Stefano Bardini: dealer, restorer and collector of frames

by The Frame Blog

Alison Clarke considers the collection, practice and legacy of the 19th century dealer and connoisseur, in respect of his picture frames

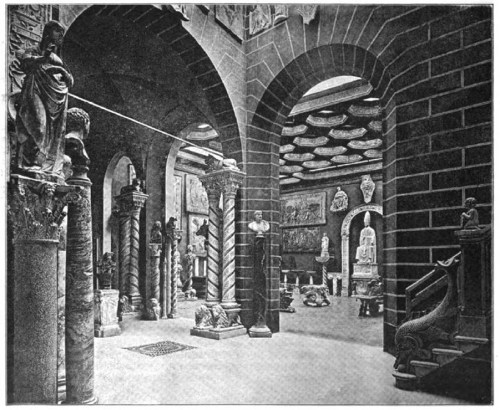

The Florentine art dealer Stefano Bardini (1836-1922) was, like so many of his contemporaries, a jack-of-all-trades. However, his restoration work—which occasionally strayed into the field of outright forgery—is particularly intriguing because it played such a key role in his self-promotion and the display of his wares. His Renaissance-style palazzo on Via dei Renai, Florence, was both a family home and a gallery open for visits by potential customers. The building’s interiors were especially admired by contemporary British visitors: journalist and art critic Thomas Humphry Ward wrote in the Art Journal in 1893 that Bardini’s ‘truly magnificent’

‘…palace—the word is strictly appropriate—is truly one of the sights of Florence […] filled with choice relics of the works done by the sculptors, the bronze-founders, the wood carvers, and the glass-painters of the Renaissance, together with fine specimens of Italian tapestry and Persian carpet weaving.’ [1]

The photographs illustrating Ward’s article reveal the crowded, decorative and heavily aesthetic slant to Bardini’s interior design approach.

‘Bardini’s at Florence’, The Art Journal, 1893

In particular, his interiors were intended to give his clients an idea of how paintings or sculptures could be placed in their own homes. As a result, he displayed objects in groups, with a strong nod to pattern and symmetry which often overrode their historic usage or intention. However, Bardini was not just thinking commercially: he also had one eye on posterity and his long-term reputation. Far from being particularly historic, his palazzo had in fact been purpose-built in 1880 to hold his collection; on his death in 1922, the building was then left to the city and now operates as the Museo Bardini. While the museum was rearranged in the 1920s to suit contemporary tastes, in 2009 it reopened after ten years’ restoration work intended to bring it back into line with Bardini’s original vision. This was, after all, no casual display but a well thought-out strategy to impress visitors with Bardini’s taste, culture and connoisseurship — both during his commercial career, and after his death.

The modern redisplay of the ‘Sala del Crocifisso’ (Crucifix Room) at the Museo Bardini, 2017. Photo: Alison Clarke

In particular, frames were key to Bardini’s display practice. Reflecting his attitude towards historic objects in general, he was not above making substantial alterations to frames in order to make them more appealing to the eye of a nineteenth-century buyer: cutting and reassembling, filling and gilding.

Tuscan door frame, with details of têtes espagnolettes on inner edge & angel on centre frieze

Fragments of frames were incorporated into the door frames, ceiling and cornices of his palazzo. Equally, pictures themselves would be cut down or reshaped to suit existing frames.

Donatello (circa 1386-1466; after), Madonna and Child, gilt & painted stucco relief, Italian, in later frame, overall 46 ¾ ins (118.7 cm.), collection of Stefano Bardini until 1913, Sotheby’s New York, 26 January 2012, Lot 328

Bardini had a large collection of frames and these would be brought into play whenever a painting was acquired unframed, or in a frame which he felt to be inappropriate to the picture. An on-site workshop allowed restoration work to be carried out under the dealer’s watchful eye, or, indeed, by his own hand. [2]

Stefano Bardini’s gallery, black-&-white photo from c.1900

He seems to have been particularly keen on the aesthetic of the stucco or terracotta relief of the Madonna and Child in a tabernacle frame with a pointed or segmental pediment. This preference is clear in an archive photograph dating from around 1900, which shows a dense hang of such works on a single wall of his gallery.

Bernardo Daddi (fl. 1312-20 – d.1348; attrib.), Crucifixion, inv. no. 771, & detail, Museo Bardini

Frames also seem to have been built from scratch as necessary. For example, detailed technical analysis has revealed that the large Crucifixion, which is one of the most striking works at the Museo Bardini, was constructed from a number of separate panels by both Bernardo Daddi and, potentially, an artist from the school of Orcagna. Instead of re-using existing frames from Bardini’s collection, however, in this case the polylobed frame appears to have been built especially for the reconstructed work (with the possible exception of the predella).

Bernardo Daddi, Crucifixion, detail of frame on predella panel

The simple lines of the frame and relative restraint with regard to ornament mark out the Crucifixion to modern eyes as a hybrid object: partly created in the late medieval period, brought together with alterations in the nineteenth or early twentieth century, and now exhibited in a twenty-first-century reconstruction of Bardini’s own display.

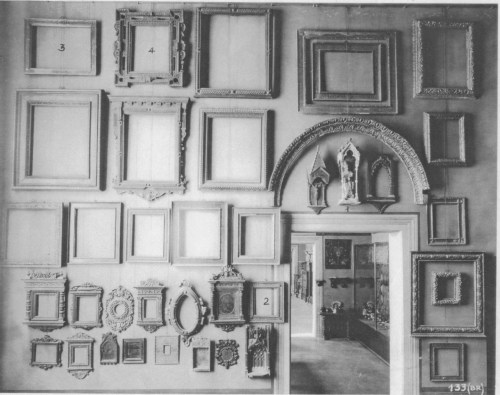

Stefano Bardini’s gallery, black-&-white photo from c.1900

Not only did Bardini alter and construct frames for the works that he acquired, but he also appears to have been an early appreciator and collector of frames as works of art in their own right. As early as 1900, archive photographs of the interior of his palazzo reveal that he dedicated an entire wall to the hanging of empty frames, grouping these by size and creating both horizontal and vertical lines to lead the viewer’s eye. While Bardini must have had enough paintings or reliefs to fill this wall if he had so desired, instead he deliberately chose to focus attention on the workmanship and skill which had gone into the creation of these historic frames [3].

While already arresting in the black-&-white image above, the impact of this display tactic is felt even more strongly in the modern redisplay at the Museo Bardini.

First-floor room at the Museo Bardini, 2017. Photo: Alison Clarke

Here, the gilt and wood of the frames stand out strongly against the characteristic ‘Bardini blue’ that inspired Isabella Stewart Gardner in Boston to adopt a similar colour for the display of her own, magnificent collection. As with Bardini’s original displays, in this modern hang more attention has been paid to the aesthetic impact of combinations of shape and line than to any strict delineation by style or period. The result is perhaps less to inform the visitor about the historic development of frames than it is to impress with the variety and craftsmanship of an often overlooked art form: thereby accurately reflecting Bardini’s own complicated attitude towards historic objects in general and frames in particular.

Domenico Rosselli (c.1439-98), Madonna & Child, marble relief, c.1480, 23 1/4 x 17 1/4 ins (59 x 43.8 cm.), collection of Stefano Bardini until 1918, Sotheby’s New York, 27 January 2011, Lot 417

Antonio (c.1432-98) & Piero del Pollaiuolo (c.1441-before1496), St Michael doing battle with the dragon, before 1465-70, with detail of the superb but worn sgraffito decoration of the frame, Museo Bardini

****************************************

Sources and further reading:

Lynn Catterson, ‘Introduction’, in Dealing Art on Both Sides of the Atlantic, 1860-1940, ed. Lynn Catterson (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp. 1-36.

Lynn Catterson, ‘Stefano Bardini & the Taxonomic Branding of Marketplace Style. From the Gallery of a Dealer to the Institutional Canon’, in Images of the Art Museum, ed. Melania Savino and Eva-Maria Troelenberg (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2017), pp. 41-64.

Lucia Mannini (ed.), Le stanze dei tesori: Collezionisti e antiquari a Firenze tra Otttocento e Novecento [exhibition catalogue] (Florence: Polistampa, 2011), pp. 126-137. In both Italian and English.

Anita Fiderer Moskowitz, Stefano Bardini ‘Principe Degli Antiquari’: Prolegomenon to a Biography (Florence: Centro Di, 2015).

Thomas Humphry Ward, ‘Bardini’s at Florence’, The Art Journal, 1893, pp. 10-15.

****************************************

Alison Clarke is a PhD candidate at the University of Liverpool and the National Gallery, London. Some of the research for this blog post was presented at the NAVSA/AVSA conference in Florence in May 2017. It was made possible by the financial support of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the British Association for Victorian Studies (BAVS).

****************************************

[1] ‘Bardini’s at Florence’, The Art Journal, 1893, pp. 10-15.

[2] The present-day framemaker at the Museo Bardini is Tommasso Nesi, the grandson of one of Bardini’s own craftsmen.

[3] It is interesting to note that Wilhelm von Bode (1845-1929), one of the earliest art historians to write on the importance of collecting, conserving and employing antique frames in museum collections, was a client of Bardini.

16th century Venetian restello or looking-glass frame, with hippocamps in the side brackets

Assemblage of Gothic portal and statuary