Framing the European paintings at The Metropolitan Museum: Part 3

by Keith Christiansen

FRAMES BEFORE THE AGE OF FRAMES: the 14th to the 16th century, focusing on Italy

Between 1508 and 1510, on the vault of the choir of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, Bernardino Pinturicchio depicted the four Evangelists, viewed through feigned marble oculi.

Pinturicchio (1454-1513), St Luke painting the Virgin, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

St Luke, the patron of painters, is shown at work on an image of the Madonna and Child, adding the finishing touches of blue – undoubtedly an expensive lapis lazuli – from a ceramic bowl he holds in his left hand. The panel on which he paints has already been framed and gilded, its top adorned with a semi-circular lunette and palmette (acroterion), reflecting the Renaissance obsession with the vocabulary of classical architecture.

Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1532-1625), Self-portrait at an easel, 1556, o/c, 66 x 57 cm., Łańcut Castle Museum, Poland

Fifty years or so later the Cremonese painter Sofonisba Anguissola depicted herself at her easel, painting a picture on the same theme. It has no frame. Between these two dates, the frame assumed its place throughout Europe as an object designed and crafted independently of the picture it might hold, its appearance reflecting the dynamics of the market and the taste of a patron as much as the decision of the artist – the dominant story traced in the two previous essays through examples in The Metropolitan Museum.

Gothic and transitional frames

In the period under examination in this essay, both north and south of the Alps, the design of frames preceded and often conditioned the appearance of the paintings for which they were made. This was as true for modest-sized panels created for either public and private devotion as it was for portraits. But the most complex examples are those large, multi-panel altarpieces which resulted from the unique collaboration of painter and carver, the latter of whom was responsible for crafting the constituent parts and delivering them to the artist with some or all of their framing elements already attached. North of the Alps, those altarpieces were likely to consist of a central unit which might be either painted or sculpted and a series of individually hinged panels painted on both the front and back sides so that they could be opened and closed, concealing or revealing the central image in accordance with liturgical requirements.

Master of St Augustine (fl. late 15th century), Scenes from the life of St Augustine of Hippo, c.1490, o/panel, 137.8 x 149.9 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

A representative example is depicted on a panel which once formed the centre of just such an altarpiece. It shows the great 4th century Church father, St Augustine, being consecrated as bishop of Hippo. According to reigning pictorial conventions, the artist has set the event in a Gothic church of his own time, with Augustine seated before a multi-winged altarpiece crowned by a Gothic shrine, itself having folding wings to enclose the polychrome statue of the Virgin and Child.

Rogier van der Weyden (workshop; c.1399-1464), The Nativity Polyptych, c.1450-60, o/panel, overall dimensions 151.8 x 274.3 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Unfortunately, The Met’s panel lacks both its hinged wings, of which two fragments survive, as well as its original frame, but an example remarkably close in its configuration to the one depicted is the Nativity Altarpiece from the workshop of Rogier van der Weyden, which lacks only its two outermost wings.

Contrasting with this northern tradition, in Italy and Spain large and often multistoreyed polyptychs were fixed constructions.

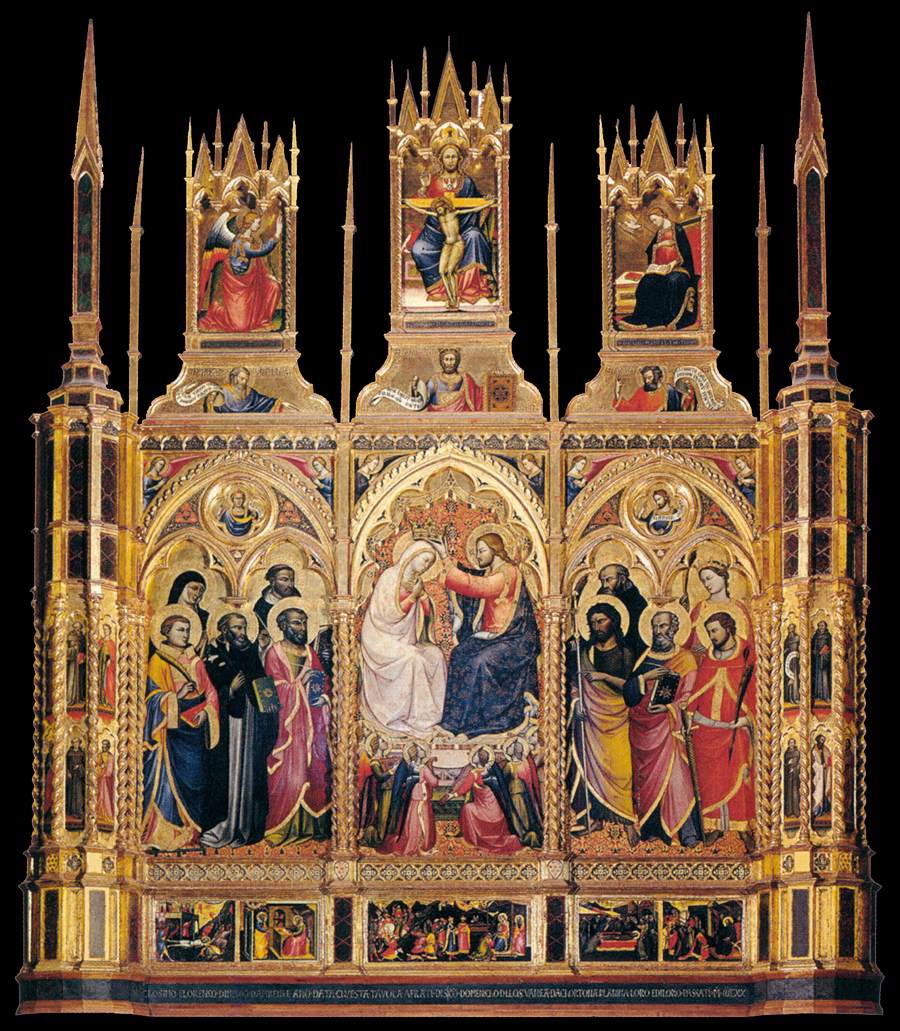

Giovanni di Tano Fei (fl.1384-1405), Coronation of the Virgin with saints, 1394, tempera/panel, 199.1 x 193 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

A relatively modest example in The Met is the Gothic polyptych which the unremarkable Giovanni di Tano Fei painted in 1394 for Alderotto Brunelleschi’s chapel in the church of San Leo in Florence. It consists of three large panels with attached framing elements and a box-like base, or predella. Each of the main panels, with their built-out gables, would have been delivered to the artist from a workshop specializing in woodwork and carpentry. Once gilded and painted, they would have been transported to the church for assembly with a system of dowels and battens, and applied colonets which were set in place both to mask the joins between the panels and to function as visual supports for the projecting frame elements. The frame gave the polyptych its architectural integrity and employed many of the same features found on the portals of Gothic churches.

Giovanni Fei, Coronation of the Virgin with saints, detail of predella panel

In addition to its architectural aspect, the frame also provided a place where the artist might indicate the name of the various saints depicted as well as record his name and/or that of the patron(s), the date the work was completed or the chapel dedicated, and perhaps even include a commemorative inscription or invocation. The inscription below the center panel of Fei’s altarpiece translates as,

‘Alderottus Brunelleschi had this altarpiece made with what his paternal uncle Silvester left for the redemption of his soul and the souls of his family in the year of our Lord 1394’.

In the predella Fei also depicted both the patron and his deceased uncle, who are shown kneeling, their gaze directed to the principal scene where Christ places a crown on the Madonna’s head.

What Giovanni Fei’s polyptych looked like in the simple, beamed-ceiling interior of the church of San Leo in the very centre of Florence can only be guessed at, for the church was secularized in 1785, converted into a residential building, and destroyed in 1901. Removed from its deconsecrated religious setting, the altarpiece began its peregrinations through a series of private collections, first in Florence and then Avignon, which makes its relatively intact survival all the more remarkable.

Yet even when an altarpiece remained in situ, its frame securely attached to the painted panels, there was no guarantee that it would escape the vagaries of taste. Already by the mid-15th century the fashion in Florence for elaborate Gothic altarpieces had yielded to the triumphant, all’antica style of the Renaissance, whereby a single, square or rectangular panel (the quadro) with a unified picture field was adorned with a frame incorporating pilasters or columns and an entablature derived from classical Roman architecture.

Lorenzo di Martino, Coronation of the Virgin, 1402, tempera/panel, 208 x 261 cm., San Domenico, Cortona. Photo: Web Gallery of Art

Many Gothic altarpieces were considered old-fashioned by this point, and were replaced by something more up-to-date. In 1438, Cosimo de’ Medici had the enormous multi-storeyed Gothic polyptych then on the main altar of the Convent of San Marco in Florence removed and sent to a sister institution in Cortona, where it can still be seen today. As part of a general redesign of the conventual church under the direction of Michelozzo di Bartolomeo, Cosimo then commissioned a new altarpiece in the all’antica style from Fra Angelico (its frame may well have been designed by Michelozzo, whose architectural style is reflected in the throne of the Virgin). In turn, that altarpiece was replaced in the 17th century, its frame eventually discarded and its predella cut up and sold (the individual scenes of the predella are today dispersed among five different museums).

Taddeo Gaddi (fl.1334-d.1366), Madonna & Child enthroned, with saints, c.1340; updated c.1480, tempera/panel, 109.9 x 228.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Taddeo Gaddi (fl.1334-d.1366), Madonna & Child enthroned, with saints, c.1340; updated c.1480, tempera/panel, 109.9 x 228.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

An alternative solution to replacement was to change the frame of an outmoded Gothic altarpiece. This is what happened to Taddeo Gaddi’s mid-14th century polyptych: less than a century and a half after it was created, the polyptych was dismantled and the components of its Gothic framework, which would have included a base (predella) with painted narrative scenes, pinnacles (possibly), and piers to stabilize the entire structure (see George Bisacca, ‘The rise of the all’antica altarpiece frame’), were removed and discarded. In order to obtain the unified, rectangular picture field of the quadro required to accommodate the Gothic panels to a purpose-built, Renaissance-style frame, the pointed top of the central panel had to be cut off, the joins masked with painted classical pilasters, and the spandrels between the arched panels filled with bust-length figures of prophets. The resulting ensemble may appear to our eyes stylistically anachronistic, but the transformation at least salvaged what was clearly viewed as a venerable work of art.

This kind of updating was more common than might be thought. Two polyptychs by Giotto – one for the church of the Badia (now in the Gallerie degli Uffizi) and another for a chapel in the Florentine church of Santa Croce – were subjected to a similar ‘updating’ (in both cases, the Renaissance framing has now been removed but retained).

Fra Angelico (c.1395-1455) & Lorenzo di Credi (1459-1537), Altarpiece of Fiesole, 1420s and 1501/1520s, tempera/panel, now 212 x 237 cm., Convent of San Domenico, Fiesole

In 1501 Fra Angelico’s early polyptych in the Convent of San Domenico, Fiesole, was radically updated under the direction of Lorenzo di Credi. The motivation was the renovation of the tribune of the church, and the objective was clearly to salvage a work by the convent’s celebrated painter, whilst giving it a more modern appearance.

Giovanni di Paolo (1398-1482), Madonna & Child with saints, 1454, tempera/panel, 210.2 x 151.1 cm. overall, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Although Giovanni di Paolo’s mid-15th century altarpiece (from a church in the Tuscan town of Cortona) was spared this radical modernization, it has been deprived of its pinnacles, finials and buttresses, as well as the scenes of its historiated predella. Reconstructing the intended appearance of these dismantled altarpieces and identifying their original location is a continuing part of art historical research. In the case of Giovanni di Paolo’s polyptych, the scenes which once decorated its predella have been identified with a series of panels recounting the life of St John the Baptist now in the National Gallery, London , whilst the pinnacle panels with half-length figures are in a private collection in Italy. What still seems surprising is that The Met’s panels, which constitute a work of considerable size – plainly created for an ecclesiastical setting – found a place in the New York residence of Michael Friedsam, one of the great benefactors of The Met. But Friedsam – a close associate of Benjamin Altman, whose lead in collecting he emulated – was a rare exception, and since the paintings in The Met’s collection are largely gifts and bequests from private collectors, it is not surprising that the collection includes relatively few more or less intact Gothic altarpieces.

Master of Rousillon (attrib.; fl. 1385-1428), Retable with scenes from the life of St Andrew, c.1420-30, tempera/panel, 313.1 x 314 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The finest examples of these are 15th century Spanish altarpieces, amongst which is the Retable with scenes from the Life of St Andrew, above, with its delicate tracery of arcaded round-topped arches, and backboard with trailing vines. Other examples are the Madonna & Child enthroned with scenes from the Life of the Virgin by the Morata Master, late 15th century ; and (also late 15th century) the Castillian Madonna & Child with the Pietà and saints.

Spanish School, c.1400, The Trinity adored by all saints, tempera/panel, c.172 x 158.1 cm. overall, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The early 15th century The Trinity adored by all saints from the Monastery of Valdecristo, Altura, is another complete work, with painted angels on the backboard above its leafy gold finials.

Courtyard of Vélez Blanco in the Blumenthal house, New York (now installed in the Metropolitan Museum), with the Castillian Madonna & Child with the Pietà and saints, late 15th century

Remarkably, two of these Spanish retables belonged to the collectors George and Florence Blumenthal, and were among the many mediaeval and Renaissance works of art installed in their mansion on Park Avenue and 70th Street, which had as its defining feature the Renaissance courtyard from the abandoned Castillo de Vélez Blanco in Andalusia, where, on the balcony, one of these altarpieces – the Castillian Madonna & Child with the Pietà and saints – can be seen.

Fortunately, from a remarkably early date we hear of collectors who valued even the fragments of discarded altarpieces – works which were valued as documenting the early ‘primitive’ phase of European painting. In his life of Giotto, Giorgio Vasari reports that a member of the Florentine Gondi family, ‘a lover of these noble arts’, sought out the pieces of a work by Giotto which had been cut up, and which was painted ‘with small figures’, to add to his collection.

Giotto (1266/76-1337)), Adoration of the Magi, c.1320, tempera/panel, 45.1 x 43.8 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

This reference has sometimes been associated with The Met’s The Adoration of the Magi, which belongs to a series of seven scenes portraying the life of Christ, now divided amongst three museums and the Berenson collection at Villa I Tatti outside Florence. The seven scenes were originally painted on a single, horizontal plank of wood, each scene divided from the other only by a thin strip of gold. Today the individual panels are displayed either in simple mouldings or without any frame, but in the 16th and 17th centuries they would inevitably have been put into more elaborate contemporary frames. What the original function of this unified series may have been – a dossal positioned at the back of the altar, such as was common in the 13th century but would have been unusual in the 14th, or perhaps part of a larger ensemble? – remains a matter of speculation.

Physical evidence for the radical transformations of panels from dismantled altarpieces or ensembles is documented in four exceptionally beautiful panels by the Florentine painter and miniaturist Lorenzo Monaco, depicting Old Testament prophets and patriarchs. Unfortunately, we know nothing about the history of these panels prior to 1841, when they were already in a private collection in Florence – probably victims of the Napoleonic suppression of religious convents in 1810 and the consequent dispersal of religious artifacts.

Lorenzo Monaco (c.1370-1425), Moses, c.1408-10, tempera/panel, 62.2 x 44.5 cm. overall, Metropolitan Museum, New York

As is so often the case, the function of the series and their original configuration remain a matter of conjecture, but three of the panels preserve the traces of their re-configuration. Although the wood supports are rectangular in shape, it is clear from the gold background, which preserves its raised edge (or barbe) that originally the picture field was arched, with an engaged Gothic frame. Perhaps as early as the late 15th century the original frames were prised off, and the pictures were put into frames with a rectangular opening which significantly reduced the picture field at the sides. The nail holes around the perimeter of the panels document this reframing, as do the inscribed lines on the wood, and the wear on the vertical portions of the composition which were covered by the frames. At this point it was necessary to fill the spandrels between the gilded background and the rectangular opening with gesso and a reddish-coloured paint.

Lorenzo Monaco, Moses, in 20th century Gothic revival frame

Whether the panels were then hung individually or incorporated into a series within a single frame cannot be guessed, but at some point these frames were also removed. Only following the acquisition of all four panels by Wildenstein Galleries in 1956 were the modern, reproduction Gothic frames we see today created for them.

A similar fate befell Fra Carnevale’s Birth of the Virgin of 1467. In this case we know that the altarpiece to which the panel belonged, together with a companion in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, was dismantled in 1632. The two paintings were taken to Rome to form part of the prestigious collection of the Barberini family. What was certainly an elaborate Gothic frame, such as was favoured in the region of the Marche, was discarded and, according to Barberini inventories, the picture was put into a painted walnut frame. Since it entered The Met’s collection in 1935, the panel has been displayed in a 16th century gilded cassetta, which has nothing to do with its original appearance.

Crivelli (fl. 1457-94/95), Pietà, 1476, tempera/panel, 71.1 x 63.8 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Cardinal Antonio Barberini (1607-71) was an avid collector of old as well as of contemporary works of art, and he seems to have been responsible for removing Crivelli’s Pietà from the imposing Gothic polyptych to which it had belonged (the main panels are now in the National Gallery, London). Deprived of its Gothic frame, which was an applied one rather than engaged, in keeping with Venetian practice, the Pietà was treated as an independent picture. At some point additions were made to the elaborately tooled gold background as well as the veined marble tomb, and when the painting was acquired by the museum in 1913, it was in the very fine 17th century frame in which it is still displayed. The frame is ornamented at the corners with bees, the emblem of the Barberini (see ‘Bees in the frame: Part 1 – the Barberini bee’), and although its style may strike us as anachronistic, it eloquently conveys the interest such fragments enjoyed in the antiquarian culture of the 17th century. But it took a revolution in taste over the course of the 19th century (an event explored percipiently by Francis Haskell almost a half century ago) to transform this antiquarian interest in ‘primitives’ to an appreciation for their intrinsic qualities and – of particular interest in the present essay – the desire to frame them in what was thought to be a chronologically-appropriate way.

Recreating Renaissance splendour

In her 1940 novella, False Dawn, Edith Wharton tells the story of a young American – Lewis Raycie – who, while travelling in Europe, encounters the British critic and apologist for mediaeval art, John Ruskin. Converted by Ruskin to the nascent fashion for early Italian painting, Raycie forms a collection which he optimistically opens to an unresponsive public. Wharton’s protagonist was inspired by a real person – the New York collector, Thomas Jefferson Bryan (1800?-1870), who in 1852 opened his Gallery of Christian Art in the New York Society Library at 348 Broadway.

Lo Scheggia (Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi; 1406-86), The triumph of Fame, Medici desco da parto, c.1449, tempera, silver and gold leaf on panel, 36 ½ ins (92.7 cm.) diam. overall, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The Met’s Triumph of Fame – a ceremonial birth tray or desco da parto, painted to celebrate the birth in 1449 of Lorenzo de’ Medici, ‘il Magnifico’ (it later hung in Lorenzo’s bedroom in Palazzo Medici) – belonged to Thomas Bryan and it retains its original engaged frame. Although partly regilded, the frame still bears the tricoloured feathers used by Piero de’ Medici, Lorenzo’s father, as one of his personal devices. It’s not without interest that when Bryan acquired this talismanic object from a notable French collection in 1851, it was ascribed to Giotto. Bryan’s gallery in New York may have been regarded with indifference, but by the mid-19th century in Europe dealers were confronted with a rising fashion for early Italian painting.

J.P. Morgan’s private library. Photo: The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

To take advantage of this burgeoning market demand, which came to America a couple of generations later, they sought ways to enhance the appearance of these ‘primitive’ works so that they would fit into the opulent interiors of wealthy collectors such J.P. Morgan, whose private library (above) is conspicuously fashioned to suggest the dwelling of a Medici prince. From around 1925, the Duveen firm employed the Sienese-born framemaker Ferruccio Vannoni (1881-1965) to create frames in either Gothic or Renaissance style for the early paintings which passed through its hands. As Karen Serres has noted in a detailed study of this talented craftsman,

‘Vannoni’s extant frames can be divided into four broad categories, and a number of particular styles and techniques can be identified: extravagant Neo-gothic frames, found mainly on trecento panels and works by Carlo Crivelli; tabernacle frames, used for Florentine quattrocento religious subjects; painted cassetta frames, fitted on Renaissance portraits; and cassetta frames with pulvinated and pierced foliate friezes, for Venetian cinquecento masterpieces’ [1].

Crivelli (fl.1457- d.1494/95), Madonna & Child, c.1480, tempera/panel, 37.8 x 25.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

All these styles are present in The Met’s collection. Vannoni made the elaborate, Gothic-style frames for two paintings by Carlo Crivelli (Madonna & Child, above, and Madonna & Child enthroned), and for another by his brother Vittorio (Madonna & Child with two angels).

Filippino Lippi (c.1457-1504), Madonna & Child, c.1483-84, tempera/panel, 81.3 x 59.7 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

He also made the Renaissance-style aedicular frames on paintings of the Madonna and Child by Filippino Lippi (above), and Signorelli (below).

Luca Signorelli (fl.1470-d.1523), Madonna & Child, c.1505-07, o/panel, 51.4 x 47.6 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

His success can be measured by the fact that three of these works were acquired from Duveen in 1927-28 by the discriminating banker, philanthropist and collector Jules Bache, who bequeathed them to The Met in 1949. In what must have been a marketing ploy, Vannoni boldly, if inappositely, trumpeted Signorelli’s authorship by inscribing the artist’s name on a strip within the opening of the frame: ‘Luca Signorelli Pinxit’, or ‘Signorelli painted this’. Although Vannoni’s frames were invariably based on precise historical examples and their quality of execution fully justifies his reputation, a key factor of their success was their ostentatious brilliance, designed to look completely at home in the interiors of America’s Gilded Age. One can only imagine how Signorelli himself would have framed this painting, which was created a gift to his daughter rather than as an ornament of a princely interior.

Cosmè Tura (c.1433-95), The flight into Egypt, 1470s, tempera/panel, 39.7 x 38.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

What this new breed of American collector preferred was individual paintings by recognized masters, framed so as to seem not only rare but complete and prestigious. This meant that individual panels from disassembled altarpieces had to be presented in a way which both ignored and transformed their fragmentary state. A typical example is Cosmè Tura’s haunting The Flight into Egypt – another of the bequests of Jules Bache. It is one of three circular paintings or tondi from the predella of an important, highly complex altarpiece, now dispersed (two further predella panels are in the Harvard Art Museum and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston; each differently framed). Vannoni designed a splendid aedicular frame for The flight into Egypt, replete with finely-decorated pilasters and a handsomely ornamented entablature, so as to give it the appearance of an important free-standing work of art from the Este court of Ferrara.

Cosmè Tura (c.1433-95), Madonna of the Zodiac, 1480s, tempera/panel, 61 x 41 cm., Gallerie dell’ Accademia, Venice

Vannoni derived the individual architectural features from the frame on another painting of the Madonna and Child by Tura in the Accademia in Venice, a work conveniently reproduced in Michel Angelo Guggenheim’s 1897 source book, Le cornici italiane dalla metà del secolo XVo allo scorcio del XVIo.

Crivelli (fl.1457- d.1494/95), Altarpiece of Sant’ Emidio, 1473, tempera/panel, c. 290 x 280 cm., Cattedrale di Sant’ Emidio, Ascoli Piceno

The same modus operandi had been used for the frame Vannoni made for Crivelli’s Madonna and Child (illustrated earlier); he modelled the intricate Gothic design on the untouched polyptych by Crivelli in the cathedral of Ascoli Piceno, above.

Crivelli (fl.1457- d.1494/95), La Madonna della rondine, post 1490, tempera & oil/panel, 150.5 x 107.3 cm.; predella 29.2 x 145.5 cm., National Gallery, London

However, in this case he was almost certainly mistaken, since the rectangular picture field suggests that the original frame was probably a Renaissance design – perhaps of a type similar to the frame on the artist’s altarpiece from S. Francesco dei Zoccolanti in Matelica, now in the National Gallery. But in the 19th and 20th centuries Crivelli was invariable classified as a ‘Gothic’ artist, so Vannoni obliged with ‘Gothic’ frames.

Duccio (fl.1278-d.1318), Madonna & Child, c.1290-1300, tempera/panel, overall 27.9 x 21 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Fortunately, a number of Italian paintings in The Met’s collection which were conceived as independent works for private devotion have come down to us with their original frames intact. Duccio’s Madonna and Child should be included amongst the most significant examples; the bottom edge of the simple moulding bears traces of burns from a candle – a poignant reminder of the devotion it inspired.

Michele Giambono (fl.1420-62), Christ as the Man of Sorrows, c.1430, tempera/panel, overall 54.9 x 38.7 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Similarly, Giambono’s Man of Sorrows is still in its engaged frame, decorated with barley-sugar columns and lace-like tracery in the spandrels (typical of the refined work of Venetian craftsmen). The reverse side of the panel is painted to simulate porphyry.

Paolo di Giovanni Fei (fl.1369-d.1411), Madonna and Child, 1370s, tempera/panel, overall 87 x 59.1 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Paolo di Giovanni Fei’s Madonna and Child is another work still in its original frame (further examples are in the Lehman collection of The Met). Fei’s striking painting, combining in equal measure the frontally viewed, iconic presence of the Virgin with the touchingly naturalistic gesture of the Child reaching for his foot, preserves its exceptional frame intact. This is ornamented with glass jewels, and painted glass medallions or verre eglomisé, indicative of a prestigious commission. Such is the condition of the gilding that it is easy to discern how a compass was used to lay in the design.

Pietro di Domenico da Montepulciano (fl. first quarter 15th century), Madonna & Child with angels, 1420, tempera/ panel, overall 87.9 x 66.7 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

An engaged frame in a different style, beautifully decorated with a delicate frieze of flowers, surrounds Pietro di Domenico da Montepulciano’s panel of the Madonna with her sleeping child, seated in a Paradisical garden. The flowers are probably intended as a vine bearing roses, an attribute of the Virgin, or they may echo the flowers in the painted garden – daisies for humility.

Pietro Lorenzetti (fl.1320-44), Crucifixion, 1340s, tempera/panel, overall 41.9 x 31.8 cm., and reverse, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Pietro Lorenzetti’s beautifully preserved Crucifixion, which is the only intact panel from what must have been an important series of modestly-sized panels depicting the Passion of Christ, also retains its original frame (the reverse of the panel is painted to simulate marble and is further embellished with tooled silver). Another panel from the series is held (now cut out of its own engaged frame) in the Pinacoteca Vaticana.

Simone Martini (fl.1315-d.1344), St Andrew, c.1326, tempera/panel, overall 57.2 x 37.8 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Three panels from a five-panel portable altarpiece by Simone Martini also retain their original delicately-tooled frames. The frames were detached from the painted panels in the early 20th century (the frame of a related panel in the J. Paul Getty Museum is still engaged), but were not discarded; they were re-used for the same panels. Their simple cassetta structure and profile and the punchwork decoration provided the template for carvers and gilders for the next century or so in Siena, and were much imitated by modern framemakers, such as Vannoni. However, such relatively simple framing solutions must have seemed inadequate to some collectors, especially in the 19th century, when the vogue for anything NeoGothic – from the plots of novels to elaborate cases for clocks – was at its height.

Lippo Memmi (fl.1317-d.1356), Madonna & Child with saints & angels, c.1350, tempera/panel, overall 66.7 x 33 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Thus it is not surprising that well before 1919, when Duveen acquired Lippo Memmi’s Madonna & Child from Richard Norton, the son of the Dante scholar, Charles Eliot Norton, and director of the Archaeological Institute of America, the panel had undergone what now seems an extremely unfortunate and completely unnecessary transformation. Evidently to give The Met’s work a more decisively ‘Gothic’ appearance in conformity with Victorian taste, its original simple engaged frame was removed and the lower part of the panel was separated from the main composition, so that a projecting moulding now separates the diminutive depictions of saints beneath an arcade – ingeniously created by punching the design into the gold leaf background – from the Madonna and Child with angels. In essence, a clearly separated predella was created. A more complex frame was then applied around the painting, employing pilasters and NeoGothic crockets on the gable. The result resembles an independent miniature altarpiece which has little to do with original 14th century designs.

Lippo Memmi (fl.1317-d.1356), Crucifixion, c.1340, tempera/panel, overall 60.8 x 28.8 cm., Musée du Louvre

The original appearance of the painting can be ascertained from a companion panel in the Louvre, which fortunately retains its original very simple moulding.

Lippo Memmi (fl.1317-d.1356), St Clare, c.1330, tempera/panel, overall (in modern frame) 48.3 x 20.3 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Reconstruction of an altarpiece by Lippo Memmi (fl.1317-d.1356), for (?)San Giovanni Battista, San Gimignano, c.1325-30; the coloured panels (from left) St Paul, Metropolitan Museum, St John the Baptist, NGA; St Peter, Musée du Louvre, and St Clare (above), Metropolitan Museum

Precisely the same sort of transformation was perpetrated on the artist’s small panel of St Clare, which, as it turns out, originally formed a pinnacle to the same important altarpiece as the artist’s St Paul (above). That panel was deprived of its framing elements, but fortunately escaped a similar neo-Gothic reframing.

Early examples of independent frames

Jacopo Bellini (c.1393-1470/71), Madonna & Child, c.1440s, tempera/panel, overall 87.6 x 63.5 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The earliest example in The Met’s collection of Italian paintings of a frame made independently of the painting it was intended for is Jacopo Bellini’s – alas, much compromised – Madonna and Child of the 1440s. The practice of creating a frame independent of, rather than attached to, the pictorial support was already a possibility in 14th century Venice and its territories. This innovation made it possible to speed up the production of works of art by allowing the painting to be executed simultaneously with the construction of the frame.

Jacopo Bellini (1396-1470), drawing for a frame with a Lamentation over the Dead Christ, Paris drawing book, c.1455-60, pen-&-ink on vellum, 38 x 26 cm., Musée du Louvre

Although the frame on The Met’s picture is Gothic in style, Bellini père was keenly aware of the innovative classicizing architectural style developing in Florence, and, in a drawing in the Louvre, he depicts a beautifully articulated aedicular frame, such as would become current in Venice as well by the 1460s.

The Ricordanze or record book kept by the Florentine painter Neri di Bicci (1419–91) provides many examples of the artist commissioning a frame from a woodworker at the same time that the order was placed for the panel support on which he would paint. For example, on 19 September 1459, Neri agreed with the silk merchant Giovanni di Nofri del Chaccia to execute an altarpiece for the monastery at Cestello,

‘…in the following manner, that is all’antica, square, with columns at either side and a predella at the base and above an architrave, frieze and cornice, gilded with fine gold where appropriate…’ [2].

He then subcontracted with the celebrated woodworker, architect and sculptor Giuliano da Maiano for the panel and frame.

Benvenuto di Giovanni (1436-post 1518), Madonna & Child, c.1470, tempera/panel, 70.5 x 46 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The Madonna and Child in the Lehman Collection, by the Sienese painter Benvenuto di Giovanni, must have resulted from just such an arrangement with a professional woodworker. The painting dates from around 1470, and the panel on which it is painted has an engaged ogee moulding, finely carved with a classical leaf-&-dart, which now serves as a sort of interface for the independently constructed and striking tabernacle frame in which it is displayed.

Benvenuto di Giovanni, Madonna & Child, in its contemporary (possibly original) outer frame

Although we cannot be certain that this tabernacle frame is original to the picture or is a somewhat later addition, it is Sienese, of the finest quality; and its elaborate candlestick colonets and the antependium ornamented with a cherub’s head perfectly complement the sharply-defined and hyper-elegant forms of the painting, which read like a sculptural relief. Neri di Bicci referred to frames of this sort as ‘uno tabernacholo al’anticha’ – a tabernacle in the antique style [3]. It was frames in this style which were emulated in the early 20th century for American collectors of Renaissance paintings.

Botticelli (1444/45-1510), The last communion of St Jerome, early 1490s, tempera/panel, 34.3 x 25.4 cm., with replacement frame, probably by Giuliano da Maiano (1432-90), the lunette by Bartolomeo di Giovanni (fl.1488-d.1501), The Trinity, tempera/wood, Metropolitan Museum, New York

In 1989 the Museum replaced the pseudo-Renaissance frame, in which Botticelli’s Last Communion of St Jerome was displayed when it hung in the collection of Benjamin Altman, with a well-preserved and exquisitely carved giltwood frame – equally as rare and beautiful as the frame of the Benvenuto di Giovanni Madonna & Child – from the workshop of Giuliano da Maino.

Ferruccio Vannoni (1881-1965), Renaissance-style aedicular frame executed for Neroccio de’ Landi, Madonna & Child; now replaced

Neroccio de’ Landi (1447-1500), Madonna & Child with SS Jerome and Mary Magdalen, c.1490, tempera/panel, 61 x 43.8 cm., with replacement frame by Francesco di Giorgio, the lunette attrib. to his workshop, The Man of Sorrows with two angels, c.1470, tempera/wood, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Similarly, in 1996, a Renaissance-style frame [4] made by Vannoni for Neroccio de’ Landi’s Madonna & Child was replaced with an exceptionally fine period frame. As was the case with Botticelli’s St Jerome, not only did the frame fit Neroccio’s painting, requiring only an inlay at the base of the opening, but it was designed by the leading sculptor and architect, Francesco di Giorgio, who in 1469 established a compagnia with Neroccio. The repainted and regilded inscription for the Virgin Annunciate is balanced on the apron by a star bursting from a lily, combining two attributes of the Virgin.

Lorenzo di Credi (1456/59-1536), Madonna adoring the Child with the Infant St John the Baptist & an angel, early 1490s, tempera/panel, diam. 91.4 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

The common setting for paintings of the Madonna and Child in smallish aedicular and tabernacle frames was the bedroom of a private residence, where evening prayers would be said. By the late 15th century a further choice might be a circular painting – a tondo da camera. The most distinguished example of this type of picture in The Met’s collection is Lorenzo di Credi’s Madonna adoring the Child, displayed in frame made in Florence in 2014 which faithfully replicates an original frame on a 15th century version of The Met’s picture in the Uffizi . Small tondi to hang above the bed were equally popular in the Netherlands: Hans Memling’s Virgin and Child is an example, dating from around 1480-85.

Biagio d’Antonio (fl.1472-d.1516), Scenes from the story of the Argonauts, tempera/panel, overall 61.3 x 153.4 cm.; Jacopo del Sellaio (1441/42-93), Scenes from the story of the Argonauts, tempera/panel, overall 61.3 x 152.7 cm.; Metropolitan Museum, New York

The pair of panels painted by Biagio di Antonio (upper image) and Jacopo del Sellaio (lower image), narrating episodes from the story of Jason and the Argonauts, could also have found their place in a bedroom. The Met’s panels must date from sometime between 1469 and 1472, when the two artists involved established an association or compagnia, and undertook commissions for cassoni or wedding chests and domestic furnishings such as The Met’s two panels, which might have been placed above a day bed or in the wainscot of the room.

Like Benvenuto di Giovanni’s Madonna & Child, the two panels have a narrow engaged frame with a fillet at the top edge and an ogee to the sight; they offer a particularly fascinating example of the ways in which this sort of moulding might be personalized. Rather than with the more common leaf-&-dart, the ogee at the sight edge is carved with oak leaves and acorns. These are well-known emblems of the Della Rovere family, and although the possibility that the pictures might in some way be related to this powerful papal family has yet to be explored [5], the choice was unlikely to be casual. It is possible that the oak leaves are intended to recall the sacred oak tree of Zeus at Dodona, since the Argo was said to have a branch of that tree, given by Zeus to Jason, mounted on the prow like a figurehead, where it could speak and prophesy.

Bugiardini (1475-1554), Madonna & Child enthroned with SS Mary Magdalen & John the Baptist, c.1523, o/panel, 193.7 x 165.7 cm., and details of decoration, Metropolitan Museum, New York

By the time the works discussed in this section were painted, independent frames had become the norm for both smaller works and for altarpieces. The finest example of an all’antica altarpiece frame in The Met’s collection is that of Bugiardini’s Madonna & Child enthroned with saints. The design of the frame, which is original to the picture, has been ascribed to the prominent Florentine woodcarver, sculptor, and architect Baccio d’Agnolo (1462-1543), and the finely painted grotesque decoration on the pilasters to a specialist in the genre, Andrea di Cosimo Feltrini (1477-1548). Functioning less as a fictive window than as a proscenium behind which the scene is staged, the frame beautifully complements the geometry of the architectural setting where the sacred figures are placed. Just as the Gothic frame had provided Giovanni Fei with a space to record the name of the patron, so here the coat of arms of the prominent Altoviti family, for whom the altarpiece was painted, appear on the base.

The frame was constructed in four units which allowed for relatively easy, on-site assembly, and the system was so well devised that it is still possible to disassemble the altarpiece when it has to be moved. Of course, the ease with which a painting and its frame could be disassembled inevitably encouraged both to be viewed as independent works of art, with the consequence that few such frames were retained when the painting in question was sold and entered into an important collection (on this, see the discussion of Raphael’s altarpiece in the first essay of this series). This is particularly unfortunate, since such frames were integral to the aesthetics of the picture, and could be essential to the pictorial space imagined by the painter.

Andrea Solario (c.1465-1524), Christ Blessing, c.1524, o/panel, 203.8 x 130.8 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Take, for example, Andrea Solario’s large panel showing Christ standing before a ceremonial curtain in a carefully defined architectural space, his gaze and gesture of blessing directed towards the viewer. Christ was clearly intended to be perceived by the viewer as physically proximate, just beyond the opening of the frame. Although the original frame does not survive, there is little question that it employed the same architectural features as are depicted in the painting, so that it created a virtual extension of the pictorial space into that of the viewer, and thereby further enhanced the idea of Christ’s visionary presence (note that Solario depicts the inner edge of the lost frame illusionistically, so as to unite visually the frame and the painting). We do not know the original location of the altarpiece or whether the frame was executed in wood or carved in marble. However, as Deborah Howard has discussed in an essay on the frames of Giovanni Bellini’s altarpieces, the design depended on a close collaboration between painter and framemaker, aimed at achieving a compelling visual effect which would enhance the meditational and devotional function of the altarpiece [6].

Framing Venetian mythologies

The gallery of 16th century Venetian paintings at The Met

A more open approach applied to the frames for mythological paintings, whether commissioned by private collectors or created on spec. For 16th century Venetian work in particular, many collectors wanted richly carved frames rivalling the luxuriously patterned silks and velvets which so impressed visitors to the city. The Met’s collection of these paintings provides numerous examples.

Titian (c.1485/90?-1576), Venus and Adonis, 1550s, o/c, 106.7 x 133.4 cm., and corner detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Titian (c.1485/90?-1576), Filippo Archinto, Archbishop of Milan, mid-1550s, o/c, 118.1 x 94 cm., and corner detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The magnificent frames on Titian’s Venus and Adonis (a Venetian Baroque moulding frame dating from c.1640), and his Portrait of Archbishop Filippo Archinto (a pierced torus frame of c.1610, apparently created from ceiling mouldings) exemplify the brilliance of Venetian craftsmanship.

Veronese (1528-88), Mars and Venus united by Love, 1570s, o/c, 205.7 x 161 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Another example frames Veronese’s Mars and Venus (also Venetian, dating from c.1530-40 or later; the frieze carved with an ornamental floral chain). Not surprisingly, such frames were much in vogue among 19th and 20th century collectors and Vannoni became adept at simulating them.

Titian (c.1485/90-1576),Venus and the lute player, c.1565-70, o/c, 165.1 x 209.6 cm., and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The intricately carved frames on Veronese’s Portrait of Alessandro Vittoria and on Titian’s Venus and the luteplayer were both made by Vannoni, and, by evoking their original patrician Venetian context, flattered their modern owners. And yet we happen to know that, in the 17th century, when it belonged to the principe Pio di Savoia, Titian’s Venus and the luteplayer was displayed in an imposing white frame – a ‘cornice bianca in forma grande’. Surprising as that may sound, it should be remembered that when inventoried in 1498 in the Medici Villa at Cafaggiolo, Botticelli’s Primavera was also framed in a ‘cornicione bianco’ – most likely a cassetta – and fixed above a daybed. It would be fascinating to know whether this type of frame was associated with the function or placement of the painting and, in the case of Titian’s work, to know when the white frame was put on it. In any case, by 1724 the white frame had been replaced by a gold one. It was purchased sometime after 1742 by Sir Thomas Coke, later Earl of Leicester, and hung in Holkham Hall, Norfolk. Whatever frame it had there was once again changed by Duveen.

*************************************

This is the third of four essays forming a series under the title: ‘Framing the European paintings at The Met’. The first provides an introduction and explores the 16th -17thcentury collection, and can be found here. The second looks at the 18th and 19th century paintings: here. The fourth will address Northern paintings from the 14th -16th century.

A specialist in Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, Keith Christiansen was curator and, from 2009 to 2021, chairman of the Department of European Paintings at The Metropolitan Museum.

*******************************************

Bibliography:

In addition to the many indispensable essays by various authors on The Frame Blog, the following books and essays have been particularly important sources for these essays. I would especially like to thank Timothy Newbery for sharing his incomparable knowledge of the frames in The Met’s collection.

Reinier Baarsen, ‘Herman Doomer, ebony worker in Amsterdam’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 138, no 1124, 1996, pp. 739-49

George Bisacca, ‘The rise of the all’antica altarpiece frame’, on The Frame Blog

Isabelle Cahn, ‘Degas’s Frames’, The Burlington Magazine , vol. 131, no 1033, 1989, pp. 289-93

Alessandro Cecchi, ‘The tondo frame in Renaissance Florence: a round-up’, on The Frame Blog

Fédéric Destremau, ‘Pierre Cluzel, (1850-1894) encadreur de Redon, Pissarro, Dégas, Lautrec, Anquetin, Gauguin ‘, Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art français, 1995, pp. 239-47

Elizabeth Easton and Jared Bark, ‘ ‘Pictures Properly Framed’: Degas and Innovation in Impressionist Frames’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 150, no 1266, 2008, pp. 603-11

‘Frames in paintings: Part 1 – Gothic, Renaissance and Mannerist’, The Frame Blog, February 2023,

Creighton Gilbert, ‘Peintres et menuisiers au début de la Renaissance en Italie’, Revue de l’art, 37, 1977, pp. 9-28, republished in English as ‘Painters & woodcarvers in early Renaissance Italy’, on The Frame Blog

Helen Gramotnev, ‘Degas’s frames for dancers and bathers’, on The Frame Blog

Francis Haskell, Rediscoveries in art : some aspects of taste, fashion, and collecting in England and France, Cornell University Press, 1976

Deborah Howard, ‘Bellini and Architecture’, in Peter Humfrey, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Giovanni Bellini, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 143-66

Peter Mallo, ‘Artists’ frames in pâte coulante: history, design, and method’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, 56, 2021, pp. 160-73

Claude Mignot, ‘Le cabinet de Jean-Baptiste de Bretagne: un ‘curieux’ parisien oublié (1650)’, Archives de l’art français, n.s. 27, 1984, pp. 71-87

Paul Mitchell & Lynn Roberts, A history of European picture frames, London, P. Mitchell in association with Merrell Holberton, 1996

Timothy Newbery, George Bisacca, Laurence B. Kanter, Italian Renaissance frames, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990

Timothy Newbery, Frames, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in association with Princeton University Press, 2007

Nicholas Penny, ‘Reynolds and picture frames’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 128, no 1004, November 1986, pp. 810-25

Nicholas Penny, ‘Notes on frames in the exhibition, Portraits by Ingres’, exhibition review, February 1999, accessible on the National Portrait Gallery website:

Nicholas Penny and Karen Serres, ‘Duveen and the decorators’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 149, 2007, pp. 400–06.

Nicholas Penny and Karen Serres, ‘Duveen’s French frames for British pictures’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 151, 2009, pp. 388–94

Gemma Plumpton, ‘Framing the Renaissance’, on the Harewood website:

Bruno Pons, ‘Les cadres francais du XVIII siècle et leurs ornaments’, Revue de l’Art, no 76, 1987, pp. 41-50, republished in English as ‘18th century French frames and their ornamentation’ on The Frame Blog

Karen Serres, ‘Duveen’s Italian framemaker, Ferruccio Vannoni’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 159, May 2017, pp. 366–74; reviewed as ‘19th & 20th century Italian framemakers…’, on The Frame Blog. Further information on Duveen’s reframing can be found in the Duveen Files, available through the Getty website

Antoine Schnapper, ‘Bordures, toiles et couleurs: une révolution dans le marché de la peinture vers 1675’, Bulletin de la Societé de l’histoire de l’art français, 2000, 2001, pp. 85-104

John Shearman, ‘The collections of the younger branch of the Medici’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 117, no 862, 1975, pp. 12-27

Pieter J.J. van Thiel and C. J. de Bruyn Kops, Framing in the Golden Age: picture and frame in 17th century Holland, translated by Andrew McCormick, Rijksmuseum, 1995

The entry on John Smith from the website of the National Portrait Gallery

*******************************************

Footnotes

[1] Karen Serres, ‘Duveen’s Italian framemaker, Ferruccio Vannoni’, The Burlington Magazine, May 2017, pp. 366-74

[2] Neri di Bicci, Le ricordanze, Bruno Santi, ed., Pisa, 1976, p.121

[3] Ibid., p. 118

[4] Compare with the stylistically close frame made for Raphael’s ‘The Niccolini-Cowper Madonna’, 1508, in the NGA, Washington; Vannoni’s hand is unmistakeable, although the frames are differently ornamented and decorated

[5] When, in 1474, Giovanni della Rovere, the nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, married Giovanna di Montefeltro, daughter to Federico da Montefeltro, the compagnia between the two artists had been dissolved, so the two panels are unlikely to relate to that event

[6] Deborah Howard, ‘Bellini and Architecture’, in Peter Humfrey, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Giovanni Bellini, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 143-66