A Victorian Obsession…with frames

by The Frame Blog

from the exhibition A Victorian Obsession: The Pérez Simón collection at Leighton House Museum (14 Nov. 2014 – 29 Mar. 2015)

A Victorian Obsession: The Pérez Simón Collection in the Silk Room, Leighton House Museum (detail). Photo: Todd White Photography

In the 19th century the Pre-Raphaelites, the Olympians and the Aesthetes were supported by a body of cultivated, middle-class entrepreneurs, who wanted to assemble contemporary art collections to rival the Old Masters owned by the upper classes. There were T.E. Plint, the stockbroker, William Graham, the wine merchant and MP, George Rae, the banker, and Frederick Richards Leyland, the shipping magnate, amongst others. In the late 20th and early 21st century there is Juan Antonio Pérez Simón, businessman and art collector, who has assembled a group of Victorian and Edwardian paintings which would have made Lord Leverhulme (1851-1925), the soap grandee and founder of Lever Brothers, feel completely at home.

Fifty-two paintings from this collection have come to Britain, a number for the first time in many years, and are being exhibited – with satisfying appropriateness – in Leighton House, the extraordinary small palace of art built for Frederic, Lord Leighton, from 1864 by the architect George Aitchison. They are by artists who were contemporaries and colleagues, connected with, vying with and often inspired by each other; and a notable aspect of the paintings as a group is the individuality, inventiveness and beauty of many of their frames.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Fatima, 1862, watercolour & gouache, 31 x 10 9/16 in (78.7 x 26.8 cm)

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Fatima, 1862, watercolour & gouache, 31 x 10 9/16 in (78.7 x 26.8 cm)

The earliest of these in the exhibition belong to the Pre-Raphaelites’ innovatory period of frame design, and its influence upon their friends and followers, such as Burne-Jones and Arthur Hughes. Burne-Jones’s Fatima is a watercolour and gouache, reminiscent in its subject matter, composition and proportions of his even smaller pair of literary heroines – Clara von Bork and Sidonia von Bork (1860) – in the Tate; it may originally have been framed in the same style as the Von Bork pair as well.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Sidonia von Bork, 1860, watercolour & gouache, 131/8 x 6¾ in ( 33.3 x 17.1 cm), Tate

Burne-Jones’s father was a framemaker in Birmingham, and he naturally made his son’s first frames. However, the designs introduced by Ford Madox Brown and Rossetti, who were in one of their most imaginative phases at this period, ‘…baffled the skill of his small workshop’, as Burne-Jones’s wife put it[1], and the arrangement was tactfully terminated. Burne-Jones’s The heart desires in the current exhibition (from the Pygmalion series) has a much later version of this frame, which, although greatly darkened, still looks in fairly good condition. But the pair to the work above, Clara von Bork, had so badly constructed a frame that it has had to be given a new replica outer moulding, the band of three compo runs of tiny bay leaves having crumbled away. If Fatima (painted two years later than the Von Borks) had the same design, this may have been its fate, too. At any rate, its current setting, with a smooth gilded insert instead of a gilded and butt-jointed oak mount, and a black outer frame with gilt flutes, is similar to patterns used by Ford Madox Brown, and to slightly later studio frames; it may perhaps be a reframing by Burne-Jones, or by an early purchaser.

Arthur Hughes, Enid and Geraint, 1863, o/c, 10 5/32 x 14 5/8 in (25.8 x 37.2 cm)

Arthur Hughes’s painting, also of the early 1860s, is similarly indebted to F.M. Brown and Rossetti; it is framed in a version of what Brown referred to as ‘Rossetti’s thumb-mark pattern’[2], around a shallow-arched, bevel-edged inscribed mount extremely close to those Brown himself habitually used. Hughes is notable for his own contribution to Pre-Raphaelite frame designs, which generally include ivy leaves in various arrangements; these would have been just as appropriate for Geraint and Enid in a wood, but perhaps he needed a rather more affordable frame at this point. Perhaps, equally, this may be a reframing by an owner or dealer.

Rossetti’s design, whilst simple and relatively cost-effective, was very versatile and could be adapted to many subjects. Rossetti himself used it mainly for his series of small bust-length portraits of women, set in shallow decorative spaces, where the geometric ornament of the moulding complemented the flat, tapestry-like abstraction of the painting. Used here, for Arthur Hughes’s work, it takes on the overtones of a castellated wall, threatening the ideal love of the Arthurian couple, as if with a premonition of the trials they were to pass through.

Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), Returning home from market, 1865, o/panel, 15 15/16 x 22 ¾ in (40.5 x 56.8 cm)

With the remaining 1860s frames in the exhibition, we move from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Olympians and Aesthetes. First is Alma-Tadema, with one of his earlier Roman paintings which replaced the Merovingian subjects he had initially preferred. Whilst honeymooning in Italy in 1863 he had discovered the lure of ancient Rome and an archaeological interest in depicting how daily life might actually have appeared to the Romans themselves. Returning from market transforms the mundane activities of 19th century life by remaking them in Roman guise – and with the appropriation of costume, buildings and accessories from the time of Augustus come the frames, decorated to match. This work is painted using the rather warm, earthy palette Alma-Tadema had preferred for his Merovingian pictures, and in contrast to the bright, cool sunlight and Mediterranean skies of his later work (even Pheidias and the frieze of the Parthenon of 1868, Birmingham MAG, although obviously an interior scene, is still painted in very warm, subdued tones); so that this picture sits on the cusp of his changing style.

Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), Returning home from market, 1865, detail

The frame is also different from what we tend to think of as an Alma-Tadema design, which is generally either an aedicular or a tabernacle frame, plus or minus supporting modillions, base and pediment, or a linear gilt frame with a deeply canted, almost triangular section, painted with a run of dog’s-tooth ornament in black. There are a few other idiosyncratic moulding frames, often with incised decoration (e.g. continuous lotus buds); but the pattern of Returning home from market is particularly singular in its design of gold buds and waterlily flowers on a polished ebonized rail: it too seems poised on the cusp of a changing style. The gilded decoration perhaps relates to motifs taken from the Pompeiian pages of Owen Jones’s A grammar of ornament (published 1856), as does the combination of gold on a black ground; it is extremely attractive, and the perfect foil to this painting.

Edward Poynter, Andromeda, 1869, o/c, 20 3/16 x 14 1/16 in (51.3 x 35.7 cm)

Edward Poynter, another of the Olympians (Victorian classicizing painters), is represented here by the small Andromeda of 1869. Poynter was almost as inventive a designer of appropriate classical frames for his work as was Alma-Tadema, and the ‘Watts’ frame of Andromeda is rather unexpected – especially since the swirling abstracted composition of the painting has much in common with Diana and Endymion (1901, Manchester CAG; identical frame to The cave of the storm nymphs, 1902 ). Andromeda, however, has a butt-jointed ‘Watts’ frame (named by association with the artist G.F. Watts), and appears to be original; it may pre-date Poynter’s aedicular frames, or be the choice of a collector. The ‘Watts’ frame derives from an Italian Renaissance cassetta, with a carved outer edge of acanthus leaves, a sight edge of husks or other small ornament, and a frieze which might be either plain or decorated with punchwork. It works well with the painting, complementing its flat, decorative qualities, and introducing a slight classical reference; the relative width of frame to canvas also gives a broad area of transition from the stormy world of the mythological subject to the Victorian interior where it would have hung.

Albert Moore (1841-93), A quartet: A painter’s tribute to the art of music, 1868, o/c, 24 5/16 x 34 15/16 in (61.8 x 88.7cm)

The last work from the 1860s with an artist’s frame is Albert Moore’s extraordinary exercise in the evocation of musical rhythm and harmony, A quartet… of 1868, which is as deliberately flat and decorative as Poynter’s Andromeda, and even more devoid of narrative input. Moore is a powerful and immensely capable artist, with an exquisitely developed sense of colour and line, who has unfairly lost out in the celebrity stakes to his pupil and one-time colleague, Whistler. It was Moore who dragged Whistler into life-drawing classes, and Moore who interested him in the principals of design and composition underlying the Japanese prints he (Whistler) was already collecting, rather than the detritus of japonaiserie which marks his Lange lijzen of the six marks (Philadelphia MA), The golden screen (Freer), and the Princesse du pays de la porcelain (Freer), etc. (all 1863-65, and all in frames influenced to some extent by F.M. Brown and Rossetti). Moore and his family were very interested in music[3], and his exploration of the interconnection of art and music may also have influenced Whistler’s series of titles for his work – the ‘symphonies’ and the ‘nocturnes’.

Moore had, by this time, already painted The Shulamite (1864-66, Walker Art Gallery) and A musician (1865-66, Yale Center for British Art), in both of which the subject – a group of auditors to a performance of, in the one, a poetic incantation, and, in the other, the music of a harp – was reflected in a composition of rhythmically disposed figures against a background of horizontal bands. The flow and interruption of line was enhanced or undercut by a harmony of colours, and by intervals of space and ornament on the frame. A musician was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1867, the same year that Whistler showed Symphony in white: No 3.

Albert Moore, A quartet: A painter’s tribute to the art of music, 1868, detail

Albert Moore, A quartet: A painter’s tribute to the art of music, 1868, detail

Around this time, Moore’s experiments with frames, including the setting of The Shulamite where paired reeds were set at irregular intervals across the frieze, became more formalized. On the frame of Pomegranates (1866, Guildhall Art Gallery), some of the reeds are broken into lines of beading and some into classical bead-&-bobbin mouldings, and in the frame of A quartet… we can see that this pattern is further elaborated – as if to reinforce the ideas of rhythm and interval, expressed in the painting, by reproducing them in three dimensions on the frame. The varied ornaments – beading, nicked astragals and bead-&-bobbin – create different intervals in relationship to each other, just like the figures, the arrangement of colours, the pots on the shelf and the lines of heads and feet, in a carefully-orchestrated overall effect. Moore has turned the whole work of art into an analogue in carved wood and paint of a musical performance, in an incredibly sophisticated and mathematically intelligent piece of prestidigitation.

The analogy of music and art is taken up by J.M. Strudwick, one of the second wave of Pre-Raphaelites. He was born the year after the Brotherhood was formed, in 1849, and became an assistant to J.R. Spencer Stanhope, his uncle and also Evelyn De Morgan’s. Spencer Stanhope had a house in Florence where he spent half the year, moving there permanently in 1880, and he commissioned frames from local carvers, who preserved traditional skills and were probably less expensive than the few good carvers remaining in London. Evelyn De Morgan and Strudwick also acquired their frames in Florence, as the family resemblance of settings on work by these three artists illustrates: they tend to combine several orders of shallow but crispy-carved ornament in an opulent moulding decorated across the whole rail, giving a slightly exotic Renaissance richness to the paintings they contain.

J.M. Strudwick (1849-1937), Song without words, 1875, o/c, 29 ¼ x 39 5/16 in (74.3 x 99.8 cm)

Strudwick also worked as studio assistant to Burne-Jones, which may explain the use of a Pre-Raphaelite reed-&-roundel frame on the earlier of his two paintings in the Pérez Simón exhibition. This is the 1875 Song without words, Strudwick’s only acceptance in the Royal Academy throughout his career. It uses the natural world and the medium of birdsong to evoke the emotional power of music, rather than the more abstract tools of harmony and line preferred by Moore. The flat simplicity of the frame and the texture of the gilded oak marry well with the tapestry-like surface detail of the painting.

J.M. Strudwick (1849-1937), Passing days, 1878, o/panel, 14 13/16 x 44 15/16 in (37.6 x 114.2 cm)

J.M. Strudwick (1849-1937), Passing days, 1878, o/panel, 14 13/16 x 44 15/16 in (37.6 x 114.2 cm)

The second of Strudwick’s paintings, Passing days, was painted three years later, and shown at the Grosvenor Gallery, that temple of the Olympian and Aesthetic, in 1878. It followed his submission to the Gallery of Love’s music in 1876; this was another evocation of a musical theme, and like Passing days had a long frieze-like composition; it also had a gilt oak cassetta frame with roundels, evidently based on those of Brown and Rossetti. Passing days, however, is an allegory of time and mortality, and it is set in what may be the first of Strudwick’s Florentine frames.

J.M. Strudwick, Passing days, 1878, detail

J.M. Strudwick, Passing days, 1878, detail

The difference in treatment of this frame from Pre-Raphaelite patterns is instantly clear: Strudwick was still only 29 and hardly launched on his career, but he was using a frame laden with extravagant decoration. In Britain only artists such as Holman Hunt could afford a setting quite so heavy with carving, and even Leighton, princely in revenues though he was, tended to use compo for frames with a larger area of ornament. There was a downside to ordering frames from Florence for use in London, however: it was difficult to rouse the carvers to the importance of deadlines when you were far away and exhorting them in a foreign language. Evelyn De Morgan eventually settled in Florence, painted most of her work there, and had it shipped home at the outbreak of the First World War; but Strudwick stayed in England, and by 1896 was writing apologetic letters to a patron about a missing (carved) frame:

‘I used to have my frames from Florence… but I found it troublesome dealing with people so far away… My trouble with the London man is hardly less.’[4]

Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830-96), Crenaia, the Nymph of the Dargle, 1880, o/c, 30 ¼ x 10 11/16 in (76.8 x 27.2 cm)

Leighton’s Crenaia, painted two years after Strudwick’s Passing days and two years after he himself was knighted, and smaller in size than the younger man’s painting, has a classicizing cassetta decorated in compo, which would have been infinitely easier to organize and pay for – especially since this continuous decoration (alternating palmettes and anthemia, or honeysuckles) was one of Leighton’s regular patterns.

Leighton, Crenaia, the Nymph of the Dargle, 1880, detail

Nevertheless, it makes a very rich and appropriate border for a small painting, giving it importance and focus by its sheer width, relative to the canvas (the width of the frame is much more than half that of the painting). Within this wide margin, the plain sight and top moulding and the very low relief of the ornament ensure that the figure is never overwhelmed by the frame. The ornament at the same time emphasizes that she is a classical nymph, the presiding spirit of a river, rather than a slightly under-clad English girl.

Leighton seems to have used linear moulding frames, decorated with compo ornament (as above), occasionally with carving and frequently with painted motifs, for quite a long period, only beginning to design classicizing aedicular and tabernacle frames in the 1870s. These earlier styles can seem awkward, both in proportion and ornament – for example, the frame of the large frieze-like Daphnephoria (1876) in the Lady Lever Gallery, which is too flimsy for the size of the painting, and decorated with small hairy hooves in the bottom corners.

Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830-96), Greek girls picking up pebbles, 1871, o/c, 35 1/16 x 51 in (89 x 129.5 cm)

As he settled into the business of creating appropriate settings for his classical subjects, however, he adjusted the proportions, and arrived at a satisfying and fairly plain aedicule, with small Ionic capitals and fluted pilasters: e.g. Clytie, now hanging at Leighton House as part of the permanent collection . At some point in the 1880s, however, he developed a frame with a different capital – an Ionic order with a rounded top, based on capitals from the temple of Apollo at Bassae, and replicated by the architect C.R. Cockerell on the façades of the Ashmolean Museum and Taylorian Institute in Oxford, and the Sun Fire Office in London (demolished). This became Leighton’s exclusive design, used alongside the earlier, standard Ionic order, for the rest of his life.

The frame of Greek girls picking up pebbles is not consistent with these designs, nor with the relatively early date for a painting by Leighton in an aedicule. It may be a replica, or an adaptation. The painting was in the collection of Joseph Chamberlain, the MP, but it is not clear how it was then framed; however, by analogy with Clytemnestra (c.1874), Crenaia or Psamathe (1880), a linear moulding frame seems more likely. The roundels on the frieze of the entablature are very similar to those of Daedalus and Icarus (exh.1869), but again that has a linear moulding frame.

Frederic, Lord Leighton (1830-96), Antigone, 1882, o/c, 243/16 x 201/13 in (61.4 x 51 cm)

Leighton’s Antigone, like Poynter’s Andromeda, is in a ‘Watts’ frame. A popular choice for contemporary portraits in the last quarter of the 19th century, this design works equally well for what could be seen as a classical portrait. Given the darkness of the subject, in the approaching death of Antigone, the simplicity of a cassetta with few decorative mouldings and a fairly wide, plain frieze is particularly suitable.

Antigone is, in its sparseness, at probably the furthest remove as a classical subject from Alma Tadema’s The roses of Heliogabalus, which forms the apogee of this exhibition, with a room to itself, and a collection of photographs and drawings used by the artist in its creation.

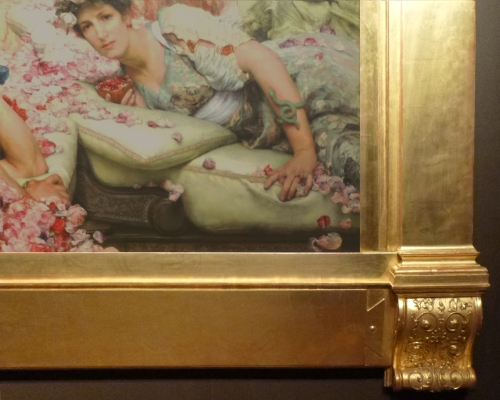

Lawrence Alma Tadema (1836-1912), The roses of Heliogabalus, 1888, o/c, 52 ¼ x 84 3/8 in (132.7 x 214.4 cm)

Just as he researched the interiors, furniture and clothing of his chosen period, endeavouring to represent them with archaeological accuracy (his painting of Pheidias… was pioneering in showing the frieze of the Parthenon painted in realistic colours), Alma-Tadema took great care over his frames – as can be seen in the gold and ebonized setting of Returning from the market (above). He painted several interiors showing Roman ‘art collections’, with rather unlikely easel paintings bordered in a variety of frames, including a decorated aedicule and a triptych; and the actual settings for his pictures are as classical in spirit as Leighton’s. The plain, temple façade design used for The roses of Heliogabalus was very flexible, appearing in large works with a landscape format, as here, and also in an upright, slender portrait format. It was used as an aedicule with a flat base, designed to be supported in some way, but more frequently as a tabernacle, with a panel flanked by modillions at the base. This panel was sometimes inscribed with a poem or quotation, and the modillions might be balanced at the top by acroteria mounted on the angles of the pediment. It was in this way that the ornament shifted towards and into the areas above and beneath the painting, minimizing distraction.

Alma Tadema, The roses of Heliogabalus, 1888, detail

Alma Tadema, The roses of Heliogabalus, 1888, detail

Alma-Tadema also adopted a stylized scroll, like a cracker or rolling pin in silhouette, which he used to carry inscriptions, titles, or his name. The right end of the scroll at the base of The roses of Heliogabalus can be seen above, with the faux nailhead ‘holding’ it to the frame. The accumulated detail of so much classical superstructure, along with the deliberately minimal presentation of the frame, the smooth gilded gesso finish and the cool, burnished gleam of the gold, created the perfect foil to the accretion of texture and the colour harmonies within the paintings themselves. The result is a heightened sense that we are looking through a classical window frame onto a scene in the past – or, at least, a still in a cinematic depiction of it. In this particular painting, the roses have started to fall, and the victims have not as yet realized that they are victims; everything is held in a moment of stasis, except the petals which drift in an innocent shower, and we wait, peering breathlessly over the gilded sill, for a further suffocating weight of flowers to follow them.

Lawrence Alma Tadema (1836-1912), couch, c.1890, mahogany & other woods, carved, turned, & inlaid, with mother-o’-pearl, brass mounts, & leather straps. Modern upholstery. Trustees of the V & A

On show in Leighton House alongside the paintings from the Pérez Simón Collection, but not part of it, is this couch, designed by Alma-Tadema around 1890 as a prop to be used in his paintings. One side has turned wooden legs in the Pompeiian manner; on the other, they are carved in Egyptian style. The Pompeiian legs can be identified in The Roses of Heliogabalus on the couch the emperor (left, in gold) is lying on, and on that of his neighbour opposite.

Lawrence Alma Tadema (1836-1912), An earthly paradise, 1891. Photo: Todd White Photography (detail)

They can also be seen in Alma-Tadema’s An earthly paradise, which is included in the exhibition, and hangs above the couch itself.

The last two frames of interest in the exhibition date from the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, when the long wave of innovatory frame design in Victorian Britain had passed its peak, and was beginning to break on the shores of a starker age, when gilding would tend to be rejected in favour of paint, and frames themselves would eventually start to be sloughed off.

J.M. Strudwick (1849-1937), Elaine, c.1891, o/c, 31 1/9 x 23 1/6 in (79 x 58.8 cm)

J.M. Strudwick (1849-1937), Elaine, c.1891, o/c, 31 1/9 x 23 1/6 in (79 x 58.8 cm)

Strudwick’s Elaine is still resolutely in the vein of Pre-Raphaelite Arthurian scenes by Rossetti and Burne-Jones. It is extraordinarily detailed, like a colour-washed engraving, and the frame is equally finely made – probably still one of the artist’s Florentine commissions, since to have had this carved in London, in the 1890s, would have been prohibitively expensive. Elaine is one of the females who, like the Lady of Shalott, fell for Sir Lancelot and ended tragically. She was known as ‘the Lily Maid of Astolat’ for her pale skin, which is highlighted in the painting through her ivory silk frock and the lilies on the floor at her feet.

J.M. Strudwick, Elaine, c.1891, detail

J.M. Strudwick, Elaine, c.1891, detail

The frame, in the same spirit, has been carved all over the frieze with a double undulating garland of lily leaves, containing small lily flowers. It is a beautifully-executed piece of work, which could hold its own with Italian frames from four hundred years earlier.

J.W. Waterhouse (1849-1917), The crystal ball, 1902, o/c, 477/8 x 313/8 (121.6 x 79.7cm)

The last frame contains Waterhouse’s The crystal ball. Although the subject is as Arthurian in derivation as Strudwick’s Elaine, this is a more contemporary enchantress, in an art nouveau Liberty tea gown, with Waterhouses’s broken, sensuous brushwork to match. The frame here is also in a particular contemporary vein: a revival of a Baroque leaf frame with an ogee section, related to the chunkily-carved torus, hollow and ogee mouldings with simple organic motifs favoured in the early 20th century by John Singer Sargent, Philip de Laszló and John Lavery. It is very effective, but it is an unabashed revival from another era, and lacks the imaginative thrust of 19th British frames – such as the pearl in this exhibition, Albert Moore’s Quartet, with its sophisticated musical setting.

Part I: Pre-Raphaelite frames > here

Part II: More Pre-Raphaelite frames > here

Part III: A final look at Pre-Raphaelite frames > here

Restoring a Pre-Raphaelite frame> here

Poetry & the frame: Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel & its altarpiece setting > here

Love in the frame: the portraits & frames of John Brett > here

What artists, critics & collectors say about frames: Part 2> here

Poetry & the frame: May morning on Magdalen Tower > here

Two Pre-Raphaelite paintings from the Leverhulme Collection> here

*************************************************************

With thanks to Leighton House Museum for hospitality, the opportunity to review this exhibition, and for the images credited above.

[1] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, 1906, London.

[2] Ford Madox Brown, letter to James Leathart, 16 Jan.1863.

[3] See Robyn Asleson, Albert Moore, 2000, p.94.

[4] Letter from Strudwick to Emma Holt, 29 June 1896, published in the catalogue of Sudley Art Gallery; information from Mary Bennett.

I have a large antique ornate frame – I’d like to get your opinion on – can I send a picture? Thanks

LikeLike

I don’t wish to seem disobliging, but I have no idea of the market value of frames; also it is always rather invidious to have to give an opinion based on photos. You would get a much more accurate opinion, I’m sure, if you were to take the frame either to your nearest large museum, or auction house. I’m so sorry…

LikeLike