister-in-law, and his niece and his nephew (6 and 2), with the help of one live-in seventeen year-old servant. Two other children (Ernest Wyman, 9, and Ada, 7) were probably away at school. He owned an apparently successful printing press, having invested a few years before in his Wharfdale patent cylinder printing machine, and was running a framemaking and gilding business on the side.

However, with five children and other dependents, extra money must always have been welcome, and perhaps – since he was already publishing books by other authors [6] – he started writing himself, in an effort to earn a little more for the maintenance of his large household. His own books (as far as anonymous works can be attributed) include The Paper Hanger, Painter, Grainer, and Decorator’s Assistant: containing full information as to the best methods practised in paper hanging, panelling, room decoration, and recipes, ‘By a Decorator’, 1878 (?), and also Life and anecdotes of Jemmy Wood, the eccentric banker, merchant and draper, of Gloucester. Also an account of the remarkable trial with reference to his will…, 1883 [7]. None of them seems to have had the success of The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide…, with its multiple editions, but this one book may have helped Savory to survive.

Receipt for framing a picture, signed by Ernest W. Savory, 1879. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory.

By the time of the next census, in 1881, his eldest son, Ernest Wyman Savory, is working in the family business as ‘Assistant (Bookseller)’, and Savory himself appears as a ‘Printer & Bookseller’’ He is head of a family which now includes his wife, his children Ernest (19), Ada (17 and still a ‘Scholar’) and Charles (14 and also a ‘Scholar’), a boarder, and one eighteen year-old servant. His eldest daughter, Mary Elizabeth, is already married to Thomas Bullock, and is in possession of a two year-old son; his other son, Frederick Mortimer, is 12 or 13, and must have been away at school. The presence of a boarder argues that finances may still have needed propping up, but that Ada at least had not been removed from school as soon as she reached fourteen. There is no mention in the census of the carving & gilding business, but it was obviously continuing (see the receipt, above), and C. H. Savory must have passed on his skills to his son, Ernest. Sadly, he didn’t survive to see what Ernest made of them. Two years later, at the early age of 55, Charles died – possibly of overwork – and was buried in Chesterton Cemetery.

He left an estate which would be worth around £130,000 today [8], but which almost certainly included the value of his house. Ernest was now, at 21, the head of the family and the inheritor of the printing press and the carving & gilding workshop. He must have been taught everything his father knew, since he kept both businesses going – and more, caused them to flourish. Six years after his father’s death, Ernest, together with his younger brother, Frederick Mortimer Savory, appear in the Cirencester trades directory for 1889 (extracted from Kelly’s Directory of Gloucestershire):

He left an estate which would be worth around £130,000 today [8], but which almost certainly included the value of his house. Ernest was now, at 21, the head of the family and the inheritor of the printing press and the carving & gilding workshop. He must have been taught everything his father knew, since he kept both businesses going – and more, caused them to flourish. Six years after his father’s death, Ernest, together with his younger brother, Frederick Mortimer Savory, appear in the Cirencester trades directory for 1889 (extracted from Kelly’s Directory of Gloucestershire):

Savory Ernest W. Printer Publisher Book Seller & Gen Stationer 1&2 St John Street

Savory Ernest Wyman Carver & Gilder, Picture Frame & Looking-Glass Manufacturer 1&2 St John StreetSavory Frederick Mortimer Art Photographer 8 Castle Street

Bonhams, Knightsbridge, Sale 17879: ‘Period design’, lot 68

In proof of Ernest’s success, Bonhams sold in 2010 a pair of ‘late Victorian giltwood and composition girandoles by E.W. Savory of Cirencester’, which bears out his dedication to his father’s workshop – and possibly proves the worth of the knowledge behind The Practical Carver and Gilders’ Guide. The lot notes record labels (which have sadly not been photographed) on the backs of the girandoles, describing their maker:

E.W. SAVORY

CARVER & GILDER,

St John Street, CIRENCESTER,

Framing, Gilding and Re-gilding…

Patronised by H.R.H. the PRINCE OF WALES

It would be very nice to know in what way, exactly, Ernest had been patronized by the Prince of Wales, but it was certainly an accolade which his father would have appreciated. Another specimen from the workshop was sold by Christie’s in 1999; the label on this looking-glass credits ‘Savory Carver and Gilder’, and may therefore date from the time immediately after Charles’s death in 1883, when Ernest was not yet resigned to using his own name instead of his father’s. In this case, it may after all have been C.H. Savory who had received royal patronage.

Ernest married a Cirencester girl in 1888, and they had seven children. The printing business grew. Ernest printed – for example – a series of eight county maps, which utilized every spare scrap of space for advertising, and sold for sixpence each. He continued to diversify, and produced chromolithographic postcards – comic, glamorous, landscape, and reproductions of works by contemporary artists; also, for instance, signed portraits of composers.

E.W. Savory, Ltd, Fine Art Publishers, Park Row Studios, Bristol, on V.E. Day, 1945. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

E.W. Savory, Ltd, Fine Art Publishers, Park Row Studios, Bristol, on V.E. Day, 1945. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

In 1889 he opened an outpost of the Stream Press in Bristol, and in 1895 moved the whole business from Cirencester to Bristol. By the time the 20th century opened he and his family were living in the elegance of no 4, Rodney Place, Clifton, now occupied by the Rodney Hotel, and by 1906 E. W. Savory Ltd (no longer the Steam Press) had moved into Park Row Studios, now part of the University of Bristol [9].

Ernest Wyman Savory (left) in his studio, with the artist Tom Mostyn, c. 1910. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

Ernest Wyman Savory (left) in his studio, with the artist Tom Mostyn, c. 1910. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

The carving and gilding workshop seems to have been abandoned with the move from Cirencester. Ernest himself painted, but there is no indication as to whether he framed his own paintings [10]. The business had come a very long way from C. H. Savory’s first printing workshop in Cirencester; but although Ernest was entrepreneurial, driven and ambitious, he was building on his father’s own related qualities – and perhaps also on some of the rewards reaped by the unlikely success of a small craftsman’s manual.

Charles Henry Savory in the 1860s. Photo courtesy of Richard Savory

******************************************************

With grateful thanks to Richard Savory for his help with his family’s history and for the use of so many photographs.

[1] There seem to be no publication dates connected with the book until 1900, long after Savory’s death. In his December 2012 addenda to his book, The Art of the Picture Frame, Artists, Patrons and the Framing of Portraits in Britain, National Portrait Gallery, 1996, Jacob Simon gives this assessment of dating the various editions: ‘The Practical Carver and Gilder’s Guide seems to have been issued in a series of editions as follows: 1st ed., 1873 or later (probably 1874), 140 pp + [xii] pp adverts; 2nd ed., 1874 or later (perhaps 1875), 176 pp; 3rd ed., 1874 or later (perhaps 1876), 176 pp + [viii] pp adverts; 4th ed., c.1877, 201 pp + [i] p. adverts; 5th ed., c.1877 or later, 205 pp + [iii] pp adverts. Authorship of the 5th edition is given to Charles H. Savory: earlier editions are described as ‘By a Practical Hand’.’ See addendum for p.194, note 38.

These dates truncate even further the time lapse between editions than the generally promulgated dates used by secondhand bookshops (1874-85), and reveal how popular and what a bestseller it must have been.

[2] Richard Savory, ‘I fairly blessed that bullet’: Harry Savory’s war, unpublished booklet, Foreword, p.3.

[3] Malcolm Kitch, ‘Apprenticeship and occupations in Southern England, 1710-1760’, Research Paper 24, Brighton, 1996, p. 5

[4] Ibid., p.8

[5] Savory’s family photograph was taken exactly 20 years after the earliest photograph of a man, taken by Daguerre in 1838, and seven years after the collodion process was introduced, bringing photography to a much wider audience.

[6] For example, in 1872, Savory published Notes on the Roman Villa, at Chedworth, Gloucestershire with a Catalogue Descriptive of the Articles Deposited in the Museum Attached to it. With a Plan, by Professor Buckman & Robert W. Hall; in 1877 he published Legends, tales, and songs in the dialect of the peasantry of Gloucestershire, with several ballads and a glossary of words in general use; he also published (undated) Joseph Stratford’s Gloucestershire Tracts: good & great men of Gloucestershire. These indicate that his publications were usually fairly slender, and local in scope. He also published a series of county directories for Gloucestershire (Savory’s County Almanack), which apparently first appeared in 1857 and carried on until 1917.

[7] They may also have included Amateur Handicraft, ‘By the Author of “The Lathe and its Uses”, “Turning for Amateurs”, etc.’, and The Amateur’s Practical Guide to Fretwork, Wood Carving, Marquetry, Buhlwork, Mitreing Picture Frames, Lattice and Verandah Work…, ‘By a Practical Hand’; and the earlier article, ‘Inscriptions: The Presbyterian Chapel, in History of the town of Cirencester, 1858.

[8] See The National Archives Currency Converter; this has not been updated after 2005, however.

[9] Richard Savory, op. cit., p. 5.

[10] Ibid. Ernest apparently had a painting accepted by the Paris Salon of 1927.