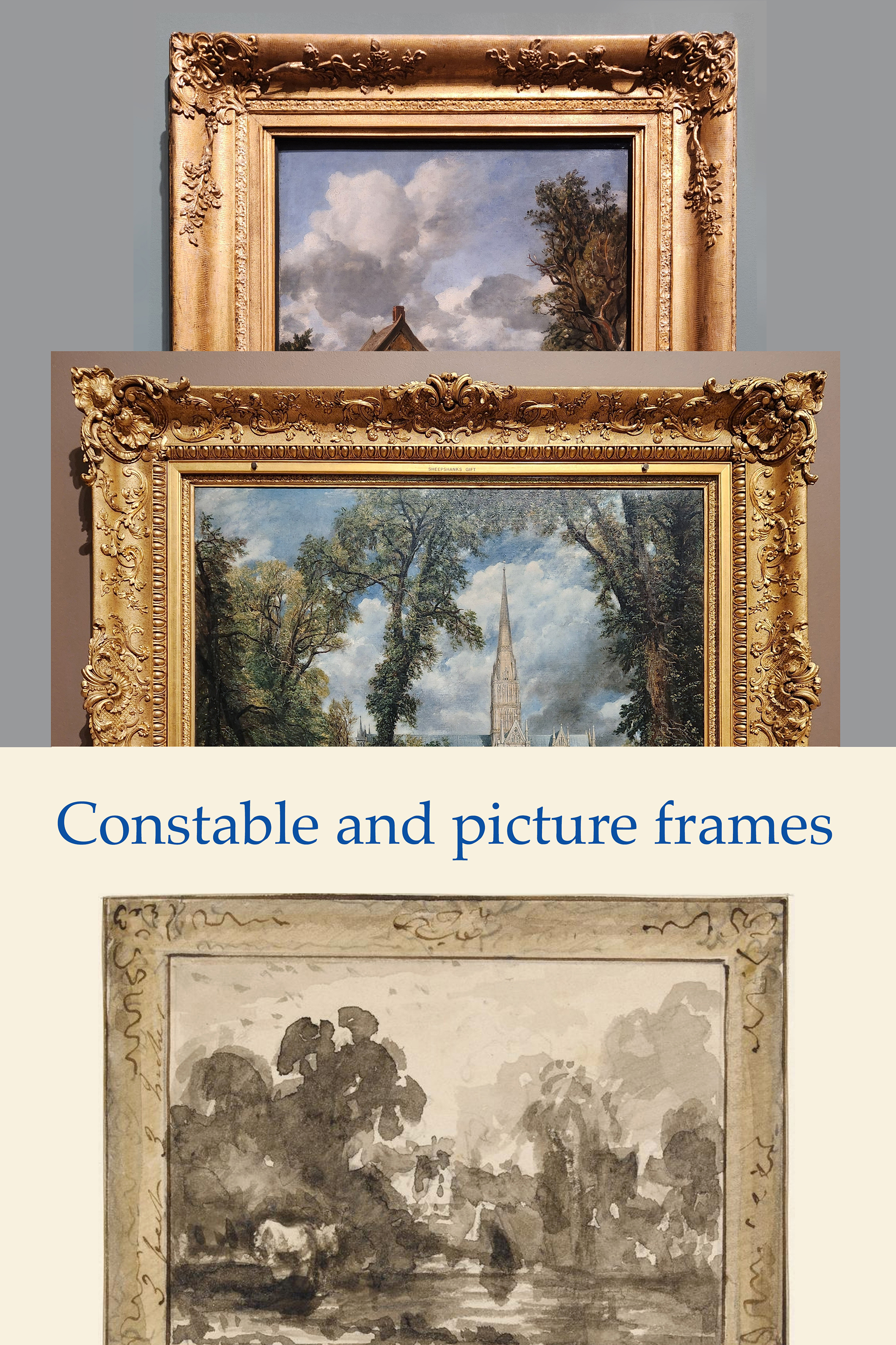

John Constable and picture frames

by Jacob Simon

This is an initial exploration of some of John Constable’s landscape frames, primarily his Royal Academy exhibits, on the occasion of the Tate exhibition, Turner & Constable: rivals & originals (until 12 April 2026) [1]. Here we look at original or early frames and their makers, at attitudes to framing in Constable’s lifetime and at some later reframing.

Constable was a relatively late developer compared with the precocious Turner. He was born in Suffolk in 1776; he first exhibited at the Royal Academy at the age of twenty-five in 1802; he was elected an Associate in 1819 and a full Academician in 1829 at the age of fifty-two. He died in 1837, aged sixty.

In the early 19th century it became fashionable to use richer and wider picture frames, a taste partly driven by the desire of artists exhibiting at the Academy to attract attention to their paintings and to separate them from competing works, but also influenced by the prevailing Regency taste for heavier interiors and furnishings. The results excited comment. In 1822, Robert Hunt, a landscape and portrait painter and a regular critic for The Examiner, singled out Constable’s View on the Stour near Dedham (see below) as a work which

‘…makes us most of all enjoy, among the glare of gold frames and gaudy colours, the consoling recollections of the charms of nature’, noting that ‘This glare is most offensive to good taste. It detracts from the proper graphic effect of the rooms as well as of the individual works.’ [2]

George Scharf (1820-95), Exhibition of the Royal Academy, 1828, ink, watercolour, 18.9 x 26 cm., London Museum

Constable’s frames largely conform to the fashions of his time, although on one occasion he refers somewhat ambiguously to a frame of ‘my own invention’ [3]. His taste in framing is not easy to follow. Unlike Turner’s, very few, if any, of his large-scale paintings are in their original frames [4]. Unlike Thomas Lawrence and some other portrait painters, Constable did not resort to using a limited range of standard patterns [5]. With a portrait painter working to commission, the patron would choose a frame, and pay for it, whether from those on display in the artist’s showroom or by going to their own framemaker. A landscape painter not working to commission, however, needed to choose and pay himself for the frame for a picture to be shown at a public exhibition. Constable sold relatively few of his Academy exhibits and would sometimes repurpose a frame from an unsold picture. As with the works of other much traded artists, his pictures have sometimes been reframed by later owners, including by public institutions in Britain and America.

On one occasion, Constable referred to ‘my book’, when writing to a patron about the cost of his frames [6], although any such a book, probably recording sales and purchases, is lost. However, we do have his journal written for his wife in 1824 and 1825 [7], and many letters survive, documenting his work, and have been published in a series of volumes. Constable used various leading London framemakers: Woodburn, Crouzet, Coward and John Smith, discussed in the Appendix [8].

The four main historic Constable collections are those of the National Gallery, the Tate, the Victoria and Albert Museum (then named the South Kensington Museum) and the Royal Academy, all of which have benefited from Isabel Constable’s gifts and bequests of oil paintings in 1887 and 1888. Other pictures were given or bequeathed by Robert Vernon in 1847, John Sheepshanks in 1857, Henry Vaughan in 1886 and 1900 and George Salting in 1909.

The Valley Farm, exh. 1835, o/c, 147.3 x 125.1 cm., Tate, R35.1; detail showing a removable glazing window with bolt, inserted in the late 19th century

In the later 19th century many frames in London public collections were altered to take glass to protect pictures. The act of inserting a window of this kind usually meant that the sight edge of the frame was altered, set back, obscured or cut away.

Constable’s Academy exhibits and other paintings are explored here chronologically according to frame type: Morland frames, acanthus scotia frames with foliate corners, trailing foliage frames, swept frames, frames with small-scale overall ornament, The haywain, and Constable’s Academy diploma picture. Also discussed are two early reframings and some later reframings. For clarity, ‘R’ numbers are given, referring to Graham Reynolds’s Constable catalogue raisonné [9]. Ornament is in compo unless stated otherwise [10]. Frame reverses have not been examined. All pictures reproduced here are by Constable unless stated. An asterisk * indicates a picture in the 2026 Tate exhibition.

Morland frames

The Morland frame, so-called because it is found on some paintings by the artist George Morland, is characterized by a plain hollow and a reeded top edge (sometimes called ‘fasces’) bound with ribbon at the corners and at spaced-out intervals along the sides. This design was most common in the 1790s and early 1800s.

Dedham Vale from the Coombs, 1802, modern frame, o/c, 43.5 x 34.4 cm., Victoria and Albert Museum, R02.7

Golding Constable’s house, East Bergholt, c.1809-11, modern frame, o/millboard laid on panel, 18.1 x 50.5 cm., Victoria and Albert Museum, R10.28

Examples of Morland frames on Constable’s works include *Dedham Vale from the Coombs, 1802, and Golding Constable’s House, East Bergholt, c.1809-11, both made for the Victoria and Albert Museum by Timothy Newbury in 2003 [11]; also the portraits, Archdeacon John Fisher, exhibited 1817 (Fitzwilliam Museum, R17.3), and The Rev. Dr James Andrew and Mrs James Andrew (Tate, R18.35, R18.36). Like Constable, Turner used Morland frames on occasion but on larger pictures, such as his *Dolbadern Castle, exhibited 1800 (Royal Academy).

The Valley of the Stour, c.1800-9, o/paper laid on canvas, 49.8 x 60.0 cm., Victoria and Albert Museum, R08.57

The Valley of the Stour, c.1800-9, a variant on this style, has modest projecting foliate corners and a cut-out veined leaf sight edge. It was received from Isabel Constable in 1888 ready framed, and so is probably an early or original frame.

Acanthus scotia frames with foliate corners

A common classical pattern in the 1790s, enduring into the new century, was a frame with a deep hollow, sometimes decorated with fluting or, as here, an acanthus motif, and with a top edge frieze of guilloche or florets set between two narrow mouldings.

Trees at Hampstead: the path to church, exh. 1822?, o/c, 91.4 x 72.4 cm., and detail; Victoria and Albert Museum, R22.6

Trees at Hampstead: the path to church was probably exhibited in 1822 as ‘A study of trees from nature’. The frame appears to be original: a deep hollow of cross-cut acanthus-&-fan set between an inner tongue and a narrow top edge floret frieze. The heavy applied projecting foliate corners exemplify a short-lived fashion dating to the early 1800s. Such corners were vulnerable, and they could become unsightly as they aged and attracted dirt.

Trailing foliage frames

We find in the 1810s, if not before, elaborate corner decoration being set within the profile of the frame, in place of projecting corners of the type seen above. Trailing foliage extends from the corners and with larger frames also from the centres.

Sketch for a frame for ‘The white horse’, c.1819, pencil, ink & wash, 10.9 x 14.3 cm., Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, R19.6

The drawing, Sketch for a frame for ‘The white horse’, depicts a frame around a sketch of the composition of Constable’s The white horse. It has been described as intended for a framemaker [12]; however, Constable would usually deal with his framer face-to-face. Rather than being a sketch passed to a framemaker (and then returned to the artist), could it be a quick drawing which Constable used to show a patron the sort of frame that he had in mind? The frame has decorative corners, with centres on the long sides, and short trails of foliage. The canvas size is given as 3ft 3ins by 4ft 6ins. The drawing is usually dated to 1819 when Constable exhibited *The white horse (Frick Collection, see below), a larger painting than is shown here. It is not possible to link the drawing to a particular version of this composition.

A cottage in a cornfield, 1815, 1833, o/c, 62.0 x 51.5 cm.; details showing cuts in the side of the frame; Victoria and Albert Museum, R33.3

Constable, copy after John Hoppner (1758-1810), Lady Louisa Manners, Countess of Dysart, 1823-25, o/c, 74.9 x 62.2 cm., Ham House, NT

A cottage in a cornfield, exhibited 1833 but begun in 1815, appears to be in its original exhibition frame, albeit an old frame cut down to fit [13]. It is almost identical in form and ornament, although not in finish, to that on Constable’s copy of Hoppner’s Countess of Dysart, 1823-25, at Ham House. The main difference is in the ornament next to the sight edge. Note that the 1833 Academy exhibition was the occasion when Constable had a frame on another exhibit, A heath, cut to fit. Ramsay Richard Reinagle, Constable’s former student friend, was hanging the exhibition. It would be best, Reinagle told him, if

‘…the whole side of a room can be made to hang in harmony like a bunch of grapes’. He continued, ‘Frames have been our Sore Enemies’, and he pleaded with Constable, ‘Now my good fellow, pray order another frame’, and lamenting, ‘It is a Mania, that… of overframing pictures; which seems to rage more on our Walls than any where else.’ [14]

Constable immediately sent to his framemaker, who suggested cutting the frame[15]. A few days later he told his fellow Academician, C.R. Leslie, that the Academy’s Council was determined to regulate framing the following year [16]. However, it was not until 1847 that the Academy offered formal advice on the framing of paintings [17].

Swept frames

There was a revival in interest in French styles in Britain in the early 19th century. As the artist and illustrator, W.H. Pine, put it in 1819,

‘It is equally due to the artists of France to acknowledge that their elegant fancy furnished the English frame-makers with examples for tasteful and gorgeous patterns…’ [18]

The ledgers of the leading framemaker, John Smith, show that the Rococo taste was coming back into fashion in the 1810s. He began supplying ‘sweep sided’ frames to customers as early as 1812 [19].

As for Constable, it would seem that he chose swept frames for some of his smaller framed landscapes. These are difficult to document. Although exhibited in the 1810s, could one or more of the frames discussed here be later, perhaps dating to the 1830s? Note the comparison below with a frame on a work by David Wilkie. Three frames in the Victoria and Albert Museum are illustrated here, two with a Sheepshanks provenance and one long in the family. They were restored some time ago to give them their present uniform bright appearance.

Summer evening: view near East Bergholt, c.1811-12, exh. 1812?, o/c, 31.7 x 49.5 cm., and detail, Victoria and Albert Museum, R12.2

Summer evening: view near East Bergholt was given to the museum by Isabel Constable in 1888. *Boat building near Flatford Mill, exhibited 1815, and Hampstead Heath: The Vale of Health, exhibited 1821, 1822 or 1827, were given to the museum by the art collector, John Sheepshanks (1787-1863), as part of his larger gift in 1857. Their frames differ from those on other pictures in his gift.

Boat building near Flatford Mill, exh. 1815, o/c, 50.8 x 61.6 cm., and detail, Victoria and Albert Museum, R15.2

Hampstead Heath: The Vale of Health, c.1819-21, o/c, 53.3 x 77.6 cm., and detail, Victoria and Albert Museum, R21.10

Top: Constable, The Vale of Health; bottom: David Wilkie (1785-1841), Irish Whiskey Still, 1840, o/panel, 119.4 x 158.0 cm., National Gallery of Scotland

Wilkie’s painting, above, has a frame larger in size than that on Constable’s Vale of Health, but it is comparable in detail, including the swept S-scrolls on both the back and top edges.

Frames with small-scale overall ornament

By the 1820s Constable was using ‘rich & heavy’ frames, as he described them to one patron [20]. Such frames feature an abundance of ornament. As Thomas Lawrence wrote in 1828,

‘A good frame… should be sufficiently broad and rich, but the ornament of that richness composed throughout of small parts, and usually it should be unburnished.’ [21]

Three frames in the Victoria and Albert Museum stand out, not least for their present uniform bright appearance after restoration. They are clearly exhibition frames from the 1820s.

Dedham Lock and Mill, 1820, o/c, 53.7 x 76.2 cm., Victoria and Albert Museum, R20.10

Hampstead Heath: Branch Hill Pond, exh. 1828, o/c, 59.6 x 77.6 cm., Victoria and Albert Museum, R28.2

Dedham Lock and Mill, signed and dated 1820, and Hampstead Heath: Branch Hill Pond, exhibited 1828, are housed in near identical original or early frames, with foliage and strapwork on the cross-hatched ogee sides and corner-&-centre shells, the inner edges altered by the insertion of a glazing window.

Top, Dedham Lock and Mill, and bottom, Hampstead Heath: Branch Hill Pond, details

The foliage and strapwork on these two frames are very similar to the ornament on the frame of William Daniell’s The Hirkarrah camel (Sir John Soane’s Museum) of 1832. That in itself does not mean that Daniell’s frame was produced by the same maker; we know from the ledgers of the composition ornament maker, George Jackson, that he supplied numerous London framemakers with stock ornament [22].

Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s grounds, exh. 1823, o/c, 87.6 x 111.8 cm., Victoria and Albert Museum, R23.1

*Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds, exhibited 1823, was painted for Constable’s friend, John Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, and retains what is probably its original frame. The shell centres and the running ornament of scrolling leaves are closely similar to Thomas Lawrence’s influential portrait frames of the 1810s, although with a cross-hatched rather than a punched ground. A similar frame to Constable’s, including the inner egg-&-dart, can be found on Henry Fuseli’s Friar Puck, 1819 (Tabley House, Cheshire).

Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s grounds, details

Bishop Fisher directed Constable to use Smith of Kensington (see appendix) – apparently George Smith – for framing this picture [23]; when it returned from exhibition at the Academy, Constable noted of the frame, ‘wood much injured at the Exhibition’ and he toyed with the idea of swapping it for another frame, although this did not happen.

The haywain

The haywain, exh. 1821, frame 1821 or 1838, o/c, 130.2 x 185.4 cm., and detail, National Gallery, R21.1

The haywain, exhibited in 1821, has a wide, richly ornamented corner-&-centre frame, ogee in section, with an elaborate running pattern of small-scale looping foliage on a cross-hatched ground.

The haywain, with casts of Constable’s medal from the Salon

Modern impressions of the gold medal – which Constable was awarded when the painting was shown at the Paris Salon in 1824 [24] – were inset in the frame at a later date.

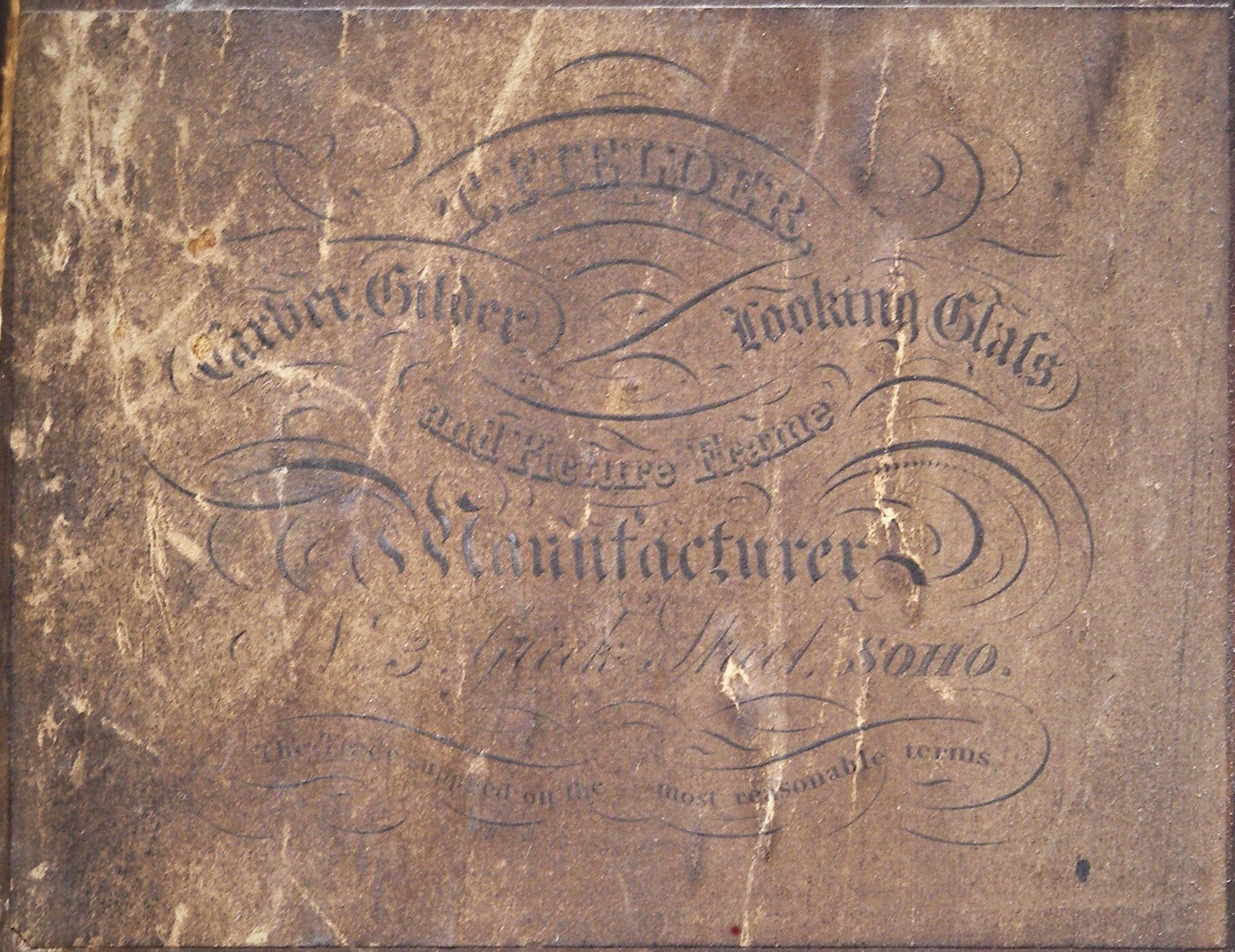

Label of Thomas Fielder from reverse of frame

The haywain spent fourteen years or so in France, in the collection of a M. Boursault, whose collection was bought for the owner of Saltmarshe Castle, Herefordshire, in 1838. It was eventually given to the Gallery by Henry Vaughan in 1886. The reverse bears three labels, one relating to Vaughan; another that of Thomas Fielder (c.1793-1854), a Soho carver and gilder, looking glass and picture framemaker, with his address on the label given as 3 Greek Street, premises that he occupied from about 1831 until 1854; and a third partial manuscript label, with part of a word, ‘Dor…’, prominent; the rest of the wording is not legible.

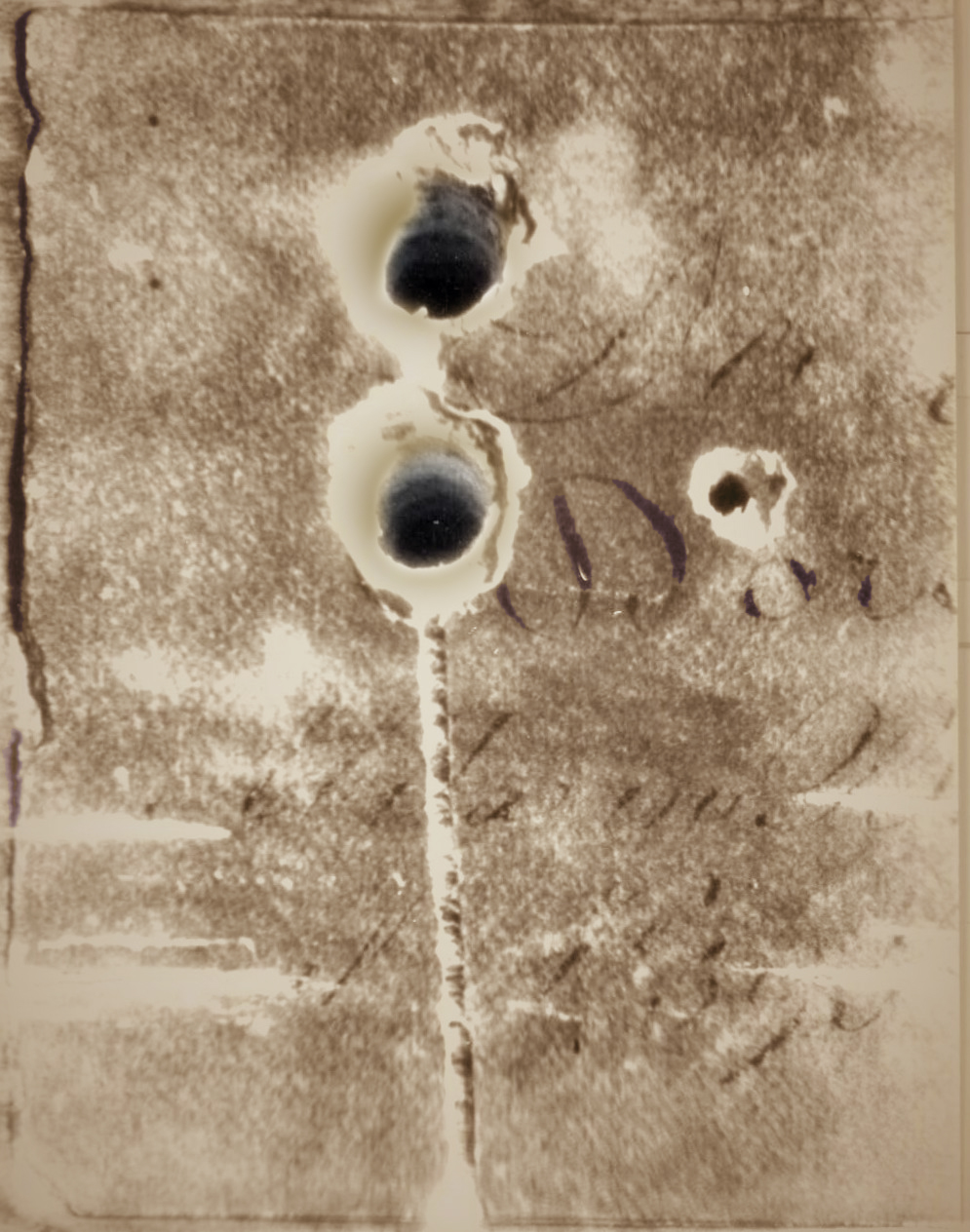

Label, possibly of a French doreur, from reverse of frame

There are three scenarios to consider:

1) The frame is original and thus English, dating to 1821: although it would be unusual to find a frame with this type of ornamentation so early.

2) The frame is French, given that the label reading ‘Dor…’ is perhaps the start of the word ‘Doreur’, or gilder: however, comparable French frames dating to the 1820s remain to be identified, and the frame is reportedly made using English composition, making this scenario unlikely [25].

3) The painting was reframed by Thomas Fielder on its return from France in 1838, rather than, say, an earlier frame being repaired by him: the style of the frame seems in keeping with this date.

Constable’s Academy diploma picture

A boat passing a lock, 1826, exh. 1829, o/c, 101.6 x 127.0 cm., and detail, Royal Academy of Arts, R26.15

*A boat passing a lock, 1826 (Royal Academy), is a version of Constable’s earlier The lock (see below). It was exhibited at the British Institution in 1829 and became Constable’s diploma picture, given to the Academy following his election as a Royal Academician in 1829. The frame has a deep stepped profile and five orders of decoration. The small shell corners, with C-scrolls and foliage, are joined by a flattened running bead.

The frame is a puzzle. It is different from those on Constable’s works of the time and indeed from those of other artists. Is it a frame of ‘my own invention’, as Constable described another frame in 1823? We lack evidence. Could it have been chosen by its first owner, the bookseller, James Carpenter, who claimed that the frame was his own property when Constable bought the picture back from him three years later? [26] Again, we lack evidence. Could the frame have been swapped with another of the same standard 50 x 40 ins size at the Academy? This seems unlikely, given the Academy’s conservative approach to framing. The frame is attributed on the Academy’s database to one of Constable’s framemakers, Samuel and Allen Woodburn, but in the absence of documentation this is very uncertain. The frame served as a model for the Tate when reframing *Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, exhibited 1831 (Tate, R31.1), following its acquisition in 2013 [27].

Two early reframings

Two important paintings by Constable were reframed by their new owners during the artist’s lifetime, both using their own framemaker: James Morrison employing George Morant & Son in 1834, and Robert Vernon apparently looking to William Thomas in 1835.

James Morrison (1789-1857) purchased The lock on the opening day of the Academy exhibition in 1824, together with its frame. However, ten years later when setting up a gallery for his collection in Harley Street he decided to reframe the picture, using the services of his architect, John Buonarotti Papworth.[28] In a draft letter to Morrison, Constable wrote,

‘I was glad to hear you express a desire to put my picture into a handsome frame. I believe Mr. Papworth has ordered one but of what kind or of whom, I know not. I shall be ready to take the old one at a valuation.’ [29]

The lock, exh. 1824, framed 1834, o/c, 142.2 x 120.7 cm., Private coll., R24.1: Christie’s, 12 June 2012, Lot 37

Morrison’s usual framemaker was the interior decorator, George Morant, who incidentally was for a time the owner of the first version of Constable’s The Glebe Farm (R27.7?). Morrison’s frame is probably the bold French Regence-revival pattern in which the painting was sold at auction in 1990 and 2012. It is not as heavy as the frames found on Morrison’s Old Masters such as Nicolas Poussin’s The Triumph of Pan or (before the recent reframing) on Rembrandt’s Hendrickje Stoffels, both now in the National Gallery.

Stoke-by-Nayland, c.1835-37, o/c, 126 x 169 cm., Art Institute of Chicago, R36.19

Coincidentally or not, it is to the same pattern as the frame on Constable’s slightly larger painting, * Stoke-by-Nayland, a frame catalogued as possibly French, second half of the 19th century (repr. R.B. Brettell and S. Starling, The art of the edge: European frames 1300-1900, 1986, p. 104).

Robert Vernon (1774-1849) chose to have The Valley Farm, exhibited 1835, reframed on acquisition. In September 1835, following the close of the Academy exhibition, Constable told his friend, the artist Charles Robert Leslie, that Vernon had paid him for the picture and had it on display. But apparently it was without its Academy frame since Constable added,

‘Still I must compete with my friends in the collection with my picture in the worst light in the house and without a frame…’.[30]

How the picture was then reframed, seemingly by William Thomas (c.1792-1864), is not known [31]. The picture formed part of Vernon’s gift to the National Gallery in 1847. In 1878 Isabel Constable, the artist’s daughter, wrote to the Gallery, saying that she wished to purchase a frame for the Gallery for this painting, as she was

‘…desirous it should be a copy of the frame of ‘The Cornfield’ by J Constable RA’,

but this offer was declined.[32]

The Valley Farm, exh. 1835, o/c, 147.3 x 125.1 cm., Tate, R35.1

The current fluted frame on The Valley Farm appears to have been fitted to the picture subsequently, perhaps in the late 1880s. It has an inserted glazing window. The frame is similar to that on Flatford Mill and on other pictures bequeathed by Isabel Constable (see below). It is unlike Vernon’s, or indeed Constable’s, other frames.

Later framing: Isabel Constable and Charles Golding Constable

Isabel Constable (1822-88) made various gifts and bequests at the wish of herself and her sister and brother. She passed some finished paintings to the National Gallery, several oil sketches to the Royal Academy and numerous sketches and drawings to the South Kensington Museum, now the Victoria and Albert Museum [33]. Some of the finished works were framed in her father’s lifetime, including The cottage in a cornfield (see above). Others were framed subsequently by the family, as for instance in 1865 when Isabel’s brother, Charles Golding Constable (1821-76), sent a number of items to the dealer Joseph Hogarth for framing and other work (perhaps including Gillingham Mill, Victoria and Albert Museum) [34]. Isabel wrote to the South Kensington Museum in December 1887 concerning the landscape sketches in her gift, regretting that

‘…they are not in frames as they would look so much better, but I should like to give the frames to make them complete.’ [35]

In fact, seventeen of the ninety-two paintings, mainly oil sketches, were recorded as already framed on their arrival at the museum (but most are no longer so framed). As to her gifts of six paintings to the National Gallery in 1887 and 1888, we know that the Gallery’s then framemakers, Reginald Dolman & Son, collected certain works from her and were in touch with her directly in 1887 [36].

Flatford Mill, exh. 1817, o/c, 101.6 x 127.0 cm., and detail, Tate, R17.1

*Flatford Mill, exhibited in 1817, formed part of Isabel Constable’s bequest to the National Gallery in 1888. It has a fluted frame, possibly dating to the time of her bequest, with an inserted glazing window. The frame is very similar in detail to those on *Hampstead Heath with a rainbow, 1836 (Tate, R36.7) and *The Glebe Farm, c.1830, exhibited 1835 (Tate, R27.8), both part of her bequest to the National Gallery; also to that on The Valley Farm (above). These frames may have been made by Dolman & Son for the Gallery soon after the arrival of the bequest in September 1888.

Fluted frames had largely gone out of fashion by the 1810s but saw a revival later in the century; to give an example of this revival, in 1859 W. & P. Evans billed the 4th Marquess of Hertford for supplying seventy-five fluted frames, many still on paintings in the Wallace Collection. Of the dozen landscape oil sketches which Isabel gave to the Royal Academy in 1888, eight have fluted frames with an inlay, and probably date to the time of her donation; they are illustrated on the Academy’s website.

Mention should also be made of two other pictures with fluted frames. The cenotaph to the memory of Sir Joshua Reynolds, exhibited 1836 (National Gallery, R36.1), was bequeathed to the Gallery by Isabel Constable. Its fluted frame, a reframing, is a shadow of its former self, lacking acanthus leaves at the corners and decoration on the top edge [37]. *Dedham Vale, exhibited 1828 (National Gallery of Scotland, R28.1), was reframed in the 1980s, a little like that on Trees at Hampstead: The path to church (see above), but without the applied corners and with quite a different sight edge [38].

Later framing: pictures owned by Henry Vaughan and George Salting

The leaping horse, 1824-25, o/c, 129.4 x 188.0 cm., Victoria and Albert Museum, R25.2

Two of Constable’s full-size sketches, The haywain and The leaping horse (Victoria and Albert Museum) were lent to the South Kensington Museum by the collector, Henry Vaughan (1809-99) in 1862 and bequeathed in 1900.

The leaping horse, detail

Both have cross-hatched ogee mouldings, plain but for the corners with vaguely French scrolls, buds and foliage. The frames may date from the period between 1838, when in the care of C.R. Leslie, and the 1850s, before acquisition by Vaughan. They were framed relatively simply and inexpensively, perhaps reflecting the perception of such sketches at the time. Vaughan owned other pictures by Constable, including the finished version of The haywain, which he gave to the National Gallery in 1886 (see above).

George Salting (1835-1909), a wide ranging collector, bequeathed his art collection to the nation, and the National Gallery selected fifteen small paintings by Constable from a larger group of some twenty-eight works. Salting used Henry Critchfield for framing work, 1874-80, and F.C. Buck, 1882-1909; also going to John & William Vokins, although not necessarily for frames [39].

Later framing: other English and American collections

Several large Constable landscapes were framed or reframed when they changed hands in the late 19th or early 20th century. Their framing is quite varied, for larger landscapes sometimes tending to bold swept frames, deriving from the French Rococo style, and for smaller pictures corner-&-centre frames with more of a English character.

In English collections, in order first exhibited: *Stratford Mill (National Gallery, R20.1), exhibited 1820, has a carved Carlo Maratta frame of uncertain date.

The leaping horse, 1825, o/c, 142 x 187.3 cm., Royal Academy, R25.1

*The leaping horse, exhibited in1825, is described on the Academy’s database as having a Louis XIII revival frame featuring a ‘centred & ribbon-bound garland of oak leaves & acorns’, in the form of a torus. In the current article it is considered to be later than the painting, dating to around the time that the picture was donated to the Academy in 1889, given the taste for such ‘cushion’ frames at the period [40].

Chain Pier, Brighton, 1826-27, o/c, 127 x 182.9 cm., Tate, R27.1

*Chain Pier, Brighton, exhibited 1827, has an early 20th century ‘Duveen’ frame, almost certainly made in Paris, an example of the Duveen ‘second type’, so called in an analysis by Nicholas Penny and Karen Serres [41]. This pattern was perhaps first used in 1910; it was described within Joseph Duveen’s firm as the ‘Pinkie pattern’ , after that used for Thomas Lawrence’s Sarah Barrett Moulton (‘Pinkie’) in the Huntington Art Museum.

The full-size *Sketch for Hadleigh Castle (Tate, R29.2) has been reframed at Tate, in an ogee moulding with narrow inner sanded frieze, tooth sight edge and small leaf-and-scroll corners. The profile matches the picture’s earlier, but not original, carved frame, seemingly French mid-18th century, which could not safely be restored [42].

The opening of Waterloo Bridge, exh. 1832, o/c, 130.8 x 218 cm., Tate, R32.1

*The Opening of Waterloo Bridge (Tate, R32.1), exhibited in 1832, has an English carved corner-&-centre frame, probably dating to the second quarter of the 18th century. It may originally have been a full-length portrait frame, turned on its side and tightened to fit the picture.

The white horse, 1819, o/c, 131.4 x 188.3 cm., Frick Collection, R19.1

In American collections, in order first exhibited: *The white horse in the Frick Collection, exhibited in 1819, was Constable’s first large ‘six-footer’. The present frame in the Rococo style perhaps dates to the time of the picture’s sale by Agnew’s to J. Pierpont Morgan in 1894; it was on the picture by 1909 [43].

View on the Stour near Dedham, 1822, o/c, 129.5 x 188 cm., The Huntington Art Museum, R22.1

* The View on the Stour near Dedham in The Huntington, exhibited in 1822, has a 20th century, possibly American, frame with long ribbon-tied reeded sweeps, panels of rocailles, fronds and large-scale corners-&-centres.

Hadleigh Castle, the mouth of the Thames, 1829, o/c, 121.9 x 164.5 cm., Yale Center for British Art, R29.1

*Hadleigh Castle, exhibited in 1829, has a stripped, wide but shallow moulding, ornamented with small leafy fronds, scrolls and rocailles at the corners and centres. It is difficult to place. It has been altered at two corners (see image of frame reverse on the collection website).

Appendix: Constable’s framemakers

Constable used several leading London framemakers, all of whom worked for other Academicians and for significant patrons [44]. We do not know of his framemakers before 1818.

Constable was on friendly terms with the Woodburn brothers, a leading dealing and framing business. He had one of his paintings on sale through the business in 1818, as we find from a letter from Allen Woodburn to the artist [45]. He is documented as using Woodburn for some picture framing and perhaps for other services between 1821 and 1831. On 10 September 1825 Constable noted in his journal,

‘I called on Mr. Woodburn – found my frame bill £65 which was more than I expected, but it was all right’, and on 24 November he recorded, ‘I dined with Allen Woodburn in St. Martin’s Lane’, adding on 6 December, ‘Two Mr. Woodburns called – Allen & Samuel ….’.[46]

There is a payment of £50 in Constable’s bank account to Woodburn on 3 September 1831 [47]. Later, in 1835, Samuel Woodburn employed Constable as an expert witness in a court case [48].

In 1822 one of Constable’s most important patrons, John Fisher, Bishop of Salisbury, directed him to use the Smiths, father and son, for framing his order; – framemakers whom Constable came to categorise as ‘the wretched Smiths’, describing the son as a ‘wretched lying young rascal’. Fisher had first used ‘old Smith’ for framing Constable’s works in 1817, and later in 1822 told the artist that father and son had set up shop together in Kensington very near the Palace [49]. In exasperation at their inability to complete an order, Fisher was reduced to asking Constable to buy gold leaf for Smith in 1823 and even ‘to pay the Ornament maker his two Pounds’.[50]

In December 1825 Constable compared the work of three framemakers whom he had been using.

‘Cruzac’, he wrote in his journal, ‘works much cheaper than Coward – but not so fine & finished as Smith.’ [51]

‘Cruzac’ appears to be a misreading for Joseph Crouzet, who worked for other Academicians and at Windsor Castle. Bishop Fisher complained to Constable in 1825 about ‘your little French Frame Maker’, probably Crouzet.[52] Coward is probably John Coward.

‘At breakfast Mr. Coward called to measure a frame’, Constable noted in 1824.

Coward died in September 1826.

Smith must be John Smith, mentioned above, who sold Constable a

‘…Church piece… by E. de Witt’ for £50 in 1831, including ‘a handsome 5 ins Moulding gilt frame with corners & scrolls, raking leaf, egg & French mouldings…’,

together with a small carved French frame for £2.12s. [53]. Smith framed work for Constable and for his friend, C.R. Leslie, in the 1830s [54].

Constable also employed Nathaniel Castile to frame David Lucas’s prints of his work in 1834, with further payments due in 1836 [55].

****************************

[1] With thanks to Zoe Allen and Jenny Gaschke at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Christopher H. Brooks at the Art Institute of Chicago, Emma John and Keith Morrison at the National Galleries of Scotland, Isabella Kocum at the National Gallery, Pascal Labreuche at the Guide Labreuche, Adrian Moore at Tate and Lynn Roberts at The Frame Blog for their help. Online collection databases are problematic but can be helpful, especially those of the Yale Center for British Art, the Royal Academy and Sir John Soane’s Museum, and also those of the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Gallery and the National Trust

[2] Judy Crosby Ivy, Constable and the Critics 1802-1837, 1991, p. 95

[3] R.B. Beckett (ed.), John Constable’s Correspondence: VI The Fishers, Suffolk Records Society, vol. 12, 1968, p. 127

[4] For Turner, see The Frame Blog, ‘Turner’s Picture Frames: Part 1’ and subsequent parts

[5] For Lawrence, see Jacob Simon, ‘Thomas Lawrence and picture framing’, on the National Portrait Gallery website

[6] Letter to Henry Hebbert, 19 November 1828, see R.B. Beckett (ed.), John Constable’s Correspondence: IV Patrons, Dealers and Fellow Artists, Suffolk Records Society, vol. 10, 1966, p. 102

[7] R.B. Beckett (ed.), John Constable’s Correspondence: II Early Friends and Maria Bicknell (Mrs Constable), Suffolk Records Society, vol. 4, 1964, pp. 313-431

[8] For detailed information on these framemakers, see Jacob Simon, ‘British picture framemakers, 1600-1950’, on the National Portrait Gallery website

[9] Graham Reynolds, The Early Paintings and Drawings of John Constable, 1996, and The Later Paintings and Drawings of John Constable, 1984

[10] Compo, short for composition: a pliable mixture, usually made of whiting, glue, resin and linseed oil, pressed to make moulded ornament

[11] Golding Constable’s house, East Bergholt was one of the small oils received by the South Kensington Museum in 1888 already framed, but whether this frame survives has yet to be established

[12] Reg Gadney, John Constable R.A. 1776-1837: A Catalogue of Drawings and Watercolours… in the Fitzwilliam Museum, 1975, no. 25.

[13] The frame was ‘restored, regilded and refitted’ at the Museum in 1913 (information from Zoe Allen)

[14] Leslie Parris et al. (eds), John Constable: Further Documents and Correspondence, 1975, p. 274

[15] R.B. Beckett (ed.), John Constable’s Correspondence, III The Correspondence with C.R. Leslie, R.A., Suffolk Records Society, vol. 8, 1965, p. 221

[16] Ibid., p. 102

[17] Jacob Simon, The Art of the Picture Frame: Artists, Patrons and the Framing of Portraits in Britain, 1996, p. 20

[18] W.H. Pyne, The History of Royal Residences, vol. 2, 1819, p. 83

[19] Simon 1996, cited in note 17, p. 70

[20] Correspondence, IV, cited in note 6, p. 98

[21] Simon 1996, cited in note 17, p. 102

[22] For a fuller discussion, see Jacob Simon, ‘British picture framemakers, 1600-1950’: George Jackson

[23] Correspondence, VI, cited in note 3, p. 102

[24] The frame was subsequently altered to accommodate glass, as can be seen in Claus Grimm, The Book of Picture Frames, 1981, p. 272; the sight edge is thus a replacement, see National Gallery Report 1982-84, p. 44. The inset impressions of the gold medal were fitted in 1927, following acquisition by the Gallery of the gold medal itself, and renewed in 2024. With thanks to Isabella Kocum for information and ideas

[25] Isabella Kocum writes, ‘From a trade’s perspective, the frame is made using English composition, which is characteristically darker in colour. The recipe differs from the French composition, which is typically whiter. Early English composition is relatively light in tone, but over time the recipe changed: it became more umber in colour due to its ingredients, making it increasingly brittle and prone to cracking. This is evident on the Haywain frame, which uses a later composition recipe and shows losses caused by cracking. The frame is oil gilded, a technique more commonly associated with northern countries such as England and the Netherlands, whereas French gilding was predominantly water gilded.’ (email communication, 20 January 2026)

[26] See Reynolds, Later Paintings, cited in note 9, under no. 30.1.

[27] For the reframing, in place of what may have been an 18th-century rococo swept frame altered in the mid-19th century, see Adrian Moore, ‘The framing of John Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows’, Tate Papers, no.33, 2020

[28] Caroline Dakers, A Genius for Money: Business, Art and the Morrisons, 2011, pp. 54, 110n35.

[29] Correspondence, IV, cited in note 6, p. 130.

[30] Correspondence, III, cited in note 15, p. 131

[31] Draft letter from Constable to Vernon, see Correspondence IV, cited in note 6, pp. 122, 133

[32] National Gallery archive, NG3/327/1, and NG6/5/692. In an article by Susanna Avery-Quash with Christine Riding, ‘Two hundred years of women benefactors at the National Gallery: an exercise in mapping uncharted territory’, n.d. but c.2024, this reference to Isabel Constable wishing to purchase a frame is confusingly associated with another painting by Constable, The cenotaph to the memory of Sir Joshua Reynolds

[33] Ian Fleming-Williams and Leslie Parris, The Discovery of Constable, 1984, pp. 85-86

[34] Ibid., p. 71

[35] Mark Evans, Clare Richardson & Nicola Costaras, ‘A recently discovered oil-sketch by John Constable at the Victoria and Albert Museum’, Burlington Magazine, vol. 155, 2013, p. 823

[36] National Gallery archive, NG6/13/18

[37] Additionally, in note 124 of the article cited in note 32, the history of framing The Cenotaph is set out: It ‘is now back in the frame it came in – a typical English nineteenth-century frame (fluted hollow) based on a French model. The painting can be associated with two other frames: (i) a French centre corner frame, which was on the picture before it was put back into the English frame, and (ii) a Carlo Maratta type frame, popular in England during the nineteenth century, which was cut to fit the painting at some unknown date.’ Frame (i) above was purchased from Georges Bac for Gainsborough’s Mrs Siddons in 1966 and transferred to Constable’s painting in 1986, at which point it was heavily adjusted (information from Isabella Kocum). This history demonstrates the intricacies in tracing Constable’s frames

[38] Information from Emma John and Keith Morrison. An earlier frame remains in store

[39] Guildhall Library, London, Salting papers, MSS 19742, 19747

[40] Simon 1996, cited in note 17, p. 178

[41] Nicholas Penny and Karen Serres, ‘Duveen’s French frames for British pictures’, Burlington Magazine, vol. 151, 2009, p. 390. The ‘Pinkie’ frame is reproduced in Simon 1996, cited in note 17, p. 24. See also Gerry Alabone, ‘The picture frame: knowing its place’, in Art, Conservation and Authenticities: Material, Concept, Context, eds E. Hermens and T. Fiske, 2009, pp. 64-65

[42] Information from Adrian Moore

[43] The picture was in its present frame by 1909, see Gadney 1975, cited in note 12, no. 25. See also William Kentridge and Aimee Ng, Constable’s White Horse, New York, 2020, pp. 56-57

[44] For detailed information on these framemakers, see Jacob Simon, ‘British picture framemakers, 1600-1950’

[45] Correspondence, VI, cited in note 3, p. 165

[46] Correspondence, II, cited in note 7, pp. 390, 412, 417

[47] Correspondence, IV, cited in note 6, p. 167

[48] Ibid., p. 168

[49] Correspondence, VI, cited in note 3, p. 102

[50] Ibid., p. 127

[51] Correspondence, II, cited in note 7, p. 417

[52] Correspondence, VI, cited in note 3, p. 195

[53] Victoria and Albert Museum, National Art Library, Smith day book, vol. 2, p. 256

[54] Simon 1996, cited in note 17, pp. 88, 90

[55] Correspondence, IV, cited in note 6, pp. 451-52