Print rooms, prints, and their printed borders

by The Frame Blog

The print room is considered in the main a very British phenomenon, which had its heyday from around the middle of the 18th to the early 19th century. It is noted, not only for its continuing appeal today, but also because it was often the creation of women, who produced arrangements which were fashionable but also very individual, and quite apart from the decorative schemes of the houses which held them. Print rooms could be ‘hung’ with engravings of any sort or genre – portraits, landscapes, religious and mythological subjects, or even caricatures; and they were usually finished with decorative borders, hangers and bows which echoed the frames of the paintings in the house beyond.

Printed frames in 15th century Italy

The use of engravings and custom-made borders to frame them dates back, however, as far as the 15th century in Italy, when – as soon as the first woodcut leapt fully-formed from the hands of the first intagliatore – it was turned into something else: either by sticking it on a wall, in a humble gesture towards a framed painting, collecting it in albums, or gluing it onto boxes, fans, screens, or pocket prayer-cards: all of which often demanded borders or frames. These items are the essence of ephemera, and, although produced in the great numbers which reproduction suddenly allowed, had inversely short lives.

Italian school, Madonna del Fuoco, c.1425 or earlier, hand-coloured woodcut, 49 x 40cm., Duomo, Forlí

One rare survival is the Madonna del Fuoco, a coloured woodcut attached to a wooden board which was apparently hung on the wall of a schoolroom in Forlí. In 1428 the school was destroyed by fire, but the image of the Madonna survived, to be moved to the cathedral and venerated (it is now somewhat over-framed). It has the reputation of being the earliest surviving woodcut; and it is structured like a contemporary altarpiece, with a central arched depiction of the Madonna and Child beneath the Crucifixion, saints and bishops arranged in the aisle-like compartments at the sides, the Annunciation in the spandrels at the top (the ‘clerestory’), and a group of saints and martyrs in the predella panel (the ‘crypt’). All the compartments are separated by drawn architectural mouldings – entablatures, pedestals and barley-sugar columns – and the friezes are decorated with faux-marbre inlaid patterns. Presumably there might originally have been an outer containing ‘moulding’, which has been lost to wear, tear and the fire. However, the remaining framing elements show that, from the very beginning, the print was considered as a full-blown painting which needed its own integral version of a border or frame, initiating a genre which could provide the humblest home, workshop or school with a complete domestic altarpiece.

Italian school, Virgin enthroned suckling her Child, surrounded by angels, c.1450, woodcut with stencil colouring, 53.6 x 41.2 cm., and detail, British Museum

Another surviving woodcut of this kind is a mid-15th century Italian Madonna and Child, now in the British Museum. It was found during a house demolition; it was apparently ‘lifted off the door of a house in Bassano, and is in fragmentary and poor condition’. The edges are naturally the most dilapidated areas of the print, but enough of the left side and left top remain to show that the woodcut was printed with an integral border decorated with a ribbon-&-stave moulding, imitating a carved wooden moulding in the same way that the picture of the Madonna inside it imitated a painted panel.

Anon. Augsburg school, St Bridget giving her rule to her order, 1480-1500, hand-coloured woodcut, centre panel, 26.5 x 19 cm., left wing, 26.5 x 9.7 cm., right wing, 26.5 x 9.5 cm., and detail, British Museum

A printed and hand-coloured German triptych of St Bridget establishing her rule creates a very satisfactory ‘frame’ from paired lines with a trompe l’oeil mitred sight edge, a round arched centre panel and pointed-arched wings created with spandrels of decorative foliate branches. This must have been preserved in an album or portfolio, but would have been intended, like the previous examples, to be fixed to a panel or wall, providing an instant framed mini-altarpiece, just over 15 inches or 38 centimetres across.

Where sacred prints emerged, profane and ornamental prints couldn’t be far behind, and – as well as being pasted or hung on the wall – they were used to decorate household items.

Baccio Baldini (attrib.; c.1436-87), A pair of dancers…border of music-making cupids, c.1465-80, engraving, 20 cm. diam., an ‘Otto print’, British Museum

The example above is one of a group of two to three dozen engravings: the so-called ‘Otto prints’, named after an 18th century collector from Leipzig, Ernst Otto, and possibly made in the workshop of Baccio Baldini [1]; which, it has been suggested, were produced to decorate gift boxes or workboxes in Renaissance Florence [2]. Many of these circular prints have self-borders – fantastic variations on the carved decoration of contemporary frames – and, in the present example, one which has a moulding linked to that of slightly later giltwood tondo frames: an imbricated fish-scale ornament on the back edge.

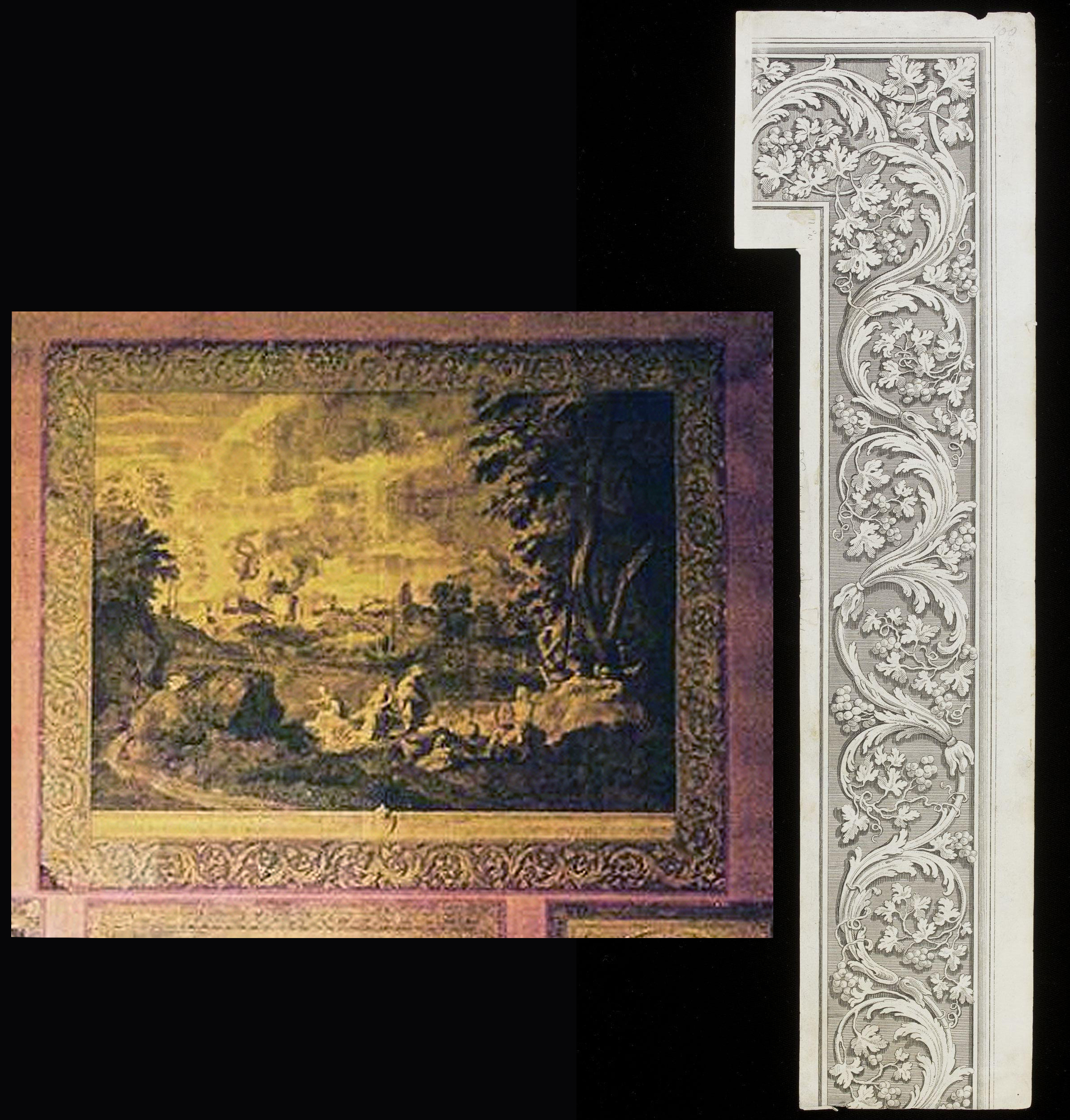

Ferrarese tondo frame, c. 1490-1520, parcel-gilt walnut, 49 cm. diam., Victoria & Albert Museum

Some of these prints may actually have been employed as patterns for carved frames, the engraved ornament being realized in finely detailed wood. In the instance above, the result (although labelled a looking-glass frame) seems to be the setting for a small devotional painting, since the scrolling acanthus on the frieze supports figures and animals symbolic of good or evil (the letters ‘BONUM’ and ‘MALUM’ are strung through the branches to left and right).

Baccio Baldini (attrib.; c.1436-87), A bear attacked by five dogs, c.1465-80, engraving, 20.5 cm. diam., an ‘Otto print’, British Museum

Others have festoons of fruit and leaves in their borders, echoing the garland frames used from c.1450 by the Della Robbia for their glazed terracotta tondi, and later by framemakers as carved giltwood settings for painted tondi. This example, above, is especially notable for the fruit and leaves which make up the garland, used in a symbolic sense for the frames of Madonna tondi, and thus indicating the possibility that the depiction of dogs attacking a bear here was a moral allegory of some kind. The integral garland frame makes it likely that prints of this kind could, as well as decorating a circular box, have been mounted onto a backing board and then hung or pinned onto a wall.

Stick-on Renaissance frames

The next stage on from these self-framed prints was the production of separate borders which could be purchased in sheets and combined in various ways with pictorial engravings.

Francesco Rosselli (c.1448-c.1513/18), The Nativity, from the series Life of the Virgin & Christ, 1470-1500, 22.2 x 16.5 cm., with a sheet of framing elements designed for this series, 29 x 22 cm., both Metropolitan Museum, New York

Francesco Rosselli (c.1448-c.1513/18), print of The Nativity montaged with four of the framing elements designed for it

The entrepreneurial Florentine engraver, Francesco Rosselli, sold series of prints (such as his Life of the Virgin and Christ in fifteen parts), with framing elements in various styles which could be cut out and pasted around the images on a backing sheet of paper or board [3]. These combined to produce rather beautiful depictions of a cassetta decorated on the lateral rails with candelabrum ornaments, and on the horizontal rails with flying cherubs. The corner cassettes contained daisy paterae, symbolic of Christ’s humility. Strategically placed thicker lines in the borders gave an impression of shadow beneath the projecting fillet ‘mouldings’ which outlined each rail, and – along with the delicate shading of the ornaments – brought depth and plasticity to the whole.

Rosselli also published a series of six prints from Petrarch’s Triumphs, with panels quoting from the poem, , and a set of twenty-four Prophets and twelve Sibyls. If all of these were available with several different borders, then a determined collector in late 15th-early 16th century Italy could easily have constructed his or her own very striking print room. The catalogue entry on one of the candelabrum panels in the British Museum notes that,

‘Other border panels by Rosselli may have been used to frame the Triumphs of Petrarch and other now lost series. The present panels or comparable, now lost, examples are recorded in two successive entries in the Rosselli inventory (1525), referring to ‘1 forma di fregio d’otone (brass), d’un foglio chomune’, and ‘1 forma di fregi di fogli chomuni, dopia’ [‘1 style of ‘brass-style’ frieze on a sheet containing several’ and ‘1 style of frieze on a sheet of several, double’].’[4]

Baccio Baldini (attrib.; c.1436-87), print of The planet Venus, montaged with ‘Baldini’ borders, from engraved sheet, 34.2 x 20.9 cm., Albertina, Vienna; from Arthur Hind, Early Italian engraving, 1938, vol. 2, plate 131

Baccio Baldini (attrib.; c.1436-87), print of The planet Venus, montaged with ‘Baldini’ borders, from engraved sheet, 34.2 x 20.9 cm., Albertina, Vienna; from Arthur Hind, Early Italian engraving, 1938, vol. 2, plate 131

Suzanne Boorsch notes the similarity of Rosselli’s surviving borders to those from the workshop which produced the ‘Otto prints’, and the hand of the engraver (or number of engravers) known under the name of the non-existent Baccio Baldini. She indicates that Rosselli’s cherubs and candelabra were probably directly derived – or ripped off, as it might be put in less elegant days – from these slightly earlier models:

‘…Francesco engraved at least some one hundred plates. He was what is known as a reproductive engraver, that is, his designs followed models – drawings or prints – created by someone other than himself…’[5]

Elements from the latter, held in the Albertina, Vienna, were montaged onto a ‘Baldini’ print and illustrated in Arthur Hind’s Early Italian engraving [6]; Hind also used the ‘frame’ made from these border panels for the frontispiece of his 1911 work, Andrea Mantegna & the Italian Pre-Raphaelite engravers, where he attributes them to ‘Maso Finiguerra, or an engraver of his school’ [7]. Interestingly, all the frieze panels and corner cassettes are edged with a leaf-tip ‘moulding’, giving the whole structure an even greater resemblance to a carved giltwood frame – further emphasized by the foliate paterae in the bottom corners.

Giovanni Andrea or Antonio da Brescia/Zoan Andrea (attrib.; fl. c.1480-1519), ‘Two upright arabesques on a dark ground. LVIII and LIX…Upright Arabesque, from a series of Twelve Arabesques, of which three are by Zoan Andrea… LX…’, from Arthur Hind, Andrea Mantegna & the Italian Pre-Raphaelite engravers, 1911, p.110

Giovanni Andrea or Antonio da Brescia/Zoan Andrea (attrib.; fl. c.1480-1519), ‘Two upright arabesques on a dark ground. LVIII and LIX…Upright Arabesque, from a series of Twelve Arabesques, of which three are by Zoan Andrea… LX…’, from Arthur Hind, Andrea Mantegna & the Italian Pre-Raphaelite engravers, 1911, p.110

Further on in the same book Hind published three more panels, two of pilasters with capitals and one of candelabrum ornament entwined in a forest of scrolling foliation, all of which he attributes to Zoan Andrea, the central one having been published in ‘a series of Twelve Arabesques’ [8]. Several variations on this panel can be found in the British Museum, as well as in the Met, New York, Musei Civici di Pavia, FAMSF, and the V & A, under the names of Giovanni Pietro da Birago (designer) or Giovanni Andrea (or ‘Zoan’ – engraver). The two examples with capitals and primitive bases suggest that these might have been borders from a set developed for ‘framing’ a domestic altarpiece, at the cheaper and more inventive end of the art market. Considering how many must have been lost of these very ephemeral and fragile objects, the existence of even a relatively small number of sheets of borders and single panels does point to a potentially large market for DIY ‘frames’ to finish off pictorial engravings for display, or for private worship.

Integral borders and naked prints

Giovanni Pietro da Birago (attrib.; fl. 1470-1513), Head of Christ, crowned with thorns, 1490-1515, engraving, 18.1 x 14.3 cm., British Museum

Of course, the DIY aspect could also be removed, as in the ‘Otto prints’, for even more trouble-free and economic collecting. This Head of Christ by Birago has an integral border allied to the separate panels of arabesque and candelabrum ornament, but hugely simplified, and arranged so that it could be the frieze of a three-dimensional cassetta decorated in sgraffito or mordant gilding against a black or dark blue ground. A Christ with its own frame – one purchase, unlike the prints with extra sheets of border elements – can be imagined as glued to the walls of little shops, taverns, shrines, and temporary market stalls, as well as inside carriages, servants’ quarters, the smallest of religious houses, and the poorest of homes. In a slightly more affluent arrangement, it can also be imagined as accompanied by other self-bordered prints, of the Madonna, saints, etc., bringing the possibility of an embryonic and basic ‘print room’ available to nearly everyone.

French coffret housing print, anon. French School, The Nativity, c. 1490, hand-coloured woodcut, workshop of the Master of the Very Small Hours of Anne of Brittany, c.1490, hand-coloured woodcut, 23.1 x 16.4 cm., in coffret, 33 x 22 x 15 cm., Art Institute of Chicago

French coffret housing print, anon. French School, Christ as the Man of Sorrows, c. 1500, hand-coloured woodcut, 22.5 x 14.5 cm., in coffret, 23.5 x 16 x 10 cm., National Gallery of Art, Washington

Other examples of engravings used as an affordable means of decorating the home include their application to the surface or interior of objects. There do not seem to be many survivals of the ‘Otto prints’ actually fixed to the tops of gift or work boxes; however, the use of woodcuts to decorate the inside of boxes and caskets has survived in a small number of late 15th-early 16th century French coffrets, which have hand-coloured woodcuts (here, of the Nativity and Christ as the Man of Sorrows) glued onto the undersides of their lids. The first print just has a simple drawn border, but the Christ has a cartouche at the top, inscribed ‘Ecce Homo’; it is set in ornamental spandrels, and the whole print is further ‘framed’ (in both cases) by the rim of the lid.

These coffrets are mysterious in their function, possibly having been used as portable shrines, along with relics of saints, small testaments or Books of Hours, or even the Host. They may have been cash boxes, with a holy print to guard them, intercede for good fortune, or avert miserliness in their owners; however, their proportions seem to make it most likely that they were book boxes [9].

Petrus Christus (fl. 1444-1475/76), Portrait of a female donor, c.1455, o/panel, 16 7/16 x 8 ½ ins (41.8 x 21.6 cm.), and detail, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Joos van Cleve (c.1485-1540/41), The Annunciation, o/panel, 34 x 31 ½ ins (86.4 x 80 cm.), and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

There are various depictions of interiors where prints have been fastened to the wall; this is usually done quite casually, in contrast to the examples mentioned above – the woodcuts of the Madonna, stuck to panels or doors, and rescued from the house in Bassano and the Forlí schoolroom; the engravings (single or in series, and also mounted on panel or card) given purpose-made borders; the Head of Christ with its own integral frame. Instead, engravings and woodcuts displayed in rooms are nearly always represented as borderless, and pinned or stuck to the wall, often so badly that their edges billow up or their corners curl: although this is a convention, allowing us to see the object for what it is – a thin and ephemeral paper print familiar to anyone looking at the painting. Like the two examples above, this may be because the painting in question is nearly always a sacred image, and a simple coloured woodcut of Moses pinned to the Virgin’s wall in an Annunciation offers even the poorest worshipper a jolt of recognition. Similarly, the right-hand donor wing of Petrus Christus’s altarpiece (the centre panel is missing) has a print of St Elizabeth stuck to the wall with red sealing wax, giving the wealthy young woman in fashionable velvets, with a Book of Hours, prie-dieu and arcaded window, some common ground with a humbler spectator [10].

The beginnings of the British print room

William Humphrey (1740-c.95), after George Vertue, George Vertue & Margaret his Wife, in the very Habits they were Married: Feby 17th Anno Domini 1720, 1765-1810, etching, 36.8 x 43.4 cm., from the 1720 drawing, British Museum

During the 16th century and 17th centuries, prints seem all but to have vanished into the albums and portfolios of collectors, and there are fewer sightings of them in pictures, painted on the walls of interiors. They emerge again in the 18th century, when they were hung both framed and unframed in collectors’ houses. As Susan Lambert reports,

‘The engraver and historian, George Vertue, chose to commemorate his marriage by depicting himself and his wife in front of a display of “heads” arranged to complement the rhythm of the panelling on which they were hung, thus placing his partnership in a lineage.’ [11]

The ‘heads’ are those portrait engravings of illustrious figures in faux stone integral frames, often with trophies comprising objects associated with them on the pedestal beneath and in front of the portrait itself. These had developed in Italy in the 16th century from the small framed drawings of artists which Vasari (1511-74) incorporated in the elaborate mounts which held the drawings he collected, in his album, Il Libro dei disegni.

Cristofor Chrieger after Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, from Le vite de’piu eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori, 1568, woodcut, 13 x 11 cm., Royal Academy, London

When he published his monumental work, Le vite… (The lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors & architects), each life was illustrated by the engraved portrait of the relevant artist, set in one of a small number of varied frames. Each frame was given the attributes of the appropriate branch of the arts. From this beginning, the frontispieces of a great number of books came to use a similar ‘framed’ portrait of the author [12]; and single prints of the great and good were adapted from painted portraits into the same style of presentation. The latter were particular popular in the Netherlands and Germany [13] during the end of the 16th and the 17th centuries, helping to spread the fashion for Auricular frames.

William Humphrey after George Vertue, George Vertue & Margaret his Wife…, from the 1720 drawing, with (left) Vertue after Kneller, The Hon. Robert Price, Esq., 1715, engraving, 37.5 x 26.8 cm., and (right) Vertue after John Taylor (?), William Shakespeare, 1719, etching & engraving, 36.2 x 24.3 cm., all British Museum

This sort of thing, therefore, is what we see in the background of George Vertue’s drawing of himself and his wife (in the later engraving by Humphrey). Between Vertue and Margaret is the portrait of a chap in a long pale wig, framed in an oval or tondo, with a coat of arms at the base and a shaped plinth: for example, Vertue’s own engraving after Godfrey Kneller of the Hon. Robert Price. To the right of Margaret is another print, this time of a chap with short dark hair, an oval frame with a scroll slung across the top, and a very small coat of arms at the bottom: for example, Vertue’s engraving after John Taylor (?) of Shakespeare. Both, like the other portraits on the wall, are held in very simple architrave frames – probably painted black and polished – and arranged in a pattern with much smaller miniatures, the hangers of which are emphasized with enlarged rings and decorative bows. Here, in the room of Vertue, an artist and engraver, we can see a version of the print room emerging again, on its way from its early Italian roots to its fashionable mid-18th century apotheosis.

Pietro Fabris (fl. 1768-78), Kenneth Mackenzie, 1st Earl of Seaforth, at home in Naples, 1771, o/c, 35.5 x 47.6 cm., Scottish National Portrait Gallery

A much later stage in the use of prints in a hang of framed pictures is depicted in Pietro Fabris’s painting of Lord Fortrose, later the Earl of Seaforth, in his apartment in Naples. A hang of mixed oil paintings, watercolours, pastels and drawings has been arranged symmetrically on the panelled wall above and behind the chimneypiece with its Rococo looking-glass. They are all close-framed alike, whatever their medium, so that the only pieces with what a later age would consider as the mounts necessary for anything not an oil painting are the unframed prints, with their wide margins of blank paper, pinned on the wall behind the framed sanguine drawings. Unlike fragile pastels, drawings and watercolours, which needed glazing to protect them, prints must have been considered less delicate, and were also cheaper, so continued to be displayed unframed as much as framed.

They could also be varnished, allowing them to be somewhat protected whilst still being unframed – or framed without glazing. The diarist, Samuel Pepys, was noted for his collection of prints, that part of which was stored in albums still remaining with the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge:

‘The diary and correspondence show that Pepys began collecting print portraits quite early on…

From an early stage he also bought a large number of topographical prints and ‘holy pictures’, many of which were intended to be framed and hung. These prints – a “crucifix”, “Santa Clara’s head”, portraits by Nantreuil, topographical scenes, etc., – were varnished, pasted onto board, and put into gilded or black frames. However, none of the many framed prints which Pepys owned has been preserved. Just after hanging up a new print he writes in his diary “and now my closet is so full stored and so fine as I would never desire to have it better”.’ [14]

His ‘closet’ was evidently a small print room in itself, where the engravings were framed but not glazed; they were also professionally varnished:

‘This morning comes Mr Lovett and brings me my print of the Passion, varnished by him, and the frame black; which endeed is very fine…

…And so to the office, there to set up again my frames about my Platts [engravings or maps], which I have got to be all gilded, and look very fine.’[15]

Unknown artist, Samuel Pepys’s library in c.1693, drawing, Magdalene College, Cambridge

His maps were of course also engravings, also varnished, and were mostly hung in traditional manner, as can be seen at the extreme left in the drawing of Pepys’s library – stretched between a rod at top and bottom, with a cord at each end depending from hooks adorned (in this case) with bows. Maps hung in just this way, although without the decorative bows, are depicted in scores of 17th century Netherlandish interiors.

Hannah Woolley, A supplement to the queen-like closet, 1674, pp. 70-71

In 1674, eight years after Pepys filled up his closet with prints, Hannah Woolley was publishing the first blast of a call to arms for all women, with her instructions for making a print room of one’s own – the sort which is commonly thought of today almost as an archetypal print room:

‘To adorn a Room with Prints.

Buy of your Prints only Black and White, of sorts what are good, and cut them very exactly with a small pair of Cissers from the paper, put them into a Book as you do cut them; then let your Room be done with plain Deal, but Wainscot fashion [i.e. panelled in pine], and let it be painted all over with White-lead and Linseed-Oil, ground together, and some little streaks imitating Marble: then lay your Prints upon a smooth-board with the wrong-sides upwards; then with a knife take some Gum-Dragon, steeped well in fair water, spread them all over as thin as you can, and still as you do them, take them up with your knife, and so turn them into your hand, and clap them upon the Wainscot; but let it be dry first; close them well on with your fingers that they be not hollow in any place; and observe to put them in proper places, or else it will be ridiculous; be sure to put the things flying above, and the walking and creeping things below; let the Houses and Trees be set sensibly, as also Water with Ships sailing, as you put them on, observe that they have a relation one to another.

…you may make fine stories… any thing you can imagine, for there is not any to be named, but you may find it in Prints, if you go to a Shop that is well stored… it makes a Room very lightsome as well as fine: as for those in Colours I do not esteem for this purpose, for they look Childishly, and too gay.’ [16]

The only difference from the kind of print room which has survived from the second half of the 18th century was that Hannah Woolley’s recipe treated her materials more like the pictorial elements of a toile de jouy, where the images were cut completely out of the paper and islanded on the faux-marbre ground of the panelling; no borders seem to have been involved. Perhaps lots of little closets were decorated in this way, although unluckily none of them remain [17]; they were probably seen as ephemeral crazes, easily discardable.

The flowering of the print room in the 18th century

Because none of them has survived, there is no direct line from rooms decorated under Hannah Woolley’s influence to the 18th century rooms which are left to us, although it is possible to take issue with Anna O’Reagan’s statement that the latter belong to a ‘short-lived trend’ [18], given that it can be seen as a trend dating back, even beyond the queen-like closet, to 15th century Italy. The earliest of the 18th century rooms still extant may be the one at Petworth, created at some point between 1749 and 1764; otherwise it is Castletown House in Co. Kildare, which was planned in the early 1760s and finished in 1769. The latest is at Calke Abbey, where some prints date from 1814, giving a rough life (in several episodes) of 400 years for ‘framed’ prints stuck onto walls, or 350 years for groups of prints with separate borders.

The fashion must have been relatively well-established even by the earliest date for the Petworth room, since Mrs Delany (1700-88) was taking part in print room activities in 1750-51 in and around her home in Ireland. In 1750 she visited her friends the Veseys, who lived at Lucan Castle, outside Dublin (replaced, sadly, in 1772 – print room and all – by a Palladian-style mansion), a visit she described in a letter to her sister, Mrs Dewes:

‘On Monday, Mrs. F. Hamilton, Bushe, D.D. and I went to breakfast at Lucan, left this at half an hour after 7…

…breakfast prepared for us in Mrs. Vesey’s dairy, and the table strewed with roses ; just as we were in the midst of our repast came in Lady Caroline Fox, Mr. Fox, Mrs. Sandford, and Master Fox…Mr. Fox is a sensible, agreeable man. Lady C. F. humdrum. It rained furiously ; so we fell to work making frames for prints.’ [19]

By the following spring she had evidently started on her own print room, at Delville, her husband’s villa, much nearer Dublin, as she had commissioned her brother to send her some borders for edging them from London [20].

Lady Llanover, The autobiography and correspondence of … Mrs. Delany, 11 April 1751, pp. 34-35

This argues a trade in borders which was already well-established in England, even if not yet in Ireland, before the middle of the century. By 1753 Mrs Delany’s friend, Horace Walpole (1717-97), had created his own print rooms at Strawberry Hill, and was announcing them in a letter to his friend, Sir Horace Mann; he also ascribed the fashion to the person he thought of as its inventor:

‘Now you shall walk into the house. The bow-window below leads into a little parlour hung with a stone-colour Gothic paper and Jackson’s Venetian prints, which I could never endure while they pretended, infamous as they are, to be after Titian etc… From hence, under two gloomy arches, you come to the hall and staircase, which it is impossible to describe to you, as it is the most particular and chief beauty of the castle… The room on the ground floor nearest to you is a bedchamber, hung with yellow paper and prints, framed in a new manner invented by Lord Cardigan; that is, with black and white borders printed. Over this is Mr Chute’s bedchamber, hung with red in the same manner.’ [21]

Montage of Chinese paintings & woodblock prints, c.1740-55, bordered with a printed black fret on a green ground, in the Study, Saltram, Devon NT

It has been suggested that this mention of the 4th Earl of Cardigan, otherwise the 1st Duke of Montagu (2nd creation; 1712-90), refers to a scheme executed by the carver and furniture maker Benjamin Goodison (c.1700-67) in 1742, consisting of eighty-eight ‘Indian pictures’ glued to the walls of a dining-room for Lady Cardigan [22]. The hanging, above, at Saltram, has been compared to this vanished scheme of the Cardigans; it has applied rudimentary borders printed in black on green with a Greek fret. These look far too unsophisticated for the type of thing employed by Mrs Delany and her friends, and by Walpole.

After the Goodison scheme, Mrs Vesey’s and Mrs Delany’s print rooms in Ireland, and Walpole’s in Richmond, all of which have vanished, the earliest print room – one which survives – is probably that at Petworth in West Sussex, which has been extensively documented by Esther Chadwick [23]. It was made some time before 1764 and after 1749, circumscribed by two posthumous inventories, and was created in small closet off one of the bedrooms.

East wall of the Print Closet, Petworth (photo: Alexey Moskvin) showing the engraving by Lepicié after Chardin of The young schoolmistress, 1740, with corner detail (photo: Tom St Aubyn)

Seen in close up, as the Mellon Centre has so gloriously allowed visitors to the Petworth section of Art & the country house to do (there is an illustrated catalogue of all the prints in the closet), it becomes clear how fully developed the engraved borders could be, and how closely it was possible to make a printed moulding resemble a picture frame. Some of the lengths must have been printed to allow for differences of shading on the lateral and horizontal rails – probably with two or four variations per page; and, as in the Chardin above, with meticulously drawn architectural ornaments: egg-&-dart at the back edge, plain profile moulding with a frieze, and an acanthus-&-flower sprig enriched flute at the sight edge. The combination, with shading suggesting the fall of light, is very convincing, and must have been striking when the prints were clean, new and black-&-white; before time discoloured them and the pasted corners and infills began to peel away.

Examples of the Petworth ‘frames’ made from combinations of four mouldings

However, relatively few different designs were purchased for this print room; its frames use the egg-&-dart, a frieze with plain mouldings, and the enriched fluting as individual frames by themselves, or in various combinations of twos and threes. There is the additional enrichment of a small bunched leaf moulding, again used by itself or added to one of the other three . Even the lunette form of e.g. the print after Pietro da Cortona’s Scipio Africanus enthroned is given a curved frame of the same egg-&-dart moulding by cutting and joining short lengths on the wider curves, and by careful snipping of the inside edge of the border, to pleat an arc on the sharper curves. The detail on the right, where the fluted ornament is peeling away, shows how each frame was built up from the various combinations available.

Houbraken after Van Dyck, Percy, Earl of Northumberland, engraving, 1743-52

The engraved portraits in their oval faux stone integral frames, with ribbons, festoons, plinths and rocailles, have been allowed to keep as much of that decoration as will fit as spandrels inside a DIY linear border. Close to, in the catalogued images, the excision of much of their outer composition appears unsettling; but since these particular prints are all skied, it doesn’t disrupt their effect on the walls. However, Esther Chadwick does remark on the strange decision to cut the integral linear frames off five engravings by Gribelin after Tintoretto and Veronese. The originals were trompe l’oeil Baroque panel frames, with scrolling foliate and fleur-de-lys corners, and centres with the English rose and Scottish thistle , but they all ended up with the enriched fluted border. The minimal pool of ‘mouldings’, with its small family of related combinations, was obviously part of the overall effect; anything which interfered with this was rooted out, however abruptly.

West wall of the Print Closet, Petworth (photo: Alexey Moskvin) showing the engraving by Van der Gucht & Chéron of Hercules fighting the Amazons, c.1725-32, and Le Bas after Teniers, Jeu de Boule, 1742, with corner details (photo: Tom St Aubyn)

The gallery of framed reproductions has no additional frills, such as hangers, hanging bows, or related festoons of flowers; however, the ‘paintings’ are interspersed with prints of sculptures, etc., completely cut out from their backgrounds – just as Hannah Woolley advised for her 1674 print room. The linear works are also varied with the lunettes already mentioned, and with roundels, some of which seem to have been rather approximately framed. The emphasis seems to be on the effect of a mini-museum and its contents, rationally and symmetrically arranged, rather than on the decorativeness of the presentation. Stella Tillyard notes that:

‘Gentlemen coming into their property often had a closet with engravings picked up on the Grand Tour: a reminder of their youthful adventures and an advertisement of their completed education and supposed learning.’ [24]

Esther Chadwick similarly indicates that this may be a ‘male’ assemblage:

‘Some items in the Print Closet at Petworth… were clearly chosen for their personal connection to the second Earl of Egremont… do these allusions to Charles Wyndham’s family and land suggest that he was the driving force behind the room’s creation?… there is no denying that the sum of the Print Room’s parts seems to point firmly in his direction. His active collection of prints is also well documented in this period.’ [25]

However, she also points out that he was too busy and too often away to be a convincing découpeur and sticker-on of trifles, and instead suggests his wife, the Countess of Egremont (1729-94) – possibly as a memorial to him after his death in 1763. It seems equally possible, however, that the countess might have done the actual cutting-out and pasting-on of the prints and borders from a collection put together by her husband in his last decade, carrying out a programmed ‘hang’ which he might have mapped for her. The nuts and bolts of the process would have allowed for a woman in long skirts to have executed what appears to be a job for someone going up and down a ladder:

‘The prints are pasted to sheets of heavy paper that have been painted yellow, and mounted on a hessian backing stretched on moulded wooden panelling that was originally designed c.1690 to contain tapestries.’ [26]

The few variations of border, lack of festoons and hangers, does seem to indicate a male, rather than a female, sensibility, and its extreme opposite appears in the print room at Castletown House.

Chimneypiece wall of the Print Room, Castletown House, Kildare. Photo: with thanks to Steve Shriver

The humdrum Lady Caroline Fox (who breakfasted at Mrs Vesey’s with Mrs Delany and then helped cut out frames for prints while it rained) was the married incarnation of Caroline Lennox, one of the five daughters of the 2nd Duke of Richmond. One of her sisters, Emily, married James Fitzgerald, Earl of Kildare and later 1st Duke of Leinster, and made her own print room at Carton House, Kildare [27], and another sister, Louisa, married Thomas Conolly of Kildare, and was responsible for the print room at Castletown House:

‘The print-room was assembled by pasting prints on to cream-painted wallpaper, surrounding them with elaborate frames with bows and swags cut from printed sheets and then hanging whole sections on to the walls…

…Louisa’s print-room satisfied her immoderate desire for swagging… and her pleasure in planning, ordering and balancing.’ [28]

Print Room, Castletown House, Kildare, showing the extravagant frame and hanging bows on William Woollett’s print, 1761, after Richard Wilson’s The destruction of Niobe’s children, 1760, and some of the exuberant floral festoons

Here, there are innumerable different borders, and practically every picture has its bunch of ribbons, chains, or lion’s head hook, or pendant husks, whilst around them festoons and drops of flowers depend from further bows and lions’ heads. The result would probably have driven the Egremonts from the room, but the symmetry of the arrangements and the rhythmic curves of the festoons give an overall effect of animation and great charm.

Print Room, Castletown House, Kildare

It is quite a large room, when compared with the small closets which were often remade as print rooms, and was – also uncharacteristically – relatively full of traffic, being

‘…the antechamber to the state bedroom where “Speaker” Conolly held morning levees in royal fashion.’[29]

Louisa’s family were drawn in to supplying her with engravings, and Stella Tillyard quotes from her account books, as well as her letters, to document the progress of the print room:

‘Prints were sold either individually or in packets of four, six, ten or more. In 1766 [Louisa] wrote to Sarah [another Lennox sister]: “any time that you chance to go into a print shop, I should be obliged to you if you would buy me five or six large prints. There are some of Teniers, engraved by Le Bas [and used by the Egremonts at Petworth], which, I am told are larger than the common size. If you meet with any, pray send a few.” …Print rooms were sufficiently numerous for printers to produce pattern sheets from which borders were cut out and assembled.’

Louise’s nephew, son of the sister Emily who was making a print room at Carton House, sent her prints from Rome, while she herself ‘Paid Mr Bushell for prints, £1: 2: 2 ½’ in 1766 [30]. Such payments presumably also included the sheets and packets of borders, corners, and the associated ornaments.

Robert Strange’s print after Poussin, The judgement of Hercules, Print Room, Castletown House, Kildare

Print after Guido Reni, The abduction of Helen, Print Room, Castletown House, Kildare

Robert Strange’s print, 1755, after Andrea Sacchi, Marcantonio Pasqualini crowned by Apollo, 1641, Print Room, Castletown House, Kildare

There must have been – unlike at Petworth – a great many of these accessories purchased, since the Castleworth ‘frames’ are very imaginative and varied. Like the Petworth borders, they were built up by assembling several mouldings side by side, or by adding a run of ornament to a plain frieze – there was just much more choice for Louisa in getting the results she wanted. And unlike the Petworth borders, there were lots of additional elements; so that a frame could be enriched further by pasting decorative corners over a simple mitre, or by being ‘hung’ from chains, large ornamental rings or bows of cord or ribbon. The final designs had very little to do with the nationality and period of the picture behind the print; but then 18th century collectors weren’t generally concerned with the style of the original frame when they added another painting to their galleries. Sometimes there might be a contemporary giltwood frame which survived to accompany its painting, and occasionally Louisa’s inventions similarly coincided, fortuitously, with the right style for her print – for example, the Baroque pattern, above, on Robert Strange’s print after Andrea Sacchi [31], achieved by the addition of several borders.

Print Room, Rokeby Park, Barnard Castle, Yorkshire, showing half the print by Baudet, 1701, after Poussin, Landscape with Diogenes, c.1647 (top left), Baudet, c.1701, after Poussin, The effects of terror, c.1648 (top centre), and Baudet, 1701, after Poussin, Landscape with Orpheus & Eurydice, 1648 (top right). Photo: Ed Kluz

Other surviving print rooms can be found, for instance at Rokeby Park in the North Riding of Yorkshire, where the second owner, John Sawrey Morritt, created (or his wife, Ann Morritt, created) a print room between 1769 and 1791. Like the borders of the prints in Castletown, the applied frames here are more interesting and less programmatic than at Petworth; they are also more like real giltwood frames – less fantastic and befurbelow’d than Louisa, Lady Conolly’s constructions. The backgrounds of the portrait prints have been respected, and borders added around the limit of the plate, and in many cases the inscribed margin at the bottom of the printed image has been left visible. The prints are placed very close to each other in this arrangement – rather like the fashion for hanging exhibitions in the newly-founded Royal Academy – and there are no signs of trompe l’oeil hangers or chains.

Corner of print, border, and painted ‘shadow’, with canvas sub-structure, Rokeby Park. Photo: Anna O’Reagan

Anna O’Reagan’s article on the conservation of print rooms includes the close-up illustration of a corner of a print at Rokeby Park [32], showing the ground layer of painted paper and the supporting canvas beneath it; the print pasted on top, and the border glued on top of that. The border in this case is a very slender bunched oak-leaf design between two tiny bands of fluting, one of which is covered along the bottom by a stripe of maroon paint which simulates the shadow of a three-dimensional frame. In the photo of a corner of the print room, this stripe gives a ghostly roseate halo to every print, as though the painter had no idea how a real shadow would fall; however, it shows a desire to bring the ‘hang’ of prints as close as possible to a hang of real paintings – following the investment in more frame-like borders with a further trompe l’oeil detail.

Print Room, Ston Easton Park, Somerset, showing two large prints by Nicolas Dorigny after Raphael’s Transfiguration (top, at the extreme left, and bottom, towards the centre, by the lamp), and Daniele da Volterra’s Descent from the Cross (top, left of the grandfather clock, and bottom, on the extreme right)

There is a print room at Ston Easton Park (between Midsomer Norton and the Mendips), but with no apparent record of when it was created (possibly in the 1770s?). Here there seems to have been a sensibility at work rather similar to that at Petworth, with what might be thought of as masculine, classical works (rather than domestic subjects, the theatre, etc.) – classical buildings, sparse portrait engravings (including Raphael’s self-portrait), and the large sacred prints (32 x 21 inches) by Dorigny.

The spaces between are filled with patterns of miniature engravings ‘hung’ from networks of chains, cut-out urns along the dado rail, and very small festoons and drops, arranged with restraint and symmetry. The borders are also extremely restrained, apparently consisting only of egg-&-dart mouldings. This balance and limited ornamentation may have been developed to counter the decorative structure and carving of the Palladian cupboards which punctuate the walls; in the print room at Castletown, there is little distraction from the prints themselves, and Louisa Conolly may have capitalized on the plainness of the room to run riot with the decorative elements surrounding her engravings. At Ston Easton the egg-&-dart mouldings must also have been chosen specifically to echo the egg-&-dart which outlines each contour of the cupboards – the rectilinear doors and the triangular pediments – as well as the ceiling cornice. In this way they also reflect the style of the house as a whole.

The Print Room, Uppark House, NT. Photo: CanadaDry

The print room at Uppark, like that at Petworth, uses a soft yellow paper ground. This is the original finish; like many of these schemes, the prints had been pasted onto heavy paper (sometimes on a supporting layer of canvas, as at Rokeby Park), and this support was stretched onto battens, which were then mounted on the walls. At Uppark the paper foundation had been taken down for conservation when fire devastated the building in 1989, so it was out of harm’s way and could be restored to its place after the long process of rebuilding (the architecture of the room itself had to be recreated). Allyson McDermott, the historic wallpaper expert, worked on the conservation of the prints and their backing.

Uppark is an embryonic Queen Anne house, built at the end if the 17th century, with a great hall rising from ground level to roof. The print room dates originally from after 1770, when the hall was divided horizontally: the upper level provided for a formal saloon and the print room. It was made under the ownership of Sir Matthew Fetherstonhaugh (c.1714-74) by the architect James Paine, but probably decorated by Sir Matthew’s wife, Sarah (daughter of the director of the Bank of England), who had travelled through Europe with him, buying art and furnishings.

Some of the prints may have been bought on this tour; for instance, in the view, above, the engraving second from the corner in the bottom row is by Liotard after Sebastiano Ricci, Christ and the woman of Samaria, and was one of a series of eight paintings which, like the engravings, were commissioned by Joseph Smith, the British consul in Venice. Half of another in the series, Christ and the woman who believed, can be seen at the left-hand edge of the photo. The whole collection may have been bought in Venice as a packet of prints, as they alternate along the lower tier around the room.

The Print Room, Uppark House, NT, and detail of borders. Photo: CanadaDry

The borders for all the prints, however, will have been obtained in England. They are more varied than at Ston Easton, although there seem to be no stick-on corners, and the hanging rings with twiddles are ubiquitous, save for the ovals, which are hung from ribbon bows. The frames are built up from a number of mouldings which may be part of the printed design or additional to it (there are four, in the case of the Ricci prints), and two different profiles which give the effect of a central hollow or a flat frieze. The first is shaded, and decorated with a chain effect and trefoiled leaves on a shell; the second has a guilloche of scrolling foliage enriched with classical floral paterae. There is another slender border for the ovals, and the dado rail is made up of an egg-&-dart, astragal-&-bead, and an enriched fluted pattern beneath. Hannah Woolley would have approved the composition of this room – not least because of the pots of carefully cut-out flowering plants which stand on another printed moulding, above the skirting board, respecting their natural place in the scheme of things.

The Print Room, Queen Charlotte’s Cottage, Kew, and detail showing (for example) in the centre John Goldar’s print after John Collet, The recruiting sergeant, 1769

Even royal consorts got in on the act, Queen Charlotte creating a print room in the Queen’s Cottage at Kew (from 1774). This cottage orné was built as a sophisticated summer house (possibly by Sir William Chambers [33]), for retreating and refreshment when the queen, George III and their family were walking in Kew Gardens, or visiting their exotic pets. As Kate Heard’s essay on the print room reveals, although it may originally have been designed and possibly even executed by the queen, it was remodelled in 1804-05 by her daughter, Princess Elizabeth, and the ground, originally 18th century verditer, repainted [34]. It is certainly different from the rooms previously mentioned, the prints and their ‘frames’ having been mounted individually on canvas, stretched on wooden battens, and then attached to the wall like shallow plaques.

John Goldar, 1770, after William Dawes, Statute Hall for hiring servants, exh. 1768, with border, Queen Charlotte’s Cottage

All of them have exactly the same border, only in wider or narrower versions depending upon the size of the print, and have been heavily varnished – possibly more than once – giving them an overall appearance of having been French-polished. This effect is enhanced by the borders looking very much like inlaid wood, so that the whole appearance of the prints against the walls is of nothing so much as a collection of expensive place mats. They were originally fixed directly on the walls, or onto a lining hung on the walls, as,

‘…during the recent conservation work, evidence of verditer paint and plaster was found on the back of one of the Hogarth prints… It is possible that, in 1805, the English prints were cut out of the walls, and mounted on stretchers, while the additional prints [Princess Elizabeth appears to have added a group of European engravings] were treated the same way. The mounting on canvas, therefore, may have been born of necessity rather than invention.’ [35]

As well as re-using the old prints, including those by John Collet and Hogarth which her mother had chosen, and the European prints (which may also have been recycled from another royal print room) the princess seems to have cut down some pieces, and changed their sizes and shapes [36]. This implies that the borders may not have been part of Queen Charlotte’s original arrangement, and may have been acquired by her daughter to refresh the whole scheme. The individual mounting of all the prints seems to have saved the collection, since the print room was dismantled in the 1880s-90s, and all the pieces were stored at Windsor Castle. It was rehung in 1978, and has recently been conserved against an authentically-coloured background [37].

The Print Room at Blickling Hall, Norfolk, NT, in two views

The print room at Blickling Hall must date from post-1775 (the engraving, for example, after Richard Wilson’s Caer Idris which was exhibited in 1774, was executed by Edward and Michael Angelo Rooker in 1775), and has been relentlessly photographed: the National Trust Collections site has a sort of dead-letter office of images of every single framed print in the room (52; none identified), as well as ten panels of groups of prints. However, the room itself isn’t mentioned anywhere on the website of the house, and nobody seems to have been interested enough in it to write about it, document it, or investigate it in any way whatsoever. The only text connected to the heap of images is this:

National Trust Collection, Blickling Hall, Norfolk

There is no indication as to where the ‘A’ Room might be, how many prints were in it, whether it was a second print room or the original site of the unique scheme, which may have been transplanted bodily in 1974 to the room it now occupies, or may have been there already and had its numbers supplemented. Who made it first, and when was it painted over? Which are the additional borders and bows, and how were they copied? – not digitally, in 1974, so were they photographed onto matte paper, or was a run of a border hand-drawn and then printed multiple times, or were new plates made and engravings taken? This room generates so many questions. Blickling Hall has been under the aegis of the National Trust since 1940, and yet the history of its print room – one of so very few survivals across the British Isles – seems to have been hidden under a blanket for the last eighty years.

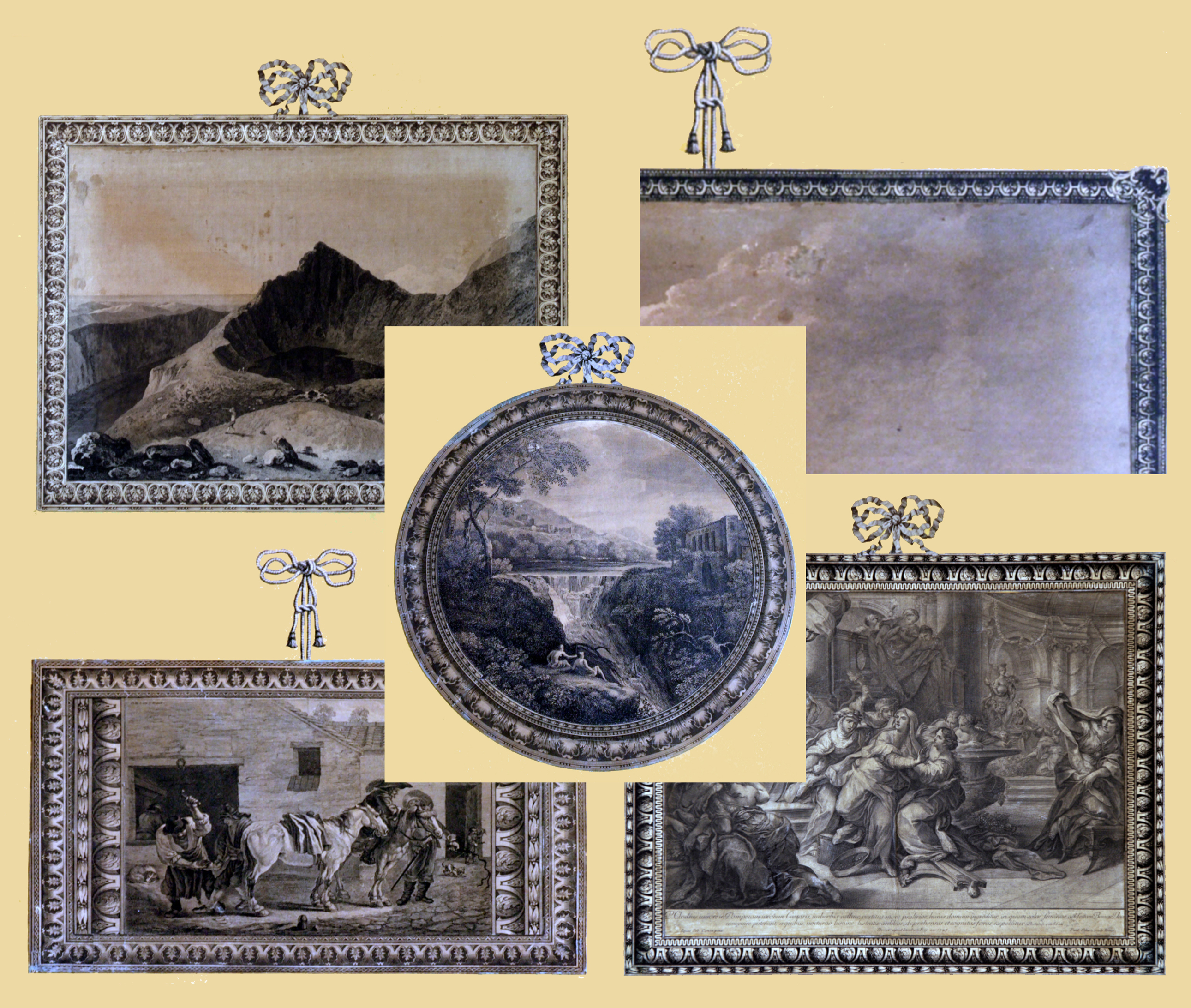

Examples of print borders on: Rooker brothers, 1775, after Wilson, Cader Idris (top left); Canot, 1775, etching after Wilson, Pontypridd Bridge, detail (top right); Pilaia, 1747, after Conca, Discovery of Clodius (bottom right); Visscher, 17th century, after Van Laer, The farrier (bottom left); Granville, 1741, after Gaspard Dughet, A waterfall (centre); Blickling Hall, NT

One of the borders, as can be seen from these details of Blickling Hall prints, is shared with Uppark House: Richard Wilson’s Cader Idris, for instance, top left, has exactly the same shaded concave profile decorated with a chain effect and trefoiled leaves on a shell, as Uppark’s eight engravings by Liotard after Sebastiano Ricci. At Uppark this border has been elaborated with two internal mouldings, a half-flower and a spiral ribbon; but in both print rooms the hollow has a top moulding of an astragal-&-triple bead, which is probably part of the border as printed.

A similar border on Blickling’s The farrier, bottom left, has a braid at the top edge and a zig-zag sight – but these details are scarcely noticeable for the fact that lengths of another border have been inserted to fill the void on the short sides between a normally-proportioned painting in landscape style, and a frame grossly extended on the horizontal axis. This helps the result to fit the wide, shallow space on the chimneypiece between Piranesi’s print of Trajan’s column, and the two oval prints of Cupid by Donato after Stefano Tofanelli; and some sort of logic is retained by the infills being the two outer ‘mouldings’ used to frame the Piranesi – a bunched bay leaf-&-berry, and an egg-&-dart, where the eggs have turned into tiny lettuces. The same frame surrounds the print of Conca’s Discovery of Clodius in the image above, bottom right.

Another border – an enriched chain pattern between two small mouldings – has been used around Wilson’s Pontyprydd Bridge, top right; and a purpose-made tondo frame, composed from short curved lengths of an acanthus-&-shell moulding, for Gaspard Dughet’s A waterfall. Although this seems a room quite simply arranged, with space between the prints and no subsidiary ornaments, the number of different of borders is greater than at Castletown, where an appearance of variety is increased by the use of festoons, drops, bows and hangers.

The Print Room at Woodhall Park, Hertfordshire; two views

A room more in the style of Castletown is the print room at Woodhall Park; in fact, it is even more hectic with images large and small, festoons, drops, pendants, hangers, tassels, urns and candlesticks – they crowd from dado rail to cornice (both marked with framing borders), and even flow along the cove of the ceiling in swoops and swerves of garlands. The house was built from 1777 to 1782 under the ownership of Sir Thomas Rumbold, a governor of Madras, and the print room installed in the latter year. It seems to have been carefully maintained through subsequent ownerships – the house was bought with all its contents in 1801 by Samuel Smith, a scion of the banking family from Nottingham [38], whose descendants still own it, although it has been let to a school for the last 90 years. This means that images are rather hard to come by, and the best source of reference for the house is an article in Country Life [39].

Elevation of the print room, Woodhall Park, s. & d. ‘R. Parker 1782’. Photo: Country Life, 18 February 2018

One of the illustrations shows what is probably the only surviving design for a professionally-installed print room in the 18th century. All the prints are numbered for identification, and each space in the design which represents a print must also represent the image overall – print plus border – since the whole has obviously been carefully measured, and is extremely close to the finished hang. This is a very rare image of an elevation for such a relatively ephemeral form of gallery. The Country Life article records the most recent restoration of rooms in the house, undertaken in 1995:

‘The first room they addressed was the Print Room. It is lined with 350 engravings framed with garlands and festoons, the pictures forming “a complete digest of the connoisseurship of the time’”, a microcosm of English Grand Tour taste, as described by Francis Russell (Country Life, October 6, 1977). The conservation work was done by Allyson McDermott, the paper and wallpaper expert.

All the prints were taken off and cleaned and remounted on Japanese lining paper and the original ground paper colour of verditer blue was reinstated. Ink and wash plans for the design survive, together with an accompanying book identifying all the subjects. This also names the obscure creator of the room, R. Parker, and the date 1782.’ [40]

Sir Oswald Birley, Mersham-le-Hatch, 1933, Lot 99; Thomas Chippendale, mahogany & fruitwood stand, 1767, made for Sir Edward Knatchbull to hold Sir Wyndham Knatchbull Wyndham’s Indian bureau, Lot 246; both Sotheby’s, 24 March 2021

A much earlier example of a professionally-installed print room (sadly, no longer surviving) was created in Mersham-le-Hatch (Hatch Park), near Ashford, Kent, where Robert Adam built his first complete house for Sir Wyndham Knatchbull Wyndham, and following the death of the latter at twenty-six in 1763, for his uncle, Sir Edward Knatchbull. By 1767 Sir Edward had called in Thomas Chippendale to furnish the house; a process which was recorded in letters and other documents over the ten years up to 1779, in which Sir Edward became tetchy over rising costs, and Chippendale became similarly tetchy over his client’s lack of appreciation for the inherent value of his own exquisite workmanship.

The print room was installed in the closet off the Alcove Bedroom, which was used as a dressing-room by Lady Knatchbull. Lindsay Boyton has published Chippendale’s detailed invoices for this and the other rooms which he decorated and furnished, as well as the written exchanges between him and Sir Edward, in Furniture History (1968) [41], which gives a good idea of the colourfulness of this particular print room.

Chippendale’s 1767 invoice for creating the print room in the ‘Closet Adjoining…the Alcove Bedchamber’ at Mersham-le-Hatch, Boynton, p. 94 [see note 41]

Verditer, that fashionable slightly greenish-blue colour, also used for the background of the print rooms in Woodhall Park and Queen Charlotte’s Cottage, was applied by hand on the thick backing paper which provided the ground for the prints; this made Sir Edward particularly fratchety:

‘As to the Man who putt up & colour’d the Green Paper he was not above two days at work, and did it extreamly bad, went away & left part of his work to be done by the other Man, with whom I find no fault, only that you charge Coach hire as well as their time in travelling which is unreasonable to charge both, for had I employed a Person in the Country who could have done everything just as well as your Men, I sho’d not have been charged a farthing for travelling or Coach hire, so I shall expect an Abatement in these Articles…’ [42]

Sir Edward presumably chose and provided the prints himself (or his wife did), as these are not charged for; but the accessories – more than four guineas’-worth of printed borders, or 506 at tuppence each, and 91 corners to stick on top of the completed frames (91…? there must have been some extras provided), as well as all the masks, satyrs, knots and vases and festoons – give a sense of some richness, in what was probably not an overly large room.

Chippendale’s 1767 invoice for furnishings in the ‘Closet Adjoining…the Alcove Bedchamber’ at Mersham-le-Hatch, Boynton, p. 92 [see note 41]

Thomas Chippendale (1718-79), ‘Chinese’ chairs, preparatory drawing for the Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director, 1753, ink & wash, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; armchair from a suite for David Garrick, 1768, painted oak, modern upholstery, Art Institute of Chicago

As it was a dressing room, it did contain, importantly, a large looking-glass over the chimneypiece and a set of armchairs, all painted to match the prevailing colour scheme [43]. These would have been something like the drawing by Chippendale, top right, but with a caned seat, a cushion, and a colour scheme like the original blue-&-white of the upholstered armchair in the bottom of the same image, which was made for David Garrick in 1768. The museum entry for the latter notes that,

‘A 1768 invoice from Chippendale to the Garricks lists “8 French Arm Chairs very neatly Carv’d & painted Blue & white … cover’d with your own Blue Damask”.’

Chippendale’s phrase to describe the colour of the chairs for Mersham in 1767 and Garrick in 1768 indicates that the furniture in Lady Knatchbull’s print room would have been of the same turquoise blue, toning happily with the verditer walls; the engravings, borders and printed ornaments would have stood out in monochrome black-&-white – not toffee-colour, as the prints in Queen Charlotte’s Cottage now appear, nor shades of sepia, like those at Woodhall Park, but fresh, fashionable, and still relatively avant-garde.

Thomas Chippendale (1718-79), ‘Frets’, Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director, 1754

One can only speculate as to whether Chippendale would have bought in all the printed borders employed at Mersham, or whether he might, for example, have adapted some of his own ‘Frets’ from the Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director, to reflect the painted ‘India Back’ chairs.

19th century survivals

The Print Room at The Vyne, Hampshire, NT; two views and details of the borders

Some later print rooms have also survived: the one at The Vyne

‘was created by Caroline Workman and her brothers in 1817 from historic prints which had been in a portfolio in the Oak Gallery… [they] are a selection of etchings, engravings, and mezzotints’ [44].

Caroline (née Wiggett) had been adopted, aged three, by the Chute family who owned The Vyne from the 17th to the mid-20th century, and may have been Jane Austen’s model for the Cinderella figure of Fanny Price in Mansfield Park [45]. The prints she used were very varied, but only a single border appears – a frieze decorated with a foliate chain containing floral paterae. There are no other ornaments – not so much as the odd hanger; so perhaps this was very much a teenage amateur endeavour (she was about 18), done as cheaply as possible, using existing prints and no added frills – the opposite of Woodhall Park and Mersham-le-Hatch.

The Print Room at Calke Abbey, Derbyshire, NT; three views

Calke Abbey, another National Trust property, has a collection of more than eleven hundred prints – in albums, folios and frames, and also pasted onto the wall of yet another print room. This one, however, is short on Piranesi’s views of classical Rome, moralizing depictions of chastity under siege, Renaissance altarpieces or landscapes illustrating the sublime. Instead, the Caricature Room is full of satirical prints, apparently slapped onto any available bits of wall, sometimes on top of each other, with little attempt at decorous arrangement; in fact, the lack of symmetry and organization expresses the sum of the whole, as well as the spirit of its parts. The only gestures towards the usual idea of a print room seem to be in the colour (verditer), and in the borders, which have been meticulously added to practically every print, whilst urns, festoons and masks have been replaced by cut-outs of small comic figures.

Calke Abbey was owned by the Harpur family from 1622 to 1985, and its contents represent the accretions of all those years; it is basically a sort of vast historic attic, for which the Caricature Room, dating from the Regency or slightly later (after 1814-15), is an appropriate symbol. It suffers from rising damp, and a dozen prints have been moved out of the room, presumably for reasons of conservation.

Daniel Thomas Egerton (1797-1842), Eccentricity (left), & Confidence (right), coloured engravings, Calke Abbey, NT. Photos: David Midgelow

Many of the borders are similar in style and colour to those in Queen Charlotte’s Cottage, with their toffee colouring and likeness to inlaid wood; they have definitely moved away from the finely-drawn black-&-white borders of the 18th century. Egerton’s Eccentricity has a spiral ribbon winding around sprigs of leaves, and could easily be a cabinetmaker’s ‘frame’: the edging to a secretaire or a table-top. Another in the same series, Confidence, has two different borders of the same type of inlaid wood /architectural ornament, with trompe l’oeil pearls at top and bottom, and, at the sides, one of those fan or shell motifs which decorate the fronts of desks and the insides of butlers’ trays.

Examples of print borders on: George Cruikshank, The advantages of travel…, Pl. 2 (top left); George Hunt, A merry Christmas… (top right); Isaac Cruikshank, A Muddy: a sketch in Bond Street (bottom right); George Cruikshank, The four Mr Prices (bottom left); and a female who is no better than she ought to be (centre); Calke Abbey, NT

Other classical, architectural mouldings include the acanthus, top left, and Vitruvian scroll, bottom right, with more naturalistic roses and convulvulus, bottom left, and a grapevine, top right. In spite of these touches of classicism, the vibrance of the borders reflects that, for the first time since the hand-painted woodcuts of the fifteenth century, coloured prints were being pasted onto the wall, and a myriad of coloured borders had been purchased to highlight them. This is an anarchic print room, by any standard, and several stages away in period, style and idea from the 18th century scheme.

Suppliers of borders in the 18th century

Like Francesco Rosselli and ‘Baccio Baldini’ in the 15th century, there were engravers, printsellers and paper merchants in 18th century Britain who realized that there was a gap in the market, and began to design and sell sheets of separate printed borders to attach to etchings and engravings.

George Bickham the Younger

Esther Chadwick, in her essay on the print room at Petworth, notes that the Earl of Egremont bought reproductions from this printmaker and publisher, amongst others, and that in 1751 Bickham

‘advertised a “Great Variety of Chinese and other Bordering for Rooms, Closets &c.” as well as “Prints of all kinds for Pannels, Ceilings &c. of the newest Fashion”. He offered “One hundred different borderings for hanging of rooms or Prints’, printed in black, at one shilling per dozen…’ [46]

George Bickham the Younger (c.1706-71) occupied premises at the Blackamoor’s Head over against Surrey Street in the Strand, c.1740-41; May’s Buildings, Covent Garden, 1741, 1745, 1749. He retired around 1767, being succeeded in that year by Thomas Butcher [47].

Thomas Bromwich

Thomas Bromwich, trade card, 1748, Heal Collection, British Museum

Thomas Bromwich (fl. 1748- d.1787) is bracketed with Thomas Chippendale as one of the ‘18th century fashionable upholsterers… [who] were selling wallpapers’, and as proprietor of a business on Ludgate Hill, London, at the Golden Lion, where ‘the poet Thomas Gray shopped for wallpapers’ [48]. Since Chippendale supplied borders for the print room at Mersham-le-Hatch, it is reasonable to assume that Bromwich was also selling a line of borders for engravings. His trade card announces that ‘Rooms, Cabins, Stair-Cases, &c. [are] Hung with Guilt Leather, or India Pictures’, and, as at Saltram, where the Chinese panels were given printed paper borders, his so-called ‘India’ pictures were almost certainly finished in the same manner.

He supplied Horace Walpole with wallpaper, and, after his firm began to trade as Bromwich, Isherwood & Bradley, was paid on 10 June 1769 for (amongst other things) ‘wallpaper and borders’ by Charles Long of Saxmundham, Suffolk – although these borders may have been printed fillets to finish panels on the walls, or to edge or create dado-rails [49].

Bromwich, Isherwood & Bradley, paid invoice sent the William Blaithwaite, Esqr, 1773-74, Fitzwilliam Museum Accessed: 2021-04-22 15:57:00

A bill sent to William Blaithwaite in 1773-74 itemizes ‘6 doz borders… ½ doz pitts borders… 4 doz borders’, of which the ‘pitts borders’ may perhaps be an abbreviation or mispelling for the borders of pictures or prints.

Matthias/ Matthew Darly

Matthew Darly, trade card for Matthias Darly, printseller, 1762-66, British Museum

Matthew Darly, trade card for M. Darly, papermakers, 1750-90, British Museum

Matthew or Matthias Darly (c.1720-80) was an extremely versatile man, who kept reinventing and extending the limits of his accomplishments and trades. An engraved advertisement for Matthew/ Matthias Darly was offered as no 107 in the 2008 catalogue of Grosvenor Prints, which describes him as ‘caricaturist, printseller and ornamental engraver’. Amongst the various objects and skills he offers in this advert are a

‘…variety of Borders and other Ornaments for Print Rooms, and stain’d borders for Embellishing Drawings for the Port-Folio’.

Matthew Darly and John Spilsbury, A new and most accurate map of the roads of England and Wales, 1752-78, etching with engraved writing on silk, 64.6 x 44.4 cm., British Museum

Sometime between 1752 and 1758 he published, in partnership with John Spilsbury, this map of England and Wales, printed on silk (of all things, like a scarf or a very large hanky), which includes three border designs on it – one floral, and one fret, which is also printed reversed. These frets can be imagined as also printed on paper, to use around engravings, and they must be just a small sample of the borders which Darly could have produced.

He occupied premises at Duke’s Court, St Martin’s Lane (1749); Northumberland Court (1753); the Acorn, facing Hungerford, Strand (1750s); the Golden Acorn, opposite Hungerford Market, Strand (1756); facing Little Suffolk Street, Hedge Lane (1757); and Acorn, Fleet Market, Ludgate (1758) [50].

Robert Sayer

Robert Sayer, frontispiece for A Catalogue of News and Useful Maps Curious and Entertaining Prints, Books of Architecture, Great Variety of Drawing Books in all the Branches of Penmanship And the best of each Kind, c.1766, etching and engraving, British Museum

Robert Sayer (1725-94) was a ‘major publisher, map- and print- seller’, who traded from premises in London, ‘near Serjeants Inn, Fleet Street’, at the Golden Buck, opposite Fetter Lane, Fleet Street; and at 53 Fleet Street ‘(a few doors east of the Golden Buck; Sayer moved there in 1760, according to Susanna Fisher, but the premises would not have been numbered until c. 1766)’ [51]. Stana Nenadic quotes from the catalogue above in an article on ‘Print collecting and popular culture in 18th century Scotland’:

‘Sets of fine prints were described by Robert Sayer in his “new and enlarged catalogue for the year 1766” as “proper to collect in the cabinets of the curious and also make furniture elegant and genteel when framed and glazed, or may be fitted up in a cheaper manner, to ornament rooms, staircases, etc, with curious borders representing frames, a fashion much in use, and produces a very agreeable effect” [52].

François Vivarès

François Vivarès (1709-80) was an engraver, printer and publisher who came to London from Geneva in 1727, and was particularly valued – both in England and France – for his engravings of landscapes. He traded from premises at the Golden Head in Great Newport Street, north-east of Leicester Square (then Leicester Fields), from 1749-71 [53].

Although landscapes may be, both then and now, what he was most noted for, there is a wonderful cache of surviving borders by Vivarès in the collection of the V & A, etched and possibly also designed by him; including a range of classical and Baroque mouldings as well as festoons and drops.

François Vivarès (1709-80), trompe l’oeil ‘convex’ borders with acanthus-&-shell, etchings, one straight, one curved, published 1760, Victoria & Albert Museum

François Vivarès, curved borders with acanthus-&-shell, published 1760, Victoria & Albert Museum; Granville, 1741, after Gaspard Dughet, A waterfall (centre); Blickling Hall, NT

Some of them may even be recognizable as framing engravings in the surviving print rooms illustrated here: above, Vivarès’s curved acanthus-&-shell ornament is almost certainly the central moulding on Dughet’s A waterfall in Blickling Hall. It has additional ornaments at the top and sight edges, but may have been purchased like this in a richer variant of the V & A border.

Baudet, 1701, after Poussin, Landscape with Orpheus & Eurydice, 1648, Print Room, 1769-91, Rokeby Park; and François Vivarès (1709-80), border with undulating & scrolling grapevine, etching, published 1750-70, Victoria & Albert Museum

Other prints with Vivarès borders may be the two engravings after Poussin visible in a corner of the Print Room at Rokeby Park. These appear to be framed in his frieze with scrolling grapevine, published between 1750 and 1770 – the Print Room having been executed between 1769 and 1791.

Laurent Cars after J-B. Greuze, Silence!, Print Room, c.1762-69, Castletown, Kildare

François Vivarès (1709-80), flower festoons with lion’s head clasp and bows, etching, published 1759, Victoria & Albert Museum

These festoons by Vivarès in the V & A do not correspond exactly with festoons on the Print Room walls at Castletown, but they are very much in the same spirit and style. Hangers, bows and lions’ heads, also with a strong flavour of Vivarès’s work, riot around the Castletown prints, and would have been freshly on the market when Lady Louisa was inciting her relatives to purchase prints for her in London. There may be many other borders and accessories, from various designers and engravers, still lurking out there to be found; a different, ephemeral, but often very beautiful kind of frame.

François Vivarès (1709-80), oval guilloche frame, with floral fronton, foliate apron, and pendant husks, Victoria & Albert Museum

**************************************************

[1] Emily Gray notes in Early Florentine engravings and the devotional print: origins and transformations c.1460, Thesis, 2012, that ‘there is no evidence in Florentine archives that a Baccio (or Bartolommeo) Baldini existed’, p. 10 and note 8

[2] See Suzanne Karr Schmidt, ‘A new Otto print’, Print Quarterly, vol.25, no 2, 2008, p. 162, after Arthur Hind, Early Italian engraving, 1938, and Adrian Randolph, Engaging symbols: Gender, politics & public art in C15 Florence, 2002

[3] See also the sheet of Rosselli’s candelabrum ornaments, with horizontal friezes of angels supporting festoons, in the Graphiques department of the Musée du Louvre (reference from Suzanne Boorsch, ‘Framed in fifteenth century Florence’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, 37, pp. 35-36)

[4] See the entry for Francesco Rosselli, decorative border panel, British Museum 1870,0625.1055. There is a hand-coloured version of the same candelabrum panel in the collection: 1938,0709.56. There is also a sheet of vertical and horizontal foliate borders in the Met. which may have been used for The Triumphs of Petrarch series (Boorsch, ibid., pp. 37-38)

[5] Suzanne Boorsch, ‘The case for Francesco Rosselli as the engraver of Berlinghieri’s Geographia’, Imago mundi, vol. 56, no 2, 2004, p. 153

[6] Boorsch, ‘Framed in 15th century Florence’, op. cit., pp. 38-39; Arthur Hind, Early Italian engraving, 1938, vol. 2, plate 131

[7] ‘Set of eight panels of ornament fitted together to form an ornamental border. Title-page border. B. XIII. 141, 73. H., A. II. 7 Vienna, Albertina. By Maso Finiguerra, or an engraver of his school. Perhaps designed to serve as a border to the series of Planets…’, Arthur Hinds, Andrea Mantegna & the Italian Pre-Raphaelite engravers, 1911, see frontispiece and List of plates

[8] Hinds, ibid.;

[9] Séverine Lepape, ‘When assembling makes sense: an example of a coffret à estampe’, Art in Print, Nov.-Dec. 2012, vol. 2, no 4, p. 10

[10] See too the Annunciation by Jacques Daret or Robert Campin, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, where the Virgin has a small borderless coloured woodcut of St Christopher stuck over her chimneypiece

[11] Susan Lambert, The image multiplied: five centuries of printed reproductions of paintings and drawings, 1987, p. 176

[12] See Lynn Shepherd, ‘Authors in the frame: “Reading” novel frontispieces in the 18th century’

[13] See Daniela Roberts, ‘German “knorpelwerk”: Auricular dissemination in prints, woodcarving, and painted wall decorations, 1620-70’

[14] Jan van der Waals, ‘The print collection of Samuel Pepys’, Print Quarterly, vol. 1, no 4, December 1984, pp. 238-39; diary quotation 16 December 1666

[15] Pepys’s diary, 1666

[16] Hannah Woolley, A supplement to the queen-like closet, 1674, pp. 70–71

[17] The queen-like closet was first published in 1670; the supplement, in 1674; and by 1684 was on its fifth edition. It was also translated into German

[18] Anna O’Reagan, ‘The conservation of 18th century print rooms: a dissertation tour’, The Icon Book & Paper Group blog, 15 October 2018

[19] Augusta Hall, Lady Llanover, The autobiography and correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs. Delany : with interesting reminiscences of King George the third and Queen Charlotte, 1862; letter no 563, Mrs Delany to Mrs Dewes, from Delville, 30 June 1750

[20] Ibid., Mrs Delany to Bernard Granville, Esq., from Delville, 11 April 1751

[21] Lea & Blanchard, eds, The Letters of Horace Walpole: Earl of Orford: Including Numerous Letters Now First Published from the Original Manuscripts, 1842, Horace Walpole to Sir Horace Mann, from Strawberry Hill, 12 June 1753