The exhibition Regards sur les Cadres, and the frame collection of the Louvre

by The Frame Blog

Louise Delbarre visits the exhibition of picture frames at the Musée du Louvre (27 June to 5 November 2018), and talks to its curator, Dr Charlotte Chastel-Rousseau.

In the storerooms of the Louvre there is hidden treasure. Its existence and size are generally unknown to visitors to the Museum: no less than 3,000 empty frames, which include some really exceptional pieces, acquired from earlier reframings, from purchases by the Louvre itself, or as gifts from art dealers and collectors. Together with the frames actually on the paintings, it constitutes a unique collection of around 9,000 frames reflecting the Museum’s long history, from the royal collections of French monarchs to the Louvre we know today.

Regards sur les cadres is part of a series of summer exhibitions presenting the research carried out in the curatorial departments of the Louvre. The frame collection, which is kept by the Department of Paintings, is currently being inventoried: first the frames in storage, to prepare for their move in 2020 to the Louvre’s new Conservation and Storage Centre, which is under construction in Liévin, in the North of France; and then the frames surrounding the paintings in the galleries. This inventory, under the direction of Dr Charlotte Chastel-Rousseau, the recently-appointed curator responsible for the frame collection, Cristina Arlian and Elsa Marcot, is the first stage in a renewed interest in this unsung part of the painting collections in the Louvre. If there has always been a concern for their important rôle in the display of paintings, the frames are now also being acknowledged as works of art in their own right.

“[Top right] Flemish c.1650-1680

Reverse frame: stained wood, tortoiseshell veneer, giltwood acanthus leaf corners

[Top left] Flemish c.1640-1660

Reverse frame: wood, veneered in tortoiseshell & palisander; previous frame of Memling, L’Ange tenant un rameau d’olivier

[Below] Netherlands or Italy? C.1650-1700

Reverse frame: stained wood, tortoiseshell veneer; previous frame of Lubin Baugin, Dessert de gaufrettes (see below)

We should salute this first exhibition in the Louvre devoted to the frame. Although it comes rather late, compared with other exhibitions in Britain and the US, it will bring others in its train, since the many topics raised in relation to the Louvre’s exceptional collection of frames are addressed in just three rooms: the intrinsic beauty of certain masterpieces, the complexity of their historical and aesthetic relationship to the paintings, and also their place within the museum. The number of these viewpoints introduces the prospect of future, more thematic exhibitions – and, as with the overture to an opera, we shall eagerly await what follows. This exhibition pricks the imagination and attention of all visitors, making them suddenly realize the importance of part of the work of art which they had hitherto ignored. This necessary, if belated, realization amongst the French will feed into, and feed on, similar work which has already begun in other countries.

A particularly stimulating new era is beginning, as Charlotte Chastel-Rousseau has many other projects in hand: a guide to the most beautiful frames in the galleries of the Louvre will soon be published, and the current inventory of the frames in storage will also result in a publication. The creation of a working group on French 18th century frames is also planned, as they belong to the golden age of French craftsmanship and are one of the highlights of the Louvre’s collection.

According to Dr Chastel-Rousseau, ‘two aspects of the frame are at stake: firstly, the preservation and conservation of the collection, and secondly, its presentation to the public. The first point, the transmission of the collection to the next generation, was put in hand under the direction of my predecessor Marie-Catherine Sahut, who was curator of the frame collection and of 18th century French paintings until 2012. She was a pioneer in the understanding of the historical and artistic values of frames. When the ‘Grand Louvre’ project was undertaken in the 1980s and new storage areas were constructed, she gathered all the empty frames together in one location, where they were organized by school (Italian, French, Spanish, Dutch and Flemish) and by style. This important work initiated a change of status for frames in France. Now that French museums are increasingly interested in frames for their own qualities, and for what they tell us about the history of taste and the history of display, it is time to give more visibility to the fascinating collection kept by the Louvre of around 9,000 items, which includes both the empty frames in store and the frames surrounding the paintings. The exhibition marks the beginning of a new approach to this unique collection’.

First room: empty frames from store

The first room of the exhibition is devoted to some of the most beautiful empty frames usually kept in store. A second room addresses the question of the harmony between picture and frame, and the third displays some very important framed paintings from the galleries of the Louvre where they usually hang. It gives a unique opportunity to appreciate the finesse, virtuosity and creativity of frames which generally go mostly unnoticed by the public, because they are surrounding masterpieces. The visitor can conclude the tour with a trail in the Museum through the rooms holding French paintings, where the most remarkable frames are highlighted with distinctive labels.

What follows here is a brief tour of the exhibition with Dr Chastel-Rousseau as the guide; she will explain the various topics addressed in different areas of the display, before answering some further questions about the management and history of the frame collection.

Charlotte Chastel-Rousseau: We asked ourselves if we were going to show only empty frames, or include framed paintings too. Displaying frames on their own is important, because it highlights their inherent historical and artistic values. The exhibition is a great opportunity to hang very interesting frames that are usually kept in store and have never been presented to the public. But the Department of Paintings is expected to show the Museum’s pictures; besides, considering the frames without raising the question of their relationship to the paintings would be misrepresenting them. We had to find a way to discuss the interplay between the two parts of the work of art.

Italian carved, water-gilded & painted cassetta, with outset corners holding roundels with sculptural male heads; centre clasps scrolled over the top edge, double leaf-tips; frieze with panels of elongated flowers, florets & centre reversed flowers; continuous spiral ribbon; stopped-channel fluting; astragal-&-double bead; (?)Bologna, c.1550-1600, 168 x 143 cm. overall, Edouard Grosvallet bequest (1987), frame n° OD 110, Musée du Louvre

C C-R: This first room reflects the diversity of the frames in storage: Italian, Northern European and French pieces are displayed together to introduce the visitor to their respective designs and the different techniques they employ. The most spectacular example is a 16th century Italian frame bequeathed in 1987 to the Louvre by the frame dealer Edouard Grosvallet, with a male head at each corner. It is thought to come from Emilia-Romagna, but there is no firm evidence as yet. I hope that one day we will find documents allowing us to identify by whom and for which painting it was created. Extensive research work still needs to be done on most of the frames at the Louvre, to find as much information as possible about their provenance and their history.

Second room: picture and frame

C C-R: The various solutions to framing a picture are the theme of the second room. It would have been visually striking to use reproductions of the same painting displayed in frames of different styles. However, the choice was made not to use reproductions but only original works: I strongly believe that the displays in museums should emphasize that paintings are not only images, and that they are valued for their very materiality. By focusing on the frames, we remind our public that paintings are objects in three dimensions with a long history. Therefore we needed to find another way to make people think about what makes a happy marriage between a picture and a frame.

Lubin Baugin (c.1612-63), Nature morte à l’échiquier, c.1630, o/panel; Louis XIII giltwood frame with torus of flower sprigs & reversed buds in a foliate chain on a cross hatched ground, with acanthus leaf corners; centred ribbon-&-stave with leaf corners at the sight edge; inlay to fit panel; Musée du Louvre

Lubin Baugin (c.1612-63), Le dessert de gaufrettes, c.1631, o/panel; 17th century Baroque bolection frame with acanthus leaf back edge; small centred ribbon-bound bay leaf garland; larger ditto at top edge; inlay to fit panel; Musée du Louvre

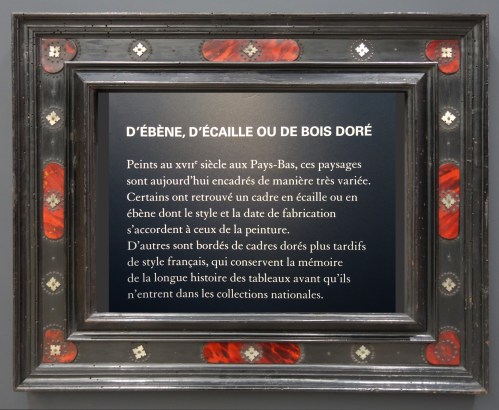

On the first wall of the room, different framing choices for French still life paintings by Chardin and Lubin Baugin are shown. On the opposite wall, Dutch landscapes from the 17th century appear in very different settings: two of them have been reframed in accordance with the style, period and school of the painting, one with a Dutch ebony frame, and the other in a frame veneered in tortoiseshell with ebony ripple mouldings. The other two have French 18th century giltwood frames, contrasting with the paintings, but nonetheless very interesting because specially made for them.

Johannes Lingelbach (attrib.; 1622-74), La Dînée des voyageurs, c.1650 (?), oil on copper, n° Inv. 1451, in French giltwood Louis XV ogee frame, c. 1720-40, with shaped contour, foliated back edge; foliate corners with palms & oval bosses and foliate & reversed flower centres; ogee with foliate strapwork; ribbed boss & fret in spandrels; chain moulding at sight edge; 62 x 74 cm. overall; Musée du Louvre

C C-R: This extraordinary frame bears on its back the same two wax seals as the ones on the reverse of the panel it encloses, pointing us towards the fascinating 18th century collection of Victor-Amédée de Savoie, Prince de Carignan. This is an exceptional frame with an incredibly luxuriant pattern: for instance the ‘batwing-like’ motifs [on the bosses in the spandrels]. It was made much later than the painting, most probably in the 1730s for the Prince de Carignan, and then purchased along with the painting by Louis XV in 1742. Shortly after the French Revolution it was put on public display in the Museum Central des Arts de la République, the ancestor of the Musée du Louvre, when it opened in 1793 [1]. Keeping this frame thus respects the history of the painting, and takes into account its life before it enteried the French national collection.

Third room: important frames and their paintings

John Martin, Pandemonium, c.1841, o/c, n° RF 2006-21, in its original British oil-gilded frame with ovolo chain at back edge; corner sculptural dragons; cartouche at crest supported by serpents; knot of serpents at base, acanthus ogee at sight edge; ornaments applied in compo; 162 x 223 cm. overall; Musée du Louvre

C C-R: The third and last room focuses on the highlights of the collection of frames which regularly hang in the galleries of the Louvre, with three diverse examples: first, frames from the royal collections; second, one of the most important frames in the collection, an artist’s frame by John Martin; and, third, the example of a recent reframing to show the public that this process is still going on in the Museum.

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), La pêche, c. 1585-88, o/c, n° Inv. 209, 136 x 255 cm., in French giltwood Louis XIV frame, c. 1665; with leaf bud back edge; scrolling corner & centre cartouches with shells & fishing motifs; ogee with foliate scrolling strapwork & floral rinceaux; centred spiral leaf-bound fasces at sight edge; plus details of top & bottom centre ornaments, Musée du Louvre

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), La pêche, c. 1585-88, o/c, n° Inv. 209, 136 x 255 cm., in French giltwood Louis XIV frame, c. 1665; with leaf bud back edge; scrolling corner & centre cartouches with shells & fishing motifs; ogee with foliate scrolling strapwork & floral rinceaux; centred spiral leaf-bound fasces at sight edge; plus details of top & bottom centre ornaments, Musée du Louvre

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), detail of the pendant, La chasse,c. 1585-88, with hunting motifs; Musée du Louvre

C C-R: Here is the first work from the former royal collections: a Louis XIV frame around a painting by Annibale Carracci from the late 16th century. There are two major disjunctions between the picture and its frame: of time, and of location. These disjunctions however belong to the painting’s history: when it was purchased by the administration of the Bâtiments du roi for Louis XIV, together with its pendant, La chasse (which represents a hunting scene and currently hangs in the Grande Galerie of the Museum), new frames were commissioned for both. The frame of La pêche is carved with motifs in keeping with the subject, a fishing scene – hoop nets, cornucopiae, and dolphins’ heads (La chasse has the heads of hounds either side of a boar’s head). Stylistically, it is an exceptionally beautiful and imaginative carved frame, and it is also characteristic of Louis XIV style with foliate scrolling strapwork, floral rinceaux, a sanded flat, and projecting centre and corner ornaments. For all these reasons, we could not think of displaying the painting in another frame – even in a contemporary Italian pattern. The same is true for Ludovico Carracci’s Madonna & Child, below.

Ludovico Carracci (c.1555-1619), La Vierge et l’Enfant, c.1616-19, o/c, n° Inv. 184, in French giltwood Régence frame, c. 1715-30; with C-scrolled cartouches with floral paterae; foliate scrolling strapwork & floral rinceaux on the convex top edge; spandrels with strapwork panels, shells & morphing dragons’ heads; strapwork acanthus & leaf-bud ogee to sight edge; 125 x 125 cm. overall, frame n° Aulanier 1122; Musée du Louvre. Photo of detail: courtesy Musée du Louvre

Eustache Le Sueur (1616-55), Mort de saint Bruno le 6 octobre 1101, 1645-48, o/c, n° Inv. 8045, 193 x 130 cm.; François-Charles Buteux (1724-97), giltwood Louis XVI frame, 1777-83; with cross-cut acanthus ogee; beading; acanthus & flower spandrels; cartouche at the crest with bay leaf garland & branches; rais-de-coeur at the sight edge; 243 x 159 cm. overall, frame n° Aulanier 1070; Musée du Louvre

C C-R: A series of paintings depicting the life of St Bruno was commissioned from Eustache Le Sueur in 1645 for the Carthusian monastery in Paris. More than a century later, in 1776, the Carthusians offered them to Louis XVI, at the request of the Comte d’Angiviller, Director of the Bâtiments du roi.

Part of the St Bruno series hanging in the Musée du Louvre in their frames by François-Charles Buteux

When the paintings arrived in the royal collection, new frames were commissioned for the series, with the intention of displaying it in a projected museum; and the document commissioning twenty-two gilded oak frames from the carver, François-Charles Buteux, has been preserved. However, the series of St Bruno paintings has not always been displayed in the Buteux frames: in the 1950s, part of the series was reframed in dark wood, which was thought to be more appropriate to the severity and austerity of the Carthusian order. In the 1990s the decision was taken to reunite the paintings with their Buteux frames.

Mathieu Le Nain (c.1607-77), Le Reniement de saint Pierre, c. 1648, o/c, n° R.F. 2008-56, 95 x 122 cm., in French giltwood Louis XII-XIV frame, c. 1660-80; with acanthus back edge; convex top edge with C-scrolls, acanthus sprigs & leaf-buds, with acanthus corners on a cross-hatched ground; flower-enriched ovolo chain at the sight edge; Musée du Louvre

Italian giltwood leaf frame with acanthus and scrolls, Tuscany (?), 1650-1700, acquired with Mathieu Le Nain, Le Reniement de saint Pierre, in 2008, Musée du Louvre

C C-R: This painting by Mathieu Le Nain is one of the Louvre’s major recent acquisitions. It is displayed next to its former Italian leaf frame, which had been chosen by the art dealer before the sale. It is a very beautiful carved object, which to some degree does fit the Italian Caravaggesque inspiration of the painting. But it was not original to the picture, and the decision was taken to replace it with a French Louis XIII-XIV frame, which would help to convey the importance of the painting as a landmark in the history of French painting. It was also a way of harmonizing the whole work of art with the other 17th French century pictures by George de La Tour and the Le Nain brothers in the same room. The exuberant Italian frame would have created a disruption in the visual balance of the overall hang.

Louise Delbarre: Could you tell us more about the context of this renewed interest in frames?

Charlotte Chastel-Rousseau: The historical study of frames has developed considerably in European countries, and notably in Britain over the last 20 years, and this has undeniably been an inspiration to French museums. Besides, the Musée du Louvre currently employs six craftsmen specializing in carving and gilding, which is quite rare in France and very important in researching the Museum’s frame collection. The studio (directed by Elisabeth Grosjean) is in charge of restoring frames and other gilded objects in the museum, and of creating new frames. An important factor is also the need to move those frames which are currently in store in an area vulnerable to flooding by the Seine, to the Conservation and Storage Centre under construction in Liévin. Before moving around 3,000 empty frames we have to get to know them better: that is why we are undertaking a detailed inventory of the collection.

LD: The Second World War seems to have been a decisive moment for the Louvre’s frame collection?

C C-R: During both World Wars an evacuation of the artworks was organized. The paintings left without their frames, which stayed empty in the closed galleries of the Louvre.

Empty frames in the Louvre after WWII waiting to be reunited with their paintings; there are also photos of frames abandoned in the Grande Galerie. Photo: Roger Viollet

Germain Bazin was curator of the Department of Paintings during the Second World War. He had a personal interest in frames, and had already made decisions about reframing various works and making contact with potential donors. He entrusted a volunteer, Christiane Aulanier, with the task of producing an inventory of all the empty frames. This first inventory included around 2,000 frames. Bazin’s and Aulanier’s project was to acquire an extensive knowledge of the frame collection, in order to deal with – and possibly to improve – the framing of the paintings when they came back at the end of the war. They also purchased a lot of frames from dealers during that sensitive period; there is a quantity of archival material with which the history of these acquisitions can be traced. In his memoirs, Germain Bazin even stated that he used the savings on the heating budget to buy frames, as the museum was closed!

It was a period during which the frame collection was rediscovered, but also profoundly modified. In my current research work, I am trying to recover the history both of that time and of the whole collection, and to identify the successive frames for each painting. The war was a period of great interest for frames, and of great disruption too.

LD: What about the available archival material? The frames seem to be well-documented from the moment of acquisition, but what about their previous history?

C C-R: It is one of the major strands of the research we are conducting – trying to find the provenance of all the frames. The Aulanier inventory is a very important milestone in this process, but much work remains to be done. We have files and old photographs which have been kept by the Louvre, and there is a lot of material in the National Archives. Also, the backs of the frames have inscriptions, labels, stamps and all sorts of precious information, but it is not always easy to have access to them and to take photos.

Example of a frame (not in Musée de Louvre) stamped on reverse ‘E – L. INFROIT’: signifying the work of Etienne-Louis Infroit (1719/20-1795), maître at the Academie de Saint-Luc, 1759; also with partially-erased stamp at extreme right: ‘JME’ for ‘Jurande’ (or ‘Jurés’), ‘Maîtres’ (or Menuisiers’), & ‘Ébénistes’. Photo: with thanks to Bruno Hochart

Egbert van der Poel (1621-64), Une maison rustique, 1655, oil on panel, n° Inv. 1692, 60 x 83 cm.; Etienne-Louis Infroit, stamped giltwood Louis XVI frame, with piastre moulding on top edge; fluted scotia with acanthus leaf corners; punched spandrels with floral paterae; rais-de-coeur at sight edge; 80 x 104 cm. overall, Musée du Louvre

Stamp (estampille) of Etienne-Louis Infroit, from the Van der Poel frame (above, n° Inv. 1692); the stamp ‘JME’ is also visible on the right; Musée du Louvre

For instance, we recently discovered an Etienne-Louis Infroit stamp on one of our picture frames, which is displayed in the exhibition. Eventually, the aim is to gather as much information as possible on the history of each frame: there is still a lot of work to be done!

“Spanish (?) frame from the Dalbret Bequest (1942), c.1640, veneered in ebony, tortoiseshell & bone, with a ripple moulding added later at the sight edge, 76 x 62 cm. overall, frame n° Aulanier 1858, Musée du Louvre”

C C-R: There was another important moment during the Second World War: Ernest Dalbret, a frame dealer, who dies in 1941, bequeathed his stock to the French state. He had more than 2,000 empty frames, among which 900 pieces were kept by the Louvre as a reserve; these frames, chosen by Bazin and Aulanier, arrived at the Louvre in 1944. It was a major acquisition: a good number of the significant Italian or Flemish frames in the Louvre come from the Dalbret bequest. Since then, the curators have been using that stock progressively to reframe the paintings which need it.

“Florence (Italy) c.1600-1650. Reverse cassetta: painted & parcel gilt wood

Like several of the frames displayed in this room, this frame has on the back a label indicating that it was bequeathed by Ernest Dalbert (1861-1940), Parisian frame dealer. The Dalbert legacy allowed the Louvre to acquire more than 900 frames, of all nationalities, of which some, like this one, have a particular aesthetic interest.”

LD: There were a lot of changes in the framing of paintings in the Museum in the 1950s. What happens now? Do you continue to reframe your paintings?

C C-R: We are still seeking to improve the framing of some of the paintings, as illustrated in the picture by Le Nain displayed in the exhibition. The decision as to a change of frames is made in discussion between the Director of the Department of Paintings, the curator in charge of the individual painting, and the curator in charge of frames.

Jean-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), Pipes et vases à boire, dit aussi La Tabagie, c. 1737, o/c, n° MI 721, 32 x 42 cm.; in French giltwood Louis XVI frame, c. 1760-70, with astragal-&-triple bead; scrolling cartouche with ribbons at crest; beading; acanthus leaf-tips on hatched ground; 51 x 57 cm. overall, frame n° Aulanier 764, purchased in 1942, Musée du Louvre. Photo: Musée du Louvre

Jean-Siméon Chardin (1699-1779), La Table d’office, dit aussi Les Débris d’un déjeuner, 1763 (?), oil on panel, n° MI 1040, 38 x 46 cm.; in French giltwood Louis XV frame, c. 1740-60, with leaf tip back edge; swept S-scrolling rails; pierced scrolling foliate & rocaille corners with diapered ground & floral rinceaux; shell centres; acanthus leaf-tip & bud on hatched ground at sight edge; 54 x 62 cm. overall, acquired in 1993, Musée du Louvre

Many works by Chardin, for instance, have been reframed in genuine eighteen-century frames. Our dream is, of course, to find a frame in the same style and period as the painting, but this can be difficult, so it is not a systematic approach but more of a flexible guiding line. Also, size is an important constraint, because we do not cut frames to adapt them to paintings, as was – unfortunately – commonly done until a few decades ago.

“François-Charles Buteux ([actually 1722-1802]) Louis XVI frame, giltwood with pigment patina, 1777-83. In 1777 the Comte d’Angiviller (1730-1810), Director of the Bâtiments du roi for Louis XVI, commissioned François-Charles Buteux with the execution of twenty-two frames for the series of St Bruno paintings which had come from the Carthusian monastery. Each oak frame is decorated with different carved mouldings; here, cross-cut acanthus, beading, & husks at the sight edge. Originally the cartouche in the centre of the top rail would have held the name of the artist.”

[for Buteux’s dates, see the Dictionary of pastellists before 1800: Suppliers ]

There is also a particular trait of the Louvre, a characteristic it shares with a few other museums, such as the Hermitage or the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden: it holds beautiful frames which are not necessarily in harmony with the style and period of their paintings, but which do tell us something important about the history of the picture and also of the collection. We have a very large proportion of French frames at the Louvre – a lot of Empire and Restauration frames especially – which were ordered in the first decades of the foundation of the Museum. They have now become part of the ‘Louvre museography’, and we have to respect this heritage.

LD: Does the Louvre sometimes create appropriate new frames for pictures, as was recently done at Tate Britain for Constable’s Salisbury Cathedral from the meadows for instance [2]?

Adam Frans van der Meulen (1632-90), Le siège de Luxembourg, 1684-90, o/c, 87 x 157 ins (221 x 400 cm.), inv. 1507, in new giltwood frame, 2017, Musée du Louvre

C C-R: As we have so many beautiful frames in store, we always tend to look there first. We rarely create new frames: the team of the Atelier Encadrement Dorure concentrates on restorations and on making travel frames when they are needed. However, in 2017 it produced a giltwood frame for a very large canvas – a battle scene from Louis XIV’s reign, Le siège de Luxembourg by Adam Frans van der Meulen – which had been in store for a long time as it did not have a frame. The creation of such a large-scale setting is a real achievement, and I must say it is very satisfying to be able to display this painting at last in the recently refurbished galleries.

LD: What is the Louvre’s policy for regilding frames?

French Louis XIV frame with original water-gilding, c. 1660-90, 111 x 79 cm,. purchased in 2002, Musée du Louvre

C C-R: There is a taste for distressed gilding in France. It may be a misinterpretation, as we can assume the collectors of the ancien régime would not have accepted worn gilding on their frames. At the same time, the paintings were seen in a very different context: they were lit by candles and in harmony with the surrounding panelling, shimmering fabrics, porcelain… a whole setting that is hard to imagine in the Louvre today! In France in general, and at the Louvre in particular, there is a great respect for old gilding, even if it is very worn. For the interior of a private house, a perfect appearance may be preferred, whereas in a museum authentic historical gilding is valued. However, we do partly regild our frames. When we do so, we always think about the legibility of our operation. It is a delicate balance. We always ask ourselves how far we can accept a slightly damaged appearance, without distorting the perception of the painting.

LD: Does the Louvre still acquire frames?

C C-R: There has been a tradition of bequests and donations of frames ever since the 19th century. The collector Jules Strauss, for instance, bought a lot of frames for the Louvre in the 1920s and the 1930s. The Louvre has always purchased frames, and we want to continue this tradition. It raises the question of the acquisition procedure, as most of the frames in the Louvre are not registered on the museum’s legal inventory and do not have an accession number. As the status of frames is now changing, their legal registration is a very important issue that will be considered collectively in the coming years.

*****************************

With grateful thanks to Charlotte Chastel-Rousseau for her time, and to the Musée du Louvre for the images used in this article. Measures in the captions of the images indicate the overall (outer) dimensions of the frames, height x width. All photos by Louise Delbarre, unless otherwise stated; montages of texts within frames by The Frame Blog.

Louise Delbarre is a curator at the Institut National du Patrimoine, Paris. She graduated from Panthéon-Sorbonne University in 2014 and is currently researching a PhD thesis on the frames of the French Symbolists at Panthéon-Sorbonne University.

Regards sur les cadres is open from Wednesday to Sunday (the rooms containing 17th and 18th century French paintings are closed on Mondays), until 4 November 2018.

*****************************

Appendix featuring selected frames & their captions: The Frame Blog

The captions on the frame trail, from which these are taken, were written by Cristina Arlian.

“Ebony, tortoiseshell or giltwood.

Painted in the Netherlands in the 17th century, these landscapes are framed today in a very diverse fashion. Some of them have been reframed in a tortoiseshell or ebony frame in a style and period appropriate to the painting; others are framed in later French giltwood frames, which reflect the long history of these works before they entered the national collection.”

“German? 1650-1700. Carved, stained and polished frame.

A Northern style ebonized frame, which was the right size for the painting, was fortunately discovered in the frame store, and has been used to display this small landscape. The decoration of carved wave mouldings, which echoes the watery subject of the painting, suits it perfectly.

Peter Gysels (Anvers 1621-90), Pêcheurs près d’iune chaumière, oil on copper… frame bequeathed by Ernest Dalbret, 1944.”

“Flemish or Italian? 1650-1750. Carved and stained frame veneered in tortoiseshell.

The alternation of ebonized wood and tortoiseshell is characteristic of 17th century Northern frames. Visual and historic harmony can thus be found between painting and frame, even where these have been acquired separately.

Jan van der Heyden (Netherlands 1637-1712), Vue du Coudenberg…, o/panel, c.1670… frame bequeathed by Ernest Dalbret, 1944.”

“French 1650-1700. Louis XIV frame, giltwood with pigment patina. This frame, acquired in 1942 to frame Mignard’s Portrait of Madame de Maintenon, was adapted in 1949 for Georges de La Tour’s painting. This is a question of a remarriage, in the practice of which the Museum became very expert in the post-war years. The frame, which is executed with remarkable skill and elegance, is in Louis XIV style; it combines the linear with the very ornate.

Georges de La Tour (France 1593-1652), La Madeleine à la veilleuse, c. 1640-45, o/c.”

[The réparure, or recutting in the gesso, is refined and beautiful: minute cross-hatching over the entire ogee, diapering enriched with punching in the demi-centres, and double diapering in the corners & centres; the veins of leaves and shells have also been added. The frame has been cut on the vertical rail above the corner]

“French 1650-1700. Louis XIV frame, giltwood with pigment patina. This frame, acquired from a private collection, Place St Sulpice, Paris, is distinguished by the harmonious rendering of the ornament. It is decorated at the corners and centres with foliage, and on the reposes with engaved motifs.

Charles Le Brun (Paris 1619-90), Portrait on horseback of Pierre Séguier, Chancellor of France, c.1660, o/c.”

[The reposes, or mirror panels, show that this frame (often described as a panel frame) has also been cut to fit the painting, unfortunately through the engraved ornament]

“French, 1650-1700. Louis XIII frame, giltwood with pigment patina. Jules Strauss (1861-1943), an art lover and wise collector, was one of the prime movers in the policy of framing employed in the 1920s by the Museum. He gave around sixty frames to the Louvre, of which this is one. It is decorated opulently with sprays of large flowers at the centres and corners. It bears witness to the search to refine the presentation of the painting and elevate it to the rank of masterpiece.

Jean-Antoine Watteau (France 1684-1721), Pierrot, previously known as Gilles, c. 1718-19, o/c.”

[This is known as a ‘flower corner frame’ in English; the flowers are sculpted in high relief, and with great naturalism, in the case of the roses and paeonies]

“French, 1722-74. Louis XV frame, giltwood with pigment patina. The frames of Boucher’s Le moulin and Le pont are the result of the policy on framing developed by the Louvre in the 1930s. These frames are appropriate for the paintings in terms of both style and period. The contour is swept in S-scrolls, and its sinuous lines are enriched by a sanded frieze and by spiralling rinceaux.

François Boucher (Paris 1703-70), Le moulin and Le pont; both 1751, o/c.”

[The word ‘profile’ must be a misprint for ‘contour’, as the profile is not made of curves and counter-curves (i.e an ogee): it is hollow on the face and at the back; however, the contour has pronounced S-curves from corner to centre. A Rococo frame with scrolling rocailles at the corners which morph into the spiralling rinceaux]

“French, 1800-50. Empire frame; wood, plaster & patinated gilding. Empire frames appeared at the beginning of the 19th century; this sober, elegant style tended to homogenize the appearance of frames. From the outside inwards, the ornaments characteristic of the style can be seen: palmettes, acanthus leaves [? possibly a misprint for lotus or lily buds], bead-&-bobbin, a scrolling flower chain, and rais-de-coeur at the sight edge. The back edge of each rail shows that yellow ochre paint was employed, to save on gold leaf.

Marie-Guilhelmine Benoist (née de Laville-Leroulx, Paris 1768-1826), Portrait d’une femme noire, Salon 1800, o/c.”

[Note also the anthemia in the corners]

“French, 1830-50. Reverse frame, carved wood & patinated gilding.

During the 19th century frames became increasing eclectic, and many artists were directly involved in choosing their frames. The artist Ingres brought the greatest care of all to this choice. This sumptuous frame in NeoRenaissance style has inherited all the richness of the Italian repertoire of ornament: small birds play amongst the foliage.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (France 1780-1867), Louis-François Bertin (Bertin senior), 1832, o/c.”

[Ingres produced astonishing and technically challenging portraits, as well as very beautiful drawings; he also designed some of the most sophisticated frames in 19th century France. These are based on conventional structures, and use variations on traditional ornament, yet they look completely original and fresh; they also employ a witty symbolism which undercuts their academic cast, and is a long way from the run-of-the-mill Salon frame. M. Bertin founded the Journal des Débats in support of the July Monarchy, and the creatures which flutter and creep and play around the undulating vines on his frame seem to have a punning reference to his life. The dragonflies (libellule) may be lampoons (libelles); the doves (colombelles), mating and making homes (colombiers), bring in terms related to paper and printing; the lizards (lézards) could be lézardé – full of the crevices and chinks of political faultlines.]

*****************************

[1] Although the project of displaying objects from the royal collections in a museum began in the reign of Louis XVI, the Museum Central des Arts de la République, ancestor of the Louvre we know today, opened to the general public after the Revolution in 1793.

[2] John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the meadows, 1831, Tate Britain: the reframing process

[…] flowers. A late and splendidly sculptural example can be seen in action, so to speak, in the Musée du Louvre, where it has been used to frame Watteau’s Pierrot, previously known as Gilles, c. 1718-19; it […]

LikeLike

[…] Where Wilcox remembers just one book on framing when he started out in the 1970s, today there are dozens, and sites like The Frame Blog make conservators’ insight available to the masses. The marriage of time-honored craftsmanship and new technology has led to the development of environment-controlled frames that still honor the intent of the artist. And some museums, mainly in Europe, have curated exhibitions dedicated to the art of framing, including the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Louvre. […]

LikeLike