Framing Renaissance portrait miniatures in Paris and London

by The Frame Blog

Céline Cachaud looks at the presentation of portrait miniatures by Nicholas Hilliard and his contemporaries, and alterations in the way they were displayed during the 16th & early 17th centuries.

Lucas Hornebolt or Horenbout (c.1490/95-1544), Henry VIII, 1525-27, watercolour on vellum, 5.3 x 4.8 cm., Fitzwilliam Museum

Portrait miniatures in watercolour on vellum are said to have been invented either in France or in England at the beginning of the 16th century, and were derived from Flemish illuminations. Indeed, the first artists known to have painted miniature portraits originated in the Netherlands: Lucas Hornebolte from Ghent, for example, settled in London in the early 1520s, and Jean Clouet from Brussels became the main portraitist at the French court at the same period. Today, most of these miniatures which have survived have lost their original settings, but – as Nicholas Hilliard wrote – they were ‘fittest for the decking of princes bookes or to put in Ieuuells of gould’ [1]. In this article, we will discuss the relationship between the function of portrait miniatures and their settings.

Gerard Hornebolt or Horenbout (c.1465-c.1541), St Louis presenting Louis XII and Anne of Brittany with St Anne holding the Virgin & Child, watercolour & bodycolour on vellum (?), 1475-1515, Musée du Louvre, Department of Graphic Arts; RF 1699-bis-recto

They first appear in religious and prayer books as early as the 15th century. The commissioning client usually appears, kneeling in front of an altar or a religious scene, showing him- or her- self as an obedient servant of God. Such miniatures are set at the beginning and the end of these manuscripts, generally close to or on the internal cover, and, when they are painted as a pair, often respond to each other, like the wings of an altarpiece. The borders of these miniatures are often gilded but can be quite plain; painted miniature scenes by Hornebout, however, may have shaped and lightly ornamented frames.

Lucas Hornebolt (c.1490/95-1544; attrib.), historiated capital with miniature portrait of Henry VIII, from letters patent for Thomas Foster, National Art Library (no MSL/1999/6), © Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Photo: AndrewRT

There were other forms of manuscript in which portraits might appear; one better-known instance is in the letters patent for Thomas Foster [2]. Here, the initial letter of the king’s name which opens the declaration has been decorated and given greater force by being employed as the frame for a miniature of Henry, painted to look as though inserted into the ground behind the letter, which has become an integral mount for it. The king, peering out through this painted frame, has much greater immediacy and reality than if his whole figure had been incorporated into the border of the MS. He is also present within his own name, giving immense force to the declaration it heads.

Later in the 16th century a new form of illumination appears, where the religious and textual context disappears in order to highlight the face of the commissioning client. At least two major examples are known.

Anonymous, Henri II and Catherine de’ Medici, post-1559, watercolour & bodycolour on vellum, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Department of Manuscripts (N.a.l. 82, internal covers)

The first one is in a book of hours commissioned by King Francis I, but passed on to Catherine de’ Medici; it is held in the collection of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The portraits show the new client with her husband, Henri II. In this manuscript, thirty-eight miniatures in all are preserved, most of them painted during the 16th century. Whilst some of them are integrated in the pages of the manuscript, most of them are pasted on the left-hand pages which would otherwise have remained unused, and were generally set into other mounts before being fixed into the book. The miniature of Henri II is held in a border which echoes a simple but three-dimensional architrave frame; the portrait of Catherine has a small trompe l’oeil moulding frame. Both are further framed in gilded linear border on the leather binding, with mitred corners and clasps.

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), Elizabeth I and François, Duke of Alençon & Anjou, 19th century facsimile from 1581 original manuscript, British Library (Fac 218)

The second book of hours, which was given by the Duke of Alençon to Queen Elizabeth in 1581, is now lost. A facsimile is preserved in the British Library and reveals that it was decorated with both portraits of the Queen and her suitor, painted on the covers.

Lucas Hornebolt (c.1490/95-1544), Henry VIII, 1525-27, watercolour on vellum, 5.3 x 4.8 cm., Fitzwilliam Museum; PD.19-1949

As portraiture gained more autonomy, miniatures emerged from the pages of manuscripts to become independent portraits. This depiction of Henry VIII is again an early example, also by Lucas Hornebolt, who served as the king’s portraitist from 1525. It demonstrates the transition from MS decoration (as in the rather later portrait on the letters patent, above) to a portrait which might be worn like a jewel and given as a favour. In this case, the painting has its own integral frame, with gilded angels in the spandrels who spin gold lines entwining the initials of Henry and Katherine of Aragon. This personal, domestic detail may suggest that this is not a gift of state, like those of Elizabeth I, below; it also combines ironically with the king’s age inscribed on the blue ground of the portrait, since at thirty-five he had already fallen in love with Anne Boleyn. The outer enamelled frame is currently under examination, to see whether it is contemporary or a later addition.

The gift of a portrait miniature was to become a popular gesture, hastened by the thirst of the French and English courts for sending diplomatic presents. The MS portraits of Elizabeth and Alençon, above, have borders which mimic the real gold frames in which they might have been set as free-standing miniatures, with garlands of imbricated bay leaves decorated with ornamental clasps. The first actual miniature portraits with movable frames, known to have been used as diplomatic gifts, are portraits of the French princes: a pair of which is preserved in the Royal Collections.

Jean Clouet (c.1485-90?- 1540/41), François, Dauphin of France (1518-36), c.1526, watercolour on vellum on card, 6.2 cm. diam., Royal Collection Trust/ HM Elizabeth II 2017; RCIN 420070

These are said to have been painted by Jean Clouet in about 1526 – very early examples of the free-standing portrait miniature. The paintings of both princes, François the dauphin and his little brother Henri, were given to Henry VIII by Marguerite of Alençon, Queen of Navarre. However, the case of this miniature, which would have been made in the form of an elaborate gold locket, is now lost. Its current setting is the generic mount found on many miniatures in the Royal Collection, which were commissioned for Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort. Interestingly, it consists of a garland of gold bay leaves, twisted with a spiral ribbon, rather like the border – painted 300 years earlier – of Hilliard’s miniatures of Elizabeth and Alençon, above; this is combined with a smaller band of bay leaves at the sight edge.

If, in the first half of the 16th century, miniature portraits were mostly produced within the royal courts, the artists were forced to search for new patronage during the religious wars which followed, and thus expand their market. As they accepted commissions from non-aristocratic clients, their prices decreased to reflect this, enabling a widening of the social classes able to have themselves depicted in miniature.

Hans Holbein (1497-1543), Portrait of Anne of Cleves, c. 1539, watercolour (gum) on vellum in turned ivory box in form of a flower, c.1580-1600, 6.1 cm. diam., & cover, © Victoria & Albert Museum, London. P.153:1, 2-1910

Isaac Oliver (1558-1617), Two young sisters aged 4 & 5 years old, 1590, watercolour on vellum on card, ivory box, 6.4 cm. diam., © Victoria & Albert Museum, London. P. 145-1910 & P.146-1910

They become pledges of affection, to be exchanged during betrothal and marriage ceremonies, or to be given within a family before a journey was undertaken. They are then frequently set into turned ivory boxes, which today comprise many of the original surviving settings. The ivory box on Anne of Cleves’s portrait, slightly later that the painting, seems to have been made either in Germany or in Britain by an itinerant German craftsman; the bottom of the box, the rim of which forms an outer frame to the portrait, is carved with a triple frill of scallops and reversed scallops, echoing the very sculptural petals on the lid and creating a sympathetic setting for the pale face and gauzy headdress within [3].

For the wealthiest clients, miniatures might also be set into jewelled pieces to be worn as pendants or brooches, thus becoming a public display of affection and or even a political statement. Several anecdotes are known which feature Elizabeth I kissing or showing her affection towards a suitor or a courtier through his image. Generally, the goldsmith in question is charged with the entire commission; he then sub-contracts the execution of the miniature portrait to a limner (much as with the commissioning of altarpieces in Renaissance Italy, where the frame came before the paintings).

François Clouet (c.1510/20-72) & François Dujardin (1543-87), pendant with the Portrait of Charles IX & of Catherine de Medici, watercolour on vellum on card, gold & enamel, pendant 6.1 x 4.7 cm., miniature 5 x 3.7 cm., with front & back covers, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. © KHM

For instance, in 1571 Catherine de’ Medici sends to her goldsmith, François Dujardin, a list of Christmas gifts which includes thirty-three portrait miniatures and illuminations, as well as a group of eight jewels, some of which are to be adorned with images of her son, Charles IX of France. It is not, unfortunately, possible to link this commission with any surviving jewel today; however, the pendant above gives us a clue of the type of object commissioned by the French queen as a gift. The back bears the interlinked initials of the king and his mother in a wreath of enamelled fruits and flowers, symbolizing the prosperity and fruitfulness engendered by the French crown. The front has the figures of Piety (with cross and bible) and Justice (with sword and scales) holding an olive branch of peace above the crown; the figures are finely worked, and the clear enamelling over a gold ground gives the scene a particular brilliance and clarity. It illustrates Charles’s motto, ‘Pietate et Iustitia’, which is inscribed on the banner scrolling around the two columns, one of gold and one of ‘silver’ – another part of the king’s iconography [4].

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), ‘The Drake Jewel’, 1579 and 1581, watercolour on vellum on card, gold, pearls, sardonyx cameo & enamel on gold, 11.7 cm. high, private collection, on loan to the V&A

In about 1581 Queen Elizabeth I gives a similar pendant to the newly-knighted Sir Francis Drake. This pendant, now known as ‘The Drake Jewel’, comprises a portrait of the queen in an enamel and gold case, with a cameo on the front. This type of jewel is similar in kind to the previous pendant by Clouet and Dujardin, which may have been offered by Catherine de’ Medici as a diplomatic gift to the Habsburg family, although ‘The Drake Jewel’ also functions at a deeper and more symbolic political level [5]. The frame of the cameo is formed of strapwork enamelled in red, holding pale blue forget-me-nots and alternating with fleurs-de-lys, set with four large rubies and four diamonds. It is a Mannerist style, related distantly to the scrolls and distorted classical ornament of a Mannerist picture frame. The facet of the jewel containing the portrait has more delicate, filigree decoration, around a band of many small rubies.

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), ‘The Gresley Jewel’, Portrait of Thomas & Catherine Gresley, c.1574, watercolour on velum; mount attrib. to Hilliard: gold, enamel on gold, sardonyx, rubies, emeralds, & pearls, 6.9 cm. high, private collection. © Philip Mould Gallery

In the 1570s Elizabeth is said to have given the newly married Gresley couple another pendant containing their miniature portraits. In both cases, Nicholas Hilliard is credited as the author of the miniatures, and – having been trained as a goldsmith – may also have designed the jewelled case belonging to it. Hilliard (1547-1619), born the year that Henry VIII died, served Elizabeth for much of her reign, and her successor, James VI & I, for much of his.

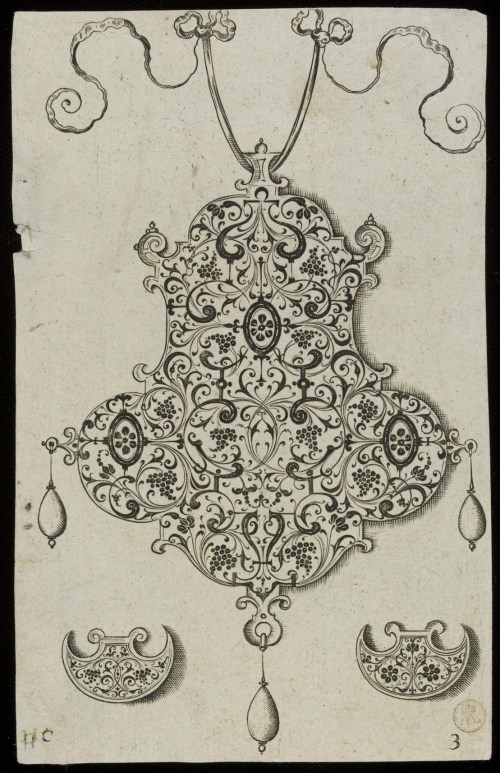

Baptiste Pellerin (fl.1542 – d.1575; attrib. here) or Étienne Delaune (1518-95; attrib. by museum), model of a reverse & a pattern for a pendant, undated, black ink & pen on velum, 3.9 x 3.0 cm., & 6. 2 x 3.3 cm., Ashmolean Museum, WA1863.133.287 & WA.1863.133.422

Both settings show some affinities with the practice of French goldsmiths: the shape of the jewel is reminiscent of patterns drawn by French artists such as Baptiste Pellerin, a goldsmith rediscovered thanks to the many engravings diffused through Étienne Delaune, to whom the drawings were previously ascribed.

Nicholas Hilliard, ‘The Gresley Jewel’, and Georg Wechter, title page of a pattern book, 1579, Renaissance ornament prints and drawings, fig 25

The structure of ‘The Gresley Jewel’ also has affinities with, for instance, designs by the Nuremberg goldsmith, Georg Wechter, whose pattern book was published in 1579. The title page cartouche of this book, with a framework of Mannerist leatherwork, pearled scrolls at the sides, morphing figures and flowers, is echoed by elements of the outer framework of the pendant [6]. The whole setting is extremely colourful, the broad enamelled band containing the portraits being painted white and holding eight rubies, alternating with blue enamel roundels, all appearing to be strung on a gold thread, like a necklace. The supporting figures are erotes with tiny gold bows and arrows, and there is a small pediment cresting the whole, and a strapwork apron at the bottom

Nicholas Hilliard, ‘The Gresley Jewel’, and Hans Collaert (c.1525/30-80), Antwerp, engraved design for a pendant, before1573, © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

The reverse of the pendant, decorated with refined arabesques and flowers, echoes – for instance – elements of the patterns designed by Hans Collaert of Antwerp. Pattern books and engravings were a rapid means by which styles, fashions and specific types of design could travel across boundaries; close trade links between Britain and the Netherlands, and the German Hanseatic League (until Elizabeth expelled it in 1597), meant that artists, craftsmen and their patterns could follow the mercantile currents.

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619; &/or workshop, attrib.), Portrait of George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, 1589, & reverse, enamel on gold & pearls, Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo, Buenos Aires

Jean Picard (workshop), front cover of a marbled maroquine bookbinding for Jean Grolier, c.1540-47, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, P-YC-1276

The reverse of these settings also testify the links between French and English artistic circles: for instance, several of the reverse sides of cases attributed to Hilliard may be compared, for instance, to bookbindings made for the courtier Jean Grolier in the 1540s.

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), Portrait, said to be Marguerite de Valois, Queen of Navarre, 1577, watercolour on velum, gold, enamel on gold & pearls, private collection. © Berger Collection

Most miniature cases are quite simple, with an oval enamelled mount patterned with painted leaves, scallops and beads, and ornamented with metal curlicues, scrolls and strapwork motifs as the hanging points for from one to three pearls. However, some of the more opulent cases show considerable mastery in the field of goldsmithing, and can be set with numbers of precious stones.

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), ‘The Heneage jewel’, watercolour on vellum, gold, enamel on gold, diamonds, rubies & rock crystal, 7. 0 x 5.1 cm., © Victoria & Albert Museum, London. M.81-1935

Queen Elizabeth offered miniature portraits to her most favoured courtiers, in a kind of political game. In return, these courtiers were expected to commission a precious case to hold the portrait, demonstrating through such a display of wealth their loyalty to their Queen, as, for example, ‘The Heneage jewel’ may do. This has four different faces, with the front cover, reverse, portrait and inside cover of the portrait, and two frames (back and front). The gold bust of Elizabeth is protected under a glass of rock crystal and bordered with an inscription identifying her as ‘…Queen of England, France and Ireland’; the frame around it is enamelled forget-me-not blue and decorated with little pierced gold Mannerist cartouches crested with green leaves, between the nine impressive diamonds and rubies which are clasped across this frame – the diamonds being crested with hooked scrolls enamelled in red and white. The reverse of this frame holds an enamelled painting on gold of an ark – apprarently the ark of the English Church, within an inscribed border – and is itself coloured white, with the backs of the clasps (revealed to be shaped like lilies) which hold the precious stones picked out in red, green and blue.

Nicholas Hilliard, ‘The Heneage jewel’, further faces

This frame also holds the miniature portrait of Elizabeth beneath the ark, the pierced white surround appearing to extend her great lace ruff, and the coloured enamels echoing the jewels she wears. The underside of the ark is painted with a red rose, and surrounded by a further inscription regretting that Elizabeth’s virtue and beauty should not be eternal.

Today, only seventeen original jewelled cases survive, out of around 180 portrait miniatures produced by Hilliard, and thought to be authentic or ascribed to him. Around the same number should be considered as surviving for this period in general; that is to say, fewer than 10% of the original cases survive from the pieces which have come down to us. Following on from this figure, as it is estimated that only 10% remain out of the total number of portrait miniatures which were executed, that means that we only possess 1% of the number of of jewelled mounts made for portrait miniatures in this period. Most of them must have been melted down or altered, in order to use the jewels and gold as a resource in hard times. The surviving ones are therefore even more precious, as they are rare witnesses to a European court culture which is only now beginning to reveal its deepest secrets.

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), ‘The Lyte Jewel’, Portrait of James VI of Scotland & I of England, 1610-11, watercolour on vellum, enamel, gold, diamonds; miniature, lid closed & reverse. © Trustees of the British Museum

***********************************

Bibliography

Princely Magnificence: Court Jewels of the Renaissance, 1500-1630, exhibition catalogue, London, Debrett’s Peerage Limited & Victoria & Albert Museum, 1980

Artists of the Tudor Court : The Portrait Miniature Rediscovered, exhibition catalogue, Jim Murrell and Roy Strong (ed.), London, Victoria & Albert Museum, 1983

Erna Auerbach, Nicholas Hilliard, Londres, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1961

Michèle Bimbenet-Privat, Les orfèvres parisiens de la Renaissance 1506-1620, Paris, Commission des travaux historiques de la ville de Paris, 1992

Katherine Coombs, The Portrait Miniature in England, Londres, V&A Publications, 1998

Marianne Grivel, Guy-Michel Leproux & Audrey Nassieu Maupas, Baptiste Pellerin et l’art parisien de la Renaissance, Paris, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2014

Diana Scarisbrick, Bijoux à portrait. Camées, médailles et miniatures des Médicis aux Romanov, Londres, Thames & Hudson, 2011

Biography

Céline Cachaud is an independent consultant in art, specializing in 16th and 17th century portrait miniatures in Paris. She graduated from the École du Louvre in 2015 and the École Pratique des Hautes Études in 2017. Her master’s thesis deals with Nicholas Hilliard’s trip to France (1576-1579) and its consequences both for his art, and for the renewal in the production of portrait miniatures in France at the end of the 16th century. She is preparing a PhD thesis project on this particular subject, and on the theory of painting miniatures in Paris and London during the Renaissance. She has published articles in, for example, Connaissance des Arts; she also founded and runs the online resources, Hillyarde & Co, and Un Art Anglais ? for the promotion of the study of British Art in France.

***********************************

Addendum

Unknown artist, ‘The Blairs Reliquary’, Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots, watercolour on vellum, 1 3/16 ins diam. (3 cm.), 8 x 6 cm. overall, framed 1610-22, & reverse, Blairs Museum Trust. T 1068 BLRBM

A foil to the miniature of James VI and I by Hilliard and its opulent setting in ‘The Lytre Jewel’, is formed by ‘The Blairs Reliquary’ with its miniature portrait of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots. This miniature was painted in 1586, but the reliquary frame, which comprises the gold setting and the case on the reverse, is almost co-aeval with ‘The Lyte Jewel’, dating between 1610 and 1622. It has Mary’s monogram on the back: ‘M.R’ for ‘Maria Regina’, and ‘A’ for ‘Albany’ (her husband Lord Darnley having been created Duke of Albany) [7]. This is combined with the names of eighteen other Catholic saints, including Carlo Borromeo, Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier [8], which by association also present Mary as a martyred saint.

Both sides of the pendant are decorated with low relief enamelled foliate ornament, with centred sprays on the back and a scrolling garland on the front incorporating fruits and flowers. This is in the spirit of Renaissance garland frames, most notably in those used by the Della Robbia family as three-dimensional borders for their relief tondi. The flowers and fruit in these garlands are symbolic, and this seems to be true of the decoration of ‘The Blairs Reliquary’; there are daisies, signifying humility or meekness, pears for the love of Christ, lemons for fidelity and pomegranates for resurrection. All these could easily have been applied to Mary as a Catholic martyr after her death.

‘The Fettercairn Jewel’, 1560-80, gold, enamel & almandine garnet, 5cm., cover, interior & reverse, National Museums Scotland

‘The Fettercairn Jewel’ is, as it were, all frame and no content. It is a gold pendant locket which dates from about 1560-80, and almost certainly once contained a miniature portrait – but this was apparently deliberately removed from it at some point. It was acquired in March this year (2017) by National Museums Scotland from the Forbes family of Fettercairn House, Aberdeenshire, with the help of the Art Fund. The front is set with a large, probably garnet, panel between spandrels enamelled in black, white and green with fine arabesques, and the back shows the figure of Hermes, messenger of the gods and guide to the underworld, a dog, a parrot, birds and butterflies, all enamelled in strong clear colours, like stained glass. Like ‘The Blairs Reliquary’, these motifs may be symbolic, possibly indicating that the original portrait could have been a posthumous image. As with so many other pendants, a pearl may have hung from the lower ring [9].

The wearing of miniature portraits as pendants or brooches in the 16th century, explaining and revealing the sheer opulence of many of their settings, is witnessed by their appearance in full-scale portraits – and even in the miniatures themselves – on both male and female sitters.

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (c.1561/62-1636; circle of), Portrait of Lady Denman/Denham/ Dormer, c.1595-1605, & detail, Christie’s, October 2015

This portrait, possibly of Lady Denman, or, again, of Dorothy Dormer, depicts a woman close to the heart of the Elizabethan court, who wears emblems and colours associated with the queen, and whose cameo portrait, hanging from her bodice, may be that of Elizabeth herself. The cameo is framed in gold with an inner scalloped pattern, probably in white enamel, and has a single pearl drop below. Portraits like this seem often to be worn asymmetrically, as here, on the side of the dress, or fastened to a sleeve , or worn as a pendant but pinned to the side.

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (c.1561/62-1635), A woman called Elizabeth Knightley, 1591, o/panel, 36.75 x 28.25 ins (93.3 x 71.8 cm.), & detail, Yale Center for British Art

Lady Knightley (?) also wears hers asymmetrically, on her sleeve, and again it has a single pearl drop; but it is very differently decorated on the cover – richly enamelled in what appears to be low-relief, with precious or semi-precious gems embedded in a classical scene. This is difficulat to interpret, but includes a columned building or entrance, with two lovers before a green tent (possibly Psyche discovering Eros?), and two seated goddesses (Athena and Aphrodite?) in the foreground. If these are indeed the actors in this scene, then it is probably a love token: perhaps a betrothal gift. It is finished with Mannerist masks at the bottom.

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (c.1561/62-1635), Sir Francis Drake, 1591, o/c, 116.8 x 91.4 cm., National Maritime Museum & detail of ‘The Drake Jewel’

Sir Francis Drake wears ‘The Drake Jewel’ centrally, hanging from his belt, where it shines dramatically against his black costume, the rubies picking up the scarlet in the mantling around his recently-granted coat of arms at the top left, the tropics outlined on the globe before him, and the warm tones in his face. The jewel seems to have acquired more pearls hanging from the bottom ring than the single large teardrop pearl shown in the painting, but its richness is evident, and Drake may have been depicted in a sable suit specifically to display the lavish gift of his queen.

Nicholas Hilliard (1547-1619), Portrait of a man against a background of flames, c.1600, watercolour on vellum on card, 6.9 x 5.4 cm., © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Drake’s is a full-scale public portrait, advertizing his status and his relationship with Elizabeth. At the other extreme is a very private miniature by Hilliard – the portrait of a man in dishabille against a background of flames. He wears a miniature pendant himself, but turns the cover outwards and the painting inward to his heart, in an intimate gesture towards the beloved who is the focus of the painting. Presumably the portrait was a gift to her, to let her know that he burnt with desire for her? – although there seems to be no sign that it had a cover itself, so she could not have worn it in public; perhaps the lover himself wore it, to try to move her? The face of the pendant depicted in the miniature looks as though it is decorated with an eagle: perhaps the eagle who continually tears out Prometheus’s liver, as a symbol of the torture the beloved is inflicting. Unusually the pendant is not finished with a pearl, but with a stone which echoes the grey tones of the cover, within its garland of gold leaves.

Hilliard died in 1619, two years after his pupil, Isaac Oliver (c.1565-1617), who had also worked for the English court. Any legacy of Hilliard’s skill and style therefore passed indirectly to Oliver’s son, Peter Oliver (1594-1648), another court portraitist who carried on the fashion for the miniature pendant.

Henri Toutin (1614 – post 1683) after Peter Oliver (1594-1648), Venetia Stanley, Lady Digby, 1637, enamel on gold, 4 15/16 x 3 1/4 ins; frame by Gilles Légaré (c.1610-post1685), Walters Art Museum

The portrait above and and its extraordinary frame, commissioned by Sir Kenelm Digby, is, in a way, related to Hilliard’s burning man – an outpouring of love, but here as a memorial of Digby’s dead wife, Venetia Stanley.

Peter Oliver (1594-1648) after Van Dyck, Sir Kenelm & Lady Digby & children in an ebony triptych (17th-18th century), containing miniatures of Venetia, Lady Digby and Lady Arabella Stuart set inside the doors, & detail; NationalMuseum, Stockholm

It is based on a miniature by Peter Oliver, and was executed by one of the earliest portraitists in enamel, Henri Toutin [10], in Paris, where Digby himself was from 1635-36. The original painting by Peter Oliver was probably the one above, on the right, slightly updated.

The frame of the version by Toutin was produced by the goldsmith Gilles Légaré, and represents a virtuoso development of the enamelled miniature frame from the decorative border of a jewel to something much more akin to a carved wooden Mannerist picture frame.

Gilles Légaré (1610-85), title plate, Livres des ouvrages d’orfevrerie, engraving, 1663, published 1680-1700, © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Légaré was Louis XIV’s goldsmith and jeweller, noted for the extraordinary skill he displayed in creating such frames. Peter Fuhring reports Pierre-Jean Mariette mentioning this talent; he owned

‘…a miniature portrait of the beautiful Countess d’Olonne painted by Jean Petitot after Pierre I Mignard. It was surrounded by an oval garland of flowers in relief, painted in enamel by Gillas Légaré who… surpassed all those who practised the same métier…The abbé Fontenay echoed this appreciation, writing that Légaré’s ornamental frames, painted in enamel, could pass as true chefs-d’oeuvre, not only for the delicacy of the craftsmanship but also for the brilliancy of the well-applied colours. [11]‘

The frame of Lady Digby’s portrait is a remarkable achievement, considering its size, and that Légaré was only twenty-seven when he made it. The miniature itself is held in a very slender border of dark blue banded with gold; this is supported by pierced scrolls in blue and gold entwined with green palm leaves, on which stand two elegantly curving and elongated figures. They could be Adam and Eve, but might also be Apollo and Aphrodite, or Eros and Psyche, given Venetia Digby’s legendary beauty, and that this is a memorial of her. The frame has the arms of Sir Kenelm and Lady Digby in a cartouche at the crest, and is surmounted by a scallop shell – perhaps again a reference to Aphrodite.

Henri Toutin after Peter Oliver, & Gilles Légaré, Venetia Stanley, Lady Digby, 1637

Francesco Primaticcio (1504-70), Scenes from the history of Alexander, with supporting figures in stucco, 1541-44, L’escalier du roi, detail, Château de Fontainebleau

Carved figural frame, oak, originally parcel-gilt & polychromed, 1550-80, 15.8 x 11 cm., overall 48.5 x 28.4 cm., © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

The figures on the frame are very much in the spirit and style of Northern Mannerism, and may be influenced by the sculptures of Fontainebleau, which are elongated and S-curved, and which also support picture frames. As the court jeweller, Légaré would have had access to the palaces, and would probably also have seen prints of the Fontainebleau decorations. The oak frame in the collection of the V & A shows the same type of Northern sculpture applied to a wooden picture or looking-glass frame, with the figures of Adam and Eve on either side, supported by pierced and scrolling Mannerist cartouches.

Légaré’s frame for the portrait of Venetia Digby is a miracle of the reinterpretation of such motifs, and of accommodating them to the scale of his work. It is a high point in the evolution of the miniature frame.

***********************************

Henry Bone: framing enamel paintings > here

***********************************

[1] Nicholas Hilliard, The Arte of Limning, R.K.R. Thornton & T.G.S. Cain (ed.), Manchester, Carcanet Press, 1992, p. 42

[2] Letters patent are documents recording, for instance, a grant made by the monarch to the person invoked, and which are not a private communication but a public record of the grant.

[3] What appears to be a drop of dew at the centre of the flower is an ivory plug, covering a hole where the ivory was attached to the lathe. Information from Alan Derbyshire, head of Paper, Books & Paintings Conservation, V & A.

[4] See Robert Knecht, Hero or tyrant? Henri III, King of France, 1574-89, 2016, ch. 2

[5] The cameo is carved with two profiles, a white queen and an African emperor, representing the alliance Drake made with African slaves in Panama against Spanish America

[6] See Janet Byrne, Renaissance ornament prints and drawings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981

[7] William Tudor-Jones, Finger-ring lore: historical, legendary, anecdotal, 2014

[8] Helen Smailes & Duncan Thomson, The Queen’s image: A celebration of Mary, Queen of Scots, exh. cat., Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1987, p. 38. Information from Anne Dulau Beveridge, Curator of British & French Art, The Hunterian, Glasgow.

[9] The style of enamelling on the reverse of ‘The Fettercairn Jewel’ has been related to the enamelled scenes and motifs of ‘The Darnley Jewel‘, a pendant which is not a frame, as it was not made to contain a painting (although bits of it open to disclose emblems and inscriptions).

[10] See Toutin’s portrait of Louis XIV as a boy in the Royal Collection.

[11] Peter Fuhring et al., eds, A kingdom of images: French prints in the age of Louis XIV, 1660-1715, Getty Publications, 2015, p. 135

Nice work.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike