An introduction to frames with covers, shutters and curtains. Part 1: Covers and shutters on sacred works

by The Frame Blog

This seems to be, at first glance, an aspect of picture frame history which must necessarily be extremely small (not to say niche) and esoteric; however, there turn out to be so many varieties of curtains, fanning out from the intimate clothing of an altarpiece to vast painted works which furnish a whole pop-up chapel; covering secular paintings of every genre, and catalyzing their own section of trompe l’oeil trickery (not to mention the covers and shutters which provide frames with another pictorial field); that – even though relatively few examples of some of the objects themselves remain – it is difficult to know how widely to pursue the concentric ripples in such a large pool of drapery and dust jackets.

Early examples of shutters and covers

‘Framed’ painting of Narcissus, House of the Ara Maxima, 1st century AD, Pompeii

Covers for works of art go back a very long way: in fact, there are Roman frescos executed during the 1st century BC which show free-standing paintings (often of the gods, and therefore also sacred works) framed with doubly-folding shutters, which – like the wings of a triptych – enable them to stand upright, but which can also implicitly be closed to protect the paintings. None of these seem to be represented in a closed position, so it is impossible to see whether the trompe l’oeil shutters would, if real, have ornamented backs, but again this seems to be implicit in the design.

Framed wooden panel with painted portrait, 50-70 AD, tempera, 45.72 cm. h with frame, Roman; made in Egypt; British Museum

There is also the Egypto-Roman portrait of a woman in the British Museum (associated by its context in Hawara with funerary rites), the frame of which has inset grooves, indicating that it may originally have had a sliding shutter to protect it. Although any decorative finish of the frame has long worn away, it would probably – like antique sculpture – have been polychromed and even gilded, and any cover would presumably also have been finished with painted decoration. It may well have been painted years before the death of the sitter, and added to her burial as a mummy portrait would have been.

Evangelium longum, front cover with Christ in Majesty (32 x 15.5 cm.) and back cover with Assumption of the Virgin and St Gall & the bear (32 x 15.4 cm.), c. 894, both covers by Tuotilo, including the carved ivory panels and the gold and gemstone wrapped oak frames; Cod. Sang. 53, e-codices_csg-0053), Stiftsbibliothek, Abbey of St Gall, Switzerland

Then there are book covers, which act as protective containers for illuminated manuscripts, and are richly, symbolically, and sometimes pictorially, decorated themselves. These covers are also frequently arranged like framed paintings, with an outer ornamental border around a sacred work of art. The Evangelium longum, with its Carolingian ivories, is a particularly resplendent example of pieces of this kind which were connected with the court of Charlemagne and his successors [1], its covers forming a diptych with ornate golden frames decorated with repoussé foliate motifs and gemstone cabochons. Like later free-standing painted and carved diptychs, the ivory plaques inside these frames have been carved with two of the more important Christian images, of Christ in Majesty and the Assumption of the Virgin, turning the closed book itself into an item of contemplation and veneration.

Although the covers themselves were created first, they have been used to conceal, advertize, glorify and protect the manuscripts within, which were written by a monk named Sintram, revered for the steadiness and beauty of his script, and illuminated by him with gilded and silver-leaf capitals and graphic decoration. The text is a so-called Evangelistary, extracted from the Gospels and intended to be used in a Mass, although it is of such fine quality and the covers protecting it are so rich that it seems to have been a book for display rather than daily use.

Book of Gospels, front cover with Christ in Majesty, late Carolingian, c.1170-80, Cologne, silver-gilt, enamel, gemstones, 28 x 20 cm., holding an MS from St-Amand, c.860-80, Museum Schnütgen, Cologne

This is an example of a late Carolingian enamelled book cover with a very sculptural figure of Christ in Majesty and a clearly-defined frame of decorative and symbolic enamel plaques (it is not clear whether the intervening panels would have held some now lost ornament or relic). The angels at top and bottom represent the four corners of the earth, explaining in a single set of images the scope and direction of the gospels which they help to protect, and the reach of Christ’s power and compassion. The damage to the raised areas of the figure of Christ indicate that this was a book of gospels which was perhaps in much greater use than the Evangelium above, and was continually – like an altarpiece with shutters – opened and closed.

Ivory diptych with the Coronation of the Virgin & Last Judgement, ?Paris, c.1260-70, 5 x 5 1/8 x ¾ ins (12.7 x 13 x 1.9 cm.) when open, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Carved ivory panels gradually became detached from the book covers and furniture mounts of their early associations, moving into the mediaeval period as tiny portable sacred works in their own right: travelling altarpieces on a minute scale, which could be held in the hand and meditated upon at any time, even before such sophisticated versions of domestic and full-scale ecclesiastical altarpieces were being made. A diptych like this was its own cover and protection, shutting like a cigarette case to conceal and safeguard the holy images within, but able to support itself as a free-standing object when open.

12th century Byzantine triptych of Madonna and Child enthroned, with 15th century Italian cornice and pedestal, gilt bronze, open: 16 x 19 cm., closed: 16 x 11.9 cm., Victoria & Albert Museum

Small portable Byzantine altarpieces were also made of metalwork, here in the form of a triptych – book-like in their manner of opening, if not in their form, and anticipatory of the larger ecclesiastical altarpieces which would be produced. The example above has been given a later cornice and pedestal as it passed through Italy in the 15th century, conforming to the structures of wooden altarpieces at that time, although in its original form it is very similar to its ivory bretheren. At 16 cm. high it is still very portable, although without the cornice and base it would have been as slender as the diptych above. The shutters open to reveal the saints John Chrysostom and Gregory of Nazianzos, and close into a pair of decorated crosses, each with a rose for the Virgin at their centres. In this respect, they are perhaps similar to book covers. The imprese of their later Italian owners have been stamped at the foot of the crosses.

Pala d’oro (top), gold over wood, Byzantine enamel panels, gemstones: lower section, 1102-18, upper section, c.1204 onwards; with Romanesque and Gothic arched silver-gilt and gemstone overlay, 1343-45; 200 x 300 cm., Basilica San Marco Venice; and Paolo Veneziano (fl. 1300-c.1360) & sons, Pala Feriale (middle image), 1345, cover for the Pala d’oro of two painted wooden panels, each 59 x 325 cm.; and Maffeo da Verona, cover for the back of the Pala d’oro (bottom), 1614, panel, 135 x 247 cm.; both latter Museo di San Marco

In a similar way the gold, silverwork, enamel and gemstone covers of sacred books and portable images developed into full-size altarpieces: the largest surviving example being the Pala d’oro in St Mark’s Basilica, Venice, which accreted by several stages from the early 12th to the mid-14th centuries into the very large object it is today [2], acquiring, along the way, two different painted wooden covers to protect it. The Pala d’oro itself was only uncovered for important festivals, and otherwise the painted custodie stayed in place over both back and front. Laura Moretti notes, in her article on Sansovino’s architectural additions to St Mark’s, relative to the configuration of choral spaces, that,

‘…in the ceremony books the performance of Vespers by two choirs was a liturgical necessity for at least a third of the official feast days of the liturgical year of St Mark’s, and… two choirs were specifically required for all the occasions in which the Pala d’oro was opened: from Bonifacio’s Rituum Ecclesiaticorum Cerimoniale we learn that psalms for eight voices were sung on the days when it was displayed.’ [3]

The design of these services was based firmly in past custom, and music, voices and gilded retable were associated in a trio hallowed by tradition. The covers of the altarpiece were therefore more than just decorated dust jackets, as it were, but – when in use – symbols that ceremony had been laid by until the next sacred occasion when they would be removed. The paintings which hid the enamelled images of Christ Pantocrator, saints, prophets, angels, and scenes from the life of St Mark on their golden ground, with all the inset gems and pearls, were altarpieces in their own right, with their own images of Christ, the Madonna and saints. They were only less old, less steeped in tradition, further away from Byzantium and further from the scenes they showed: hence perhaps the reason that the earlier panels by Veneziano were not displaced by the more up-to-date paintings of the 17th century. This latter cover on the reverse of the Pala d’oro dates originally from the 15th century, when it was painted by Francesco Franceschi; it was overpainted by Maffeo da Verona in 1614 [4].

Altarpiece shutters in Italy

There must have been some encasing wooden framework around the Pala d’oro to allow the painted panels to be slid in and out, both in front of it and behind, but an easier method of covering images when the liturgy required it was to imitate the opening and closing of the earlier book covers and small ivory diptychs, and to use hinged shutters. Early examples of altarpieces designed as dossals – i.e. created to stand on the back of the altar (sometimes matched by a painted frontal on the façade of the altar itself) – can be dated back to the 12th century [5]; the earliest (or, at least, one of the earliest surviving) shuttered altarpieces of painted wood was produced in the second half of the 13th century.

Margarito d’Arezzo (fl. c.1250-90) & Ristoro d’Arezzo, Madonna and Child with scenes from the life of the Virgin (90 x 123 cm.), plus the now detached shutters (each 90 x 66 cm.), Santa Maria delle Vertighe, Monte San Savino. B-&-w photo of the shutters: Fondazione Federico Zeri

This is the triptych by Margarito and Ristoro d’Arezzo which remains in its 11th century native church in Monte San Savino, between Siena and Arezzo. The main panel with the Madonna by Margarito d’Arezzo has been mounted, with its painted shutters by Ristoro (now detached), as a long flat image in a modern wooden and parcel-gilt glazed case. Like most early dossals it has a horizontal format, making it over 2.5 metres wide with the shutters open, which would have produced a spectacular expansion from their closed state; this difference in size indicates the dramatic element in the liturgy, intended to reveal the ineffable through a visual coup de théâtre to the congregation when they entered the church, or when the shutters were opened before them. Of course, it is often impossible to show very old and fragile works of art otherwise than in purpose built boxes and glazed frames, but this preserving of them in a static aspic takes away the aspect of revelation through movement and unclosing which would have been made explicit during particular feast days in the Church.

Duccio (fl.1278- d. pre-1319), Crucifixion with SS Nicholas & Gregory, 1311-18, closed: 24 ins high (61 cm.), open: 24 x 15 1/2 ins (61 x 39.4 cm.), MFA Boston

Revelation of a different, more intimate and contemplative kind could occur through the medium of the domestic altarpiece. Unlike the tiny, folding, carved ivory panels which could be resorted to almost anywhere, like a prayerbook, these were for private chambers and might have stayed open for longer periods than church retables. They could also be closed functionally (as it were) when their owners took them travelling, when they would be carried in some sort of padded case. The outer shutters of this particular example are decorated rather like the tooled leather binding of a book, or the porphyry doors of a reliquary, and only the little gilded tympanum with Christ in a mandorla shows what is within. This is the grace note – a revelation of heavenly optimism – whilst inside is the illustration of Christ’s sacrifice; and the structure of the altarpiece, like a small chapel or church, opens its doors in a personal vision of His crucifixion, whilst the worshipper’s name or place saints look on from the doors (or the aisles of the chapel).

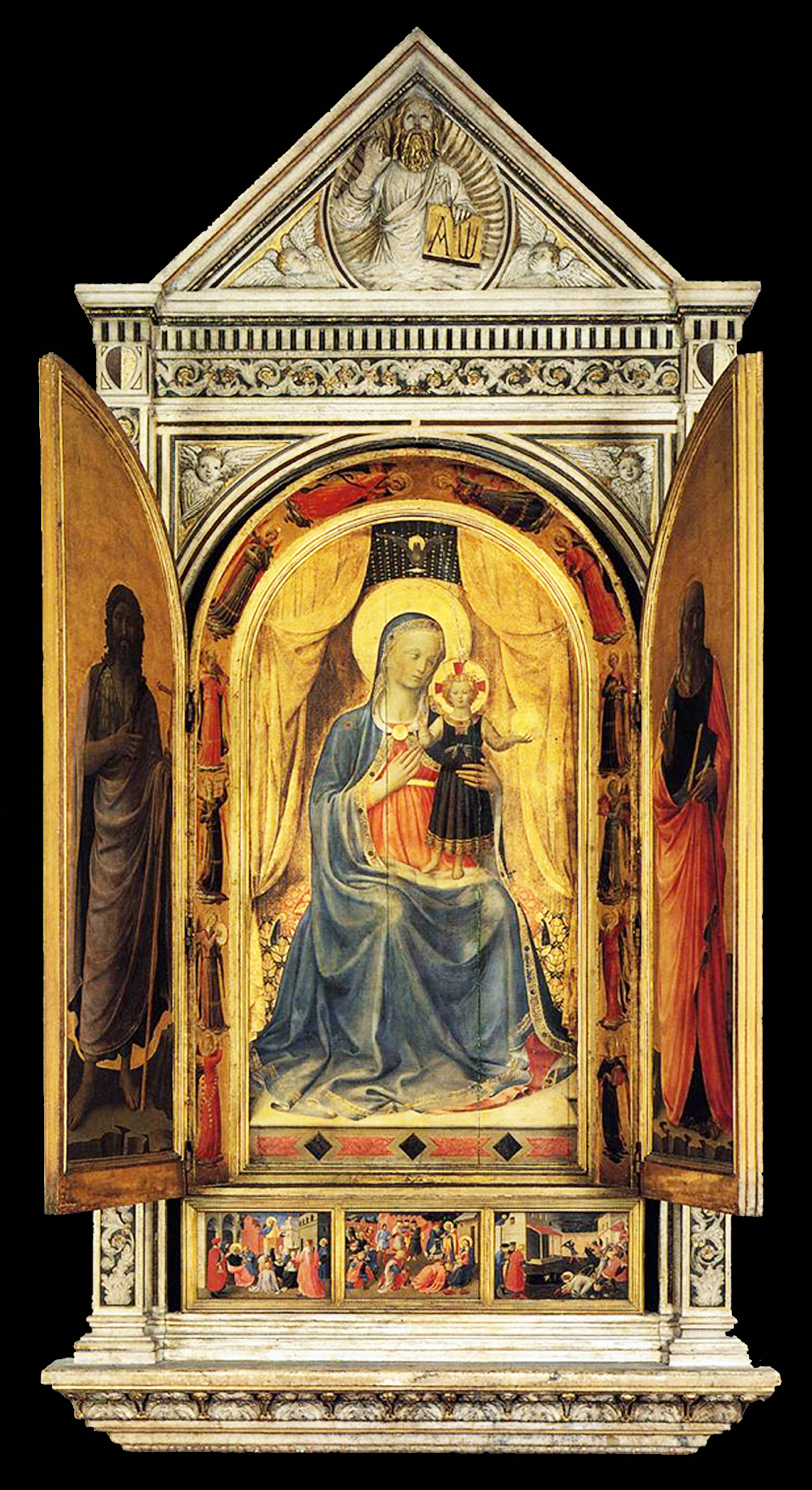

Lorenzo Ghiberti (designer; 1378-1455), Jacopo di Pietro (Il Papero, woodworker), Simone di Nanni da Fiesole (sculptor; 1401-65) & Jacopo di Bartolo da Settignano (sculptor), Fra Angelico (painter; c.1395-1455), Tabernacolo dei Linaioli, 1432-35, main panel 233 x 133 cm., overall size 520 x 270 cm., shutters closed, Museo di San Marco, Florence

Made over a century later, in the 1430s, the Tabernacle of the Linaiuoli (or linen workers’ guild) is a shuttered aedicule on the same premise as Margarito’s 13th century triptych, but notable for its complex construction and for how much is known about its design. This was almost completely in the hands of the sculptor and architect Lorenzo Ghiberti, whose work at this period included designs for the stained glass of the oratory of Orsanmichele, overseeing construction of the dome of the cathedral (the Duomo), statuary, cast bronze reliquaries, designs for the woodwork of the choir of the cathedral, and the design and production of the Baptistery doors [6]. His ability to create and execute objects in very different materials and to varying scales (from the mount of a classical gemstone to the interior of the cathedral) made him the perfect choice to design and supervise the commission from the Linaiuoli.

This was not an altarpiece within a church, but was inset into the exterior wall of the guildhall of linen workers in the Mercato Vecchio, Florence. The shutters were therefore very functional elements of the design, protecting the painting of the Madonna and Child not from the usual degradation of dust, candlesmoke and humid breath, but from the outside air; and since hinged shutters on this scale appear to have been less usual for paintings in Tuscany – especially for those enclosed in a marble frame – but were more likely to be found on ecclesiastical furnishings such as organs, Ghiberti, who had experience in church interiors and furniture, was ideal as the engineer and designer of such a monumental work.

Ghiberti et al., Tabernacolo dei Linaioli, 1432-35, shutters open

What he produced took the form of a chapel opening into the wall of the guildhall, and offering a vision of the Madonna and Child as though enthroned within the hall itself. The size and opulence of the whole work advertized the wealth of the Linaiuoli, their importance to the city of Florence, and the fact that they were under the protection of the depicted saints and of the Madonna; the extent of their wealth, importance and protection being revealed as the shutters were opened. The whole thing – marble aedicule and wooden triptych with predella – was made first, and Fra Angelico was only commissioned as painter after Il Papero had begun work on the interior wooden frames, shutters and panels [7]. The saints on the outside of the shutters are St Mark (patron of the linen workers) and St Peter, and on the inside, John the Baptist and John the Evangelist. Presumably the shutters would be opened if the guild were meeting, or on particularly important feast days, such as St Mark’s Day on 25th April.

Despite these three examples of hinged triptychs from Tuscany – by Margarito of Arezzo, Duccio (of course, a portable work), and Fra Angelico – there seem to be hardly any other examples of full-size altarpieces with shutters in the region: or, perhaps, there are very few survivals. Did the attachments degrade, so that the panels became separated? – or did fashions change, leading to the dismantling of any putative shutters? The closing of monasteries and convents under Napoleonic rule may also have worked its own destruction; but perhaps, too, there were just fewer examples of this type of structure which were produced, and it was a genre which had more popularity in the north of Italy, nearer to the borders with countries which positively fluttered with shutters. Lombardy seems to be the area where there are most traces of shuttered altarpieces (although there are a couple in Rome with the mechanism for covering or removing paintings), but even when there are written references to covers or shutters, the panels themselves are sundered from the altarpieces they once enclosed.

Vincenzo Civerchio (fl. c.1470-1544), portable altarpiece with Annunciation on the outsides of the shutters; SS Benedict and Scholastica on the insides, 1490-95, panel, 46.2 x 32.5 cm. overall, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

This is a small portable altarpiece from Lombardy, produced sixty years after the Tabernacolo dei Linaioli. The fastening of the portelli, sportelli or shutters to the main panel is – as with domestic and portable altarpieces across most of Europe – transparently obvious; there are no paired free-standing columns or tiers of pilasters with exaggerated cornices to get in the way, and the shutters are simply hinged onto the lateral mouldings. There seems to have been a tradition that altarpiece shutters of all sizes would most often have an Annunciation on the outside and appropriate saints (for the area, church or client) on the inside (see below); with the Florentine Tabernacle of the Linaiuoloi, saints were depicted on both sides of the shutters. The central panel is missing in this triptych: a Crucifixion is suggested, although the large Lombardic altarpieces illustrated here all seem to favour the Madonna and Child. It is like Duccio’s early 14th century Crucifixion with SS Nicholas & Gregory in construction and size, although nearly two centuries later, but in style and ornament completely different. For instance, whilst Duccio’s gold ground triptych has the silhouette of a Romanesque basilica, this late 15th century Civerchio is immediately and fully of the Renaissance, deriving its form directly from a Roman funerary altar.

Roman funerary altar dedicated to Iulia Victorina, 1st century AD, Musée du Louvre

It does not pretend to be a chapel or church; it is instead related to the classicizing wall-mounted tabernacles which began to be constructed near altars to contain the sacramental wafers – a sort of holy cupboard – and functions like an architectural window, where the shutters open onto a vision which is less like an appearance of the Celestial Church than a scene happening almost in the same reality as that of the worshipper.

Altarpiece shutters in northern Europe

British or Netherlandish triptych, Life of the Virgin on the inside; Passion of Christ on the outside, 1320-50, silver, enamelled and gilded, open: 7.7 x 13 cm., closed: 7.7 x 6.7 cm., Victoria & Albert Museum

This is another small contemplative object, similar to the Byzantine metalwork triptych shown above, which might be carried on the person and opened like a prayerbook. The metal and enamel which compose it are hard-wearing, but also give it the celestial colour and vividness of a stained-glass window – able to catch the light and give the tiny scenes animation. It is a sort of portable sacred comic, in which each ‘frame’ is set in its own cusped arch, and the whole is surrounded by finely executed stepped mouldings and a line of classical coffering – again like a church window.

British or German triptych, St George and the dragon with engraved figures on the shutters inside, a window with Gothic tracery engraved on the shutters outside, and engraved stonework on the reverse with hanging ring above, silver-gilt and enamelled, c. 1400, open: 5.5 x 6.1 cm., closed: 5.5 x 3.3 cm., Victoria & Albert Museum

A shuttered portable altarpiece might also be a wearable jewel: the triptych above, with a relief golden St George on a silver ground flanked by engraved figures, has a ring at the back of the apex, indicating that it might be worn like a crucifix on a neck or waist chain. This is perhaps the ultimate in portability and access; the hasp could be flicked up, the ‘window’ shutters opened, the saint invoked or kissed, all in a moment, and then everything closed up like a locket to protect the sacred interior. Even in this minute form, however, the connection with church architecture, which was to become more overt and complex through the 14th and 15th centuries, is retained in its structure and in the engraved windows, which open onto the little niche-like shrine with its columns, pitched roof with crockets and cusped tracery in the gable.

Jacques de Baerze (sculptor; fl.pre-1384-post-1399) and Melchior Broederlam (painter and gilder), Le retable de la crucifixion, 1393-96, oak and limewood, gilt and polychrome, open: 167 x 252 cm., Musée des Beau-Arts de Dijon

A full-sized version of a Gothic architectural altarpiece, almost contemporary with the little pendant St George but more than a thousand times larger, the Crucifixion retable in Dijon is one of two carved and painted shuttered altarpieces by the same two artists. They were commissioned in the 1390s by Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, for his foundation, the Charterhouse of Champnol, and now stand alone as surviving Flemish altarpieces of the late 14th century (even so, the painted shutters of the other work have vanished, and the figure of Christ in the scene of the Crucifixion is now in Chicago). Outside, the shutters of this latter work show painted scenes from the life of the Virgin and of Christ as an infant (now separated for display from the main altarpiece), whilst the central sculptural panel inside shows the Adoration of the Magi and the Entombment of Christ flanking the central Calvary.

Jacques de Baerze and Melchior Broederlam, Le retable de la crucifixion, right-hand section and shutter, with a view of Notre Dame de Dijon

The insides of the wings are carved with saints, and the upper tier in each panel is a forest of columns, vaults, filigreed arches and niches holding standing angels. If Duccio’s Crucifixion with SS Nicholas & Gregory of eighty years earlier has the silhouette of a chapel or simple church, this Flemish altarpiece is made in the form of a great towered Gothic cathedral; and the neighbouring cathedral to the Chartreuse de Champnol, Notre Dame de Dijon with its square, tower-like façade, pitched roofs and tiers of arcades, seems the perfect architectural model. De Baerze has elaborated and idealized it, and Broederlam has gilded it from end to end (save for the painted faces and details like the horse and grass beneath the Cross) so that it outshines the stone churches which it mimics [8]. However, the weight of all the carved wood in the wings meant that there was a danger of their collapsing (as the wings of Van Eyck’s Ghent altarpiece apparently began to do at some point), and the Champnol Crucifixion was given

‘…props, at the origin moving along a rail in the pavement; now replaced by fixed props’ [9].

Imagine the breath-taking theatricality of seeing this altarpiece, normally much smaller in width, with a plain border and a few painted scenes, suddenly opened in a great golden embrace of Gothic arches and tracery, filled with saints and angels clustered around the central scene of the crucified Christ, like a vision of the New Testament replayed in Heaven.

Robert Campin (workshop; c.1375-1444), Annunciation (or Mérode) triptych, c.1427-32, open: 64.5 x 117.8 cm., The Cloisters, Metropolitan Museum, New York

There were much more modest works, domestic altarpieces which possibly stood open for much of the time, save for penitential periods such as Lent – since there were none of the liturgical demands on them that there would have been for ecclesiastical paintings. Their frames are relatively simple, although usually well-made: the mouldings around three sides of the panels in the Merode triptych are sculptural and deeply carved, with rainsills on the fourth side which evoke the architecture of a plain hinged window, in keeping with the interior where the Annunciation is taking place.

Robert Campin (c.1375-1444), The Seilern triptych, c. 1425, o/panel, unframed centre panel: 60 x 48.98 cm., unframed wing: 60 x 22.5 cm. (the panels on the back of the wings have been lost), The Courtauld

The frame of the Seilern triptych is even less complex, although its contours suggest the form of a Romanesque church with a barrel vault, where the wings form the outermost aisles of the church. The simplicity of both types of frame, however, informed the style of later altarpieces in which the panels multiplied and developed layers of shutters, allowing different combinations of open and shut wings and tiers of panels to be chosen.

Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400-1464), Last Judgement (Beaune Altarpiece), c.1445-50, 220 x 548 cm. without frames, shown with all wings open and, below, completely closed, l’Hôtel-Dieu, Hospices Civils de Beaune

Rogier van der Weyden, Last Judgement, c.1445-50, opening sequence of panels

For example, the Beaune Altarpiece by Rogier van der Weyden, a pupil of Robert Campin, has four distinct possibilities of open-and-shut combinations. Its frames are extremely simple, allowing the drama of the interior, where the Last Judgement stretches across seven panel-widths and upwards over two tiers, to appear with barely any interruption by the frames of the separate panels. The ‘closed’ panels (the Annunciation, two saints and the donors) have slightly more assertive frames in that they are painted a dull red, and contrast with the light blueish integral shaped niches of the six panels[10].

As with Campin’s work, the emphasis is on the paintings; the minimal frames are more a function of the opening and closing shutters than they are of a decorative or symbolic context. Hélène Verougstraete notes that the two upper wings are attached to the central panel independently of the lower tier of shutters, which gives – besides an additional sequence of openings – more stability to the wings as a whole, and allows the central panel to be given more height. This seems to have been an outcome of the imminent collapse of wings on the Ghent altarpiece [11].

German School, Master of the Burg Weil Altarpiece, Burg Weil Triptych, c.1470, o/panel, 68 1/2 x 60 in. (174 x 152.4 cm.), each wing; 68 1/2 x 26 in. (174 x 66 cm.), shown open, closed, and details of frames in closed and open states; from Württenburg, Metropolitan Museum, New York

There is more decorative attention in what may seem another very minimal set of frames on the Burg Weil Triptych. These are completely flat on the outside, with a small gilt bevel, whilst the colonets and rainsills of the inner scenes have been carefully modelled and painted to emphasize their depth. All the flat friezes are painted red, with flowers in mordant gilding, both echoing and contrasting with the costumes in the paintings and the punched, brocade-like gold ground; these gold on red flowers are characteristic of German altarpieces of the 14th and 15 centuries (and some Netherlandish early works [12]). Even the hinges are decoratively cast. There is a disjunction between the realistic figures of the saints grouped beside the Madonna (although they only gesture at any interaction) and the slightly archaic gold ground, and the same disjunction hovers around the shimmering panels of tracery which hang above them, evoking the cusped and pointed arches of church architecture, and the interwoven foliage of contemporary metalwork. There is no sense that these figures are standing in church niches, however; they are placed on a pavement against some celestial golden hangings, and the tracery merely hangs like another ecclesiastical curtain above them.

It is a large altarpiece, however, and the contrast between the outside – the shutters closed (with the horribly martyred bodies of St Maurice, St Candidus and St Exuperius, and the commanding figure of St Theodulus, who carries the church he built to them at Saint-Maurice in Switzerland) – and the effect of the shining golden scene when the shutters were opened must have been almost other-worldly. When freshly executed the brilliance of the gilded ground and painted colours, the tracery, and the (now very faded) garlands of golden flowers would have shone out dramatically from a candlelit altar.

Michael Pacher (c.1435–d.1498), St Wolfgang altarpiece, 1471-79, installed 1481, polychrome pine, shown with the carved Coronation of the Virgin open (top), and with all the painted shutters on view (below), Parish church, Sankt Wolfgang, Austria

The full bloom of the shuttered altarpiece in central Europe took the plain frames of the previous two examples and married them to extraordinary fantasies of towering filigreed spires and canopies in the style of the Champnol Crucifixion – no longer contained within the altarpiece itself, but soaring upwards, like the cover of a Gothic font. St Wolfgang, Bishop of Regensburg, has at least two and possibly more of these confections to his name, one in the parish church of Sankt Wolfgang (above), and one – the Kefermarkt altarpiece – in the parish church of Kefermarkt, Austria.

The altarpiece in Sankt Wolgang is an assemblage of limewood sculptures, tiers and wings of paintings, surpassing even the Champnol Crucifixion in its breath-taking effect, with an additional carved and painted shuttered predella as well as its crown of figures and finials: all the work of a single carver and painter, Michael Pacher [13]. Like the Beaune altarpiece, it has several layers of appearances, so that the central boxed altarpiece can be closed completely, showing four painted scenes from the Life of St Wolfgang; these can be opened to show eight painted scenes (above) from the Life of Christ. The boxed scene is a sculptured Coronation of the Virgin beneath a three-dimensional intricately pierced canopy, which appears to continue up, through the top of the box, into the airy spires above it, which hold a scene of the Crucifixion and saints. The carved predella holds an Adoration of the Magi, with shutters showing painted bishops and Gothic arcades.

The engineering required for this origami-like inter-folding of shutters, with enough strength to support their movement across the central box and back again in two movements, is admirable enough in itself [14], not to mention the paradoxical illusion of the spire which reaches up from the canopy over the Coronation in Heaven to the scene of the Crucifixion on earth. It is a whole small church in itself, or a magisterial conjuring of the Celestial Church – a wooden metaphor for the multiverse [15].

Jan Gossaert (c.1478-d.1532), Malvagna triptych, o/panel, 1513-15, 46 x 35 (centre panel), 45 x 18 cm (each wing), Galleria Nazionale della Sicilia, Palermo

Ethan Kavaler notes the development of the kind of non-classical, flamboyant Gothic ornament seen in these Burgundian, German and Middle European altarpieces as it diffused in the Netherlands through various associated architectural genres, from church façades to frames, monumental sculpture and church furnishings:

‘Accomplished conceits were readily adapted to works of widely differing scale, from the monumental towers of churches to the carved tabernacles above statues or the miniature spires of gold reliquaries… This Gothic manner developed across several media, as designers collaborated with… trained craftsmen… A nearly exclusive interest among historians of Netherlandish art in painting of the period has partly obscured such interdependence. It is worth recalling that Gossaert, van Orley, and Lancelot Blondeel designed stained glass, tombs, and other architectural projects…’ [16]

He uses as an example the altarpiece above, the Malvagna triptych, which

‘…opens to reveal a miraculous world in miniature… above [the figures] hover massive canopies of intricate and finely crafted Gothic tracery…’

Here, particular repeated motifs in the tracery echo and vary each other, helping to unify the trompe l’oeil painted stonework and

‘establish a hierarchy of ornamental devices… Significantly, the three baldachins on the wings and the central panel are all distinct… The value placed on such variation is attested by a contract of 1507 between the brewers’ guild of Louvain and Jan Borman, the …sculptor… [He] and his assistants were required “to make the middle tabernacle entirely different [from those in the side bays] though as expertly as indicated in the plan.” ’ [17].

Gossaert’s inventiveness was influential, and was copied by numerous painters, making its way into various illuminated manuscripts; it helped to spread a genre of trompe l’oeil painted architectural tracery which had been established much earlier in the settings of three-dimesional carved altarpieces.

Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400-1464), Seven Sacraments altarpiece, 1445-50, 200 x 223 cm., and detail of painted altarpiece within it, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts, Antwerp

One of the important elements of these repeated and echoing ornaments was the ogival arch, which had also been adopted much earlier as a structural contour for the panels and shutters of altarpieces. The Seven Sacraments altarpiece by Rogier van der Weyden has a meticulously painted altarpiece in the background of its central panel, which combines a carved retable at the base and a filigree spire at the top, both suggesting the complex traceries which Gossaert adopted more than half a century later in his paintings. It also encloses the large central sculpture of the Virgin within a set of painted shutters with ogival heads, which can fit into the arched drops of the spire, forming a complete tabernacle to protect and conceal her.

Maître de 1473, Triptych of Jan de Witte, 1470s, o/panel, central panel: 74.5 x 38.7, shutter panels: 74.5 x 38.5 cm., Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

Joachim Patinir (fl.1515-d.1524), Penitence of St Jerome, c.1512-15, o/panel, central panel with engaged frame: 46 ¼ x 32 (117.5 x 81.3 cm.), each wing with engaged frame: 47 ½ x 14 ins (120.7 x 35.6 cm.), shown open and closed, Metropolitan Museum, New York

The ogival arch became particularly popular for 16th century Netherlandish altarpieces, remaining after the complex of canopies, valances and spires of tracery had fallen away. The ogees generally came to be reversed from the cusped arches painted in the Seven Sacraments altarpiece, and framing, for instance, the Triptych of Jan de Witte (top); this reversal created a softer S-curve meeting in a round head, as in Patinir’s Penitence of St Jerome, still in its original frame. The S-shaped mouldings give these shuttered retables their defining silhouette when opened, and perhaps give greater reason for their being labelled ‘winged altarpieces’.

Joos van Cleve (c.1485-1540/41), Annunciation, c.1525, o/panel, 34 x 31 ½ ins (86.4 x 80 cm.), and detail of domestic altarpiece, Metropolitan Museum, New York

In Joos van Cleve’s panel of the Annunciation (possibly itself once the centre of a triptych, as the museum’s catalogue entry suggests), the Virgin is discovered at her prie-dieu in a comfortably furnished and obviously contemporary bedroom. It includes a domestic altarpiece in the form of a diptych with an ogival arch at the top, crested with ornate crockets and finished in two shades of gold leaf, with a partly black-painted inner frame, and red-painted outer frames around the grisaille shutters, matching the shaped base. It echoes Patinir’s Penitence of St Jerome, although quite a lot smaller, and is evidence of the abundance of these personal altarpieces – also of their form and finish, and of the effect of opening the shutters onto a brightly painted Biblical landscape and parcel-gilt frame.

The museum entry quotes Lynn Jacobs:

‘Inventories of household goods mention small triptychs that were displayed on top of wooden cabinets or kept within them until they were brought out for use…’ [18]

Nicolas Froment (Provençale school, c.1425-1483-86), Matheron diptych, 1475-1525, 18 x 13 cm., shown open and with outside of shutter, plus original storage bag, Musée du Louvre

Domestic diptychs might also be displayed on cupboards or tables, or placed

‘on the inclined plane of a prie-dieu, or on a cushion… then reclosed and stored in a box, sometimes locked, or in a bag or cover. Only rarely do we find diptychs complete with bag, such as the Matheron Diptych, attributed to Nicolas Froment, representing René of Anjou and Jeanne de Laval, c.1476…’ [19]

A shuttered altarpiece in Spain

Jan (c.1500-1556/57) and Katharina (b.1527) van Hemessen, Tendilla Retablo, 1550s, o/panel, open: 139 ¾ x 180 ins (355 x 427.2 cm.), Cincinnati Art Museum

The paintings of the Tendilla Retablo are by the Flemish artists Jan van Hermessen and his daughter Katharina, and must have been painted before Katharina moved to Spain with her husband in 1556, as she seems to have ceased painting on her marriage. However, both she and her father had Spanish patrons (Maria of Austria and her brother, HRE Charles V, respectively), and the altarpiece was probably commissioned by a member of the Castilian aristocracy (v. the armorial bearings on the frame) who was attached to the Habsburg court in Flanders. The frame was made in Spain, however, either by migrant Flemish craftsmen or indigenous carvers. It displays elements from both countries, and is one of the few winged retables to be executed in Spain, where the design of altarpieces and their frames differed from those elsewhere in Europe [20].

Façade of Sancti Spiritus, University of Oñati, 1540, SE of Bilbao, northern Spain

The inside of the retable has a lot in common with Spanish Renaissance architecture in the Plateresque style, where a classical structure is overlain with complex layers of intertwined ornament, columns growing from baluster shapes and ringed with clasps, round-headed arches with bands of cherubs’ heads, large finials, decorated modillions and Gothicizing canopies. It is a version of Mannerism, and by itself this inside section would be almost entirely Spanish; however the wings are Netherlandish in style, in their shape, and the way that they fit into the rest of the structure. Like the Champnol Crucifixion, which blends French and Netherlandish approaches, the Tendilla Retablo is an example of stylistic influence moving between countries as rulers moved, and as craftsmen moved with them.

Altarpiece covers in Italy (portelli)

In his article on the various coverings for 16th century north Italian altarpieces, Alessandro Nova considers stylistic influence in another area of Europe. This involves some of the larger, specifically Lombardic works which he classes as Flügelaltäre, or altarpieces with wings and shutters, along with the many examples of such things in Flanders, the Netherlands and Germany, and which are therefore inevitably imagined by his reader as similar in form to the Van der Weydens, Pachers and Patinirs illustrated above – or at least as an enlarged version of the Civerchio portable altarpiece [21]. Because physical evidence of these shutters has now all but disappeared, the examples he cites are reliant on historic accounts: notably a manuscript by the 17th century soldier turned priest, Bernardino Faino, a catalogue of the churches in the diocese of Brescia with their paintings and sculpture, and a similar guide from the 18th century on the glories of Brescia [22].

Professor Nova quotes in particular references to Titian’s Averoldi altarpiece (1522):

‘the work was covered by two ante dipinti’ [painted panels which stood in front of the main altarpiece]…

…and to Girolamo Romanino’s Sant’ Alessandro altarpiece (c.1524), which

‘…was once a Flügelaltar with an Annunciation on its exterior and an Adoration of the Magi visible when the shutters were open’ [23].

Unfortunately both polyptychs have lost their original settings, the Titian having been reframed in 1824-26 and moved behind the high altar of SS Nazaro e Celso, Brescia, and the Romanino having ended up in the National Gallery, London, missing its Pietà from the top and acquiring an unsuitable frame made after its purchase in 1857.

Girolamo Romanino (c.1485-c.1566), Sant’ Alessandro altarpiece, c.1524, o/panel, centre 265 x 117.2 cm., lower lateral panels 159.7 x 64.2 cm. & 159.1 x 64.8 cm., upper panels 74.2 x 65.2 cm. & 74.2 x 64.9 cm., 19th century British Renaissance revival frame, National Gallery, London

The loss of both these frames makes it difficult to be certain how their shutters would have been attached and operated, especially within the grand aedicular altarpiece frame which the Romanino certainly had; perhaps they were not really ‘winged’ altarpieces at all, but were covered in some other way by their painted ‘doors’ (Professor Nova does point out that the words ‘cortina’ or blind-like curtains and ‘portelli/sportelli’ or shutters can be swapped in their use, and also confused with curtains in the sense of hangings around an altar [24]). It is known that the missing frame for Romanino’s Sant’ Alessandro polyptych was made by the Brescian master carver, Stefano Lamberti, whose powers of composing an aedicular frame on the grandest of scales, marshalling three dimensional architectural elements and relief sculptures around it, and marrying these with the most delicate and imaginative of carved ornaments, are breathtaking. However, other works by him have fortunately survived for comparison.

Stefano Lamberti (1482-1538), frame, 1502, and Girolamo Romanino (c.1485-c.1566), painted panel, Pala di San Francesco, c.1517, San Francesco, Brescia. Photo: RobyBS89

One is this extraordinarily beautiful and richly carved altarpiece which remains in situ in the church in Brescia for which Lamberti made it in 1502, although the painting it contains is a later cuckoo, the original commission having been intended either for Bernardo Zenale or his teacher, Civerchio [25]. Professor Nova quotes Carlo Ridolfi (1594-1658) on this very altarpiece:

‘…on the two shutters that cover it appear the seraphic saint marrying Poverty and, beneath, the bishop of Assisi preaching to the people imploring indulgence of the Madonna of the Angels, and the dreaming pope holding a vial into which the saint drops blood from his rib, and on the other side the expulsion of monstrous demons from Arezzo signifying the discord of those times between the Guelph and Ghibelline factions . .’ [26]

If the frame of Romanino’s Sant’ Alessandro altarpiece was on a similarly magnificent scale (a sculptor of such skill having been employed for both makes it pretty certain), then there were at least two altarpiece frames in existence with unusually deep profiles and jutting cornices above the free-standing columns, and reports of two sets of shutters or masking paintings. But looking at the San Francesco altarpiece above, how would it have been possible to attach two hinged doors to this extravagant façade so that they could cover the whole painted panel when shut, but could also be opened to allow the insides of the shutters to be visible? The sides of the frame are wide, with their paired free-standing columns, and it seems much more likely that the ‘shutters’ (‘portelli’ or ‘sportelli’) – or even the paintings themselves – were slid sideways on tracks inside or in front of the altarpiece, as seems to have happened with some Roman examples (see below). Hinged shutters would have had to be so intricately shaped on the attached sides to accommodate the projecting cornices as to make them unfeasibly delicate, and needing perhaps to revolve on a spindle in the top of the cornice, and they would probably need to be of canvas stretched on battens rather than wooden panels. It’s a pity that Ridolfi didn’t stop to consider and describe the mechanism of the altarpiece, as well as the images.

Stefano Lamberti (attrib.; 1482-1538), frame, and Girolamo Romanino (c.1485-c.1566), painted panel, Altarpiece of Santa Giustina, 1513, 400 x 262 cm., Museo d’Arte Medievale e Moderna di Padova

The Altarpiece of Santa Giustina, painted for the eponymous Benedictine monastery in Padua, features another of these enthroned Madonnas. It combines Romanino’s painting with Stefano Lamberti’s carving, although in this case Romanino was definitely the commissioned artist, and the painting of the coffered niche or chapel where the Madonna sits beautifully reflects and continues the exquisite carving of the frame. Once more the fixing for any putative hinged shutters seems problematic. The museum entry reveals that Romanino ‘was already known to the fathers of the Paduan monastery, having painted the doors of the church organ, which have been lost’; and Professor Nova notes that organ shutters were much the same shape and had the same painted subjects (Annunciations and appropriate saints) as the shutters of altarpieces.

Giovanni Giacomo Antegnati (b.1501), organ, c.1536 (restored by Serassi, 1826), painted by Girolamo Romanino (c.1485-c.1566), c.1536, shutters shown closed and open, Cathedral of the Assumption and S. Andrea, Asola

He adds that,

‘…the possibility must be considered either of a switch or of a confusion between organ and altar shutters. The two categories are very alike: one is dealing with very large canvases carried out a guazzo [‘tempera low in fat content’], painted with the same subjects…’[27]

However, it seems that, looking at the frames alone, there cannot be such confusion between these two types of ‘shutters’. To start with, the shutters on the organ at – for instance – Asola must have had the painted canvases mounted onto the wooden doors – or else the paintings have been executed directly on the wooden panels (as Romanino painted panels of the Asola pulpit). Secondly, the shutters are hinged at the outer sides of the pilasters, and when closed they cover the carved wooden pilaster panels with trompe l’oeil panels which form the two lateral borders of Romanino’s paintings.

Left-hand shutter of the organ in Asola

The upper corners of the shutters next to the hinges have indeed been cut away to accommodate the capitals, as have the bottom corners which move across the pilaster pedestals. But this is a relatively simple arrangement – easy to make and to operate across the flat façade of an uncomplicated Renaissance aedicule, which is basically two architraves and a lintel – but practically impossible when considering the tiered pilasters, free-standing columns and multiple layered cornices of Stefano Lamberti’s altarpieces.

The evidence from Rome – apparently sole survivals which seem to indicate how altarpieces might be removed from view within Stefano Lamberti’s intricate settings – points to a form and method of use quite different from the hinged shutters of organs. Rather than the altarpiece opening like a cupboard, this is much more like the arrangement for moving scenery flats in a theatre, using pulleys which cause them to shunt along metal tracks at the bottom and top.

Giovanni (?) Torelli, Assumption of the Virgin, 1716, Chapel of the Most Holy Sacrament, SS Giovanni e Paolo, Rome

The altarpiece above apparently used to be sited in the next chapel along in the Roman church of SS Giovanni & Paolo, which is now known as the Chapel of Christ’s Passion and contains a Crucifixion by Tommaso Conca (1734-1822). All the chapels are identical, but were shuffled about in the 20th century, and the church itself was extensively remodelled in about 1718, so that the mechanisms for moving the paintings are therefore either early 18th century inventions, or updated iterations of previous installations. Since they are operated behind the back walls of the chapels by tracks and pulleys, it would be satisfying to think that the painter of this particular work is a close relative of Giacomo Torelli (1608-78), a Venetian set designer who worked (coincidentally) in the theatre of SS Giovanni & Paolo in Venice, where he used a system of counterweights to work the scene changes, and used backdrops running on pulleys to alter the configuration of the stage [28].

Details of the installation behind the Torelli altarpiece in SS Giovanni e Paolo (left and right predicated on a view from the front of the altarpiece). Photos and information: with many thanks to Marc O.Manser

It is difficult to make it clear how this works, but imagine that there is a cupboard clamped to a thin wall behind the altarpiece, with a slight gap in front of it into which metal tracks feed at the top and bottom. The altarpiece painting can be slid sideways on these, out of the frame, leaving behind it the open cupboard, which held a carved throne, now in the church museum, against a background of some kind. This was apparently displayed on feast days. Possibly, in the past, two narrower covers (‘portelli’, doors or shutters) might have been slid in front of the painting, one from either side, but there is now nothing to confirm this.

One of the other altarpieces has a rope pulley, by which means a piece of painted fabric might be rolled down over the altarpiece. See Part 2 of this article for curtains and blinds of this kind.

Stefano Lamberti and Girolamo Romanino, Altarpiece of Santa Giustina, 1513, Museo d’Arte Medievale e Moderna di Padova

The use of such mechanical methods to slide an altar painting from its frame – or to cover it – might explain why there is a step supported on a modillion jutting out from either side of the Santa Giustina altarpiece: an otherwise inexplicable element of the frame, but which might be used to help to thread putative covers in front of the painting (‘ante dipinti’). It might also be used to support the ‘open’ dipinti (perhaps with the help of movable wooden or metal supports at the outer ends: cf. the Champnol Crucifixion) as though they were hinged shutters supplying the same element of revelation; then, if they stood at a wide angle to the altarpiece, their inner painted surfaces would also be visible.

Over the decades and the centuries, the mechanisms by which these covers or portelli were moved in front of or away from the large architectural altarpieces with which they were associated may have faltered or worn out, the disassembling of the different parts being hastened by Napoleon’s depredations amongst churches and monasteries, and by the need of their owners to sell, and of predatory dealers to buy. There may be many panels (i.e. canvases which functioned as shutters and covers) which are now framed as autonomous paintings and have lost all connection with the altarpieces with which they had such a dynamic relationship; and the lack of much art historical research on where and when and how they did function in this way may have further fogged the picture.

Certainly, most large altarpieces with hinged shutters are now displayed as fixed polyptychs, like the triptych by Margarito and Ristoro d’Arezzo, for fear of damaging the individual panels or the overall work (although sometimes they may already have been sliced apart vertically into backs and fronts of shutters, or otherwise parted into smaller configurations, even if this means the destruction of the narrative themes through movement and revelation of the altarpieces). Perhaps the museum, as a mainly static collection of ‘masterpieces’, has removed any expectation of seeing works of art change and interweave to create different relationships and produce different emotions; but although the paintings may endure longer if preserved like butterflies on pins, something else – inherent to their creation and raison d’être – may well have been thrown out with their mechanisms and movements.

*********************************************

Early 20th century Gothic revival altarpiece by Rattee & Kett, shuttered for Lent in 2010 and open; Lady Chapel (consecrated 1910), Liverpool Cathedral. Photo of shuttered state: Rex Harris (detail)

Designed by G. F. Bodley (1827-1907) and George Gilbert Scott the younger, made by [James] Rattee & [George] Kett (1843-2011), with reliefs from models by G.W. Wilson.

*********************************************

With grateful thanks: The section on the mechanisms behind the altarpieces in SS Giovanni e Paolo in Rome owes a huge debt to Marc O. Manser, who very kindly went and looked and asked and photographed. The initial pointer to this church came from Anthony Majanlahti.

*********************************************

[1] An earlier example (778-820) is the Lorsch Gospels or Codex Aureus of Lorsch, which has been split over various locations; part in Romania; part in the Vatican Library, including the ivories from the back cover The ivories from the front cover are in the V & A

[2] History of the Pala d’Oro. This altarpiece has been used as a dossal or reredos for most of its life, but started out as an altar frontal

[3] Laura Moretti, ‘Architectural spaces for music: Jacopo Sansovino and Adrian Willaert at St Mark’s’ (transl. Hugh Ward-Perkins), Early Music History, vol. 23, 2004, p. 157; she is quoting James Moore in various articles

[4] See the report on the restoration of the back cover by Maffeo da Verona under the auspices of the Save Venice organization

[5] See ‘An abbreviated history of Italian frames from the 12th to the 20th century’

[6] Entry for Ghiberti, Treccani Dictionary of Biography of Italians, vol.53, 2000

[7] Creighton Gilbert, ‘Painters & woodcarvers in early Renaissance Italy’

[8] See, also, altarpieces such as that by Rupert Potsch & Philipp Diemer, Altarpiece, 1506-c.1509, from Brixen (previously Austria, now Bressanone in Italy), parcel-gilt polychrome and limewood 416 x 465.5 cm. open, V & A

[9] Hélène Verougstraete, Frames and supports in 15th and 16th century Southern Netherlandish painting, 2015, p. 122. The wings of the Ghent altarpiece were apparently cut down in order to solve the weight problem, which had afflicted a Deposition by Jan Gossaert (lost in a 16th century fire) to such an extent that the open shutters had to be supported on trestles (ibid., pp. 124-25). Many of the panels of the Ghent altarpiece have been reframed (some as many as five times); other frames have been altered or otherwise compromised (ibid., pp. 192 ff.).The lower, original frames are inset with little wheels at the base, to help with the opening and closing process

[10] Hélène Verougstraete includes a section, illustrated with diagrams of closed and opening diptychs and triptychs, which demonstrates how the painted light effects worked to further the illusionism of the faux stone niches which so often decorate the shutters of altarpieces, and contain the figures of saints in grisaille, or donor portraits: ‘the lighting is almost always consistent’ – i.e. coming from the left side for diptychs, or more obliquely from the left centre for triptychs – and appears to move in conformity with the opening or closing of the shutters (ibid., p.164-65)

[11] Ibid., pp.122-23

[12] Ibid., p. 158

[13] There is also the possibility that Pacher’s brother may have painted the St Wolfgang shutters

[14] Hélène Verougstraete has a chapter on ‘Hinges. Closing, hanging and positioning systems and devices’, op. cit., p. 103 ff

[15] Van Eyck’s Ghent altarpiece seems to have had a similar spire of tracery above its painted panels; it also had a predella which was destroyed by Calvinist iconoclasts (ibid., p. 215 ff.)

[16] Ethan Kavaler, ‘Renaissance Gothic in the Netherlands: the uses of ornament’, The Art Bulletin, vol. 82, no 2, June 2000, p. 228 ff

[17] Ibid., p. 229

[18] Lynn F. Jacobs, Opening doors: The early Netherlandish triptych re-interpreted, 2012, pp. ix, 17, 50, 296 n. 98, fig. 3

[19] Hélène Verougstraete, op. cit., p.169

[20] Spanish altarpieces in Gothic-Renaissance style of the 15th and 16th centuries tended to be large, flat polyptychs, which grew ever more vast, often filling the entire east end of a chapel, church or cathedral. The rather smaller versions were protected, not by winged shutters, but by a wide canted dust-guard or guardapolvo, which projected like a steep back-sloping porch, all the way round the top and sides of the altarpiece: for example, in the Capilla de Santa María de Jesús, Seville

[21] Alessandro Nova, ‘Hangings, curtains and shutters of 16th century Lombard altarpieces’, in Italian altarpieces 1250-1550: Function & design, ed. Eve Borsook & Fiorella Gioffredi, 1994, p. 183

[22] Bernardino Faino (1600-73), Catalogo delle chiese riverite in Brescia et delle Pitture et Scolture memorabili che si vedono in questi tempi (Biblioteca Queriniana, manoscritti E. VII, 6 e E. 1.10), edited and published by Camillo Boselli in 1961 as Catalogo delle chiese di Brescia; F. Maccarinelli, Le glorie di Brescia, 1747-1751 (Biblioteca Queriniana, manoscritti I. VIII. 29, and G. IV. 8), published, also by Camillo Boselli, in 1959

[23] Nova, op. cit., pp. 183-84, quoting Maccarinelli, ibid., p. 154

[24] Ibid., p.178-79

[25] Creighton Gilbert, ibid.

[26] Nova, ibid., p. 184, quoting Carlo Ridolfi, Le maraviglie dell’arte ovvero le vite degli illustri pittori veneti e dello stato, ed. D. von Hadeln, 1914 (first published 1648)

[27] Ibid., pp. 185-86

[28] Entry for Giacomo Torelli,Treccani Italian Encyclopaedia

[…] Beyond it is the high altar, with the priest raising the Host at the moment Christ’s death occurs behind him; and on the altar is a carved and stepped retable (either of stone or wood), echoing the shape of the altarpiece in which it is painted, and full of figures of saints and bishops under traceried Gothic canopies. A pillar rises behind it, supporting a sculpture of the Madonna and Child which is probably carved in wood, and is painted and gilded. This sculpture can be enclosed by a series of shutters, painted inside with scenes from (?) the life of the Virgin, and is topped by a pendant three-dimensional spire of tracery. The whole thing is executed so faithfully, with so much volume and detail, that it could almost be reproduced just from this rather occluded view alone. It bears witness to the number of contemporary altarpieces in different or combined materials, overlapped by finishes in gilding and polychromy which could appear on both wood and marble, as well as on flat painted panels. It also shows how far from static these objects could be, as they responded to liturgical needs by opening or closing themselves up from public view (see also ‘An introduction to frames with covers, shutters and curtains. Part 1: Covers and shutters on sacred …’). […]

LikeLike

Oh, Lynn, your articles are so pleasant for me!

Thank you very much!

LikeLike

[…] second of a triptych of articles; the first, on shutters and covers of sacred works, is available here. This present one explores curtains around the outside of altarpieces, painted curtains inside […]

LikeLike

Very interesting and detailed article. There are unique pictures. Fascinating the covers of the old books, all decorated and with the purpose of protecting something precious.

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind comment; I’m so glad that you enjoyed the article.

Lynn

LikeLike

Magnifique, your emails are treasures 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you; how kind of you! I’m so glad that you enjoy them… 🙂

LikeLike