Reframing at the National Gallery, London: Part 5

This is the fifth of a series of short articles on the reframing projects undertaken by the National Gallery, London, under the Head of Framing, Peter Schade. The articles were originally published in the National Gallery’s Review of the Year, from 2008-09 onwards, and are republished here by kind permission of the Gallery, and with added illustrations.

5: Review of the year April 2012 – March 2013: Framing, by Peter Schade

Over the last eight years the National Gallery has been proactive in seeking out antique frames which are contemporary with a specific painting, but it has proved very difficult to obtain appropriate contemporary frames for our larger pictures, as fewer examples of them are available.

NG 6487 Luca Giordano (1634-1705), Perseus turning Phineas & his followers to stone, early 1680s, o/c, 285 x 366 cm., in previous 1980s Italian-made reproduction Roman ‘Salvator Rosa’-style frame, finished with silverleaf and lacquered

However, this year we were able to replace the silvered moulding frame surrounding Perseus turning Phineas and his followers to stone (NG 6487) by Luca Giordano (1634-1705) with an original carved and partly-gilded 17th century Florentine frame. In common with many frames which were made or modified for National Gallery paintings in the 1970s-80s, the silvered frame was a fusion of historic style – a modern version of an 18th century-style Roman ‘Salvator Rosa’ moulding – and an invented colour scheme intended to harmonize with elements in the composition: in this case the silvery grey warriors being turned to stone. The frame had the effect of flattening the composition, and failed to do justice to this colourful and dynamic scene.

NG 6487 Luca Giordano (1634-1705), Perseus turning Phineas & his followers to stone, early 1680s, o/c, 285 x 366 cm., reframed in a mid-17th century Baroque Florentine reverse frame, carved, with spiral ribbon at back edge; flat frieze with scrolling acanthus leaf corners holding mascarons and scrolling foliate-&-shell centres; stylized leaf-&-tongue; stopped-channel fluting curled over an undercut bird’s beak moulding at the sight edge; painted in pale ochre/terra cotta and picked out in parcel-gilding

The newly-acquired Florentine frame changes our perception of the painting dramatically, and underlines its status as a highlight of the collection. Its apparently effortless light finish is the result of a very sophisticated scheme of gilded and burnished highlights on a background painted with yellow ochre, achieving the impression of a fully gilded frame, whilst using only a quarter of the gold leaf which that would need. The tonality of the frame helps to set the colours in the painting in their intended relationship to one another, and brings them to life. The prominent central cartouches emphasize the diamond-shaped composition of the figures and intensify the perception of space.

Giordano, detail of frame with corner mascaron

This is arguably the most significant frame acquired by the National Gallery in the last sixty years. It is a striking and typical example of mid-17th century Florentine palace design, similar to frames found in the Pitti Palace. The carved cartouches, particularly the expressive masks in the corners, are artistic in concept and execution – designed so that they simply look like Auricular or fleshy scrolling ornament, but turn into masks when examined more carefully. Luca Giordano, who worked in Florence as well as other cities in Italy, would have been familiar with ornament of this kind, and indeed some of the metal vessels tumbled in the foreground of the painting are not dissimilar in character. Here, 17th century Auricular ornament, popular in Venice but also in Northern Europe, is subjected to the Florentine desire for symmetry and classical values.

Frames of this quality are rare and cannot be obtained without expense. This example alone, bought in 2011, would have exceeded the Framing Department’s annual acquisition budget, and we are indebted to the generosity of a group of private donors who have made its purchase possible.

Note: The frame had previously been stored as four separate rails in the Palazzo Serristori in Florence, having been in private hands before this. It was cut transversely on the short side, as evident on the left of the corner image (above), in order to facilitate its rescue in the 1968 floods in Florence; otherwise, it was unrestored and of its original size.

**********

Paintings reframed in 2012-13

Framed with newly acquired antique frames

Fra Bartolommeo

NG 3914 Fra Bartolommeo (1472?-1517), The Madonna adoring the Christ Child with St Joseph, pre-1511, o/panel, 137 x 104.8 cm., in previous late 17th century Baroque Italian (Roman?) panel frame with ogee and stepped profile; engraved with shaped panels of foliated strapwork on a cross-hatched ground at corners and centres, with burnished reposes; applied to the painting between 1962-64

NG 3914 Fra Bartolommeo, The Madonna adoring the Christ Child with St Joseph, reframed in a 16th century Italian cassetta, having an entablature profile with a plain frieze, the latter with horizontal butt joints on the façade; finished with the original untouched water-gilding and patination

The simplicity and spareness of this cassetta (contemporary with the painting) echoes the emphasis given in the composition to the poverty of the Holy Family, fugitives in their homeland. The ruined classical building behind them symbolizes the pagan Roman empire which is already passing away and will be superseded by Christian civilization; in the Renaissance, the classical was remade in Christian form, rendering this classicizing frame as symbolically appropriate for the subject as it is optically generous – opening the composition to the viewer’s contemplation without any decorative intervention.

NG 3914 Fra Bartolommeo, details of the ‘new’ 16th century frame: above, as it was acquired, and below, on the painting

Claude, Le Lorrain

NG 1319 Claude (1604/5?-82), A view in Rome, 1632, o/c, 60.3 x 84 cm., in previous late Victorian British or Continental reproduction Louis XIV carved giltwood ogee frame, with projecting C-scroll foliate-&-fanned lambrequin corners and foliate-&-leaf bud centres, joined by Bérainesque-style strapwork on a faux-hatched ground; small strapwork sight edge; gilt with bronze paint

The painting may have been acquired in this frame when purchased in 1890. It is a 19th century version of the collector’s frame which, two hundred years earlier, might have displayed a landscape by Claude in a French Louis XIV interior – acclimatizing it to a decorative aesthetic some way from the painter’s own Horatian vision of his adopted city. The Victorian reproduction of this restless ornament has little of Horace’s restraint, and covers a greater area than the painting. It also contrives to flatten the internal space of the landscape, reducing it to a picturesque veduta.

NG 1319 Claude, A view in Rome, reframed in a late 17th century Baroque Roman ‘Salvator Rosa’ gallery frame, with a deep scotia profile and convex top edge; water-gilded and patinated

The antique Salvator Rosa which has replaced the 19th century frame is in every way its opposite – almost contemporary with the painting, free of ornament, a Baroque interpretation of a classical cornice. It has a much more slender rail than the previous frame, but also a robust profile of hollow and convex mouldings, generating linear shadows which emphasize the perspectival recession now leading into the landscape and drawing in the spectator. All these points explain why this became the gallery frame of the great Baroque Italian palaces; it is designed as a livery pattern to show off numbers of landscapes hung together, whilst giving each one individual depth and emphasis.

Lorenzo Costa

NG 2486 Lorenzo Costa (c.1459/60-1535), A concert, c.1485-95, o/panel, 95.3 x 75.6 cm., in previous Baroque-style bolection leaf frame, possibly 17th century, possibly later; with centred alternating leaf buds at the back edge, plain frieze and a centred spiralling acanthus-leaf torus at the top/sight edge; regilding with oil gilding

NG 2486 Costa, A concert, reframed in a 16th century reverse cassetta, with a reverse architrave profile, a centred imbricated bay-leaf at the back edge; the frieze decorated in punchwork with undulating foliage and acanthus leaf corners; a centred spiral ribbon at the top/sight edge; water-gilded on a warm bole

This quietly decorative cassetta literally illuminates Costa’s group of musicians, pushing it very slightly forward of the wall, and seeming to increase the depth of space across the internal balustrade. The large, dynamic ornament of the previous frame overwhelmed and diminished the composition; the current frame presents the painting to the viewer as though he or she is watching a living concert through a window-like opening, in which colour, tone and decoration are all in harmony, forming one complete work of art.

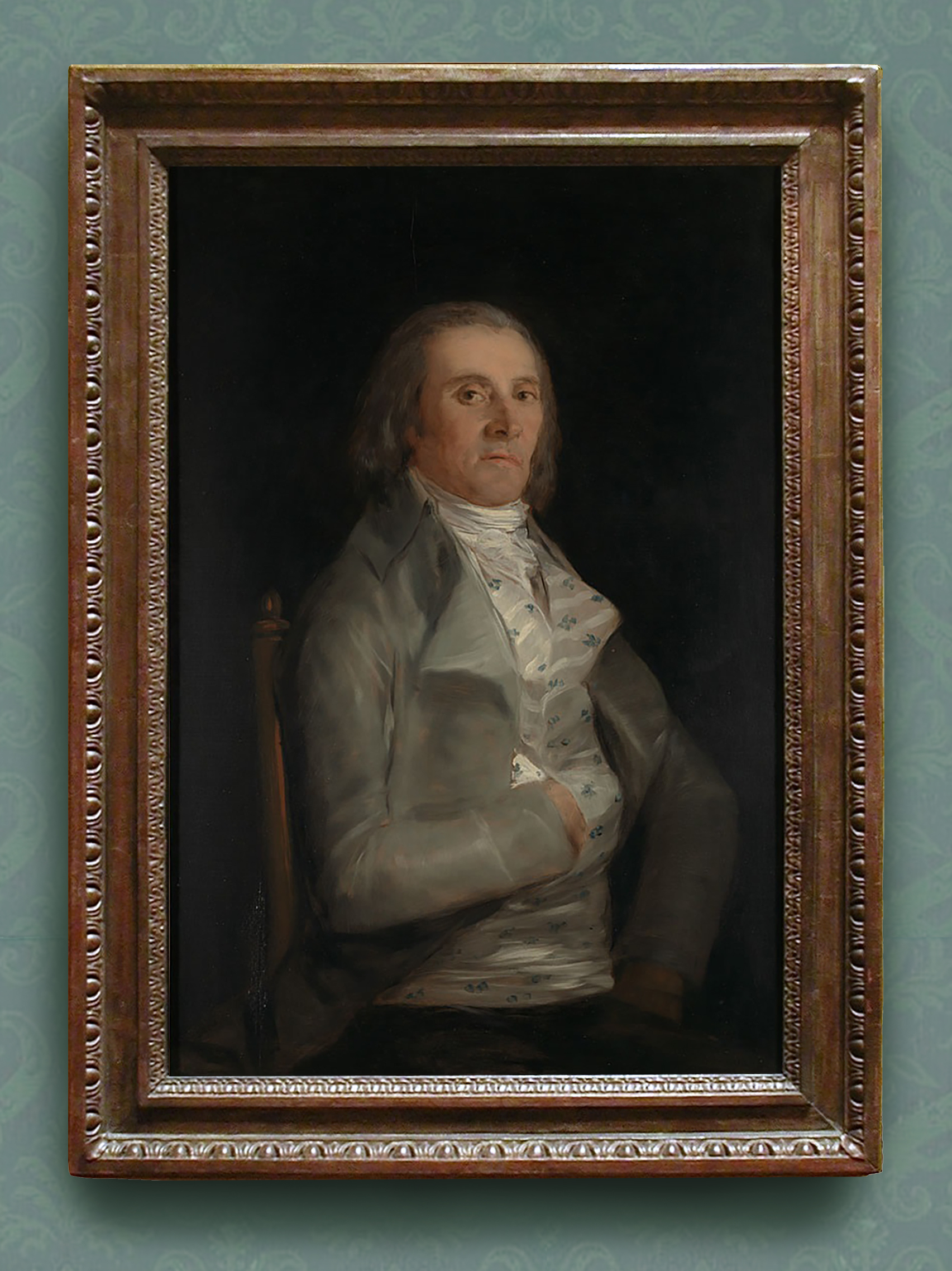

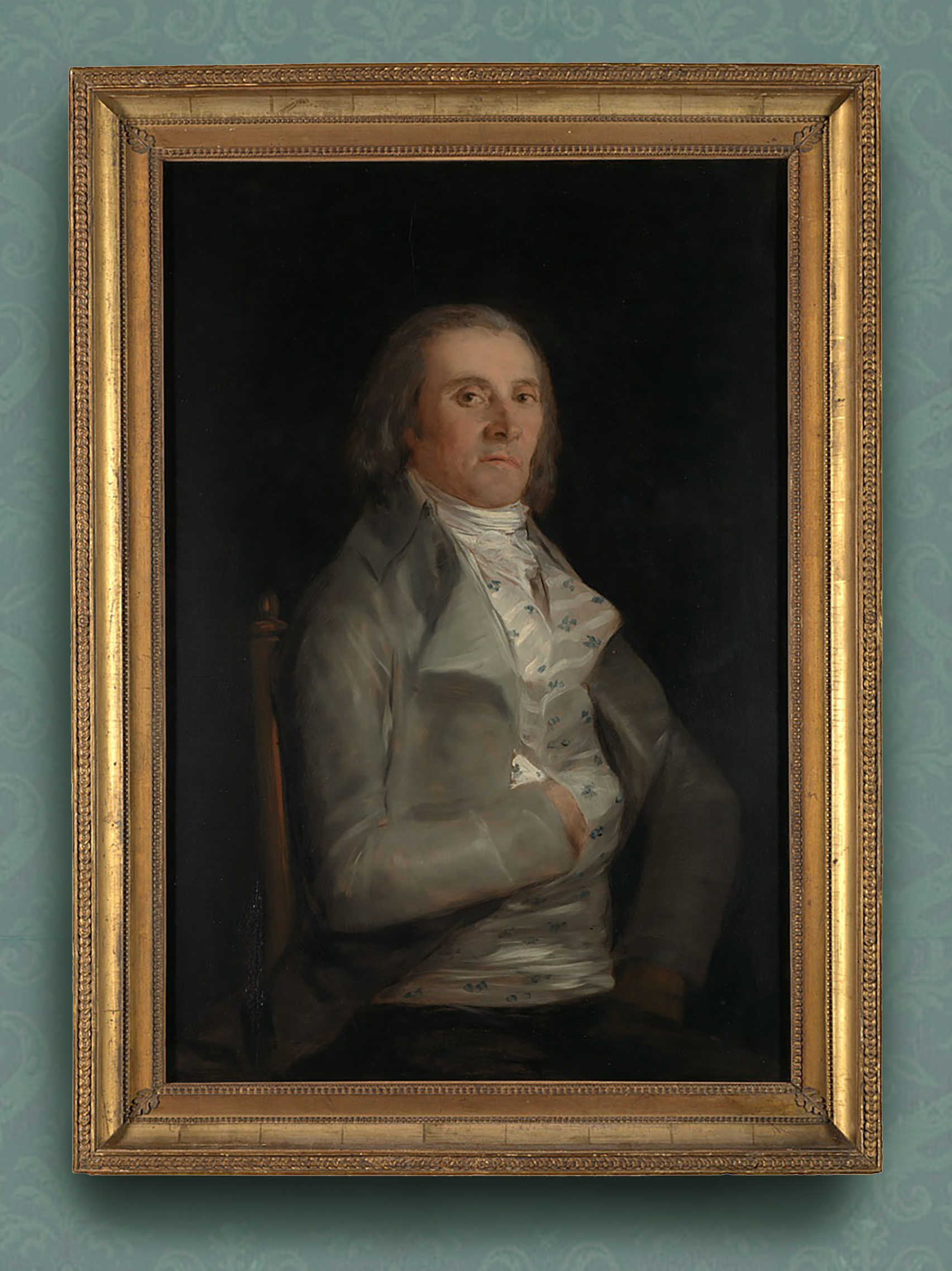

Francisco de Goya

NG 1951 Goya (1746-1828), Don Andrés del Peral, pre-1798, o/panel, 95 x 65.7 cm., in previous British (?or Continental; recorded as ‘Spanish’) NeoClassical-style entablature frame, with egg-&-dart beneath the top edge; tongue-&-dart at sight edge; purchased in 1960s Paris as gilded overall; re-gesso’d, recut, silvered over red bole and patinated

NG 1951 Goya, Don Andrés del Peral, reframed in an 18th century French Louis XVI NeoClassical frame, probably made by the Infroit workshop although lacking their stamp; concave profile with flat frieze; with centred piastre ornament on top edge; dentils; applied oak leaf at corners; leaf-&-dart at sight edge; water-gilded; and details

Don Andrés del Peral was the Spanish court gilder for nearly fifty years from the late 1770s; Goya was appointed court painter in 1786, and in 1798 both of them worked together on the royal chapel in Madrid, respectively gilding the altarpieces and painting frescos. They were also friends, and this portrait seems likely to have been given to Peral by the artist, since a century or so later it was acquired for another collection from the Peral family. With such a context, it seems almost perverse to have presented the painting in an ungilded frame, and the worn, brown appearance of the finish was hardly a happy combination with the sitter’s pearl-grey coat.

The frame chosen to replace it is related to Spanish NeoClassical profiles; it has a tiered hollow and flat frieze, outlined with very delicate ornament, and a warmth and depth to the gilding which enhances the skin tones and picks up the golden underpainting of the costume. The Infroits, father and son, were members of the large group of master framemakers in Paris who, from the mid-18th century, were obliged by the guilds of carpenters and ébénistes to stamp their products with their names; Peral has thus been given a frame by his equals as craftsmen.

Frans Hals

NG 2529 Hals (1582/83-1666), Portrait of a woman with a fan, c.1640, o/c, 79.8 x 59 cm., in previous 1960s reproduction Louis XIV-style frame, made for the Gallery by the firm of Heijdenrijk in the Netherlands; carved giltwood; convex profile with small frieze; dentil back edge; fanned lambrequins on trellised grounds in foliated cartouches at corners and centres, joined by diapered panels in foliated C-scrolls with floral sprigs; acanthus leaf-tip ogee at the sight edge; gilded and patinated

NG 2529 Hals, Portrait of a woman with a fan, reframed in a 17th century Dutch cabinetmaker’s frame (of palisander or S. American rosewood); concave profile with canted top edge; medium wide ripple moulding at the sight edge; polished and patinated

Like ebony, palisander or rosewood was greatly sought-after; it began to arrive in Europe from Macau in the 16th century, and in the 17th century from Brazil. It had a deep, rich and reddish colouring; it was strong, resistant to rot and not prone to warping; and some of its varieties were delicately scented. These qualities made it a desirable alternative to ebony; the reddish graining visible here offsets the intensely black dress and reflects the warm tones of skin, hair and ground, whilst any lingering scent of the wood must have struck a welcome note in the struggle against Baroque dirt.

The grace of the stepped and curved profile, and the restrained tones of the wood with its satiny polish, allow the rich contrasts of the costume to emerge, where before they were overwhelmed by the collector’s-style gilded frame.

Andrea Mantegna

NG 5641 Mantegna (c.1431-1506), The Holy Family with John the Baptist, c.1500, tempera/canvas, 71.1 x 50.8 cm., in previous late 16th-early 17th century cassetta with entablature profile; leaf/flowered back edge; convex fluted top edge; frieze with (possibly later) punched foliate corners; beading at sight edge with (possibly) new fillet

NG 5641 Mantegna, The Holy Family with John the Baptist, reframed in a late 16th-early 17th century Italian moulding frame, with convex profile; large-scale centred gadrooned top edge; corner-&-centre acanthus leaves; astragal-&-triple bead; water-gilded and patinated

Although the previous frame was of approximately the same period and location as its replacement, it had a very negative effect on the painting – crowding it, pushing it back, and undermining its powerful evocation of volume. The antique frame purchased in its stead is particularly suited to the sculptural cast of Mantegna’s work, and is a giltwood version of the architectural stone borders of classical Roman sarcophagi and other scenes carved in relief. The very slender rails with their inward-pointing gadroons also exercise a powerful effect on the viewer’s attention, concentrating it on the pale, statue-like figure of the Christ Child, standing centrally and right on the foreground edge on His plinth as though about to step out into the space of the Gallery.

NG 5641 Mantegna, corner detail of current frame

The Le Nain Brothers

NG 3879 Antoine (c.1600-48), Louis (c.1603-48) & Mathieu (c.1607-77) Le Nain, Four figures at a table, c.1643, o/c, 44.8 x 55 cm., in previous 18th century British ogee frame, altered (probably in 19th century) to a bolection profile above an inner cavetto; acanthus leaf at back edge; ogee with strapwork and floral sprigs on a cross-hatched ground with acanthus leaf corners; out-of-scale acanthus-&-tongue at sight edge, taken from an earlier frame

NG 3879 Le Nain brothers, Four figures at a table, reframed in a 17th century Louis XIII acanthus leaf frame; ogee profile with flowered back edge on a hazzled ground; interrupted cross-cut acanthus leaf and acanthus bud-&-floret on cross-hatched ground with acanthus leaf corners; acanthus leaf-&-dart sight edge on a hazzled ground; water-gilded

This painting sat very uneasily in its previous frame, which was not only of the wrong nationality and period but had additionally been patched together from two cannibalized frames, the cuts across the rails being very evident. The richly textured and gilded acanthus border of the Louis XIII frame, contemporary with the painting, now seems to enhance the strange dignity of the scene, endowing it with an almost religious significance. The width of the carved rail and the gently repeating S-curves of the ogee and cavetto profile cradle the image, and the depth of the gilding gives an added luminescence to the painted highlights.

Camille Pissarro

NG 4671 Pissarro (1830-1903), The Louvre under snow, 1902, o/c, 66.3 x 81.3 cm., in previous 20th century British reproduction Louis XIII-style bunched leaf torus frame in moulded plaster; with oak leaves and acorns at top edge; spiral ribbonand stylized leaf at sight edge; darkened or painted finish

NG 4671 Pissarro, The Louvre under snow, reframed in a 17th century Louis XIII acanthus-&-flower frame, with convex profile; the top edge with paired undulating acanthus leaves, alternating floret sprigs and violet flowers on a cross-hatched ground, with acanthus leaf corners; flowers on an undulating ribbon ogee at sight edge; water-gilded and patinated

The painting was acquired by purchase in 1932 from Pissarro’s son, Lucien, having been painted a year or less before the artist’s death. It is likely that it had been left unframed, and was most probably bought in that condition and framed by the Gallery, although this has not been recorded. The previous frame was a particularly heavy and ugly version of a Louis XIII-style pattern, which reduced the picture to a bleak, faded and dirty whole. It has been rescued by an original Louis XIII frame with softly gleaming aged gilding; this picks up the ochre lights in the opalescent river and sky, just as the undulating lines of the ornament echo the lines of bridge and branches. Pissarro was reconciled to gilded frames in his late fifties; having campaigned for white or partly white frames from 1877 to 1888, he wrote to Lucien in 1889,

‘The Femmes aux seaux, placed in a fine new gilded frame, did admirably, with a heightening of the tone, a comforting warmth; very powerful and rich…’ [1]

NG 4671 Pissarro, corner detail of current frame

Peter Paul Rubens

NG 680 Rubens (1577-1640), The miraculous draught of fishes, 1618-19, black chalk, ink, oil/paper on canvas, 55 x 85 cm., in previous late 17th century provincial French Louis XIII-XIV acanthus frame; centred running husks and hazzling on the back edge; convex cross-cut acanthus top edge on hazzled ground; acanthus leaf ogee with hazzled ground at sight edge; altered in the past, with the back edge off-centre on all sides

NG 680 Rubens, The miraculous draught of fishes, reframed in a 17th century Netherlandish cabinetmaker’s pearwood frame; concave profile with stepped and canted mouldings; stained and polished; rare carved giltwood sight edge with small strapwork cartouches, elongated florets and pendant husks, with acanthus leaf corners, thinly gesso’d and not recut; and detail

This dynamic composition (preparatory for an engraving), taken from and elaborated on the central panel of an altarpiece Rubens had already executed, was badly undermined by the French giltwood frame it had been given – probably after it entered the Gallery in 1861. The restless leafy mouldings, principally perpendicular to the axes of the painting, conflicted with rather than reflected the diagonal movements of torn clouds, waves and figures, and the warm, dark gilding blended too much into the brownish ochre of the ground.

The frame found in replacement was a rare and fortuitous purchase, its linear mouldings providing a wide margin of repose between wall and image which enhances the tumult of the storm and the men’s actions; the satin-like polished depth of colour in the wood simultaneously provides a foil for the areas of light around and in the figure of Christ. The exceptionally delicately carved ornament at the sight edge gives a precious accent – like a goldsmith’s chain – but the gilding is muted and soft. In a happy accident the gilt ornament is centred with sunflowers – symbolic of Christ.

Bernardo Strozzi

NG 6321 Strozzi (1581-1644), A personification of Fame, c.1635-36, o/c, 106.7 x 151.7 cm., in its previous 18th century Baroque Italian giltwood frame, with torus at top edge above a scotia; decorated with scrolling foliate and rocaille corners, palms, florets and winged shields; strapwork and cartouche centres; spiralling ribbon sight edge

NG 6321 Strozzi, A personification of Fame, reframed in a 17th century Italian (Sicilian) Mannerist panel frame in pinewood, with a canted reverse or bolection profile; continuous long fluted leaves on back edge; strigillated frieze interrupted by cross-cut acanthus leaves; acanthus leaf corners; small strigillated moulding at sight edge, with corner leaves; gilded and patinated

Strigillated ornament, which borrows its name from the ‘S’-shaped massaging tools used in the baths of classical Greece and Rome to scrape the skin clean, was a variation on parallel flutes – a literal twist, which gave them a wave-like form. In this guise they are frequently found decorating panels of antique sarcophagi, where they add dynamism and movement to static relief sculptures. In 16th and 17th century Italy, classical remains still studded urban streets and filled private collections, providing ornamental inspiration for architects, artists and sculptors. Twisted, S-shaped flutes were particularly attractive to the Mannerist distortion of classical proportions and ornaments, and soon migrated to the decoration of frames.

There was no analogous classical pedigree for the study of sound, which only seems to have been seriously considered as a science from the 17th century, but if the patron who commissioned this painting from Strozzi had known that the year it was executed was the same year that Marin Mersenne’s Harmonie universelle (containing the mathematical formula for the vibration of a plucked string) was published in Paris, he might have regarded quite enviously its reframing by the National Gallery in a moulding decorated with what could be seen as the vibrations of Fame’s trumpet carved in gold.

South German School

NG 722 15th century South German School, Portrait of a woman of the Hofer family, c.1470, o/panel, 53.7 x 40.8 cm., in previous 19th century British revival Northern Gothic rainsill frame; deep scotia on three sides and wide canted sill at base; inner frame of stepped astragals with inlay at sight edge; ebonized and polished, with parcel-gilt contours

The previous frame may have been made for the Gallery by Henry Critchfield shortly after the painting was presented by Queen Victoria in 1863. The glossy black and gilt Elizabethan-revival frame made for the portrait of Bess of Hardwick in the National Portrait Gallery after 1865, also by Critchfield, is very much in the same revivalist taste.

NG 722 15th century South German School, Portrait of a woman of the Hofer family, reframed in 16th century cabinetmaker’s frame in walnut, with deep torus moulding at the top edge and flat frieze; pearls at the sight edge; stained, polished, and parcel-gilt at sight

Such a delicate and graceful painting as this South German portrait was singularly ill-served, however, by its chunky, shiny 19th century frame. The warm, glowing wood of its replacement harmonizes with the sitter’s skin tones, and the row of pearls at the sight edge echo her studded brown collar, the pins in her headdress, and even the tiny round petals of the forget-me-not flowers she holds. Although her fingers only appear to rest on the inner edge of the bottom rail in the trompe l’oeil custom adopted by 14th-16th century portraitists, the fact that the new frame brings her forward – almost into the spectator’s space – helps and is helped by the painted illusion, which was all but unnoticeable in the previous frame.

Cosimo Tura

NG 3070 Tura (pre-1431-95), A muse (Calliope?), c.1455-60, oil & tempera/panel, 116.2 x 71.1 cm., in previous 16th century Italian (?Venetian) frame with bolection profile; flowered ogee back edge; carved and extravagantly pierced scrolling foliate-&-flower bud torus moulding applied over an (unusually) flat gilded frieze; flowered sight edge; probably altered in 19th century; may have been on the painting when in the collection of Austen Layard, by whom bequeathed in 1916

NG 3070 Tura, A muse (Calliope?), reframed in a mid-15th century Italian architectural moulding frame; stepped profile with a deep ogee; water-gilded and patinated

The Gallery’s Muse was once one of a set of nine decorative panels commissioned by a duke of Ferrara for his studiolo, which was otherwise decorated with inlaid wood (perhaps similarly to the studiolo from Gubbio, now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York). It would probably therefore have been framed in an architectural moulding like the one which now holds it, so that it could be incorporated into a hypothetical tier of further painted decoration above the wooden panelling.

NG 3070 Tura; details of (top) current, and (bottom) previous frames

The previous pierced and layered frame, which may have been given to it by Sir Austen Layard, resident of Venice and collector of early Italian paintings, is an extraordinary work of art in its own right, but so assertively ornamental that it conflicted with Tura’s own bizarrely decorative vision of Apollo’s attendant. The spiny, toothy dolphins which form the canopy, arms and pedestals of Calliope’s throne are rendered (as it were) toothless by the flamboyantly scrolling tendrils of flowering vine which rampage so close to them, and even Calliope herself is somewhat muted.

Juan de Valdés Leal

NG 1291 Valdés Leal (1622-90), The Immaculate Conception of the Virgin, with two donors, c.1661, o/c, 189.7 x 204.5 cm., in previous 19th century reproduction Baroque Spanish-style frame, with fluted back edge; stopped-channel fluting on top edge with leaf corners; frieze repainted in red with applied scrolling foliate-&-flower corner-&-centre panels; centred imbricated leaf bud at sight edge

NG 1291 Valdés Leal, The Immaculate Conception of the Virgin…, reframed in 17th (or early 18th century?) Baroque Italian frame; concave profile with torus at top edge; spiral leaf on the torus; stylized cross-cut acanthus leaf in the hollow; finished with parcel-gilding and polychromy, with a pale grey back edge, red band below the torus and blue-grey inside the spiral leaf (this latter may contain Prussian blue and therefore date post-1704)

Like many costume dramas on film which remain resolutely of their own time – for instance, the notorious 1940 adaptation of Pride and prejudice (with crinolines, eyeliner and archery) – some reproduction frames resist any suspicion of the passage of time, or indeed of any close connection with the century they are supposed to represent. The hard-edged carving and cheerfully Formica-red surface of the frieze certainly kept the previous frame of this celestial vision firmly grounded on modern earth.

NG 1291 Valdés Leal, detail of current frame

The frame which replaces it, although Italian, shares features of Baroque Spanish woodwork – its large-scale, fluidly carved motifs, like the curvaceous acanthus leaves in the hollow; the use of spiral leaves as a contour moulding; and an imaginative employment of polychromy. It may possibly originate in Naples, which was ruled by the Spanish crown from the early 16th to the early 18th century, and saw a diffusion of influence through craftsmen travelling between Spain and the kingdom of Naples. It provides a shimmering halo of gold around the painting, and picks up the reds and blues of the composition.

NG 1291 Valdés Leal, detail of current frame undergoing restoration

Framed from Gallery stock

Henri-Joseph Harpignies

NG 2256 Harpignies (1819-1916), A river scene, c.1850-70, o/c, 21 x 23.2 cm., in previous mid-19th century reproduction Louis XIV-style wide ogee frame, decorated overall in compo; with flowered back edge, foliate-&-strapwork Bérainesque ornament on a faux- ‘lace’ ground; slightly projecting corners; leaf-tip sight edge; inlay; converted for a glazing door

NG 2256 Harpignies, A river scene, reframed in a NeoClassical scotia pattern, probably British, from the second half of the 19th century; convex profile with stepped top edge; beads at back edge; gilded and patinated

Harpignies’s landscapes are realistic, rather than Romantic, but they are also classically composed; he was influenced by travelling through the Italian countryside, by his friend Corot, with whom he travelled, and by the Italianate landscapes of Poussin and Claude. The frame in which this work arrived in the Gallery collection almost flattened the realism out of it, and was besides in a parlous state, having lost most of one corner, and with the other three brittle and cracked. The solution was a Gallery stock frame, which, with its sparse ornament and deep scotia, removed all distraction, and gave an energetic thrust to the deep recession of this little scene. Now, the strong diagonals which organize tree branches, hill slope and reflections are emphasized by the mitres, and point the viewer’s attention more forcefully to the distant figures where these lines meet.

**********************************************************

Supporters 2012–2013

Miss Elizabeth Floyd

Dr David R. Ives F.R.C.P.

James & Clare Kirkman

Timothy & Madeleine Plaut

Sir Hugh & Lady Stevenson

Sir Angus & Lady Stirling

**********************************************************

[1] Lionel Abel, Lucien Pissarro & John Rewald, Camille Pissarro: Letters to his son Lucien, p. 135, 9 September 1889