Histories of the frame

This paper on the historiography of frames was written for the recent online conference (‘Many lives: Picture frames in context’; 25-26 September 2024) organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

Art history is still quite a young discipline itself, and has only been formally taught from around the 1840s and 50s; whilst the history of picture frames has – very disgracefully – never been taught consistently anywhere at all. It has been left to maverick students, looking for new ground to colonize for their dissertations; to conservators giving talks on their recent work; to specialist schools, sponsoring occasional lectures on peripheral subjects; and to rare frame conferences like this one, which pull together specialists in different areas to speak about various aspects of the frame today and through time.

Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), frames (post-1524) around drawings (c.1480-1504) by Raffaellino del Garbo & Filippino Lippi from the Libro de’ disegni, NGA, Washington

Vasari, framed portrait for the essay on Botticelli in Le Vite de’ Piu Eccellenti Pittori Scultori et Architettori…, 1550 & 1568, Royal Collection Trus https://www.rct.uk/collection/1152361/delle-vite-de-piu-eccellenti-pittori-scultori-et-architettori

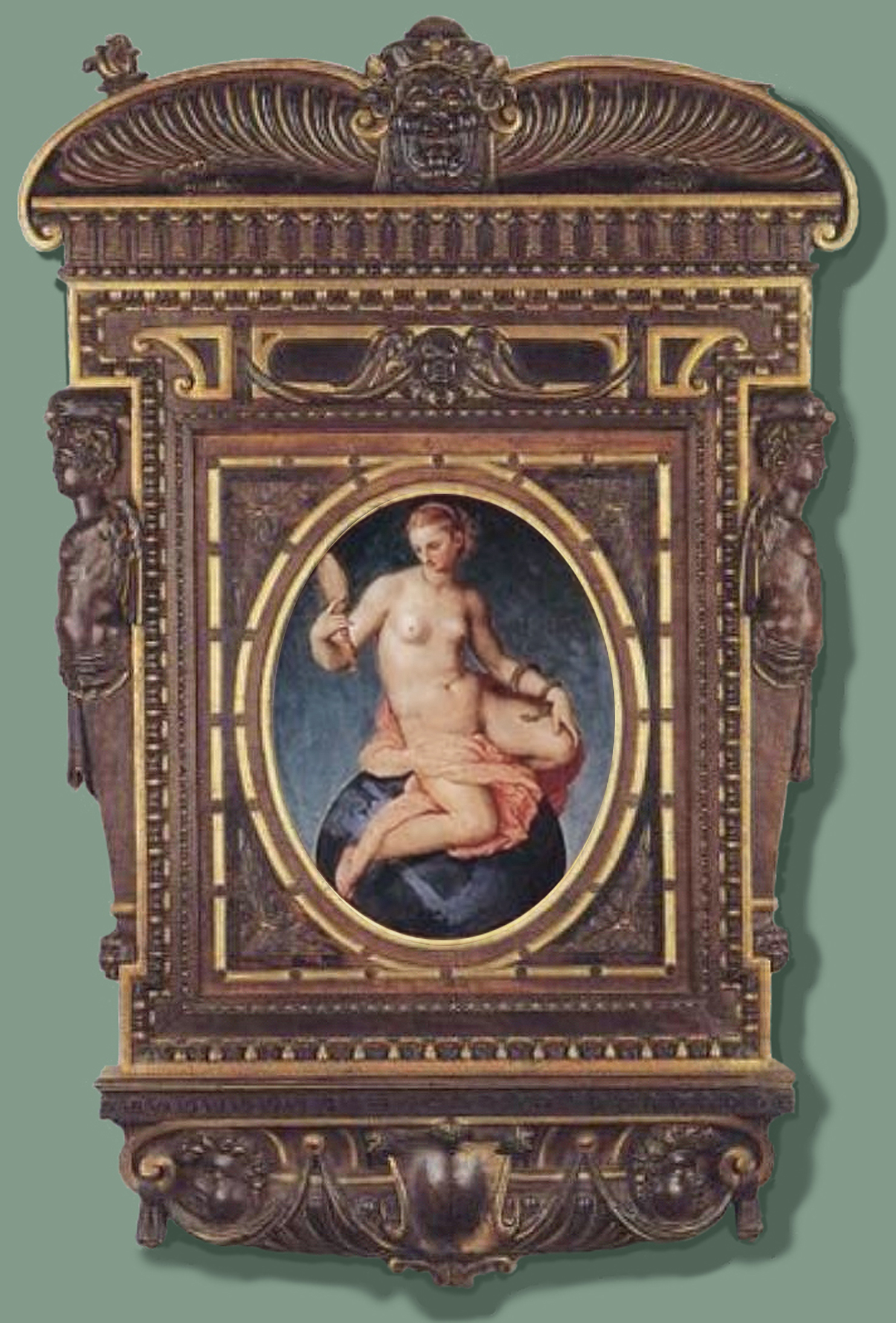

Vasari, Mannerist looking-glass frame in parcel-gilt walnut carved by Alessandro Allori, with the Allegory of Prudence painted by Vasari on the cover, Casa Vasari, Arezzo

Frames, of course, do crop up in books on the history of art – ever since the 16th century and Vasari, who is often referred to as the father of the subject, and who thoroughly realized the importance of the framing device to the image within. He included pen, ink and wash frames around his own collection of other people’s drawings in his Libro de’ disegni; engraved designs around the portraits of artists in his Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects; and had a wooden frame with a painted cover carved to his own design for a looking-glass in his house.

Margharito d’Arezzo (fl.1260s), Virgin & Child enthroned, c.1263-64, tempera on panel, 92.1 x 183.1 cm., National Gallery

He also mentions historical frames directly – for instance, he notes that, in the mid-13th century, Margharito of Arezzo

‘…made borders and diadems and other rounded ornaments in relief; and it was he who invented the method of introducing bosses on which he laid gold-leaf which he afterwards burnished’.

Vasari, ‘frame’ around a drawing by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-94) from the Libro de’ disegni, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

It is the frames in the Libro de’ disegni, though, which are most striking and revealing. Looking at the vividness with which his pen-&-ink borders are married to the studies they contain, transforming them into complete works of art, it is difficult to understand why the importance of the frame as the vehicle of presentation and display hasn’t lasted along with the study of the paintings which they contained. The only place where it seems to crop up today is in post-modern papers which are rendered almost incomprehensible by their vocabularies.

We can be fairly certain that Vasari wasn’t contemplating the figures on the frame he gave to Ghirlandaio’s old man as ‘deictic cues’. These particular four women are there to expand upon the meaning of the drawing (sometimes referred to as the Head of a dead man) by filling the place of mourners on the frame of a carved, wall-mounted tomb. They are at the same time a slightly macabre jeu d’ésprit on Vasari’s part, and an expression of authentic emotion matching the dignity given to the subject of Ghirlandaio’s drawing. The four of them might have decorated a carved giltwood picture frame, if there had been space for a larger structure; as it is, they are pushed into the corners of the paper, and given the realism found in engraved portrait frames in the 17th century. The two caryatides at the top perform the function of drawing back curtains to disclose the dead man, as though he were lying in state in a chapel. Without these funereal handmaidens, the drawing might have remained what it is also called, the Portrait of a man with his eyes shut; as it is, Vasari has interpreted it for himself and all those who look at it, as well as displaying it like a full-scale work of art in a decorative setting.

Vasari, ‘framed’ drawings, including a ‘Sansovino’ frame around the lower drawing by Lorenzo Sabatini (c.1530-76), Libro dei disegni, Musée du Louvre

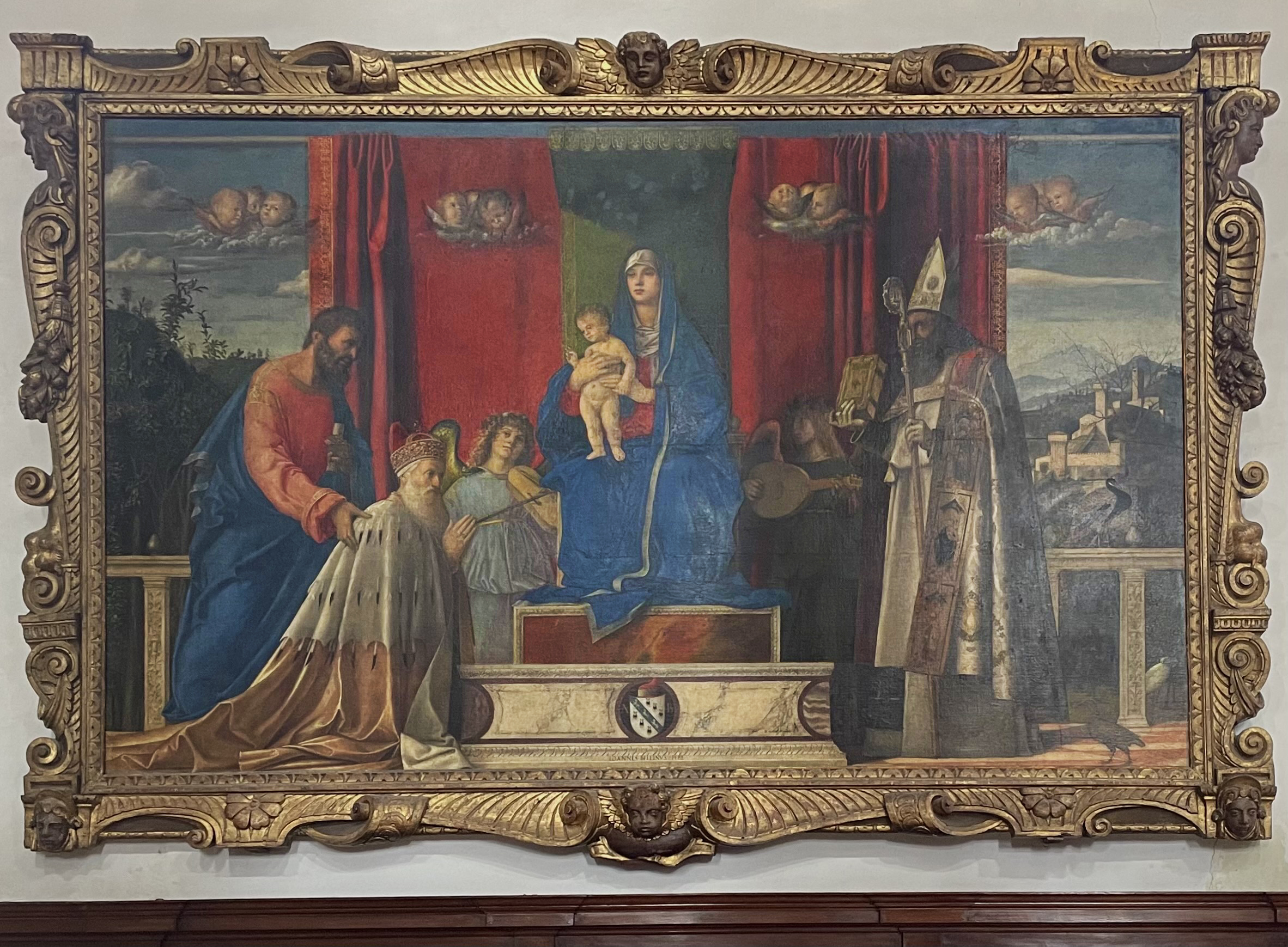

He has given a drawing by Lorenzo Sabatini for the Last Supper an even more realistic frame: carefully shaded to create volume and the effect of undercut layers of carving, it replicates a contemporary ‘Sansovino’ frame, giving Sabatini’s drawing the immediate status of a framed altarpiece, such as the Bellini, below.

Giovanni Bellini, The Madonna & Child with Doge Barbarigo, 1482, in a later ‘Sansovino’ frame, San Pietro Martire, Murano, Venice

It suggests how a Mannerist painting in this style might have been displayed in the Bolognese monastery it was designed for, and that perhaps Vasari was aware of ‘Sansovino’ frames in location other than Venice.

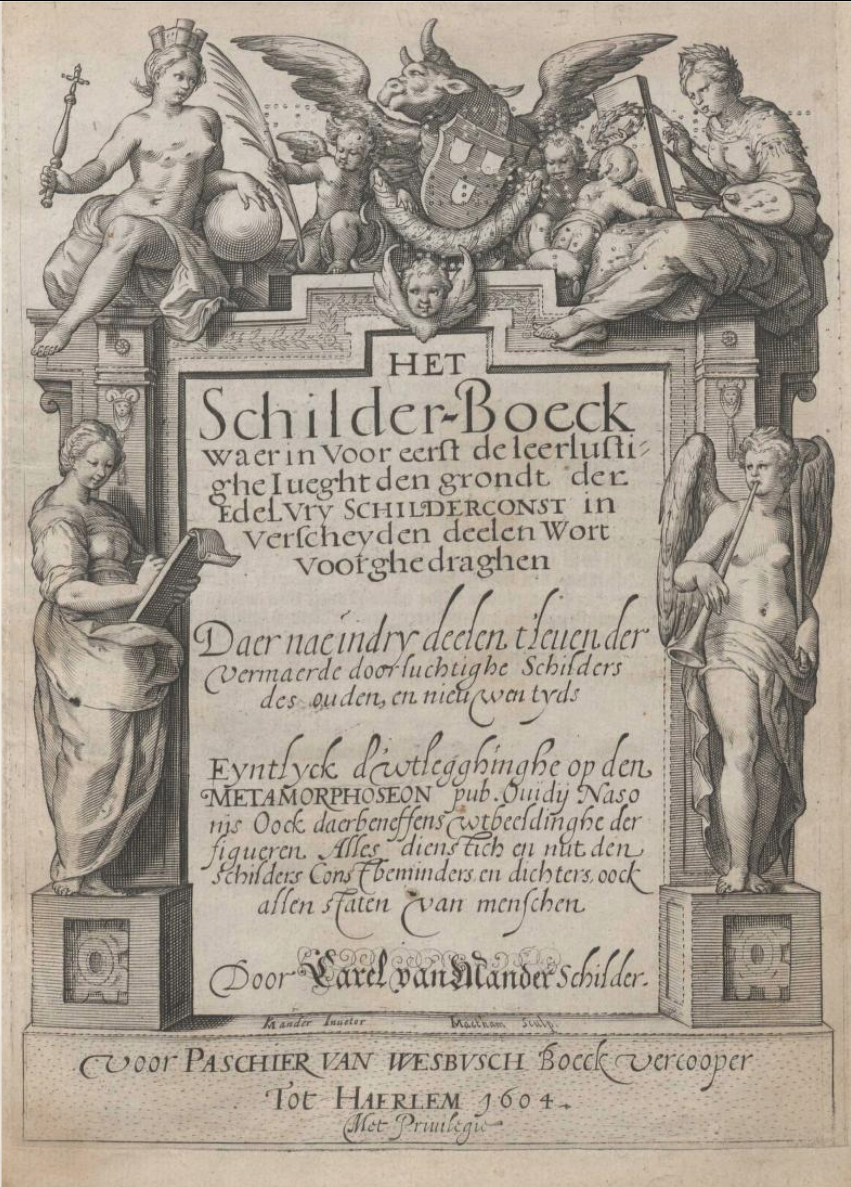

Karel van Mander (1548-1606), Schilderboek, 1604, frontispiece

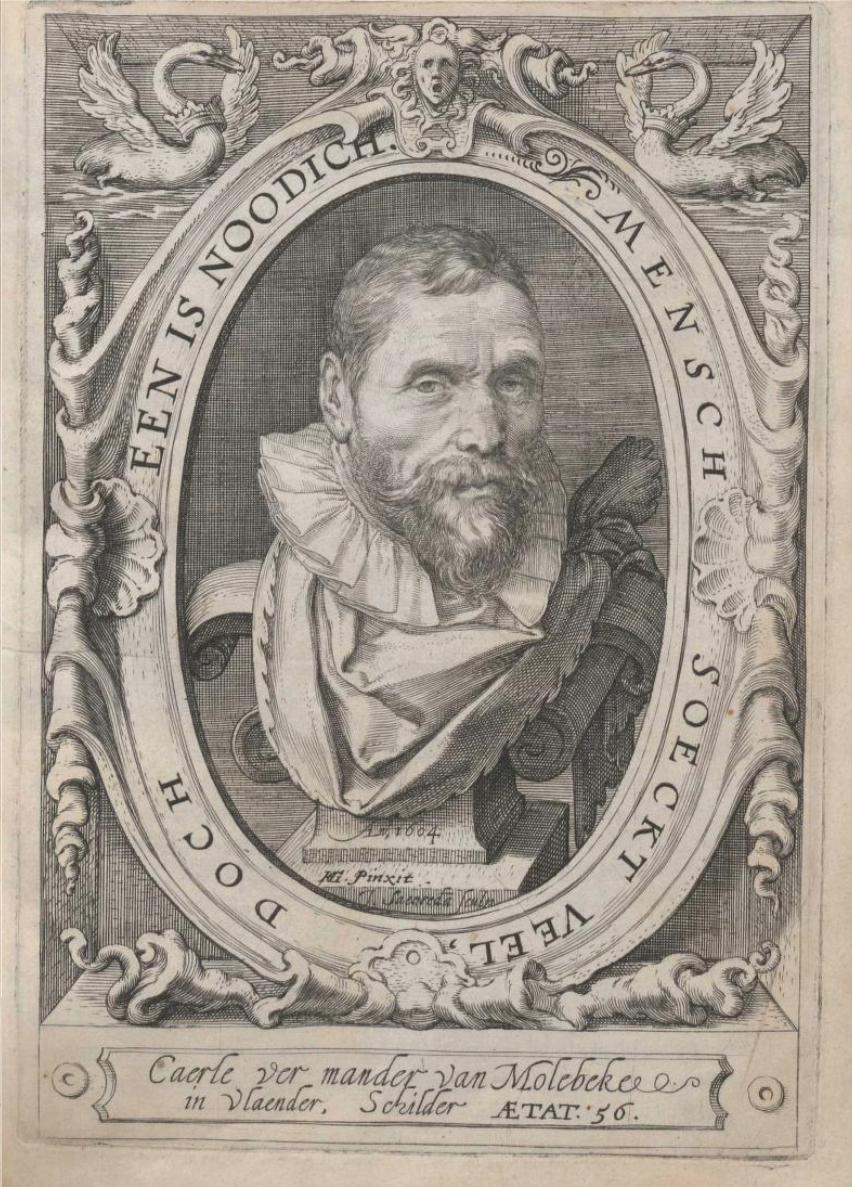

Karel van Mander (1548-1606), Schilderboek, 1604, author’s portrait

Vasari’s framing of the drawings he had collected was not something copied – or, probably, much known about – by the art historians who followed him. Karel van Mander, who translated and added to parts of the Lives of the painters…, didn’t include their engraved and framed portraits in his 1604 Schilderboek – although the frontispiece is strikingly presented as a Mannerist aedicule, supporting figures of Architecture, Drawing, Painting and Fame, and the author’s portrait is given an oval Auricular frame complete with rather unsavoury-looking organic scrolls.

Johannes Lutma (artist & engraver; 1584-1669), Hans von Aachen painting Paulus van Vianen, c.1653, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Hubertus Quellinus (artist & engraver; 1619-87), Portrait of Artus Quellinus I (teacher of Grinling Gibbons), from Architecture, peinture et sculpture de la Maison de Ville d’Amsterdam, published 1719

This type of engraved portrait had become customary in books by the 17th century, and had grown out of the earlier custom of providing integral frames for individually-sold engravings made from paintings. They were never commented on, however, and although based on real frames, they inevitably included imaginary and fantastic elements.

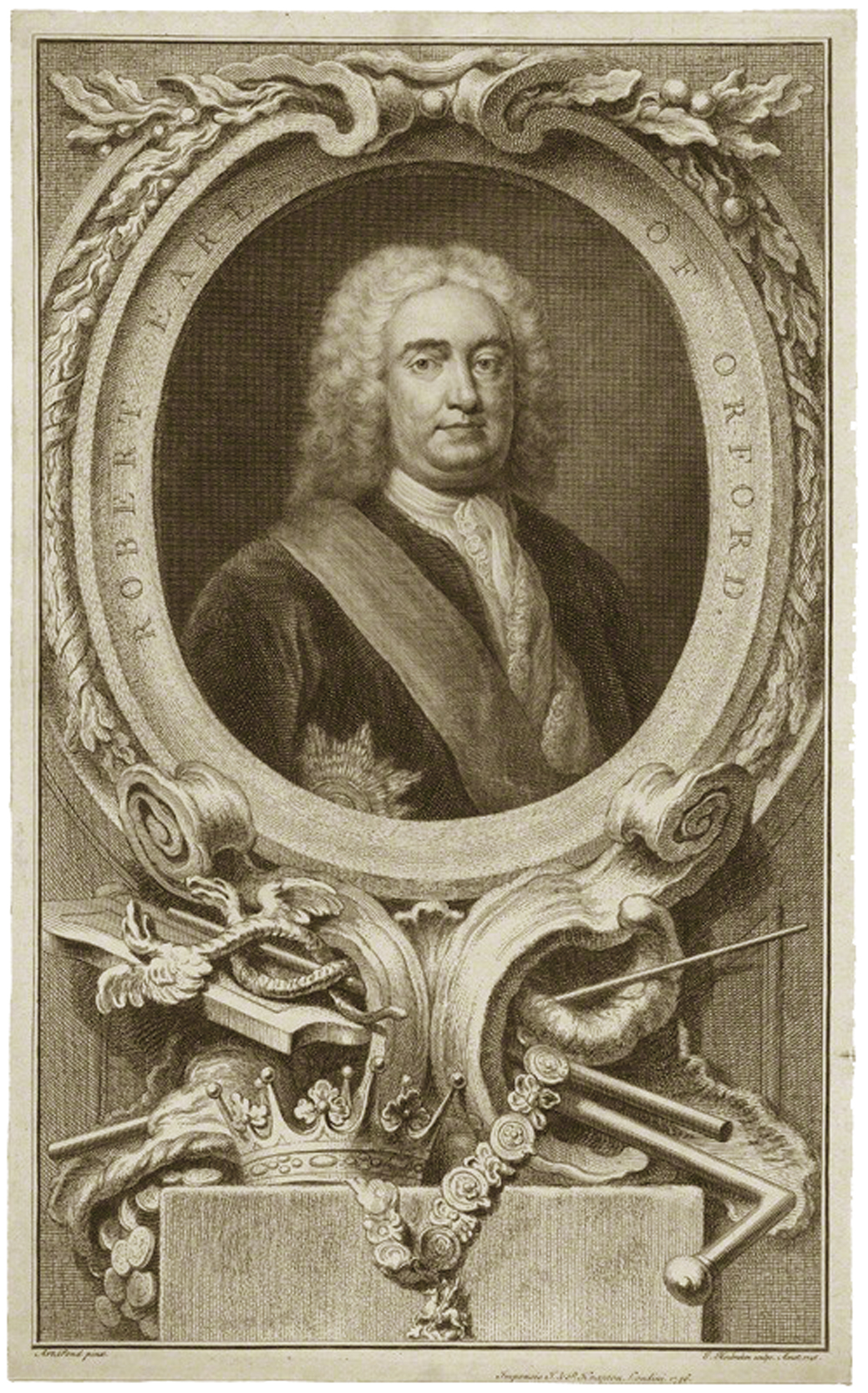

Arthur Pond (after; 1701-58), Jacobus Houbraken (engraver; 1698-1780), Portrait of Robert Walpole, published 1746, National Portrait Gallery

Marilly (artist), P-A. Le Beau (engraver; 1744-1817), Portrait of Comtesse du Barry, 1770-80, BnF

While Vasari had used his frame collages to perform much the same purpose for his collection of drawings as frames in a real picture gallery, the frames of engraved portraits were divorced from any physical purpose, and – although looking in some ways identical with wooden frames – became just another accoutrement of the sitter, like his costume, to be played with.

Perhaps this helps to explain why a branch of the arts, which during the 14th to 16th centuries had produced altarpieces in partnership between carvers, gilders and painters working on equal terms, became decreasingly important in comparison with painting, and was hardly likely to be written about in the same terms as the work of Michelangelo or Rembrandt.

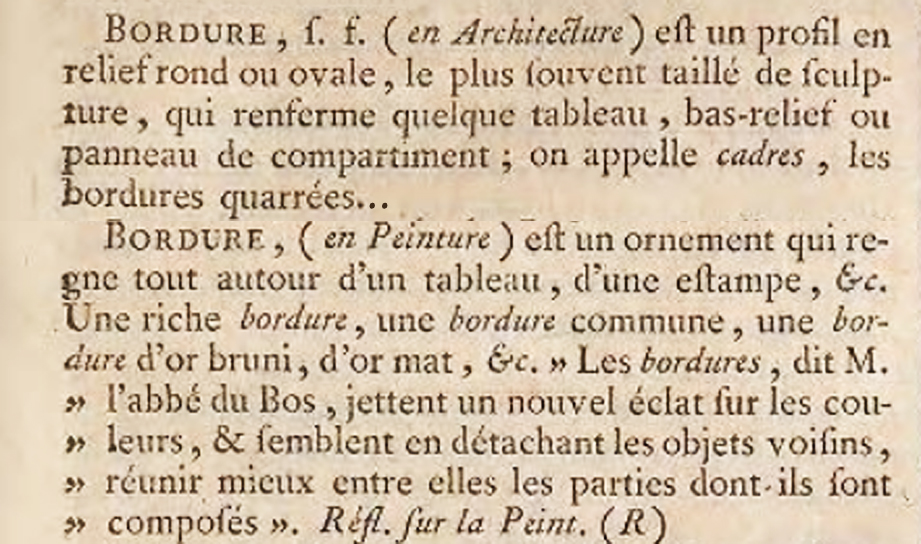

Diderot’s mid-18th century Encyclopédie is really the first work to get to grips with what a frame or ‘bordure’ is, either for a painting or print, or a stucco division on a decorated wall or ceiling. His explanations are disappointingly brief, although backed up with a quotation from Reflections on Painting by the Abbot du Bos.

Diderot & Alembert, Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, 1751, vol. 2, p. 335

https://archive.org/details/EncyclopeYdieouIIDide/page/334/mode/2up

‘Frame [bordure] (in architecture) is a section in relief, either round or oval, usually carved with ornament, surrounding a painting, bas-relief or plain compartment panel; versions of this with a square profile are called ‘cadres’…

‘Frame [bordure] (in painting) is the ornamental margin which commands the outer edge of a painting, a print, etc. A rich border, a plain border, a border of burnished gold, matte gold, etc. ‘Frames,’ says the Abbot du Bos, ‘throw a new brilliance onto colours, and seem, by causing neighbouring objects to stand out from each other, to unite better the parts of which they are composed.’ ’

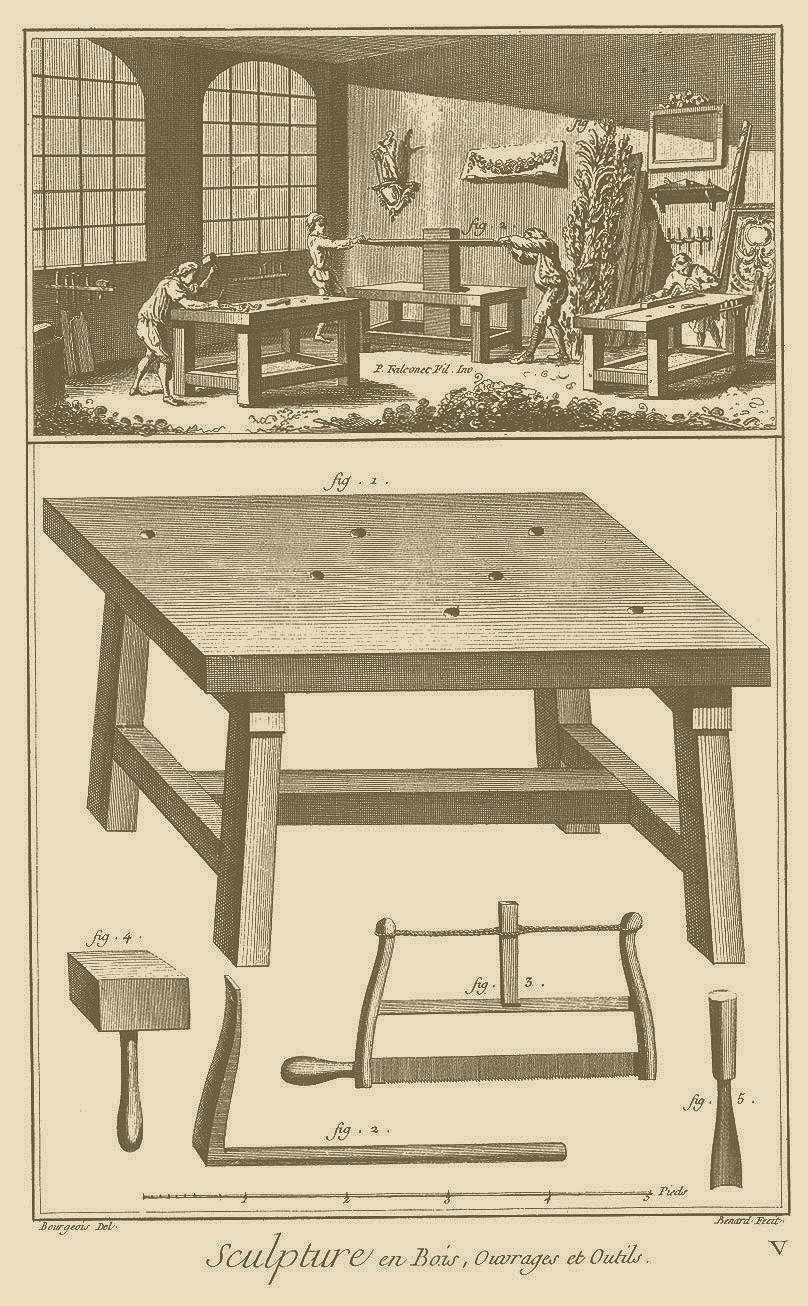

Diderot, Encyclopédie, vol. 8, plates; plate 1: Sculpture en bois

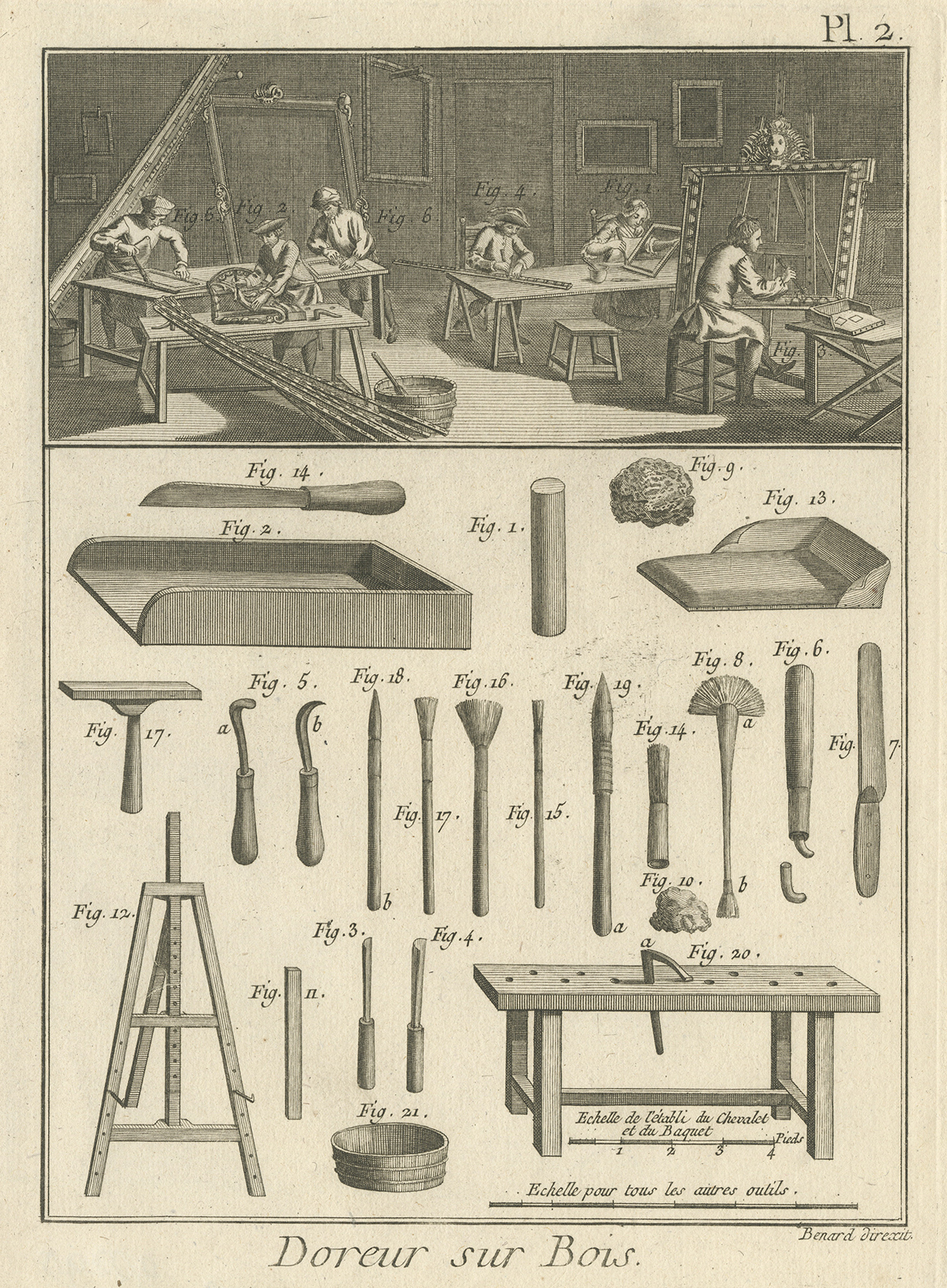

Diderot, Encyclopédie, vol. 8, plates; plate 2: Doreur sur bois

The Encyclopédie has one volume composed of plates of illustrations for the whole work, amongst which – rather than images of, for instance, examples of frames in different styles – there are scenes of workers in various fields (the ‘métiers’ of the title). The plate for ‘Sculpture en bois’ shows carvers and joiners in a workshop producing panels of decorative boiseries for the interior of a room, figural sculptures, and picture frames; whilst another more famous plate has people gilding and finishing frames. For the Encyclopédie, frames are technology, rather than art.

Henry Havard, ‘Cadre’, Dictionnaire de l’ameublement et de la décoration, 1887, vol. 1, pp. 511-16

Diderot’s massive work was followed, 130-odd years later, by Henry Havard’s Dictionnaire de l’ameublement et de la décoration. Havard – under ‘Cadre’ in vol. 1 – takes a quick scamper in six pages through the history of the frame from the 16th century to the 1880s, and adds four images: a ‘Sansovino’ frame on a rather surprised French Renaissance woman, another empty Mannerist frame covered with scrolls and masks and animals, a Baroque looking-glass, and an oval NeoClassical frame with trophies of love and music.

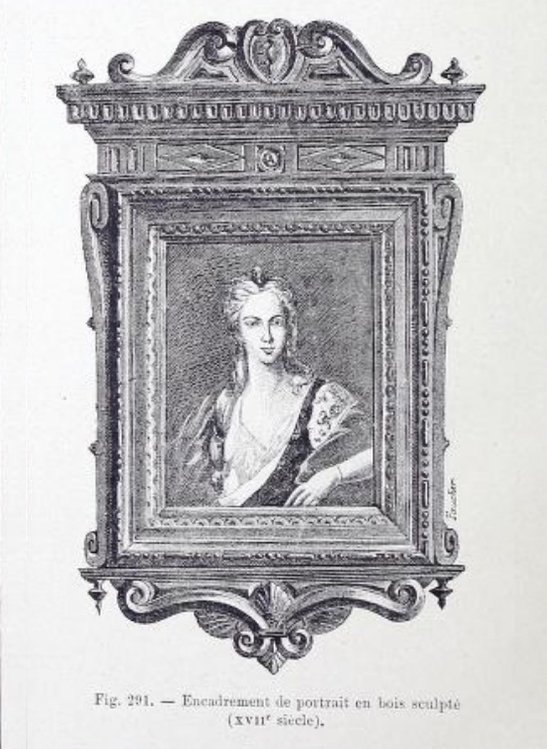

Henry Havard, ‘Encadrement’, Dictionnaire de l’ameublement et de la décoration, 1887, vol. 2, pp. 425-31

In vol. 2, more than five closely-printed pages of information on framing and framemakers follow, along with images of a sculptural door frame, two tapestry frames, a looking-glass, a portrait in a Mannerist frame, and the trompe l’oeil painted frame for a mural in Versailles. These are probably the earliest and most comprehensive – if still quite brief – published pieces on different types of frame and their histories; Havard’s Dictionnaire… is the first book to offer illustrations of individual frames along with this information; and it is the place where any historiography of frames must begin.

Michelangelo Guggenheim (1837-1914), Palazzo Balbi with showroom and workshop, Venice

The next most notable and influential book on frames was written by the collector and dealer, Michelangelo Guggenheim, who was also a manufacturer of revival furniture in Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo styles. He had been born to German parents in Venice in 1837 and had inherited their collecting tastes, taking their small antiques gallery to an empire-building level, with three large workshops, a global export business, and a prestigious shopfront in Palazzo Balbi on the Grand Canal.

Michelangelo Guggenheim (1837-1914), Le cornici italiane, 1897

In 1897 he published Le cornici italiane, an album of important Renaissance frames on a grand scale, from the mid-15th to the end of the 16th century. It comprised 100 black-&-white plates showing a total of 120 frames, with a 19-page history of the subject, and drew on his phenomenal knowledge of his subject – perhaps especially of antique woodwork.

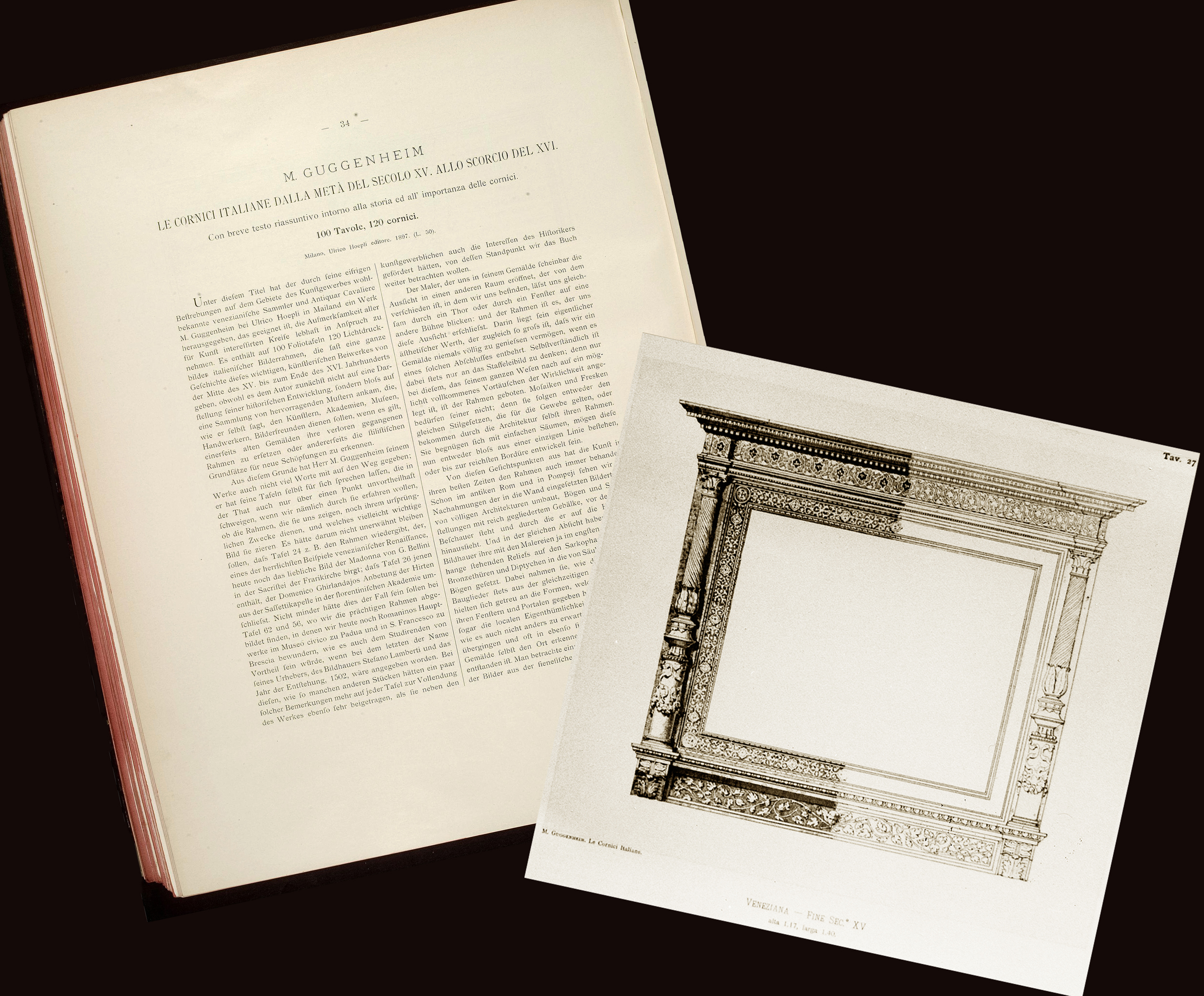

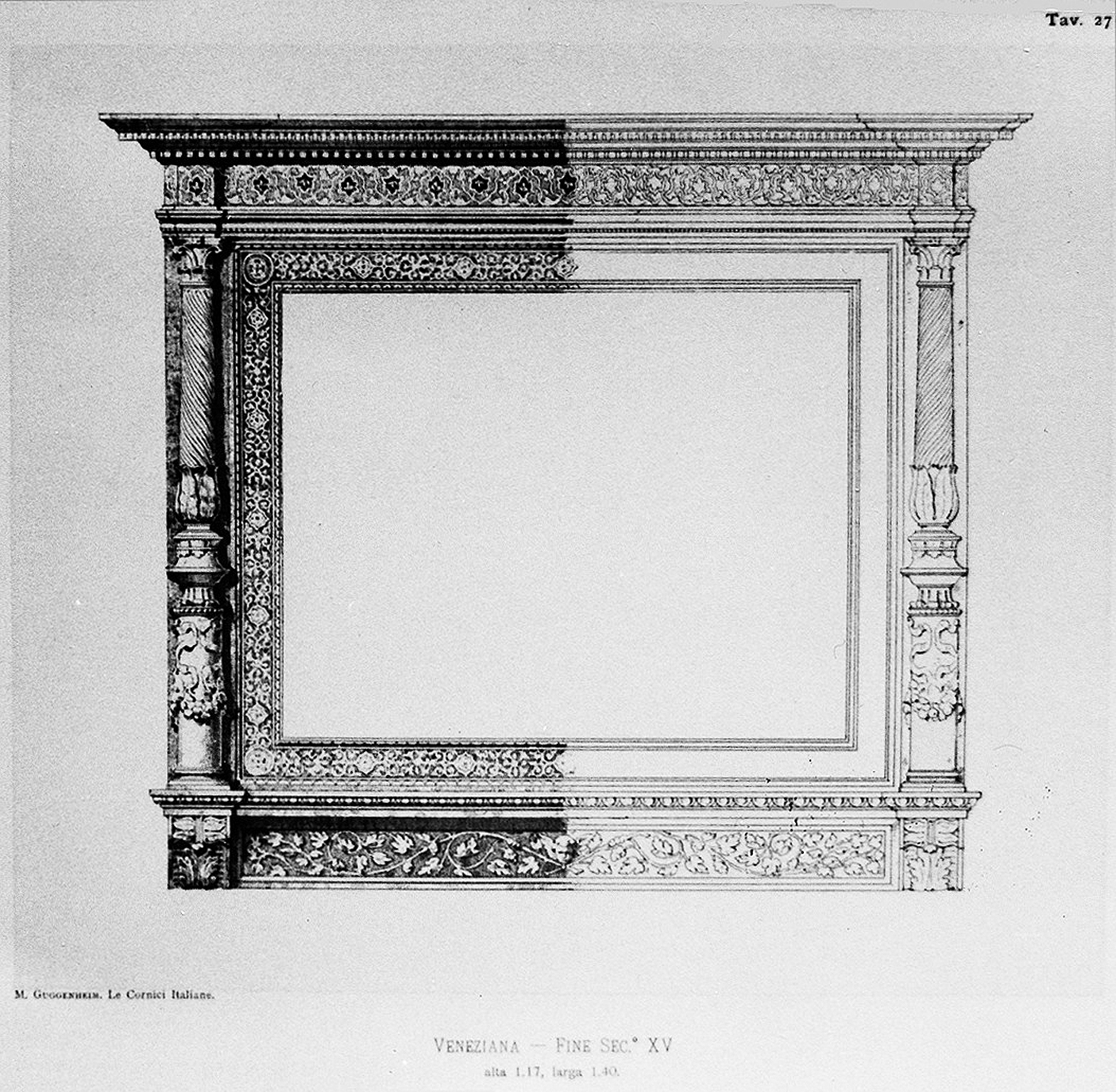

Guggenheim Le cornice italiane, 1897; text and plate 27

Andrea Previtali (c.1480-1528), Madonna & Child & saints, c.1503, original frame, sacristy of San Giobbe, Venice

The 120 frames he illustrated were the best specimens he knew of amongst Italian Renaissance patterns, including, for example, the little-noticed original frame on Previtali’s Madonna & saints, hanging unregarded in the sacristy of San Giobbe. He was not only concerned with recording their history, but also with explaining the effect which frames could have on paintings, and the advantage a picture could gain from being properly framed. This combination of knowledge and connoisseurship meant that his book quickly became a classic reference work, used in schools of art and design and influencing the choices made by curators, artists, exhibition designers and collectors [1].

M. Guggenheim, Le cornici italiane…, 1897, plate 27: ‘Venetian – end of the 15th century, 117 x 140 cm.’

Duveen Brothers Records, 1876-1981, The Getty Research Institute, Accession no 9600015; painting from Benson Collection framed by Ferruccio Vannoni (1881-1965) in a design based on Guggenheim, plate 27

It was taken up enthusiastically by dealers like Joseph Duveen. The Duveen brothers had built up a sizeable transatlantic traffic in paintings from the homes of impoverished British aristocrats to the opulent houses of American entrepreneurs. These works sold much better when they were set off by richer, less shabby or more chronologically connected frames, and Guggenheim’s illustrations became a pattern-book for reframing Italian Renaissance paintings. The page, immediately above, from a Duveen album of photos is marked ‘Veneto’ for the style of frame, ‘Benson’ for the collector to whom this painting had belonged, and ‘Vannoni’ for Ferruccio Vannoni.

Vannoni was a Sienese carver and gilder who had established a business in Florence, and did a great deal of work for Duveen [2]. He was able not only to copy antique frames accurately, but to adapt them in size, proportion and detail, making him doubly valuable to Duveen, and the Guggenheim illustrations even more useful.

Alvise Vivarini (c. 1445-c.1503/05) & Marco Basaiti (1470-c.1530), Madonna & Child with John the Baptist & St Jerome, late 15th century, frame by Vannoni, Harewood House

Private clients, such as the 6th Earl of Harewood, also employed Vannoni; here is another example of the Previtali frame with proportions similar to the original, and with different details from the Duveen version. This use of Guggenheim’s work in different countries and for private collectors and museums indicates the great hunger there was in the late 19th and 20th centuries for accurate information on antique frames, and for illustrations of original frames as references. Some collectors and curators really wanted to be able to display their paintings in a fashion approximating, as nearly as possible, the original context.

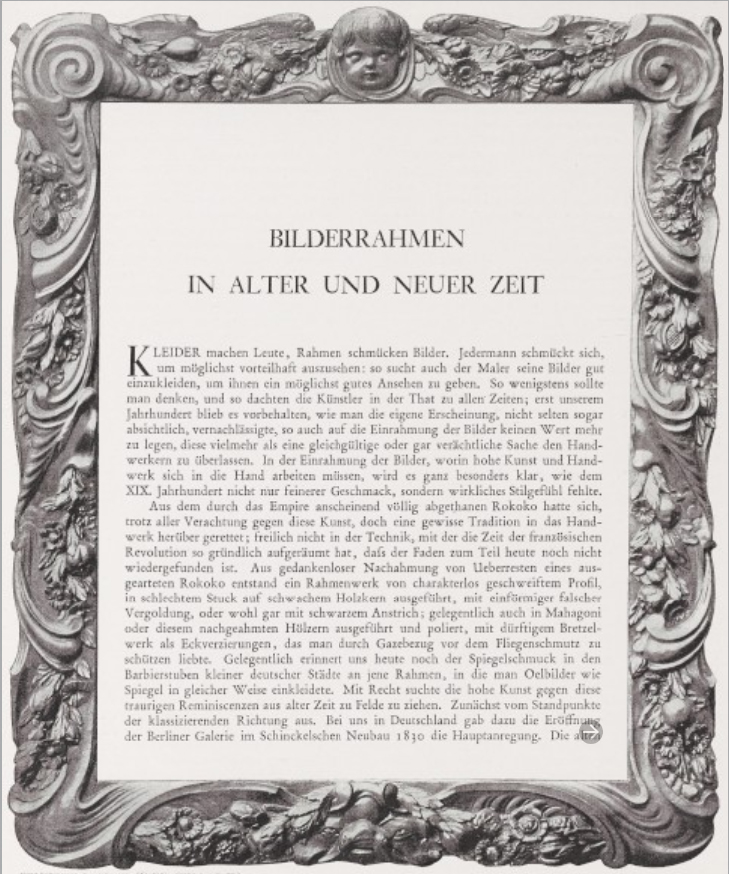

Wilhelm Bode (1845-1929), ‘Bilderrahmen in Alter und Neuer Zeit /Picture frames in the past and present’, Pan, 1898, vol. IV, no 4, pp. 243-256: first page with Netherlandish Auricular frame

Emanuel de Witte (1615/17-91/92), Interior of the Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, 1670-90, o/panel, in the frame illustrated in Pan; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

One particular museum curator who was intensely interested in the concept of appropriate framing was Wilhelm Bode, who directed the Gemäldegalerie and later the combined museums of Berlin in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was friends with both Michelangelo Guggenheim and his exact contemporary, the Florentine dealer Stefano Bardini [3], corresponding with them and buying from them both in his quest to set up a museum which would present all kinds of art in an integrated display. This vision meant that he wanted both paintings and relief sculptures to be framed as authentically as possible, an idea which he achieved in the 1890s, and which inspired him in 1898 to write a history of frames. It was published in the journal Pan as ‘Picture frames in the past and present’, and is the first comprehensive and serious history by an art historian and museum curator.

Wilhelm Bode, illustration of a Sansovino frame from Pan

Bernardino Luini (1480-1532), Madonna & Child with an apple, c.1510-25, o/panel, 53 x 42 cm., in the frame illustrated in Pan; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. Photo: Sailko

Bode was an expert in many areas, writing about Italian Renaissance painting, sculpture, majolica, bronzes, furniture and tapestry, as well as producing studies of Rembrandt, Leonardo, Botticelli, and others. With the help which Guggenheim and Bardini could give him from their practical experience, he was perfectly placed to write a history of the one thing which united all the disparate elements of an interior – the frame. His article is motivated partly by disgust with the frames of his own age – the meretricious revivals of older styles, made in cheap wood and stucco and brightly gilded – and partly by his work, reframing Old Master paintings for the Gemäldegalerie. This process, which brought him into close contact with Guggenheim and Bardini, taught him a great deal about the original frames of different periods and nations.

His favourite nationality was Italian, and his favourite time the Renaissance through to the Baroque, closely followed by the Low Countries in the 17th century and their Mannerist frames – Lutma, Auricular and trophy. Italian frames and their development – especially in Florence and Venice – take up six pages of the thirteen-&-a-half pages of text in the article, Netherlandish three, and the introduction another three, leaving very little room for French frames, whilst Spanish and English frames are barely mentioned.

Bode’s history is thus heavily weighted in the direction of his own interests, and where he feels the true artistry of frames lies. He thinks that Bolognese frames are expressionless, uniformly finished and boring, ‘like all Bolognese art of that time’ [4], and since ‘the Bolognese frame of the 17th century became the starting point of the French Baroque frame’ [5], French frames are definitely handicapped in reaching their full potential.

A display of paintings, sculpture and sculptured reliefs, furniture and applied arts in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, Berlin (later the Bode Museum), 1919-33, centred on a framed relief of the Madonna & Child by Antonio Rossellino, c.1460-70. Photo: © Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Skulpturensammlung, Archiv

Raffaellino del Garbo (1466/70-1524), Portrait of a young man, c.1505; a survival, with its frame, from the display in the pre-war photo of the Bode Museum

It is depressing that so much knowledge and effort should have been expended on producing what must have been the ultimate museum, only for many of the frames – which were often stored separately from the paintings during the Second World War – to be destroyed. It is not possible to match colour photos of the frames to all of Bode’s black-&-white illustrations, in the same way as the Auricular frame on the Emanuel de Witte and the Sansovino frame on the Luini, because they no longer exist. The Rossellino relief of the Madonna & Child, at the centre of the hang in the museum (above), was also caught in a wartime fire, and broken. The relief could be patched up, because a plaster cast of it had escaped undamaged; however, the beautiful tabernacle frame, with its acanthus leaf apron, segmental pediment and delicately carved acroteria, has completely vanished.

Bodes’s viewpoint is slanted – he believes that even ‘the Rococo picture frame was less developed in France and England than in Germany’, although he’s quite keen on Louis XVI and NeoClassical styles – but it is his knowledge of Renaissance frames, his wish to educate the art world in that knowledge, and his vision of a museum where paintings and sculpture are displayed in the context of other arts, and with authentic frames, which are so clear and appealing to us today [6].

From the late 1870s, the literature on frames began to increase – helped, for instance, by the articles which critics began to write on the frames of the Pre-Raphaelites and Impressionists. These were generally single, focused essays, sparked by the radical influence of scientific theory on art, the influence of Japanese motifs, the wave of individually-designed frames by the artists themselves, the appearance of plain white frames in an era of wall-to-wall gilded ornament, and the even greater shock of frames in colours complementary to the paintings.

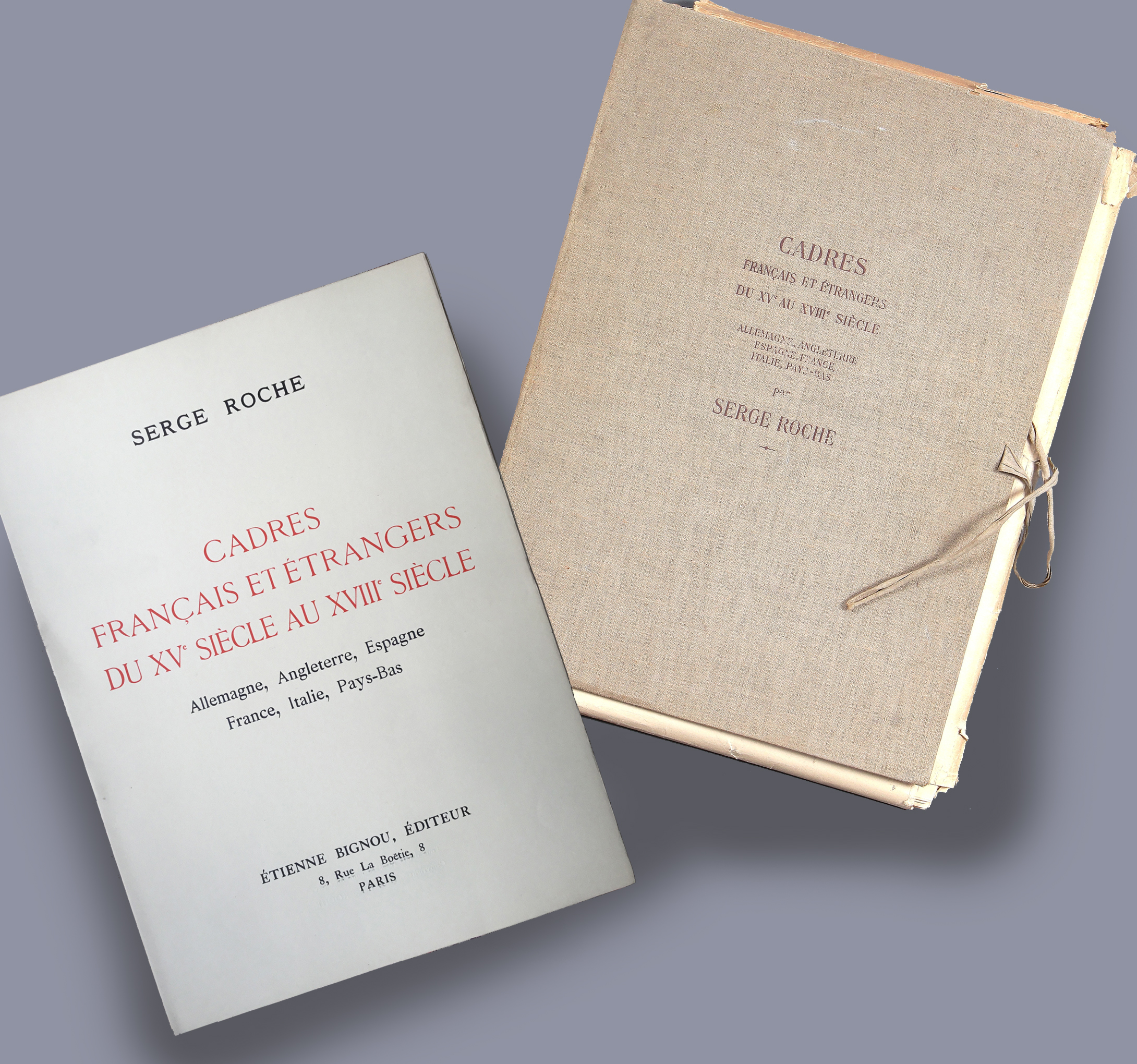

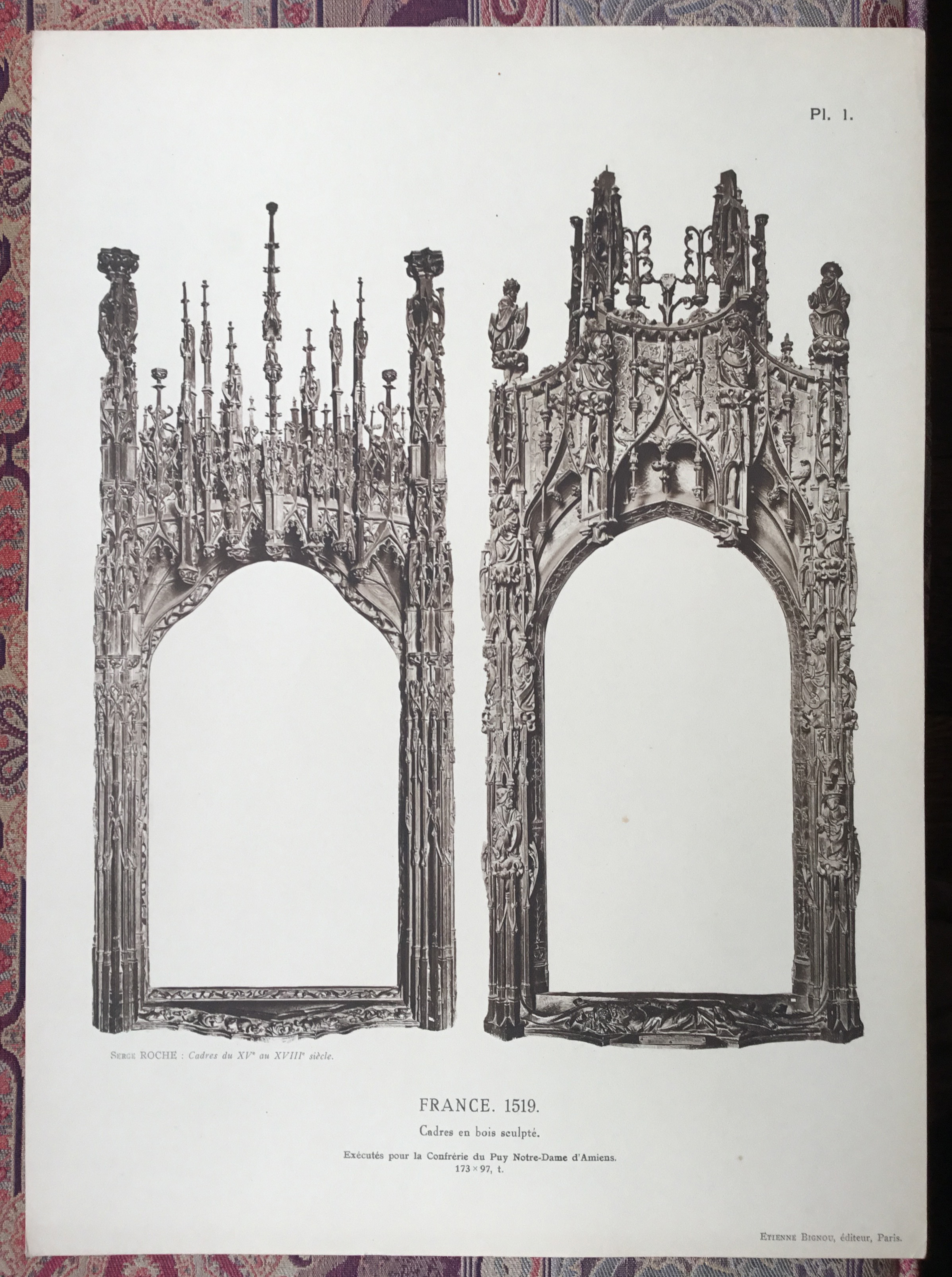

Serge Roche, Cadres français et étrangers du XVe siècle au XVIIIe siècle, Paris, 1931

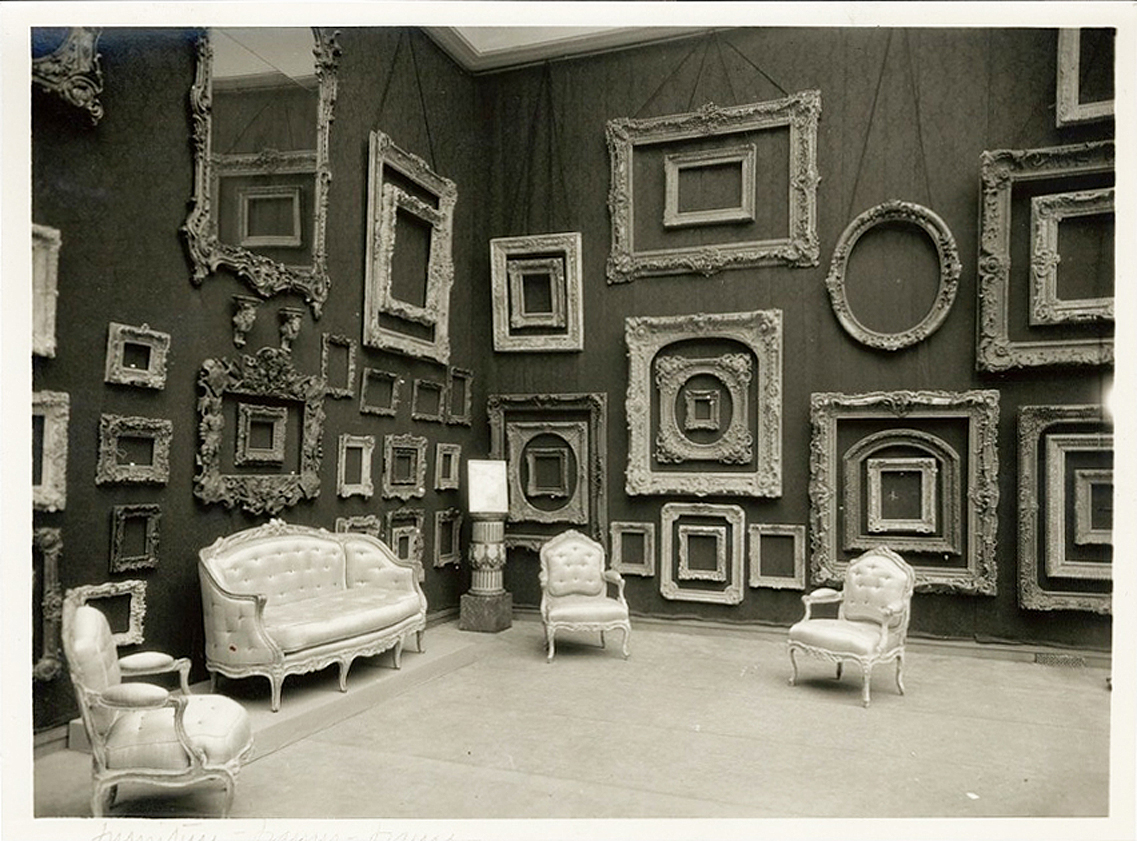

A view of Serge Roche’s frame exhibition, Exposition internationale du cadre du XVe au XXe siècle, at the Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, in 1931

However, the generalized study of the history of frames continued to evolve around and beyond these smaller, contemporary fashions. It took various forms, and as with the history of art, it continued to rely on the expertise of the collector and dealer. In the first half of the 20th century, one of most influential of these was the Parisian designer Serge Roche, son of an artist and antique dealer, whose major work is the great folio of black-&-white photos of antique frames which he assembled to accompany his 1931 exhibition of frames in Paris. This combined project was a flamboyant sweep across the panorama of historical European frames, from the 15th to the 20th century, each one identified by its nationality and date, with other facts such as material, location and dimensions where they were known and relevant. Particularly good specimens in museums and private collections filled out Roche’s own frames in the folio, allowing him a more complete historical overview.

Serge Roche, Cadres français et étrangers…, Plate 13

Louis XIV carved giltwood trophy frame on an antique looking-glass plate, 117 x 122 cm., Christie’s, London, 6 December 2012, Lot 8

He introduced his audience to French frames from the early 16th to the 18th century, redressing Bode’s emphasis on Italy and dealing with English, Spanish, Northern and German frames, as well as Italian. Because he included so many fine examples from museums and private collections, the folio as whole is far more than an accompaniment to his exhibition, splendid and innovatory as it was: it is a paean to the status of the frame as a piece of virtuoso sculpture – sometimes one with a whole narrative laid out in its composition, or with a complex symbolic programme; sometimes one where the rhythm of the decoration aspires to the condition of music; always with the magical skills of the carver fully revealed.

Serge Roche, Cadres français et étrangers…, Plate 1

Altarpiece for the Confrérie du Puy du Notre-Dame d’Amiens, Pour nostre foy militante comtesse, 1525, Musée de Picardie

Altarpiece for the Confrérie du Puy Notre-Dame d’Amiens, Pré ministrant pasture salutaire, 1519, 173 x 97 cm., Musée de Picardie [7]

The inclusion of three out of five surviving early 16th century altarpiece frames from the cathedral of Amiens, ranging in height from 173 to 383 cm. (5 foot 8 to 12 foot 6), beautifully and sharply photographed in black-&-white, discloses the relationship of such altarpieces to architecture, marble funerary sculpture and metalwork shrines; and – because they are shown without their paintings – the viewer is forced to see them not as mere accessories, but as soaring Gothic chapels with columns of petrified trees and forests of finials, inhabited by figures, beasts and birds.

There are two more important general histories of frames and one more 20th exhibition which everyone interested in the subject should know about; although the last quarter of the century had already seen it reach a tipping-point at which it had begun to split into more specialized and focused studies.

Henry Heydenryk, The art & history of frames, 1963

The first of these histories is by Henry Heydenryk, a member of a firm of framemakers which was founded in Amsterdam in 1845, added branches in Belgium and London, and finally in 1936 opened a branch in New York. Heydenryk’s book, The art and history of frames, published in 1963, begins in the 13th century, continues to the later 19th century in Europe, and includes two Spanish frames in its collection of 100 images. For the first time, it also includes a section on American frames from the 18th century, taking the history up to the mid-20th century.

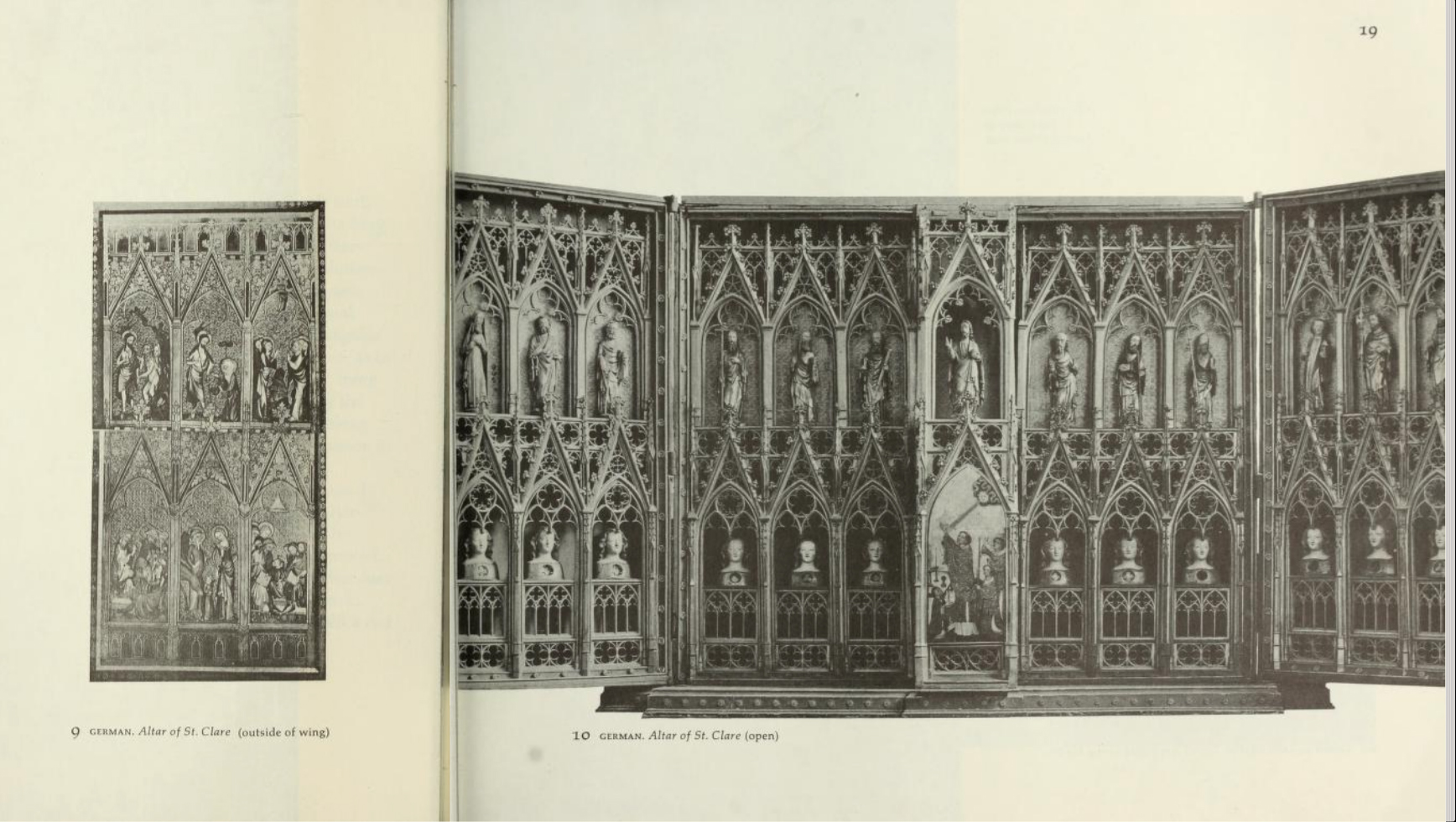

Heydenryk, figs 9 and 10, German school, Altarpiece of St Clare, Cologne Cathedral

German school, reliquary Altarpiece of St Clare, commissioned c.1360 for the Franciscan Convent of St Clare; now Cologne Cathedral

It is extremely readable, succinct, and very well-illustrated, and is the sort of book which ought to be on the bookshelves of every school, art and conservation department, but most importantly on the desk of every single paintings curator – along with the second book, which is Claus Grimm’s 1978 Alte Bilderrahmen, translated as The book of picture frames [8]

Claus Grimm, Alte Bilderrahmen, 1978 https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/grimm1978/0045/image,thumbs

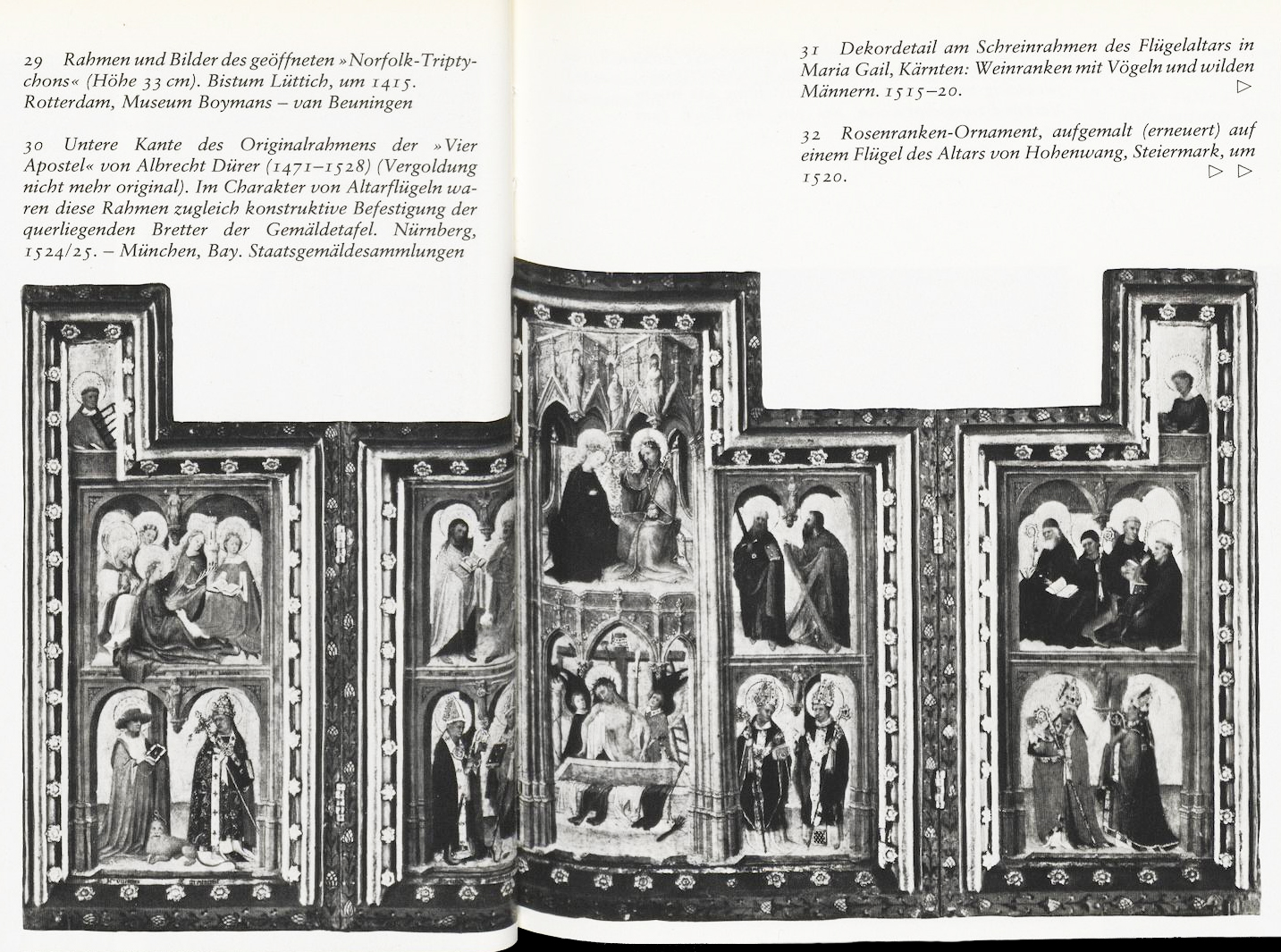

Grimm, fig. 29, The Norfolk Triptych

Liège School, The Norfolk Triptych, c.1415, o/panel, 33.1 cm. high, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen

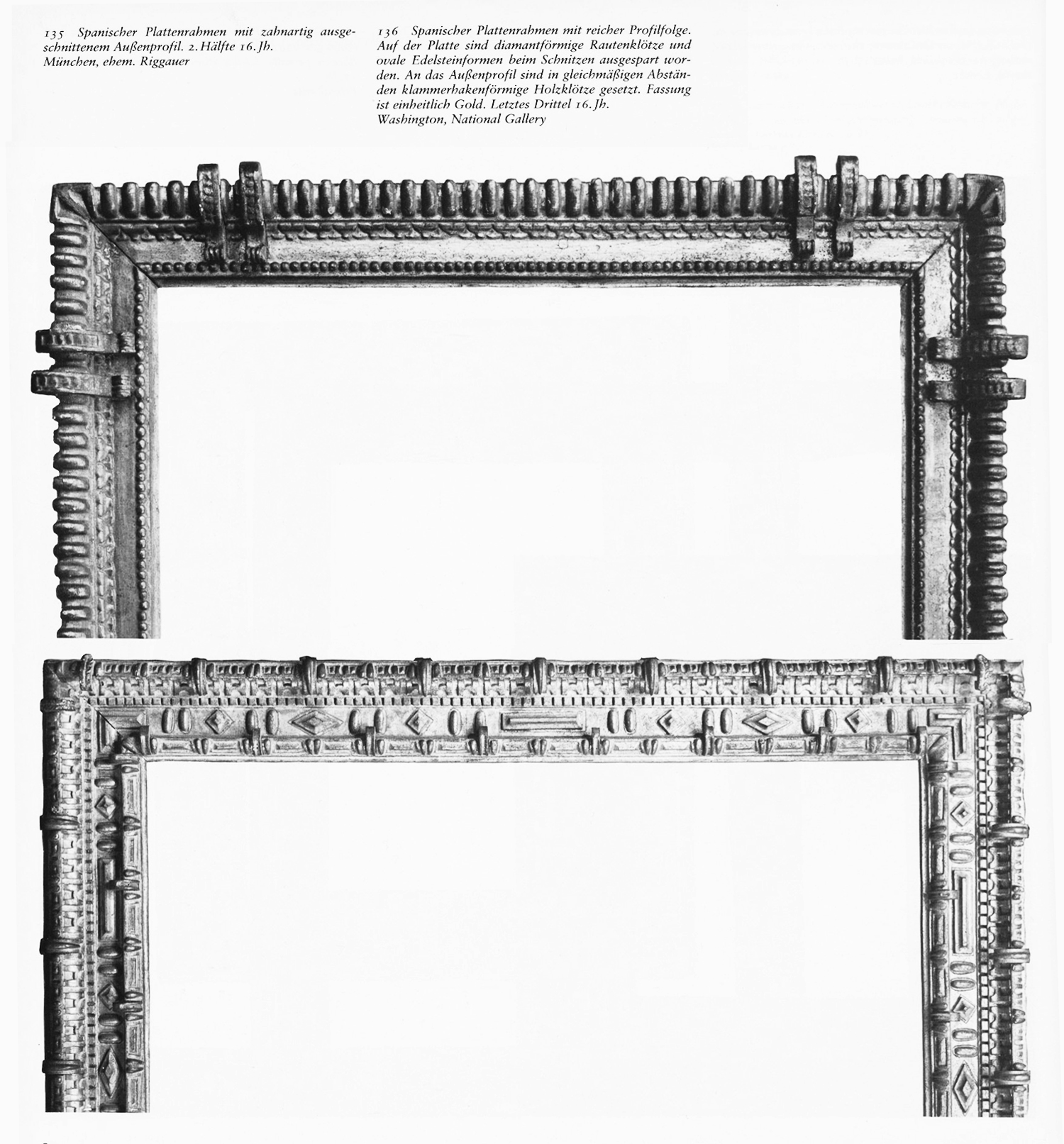

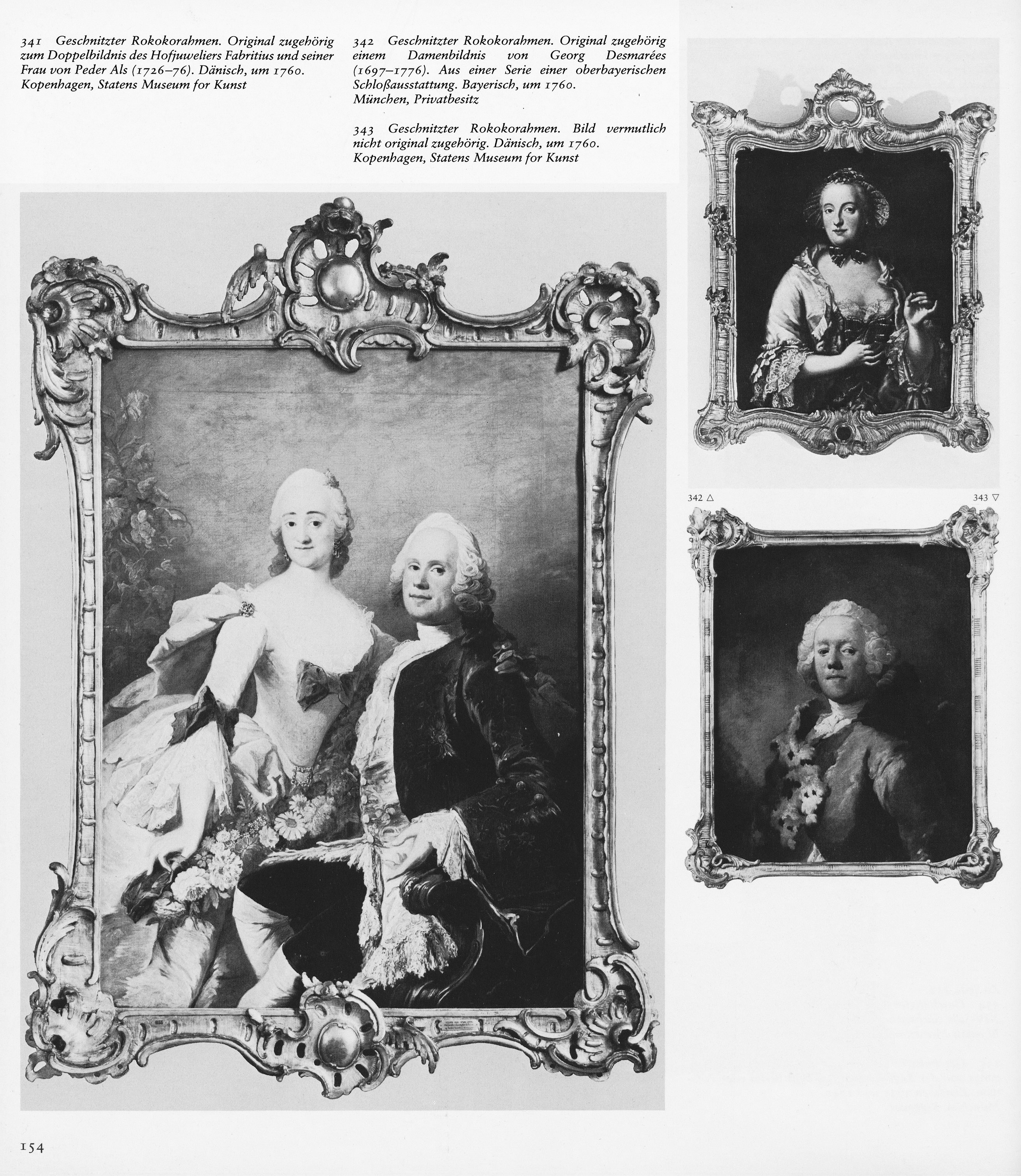

Grimm’s book is a larger, longer, more sophisticated and complex version of Heydenryk’s, with a very useful 21-page essay, a glossary, illustrations of designs for frames, engravings of frames, frames in paintings of interiors, and frames in architect’s elevations. The main part of the book is a pictorial history divided into nationalities and styles, with brief notes in the captions; this makes it very easy to see how patterns travelled and evolved, and how they differed in various countries.

The timeline begins in the second century AD, with the gilded stucco frame from a Roman-Egyptian mummy portrait; it includes more Spanish frames, and also brings in Scandinavian frames for the first time. It’s an invaluable portmanteau of periods, styles and nationalities, providing a constant core of examples from which it is nearly always possible to discover some identifying factor for a puzzling frame.

Grimm, figs 135 & 136, Spanish ‘Herrera’ frames

Johann Liss (1597-1631), The satyr & the peasant, c.1620, NGA Washington

Grimm, figs 341-43, Scandinavian Rococo frames

Peder Als (1725-75), Christopher Fabritius & his wife, 1752, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

It is unmistakably the work of a professional academic and frame historian, and it is all the more admirable considering that it was written from a standing start by someone quite young, who absorbed years of experience in the time it took to produce the book, and who has managed to gather an extraordinary amount of information in that time.

The art of the edge: European frames 1300-1900, Richard Brettell & Steven Starling, exh. cat., 1986, Art Institute of Chicago

Ugolino da Nerio (fl.1317-39/40), Madonna & Child with saints and donor, c.1317/27, cat. no 3 in exhibition, frame engaged with the panel, gilded, polychromed and punched; Art Institute of Chicago

Titian (workshop; ), Danäe, cat. no 11 in exhibition, Florentine cassetta, second half 16th century, parcel-gilt and polychrome, Art Institute of Chicago

The art of the edge: European frames 1300-1900 is an important exhibition catalogue from the historical point of view; it covers a very useful group of more than seventy frames, and includes an illuminating essay from each of the authors. It is also notable as an exhibition assembled entirely – all 600 years of it – from the Art Institute of Chicago’s own collection. Even the recent exhibition of frames at the Louvre, although large, covered only three centuries overall.

The period from the 1970s has seen the literature open out into a colourful diversity of books and articles on the materials, makers and designers of frames, as well as surveys of smaller areas – national, style-based, or limited to more narrowly focused periods. What is needed now is for these multiplying interests to become much more essential elements in the study of the relevant art: paintings should automatically be seen in the contexts for which they were made. If the history of collecting can become, relatively quickly, a major sub-section in the history of art, how much more important should it be to look at the setting for which the artist knew he was working, either very specifically or in more general terms?

Paintings should never be seen as two-dimensional objects on the flat pages of a book; they have volume and texture, they hang on walls within a three-dimensional space, or stand on altars with buttresses supporting them; and for nearly all their millennia of history they have relied on frames to protect them, bind them to their location, isolate them from distraction, and explain them through symbol and ornament. When they are taken from their original homes to museums, they deserve to be given back some of their context – if not their first frames, then something contemporary and appropriate, as well as the odd chair, console, wall-hanging or chest. They also deserve that every curator should know something about these contexts, and it is up to all of us to make the knowledge we have available to anyone who wants, needs, and ought to learn.

*************************************************

A partial and eclectic bibliography:

Annie Ablett: ’The frame: its purpose to protect’ (two articles), The Picture Restorer, XVII Spring 2000, pp. 13-16 and XVIII Autumn 2000, pp. 9-11; ’The frame: its purpose to enhance’, The Picture Restorer, XXI Spring 2002, pp. 9-12.

Hubert Baija: ’Gilding in the Dutch Golden Age’, Painting Techniques. History, Materials and Studio Practice. Summaries of the Posters at the Dublin Congress, 7-11 September 1998, International Institute for Conservation, 1998, unpaginated

W.H. Bailey: Defining edges: A new look at picture frames, New York (Harry N. Abrams Inc), 2002, (illus.)

R. Baldi, G. Gualberto Lisini, C. Martelli & S. Martelli: La cornice fiorentina e senese: storia e tecniche di restauro, Florence, 1992

Reinier Baarsen: ’Herman Doomer, ebony worker in Amsterdam’, Burlington Magazine, CXXXVIII, 1996, pp. 739-49 (illus.)

Nancy Bell (ed.): Historic framing and presentation of watercolours, drawings and prints, Proceedings of conference held June 1996, Leigh, Worcester, Institute of Paper Conservation, 1997 (68 illus.)

Richard R. Brettell & Steven Starling: The art of the edge: European frames, 1300-1900, exh. cat., Chicago, Art Institute, 1986

Christian Burchard: ’Bilderrahmen, Sprache der Ornamente: Beispiele aus der Sammlung Pfefferle, München’, Barockberichte: Informationsblätter des Salzburger Barockmuseums zur bildenden Kunst des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts, XXIV/XXV, 1999, pp. 397-412 (illus.)

Stanley B. Burns: Forgotten marriage: The painted tintype & the decorative frame 1860-1910, New York, The Burns Press, 1995 (illus.)

Mary Bustin: ’Recalling the past: evidence for the original construction of Madonna enthroned with saints and angels by Agnolo Gaddi’, Conservation Research, 1996/1997, Studies in the History of Art, Washington, National Gallery of Art, 57, 1997, pp. 35-60 (26 illus.)

Isabelle Cahn: Cadres des peintres, exh. cat., Paris, Musée d’Orsay, 1989 (37 figs.)

Anthea Callen: ’Framing the debate’, The art of Impressionism: Painting technique & the making of modernity, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2000 ( 281 illus.)

Lorne Campbell: National Gallery Catalogues. The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish School, London, National Gallery, 1998

Peter Cannon-Brookes: ’Picture framing I: English picture frames in three London exhibitions, II: Leighton at the Royal Academy’, Museum Management and Curatorship, XV 1996, pp. 218-25 (illus.)

Peter Cannon-Brookes: ’Picture framing: A framed portrait from the Roman Empire’, Museum Management and Curatorship, XVI 1997, pp. 312-4 (illus.)

Peter Cannon-Brookes: ’Elias Ashmole, Grinling Gibbons and three picture frames’, Museum Management and Curatorship, XVIII 1999, pp.183-89 (3 figs.)

Alessandro Cecchi: ’The conservation of Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo’s altarpiece for the Cardinal of Portugal’s chapel’, Burlington Magazine, CXLI 1999, pp. 81-5 (3 illus.)

Timothy Clifford: ‘The historical approach to the display of paintings’, The International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, I, 1982

Alec Cobbe: ’The framing and restoration of the Historic Cobbe Collection’, in Clerics & Connoisseurs: The Rev. Matthew Pilkington, the Cobbe Family and the Fortunes of an Irish Art Collection through Three Centuries, ed. Alastair Laing, English Heritage, 2001, pp. 74-9 (24 illus.)

F.G. Conzen & G. Dietrich: Bilderrahmen. Stilverwendung Material, Munich, 1983

Anne Crookshank & the Knight of Glin: ’Reflections on some 18th century Dublin carvers’, in Avenues to the Past: Essays Presented to Sir Charles Brett on his 75th Year, ed. Terence Reeves-Smyth and Richard Oram Belfast, 2003 (18 illus.)

W. Ehlich: Bilderrahmen von der Antike bis zur Romantik, Dresden, 1979

English Heritage: Gilding: approaches to treatment. A joint conference of English Heritage and the United Kingdom, Institute for Conservation, 27-28 September 2000 English Heritage, 2001, 84 pp. (66 illus.)

Kevin Fahy & Andrew Simpson: Australian furniture: pictorial history and dictionary, 1788-1938, Woollahra (Casuarina Press), 1998 (illus)

David Franklin & Louis Alexander Waldman: ’Two late altarpieces by Bachiacca’, Apollo, CLIV, August 2001, pp. 30-5 (9 illus.)

S.E. Fuchs: Der Bilderrahmen, Recklinghausen, 1985 (146 illus.)

Christopher Gilbert: Pictorial dictionary of marked London furniture 1700-1840, Furniture History Society & W.S. Maney & Sons Ltd, 1996 (illus.)

Laura Houliston: ’Framemaking in Edinburgh 1790-1830′, Regional Furniture, XIII,1999 (6 illus.)

Joop M. Joosten: ’Framing Mondrian’, Unpublished paper given at the symposium, Modern Art in the Laboratory Technical Examination and Art Historical Implications, held at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., USA, 5 May 2001 (and see review in Conservation News, 76, November 2001, p. 47)

Andrea Kirsh & Rustin S. Levenson: ’Beyond the painting: On framing’, in Seeing through paintings: physical examination in art historical studies, Yale University Press, 2000, pp. 246-53 (8 illus.)

Roberto Lodi & Amedeo Montanari: Repertorio della Cornice Europea: Italia, Francia, Spagna, Paesi Bassi: Dal Secolo XV al Secolo XX, Modena (Edizioni Galleria Roberto Lodi), 2003 (830 colour illus.; 830 profile drawings)

Ian McClure: ’The framing of wooden panels’, in The Structural Conservation of Panel Paintings, ed. Kathleen Dardes and Andrea Rothe, Proceedings of a symposium at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 24-28 April 1995 Los Angeles, The Getty Conservation Institute, 1998, pp. 433-47 (illus.)

Pippa Mason: ’The framing and display of watercolours’, in Watercolours from Leeds City Art Gallery, Exh. cat., Leeds City Art Gallery, 1995, pp. 28-38 (5 illus.)

Melbourne Journal of Technical Studies in Art, vol. 1, ‘Frames’, Melbourne (University of Melbourne Conservation Service), 1999 (31 illus.) (an issue dedicated to articles on the frame; mainly Australian)

Eva Mendgen (ed.): In perfect harmony: Picture + frame 1850-1920, exh. cat., Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum Van Gogh, 1995

Paul Mitchell: ‘Italian picture frames 1500-1825: A Brief Survey’, The Journal of the Furniture History Society, xx, 1984 pp. 18-27 (30 plates)

Paul Mitchell: ‘Frames’, in Guide to the Exhibited Works in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, Caroline de Watteville, Lugano and Milan, 1989, pp. 365-71

Marilena Mosco: Antiche cornici italiane dal Cinquecento al Settecento, Exhib. cat., Tokyo, 1991; Florence, Galleria deigli Uffizi, 1991

Marilena Mosco & Edit Revai (eds): Cornici Barocche e Stampe: Restaurate dai Depositi di Palazzo Pitti, exh. cat., Florence, Palazzo Pitti, 1998

Marilena Mosco: ’Two important Crosten frames for two unpublished paintings by Bartolomeo Bimbi’, Dec Art, I March 2004, pp. 8-15 (8 illus.)

Tessa Murdoch: ’Jean, René and Thomas Pelletier, a Huguenot family of carvers and gilders in England 1682-1726′, Burlington Magazine, CXXXIX, 1997 (7 illus.)

Timothy Newbery, G. Bisacca & L. Kanter: Italian Renaissance frames, exh. cat., New York, Metropolitan Museum, 1990 (24 figs., 84 plates; downloadable pdf)

Timothy Newbery: Frames and framings in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, 2002 (37 illus.)

Geraldine Norman: ‘In the frame’, Hermitage Magazine, I, Summer 2003, pp. 8-9 (3 illus.)

Maria Letizia Papini: L’ornamento della pittura. Cornici, arredo e disposizione della Collezione Corsini di Roma nel XVIII secolo, Rome, Nuova Argos Edizioni Srl, 1998

Nicholas Penny: ’The study and imitation of old picture-frames’, Burlington Magazine, CXL, 1998, pp. 375-82 (and see letter, Burlington Magazine, CXLI, 1999, p. 354)

Nicholas Penny: The sixteenth century Italian paintings. I: Paintings from Bergamo, Brescia and Cremona, National Gallery, London, 2004 (illus.)

Christine Powell: ’Some French and English gilding techniques: The making and gilding of an 18th century English-style mirror frame with tooled gesso work’, SSCR Journal, The Quarterly News Magazine of the Scottish Society for Conservation and Restoration, IX, 1998, pp. 5-14

Revue de l’Art, no. 76, 1989 (an issue dedicated to articles on the frame)

F. Sabatelli, E. Colle & P. Zambrano: La cornice italiana dal Rinascimento al Neoclassico, Milan, 1992 (115 figs., 117 col. plates)

Christoph Schölzel: ’Der Dresdener Galerierahmen Geschichte, Technik, Restaurierung’, ZKK: Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung, XVI, 2002, pp. 104-29 (34 illus.)

Tobias Schmitz: Lexikon der europäischen Bilderrahmen, published by the author, German (ISBN 3-00-011231-6), 2003 (510 illus.)

Jacob Simon: The art of the picture frame: Artists, patrons and the framing of portraits in Britain, exh. cat., London, National Portrait Gallery, 1986

Jacob Simon: ‘The production, framing and care of English pastel portraits in the eighteenth century’, The Paper Conservator, XXII, 1998, pp. 10-20 (7 illus.)

Jacob Simon: ’Thomas Johnson’s The Life of the Author’, Furniture History Society, Furniture History, XXXIX, 2003 (13 illus.)

Joyce Hill Stoner: ’Whistler’s views on the restoration and display of his paintings’, Studies in Conservation, XLII 1997, pp. 107-14 (6 illus.)

Alfred Strange & Leo Cremer: Alte Bilderrahmen, Darmstadt, 1958 (25 illus.)

P.J. J. van Thiel & C. J. de Bruyn Kops: Prijst de Lijst, exh. cat., Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, 1984, transl. as Framing in the Golden Age, 1995 (117 illus & diagrams)

María Pía Timón Tiemblo: El marco en España: del mundo romano al inicio del modernismo, Madrid, Humanes, 2002

Joyce H. Townsend, Jacqueline Ridge & Stephen Hackney: Pre-Raphaelite painting techniques, London, Tate Publishing, 2004 (illus.)

Joyce H. Townsend (ed.): William Blake: The painter at work, London, Tate Publishing, 2003 (145 illus.)

Hélène Verougstraete-Marcq & Roger Van Schoute: Cadres et supports dans la peinture flamande aux 15e et 16e siècles, Heure-le-Romain, 1989, translated as Frames and supports in 15th and 16th century Southern Netherlandish painting , 2015 (downloadable book)

Hélène Verougstraete & Roger Van Schoute: ’The origin and significance of marbling and monochrome paint layers on frames and supports in Netherlandish painting of the 15th and 16th centuries’, in Painting techniques, history, materials and studio practice, ed. Ashok Roy & Perry Smith, International Institute for Conservation on the occasion of the Dublin Congress, September 1998, pp. 98-100

Hélène Verougstraete & Roger Van Schoute: ’Frames and supports of some Eyckian paintings’, in Investigating Jan Van Eyck, ed. Susan Foister, Sue Jones and Delphine Cool, Belgium, Turnhout, 2000, pp. 107-17 (6 illus.)

Jorgen Wadum: ‘Historical overview of panel-making techniques in the Northern countries’, in The structural conservation of panel paintings, ed. Kathleen Dardes & Andrea Rothe, Proceedings of a symposium at the J. Paul Getty Museum, 24-28 April 1995 Los Angeles, The Getty Conservation Institute, 1998, pp. 149-177 (illus)

Arthur K. Wheelock: ‘The framing of a Vermeer’, in Collected opinions: Essays on Netherlandish art in honour of Alfred Bader, ed. Volker Manuth & Axel Rüger, London, Paul Holberton Publishing, 2004, pp. 232-39

Lucy Whitaker & Jonathan Marsden: ‘Re-framing the Royal pictures: Episodes in the history of royal taste’, Apollo, CLVI, September 2002, pp. 50-56 (12 colour illus.)

Daniel Wildenstein: ’Gauguin and the modern frame’, and ‘The decorated frame’, in Gauguin: A Savage in the Making (Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings 1873-1888), Skira/Wildenstein Institute, I, 2002 (illus.)

Eli Wilner (ed.): The gilded edge: The art of the frame, San Francisco, Chronicle Books, 2000 (168 illus.)

*************************************************

A very full bibliography from 1995 to 2018 is available on the National Portrait Gallery website, ordered by nationality, with additional specialist areas

See also some book reviews on The Frame Blog, under ‘Reviews’

*************************************************

Notes

[1] Alice Martignon, ‘Michelangelo Guggenheim e le arti decorative’, Saggi e memorie di storia dell’arte, no 39, 2015, p. 54

[2] For more on Vannoni, see Karen Serres, ‘Duveen’s Italian framemaker, Ferruccio Vannoni’; see also ‘19th & 20th century Italian framemakers: articles in The Burlington Magazine’

[3] See Alison Clarke, ‘Stefano Bardini: dealer, restorer and collector of frames’

[4] Wilhelm Bode (1845-1929), ‘Bilderrahmen in Alter und Neuer Zeit /Picture frames in the past and present’, Pan, 1898, vol. IV, no 4, p. 251

[5] Ibid., p. 254

[6] For more on Wilhelm Bode’s ideas on picture frames, see Peter Schade’s introduction to and translation of another of his articles, ‘Reframing the paintings in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum with antique frames’, originally published in Amtliche Berichte Aus Den Konigl. Kunstsammlungen, XXXIII. Jahrgang, Nr.9, June 1912, Berlin

[7] There is a video on the Altarpieces for the Confrérie du Puy Notre-Dame d’Amiens here; see also ‘Serge Roche: ‘Cadres français et étrangers du XVe siècle au XVIIIe siècle – Part 1’, which covers the 16th-early 18th centuries in French frames, and ‘….Part 2’, which takes the story up to the high Rococo styles of the mid-18th century

[8] Claus Grimm’s Alte Bilderrahmen, 1978, is available on Heidelburg historic literature, and the 1981 translation, The book of picture frames, can be found on the invaluable Internet Archive