Edvard Munch: ‘They forbid me to make my own frames’

by The Frame Blog

by Marei Döhring

‘They forbid me to make my own frames’, [1] Edvard Munch wrote in 1906, notably in German and not Norwegian, providing no additional context regarding the identity of the elusive ‘they’. This enigmatic statement implies that the artist’s frames were not particularly well received by some of his contemporaries, and it is indeed revealed from several other sources that Munch’s frames have frequently been a subject of discussions and disputes. But what sparked such controversy surrounding his frames? In this paper, I aim to establish what Munch’s preferred frames looked like, examine how they were received by the public, and discuss the reasons for his choice of frames.

The ‘Commeter Affair’

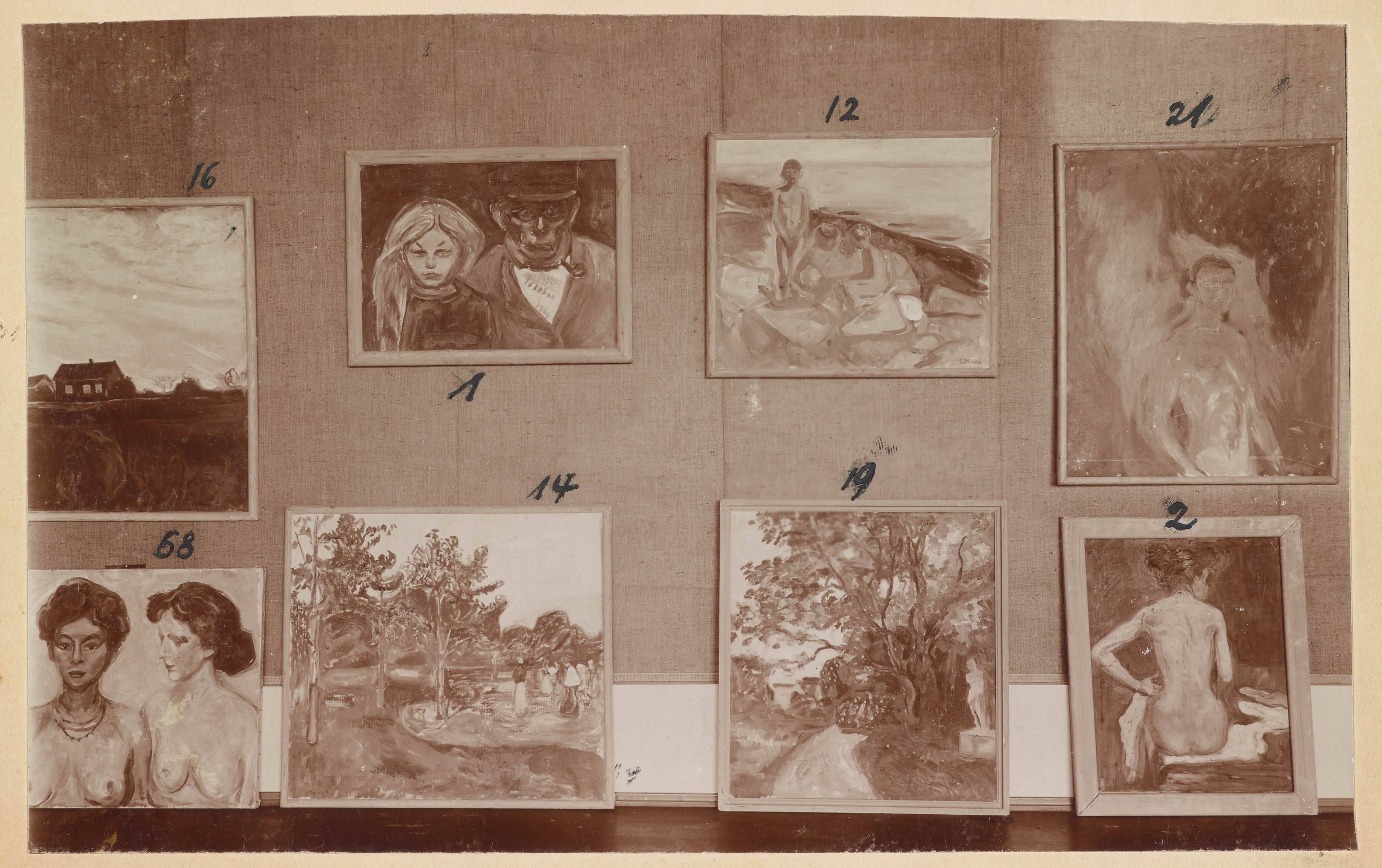

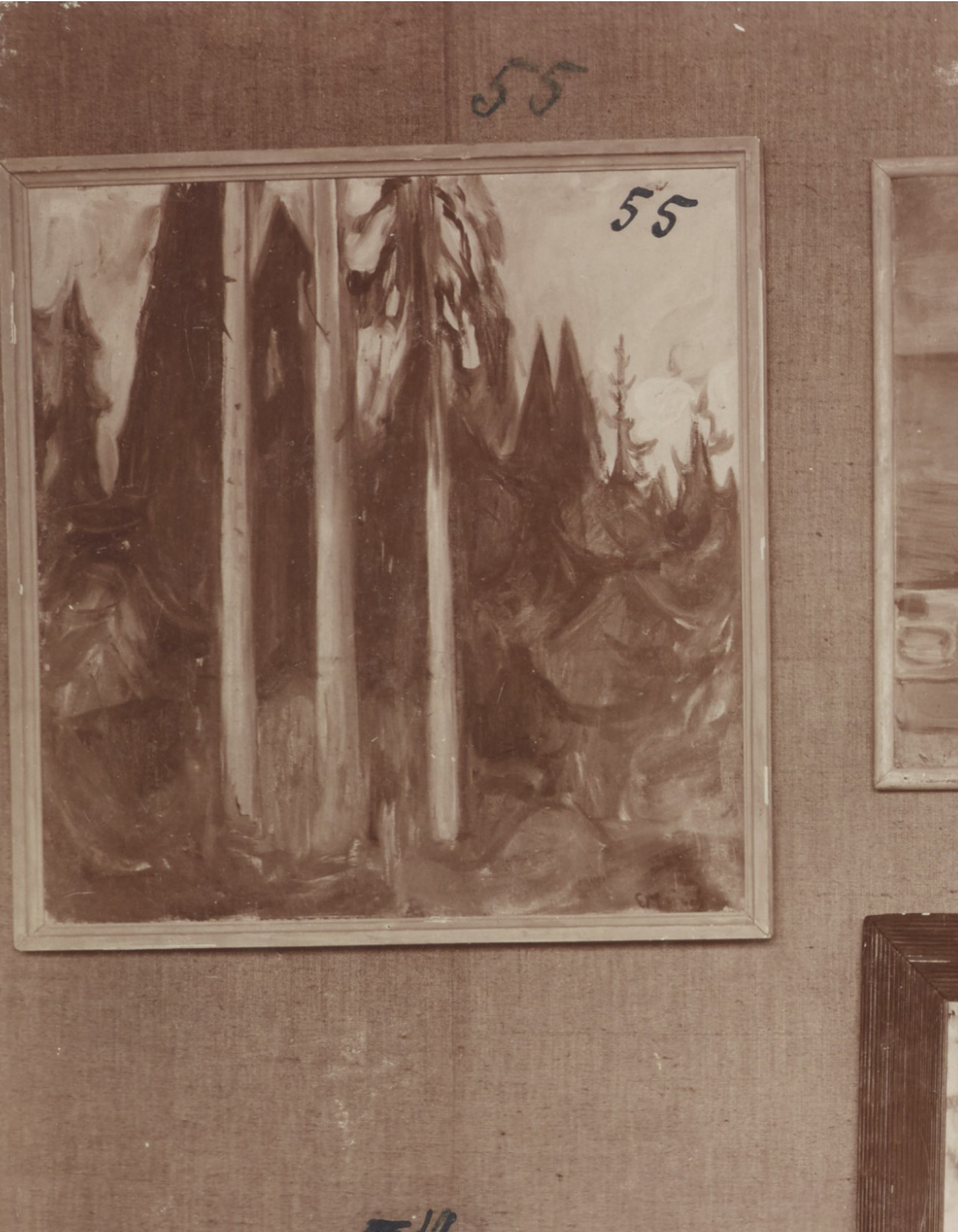

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), paintings hanging pre-exhibition at Galerie Commeter, Hamburg. Photo: Atelier Schaul, 1906, MM.B.01816K, ©Munchmuseet

In 1906, the same year that Munch wrote the note mentioned above, the artist expressed his discontent in a letter to his friend, the collector and art critic Gustav Schiefler:

‘The Commeter Morocco affair is heating up – and war is threatening to break out – joking aside – he is really unpleasant …’ [2]

By ‘The Commeter Morocco affair’ Munch was referring to a lengthy and heated argument between himself and Wilhelm Suhr, the managing director of the Hamburg art gallery Commeter, which also encompassed discussions about the artist’s frames. In March 1905, Munch had signed an agreement with Suhr to exhibit and sell his paintings in the gallery. However, upon the arrival of the paintings in Hamburg, Suhr made his first complaint to Munch in April 1905:

‘I must inform you that several paintings are damaged as a result either of bad packing or bad treatment in Prague, some works showing direct nail holes in the canvas… The majority are unframed, while the rest of the paintings have frames which are battered to such an extent that at this point an exhibition is unthinkable’.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), paintings hanging pre-exhibition at Galerie Commeter, Hamburg. Photo: Atelier Schaul, 1906, MM.B.01816C, ©Munchmuseet

He continued:

‘If you can’t travel [to Hamburg] now, I would ask you to write to me as to how you would like the pictures framed, or would you prefer to leave this to me?… I am writing this to you in your own interest!’ [3]

In another letter, Suhr provided further details of the damage to the frames, stating:

‘The mouldings, by which I mean the frames, are – apart from the dirt covering them – full of nails. The mitres of these ‘frames’ are simply hammered together with one or two nails, usually so that the points are visible’.[4]

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), paintings hanging pre-exhibition at Galerie Commeter, Hamburg. Photo: Atelier Schaul, 1906, MM.B.01816aF, ©Munchmuseet

In 1906, Munch’s paintings were photographed at Commeter. Even in the black-and-white photographs it is evident that the corner joints were already coming apart in some examples, and many of the frames exhibited visible dirt and damage. Looking at them now, it is easy to sympathize with Suhr’s concerns. The gallery director was clearly worried about his reputation (and probably his sales) when he wrote:

‘I have furnished my rooms very well and [it] would simply be impossible for your paintings to be displayed in them, not to mention the fact that I cannot be held responsible for this to the public’. [5]

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), paintings hanging pre-exhibition at Galerie Commeter, Hamburg. Photo: Atelier Schaul, 1906, MM.B.01816G, ©Munchmuseet

A week later he insisted once again:

‘I owe it to my audience, which is mostly very sceptical about your pictures anyway, that a picture is at least properly framed (whether simply or richly decorated)…. and does not look like lumber!’ [6]

Suhr’s aim in displaying Munch’s paintings in more acceptable frames was probably not only to cater to bourgeois tastes, but also to minimize the scandalous impact of some of Munch’s subjects on the public. In 1892, an exhibition of Munch’s works at the Verein der Berliner Künste famously caused such outrage that it had to be closed ahead of schedule. Although the scandal had contributed to Munch’s fame, Suhr presumably wanted to avoid similar incidents in his own gallery. Unfortunately, Munch’s replies have not been documented. However, Suhr’s assertion that,

‘Of course you shall retain the right to choose the frames for your paintings in the future’, [7]

indicates that Munch objected to any interference from the gallery director.

Who is in control?

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Puberty, 1894, in three incarnations of frame: the battered original, the same repainted (archival photo, date unknown, MM.B.03423, ©Munchmuseet), and present day in the Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo

The dispute between Munch and Suhr raises broader questions about agency. Who holds the authority to determine the framing of artworks – the artist, the gallerist, or perhaps the collector?

The battle for sovereignty in controlling the framing and general presentation of artworks became substantially more intense from the second half of the 19th century onwards. Artists, particularly those associated with the avant-garde, increasingly challenged traditional framing methods and bourgeois sensibilities. At the same time, the resurgence of creative interest in the frame was closely tied to profound changes within the exhibition industry. With the rise of a more international art market and artists gaining greater independence from patronage and academic institutions, the frame had become free to be (re)claimed by the artists themselves.

Beyond their role in protecting and embellishing paintings, frames became symbols of the artist’s control over their creative work and its public display. Ambroise Vollard remembered that Edgar Degas once withdrew one of his paintings from a collector because the new owner had dared to replace the artist’s frame with a design of his choosing [8]. Vollard’s anecdote encapsulates the growing sentiment among many artists at that time, who viewed presentation as an integral part of their creative expression.

Practicality over aesthetics?

Despite this, Munch’s strong objection to new frames was undoubtedly influenced by financial considerations as well. According to the agreement, Munch was responsible for the cost of new frames, which is why Suhr offered to have some of the frames repaired and repainted to save on costs[9]. By the late 19th century, frames had become a significant expense for modern artists. Instead of exhibiting only a few of their most prestigious pieces at a time, in the more famous annual Salons, modern artists often showed numerous works simultaneously at various venues. To compete with their peers, they had to keep up with the latest styles and ever-evolving ‘–isms’, eagerly seizing any opportunity to display their latest creations.

Commeter’s inventory listed 158 paintings by Munch which were for sale, and at the beginning of 1905 Munch had shown 75 paintings in Prague. Frames which were labour-intensive to produce could neither be made quickly enough for this enormous number of paintings nor were they economically feasible, particularly for those artists who, like Munch, did not come from affluent backgrounds. As exhibition participation became more frequent and more international, shipping the frames added another financial strain. Heavy frames caused freight costs to skyrocket, whilst gilded surfaces and stucco ornament were prone to damage if not handled properly, often requiring repairs or replacements.

Munch’s altercation with Suhr touches on these problems, which had become an integral part of the daily reality for modern artists by the turn of the 20th century. Many of them eventually reconsidered their frame designs, not only following their changing aesthetic ideas but also pragmatic considerations.

Munch’s ‘horse cure’

Detail of frame from Commeter photos, 1906. Photo: Atelier Schaul, 1906, MM.B.01816G, ©Munchmuseet

However, what sets Munch strikingly apart from most of his contemporaries is his attitude toward the damage inflicted upon his paintings and frames. Not only was he unfazed by the damage Suhr described, but he seemed to embrace it. Munch’s notorious careless attitude towards the condition, storage, and transportation of his artworks was attested to by many of his contemporaries. Rolf Stenersen, Munch’s first biographer, reported anecdotally:

‘It often happened that Munch was quite careless with his paintings. He would even step on them when they were lying on the floor’.[10]

In 1913, Gustav Schiefler received a landscape painting from Munch which had been holed in several places due to inadequate packaging[11]. In response to Schiefler’s complaint, Munch declared:

‘I don’t think that the damage to the picture matters much – although it is unpleasant. By the way, all my paintings are a little holey – it is necessary for it to be a real Munch’. [12]

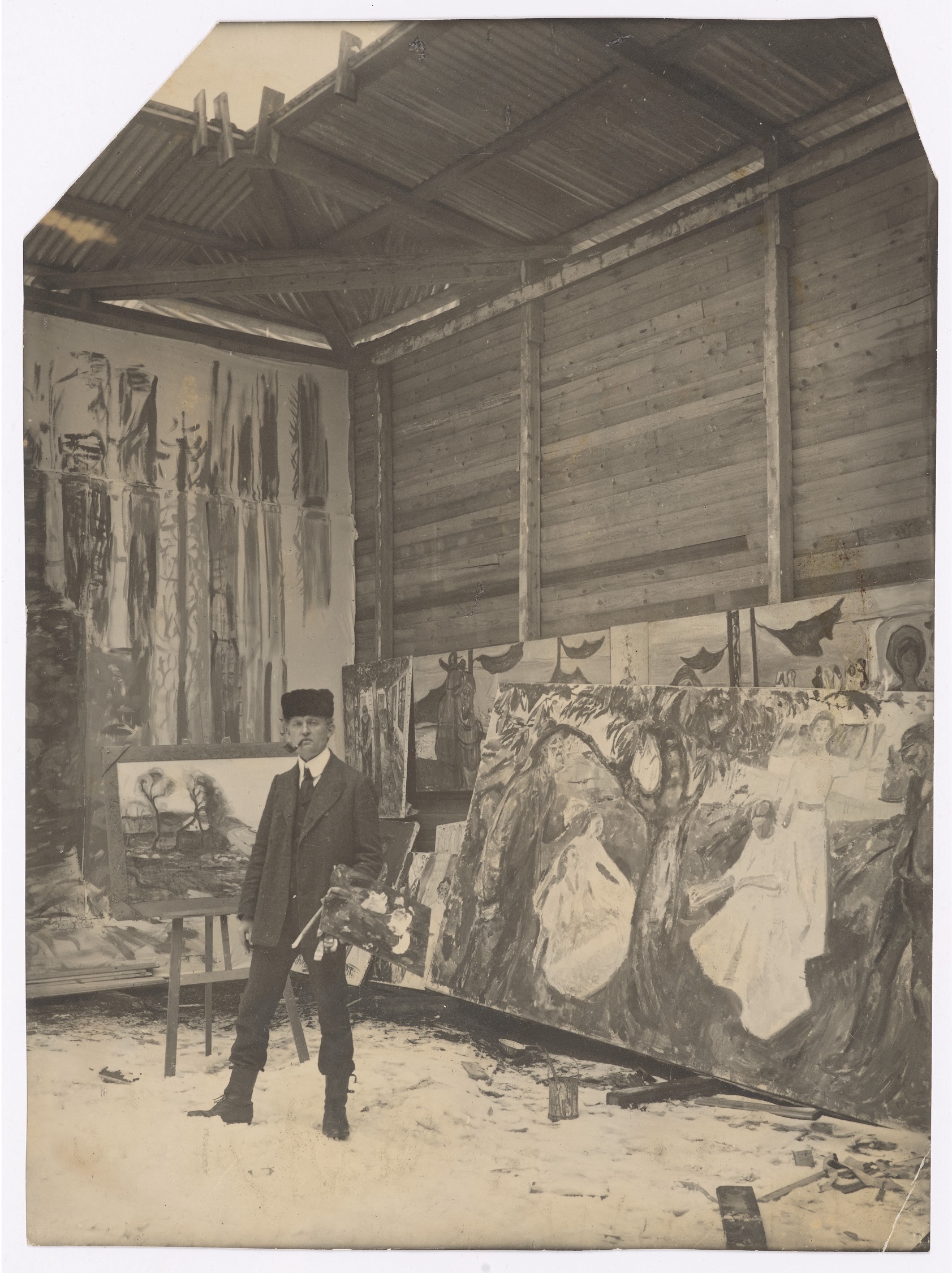

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), in his outdoor studio at Skrubben, Kragerø, 1911-12. Photo: MM.D.02052-03, ©Munchmuseet

The condition of Munch’s paintings and frames, however, was not solely the result of general negligence in handling his works. The damage was often rather the effect of deliberately subjecting his art to the weather. In his open-air studios in Kragerø and Ekely, Munch not only painted but also displayed his pictures, exposing them to sunlight, cold, rain, and even snow for extended periods. Although this so-called ‘horse cure’ had previously been mentioned by Stenersen, it was only in the 1980s that Jan Thurmann-Moe, former head of conservation at the Munch Museum, could definitively prove that Munch deliberately exposed his paintings to the weather to achieve specific natural ageing processes in the surface of the paint layer [13].

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), in his outdoor studio, 1933. Photo: MM.D.01265-03, ©Munchmuseet

The painter explained his intentions as follows:

‘It’s as though my paintings needed a little sun and dirt and rain. The colours often harmonize better this way. My paintings have a tough character when freshly painted. That’s why I’m so afraid that someone will wash my paintings or varnish them. A little dirt and a few holes only clothe them. Only those who paint in brown and yellow and black have such fear of a little dirt’. [14]

Likewise, the painter embraced damage caused by transportation. In one of his diaries, he wrote, that if his

‘…paintings have… sailed around the world in all kinds of miserable, leaky boxes… they will become really good’. [15]

Considering the numerous photographs of framed paintings in Munch’s open-air studios, there is no doubt that some of Munch’s frames inevitably underwent the painter’s ‘horse cure’ as well.

Simple white frames

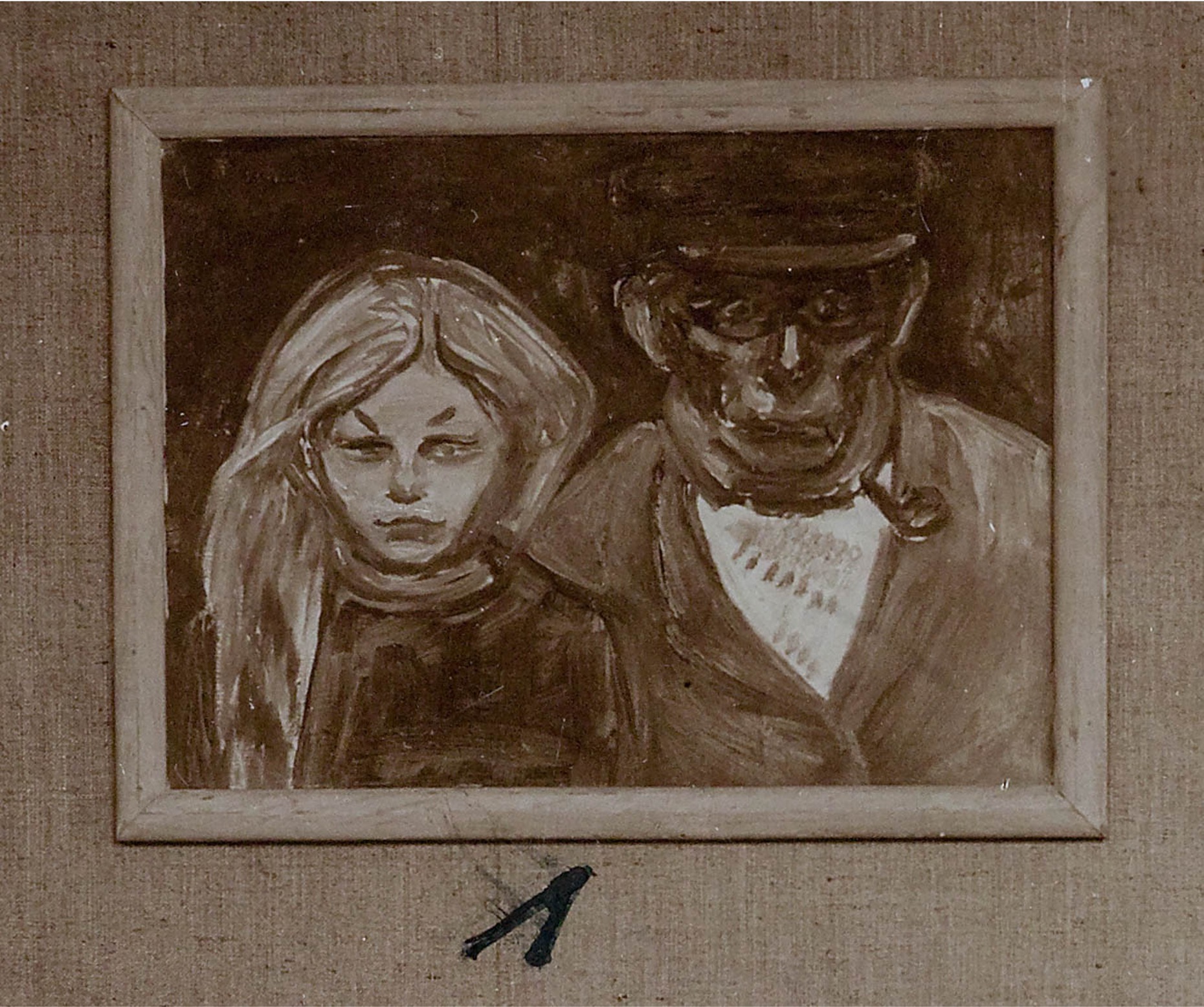

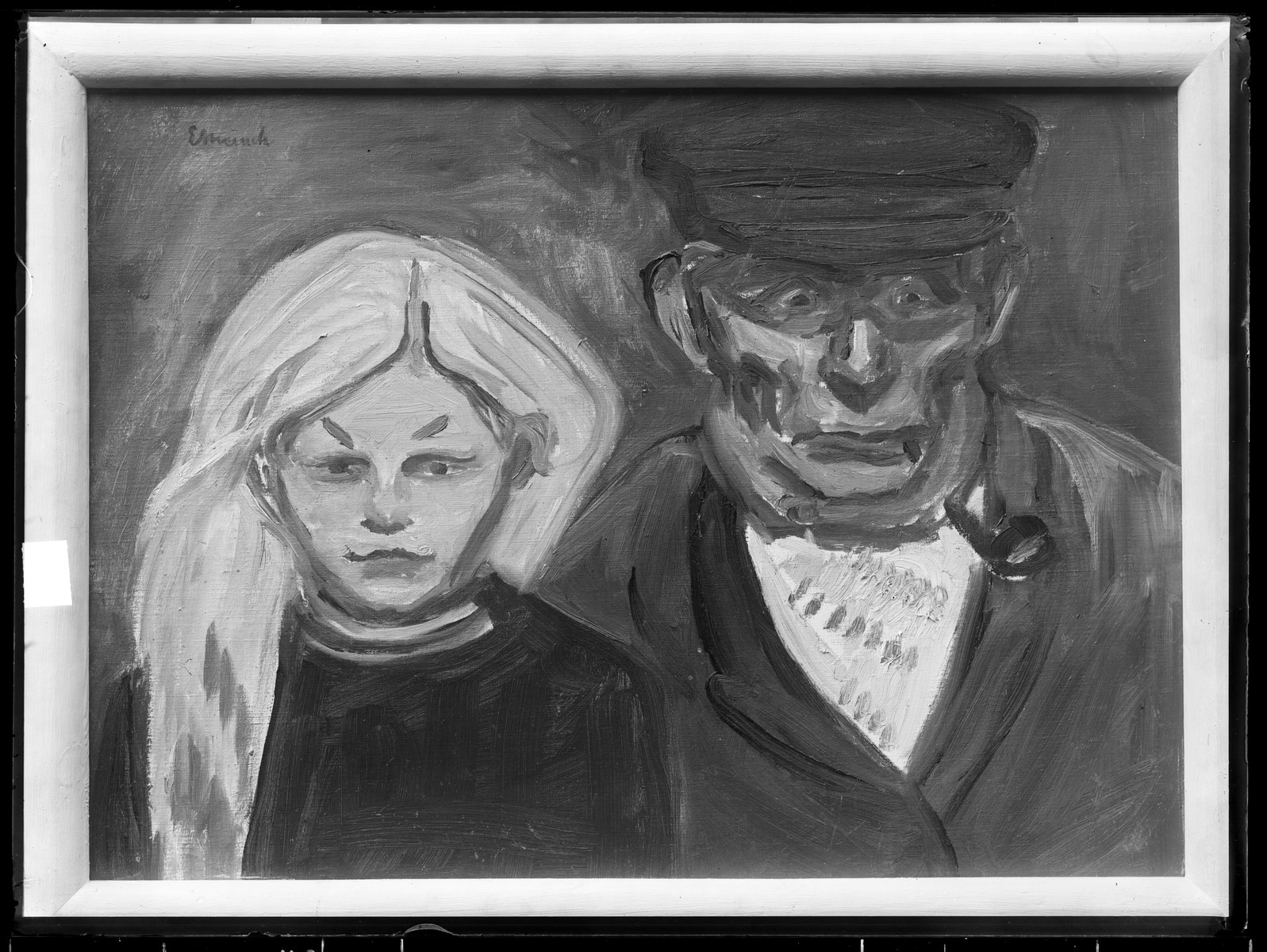

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Old fisherman and his daughter, 1902, detail from photos taken pre-exhibition at Galerie Commeter, Hamburg. Photo: Atelier Schaul, 1906, MM.B.01816aF, ©Munchmuseet

Even though there are no photographs of the final exhibition, we can get some insight into how Munch’s paintings were presented at Commeter. In April 1906, Munch’s close friend Max Linde described the exhibition as the most exquisite Munch exhibition thus far, which he also attributed to the reframing:

‘Commeter’s exhibition rooms are the most beautiful salons one can possibly imagine, and they are perfectly located at the Jungfernsteg. The paintings are hung with dignity. Simple white frames. I have to say, that this made an excellent impression. It is part of the game to respect the external appearance. None of your former exhibitions were prepared as neatly and exquisitely as this one’. [16]

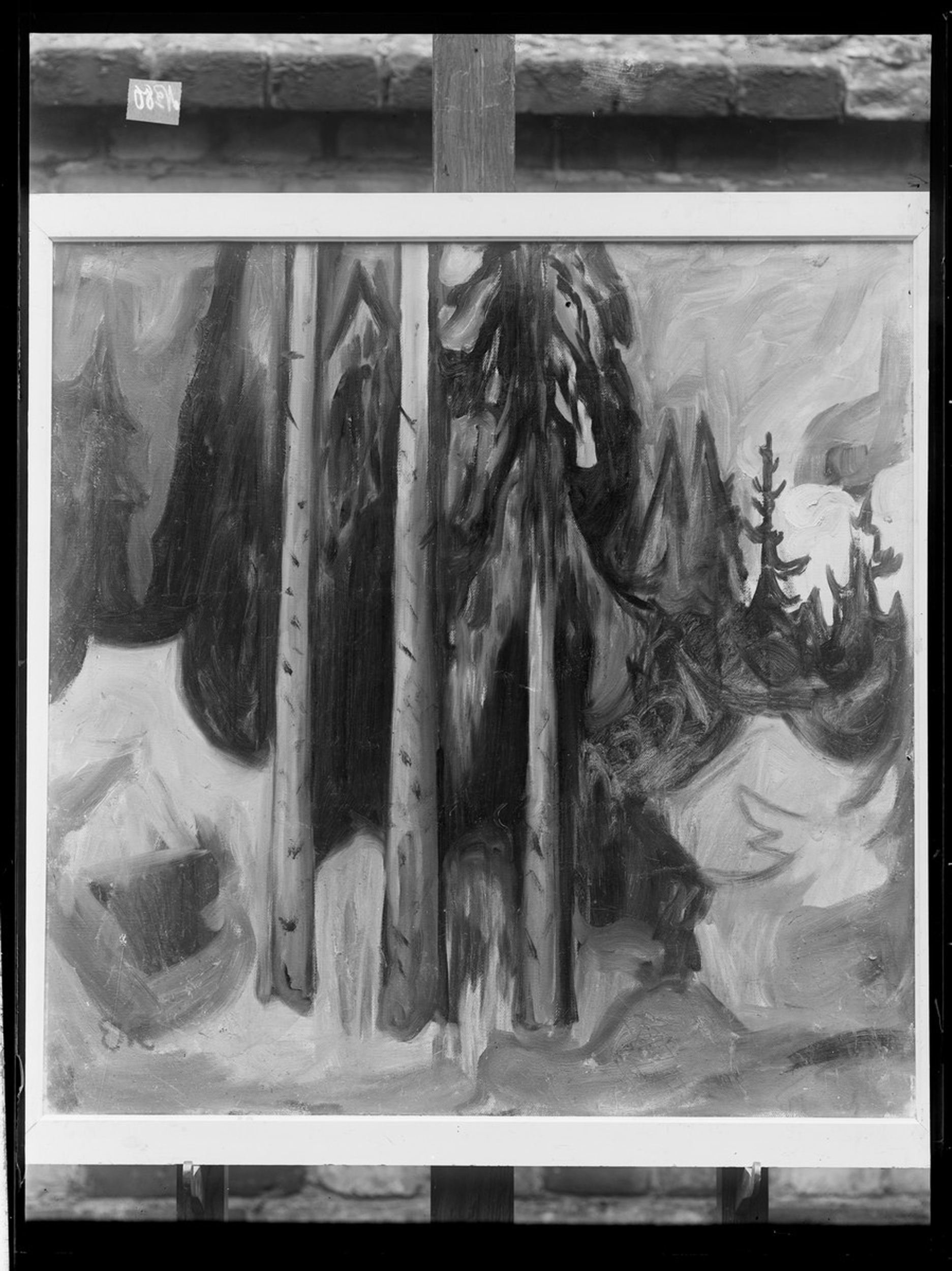

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Forest, 1903, detail from photos taken pre-exhibition at Galerie Commeter, Hamburg. Photo: Atelier Schaul, 1906, ©Munchmuseet

Linde, aware of his friend’s unconventional ways, had repeatedly attempted to exert his influence subtly on the artist. In April 1903, he had already scolded Munch for his careless presentation, saying:

‘A couple of days ago I was in Hamburg to hang the paintings for your exhibition. Unfortunately, the frames were heavily stained and unsightly. You have to put greater stress on decent frames in the future. The spectators think that a well-framed painting is worth more than one which is poorly framed’. [17]

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Old fisherman and his daughter, 1902, photographed in 1914(?). Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Wolfgang Gurlitt-Archiv

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Forest, 1903, photographed in 1914(?). Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Wolfgang Gurlitt-Archiv

In 1914, some of the paintings exhibited at Commeter were photographed again at Kunstsalon Fritz Gurlitt in Berlin (probably on the occasion of the Kollektiv-Ausstellung Edvard Munch), providing a glimpse of the ‘simple white frames’ praised by Linde. A comparison with the 1906 Commeter shots reveals that some of the frames had been repaired and painted white, as Suhr had announced (above, top), while others had been completely reframed with plain white mouldings (above, lower image).

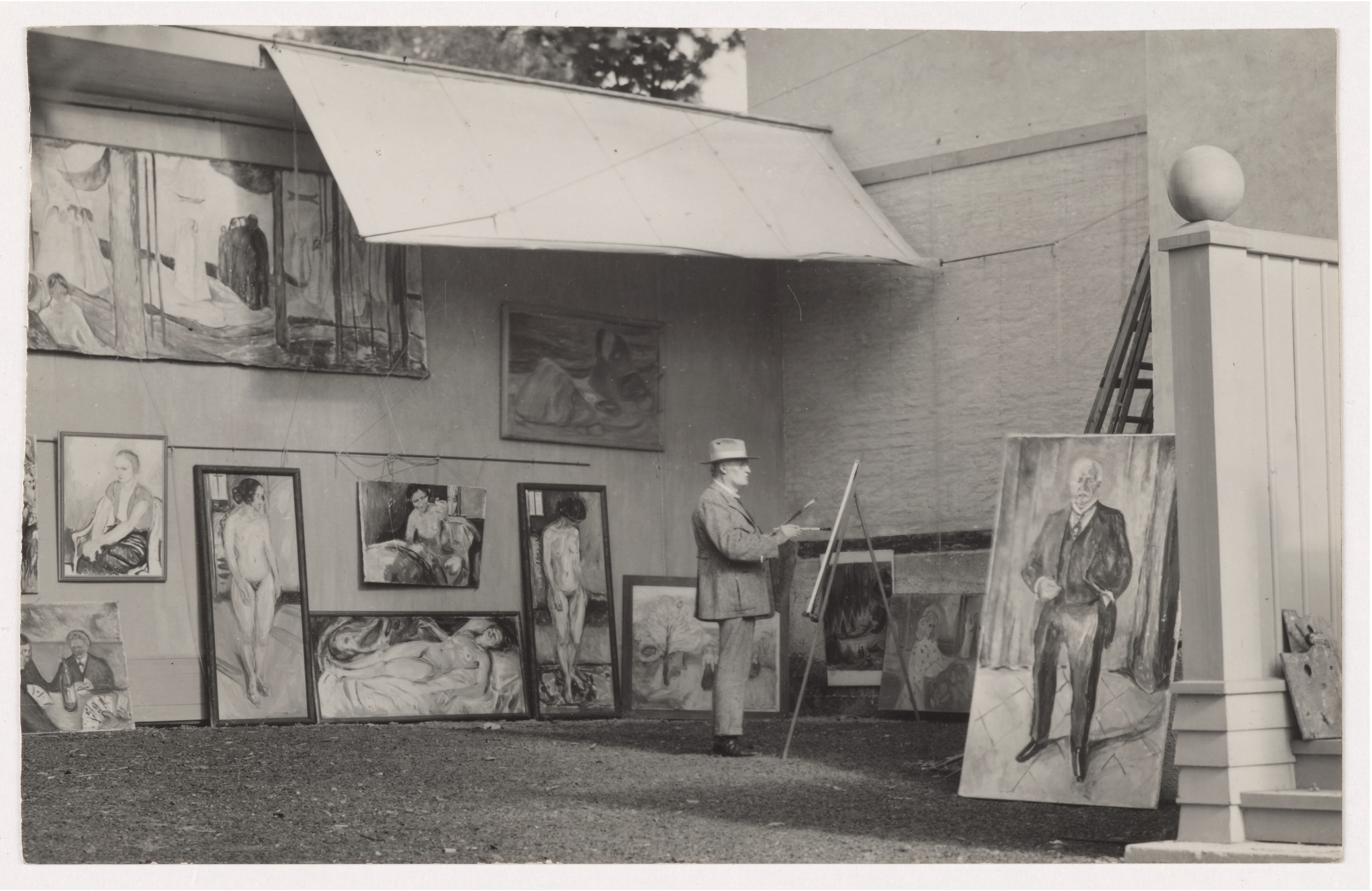

Munch in his studio, 1938. Photo: MM.D.01261-02, ©Munchmuseet

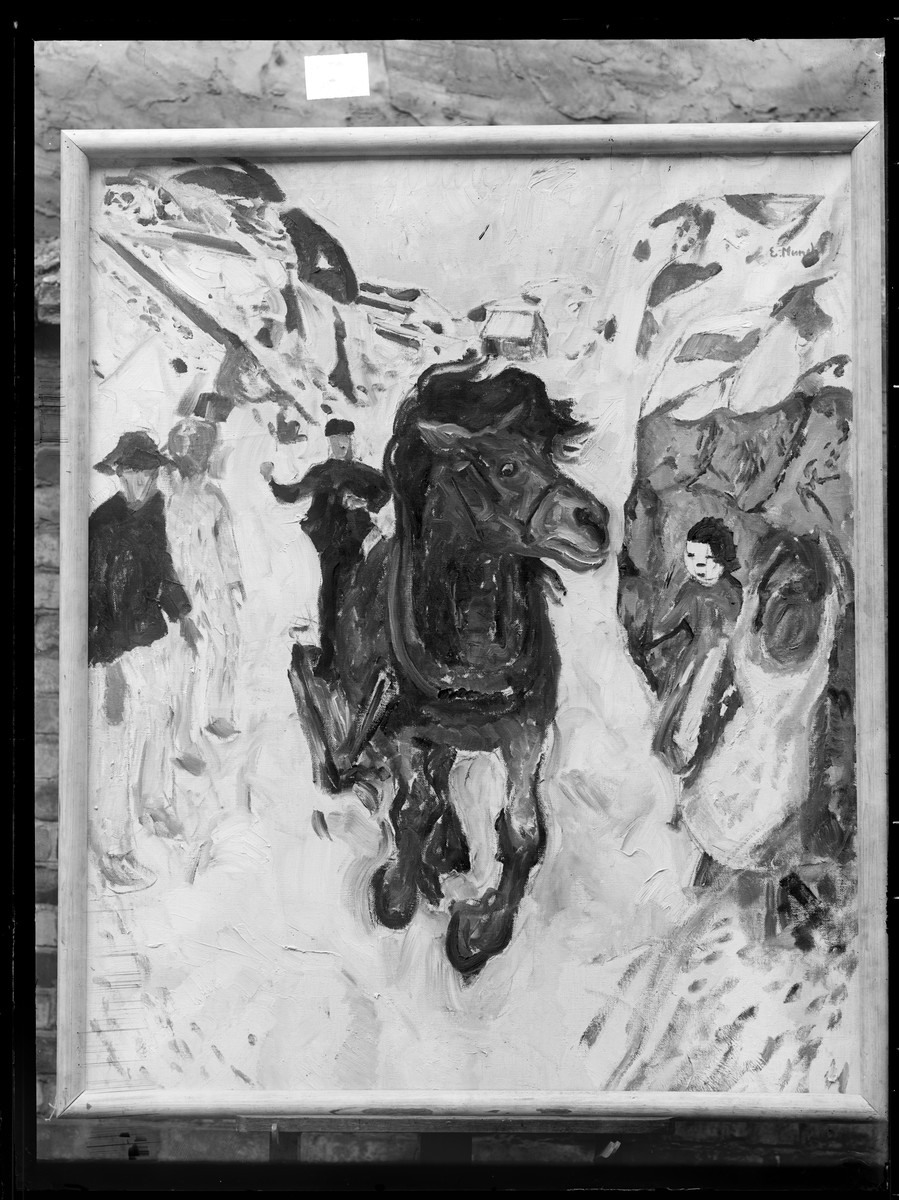

Munch generally had a strong preference for simple and unassuming frames. In photographs of his exhibitions and studios, many of his paintings can be seen in narrow wooden frames, often left unfinished (below) or painted white.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Girls watering flowers, 1904, the frame left in the wood, photographed in 1914(?). Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Wolfgang Gurlitt-Archiv

These frames were not only cost-effective and easy to construct, but they were also comparatively lightweight. The narrow mouldings were easy to carry, as Munch frequently moved his paintings around his studio to experiment with different arrangements. Additionally, the narrow frames allowed Munch to hang his paintings in close-spaced cyclical or frieze-like compositions, whereas a greater width caused them to appear as individual, standalone paintings. Above all, Munch wanted the frames to complement rather than overpower the paintings.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Galloping horses, 19010/12, photographed in 1914(?). Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Wolfgang Gurlitt-Archiv

According to Stenersen, Munch believed that:

‘…[a] good painting can withstand a lot. Only bad paintings must be whole and have noble heavy frames’. He therefore gave them ‘a narrow border, preferably one that is convex and white’.[18]

Franz Marc (1880-1916), The tower of blue horses, 19013/14, photographed before 1930. Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Julius Bard Verlag

The use of narrow convex profiles was a popular choice among numerous modern artists (above).

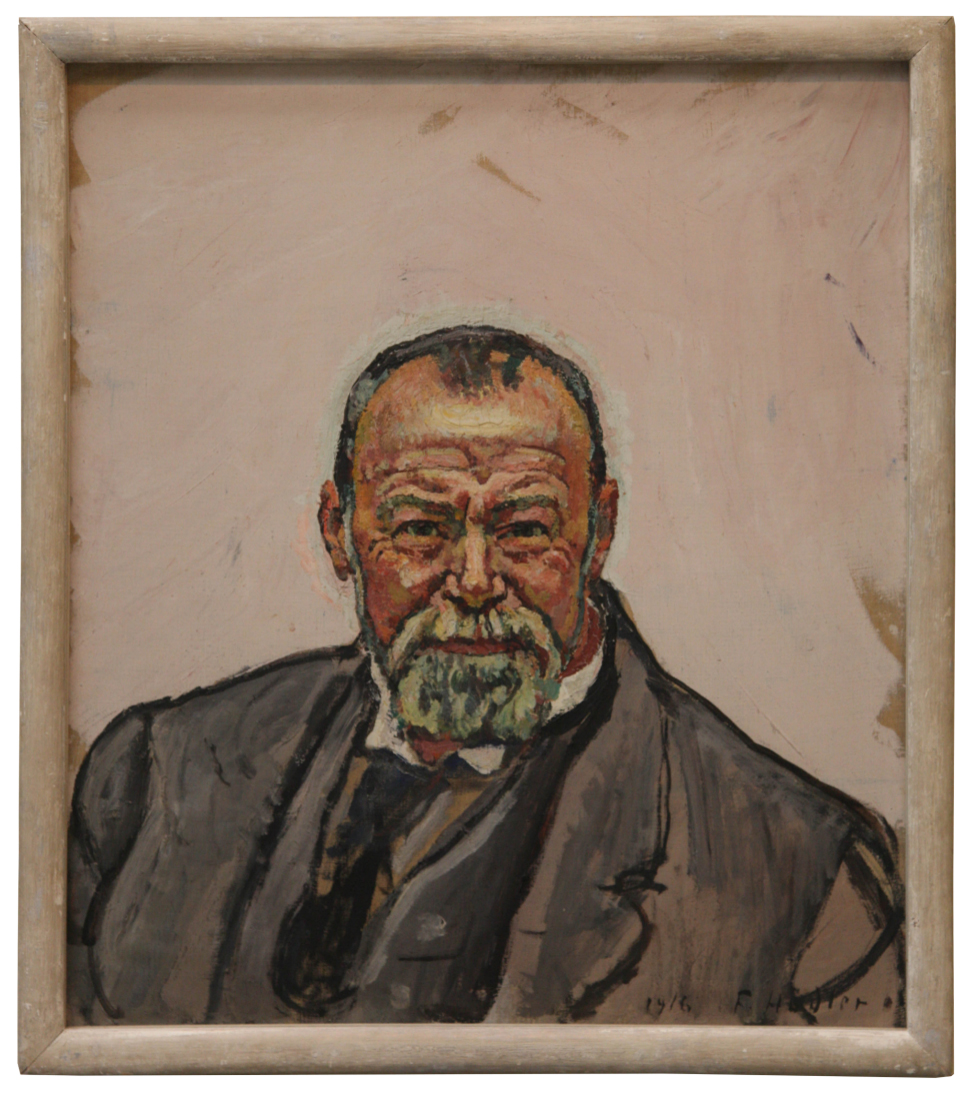

Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918), Self-portrait, 1916, Kunsthaus Zurich

The Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler, for instance, often opted for white mouldings, which can still be seen around many of his paintings today.[19]

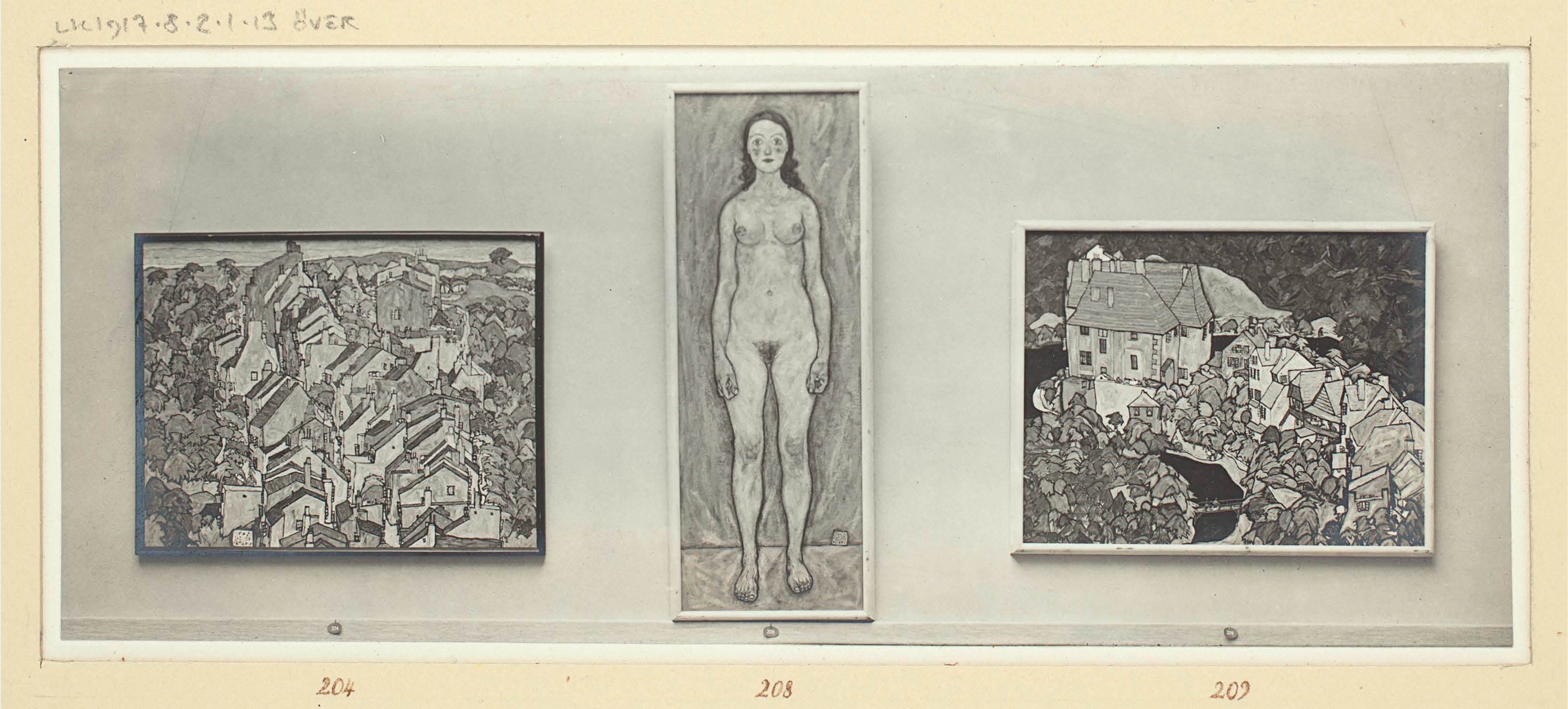

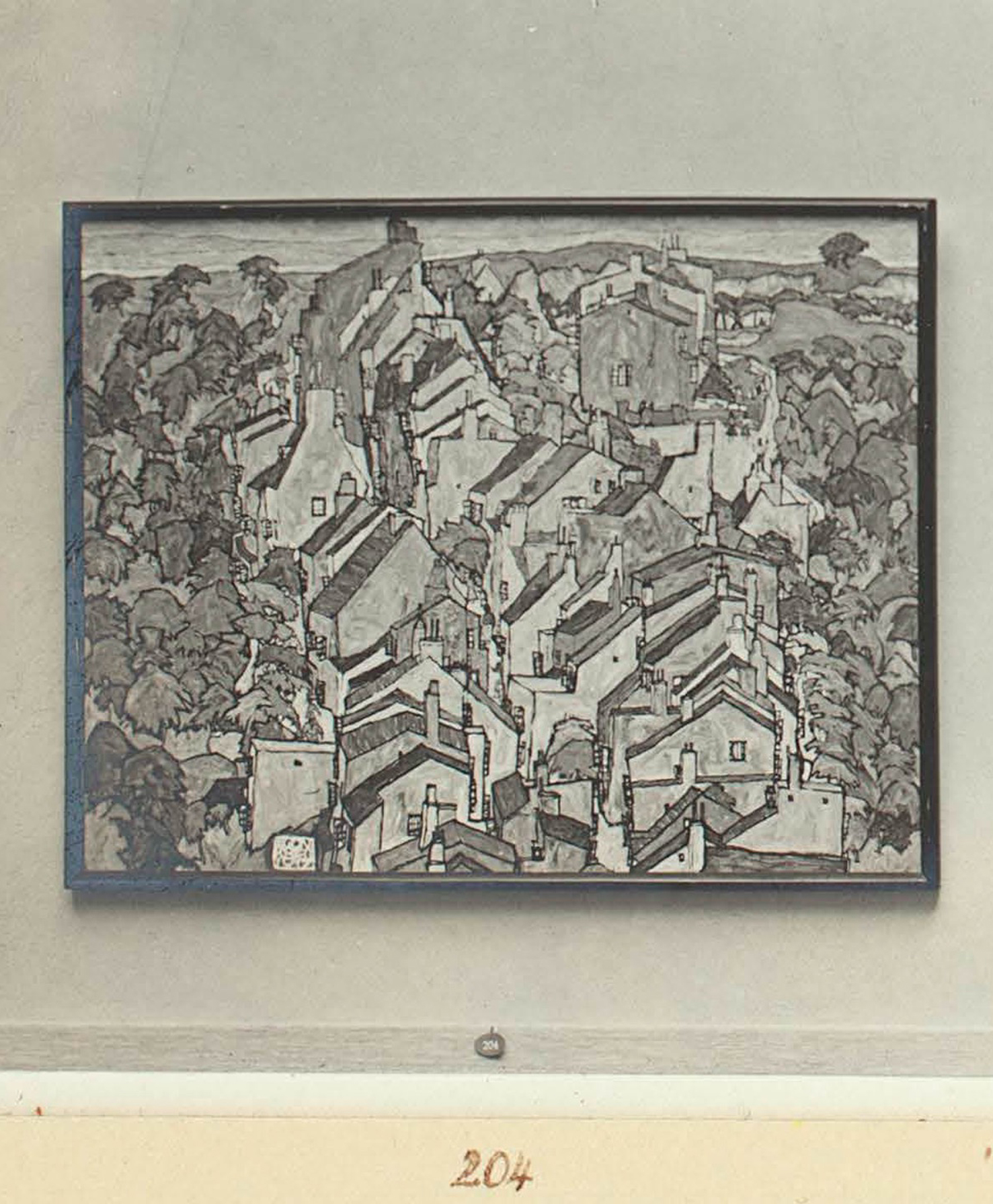

Egon Schiele (1890-1918), paintings at an exhibition in Stockholm, 1917. Photo: Liljevalchs Konsthall Archive, SE/SSA/1265/01, Stockholm City Archive

Egon Schiele (1890-1918), Town among greenery (The old city III), 1917, now Neue Galerie, New York

The Austrians Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele similarly preferred a particular profile known as ‘Hoffmannleiste’, which was favoured by artists associated with the Viennese Secessionist movement and was also sometimes painted white. Their shared preference for these profiles highlights a broader trend towards more functional designs within artistic circles of the era. The distinct lack of decoration in these frames reflects contemporary discussions of ‘material truth’ and ornament which unfolded in the second half of the 19th century. With the rise of industrially-produced surrogate materials, plaster ornaments were increasingly regarded as dishonest, compared with those painstakingly carved from wood. At the same time, the proliferation of historically-inspired styles and the prevalence of frames with cheaply-made plaster ornament led to oversaturation, and ultimately to the rejection of excessive ornamentation amongst many modern artists. Instead, they preferred functional designs with plain surfaces, emphasizing the use of ‘honest’ materials.

Examples of reframing during Munch’s lifetime

Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm, 1908

Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm, 1908

Thielska Galleriet, date unknown

It appears that the replacement of Munch’s frames during his lifetime was more of a common occurrence than an exception. This was largely due to the fact that many of Munch’s frames did not align with prevalent contemporary tastes or were simply too damaged. The Swedish collector Ernest Thiel, for example, had some of the white frames removed and others refinished in consultation with Munch, because they did not harmonize with the rest of the furniture in his rooms [20]. The gilt frames chosen by Thiel can still be seen in the Thielska Gallery today.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Puberty, 1894, Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo

Similarly, the National Gallery in Oslo opted for heavy, ornate gilt frames for its Munch paintings to match the museum’s prestigious surroundings.

Metabolism – from idea to finished frame

There is, however, a small number of Munch’s frames which have managed to survive to this day, thanks to their distinctive artistic design.

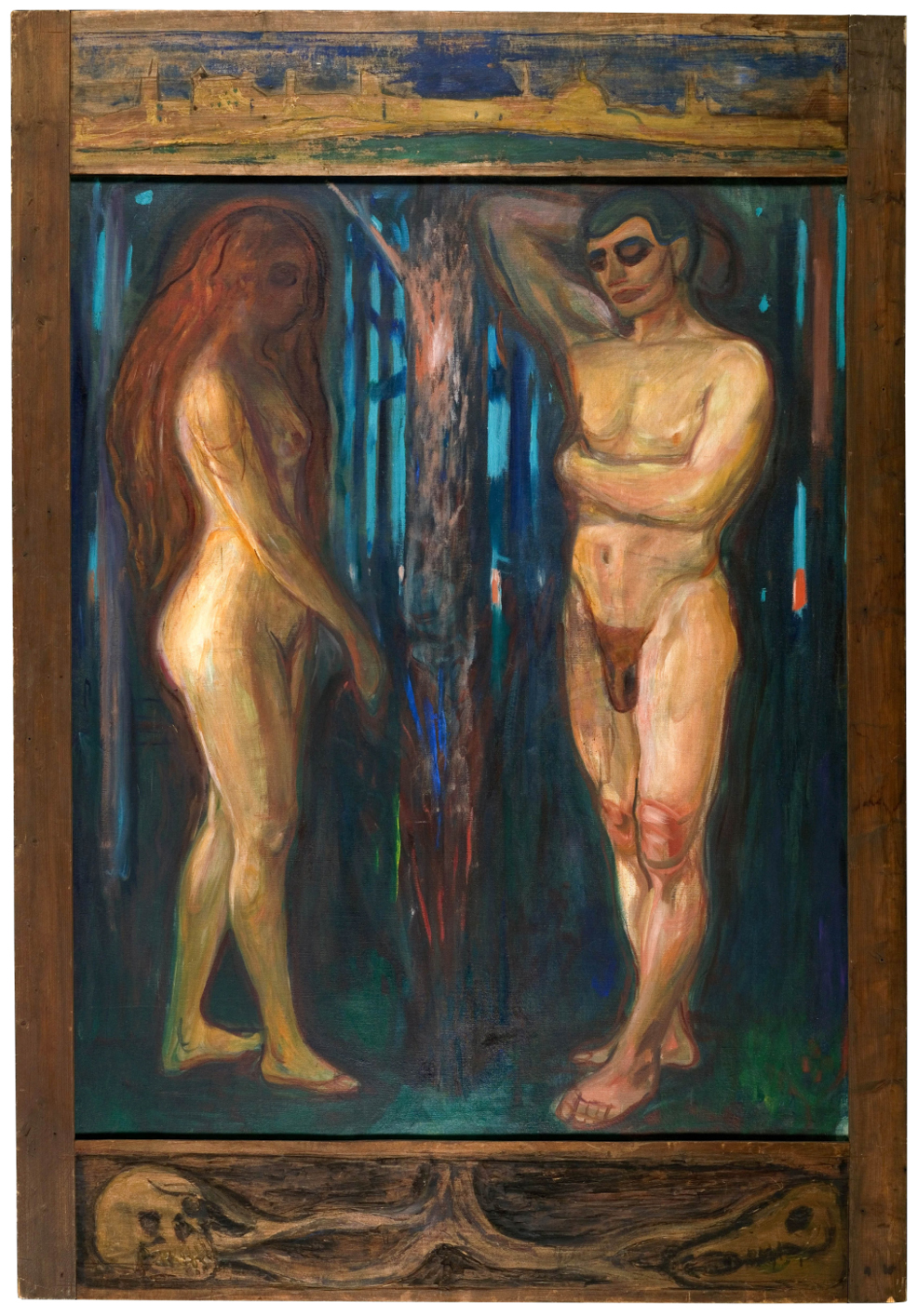

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Metabolism, 1898-99, Munchmuseet, Oslo. Photo: MM.M.00419, ©Munchmuseet

One notable example surrounds Munch’s Metabolism from 1899. The frame goes beyond merely complementing the colours of the painting, as seen, for example, in frames by artists like Georges Seurat or Vincent van Gogh. Instead, it incorporates roughly executed and partially painted carvings which expand upon the composition of the painting, contributing significantly to its overall meaning.

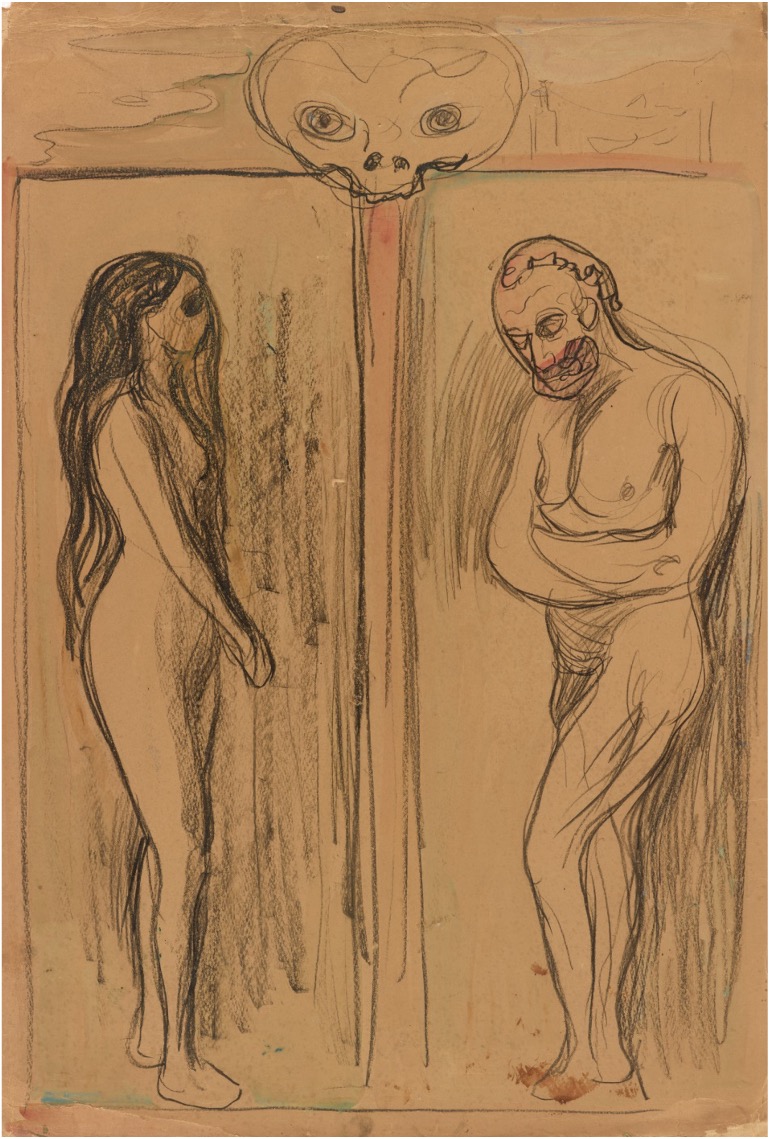

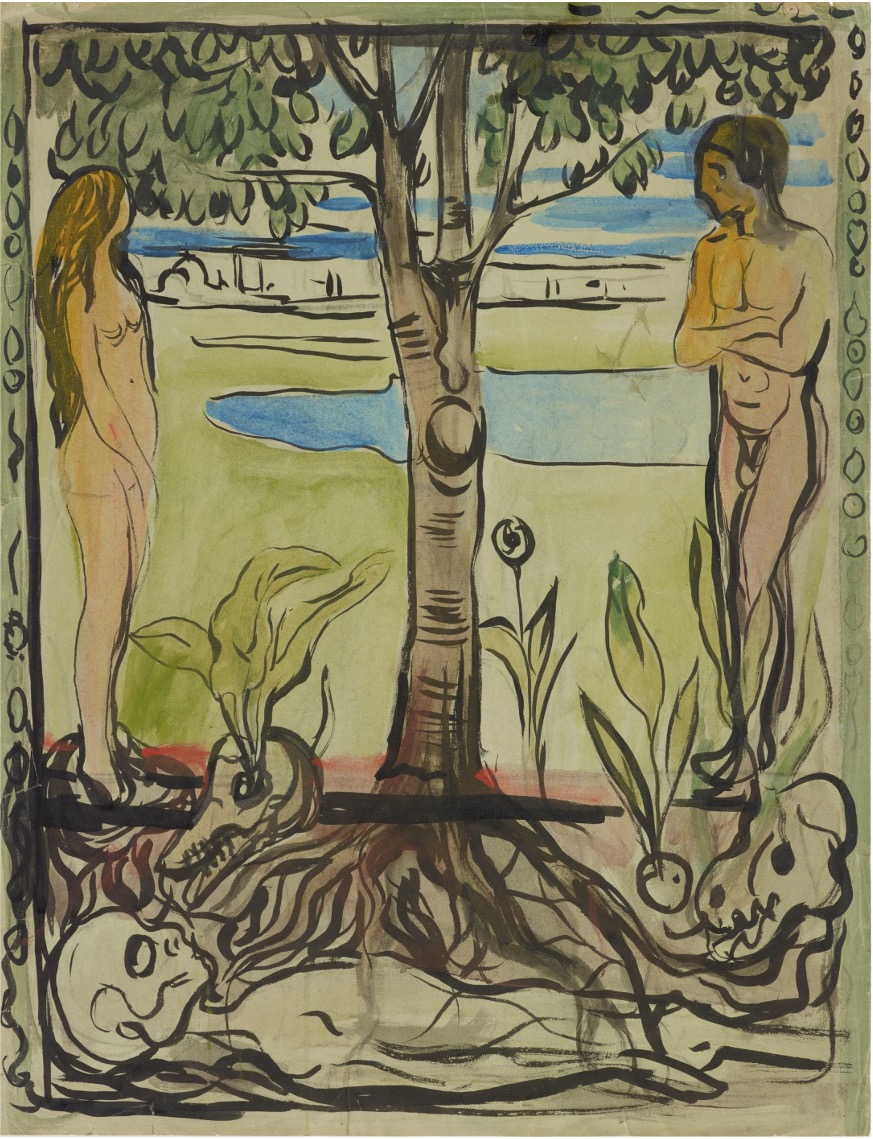

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Metabolism,1898, Munchmuseet, Oslo. Photo: Photo: MM.T.00413, ©Munchmuseet

Munch experimented with this particular frame in various sketches. At one point, he envisioned the two figures in a diptych, with a grotesque head serving as the central crest, but ultimately decided to separate the couple on either side of a tree.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Metabolism,1898, Munchmuseet, Oslo. Photo: Photo: MM.T.02447, ©Munchmuseet

Additionally, he introduced a lower ‘predella panel’, like those found in altarpieces. The reclining corpse entwined with roots is evocative of the body of the dead Christ, traditionally often depicted in the predella. In the final frame design, however, this idea was further condensed to a human skull. The city, previously only hinted at in the background of the drawing, was reimagined as a carved silhouette on the upper moulding of the frame. By incorporating the cityscape and the skull into the frame, Munch achieved a reduction in visual elements within the painting, allowing for a heightened focus on the two central human figures.

Ludwig von Hofmann (1861-1945), Largo (Sonnenuntergang), c.1898, o/c, 74 x 119.5 cm., Belvedere, Vienna

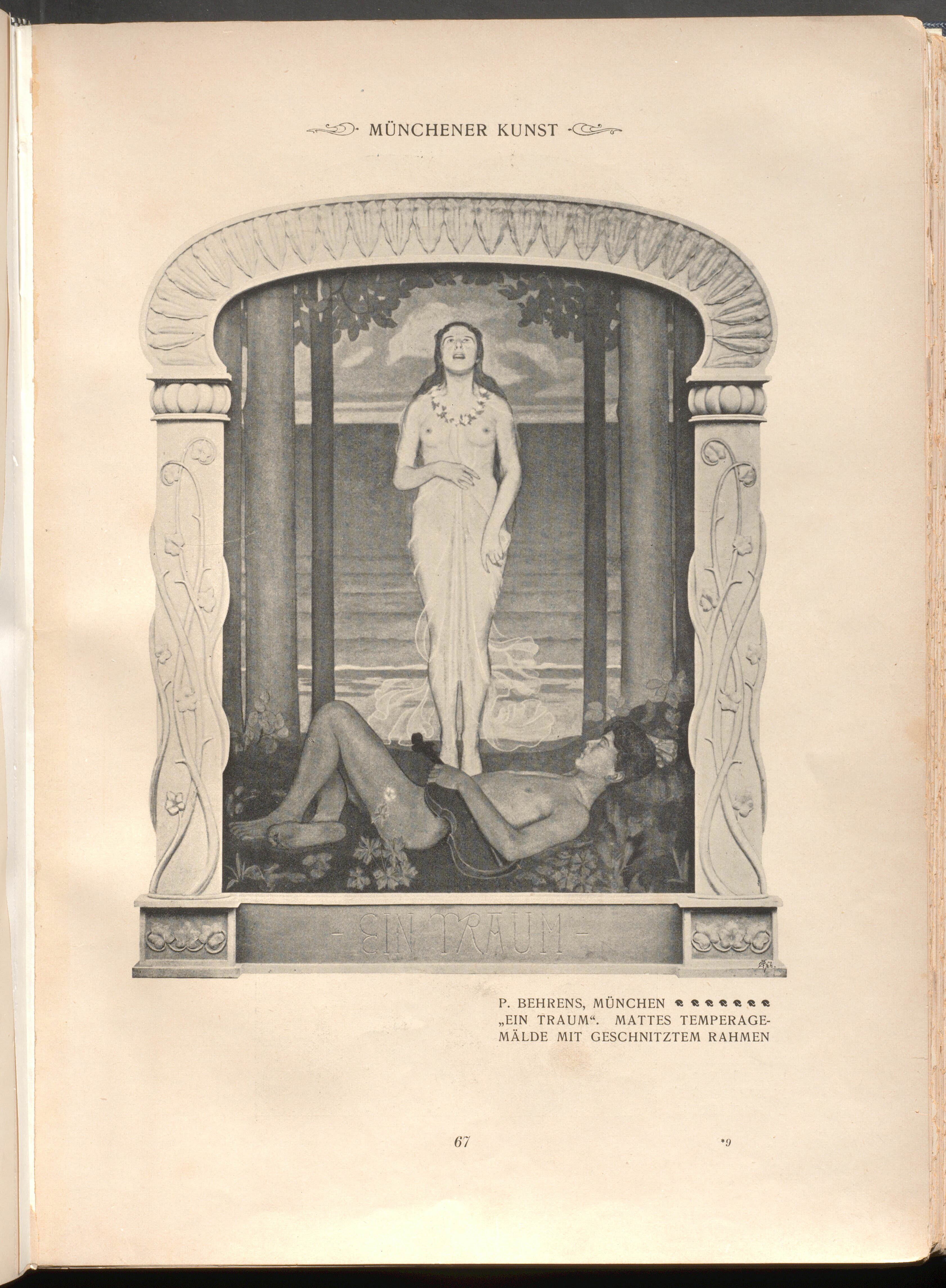

Peter Behrens (1868-1940), Ein Traum, c.1899, illustrated Dekorative Kunst, 3, 1899, p. 67

Munch’s Metabolism reflects the Art Nouveau and Symbolist zeitgeist, where artists often added possible interpretations and attributive references to the frame [21]. However, most of these highly individualistic and elaborate frames were often one-of-a-kind pieces, which were not designed for large numbers of paintings.

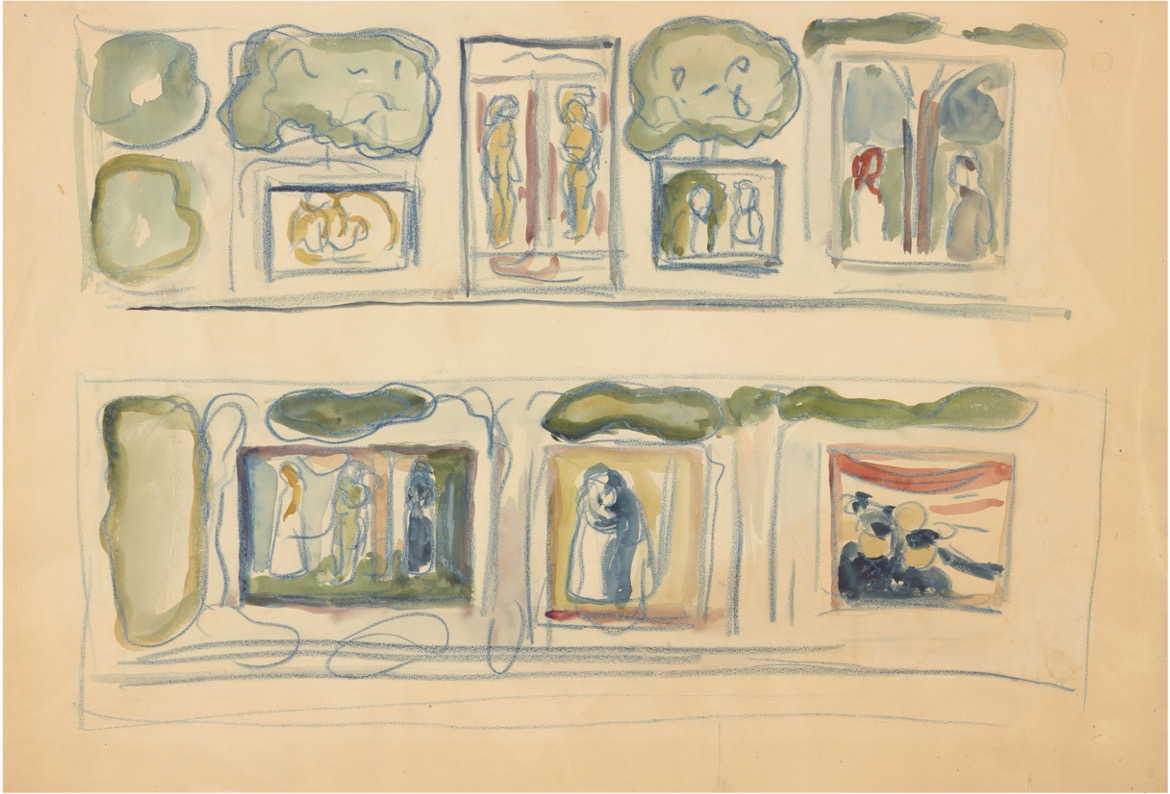

The Life Frieze, displayed at the exhibition of Munch’s work, 1903, Kunsthandlung Beyer & Sohn, Leipzig. Photo: MM.B.1102F, ©Munchmuseet

Metabolism eventually took a significant position in the Life Frieze, where it was further emphasized by its remarkable frame.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), sketch of the Life Frieze, 1917-24, watercolour on paper, MM.T.02411, ©Munchmuseet

In later sketches, Munch experimented with the presentation of his Life Frieze, extending the pictorial object beyond the frame onto the wall itself, reflecting the tendencies of Art Nouveau to synthesize separate elements into a coherent aesthetic.

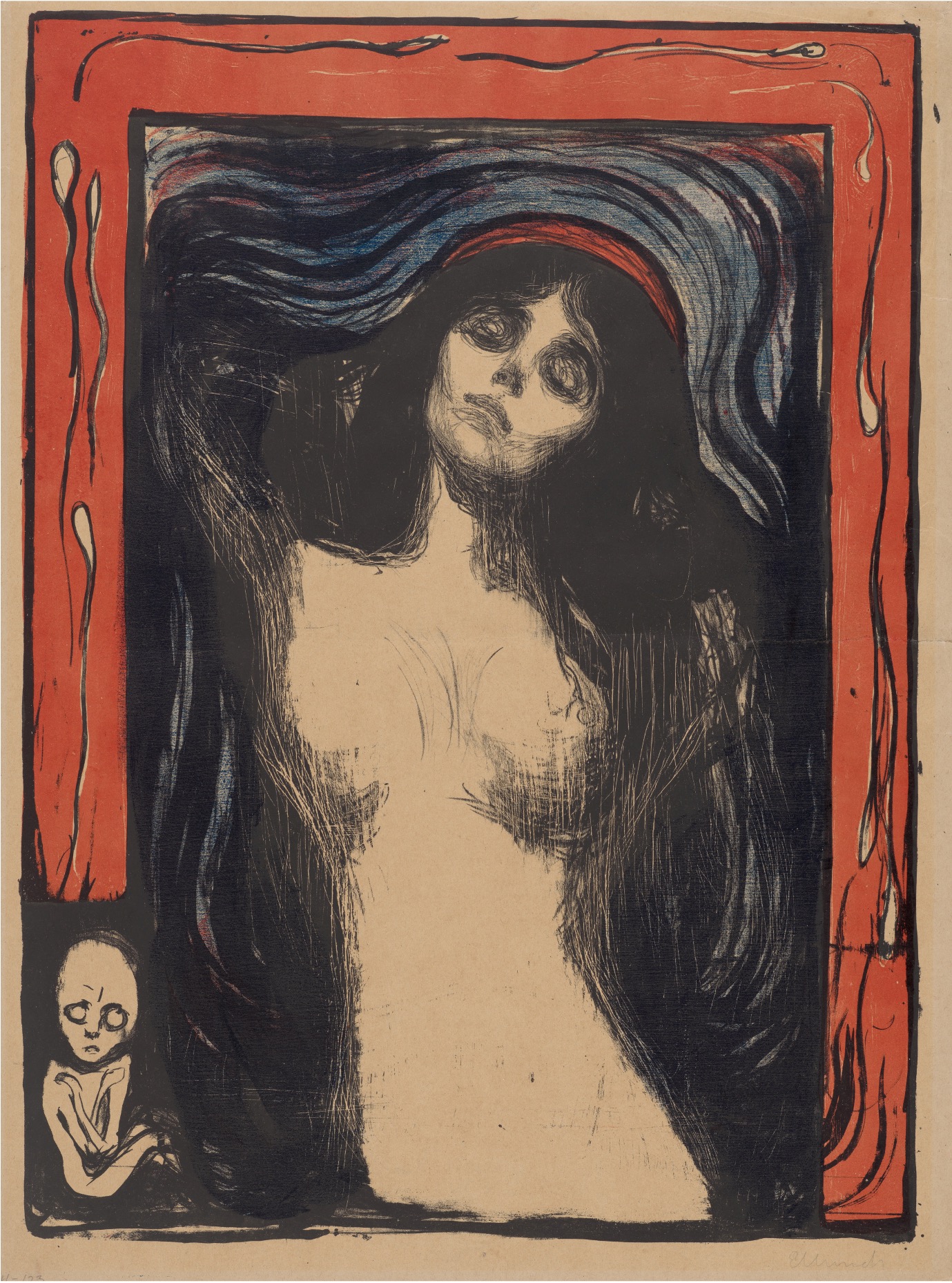

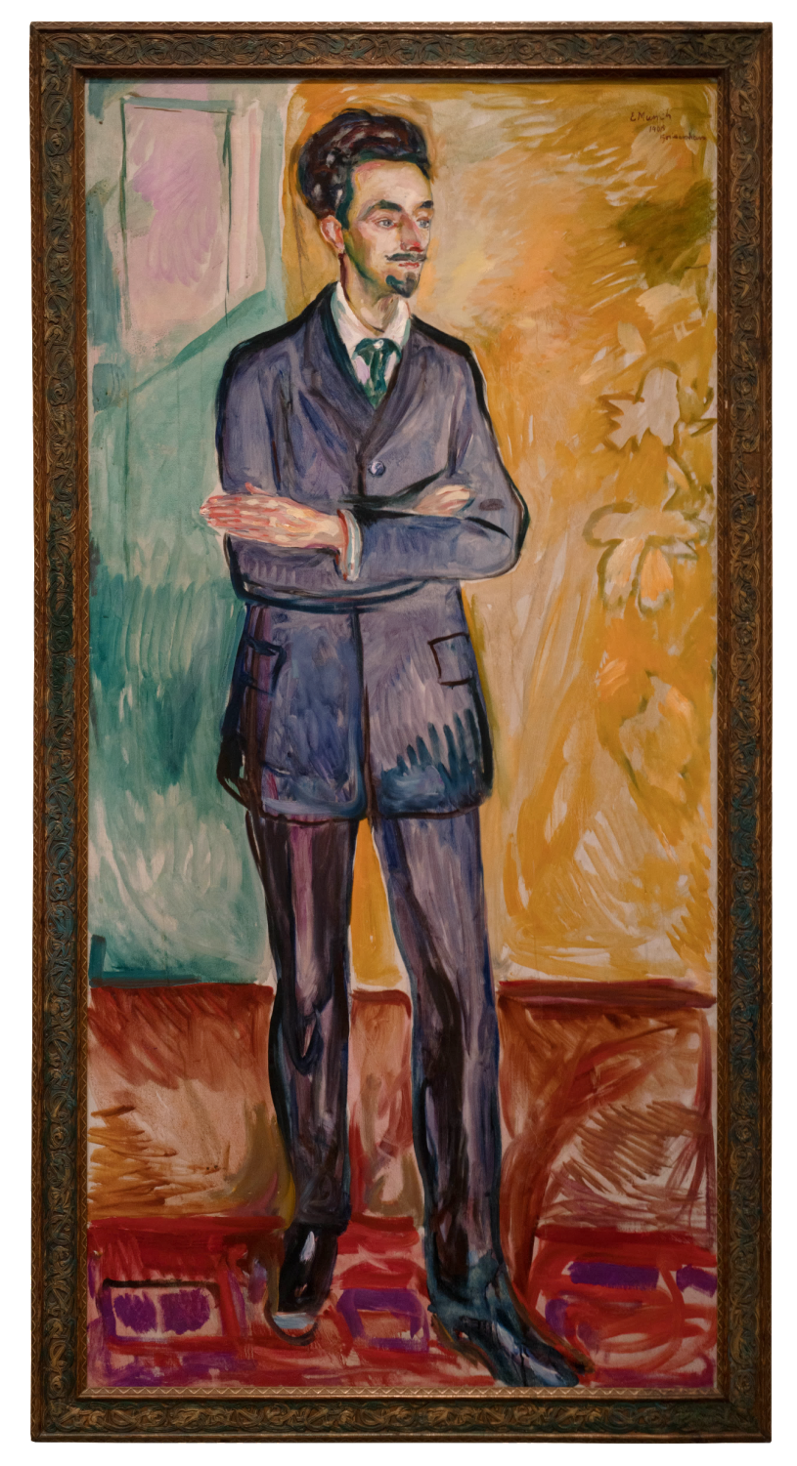

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Madonna, 1895/1902, coloured lithograph, MM.G.00194-19, ©Munchmuseet

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Portrait of August Strindberg, 1896, lithograph, MM.G.00219a-04, ©Munchmuseet

The addition of supplementary emblems to the frame can also be found in Munch’s graphic works, such as the lithographs Madonna and the Portrait of August Strindberg. Munch incorporates complementary motifs into the borders of both images – sperm and an embryo, and a naked female figure respectively – adding another layer of meaning to each image. Whether these drawings were intended as models for actual frames remains unknown [22].

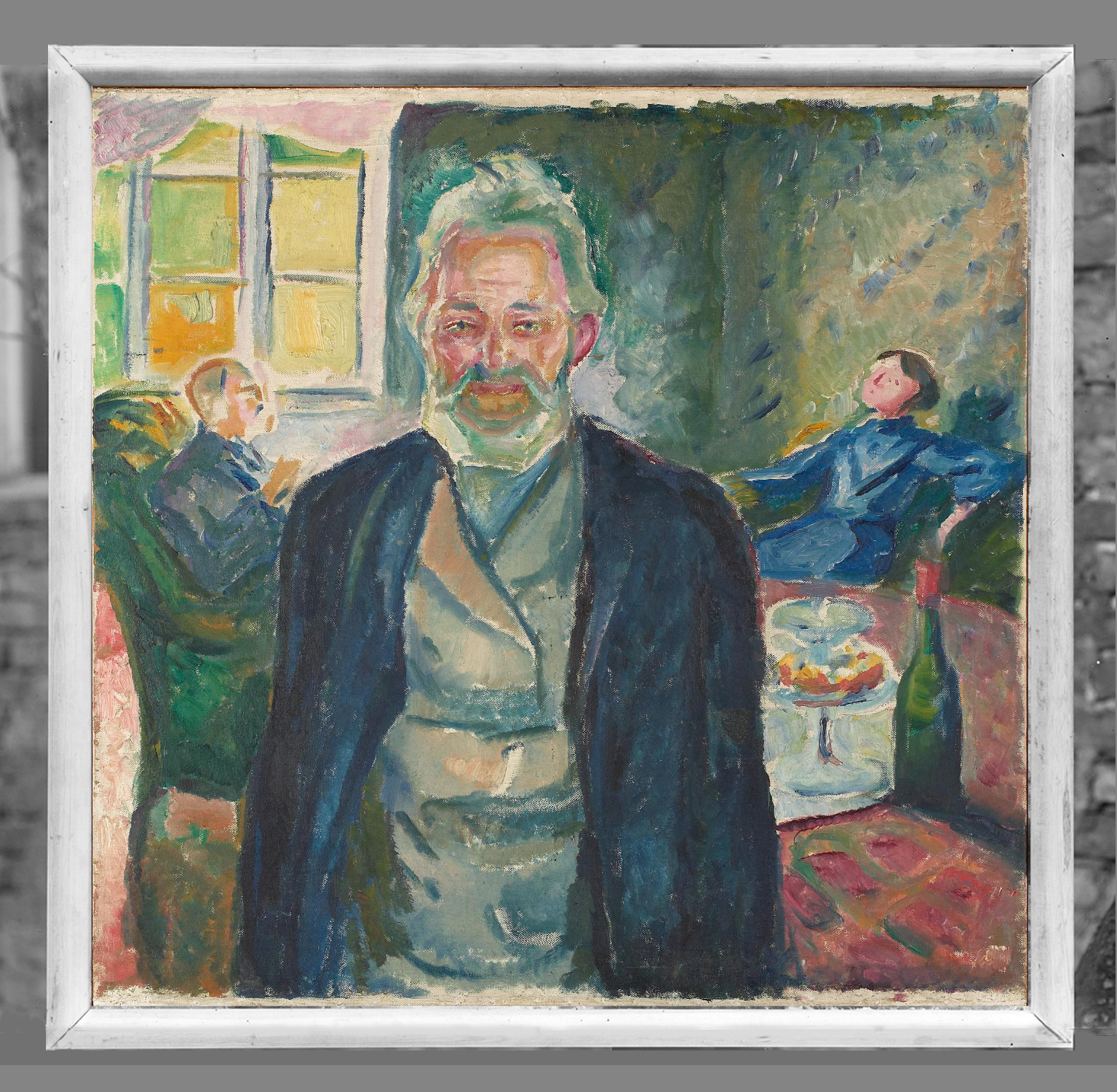

Overpainted frames

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Portrait of Helge Rode, 1908, and detail of frame, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

A moveable frame which was finished by Munch himself surrounds his 1908 portrait of Helge Rode. The painting is set in a flat, wide moulding decorated with Celtic-inspired zoömorphic ornamentation, a popular motif in Nordic countries at the time [23]. Munch colour-co-ordinated the commercially-produced frame with the painting by applying swift brushstrokes of blue and green paint over the mass-produced ornament.

In 1909 the portrait was exhibited in a narrow white frame, while by 1912 it already had its current frame [24].

A photograph taken at Gurlitt in 1914 suggests that the frame had been painted by that point – although it is noticeably smaller than its current size, covering much more of the painting than is visible today. An archival photograph from 1969 shows the frame in its original, smaller format.

Munch, Portrait of Helge Rode, detail of cut on frame

A cut on the top right corner is proof of its later enlargement. Interestingly, the frame is now displayed rotated 180 degrees.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Daniel Jacobsen, 1908/09, and detail of frame, photographed 1914 (?); exh. 1912 at the Sonderbund in the same frame. Photo: Photo: Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Wolfgang Gurlitt-Archiv

It was not the only frame to have been touched up by the artist. Photographs from the Internationale Kunstausstellung des Sonderbundes westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler 1912 and by the Kunstsalon Fritz Gurlitt in 1914 both depict frames which were similarly painted over [25]. Whilst the painter generally left simpler frame designs untouched, he seemed to feel the need to adapt more ‘conventional’ examples to his preferences by covering them with visible brushstrokes.

Overpainting gilt frames was not entirely uncommon during that period. For example, James McNeill Whistler painted patterns to the surfaces of his gilded frames to reflect the dominant colours of his paintings. Additionally, many French art dealers preferred using colour-washed or toned 18th century frames to present Impressionist paintings instead of the artists’ original designs [26].

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), Der Maler (Self-portrait), 1920, Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe

This practice may have inspired the German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, who painted over some of his own bronze frame designs in order to marry them to his paintings. While Munch’s influence on Kirchner and other artists from Die Brücke is well-documented, it remains unclear whether Munch’s frames specifically served as inspiration for Kirchner’s treatment of his own frames.[27]

Attic finds: original Munch frames in Åsgårdstrand

Munch’s summer cottage at Åsgårdstrand, 1889. Photo: MM.D.01362-01, ©Munchmuseet

Munch’s artistic legacy left an extraordinary imprint on posterity. Upon his death in 1944, the Oslo Municipality inherited over 1,100 paintings and tens of thousands of prints, drawings, and sketches, which were scattered all over his home in Ekely, where the artist had lived and worked since 1916. As WWII progressed Munch seemed to have taken precautionary measures to protect his artworks. Some of his paintings were taken off the stretchers and rolled up in the basement; many remained in this damp environment and showed signs of decay and mould [28]. The frames probably shared a similar fate and were not deemed worthy of restoration, assuming that they hadn’t been repurposed as firewood during the War.

Frames found in the attic at Åsgårdstrand. Photos: Roger Berg, Munch hus, MUH.00277 & MUH.00272

However, some original frames remained intact at Munch’s summer home in Åsgårdstrand, having survived decades without the attention of researchers or art historians.

Gilded frames as a symbol for the commodification of art

Munch’s frame designs were not solely driven by aesthetic or practical considerations but were also a manifestation of his Bohemian and non-conformist ideas. They served as a critical response to institutionalized and commercialized exhibition practices and bourgeois art consumption.

In 1884 Munch received a travel grant which took him to Antwerp and Paris, where he attended the World Exhibition and visited the Louvre and the Salon. Reflecting on his experience, he wrote:

‘Seven years ago, I came to Paris for the first time and had a burning desire to visit the Salon. I expected to be moved, but instead, I was overcome by the urge to vomit. The old paintings of Bouguereau took centre stage. The bourgeoisie was as much interested in them as if they were labels on cigarette packets’. [29]

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905), La première discorde (Cain and Abel), 1861, top right, 1861 exhibition in the Palais de l’Industrie. Photo: Pierre-Ambroise Richebourg, BnF, Paris

At the time Bouguereau was considered one of the greatest academic painters. His works were highly sought-after and commanded high prices. As a matter of fact, Bouguereau himself admitted in 1891 that the direction of his later work was largely influenced by public taste, in order to sell his paintings [30].

In his writings, Munch expressed strong disapproval of the increasing commodification of art. In this context, he repeatedly associated facile, marketable art and bourgeois taste with gilt frames. In several written notes, he distanced himself and his art from

‘…easily marketable standard pictures in gold frames’ [31]

‘…intended for a bourgeois audience [32], as well as from painters

‘…who believe that small-format pictures in wide gold frames are the best currency’. [33]

The connection between gilded frames and mainstream, commercialized art was established through the framing conventions of the big annual Salons, where gilt frames were mandatory throughout much of the 19th century. The bourgeoisie and nouveaux riches sought to emulate the opulent exhibition frames on a smaller scale in their own homes.

Pissarro (1830-1903), In the garden at Pontoise: Young woman washing dishes, 1882, o/c, 81.9 x 65.3 cm., Fitzwilliam Museum

The French Impressionists were some of the first to dismiss gilt frames almost completely, opting instead for comparatively plain frames, often in unconventional colours, including white.[34] As early as 1881 their choice of frame was viewed as a deliberate anti-academic and rebellious statement, as the art critic Jules Clarité noted:

‘The greatest originality of these revolutionaries lies in the white frames of their works. The gold frames were left to the old painters, the chewing tobacco juice smears, and the opponents of light-coloured paintings’. [35]

Munch’s frames emerged from this way of thinking, where ornate gilded frames became associated with the established, conservative cultural industry and the bourgeoisie, from whom avant-garde artists sought to distance themselves. Their colour, simplicity, and not least their damaged condition, were opposed to academic ideals and bourgeois taste, perfectly aligning with the radical spirit of his paintings.

*******************************************

Marei Alexandra Döhring is a Ph.D. fellow at the University of Vienna, specializing in early 20th-century artist frames. In her master’s thesis, she explored the frames created by the artist group Die Brücke, focusing on Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Emil Nolde. Whilst working for a German frame workshop, she conducted in-depth research on Edvard Munch for the reframing project of the new Munch Museum in Oslo, which opened to the public in the autumn of 2021.

*******************************************

Edvard Munch (1863-1944), Old man in an interior, 1912/13, Munchmuseet, Oslo, montaged with its original frame. Photo of frame: 1914

*******************************************

[1] Munchmuseet, MM N 2714, draft letter to an unknown person, 1906 (all translations are by the author if not stated otherwise)

[2] Munchmuseet, MM N 2471, draft letter to Gustav Schiefler, 1906. Munch is also alluding to the ‘First Moroccan Crisis’ or the ‘Tangier Crisis’ which took place between March 1905 and May 1906, and in which Germany was challenging France’s growing control over Morocco

[3] Munchmuseet, MM K 3822, letter from Wilhelm Suhr to Munch, 04.04.1905

[4] Munchmuseet, MM K 3836, letter from Wilhelm Suhr to Munch, 21.02.1906

[5] Munchmuseet, MM K 3835, letter from Wilhelm Suhr to Munch, 15.02.1906

[6] Munchmuseet, MM K 3836, letter from Wilhelm Suhr to Munch, 21.02.1906

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ambroise Vollard, En écoutant Cézanne, Degas, Renoir, 1938, ed. 1985, pp. 118-19 (Internet Archive). See the relevant extract from the book here, in ‘What artists, critics & collectors say about frames: Part 3’

[9] Munchmuseet, MM K 3837, letter from Wilhelm Suhr to Munch, 25.02.1906

[10] Rolf Stenersen, Edvard Munch, Stockholm/Zurich, 1950, p. 87

[11] Letter from Gustav Schiefler to Munch, 01.02.1913, in Edvard Munch. Gustav Schiefler, Briefwechsel 1902-1914, vol. 1, ed. Arne Eggum, Hamburg, 1987, no 599, p. 453

[12] Letter from Munch to Gustav Schiefler, undated, ibid., no. 600, p. 453

[13] Stenersen, op. cit., p. 42, and Jan Thurmann-Moe, ‘Roßkur‘ und Firnis bei Edvard Munch, in Das 19. Jahrhundert und die Restaurierung: Beiträge zur Malerei Maltechnik und Konservierung, ed. Heinz Althöfer, Munich, 1987, pp. 112-121. See also Thurmann-Moe, Munchs ‘Roßkur‘. Experimente mit Technik und Material, Hamburg, 1994

[14] Stenersen, op. cit., p. 42.

[15] Cited and translated after Matthias Arnold, Edvard Munch. Mit Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten, Reinbek b. Hamburg, 1986, p. 135

[16] Munchmuseet, MM K 2819, letter from Max Linde to Munch, 16.04.1906

[17] Munchmuseet, MM K 2768, letter from Max Linde to Munch, 07.04.1903

[18] Stenersen, op. cit., p. 87

[19] Many of these original frames can be seen at the Kunsthaus Zurich

[20] Patrick Stoern from the Thielska Gallery in Stockholm kindly gave me this information

[21] The resemblance to Hans Thoma’s Adam and Eve (1897) was noted in the booklet Bild + Rahmen der Moderne. Van Gogh bis Dali, Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien, p. 8, which accompanied the exhibition catalogue In perfect harmony, ed. Eva Mendgen, 1995, Amsterdam and Vienna. German painter Heinrich Vogeler conceived a similar design for Twilight, featuring a frame with roots sprouting from a skull

[22] Arne Eggum and Cornelia Gerner suggest that there was at least one executed frame for one or more versions of the Madonna painted in oil. Edvard Munch. Liebe – Angst – Tod, exh. cat., Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Kaiser Wilhelm Museum Krefeld, Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern, ed. Arne Eggum, Bielefeld, 1980, p. 31; and Cornelia Gerner, Die Madonna in Edvard Munchs Werk, Frauenbilder im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, Morsbach, 1993, pp. 15-16

[23] Cf. Paul Mitchell & Lynn Roberts, A history of European picture frames, London, 1996, p. 114

[24] I would like to express my gratitude to the Archives of the (old) Munch Museum for granting me access to undigitized exhibition photographs

[25] I noticed Munch’s painterly treatments of these frames after Gerd Woll kindly pointed out to me that the painter extended the composition of Death of the Bohemian onto its frame. See Gerd Woll, Edvard Munch, complete paintings. Catalogue raisonné, vol. 3, London, 2009, no 1166, p. 1095, for a photograph of the frame, which is now lost

[26] Mitchell/Roberts, op. cit., p. 53 and 71

[27] See, for example, Edvard Munch, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, exh. cat., Galerie Thomas, Munich, ed. Dieter Buchhart, Munich, 2012

[28] Millie Stein, Edvard Munch and the ‘kill-or-cure’ remedy. Analysis of the Ekely Collection at the Munch Museum, ZKK 28, no 2, 2014, p. 279; and Thurmann-Moe, 1987, op. cit., p. 112

[29] Cited and translated after Eggum 1980, op. cit., p. 298

[30] Bouguereau’s interview was published in the newspaper L’Eclair (09.05.1891), cited in translation by Louise d’Argencourt, Bouguereau et le marché de l’art en France, in William Bouguereau 1825-1905, exh. cat., Petit-Palais, Paris; Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal; Wadsworth Atheneum, ed. Louise d’Argencourt, Paris, 1984, p. 100

[31] Munchmuseet, MM N 311, note, without date

[32] Munchmuseet, MM N 40, note, 1930-40

[33] Munchmuseet, MM T 2748, note in a sketchbook, 1927-34

[34] Cf. Isabelle Cahn, ‘Edgar Degas’, in In perfect harmony, op. cit., pp. 129-162

[35] Jules Clarétie, ‘La vie à Paris’, in Le Temps, 5 April 1881; also cited in Cahn, ibid., p. 132

Excellent article, clearly written and beautifully illustrated. Thank you!

LikeLike

Wonderful!! Like Munch’s frames—no further “embellishments” required. Kudos to you and your scholarship.

LikeLike

I’m so glad that you enjoyed it – the author was Dr Marei Döhring, though, rather than me…

LikeLike

Excellent paper! Thanks for publishing!

LikeLike

That is very kind – thank you for taking the time to comment…:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for reading my paper!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, Marei (and Lynn),

I thoroughly enjoyed this article. Interestingly, the National Museum in Oslo has numerous Munch paintings framed in carved and gilded frames, including The Scream from 1893. Do either of you know anything about the frame on that version? Marei, were you able to go to Oslo to view the Munch Museum and their copies of The Scream? What were the previous frames like before they were reframed for the new Munch Museum?

Warmest regards,

Barrie in the USA

LikeLike