Figurative frames in the Low Countries

in the 16th & 17th centuries

by Dorien Tamis

Amongst frames made to hold a single painting (to differentiate them from those which are a part of a larger assemblage, i.e. an architectural ensemble, an altarpiece etc.), figurative painted frames stand out as a subcategory. Usually, early modern frames provide a clear boundary between the artwork they frame and the interior where they hang. The function of that boundary is to enhance the art which the frame contains, separating the painting from the outside world, and promoting the illusion of the inside world seen through the window-like opening of that painting. The figurative painted frame cannot perform these functions so effectively, but it can add an extra layer of iconographical meaning to an artwork.

In this article the term ‘painted frame’ is used for figurative painted frames, but of course there are other types of frame which could rightly be described as such. Many frames are coloured, evenly stained or painted, in part or as a whole. With frames painted to imitate other, often precious materials – such as, for instance, marble, stone or rare wood – the genre begins to blur into the category of trompe-l’oeil. And, as trompe-l’oeil effects frequently play an important rôle in figurative painted frames, a clear distinction between trompe-l’oeil frames and figurative painted frames is not always to be made.

Introduction

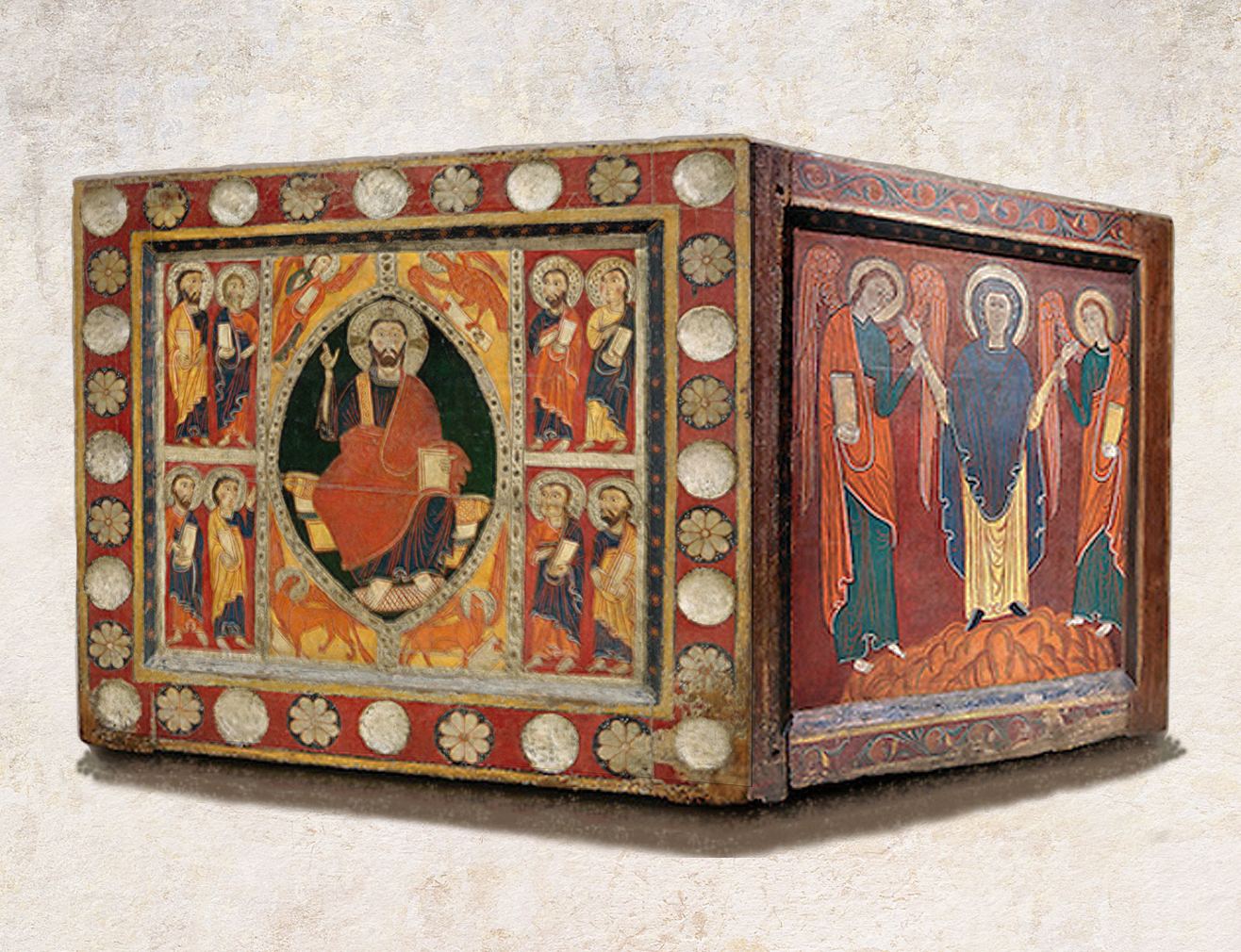

Altar of Encamp, from Sant Romà de Vila, Andorra, 13th century, Museu d’Art Catalunya, Barcelona

Sacred paintings and carvings where the central scene, executed on a large scale, was surrounded by small-scale scenes or figures of saints and angels, had existed from an early period, in the form of painted altar frontals and dossals (the façade of the altar and the retable on top of it), and small carved ivory diptychs and triptychs.

Unknown artist, Madonna del Carmelo, late 12th century? Santa Maria Maggiore, Florence

With the growing importance of the upright altarpiece fixed on or behind the altar, and the need for the frame to support and protect it, the auxiliary figures and scenes tended to migrate onto the frame itself, which provided an extra field for explanatory symbols and narrative. Domestic altarpieces would imitate this arrangement, just as they copied, on a small scale, paintings in the form of a church façade.

Bastiani

Lazzaro Bastiani (? c.1425–Venice 1512), Madonna & Child in a painted frame with eleven spiritelli, c.1465, painted panel 54.5 x 42.5 cm. with painted frame 81.2 x 69.5 cm., Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

One of the earliest surviving examples of an ensemble of a work set in a frame with figures decorating the frieze is the Madonna & Child in a painted frame with eleven spiritelli, attributed to the little-known Venetian painter Lazzaro Bastiani. The central panel, dating from c.1465, shows a lively but conventional Madonna and Child. To enhance the illusion of volume and depth in an otherwise nondescript dark recess, Mary is situated – standing? – behind a stone parapet. Having seated him on a (?)testament lying on the ledge, she is holding the Christ Child upright with one hand, the other resting loosely around the book.

The frame is separated from the painting by a simple, and unusually prominent multi-tiered sight edge, newly gessoed and gilded or even new in its entirety; it echoes the moulding at the top edge or outer contour. The spatial arrangement as painted on the frieze of the frame offers an illusion in the opposite direction from the painting, as it were. The figures of the spiritelli are painted as if looking inwards to the Madonna and Child, standing on small ‘platforms’ of clouds which seem to extend into the space the viewer is occupying. The small spiritelli show the instruments of Christ’s Passion, thus pointing forward in time to His death on the cross and mankind’s redemption through it, and they relate to Christ as a Child by looking into the recess where He sits. By constructing the spatial illusion in this manner, the painter created the semblance of separate but connected tiers of space and time, all within a single work.

Lazzaro Bastiani, Madonna & Child in a painted frame, c.1465, detail without outer moulding

The layering of different iconographical elements which involve the viewer might even be called playful, if the reference to death by crucifixion didn’t recall Christ’s destiny. What is interesting is that the difference in the two pictorial planes works with much greater visual effect when the outer moulding of the frame is omitted, than when the whole object is seen. When complete, the gilded outer contour of the frame disturbs the effect, pushing back and ‘confining’ the spiritelli. The regilded sight edge must be original, or the replacement of an original, as the right foot of baby Jesus is resting on it, further connecting both planes of the ensemble. But we could inquire whether the outermost (or top) moulding is also original, the more so as in later paintings of this type it is usually omitted or appears much more modest.

Bastiani’s work was shown in the Berlin Donatello exhibition of 2022, but absent from the displays in Florence and London [1]. Although it is not explicitly stated in the catalogue, his painting and frame were probably included to illustrate one of the themes of the exhibition: the dialogue between the arts of sculpture and painting.

Donatello (c.1386-1466), Pazzi Madonna, c.1422, marble, 74.5 x 73 x 6.5 cm., in antique frame reduced to fit, Bode Museum, Berlin

In the Berlin exhibition, the making and meaning of Donatello’s sculptural frames, as seen for instance in the Pazzi Madonna (1420/25), was a topic of interest which was emphasized to the viewer. At the time, the convincing sense of spatial depth Donatello was able to achieve in such a shallow relief was much praised. It makes one wonder whether Bastiani, in the spirit of Paragone – the competition between different art forms which was so important to the masters of the Italian Renaissance – wanted to prove that in this respect, painting could achieve even greater spatial projection than sculpture. To make his point, he incorporated the frame – the boundary between the space the viewer inhabits and the illusory space of the painting – in an inventive manner to show depth not only beyond the picture plane, as Donatello did, but also projecting into the space occupied by the viewer. Did sculptors claim volume and three-dimensionality as an advantage of their art? so too can the painter, as Bastiani seems to want to prove.

Flemish Mannerist strapwork frames

Flemish School, Adoration of the shepherds with painted frame, last quarter 16th century, o/panel/c, 55 x 41 cm., with frame 86.5 x 72.5 cm., Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy

Very little information is available on the anonymous Adoration of the shepherds with a painted frame in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nancy. The museum catalogues the work as Flemish, dating from the first quarter of the 17th century:, but, with its elongated figures on a white ground layer, it might be a lot earlier, and French, associated with the school of Fontainebleau and dating from c.1575-1600. The panel shows a nocturnal scene, the shepherds worshipping the infant Jesus in a stable which is close to the picture plane – a view which had been popular in both Germany and the Netherlands at the beginning of the 16th century, but had become less so at the time the painting must have been made.

Flemish School, Adoration of the shepherds, details of the long sides of the frame

On the dark frieze of the frame decorative Mannerist strapwork has been painted in gold, probably using examples of so-called ornament prints. The four corners of the frame show round medallions with the four Evangelists in grisaille. In an oval at the top centre, the monogram IHS is picked out on a golden glory amongst dark clouds, whilst ovals in the centre of the lateral rails show the Annunciation and the Visitation, the meeting of Saints Anne and Elisabeth. The rectangular cartouche at the bottom centre completes the inscriptions which appear on smaller cartouches at each side.

Bottom centre:

‘NASCITUR IN STABULO, NOCTU[M] SERVATOR JESUS, / QUI VITAM CUNCTIS, LUCEM Q[UI]S DAT, UNDI Q[UI]S SAECLIS’ (He was born in a stable; Jesus our Saviour came in the night, Who giveth life to all, Who giveth light, Who is for every age)’

Under the Annunciation:

‘AVE GRATIA PLENA / DOMINUS TECUM’ (Hail Mary, full of Grace/ the Lord is with you’

Under the Visitation:

‘BENEDICTA TU IN / MVLIERIBVS’ (Blessed art thou amongst women)

Under each of the Evangelists:

‘S. MARCUS / S. JOHANNES / S. LUCAS / S. MATTHEVS’ [2].

Although it doesn’t interfere too much with the overall impression, the gilded ogee moulding with small sanded frieze which acts as an outer containing frame is probably not part of the original painted frame.

Flemish Mannerist polychrome and gilded plate frame, 16th century; the frieze decorated overall with an intricate strapwork design supporting corner and centre medallions, with an inscribed cartouche at the bottom; the corners with roundels painted with the four evangelists; the lateral centres with ovals painted with the Nativity on the left & Christ rising from the tomb on the right; a glory inscribed ‘IHS’ at the top; 54 x 51 cm; Artcurial, 13 February 2018, Lot 157

Flemish Mannerist polychrome and gilded plate frame, 16th century; 54 x 51 cm; Artcurial, 13 February 2018, Lot 158

If the present frame is compared with two similar but empty strapwork frames, auctioned in Paris in 2018, the outer mouldings of the Nancy frame are missing in the two latter (lot numbers 157 and 158). Although the Paris frames are much smaller than the one in Nancy (respectively 55 x 43 cm. and 54 x 51cm. versus 86.5 x 72.5 cm.) the strapwork on all three frames is very similar. Artcurial dates the two lots to the end of the period suggested here for the Nancy ensemble: i.e. around 1600. The medallions of lot 158 (the upper image) show almost identical pictures to the Nancy frame, but on a smaller scale, and they are also more coarsely executed.

The medallions on this frame were painted in colour rather than grisaille; the four corners once again hold roundels with the four Evangelists, but the oval medallions at the lateral centres show the Nativity and the Resurrection of Christ.

The inscriptions beneath these last two miniatures are unreadable, but the large rectangular cartouche at the bottom centre is inscribed:

‘AGNOVERE DEU[M], PROCERES, PRONIQUE DEDERE AURU[M], THUS, MYRRHA[M], DIVINI SIGNA RECORIS’ (‘In acknowledging your God, oh exalted ones, and indeed in giving gold, frankincense, myrrh, you recall the signs of Godhead’

This indicates that the painted scene contained by the frame must have been an Adoration of the Magi.

Despite the difference in scale, the similarities between the Nancy frame and the Artcurial pair suggest that the type and design of these painted frames were a stock-in-trade, and that they were manufactured in multiple versions, and in various sizes.

Frans Francken and Gillis Mostaert: moveable frames

During the last third of the 16th and into the early 17th century, combinations of religious pictures with painted frames enjoyed somewhat of a fashion in Antwerp. At least four dozen of these combinations survive, coming at first from the workshop of the Antwerp master Gillis Mostaert and then from that of Frans Francken II and his family in the 1620s and 1630s.

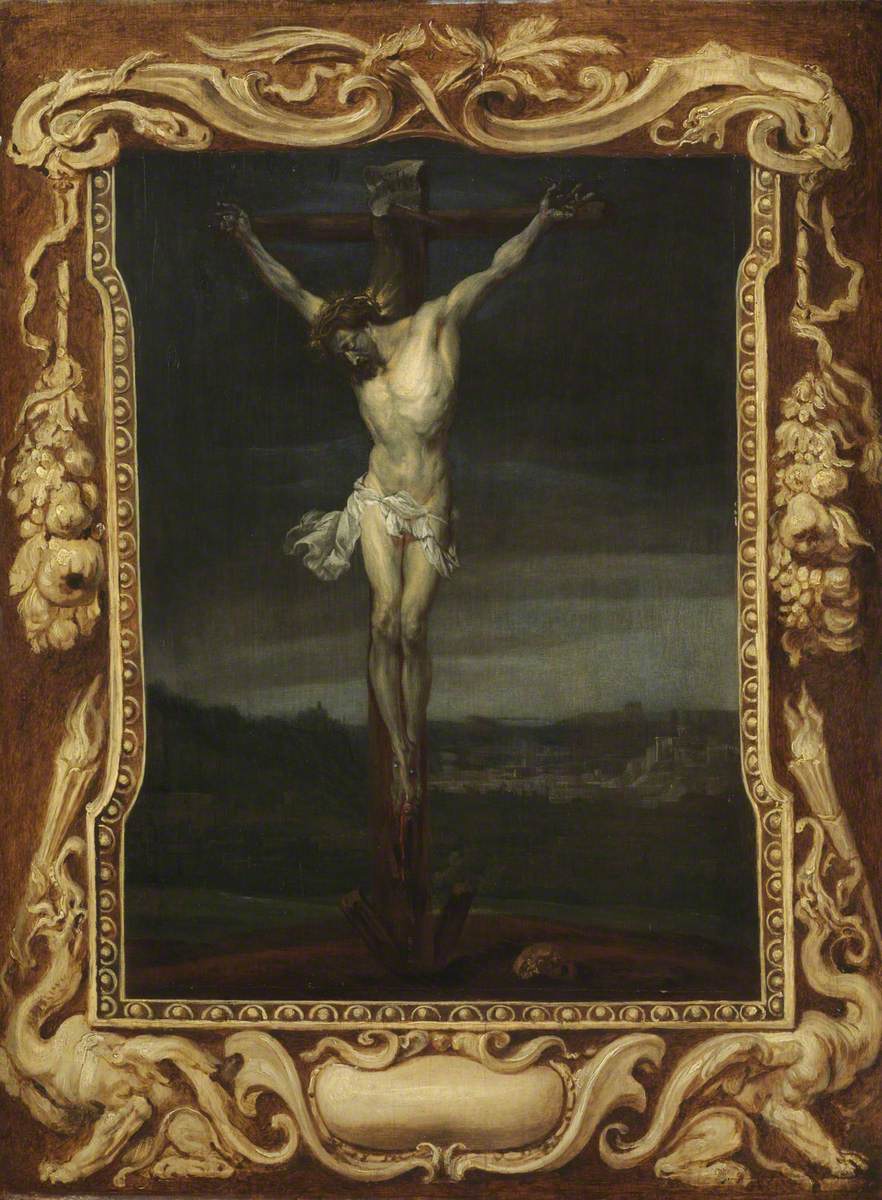

Hendrick de Clerck (1560-1630), Christ on the Cross, c.1610, Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Hannover

Gillis Mostaert (1528-98), The Crucifixion, panel, 52.5 x 39 cm., Lempertz Auction, Cologne 18 November 2017, Lot 2023

A singular example attributed to Hendrick de Clerck, now in the Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum Hannover (above), seems very close at least to the frames of a portrait-format Crucifixion in Louvain, an ensemble which was auctioned by Christie’s in New York in 1995, and of a painting in the Schloss Cappenberg in Dortmund, all three attributed to Gillis Mostaert. To determine whether the current combination was put together later, or whether the attribution to De Clerck should be reconsidered, further study is needed.

Gillis Mostaert & workshop (1528-98), The road to Calvary, with scenes from the Passion of Christ, c.1578-79, o/ panel, 56.2 x 75 cm., with moveable frame: 81 x 99 cm., Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne, on loan from Fondation Corboud

Gillis Mostaert (1528-98), The Baptism of Christ, 1598, with moveable frame: scenes from the Life of Christ and the Old Testament; o/panel, 51.5 x 66 cm., Fondation Custodia

Gillis Mostaert (1528-98; & workshop), Miracle of loaves & fishes, with Last Supper top centre of frame; o/panel, 27.2 x 39.1cm.; with moveable frame 45.7 x 59.1 cm., Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle

Gillis Mostaert (1528-98; & workshop) OR Frans Francken II 1581-1642), Crucifixion, with moveable frame: scenes from the Passion of Christ and the Instruments of the Passion, o/panel, with frame: 69.9 x 54.6 cm., Musée des Beaux-Arts de Ghent

Gillis Mostaert (1528-98: & workshop), Crucifixion, with moveable frame: scenes from the Passion, including Christ in Limbo and the Resurrection, and detail, Musei di Strada Nuova, Palazzo Bianco, Genoa

Gillis Mostaert (1528-98; & workshop), Crucifixion, with the Arma Christi, o/panel, 83 x 68cm.; with binnenlijst /inner frame, and buitenlijst /outer frame, 98.5 x 84 cm., M-Museum, Leuven

In 17th century inventories this type of painted frame was called a binnenlijst or cant (an inner frame), as opposed to a buitenlijst (outer frame) , which implies a conventional moveable frame [3].

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), The Passion of Christ, with moveable frame: scenes from the Life of Christ, o/panel, 73 x 103 cm., M-Museum, Leuven

A rare example of paintings which retain both binnenlijst and buitenlijst are the Francken and Mostaert Crucifixions, both in Museum M in Leuven [4].

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), Adoration of the Magi, with moveable frame: scenes from the Life of Christ with the Evangelists, o/panel, 22 x 36.2 cm.; with frame: 48.5 x 63 cm., Abbey of Our Lady, Tongerlo, Westerlo

Although the productive period of each painter’s workshop does not overlap, differentiating between the two with regards to the ensembles of painting and painted frame turns out to be difficult. Proposed as a rule of thumb, Carl van de Velde stated that those paintings where frame and painting are made separately should be attributed to Mostaert, whereas those where the frame was painted in trompe-l’oeil on the same support as the central picture – an integral frame – should be associated with Francken [5]. An inventory of paintings and frames, based on the groundbreaking article by Van de Velde, the excellent master’s thesis by Sophie Suykens and data from the databases from the Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie in The Hague show that this rule does not hold, and attributions are by no means undisputed [6].

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), Crucifixion, with moveable painted frame and additional tabernacle frame, o/panel, 67 x 61cm., Duran Arte y Subastas, Madrid, 25 March 2021, Lot 3

Frans Francken and Gillis Mostaert: integral frames

Frans Francken (1581-1642; and workshop), Apelles painting Campaspe, 1620-29, integral frame with scenes from the life of Alexander, o/panel, 72.5 x 60.5 cm., Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Frans II (1581-1642) & Hieronymus Francken (1578-1623), Parable of the Prodigal Son, integral frame with scenes from the narrative, c.1610-20, o/panel, 60.4 x 85.9 cm., Rijksmuseum

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), Parable of the Prodigal Son, integral frame with scenes from the narrative, 1633, o/panel, 61 x 86 cm., Musée du Louvre

Frans Francken II (1581-1642; and workshop), Parable of the Prodigal Son, integral frame with scenes from the narrative, o/panel, 49 x 62.5 cm.; no date; no location

With one exception – Apelles painting either Campaspe or Roxane – the subjects of these paintings are always religious: the Life and Passion of Christ, the Life of the Virgin, and the Parable of the Prodigal Son are the most frequently occurring. The dramatic highlight of the story is shown in the central picture; the frame shows secondary scenes, events, and sometimes related saints or Biblical figures, most often painted in grisaille or camaïeu. Interestingly, in the few instances where we have contemporary descriptions from estate inventories of the early 17th century, the frames are called ‘white’, ‘yellow’ or ‘blue’.[7] As these descriptions, all of painting said to be by Mostaert, his workshop or followers, cannot be matched to actual, preserved paintings, the colours have to be guessed.

Gillis Mostaert (1528-98), The Baptism of Christ, 1598, with moveable frame: scenes from the Life of Christ and the Old Testament; o/panel, 51.5 x 66 cm., Fondation Custodia

The Custodia Baptism must surely have a yellow ‘binnenlijst’, whilst the white and blue frames may refer to gradations of grisaille. Some of the ensembles can be compared to similarly laid-out devotional prints from the end of the 16th century made by members from the Wierix family [8].

Frans Francken II (1581-1642; and workshop), Adoration of the Magi, o/panel, 115 x 88.5 cm., Kunsthandel K & V Waterman, Amsterdam

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), The Last Supper, integral frame with the Evangelists in the spandrels, God the Father, top centre, and death & Satan, bottom centre, c.1625, o/copper, 54 x 40 cm., Johnny van Haeften, London

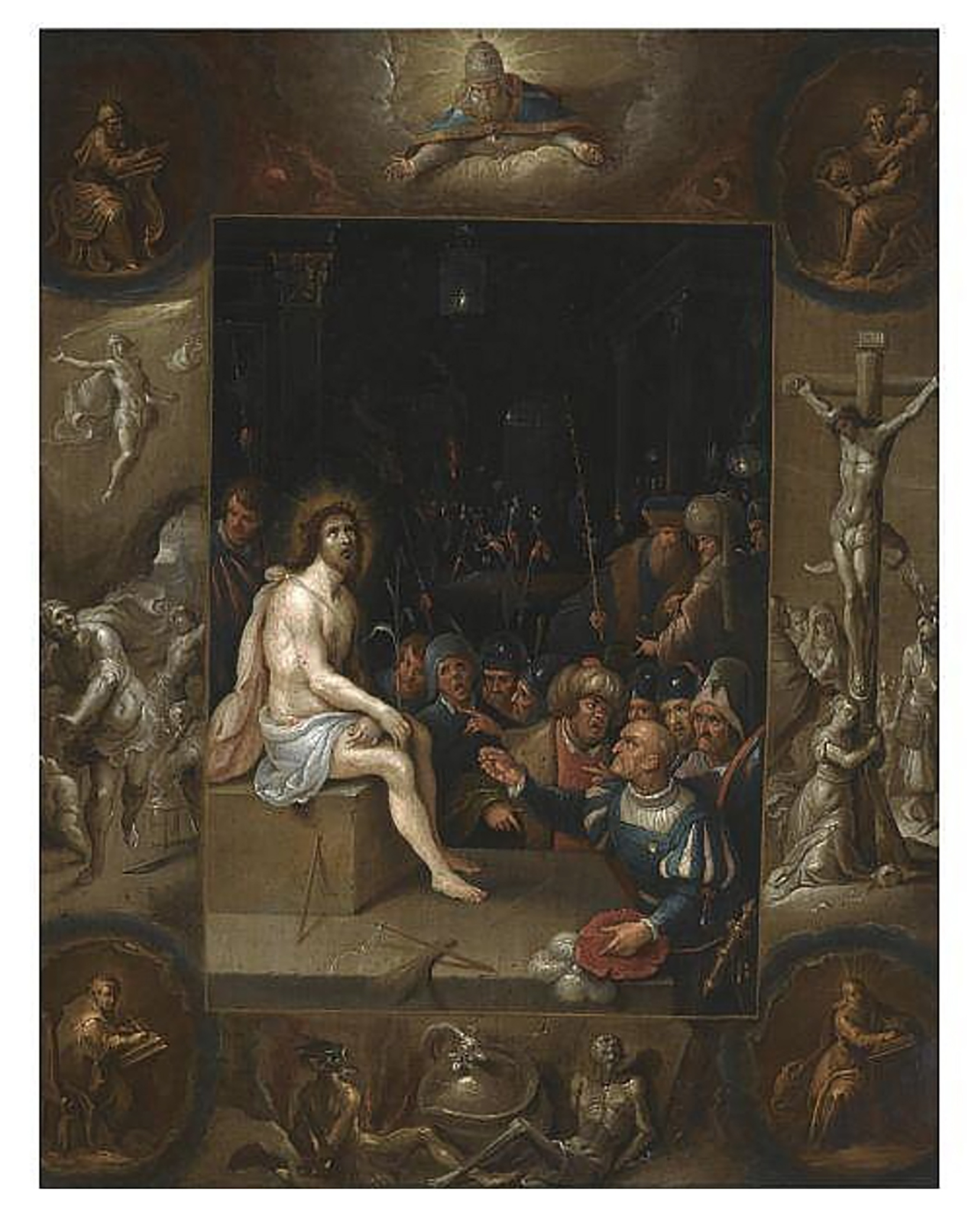

Frans Francken II (1581-1642; and workshop), The mocking of Christ, integral frame with the Crucifixion, Resurrection and the four Evangelists, o/ copper, 37 x 29 cm., Sotheby’s New York, 22 April 2009, Lot 87

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), The mocking of Christ, integral frame with the Crucifixion, Resurrection and the four Evangelists, National Museum in Warsaw

The fact that the frame in these ensembles does not function in a conventional manner, by forming a border between the viewer and the painted illusion (and thus enhancing the illusion), is very much intentional. At the beginning of the 16th century, an important criticism by the Protestant reformers of the Catholic Church was of the idolatry they perceived to be engendered by the paintings and sculpture as displayed in churches. Instead of worshipping God, the reformers noted, people gave their devotion to the physical pictures and statues of the saints and the Virgin Mary. In the Counter-Reformation of the second half of the 16th century, the Catholic Church addressed this and other criticisms in various ways.

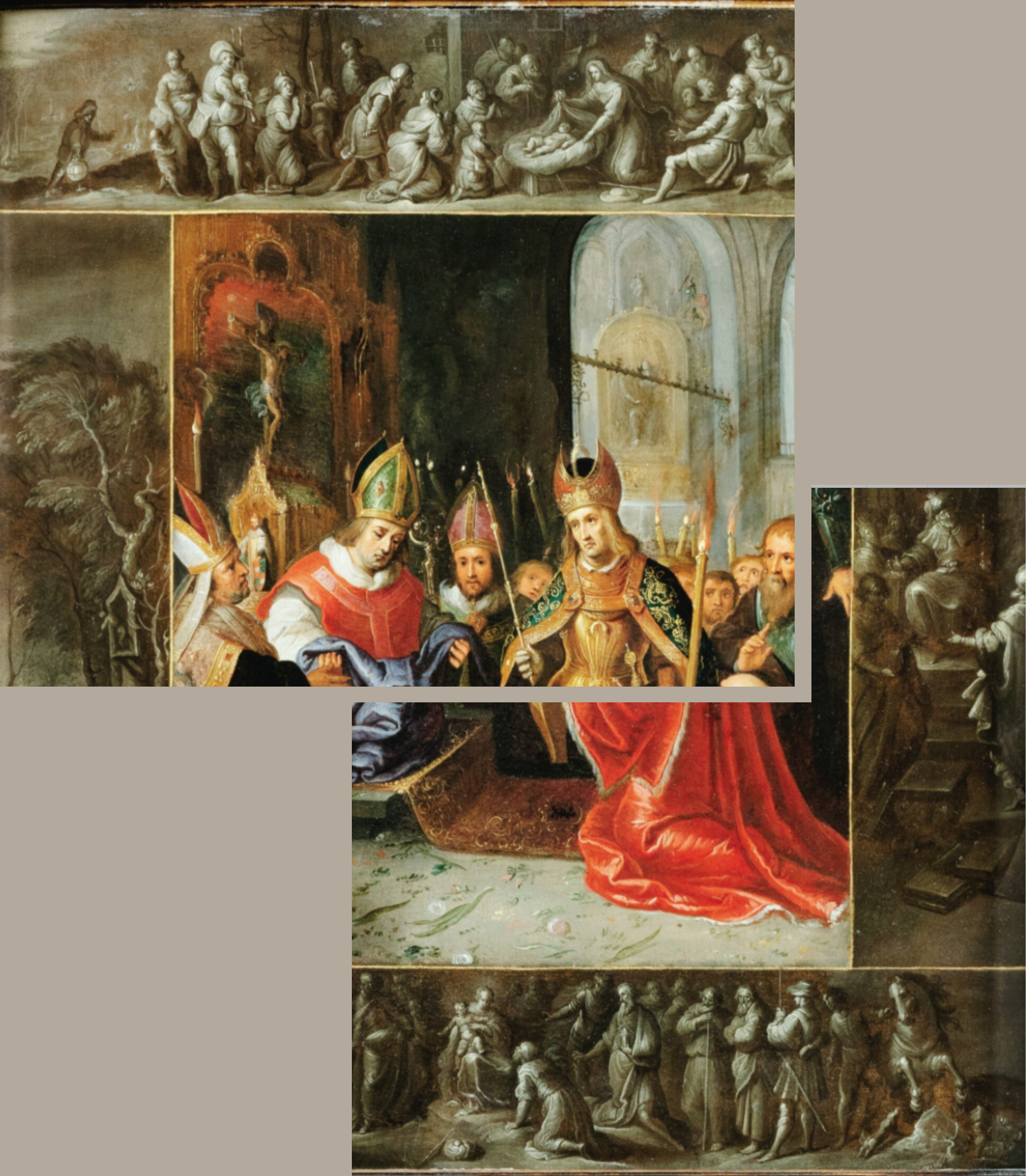

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), Emperor Charles V shown the Virgin’s robes, integral frame with scenes following the Nativity, o/panel, 52.5 x 42 cm., and details, Sotheby’s Paris, 3 December 2020, Lot 28

It is from this viewpoint that Sophie Suykens explains this type of frame, and the painting-frame ensemble. By refusing to enhance the illusion with a conventional frame, but instead using a painted border to fracture the illusion, Mostaert and Francken made it clear to the well-versed Catholic that the ensemble was a corporeal, earthly object. It was not to be venerated in itself: the painting and its frame were no more than a conduit to direct the thoughts of the believer to the divine [9]. Such a complicated intellectual exercise fits in very well with the 16th century’s predilection for convoluted thought-play and argument. Even so, it remains to be seen whether all these paintings were made with this theological finesse in mind, or as a answer to a fashionable demand for a certain ‘gimmick’.

Hieronymus Francken II (attrib.; 1578-1623), Parable of the wise & foolish virgins, c.1593-1623, panel, 52 x 72 cm., Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Both the format and, as already stated, the existence of further replicas of the same image, suggest that these ensembles might have been made ‘on spec’, for the open market. The predominantly religious subject matter as well as the theological explanation as given by Suykens indicate that these paintings were primarily intended to function in a devotional context, which is confirmed by a painting attributed to Hieronymus Francken now in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Kopenhagen [10].

Hieronymus Francken II (attrib.:), Parable of the wise & foolish virgins, detail with the Mocking of Christ in a painted frame

In the background of this Parable of the wise and foolish virgins, a painting of the Mocking of Christ in a painted frame very much like the combinations attributed to Hieronymus’s younger brother, is placed on an altar, in a chapel or a cloister. In fact, the Abbey of Tongerlo, to the west of Antwerp, still has a Francken Adoration of the Magi with a painted frame in its possession (illustrated earlier).

In contrast, both owners of paintings with ‘binnenlijsten’ and ‘buitenlijsten’ from whose inventories Van de Velde cites (cf. supra), are considered art-collectors first and foremost, without an overtly pious bias. The ten pieces with ‘binnenlijsten’ which the art collector Philips van Valckenisse owned upon his death are almost all described as by or after Gillis Mostaert, and were probably bought from the painter’s estate. Van Valckenisse also possessed secular landscapes by Joos de Momper which are cited as having ‘binnenlijsten’. Jacob (or Jacques) Snel, whose 1623 inventory mentions just one painting with a binnen– and buiten-lijst by Mostaert, had been a ‘wijntavernier’, a wine-seller or wine-merchant [11].

Frans Francken II: the ‘strooiborder’ frame

Frans Francken II (1581-1642: central scene with Madonna & angels), Ambrosius Francken II (fl. C. 1590-1632), & Abraham Govaerts (1589-1626), workshop, Madonna & Child with two angels, integral frame with scenes from the life of Christ, o/panel, 42 x 48.5 cm., and detail, Lempertz, Cologne, 14 May 2011, Lot 1049

Frans Francken II (1581-1642; and workshop), Madonna & Child, integral frame with scenes of the Nativity, c.1620, o/copper, 38 x 46 cm., Christie’s, 17 April 1997, Lot48

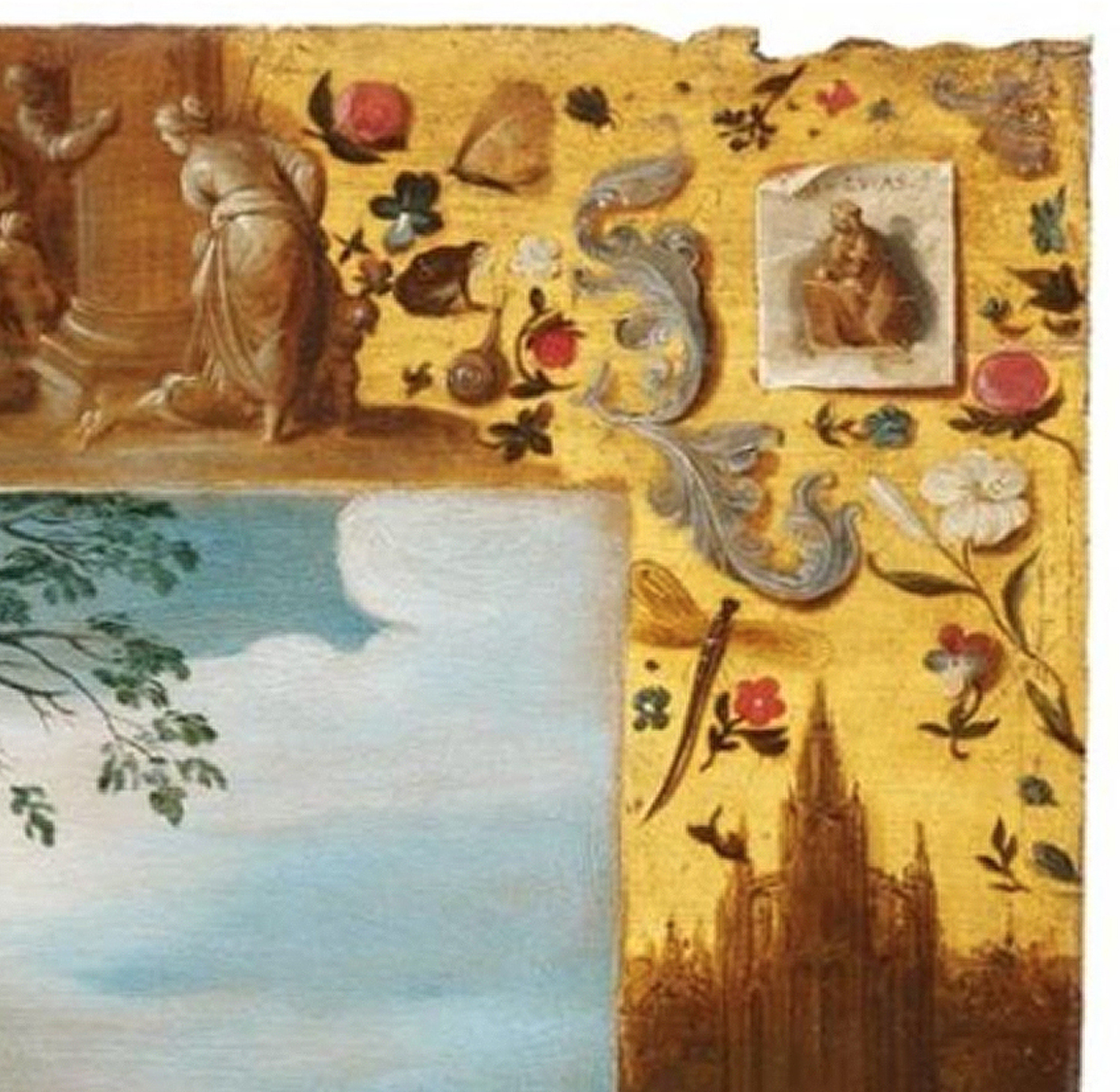

In a small subset of six paintings with painted frames, the areas between the grisaille scenes were decorated like a so-called ‘strooiborder’ from a late 15th century Bruges manuscript, where the margin around the page of an illuminated book was painted in a trompe-l’oeil technique, as if strewn with small objects and flowers.

Frans Francken (1581-1642), Madonna & Child served by two angels, integral frame with scenes from the life of Christ, c.1620, 47.2 x 56.3 cm., National Museum of Slovenia

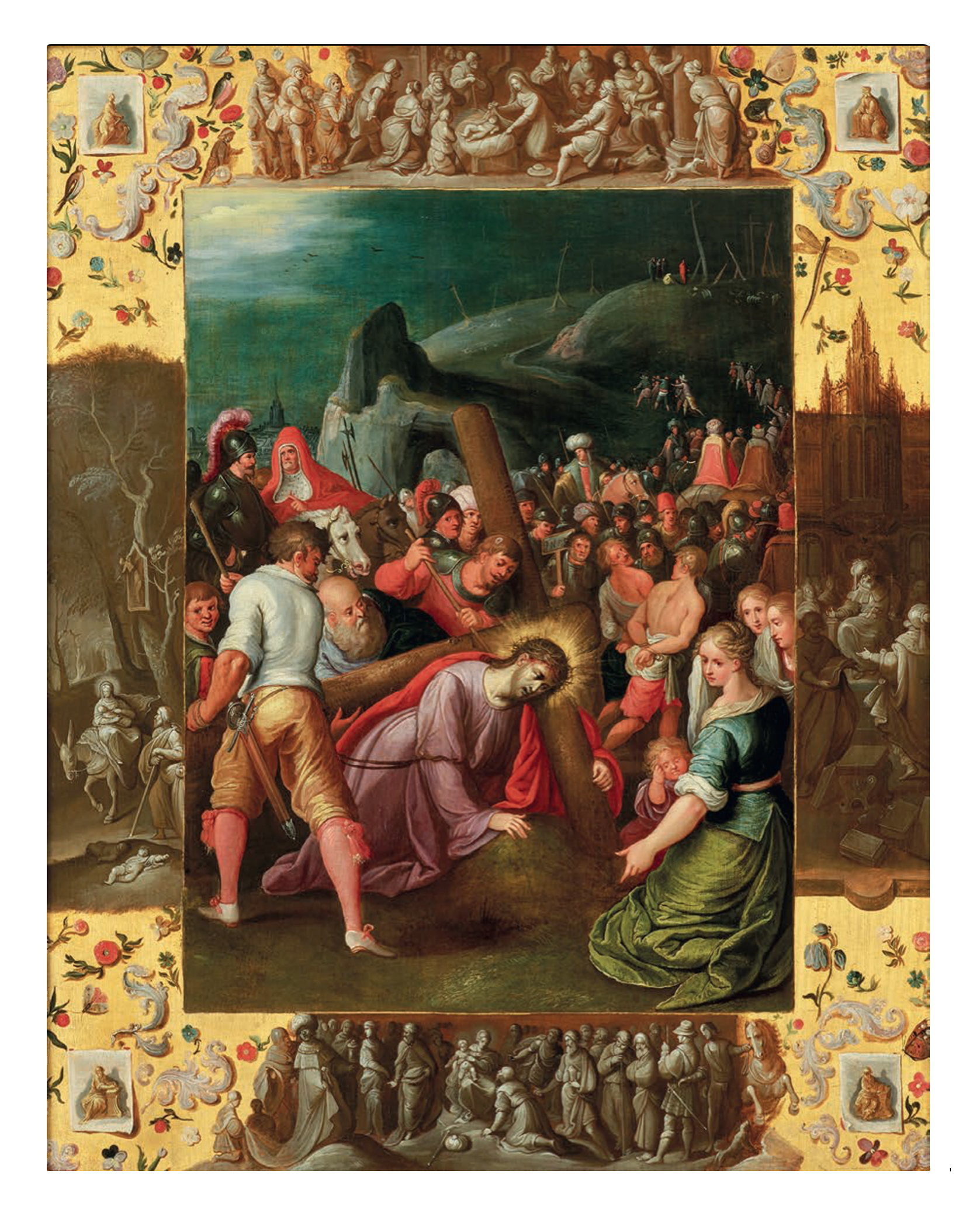

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), The road to Calvary, integral frame with scenes from the life of Christ, early 17th century, o/panel, 53 x 41.7 cm., Rafael Valls Gallery, London, 2023

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), Christ in the house of Simon the Pharisee, integral frame with scenes from the story of the Nativity, 54 x 41.9 cm., Sotheby’s New York, 14 October 1999, Lot 91

All of these are attributed to Frans Francken II or his workshop, and with all of them the painted frame is part of the same support as the primary scene. In both the ‘common’ painted frame and the ‘strooiborder’ painted frame, the iconography can be called ‘reactionary’, in the sense that the ensemble either refers back to a much older and obsolete form of art, or looks distinctly old-fashioned by combining scenes on different scales.

As either a satirical or a reassuring – because of its familiarity – artifice, falling back on old-fashioned forms and motifs has been used as a part of the visual vocabulary of the arts until today. For the paintings attributed to Mostaert and Francken, it must have been the reassurance of a past where the theological concepts of the Catholic church had not been challenged which prompted these painters to refer back to older styles.

Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641; attrib.), Christ on the Cross, c.1630-32, in feigned integral Mannerist frame with ‘shaped’ sight and monsters, o/panel, 62.6 x 45.6 cm., and detail, The Courtauld Gallery, London (Samuel Courtauld trust). Photo: The Courtauld

There is a rare deviation from this idea of comfort offered by a less troubled past in an ensemble where a crucifixion is surrounded by an integrated painted Mannerist frame. Attributed to Anthony van Dyck, this attempt to modernize Gillis Mostaert’s and Frans Francken’s model was either a special one-off, or it lacked the overall impact on buyers which this type of painting was looking for, and saw no repeats [12].

Cornelis de Man: a trompe-l’oeil frame

Jacob van Speeuwen (1609/11-post 1650), Self-portrait painting St Jerome, o/panel, c.1642, 34.5 x 28 cm., in trompe l’oeil setting with curtained inner frame in a scuptural niche with putti, by Cornelis de Man (1621-1706), c. 1655, 82.5 x 65 cm., Lawrences Auctioneers, Crewkerne, 19 January 2022, Lot 688

It is legitimate to ask how many of these ensembles might have been separated over time, partly lost or reassembled with other ‘spare parts’. And not every painted frame was intended for a painting by the same hand, as in the example, above, by Bastiani. A curious example of a ‘creative’ assemblage of disconnected parts came to auction in 2022 – a studio interior called a Self-portrait whilst painting St. Jerome by Jacob van Spreeuwen, in a frame painted by Cornelis de Man. And curiouser and curiouser, the then owner had the picture in its trompe l’oeil frame encased in yet another frame: a British Louis XIV-style giltwood pattern.

Cornelis de Man (1621-1706), trompe l’oeil painted frame, c. 1655, 82.5 x 65 cm., with Jacob van Speeuwen Self-portrait

Cornelis de Man’s frame is a tour de force of trompe-l’oeil, showing contrasting textures and different illusionistic layers. It has been painted with a decorated and garlanded architectural stone aedicule or classical niche, which rests on a ledge. Propped on the left and right pedestals of this aedicule is an inner ebony frame, apparently free-standing relative to the stone niche, and fitted with a brass curtain rod, its blue curtain pulled aside by one of eleven putti (ten boys and a girl) who swarm over the niche. The ledge where the niche sits doubles as a woman’s dressing table, with a powder brush, a jewellery box and a pearl necklace. The addition of a luxurious pocket watch warns the beholder of the transience of youth and beauty.

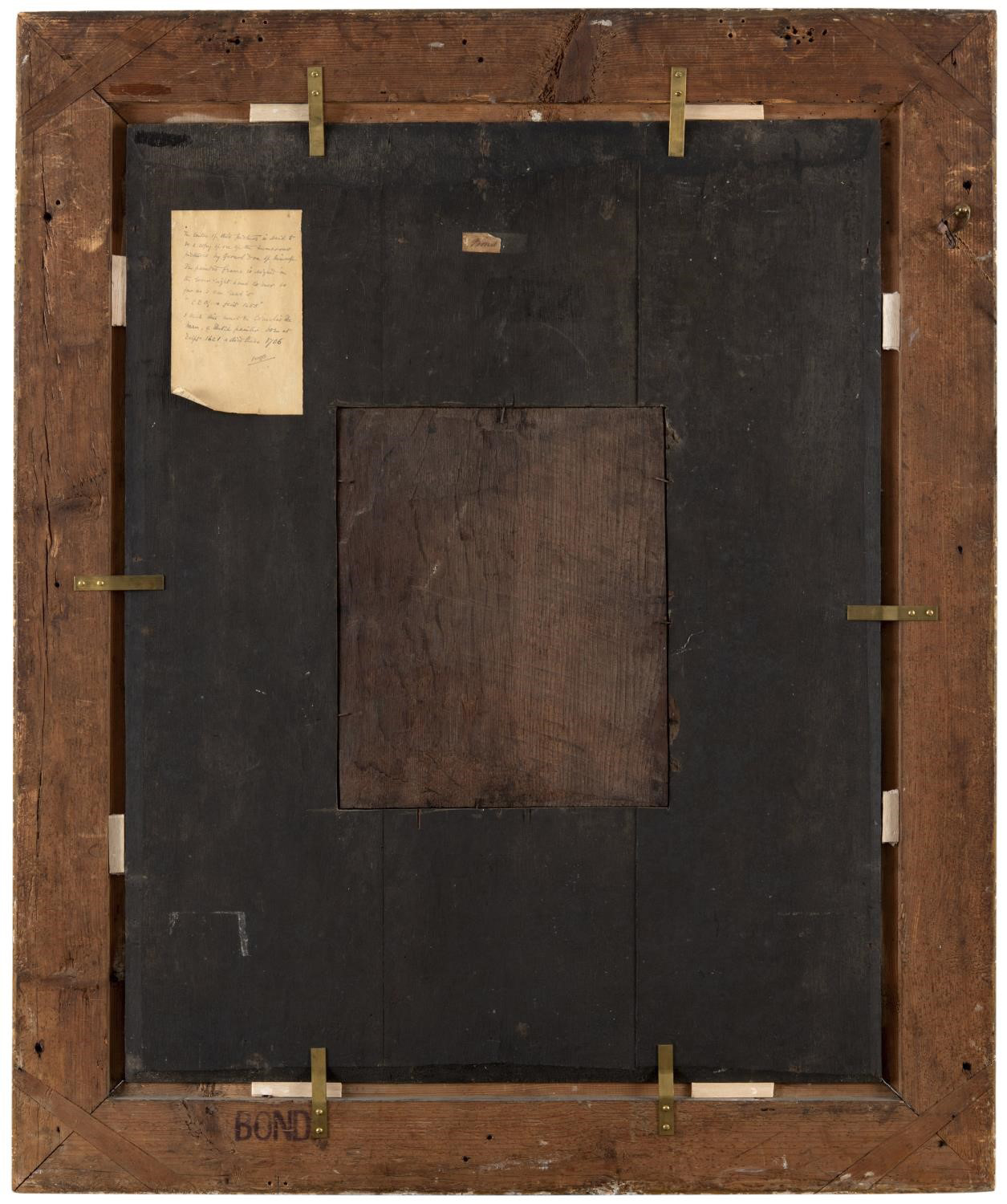

Reverse of the three elements of giltwood frame; Cornelis de Man trompe l’oeil frame; and Jacob van Speeuwen painting

The gilded moulding at the sight edge of the frame cuts brutally through the blue curtain in the upper right corner, breaking the illusion of an otherwise well-thought out composition. It suggests that the moulding is a later addition; possibly even that the sight may have been enlarged slightly to take the self-portrait. However, the reverse, as illustrated on the auctioneer’s website, does not offer any clues to such an intervention.

Both iconographically and stylistically, the interior attributed to Van Spreeuwen has little to do with the frame by De Man. No wonder then that Johnny van Haeften, the art dealer who bought the ensemble in 2022, separated the parts, and sold the frame by Delft-born and -bred De Man on to the Museum Prinsenhof in that city, the underbidder at the auction. The iconography of the toilet items and timepiece is a familiar one for carved looking-glass frames, and the Museum is therefore convinced that De Man’s work was also originally produced as a looking-glass frame [13]; in this case, the lost portion of the curtain might have been painted across the top right-hand corner of the glass [14]. Painted looking-glass frames are rare: only one other example by De Man is known, which was with the Zürich art dealer Bruno Meissner in 1981 ; its present location is not known[15].

In a few of his interiors, these being one of De Man’s specialities, the painter plays with the effects of a looking-glass reflecting figures and space otherwise invisible to the beholder: for example in the Game of Cards in Polesden Lacey, or the Geographers in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg. These looking-glasses, however, are framed in plain, dark moulding frames, once more confirming the uniqueness of the painted trompe l’oeil frame.

As evidenced by the De Man frame, but also by other examples in this article, many ensembles of painted frame and painting (or looking-glass) were separated over time. This is lamentable, not only as an aesthetic defect, but because it also destroys the often intricate iconological interplay between frame and framed. It makes it all the more important to draw attention to the unicity of these types of ensembles, and to make us aware of the need for curators and conservators of recognizing and keeping these together as much as possible.

**************************************************

As a freelance art historian and journalist, Dorien Tamis writes about nearly anything that catches her interest: from 16th century warfare to artful embroidery, from justifiably forgotten painters to historical movies. In the last few years she has mainly worked for the Bonnefanten museum in Maastricht, as a curator for the exhibitions Bruegel and contemporaries. Art as Covert Resistance? (2021-2022) and The Seven Deadly Sins in Bruegel’s Day (2024-2025).

Dr Tamis specializes in the workshop practices of 16th and 17th century Netherlandish painters, and was awarded her doctorate for the thesis, Van twee handen geschildert: werkverdeling tussen schilders in de Nederlanden in de zestiende en zeventiende eeuw (Painted by two hands: division of labour among painters in the Netherlands in the 16th and 17th century) in 2016.

[1] Florence: Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi and Musei del Bargello (19 March – 31 July 2022): Donatello. Il Rinascimento; London: Victoria and Albert Museum (11 February – 11 June 2023): Donatello: sculpting the Renaissance; Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, Donatello. Inventor of the Renaissance 2 Sept. 2022 – 8 Jan. 2023; S. Hoffmann, in Donatello. Inventor of the Renaissance, N. Rowley ed., 2022, pp. 228-29. See also ‘Framing relief sculptures’

[2] See the catalogue entry on the website of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy

[3] Carl van de Velde, ‘Taferelen met grisaillelijsten van Gillis Mostaert’, in A.-M. Logan (ed.), Essays in Northern European art presented to Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann on his sixtieth birthday, Doornspijk 1983, pp. 278-79. Van de Velde also cites binnenlijsten inventoried with paintings by Joos de Momper, but these ensembles did either not survive, or these binnenlijsten do not refer to a painted frame

[4] See Hélène Verougstraete, Frames and supports in 15th- and 16th-century Southern Netherlandish painting, Brussels 2015, pp. 648-49, with a description of the construction of the ensemble

[5] Van de Velde, op.cit., pp. 276-77; the term integral frame for a frame which is part of the support of a painting is taken from Verougstraete, op. cit., note 6, p. 64

[6] Van de Velde, op.cit.., pp. 276-82; Sophie Suykens, Gekaderd in grisaille. De schilderijen met monochrome lijsten van Gillis Mostaert en Frans Francken II, unpublished masters dissertation, Ghent University, 2016; search RKD Research under ‘Gillis Mostaert’ and ‘Frans Francken II’ (November 19 2024)

[7] Suykens op. cit., pp. 14-15.

[8] Suykens op.cit., pp. 27-29

[9] Suykens, op.cit. .pp. 31-66; Tamis in L. Hendrikman & D. Tamis, Bruegel and contemporaries: Art as a covert resistance, Maastricht/Zwolle, pp. 194-95

[10] Suykens, ibid., pp. 7-8

[11] See Van de Velde, op.cit., pp. 278-79; Suykens op.cit., pp. 13-14; and for Jacob/Jacques Snel, see M. Rooses, ‘Schilderijen in oude Antwerpsche familiën’, in: Onze Kunst 1 (1902), p. 109

[12] For dendrochronological data on the panel, see the website of Jordaens/Van Dyck Panel Paintings Project (December 8 2024)

[13] Museum Prinsenhof compares the De Man frame to what it considers to be a carved looking-glass frame, dated 1650-70, in Museum Rotterdam (February 17, 2025). However, the iconography of this frame is not entirely clear, and contains not only toiletries and accessories, but items like scissors, other tools and small containers which might refer to some sort of handiwork or craft. Did this frame really contain a glass, or maybe a painting, after all? Much more obvious is the Filippo Parodi frame of the Judgement of Paris (Genoa, Palazzo Spinola), which today contains a portrait of Maria Mancini by Ferdinand Vouet. It was originally made to contain a looking-glass, so that Paris would appear to be telling Hermes to give the golden apple to the beauty reflected in the glass, rather than to Aphrodite

[14] Suggested by George Shackelford in 2022

[15] See Julia van Marissing’s article on the frame by Cornelis de Man, ‘Spiegeltje, spiegeltje aan de wand’ (Museum Prinsenhof)

Frans Francken II (1581-1642), Pietà surrounded by grisailles of the Four Evangelists and scenes from the Old Testament, 1600-42, 50.2 x 37.5 cm., Lempertz, Cologne, 16 May 2018, Lot 1028