National Gallery: building a Gothic polyptych frame

This is the story of how the panels of an enormous 14th century altarpiece, which were purchased by the National Gallery in 1857 as twelve separate paintings, have been united again in the most authentic replica Gothic polyptych frame to be created in the last six-and-a-half centuries [1].

The history of the altarpiece

This work, the central panel of which depicts the Coronation of the Virgin, was completed in 1370-71 for the high altar of San Pier Maggiore in Florence, at that time a church of major importance in the city, first built in the 5th century, rebuilt in the 11th, and attached to a long-established and wealthy Benedictine convent. The large Gothic church for which the altarpiece was executed was finished in 1352, so was still relatively new and shiny.

The church of San Pier Maggiore in 1370-71 (from the image in its own altarpiece), and its position relative to the Duomo on a map of Florence by Pierre Mortier, 1704, The Map House

Its status and congregation ensured that mercantile and noble donors commissioned works from artists such as the Master of St Cecelia, Botticini (his Assumption of the Virgin also holds an image of the church), and Granacci (he too painted an Assumption of the Virgin in c.1515 for the Medici). The National Gallery’s Coronation of the Virgin was commissioned by the Albizzi family, prosperous wool merchants and exporters from Arezzo who moved into banking and politics, and for whom such a large and spectacular altarpiece (nearly five metres high) symbolized their temporal wealth and power as much as it signalled their faith [2].

Jacopo di Cione workshop (fl.1365-c. 1398-1400), panels of the San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece arranged without frames in the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery from 2018. Photo: Caroline Campbell

The panels are assumed on stylistic grounds to have been painted by Jacopo di Cione and his workshop; the original, now vanished frame, and possibly the compositions of the paintings as well, were designed by ‘Niccolò the painter’ (Niccolaio dipintore) who is taken to be Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, an artist who worked on other projects with Jacopo. He spent fourteen recorded days on the San Pier Maggiore altarpiece, for which Ser Taddeo – probably an attorney, and in charge of the commission and its finance – paid him twelve gold florins. This was in 1370; the next year Ser Taddeo was involved in collecting payments he had made for materials and other costs to be refunded to him by the workshop, and which are all noted in his daybook, like the money paid to Niccolò the painter. These notes convey more information about the creation of the altarpiece overall:

1371

‘L’opera di san Pier Maggiore dee dare, paghai per lei:

… – per rechatura Io colmo della tavola da casa Matteo di Pacino, s. I d. 6…

– e per rechare e portare la predella a santa Maria Nuova a vernichare, s.3….

– per bollette e chiovi per chiavare i colonelli e folgle [sic; ‘foglie’ ], s.5…’‘The opera of San Pier Maggiore has to give me back what I have paid out for them:

… – for collecting one panel of the altarpiece from the house of Matteo di Pacino, 1 soldi 6 denarii…

– and for carrying and delivering the predella to Santa Maria Nuova for varnishing, 3 soldi…

– for nails and pins to fasten on the small columns and leaf ornaments, 5 soldi…’[3]

Matteo di Pacino (fl.1359-74) worked in the circle of Andrea and Jacopo di Cione, and was either helping to paint the various panels, or (as he was also a miniaturist) may have been engaged on the mordant gilding of the robes throughout the altarpiece, the sgraffito (e.g. on the cloth of honour behind Christ and the Virgin at the centre), or perhaps the punchwork.

The fact of a panel being worked on elsewhere, as well as of the predella being sent to Santa Maria Nuova for varnishing, confirms that the whole great polyptych was, like the modern replica frame, made in sections which could be transported through Florence fairly easily, and would then be assembled on the high altar of the church. Each panel would have had its integral frame, carved, attached, gesso’d and gilded all in one with the pictorial surface. The nails which had been ordered were of two sorts, which seem to have been heavier-duty nails or screws for fastening the main elements together, and lighter metal pins for securing barley-sugar columns to the façade, as well as the foglie – what are either the leaf capitals or the leaf- like crockets which often follow the finial spires or the pitched tops of the upper panels in a polyptych.

Unfortunately, not enough of the records survive to show how much in total all the participants in the making of the altarpiece were paid, nor in whose workshop the frame was constructed, carved and gilded (the painter isn’t named, either).

Lippo Vanni (fl.c.1340-75), Trompe l’oeil polyptych of the Madonna & Child with saints, 1360s, fresco, and detail, Martinozzi Chapel, San Francesco, Siena. Photo: Sailko

The finished, framed work would have looked something like the trompe l’oeil altarpiece painted in a stone niche in the Martinozzi Chapel of San Francesco, Siena, by Lippo Vanni less than ten years earlier. It would have been larger, of course, with an extra tier of panels and detailed scenes from the life of St Peter in the predella, rather than small figures of the Virgin, Christ and St John surrounded by saints or prophets. It would have had the same buttressing pillars – possibly with the triangular-shaped section which can be seen at either side of Vanni’s painting – and which would have been screwed with iron stanchions to the altar, to help support the immense weight of the whole polyptych. Ian McClure notes that:

‘While there is evidence (such as the fixing of battens at only one point on each vertical plank of the painting) that altarpieces were constructed to allow small movements, it seems likely that the relative stability of environmental conditions within the church or chapel mitigated the buildup of tension and stress, which could result in cracking and splitting. Elements of the San Pier Maggiore altarpiece, however, were probably glued, dowelled, and nailed together with battens—procedures that produced a very rigid structure to counter the artwork’s size and weight. [4]’

Ser Taddeo’s notes reveal that the complete and massive polyptych was furnished with a curtain:

1371:

‘… – per 24 anellini per la cortina, a d. 6 l’uno, s.12.

… – per spagho rinforzato per al cortina, s.6.’‘… – to 24 small rings for the curtain, at 6 denarii each, 12 soldi.

… – to reinforced cord for the curtain, 6 soldi.’

Sodoma (Giovanni Bazzi; 1477-1549), St Benedict gives posthumous absolution to two nuns, from Episodes from the life of St Benedict, c. 1505-08, detail showing painted altarpiece, Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore

This was added for liturgical reasons, but probably helped to keep the dust off as well. Sodoma shows an example of a 14th century Gothic altarpiece in the background of one of his frescos on the Life of St Benedict, with a curtain running on a metal rail fixed into the two walls of the painted apse.

Giuseppe Zocchi (1711-67), Church and Piazza of San Pier Maggiore, 1744, pen-&-ink with wash, 46.6 x 66.8 cm., The Morgan Library & Museum

In 1638 the church was partially rebuilt, with the addition of the triple-arched façade and Mannerist pediment seen in the drawing above. By 1677 the altarpiece had been moved into a side chapel and must have long lost its curtain, as it had become very dusty:

‘Capella della Rena, è in questa effigiato un incoronazione della Vergine Santissima con una quantità d’Agnoli, e di Santi di mano dell’Orcagna discepolo d’Andrea pisano ed è per quei tempi cosa di stima, ma perche è stat tenuta con poca cura, a ricevveto dalla polvere non poca ingiuria, all a quale pure si rimedierebbe col pulirla, come è stato farso in una parte ove è ritornata bellissima come se ora dalle mani dell’artefice uscisse: stette questa per molti anni all altar maggiore: a canto alla porta nell’ altro angolo è la Cappella Palmieri… [5]‘

‘..the Capella della Rena, in this is depicted a coronation of the Blessed Virgin with a quantity of Angels and Saints by the hand of Orcagna [sic], disciple of Andrea Pisano and it is a thing of esteem for those times, but because it has been kept with little care, it has received no small injury from the dust, which however could be remedied by cleaning it, as has been done in one part where it has become beautiful again as if it now came from the hands of the craftsman: this stood for many years at the high altar: next to the door in the other corner is the Palmieri Chapel…’

The church was undergoing further renovations in 1783, when a wooden column collapsed. Although it wasn’t load-bearing, the city government under Leopold, Grand Duke of Tuscany, took the opportunity in 1784 to demolish the whole building, so that a road might be run where the nave had stood, and a market opened up in front of the remnants of the 17th century façade. From the Duke’s point of view, this also removed an important church with a powerful convent and congregation from its influential position in the city.

The families who had rights in the various chapels inside the church were able to reclaim the works of art within them, and some of the contents were removed to other churches: for example, 15th century inlaid wooden cabinets from the convent are now in the sacristy of San Michele Visdomini. and Taddeo Gaddi’s Madonna del Parto (c.1355, fresco) can be found in San Francesco di Paola. Since the San Pier Altarpiece was now in the Capella della Rena, it passed, not to the Albizzi or Della Rena families, but to the Pucci, to whom rights in the chapel had fallen, and was removed by the Marchese Roberto Pucci.

The altarpiece in the National Gallery

Jacopo di Cione workshop (fl.1365-c. 1398-1400), the three main panels of the polyptych as framed together in Florence in the mid-19th century (photographed by the Gallery in 1937)

In 1846 the panels of the Jacopo di Cione polyptych were bought by the collectors and restorers, Francesco Lombardi and Ugo Baldi of Florence. They had almost certainly already been removed from their frame when taken out of the church, and probably also separated from their predella; it must have been Lombardi and Baldi who reframed them around 1850. The frame of the main tier, above, was described by Ralph Wornum [6] as an original frame which had been restored in the 1850s.

Niccolò di Pietro Gerini (fl. 1368-d.1415-27), Baptism Altarpiece, 1387, tempera/panel, centre panel 160 x 76 cm., National Gallery

In 1857 all the panels save the predella were purchased from Lombardi and Baldi by the National Gallery [7], together with other paintings such as Uccello’s Battle of San Romano, Piero della Francesco’s Nativity, and a polyptych with the Baptism of Christ by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini (above) – the proposed designer of the San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece. Looking at the frame of this altarpiece, which it still retains, its kinship with the mid-19th century frame of the main Coronation of the Virgin panels is evident, from the silhouette and surface decoration to the shallow relief panel shapes on the central pilasters. However,

‘…the passages of pastiglia on the central panel, including the roundel with the angel… are original and have not been disturbed.’[8]

This pastiglia decoration has been copied in the spandrels above the figures of the saints as part of the Lombardi-Baldi reframing, and may have been the model for the pastiglia decoration of their frame for the San Pier Maggiore panels.

Emily Mary Bibbens Warren (1869-1956), View of the entrance hall: the North vestibule, 1896-1912, watercolour, and detail, National Gallery

Here are the three main panels of the latter, still in their mid-19th century frame and further encased in a massive glazed case [9], hanging in the North entrance of the Gallery as shown in a watercolour by the British-Canadian artist, Emily Warren. Jacopo di Cione’s Crucifixion in its original frame hangs on the neighbouring wall.

Jacopo di Cione workshop (fl.1365-c. 1398-1400), panels of the San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece, NG 569, hanging in their 19th century frames, the finials &c removed, in the National Gallery

At some point between the end of WWII and the 1960s, the frame/frames underwent radical alteration, having all the finials and crockets removed, along with the Mickey Mouse ears on the pitched apex of the Coronation of the Virgin panel, the lowest mouldings of the plinth, and much of the lateral buttresses. The latter were also turned 90°, from a diagonal, triangular-sectioned form to a flat, square section, also losing their barley-sugar columns and their multi-spired finials. This may have been done as a result of losses and damage to the delicate ornaments over the previous century, and also to save space in both width and depth when hanging all the tiers together.

Like the fragmentation of the three tiers of paintings, this drastic surgery diminished the presence of the altarpiece, reducing the intended appearance of the section through a mediaeval church, flattening the volume by the change to the buttresses, and negating the vertical aspiration of the whole work, which was designed to be a representation on earth of the Celestial Church in heaven.

Reconstruction of the San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece in contemporary style of frame by Jill Dunkerton, 2009-10; coloured & montaged with the painted panels for this article

In 2009-10 Jill Dunkerton, conservator at the National Gallery since 1980 and specialist in 14th-16th century paintings, produced a provisional reconstruction of the framed altarpiece, based on examination of the separated panels. It is a structural anticipation of the 2025 frame, but is chunkier, with massive square-sectioned buttressing pillars and soaring Venetian forests of finials at the sides, all of which would probably have taken up too much room to be accommodated happily within the available space. It also, of course, takes account of the missing predella.

Jacopo di Cione workshop, panels of the San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece hanging in the National Gallery without frames from 2018. Photo: Caroline Campbell

Removal of the circumsized 19th century frames allowed the panels to be hung together in an approximation of their relationship in the original altarpiece frame; but it cannot be said that this arrangement was anything but unhappy: an orphaned relationship, excising all context and spiritual integrity from the paintings.

Making a new altarpiece frame: the sources

In 2024, Laura Llewellyn, curator of pre-1500 paintings, suggested that the project of making a complete and authentic altarpiece frame for the panels be seriously undertaken. She

‘…felt that this work “set the tone” for the rest of the trecento display – it was a display that proclaimed the fragmentary nature of the altarpiece, and by extension of the works around it… (the panels more as specimens than works of art.) Of course, many of the trecento works are fragments of bigger things, and we work hard in our displays to indicate this in sensitive and subtle ways.’ [10]

She and her fellow curator, Imogen Tedbury, selected a number of models as sources and references for the new polyptych frame, which would unite all the panels but also allow the different tiers to be exhibited separately. This meant that no single altarpiece could be copied too closely.

Niccolò Pietro Gerini (c.1340-1414) & Pietro Nelli (fl.1375-d.1419), Madonna & Child enthroned with saints, 1375, Santa Maria all’Impruneta; before war damage. Photo: Alinari Fratelli, before 1916

Gerini, Nelli, Madonna & Child enthroned, after post-war reconstruction. Photo: Peter Schade, 2024

The most notable source was the frame of the polyptych – although much smaller – painted by Pietro Nelli and Niccolò Pietro Gerini for the high altar in the Basilica of Santa Maria all’Impruneta. This was badly damaged when a WWII bomb hit the church in 1944; the church has been rebuilt and the altarpiece restored, but neither is quite what it used to be, and the best overall image of the latter is a black-&-white photo in the Zeri collection, taken around or just before the First World War (upper image, above). The contribution of Niccolò Pietro Gerini to this altarpiece is significant, given that he is credited with the design of the San Pier Maggiore frame and possibly the composition of the pictures as well.

Gerini, Nelli, Madonna & Child enthroned, detail

This frame supplied all the architectural and ornamental detail between the first and second tiers – the pitched ‘roofs’ over the arches and their roundels with leafy paterae, the run of arcaded drops above them, and then the carved vine leaves beneath the second tier of panels; the band of flowered quatrefoils at the base of the main tier was also copied. The miniature leaf capitals on the barley-sugar columns came from here; they appear, too, on the altarpiece below.

Giovanni del Biondo (fl. 1356-99), Madonna & Child enthroned with saints, 1379, with detail of lateral buttress, Sacristy, Rinuccini Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence. Photo: Peter Schade

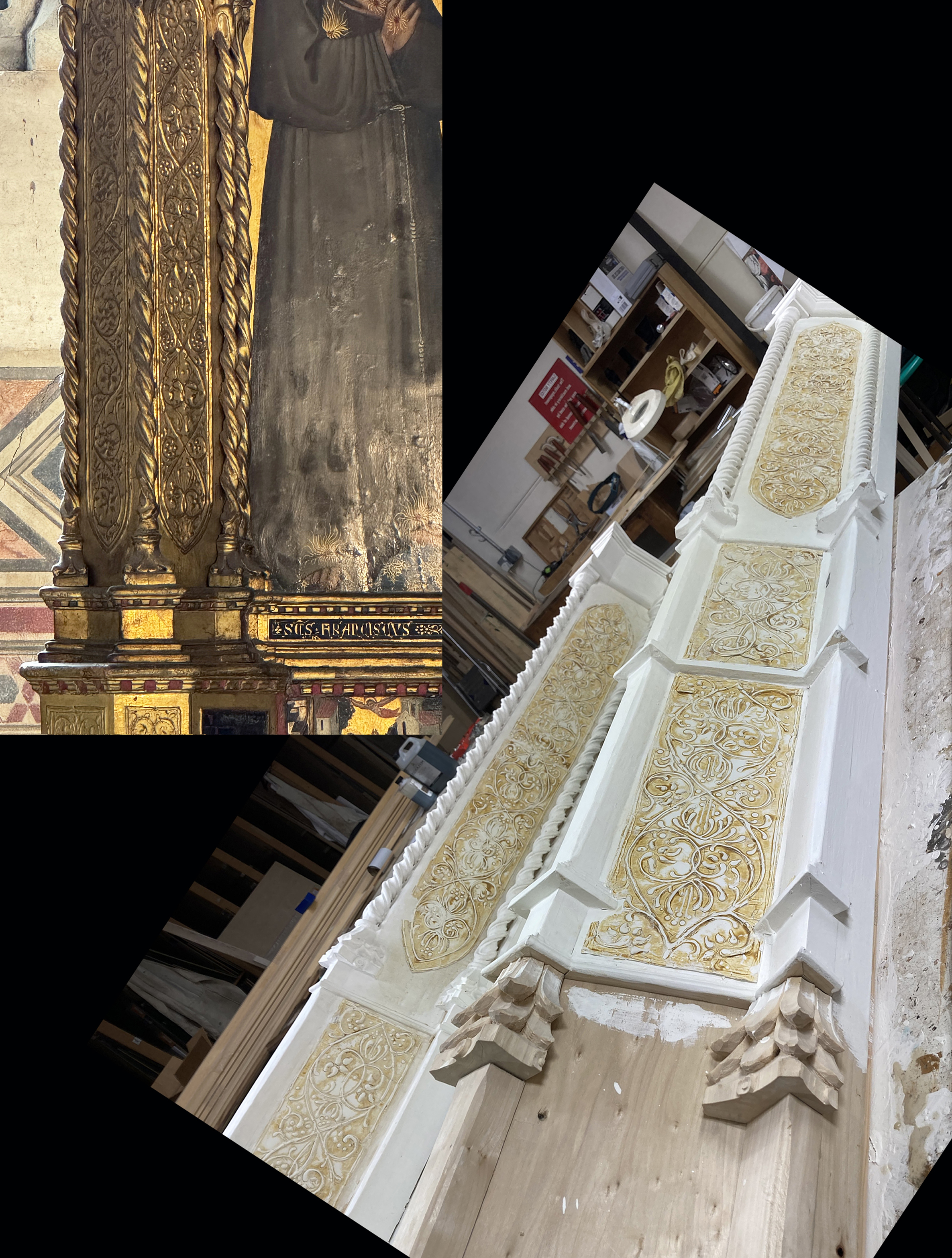

A second model, also much smaller than the National Gallery’s polyptych, was Giovanni del Biondo’s altarpiece in Santa Croce, painted only eight years later and arranged with a similar overall design. The two large lateral buttressing columns were taken from this frame; they have the requisite triangular-shaped section which slims them optically, whilst the diagonal axis of each column causes it to jut forward as if welcoming and embracing the worshipper, and breaks up the otherwise flat façade of the altarpiece. The panels of intertwining honeysuckle vines in pastiglia which decorate the buttresses were replicated, like the leaf capitals mentioned above.

Lorenzo di Niccolò (fl. 1392-1412), Coronation of the Virgin, 1402, 208 x 261 cm., and detail, San Domenico, Cortona; presented to the church in 1440 by Cosimo de’ Medici. Photo: Peter Schade

Lorenzo di Niccolò painted the third model for the high altar of San Domenico in Cortona; although it dates from thirty years after the San Pier di Maggiore altarpiece, it comes from the same Florentine circle of late 13th century painters, since Lorenzo was another collaborator of Niccolò Pietro Gerini. This polyptych (still in very good condition) helped to supply the framing of the three pinnacle panels, for which the finials at each side, but not the canopies, were copied; simplified versions of the shaped plinths were used, decorated with pastiglia instead of paintings.

Laura Llewellyn and Imogen Tedbury noted of these models that,

‘In looking to these sources we did not set out to replicate precisely what was known of the original frame and altarpiece structure. This would have been an impossible task: not only are there numerous missing elements, but the National Gallery’s panels were also reshaped by restorer Ugo Baldi in the second quarter of the nineteenth century – most notably the three panels of the upper tier have had their uppermost parts reshaped, repunched and regilded to match the shapes of the middle tier.

We made the collective decision to avoid representing missing panels with blank elements, in the case of the predella, likely roundels and possible additional upper tier (between upper and middle tiers).’ [11]

Making a new altarpiece frame: the design

Peter Schade, Head of Framing, initial drawing for new frame, July 2024

The design began, as with so many late mediaeval and Renaissance altarpiece frames, in a drawing which presented several options in a single whole. The two side panels of the main tier, for instance, were given pediments from the San Domenico altarpiece on the left, and the Santa Maria all’Impruneta altarpiece on the right. Various choices and heights for the plinths of the crowning tier were also given. Peter Schade, Head of Framing, was the third important voice in all the choices made, along with the two curators.

Coloured montages made from the different sections of the first drawing

The different sides were then flipped and joined together in Photoshop, coloured, and montaged with the painted panels, to allow the curators to have a better idea of the eventual look of the whole altarpiece. At least eight of these montages were produced, in order to find the best assembly of detail from the drawing and the different sources.

Final montages

This was the design chosen; it was Photoshopped onto an image of its future location in the Gallery, to check that it would fit physically and aesthetically into the space.

Laura and Imogen explained the parameters operating in the choice of the design and its features:

‘Where possible… we tried to convey more of how the surviving panels would have been originally seen, for example, extending the framing elements below the uppermost tier to convey the proportions of what was likely a missing additional upper tier, and bringing the middle narrative tier panels together as pairs (examination to confirm the presence of a circle drawn on the verso of one pair, noted by [Dillian] Gordon, made it clear that these pairs were originally two scenes painted on one panel, divided by a twisting column).’ [12]

Making a new altarpiece frame: the execution

The framing workshop had about six months in which to complete the carving, pastiglia work, gilding and finishing of the altarpiece frame, so that it would be ready for the re-opening of the Sainsbury Wing of the Gallery in May 2025. The original altarpiece, along with the painted panels, had been completed in around twenty months or more, with the involvement of perhaps twice as many artists of all kinds [13].

The replica frame was made by Peter Schade, Head of Framing, and François Loudwig. Like most Italian frames from the 13th century onwards it was carved from poplar wood, a hardwood with a fine, even grain, relatively easy to carve and with a smooth finish, making it very suitable as a support for both painting and gilding. The poplar in this case was grown in Wales, carefully felled and seasoned, sawn into planks, and brought to the Gallery by Jasper Meade. Although this series of photos is rather like showing a gambolling lamb in a meadow followed by a plate of lamb chops, it also charts the path to immortality for the tree.

Stephen Guest takes delivery of the load of poplar planks from Jasper Meade

Top, the back of the first tier: a pine framework holding the cut-out plywood panels; bottom: the front of the same tier, with the first runs of carved poplar wood attached to the framework

The structure of the back frame was made from pine struts and battens, but because all the painted panels had warped slightly over the centuries sheets of 3mm. plywood were used to hold them, as these would bend to follow the shape of each painting.

Peter Schade with the first tier, where much more of the carved work is coming to life

The plywood formed the ground for the decoration over the arches, and the carved ornament was fixed onto it.

Stages of carving the barley-sugar columns

All the barley-sugar columns (there are a lot of them) were carved by hand, by François Loudwig, rather than being turned on a lathe as might have been done at any time since the early 19th century; this was in order to avoid even a hint of mass-produced uniformity which might undermine the sense of this frame having being made – like its original predecessor – by hand, in a Renaissance-style workshop. Some of them are made from limewood – a softer wood, which gave a sharper finish, and allowed them to be carved more quickly.

Amanda Dickson gessoing parts of the enormous lateral buttresses in preparation for the pastiglia panels and gilding

The pastiglia panels of honeysuckle vine decoration adhered to the buttresses, with their source, top left, in the decorated buttresses of the Santa Croce altarpiece

The panels of pastiglia decoration, some of the gilding and all the patination were carried out by Amanda Dickson, ‘a gilder highly specialized in the imitation of original surfaces’ [14].

Panels of pastiglia, top, and fixed to the arches of the first tier, below

Pastiglia, used as shallow relief decoration on frames, chests, caskets, and for motifs in paintings, mainly from the 14th-16th century, is made of what Cennino Cennini [15] called ‘gesso sottile‘ – plaster of Paris which has been soaked in water for a month, dried out, enough taken of the dry purified material for the current need, soaked again in water and ground very finely. As much water as possible is then squeezed out of it in a cloth, and it is mixed with size to something Cennini compares to the thickness of pancake batter (elsewhere the consistency of thick cream is suggested). Designs can then be drawn with a brush in this mixture on a previously smoothly gesso’d surface; or a thicker version can be used with an icing bag. Its charm lies in the delicate scrolling foliage and tendrils which can be made in this way, and the soft fluidity of the slightly raised decoration it enables – so different from the deeper, more sculptural ornament with sharper edges and detail produced by carving wood.

Isabella Kocum gilding the pitched ‘roofs’ over the arches of the first tier

Much of the gilding was also completed by Isabella Kocum; here she is laying the gold leaf over red and ochre bole, or gilders’ clay, used to vary very subtly the eventual colour of the finish.

And here are the gilded buttresses, taking up a great deal of space in the workshop, and pointed at the wall of cupboards like mediaeval torpedoes. Rising behind them is the entablature of the Renaissance altarpiece frame for the Pollaiuolo brothers’ Martyrdom of St Sebastian, which was being worked on at the same time.

Peter Schade with the working design, the initial carving of the second tier, and, in the background, the carved and gilded first tier

François Loudwig carving the second tier of the altarpiece; one of the lateral buttresses, with its pastiglia panels of honeysuckle vines, is lying down across the foreground

Stephen Guest and extra helpers with the burnishing; in the foreground the St Sebastian frame again

Even more people at work on the burnishing

An army of National Gallery workers was finally called in to help with burnishing the many square metres of gilded wood, in order to leave time for Amanda to patinate the whole frame.

An agate burnisher on the workbench

Burnishing is a slow game, since the burnishing tools are small, made of very smooth stones – today, generally an agate, although Cennini recommends haematite, or,

‘failing this stone, and even better for anyone who can make the outlay, sapphires, emeralds, balas rubies, topazes, rubies and garnets… A dog’s tooth is also good, or a lion’s, a wolf’s, a cat’s…’ [16]

He then goes on to explain how to burnish:

‘Take your burnishing stone, and rub it on your breast, or wherever you have any better clothing that is not greasy. Get it nice and warm; then sound out the gold, to see whether it is ready to be burnished… And so burnish up a flat gradually, first in one direction, then, holding the stone quite flat, in the other direction… When shall you know that it is burnished properly? – the gold then becomes almost dark from its own brilliance.’ [17]

Polychromy between first and second tiers

There are also areas of polychromy on the altarpiece; for example, the long stretch of carved vine leaves (symbolizing the Eucharist) and tiny roses (an attribute of the Virgin) between the top of the first tier and bottom of the second tier of paintings has a black ground, whilst the stepped dentil moulding immediately above it has the spaces between the dentils painted alternately blue and red, like little jewels.

Polychromy on base

A similar moulding runs along the top of the plinth panel at the base of the whole work, which stands in for the missing predella. This panel is ornamented with carved quatrefoils, each of which is inlaid with a shaped pastiglia panel decorated with various designs (the panels can be seen laid out on cardboard with the pastiglia pieces for the top of the arches, above).

In the two illustrations above it can be seen that the gold leaf, having been burnished to a high shine, has been distressed: that is, some of the gilding has been rubbed off on the higher mouldings to simulate the wear of time. This reveals a little of the red bole lurking under the polished leaf, which warms the whole frame.

Patination of the three tiers of the frame and a buttress (top); a detail of the middle and top tiers (centre), and a close-up detail of the bottom panel (below)

Further work produces crackling of the finish, small losses through to the gesso layer or even to the wood, and judicious darkening of the surface. This patination is carried out to age the gilding, so that it is brought nearer in tone to that of the gold ground in the painted panels and creates the effect of a frame which has travelled through the centuries with the paintings it holds.

Installing the sections of the altarpiece

The not-very-mediaeval approach to art handling

The lower two tiers in place

Two of the pinnacle panels installed

Laura and Imogen summarized the result which was looked for in this reframing:

‘… the idea for the new frame was to celebrate the completeness of the object, and to help focus our visitors’ attention on how the altarpiece operates as an ensemble, rather than as a collection of fragments. Also, to use this impressive work to enhance the drama and splendour of the other late trecento and early quattrocento works in our collection… and to evoke the spectacular theatrical quality of the interior of a great Florentine basilica at the dawn of the Renaissance.’ [18]

The completed altarpiece of San Pier Maggiore, as installed in the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery in April 2025, ready for the reopening of the Sainsbury Wing in early May. Once more the visitor can see in it a reflection of the Celestial Church, full of saints and angels watching the coronation of the Virgin, with scenes from the life of Christ above, and the Trinity, accompanied by more angels, at the apex. Once more it is a work to the glory of God, aspiring to the heavens.

**************************************

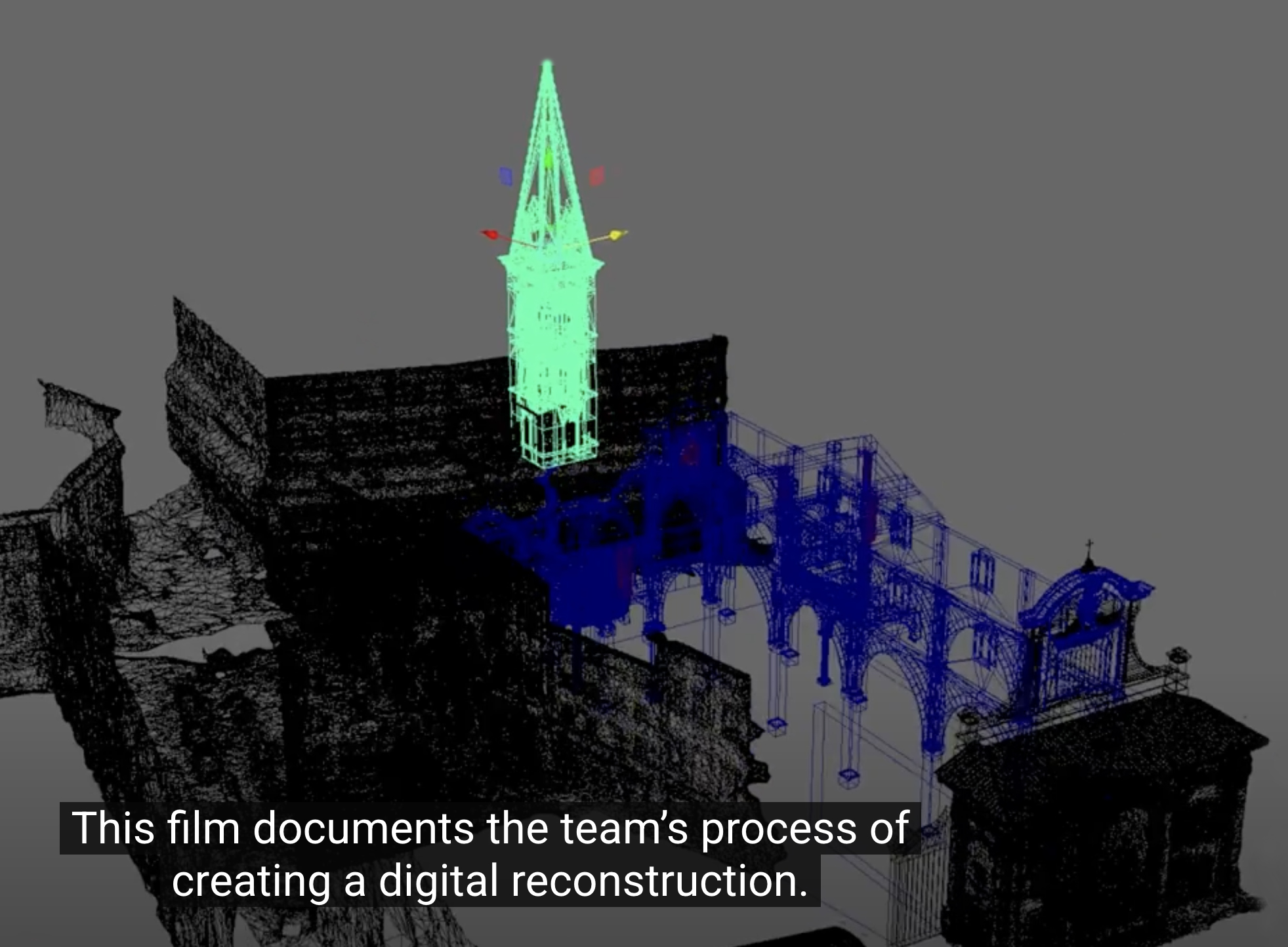

Reconstructing the church of San Pier Maggiore

In 2015, the National Gallery and Cambridge Unversity made a short video on the digital reconstruction of the church of San Pier Maggiore, which you can see here:

This has since been expanded (by the universities of Cambridge, Exeter and Florence working in collaboration) to an app which can be downloaded and used in the presence of the altarpiece in the National Gallery, or in Florence, in the vicinity of the vanished church, to experience the digital ghost of the building and the polyptych within it:

**************************************

[1] The National Gallery does not possess the predella panels of the altarpiece, of which five are in other museums: The arrest of St Peter, Rhode Island Museum of Art, Providence, Liberation of St Peter, Philadelphia Museum of Art, St Peter raising the son of Theophilus, The chairing of St Peter at Antioch, and The crucifixion of St Peter, all three Vatican Pinacoteca; whilst the location of The last meeting of SS Peter and Paul is unknown. There may also have been further painted panels, images on the buttresses, and insets of roundels between the tiers

[2] The Palazzo Albizi [sic] is on the Borgo degl’Albizi, practically across the road and fractionally north-west from where the church of San Pier Maggiore once stood; it was by location as well as importance their family church

[3] Florence, Archivio di Stato, Conventi soppressi, San Pier Maggiore, vol. 50, Ricordanze dal 1369 al 1380, c.6; quoted from H.D. Gronau, ‘The San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece: a reconstruction’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 86, no 507, June 1945, p. 144

[4] Ian McClure, ‘The Framing of Wooden Panels’, in The structural conservation of panel paintings, papers given at a symposium, J.Paul Getty Museum, 1995, pp. 433-34

[5] Francesco Bocchi & Giovanni Cinelli, Le bellezze della città di Firenze, 1677, p.353-54; see the Internet Archive. The Palmieri Chapel was where Botticini’s Assumption of the Virgin hung, now NG 1126 in the National Gallery; thought by Bocchi and Cinelli to be by Botticelli

[6] Keeper of the National Gallery from 1854-77, under the Director, Sir Charles Eastlake

[7] The parts of the altarpiece were measured in 1859:

‘Sight size of centre compartment to point of Gothic arch 7ft 9 inches x 3 ft 9 inches.

Side compartments each – 5ft 6 inches x 3ft 8inches

Measurement including Gothic frame 9 ft 6 ½ inches x 13 ft inches.

570, 571, 572- Measurement including Gothic frame 3 ft 7 ½ inches x 1 ft 8 inches.

Light of 570, 571, 572 – 2 ft 10 in x 1ft 3 inc.

Light of 573, 574, 575, 576, 577, 578 each 3 ft 1/2 inc x 1 ft 7 inc.

Measure including gothic frame left blank.

Compartments of the large picture protected with glass in 1858’.

(NGA: NG10/3 Manuscript Catalogue 359-663 P; Louisa Davey, Frame Dossier NG 569)

[8] Britta New et al., ‘Niccolò di Pietro Gerini’s Baptism Altarpiece: Technique, conservation and original design’, National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 2012, vol. 33, pp. 27-49

[9] In 1864 the frame was restored, and the glazed case added in 1871 – presumably to protect the fragile finials and crockets (Catalogue of paintings, 1864, Ralph Wornum; NGA: R.N. Wornum diary, 1855 – 1877, NGA 2/3/2/13; Louisa Davey, Frame Dossier NG 569)

[10] Laura Llewellyn & Imogen Tedbury, ‘Curatorial notes on the San Pier Maggiore altarpiece frame, 2025’

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.; and see Dillian Gordon, National Gallery Catalogues: The Italian paintings before 1400, 2011

[13] Gronau, op. cit., p.140

[14] Peter Schade, in The National Gallery Review of the Year: 2016-2017, London 2017, p. 31

[15] Cennino Cennini (fl. c.1370-1440), Il libro dell’ arte, c.1395-99, translated by Daniel Thompson as The Craftsman’s Handbook, published by Yale University Press in 1933 and republished by Dover Books in 1954 & 1960. The relevant sections are reproduced on The Frame Blog (‘National Gallery, London: a Venetian pastiglia frame‘), courtesy of Dover Publications, Inc., with illustrations courtesy of Michael Hilliard of Perceval Designs

[16] Ibid., p.82

[17] Ibid., p.84

[18] Llewellyn & Tedbury, notes; op. cit.