A summary of frame exhibitions

2025 is the year for exhibitions of picture frames. From being an extremely rare and exotic beast, we are beginning to see displays of frames pop up ever more frequently around the world, as museums awake to an under-appreciated area of their collections. As an introduction to these, here is as comprehensive as possible a guide to frame exhibitions in the 20th and first twenty-four years of the 21st century (please excuse any omissions).

Frame exhibitions in the 20th century

Almost a third of the way through the 20th century, an unexpectedly wide-ranging and imaginative exhibition was mounted in Paris, which might have caused dealers, collectors and restorers of frames, not to mention carvers and gilders, to imagine that their subject had at last achieved recognition, and that antique frames would no longer be prey to banishment, violent alteration, or simple neglect.

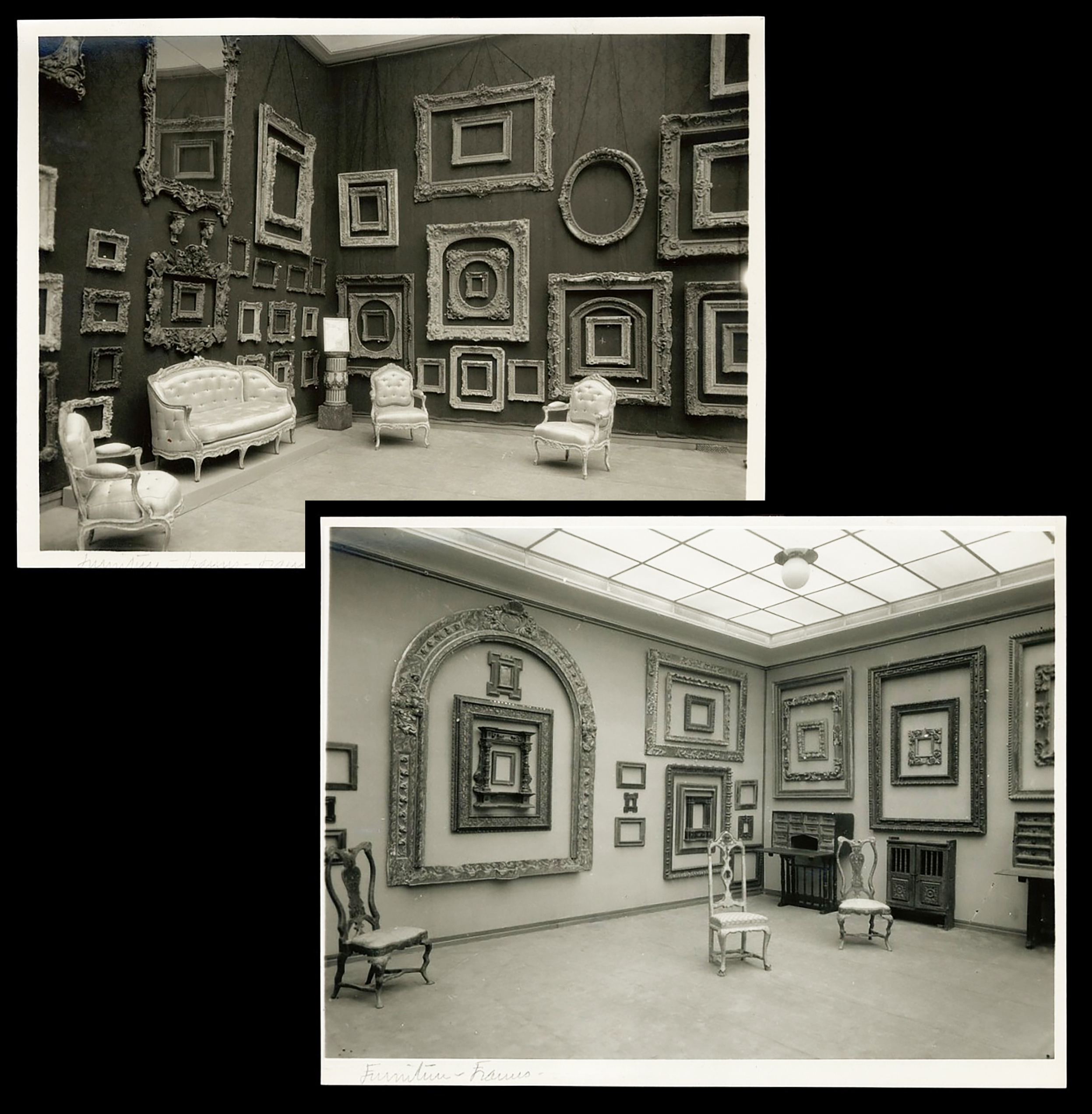

Serge Roche, L’exposition internationale du cadre du XVe au XXe siècle, 1931, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris

Serge Roche’s 1931 L’exposition internationale du cadre du XVe au XXe siècle and the folio of high-definition black-&-white photographs, Cadres français et étrangers du XVe au XVIIIe siècle: Allemagne, Angleterre, Espagne, France, Italie, Pays-Bas, which accompanied it, was a singular and extremely important event. It was at odds with practically everything else in the art world – style, technique and the ditching of anything but a severely minimal frame from contemporary and future paintings. It gave an historical overview of style within period and nationality, and recorded various examples of each style clearly and illuminatingly. It is not so much a highlight in the course of picture frame history as a tall and brilliant lighthouse, irradiating the master sculptures which had been ignored even in the museums which owned them, and pointing out the way for future study.

It took almost half a century, however, before the exhibition and book, Italienische Bilderrahmen des 14-18 Jahrhunderts, by Leo Cremer and Peter Eikemeier, appeared at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich in 1976. It was followed in 1982 by a small exhibition with a folding pamphlet, Framing art: Frames in the collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum, and in 1984 by the results of a mammoth work of research by Pieter van Thiel and C.J. de Bruyn Kops of the Rijksmuseum.

Prijst de lijst, 1984, Rijksmuseum

This was the major exhibition and book, Prijst de lijst, which tackled Dutch 17th century frames; the book was translated into English in 1995 as Framing in the Golden Age by Andrew McCormick, under the sponsorship of John Davies Framing Ltd. It has made a very significant contribution to the study of frames.

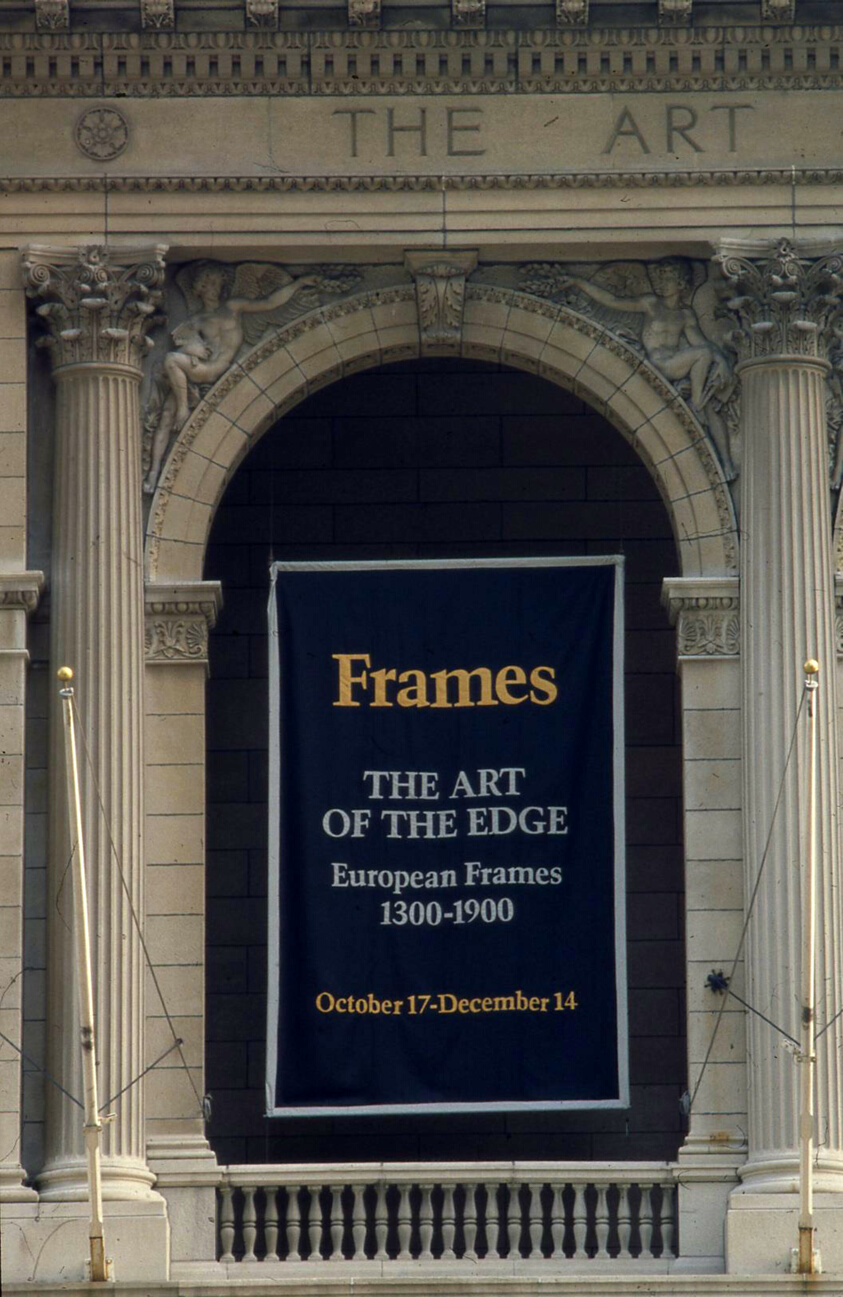

The art of the edge, 1986, Art Institute of Chicago

Two years later came the Art Institute of Chicago’s Art of the Edge: European frames 1300-1900, 1986, with seventy-three frames drawn exclusively from the museum’s own collection; the catalogue also included a very useful 34-page history, as well as a glossary and bibliography.

Of gilding, 1989, Arnold Wiggins & Sons: British carved & water-gilded picture frames, second half 18th century

In 1989 Pippa Mason and Michael Gregory produced the exhibition and booklet, Of gilding…, with a display of frames, objects relating to gilding and books in the gallery of Arnold Wiggins & Sons Ltd, London.

Le cadre et le bois doré, 1991, Galerie Georges Bac, Château de Bagatelle

The Galerie Georges Bac, frame dealers who had been established in Paris for three generations (now in Saint-Ouen-sur Seine), held an exhibition in 1991, Le cadre et le bois doré, in the Château de Bagatelle. The catalogue (ed. Dolly Bac Gross), with essays by Jean-Jacques Gautier and Isabelle Cahn, is now only obtainable through libraries but remains as a paean to French carving and gilding of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The art of the picture frame, National Portrait Gallery, and Frameworks, Paul Mitchell Ltd, 1996-97

Two more British exhibitions took place in 1996-97, Jacob Simon’s The art of the picture frame at the National Portrait Gallery, and Frameworks at Paul Mitchell Ltd, both with accompanying books, which made a total of nine exhibitions for the whole of the 20th century

The 2000s

The clothing of pictures…, 2005, The State Russian Museum

The clothing of pictures…, 2005, The State Russian Museum

2005 saw the first exhibition of picture frames in Russia, at the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg: Oksana Lysenko’s innovative and imaginative vision, The clothing of pictures: Russian frames from the 18th to the 20th century. It was extensive, uniting framed paintings and empty frames, and took five years to organize – not only because many pieces needed restoration, but also because

‘there were no books or articles on the history of Russian picture frames’.

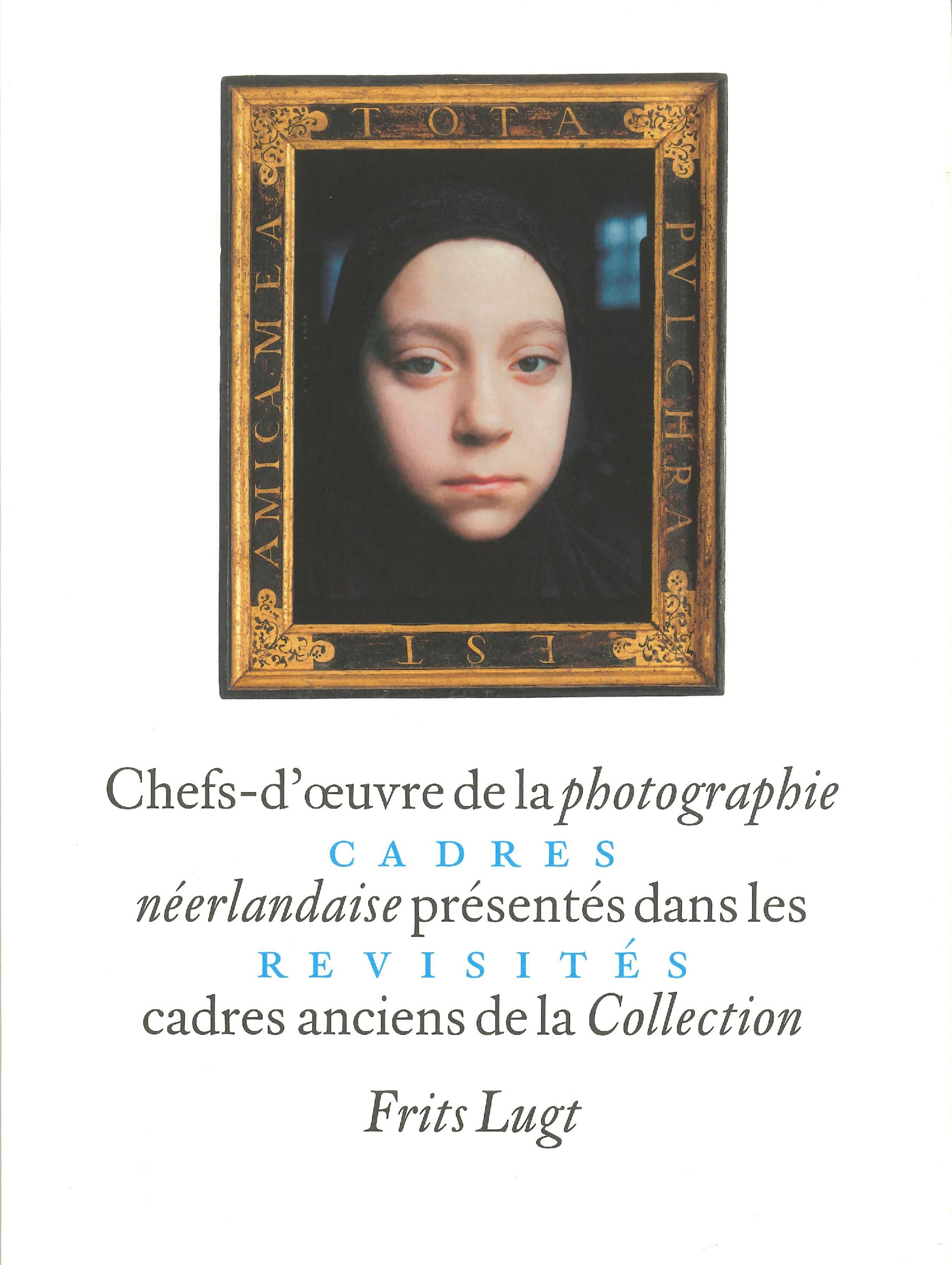

Cadres revisités, 2005, Fondation Custodia, Paris. With thanks to Paul Russell for information on this exhibition

In the same year, 2005, the Fondation Custodia in Paris and the Institut Néerlandais collaborated with the gallery owner Willem van Zoetendaal, who chose portraits by contemporary Dutch photographers and framed them from the Frits Lugt Collection of more than a thousand antique frames. As the review in Photography-now remarks,

‘The exhibition gives the public a new insight into old frames and contemporary portrait photography, thus creating a fascinating dialogue between the present and the past’.

Frames: State of the art, 2008-09, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. Photo: Luke Strosnider

In 2008-09 Henrik Bjerre, Head Conservator of the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, almost singlehandedly produced the large and all-encompassing exhibition, Frames: State of the art, and oversaw the accompanying book of the same name, both of which covered historic European picture frames in the Royal Danish collections, 17th and 18th century frames in Rosenborg Castle, the 19th century court gilder, Peder Damborg, and 19th century Danish artists’ frames.

The 2010s

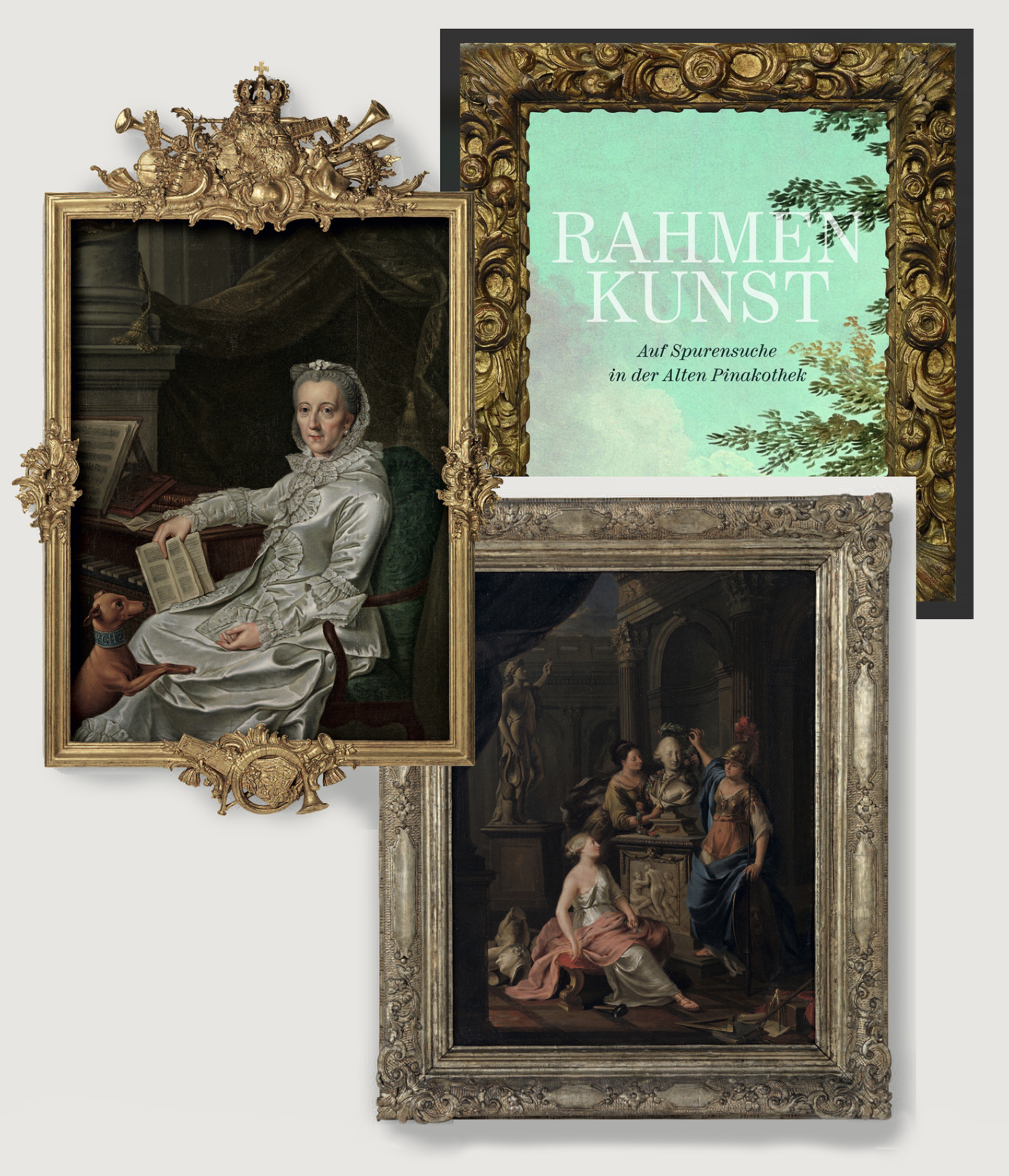

Frame art, 2010, Munich Alte Pinakothek, with a c.1750 Rococo trophy frame after François Cuvilliés on J.G. Ziesenis, Princess Philippine Charlotte of Prussia, Ansbach Residenz; and a silvered panel frame by or after Joseph Effner on J.J. Dornerd, Minerva crowning the Elector, Schloss Schleißheim. With thanks to Angela Meincke for information on this exhibition

The decade opened rather splendidly in the Munich Alte Pinakothek, with an exhibition of ninety-two frames from the Bavarian State Paintings Collection (which holds, altogether, nearly thirty thousand!). These ranged from the 16th to the 19th century, and included works by master carvers/ sculptors such as Paul Egell and Johann von der Auwera, and architects such as the Hungarian Melchior Hefele, as well as frames by and attributed to major names like François Cuvilliés and Josef Effner – many of them made for paintings in the great palaces and residences of Germany. A workshop demonstrating the techniques of framemaking formed part of the exhibition.

Encounter and confrontation…, 2013-14, Museum Ratingen, Düsseldorf

In 2013-14, the Museum of Ratingen in Germany ran a similar exhibition to that of the Fondation Custodia in 2005: Encounter and confrontation: contemporary photographs in antique frames , another slightly peripheral but visually striking display in which fifty-nine photos by important artists were set in antique frames from the family collection of Friedrich Conzen.

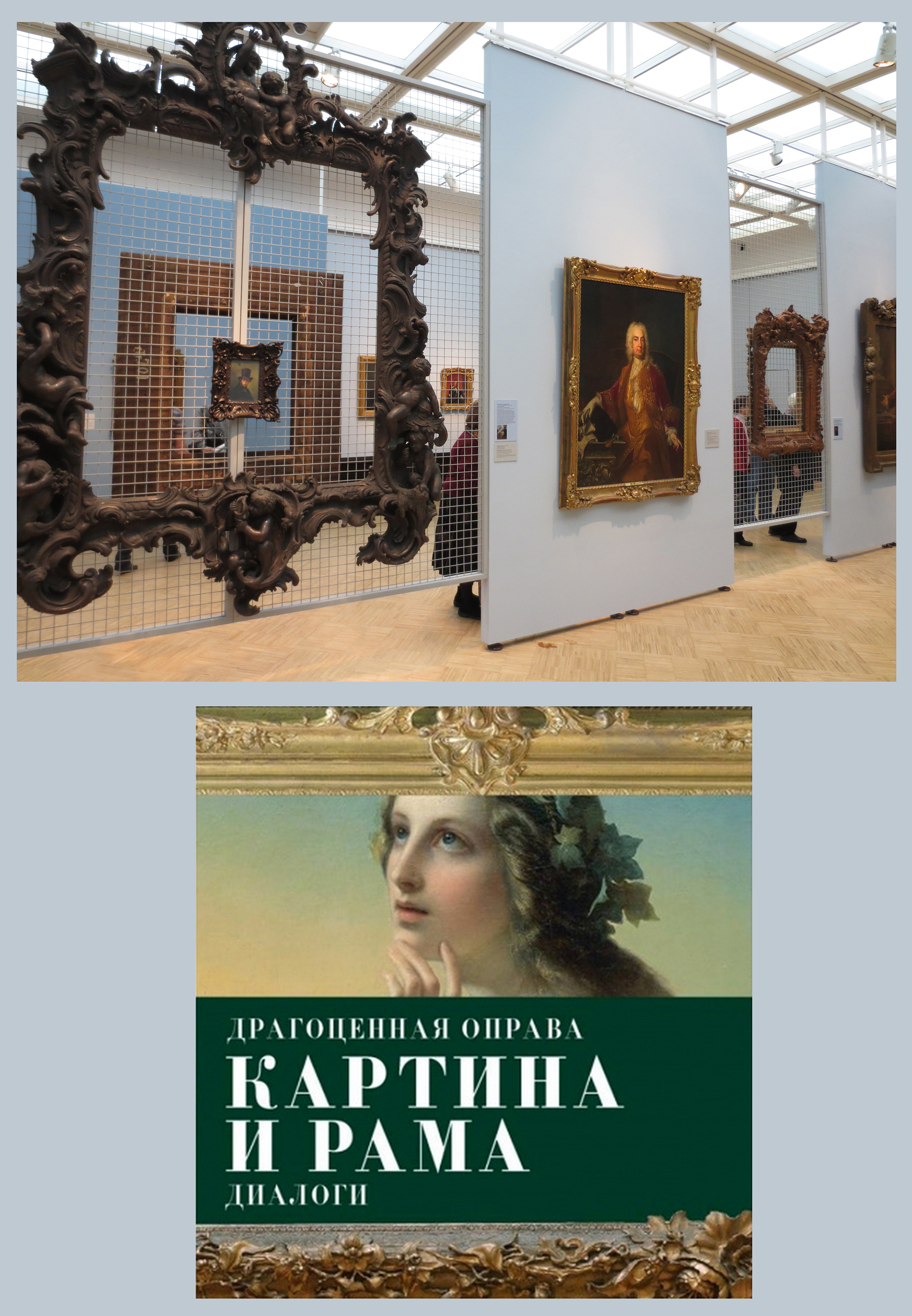

Precious framing. The painting and its frame: dialogues, 2014, State Tretyakov Gallery

Also in 2014, the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow mounted an exhibition which examined the relationship of the frame to the painting it contained – Precious framing. The painting and its frame: dialogues – which included works from the mid-18th to the 20th century. As the curator, Dr Tatiana Karpova noted,

‘…picture and frame in some cases are one integrated work of art. And if the paintings are reproduced without their frames, some of the information, some important shades of meaning are lost.’

The Sansovino frame, 2015, National Gallery

2015 was a particularly eventful year. Peter Schade organized The Sansovino frame at the National Gallery, from April to September 2015; probably the first exhibition to be dedicated to a single style of frame, and one which assembled an extraordinarily varied group of what can only be described as important Mannerist sculptures.

On art and its margins: the frame in the centre, 2015, Dordrechts Museum, with trophy frame made for the Dordrecht Vintners’ Guild in 1682, Huis Van Gijn, Dordrecht

Then the Dordrechts Museum arranged a slightly larger and very varied display, On art and its margins: the frame in the centre (May 2015-January 2016), which covered the framing of paintings from the mid-17th to the 20th century. Interestingly, the hang included reframings along with the previous, rejected frames, giving a graphic demonstration of the effect of different designs on the art they contained.

Louis style: French frames 1610-1792, 2015-16, J. Paul Getty Museum, with view of the entrance and of the interior. Photos: with thanks to Rob Markoff and Steve Shriver

The third exhibition of 2015 was held at the Getty in Los Angeles, and ran from September to the following January. Louis style: French frames 1610-1792 kept the focus of the display within a relatively narrow compass, rather like the National Gallery Sansovino exhibition, but within these limits covered two centuries – from the reigns of Louis XIII to XVI – during which the art of framemaking blossomed, from foliate garlands and borders to the asymmetric extravaganzas of the Rococo, and the cool linear ornament of NeoClassicism. You can download here the Louis Style French Frames Getty exh pamphlet.

Histoires de cadres, 2018, with Charles Angrand (1854-1926), Interior of the Musée de Rouen, 1880, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen. Photos: Louise Delbarre

2018 saw the Histoires de cadres: frames in the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, which – according to the curator, Diederik Bakhuys –

‘originated in the fact that they keep beautiful frames in store, and that the Museum is one of the few in France to have a frame restoration studio’.

It combined a display of empty frames with a ‘frame trail’ through the rest of the museum.

Regards sur les cadres, 2018, Musée du Louvre. Photos: Louise Delbarre

Charlotte Chastel-Rousseau’s large and extensive exhibition, Regards sur les cadres, also took place in 2018, in the Musée du Louvre. It was assembled from the Museum’s collection of about 3,000 empty and 6,000 tenanted frames, focusing mainly on 17th and 18th century examples from Italy, the Low Countries, Spain and Britain, but particularly from France.

KWAB – Dutch Design in the age of Rembrandt, 2018, Rijksmuseum

The third important exhibition of 2018 was KWAB – Dutch Design in the age of Rembrandt – staged by the Rijksmuseum, and featuring many other Auricular objects. By the nature of the style, however, it included a number of important frames, from both the Netherlands and Britain.

Never apart: Frames and paintings by the artists of Die Brücke, 2019-20, Brücke Museum, Berlin

In 2019-20 Werner Murrer brought Never apart: Frames and paintings by the artists of Die Brücke to the Brücke Museum in Berlin; it then moved to the Buchheim Museum. This was an exhibition which focused on the Gesamtkunstwerk – the painting plus frame as one inseparable piece of art.

The 2020s

Breaths were taken during and after the pandemic, although auction sales of empty frames, or of paintings with interesting frames, soon picked up again; these had, of course, continued through the last two-and-a-half decades, along with solo exhibitions by those artists who have their own particular takes on framing.

Another collection: the frames of the Museo Nacional del Prado, 2023, Museo del Prado

In November 2023, however, the focused picture frame exhibition began again; first at the Prado, where the restorer and curator of the frame collection, Gemma García Torres, created a ‘frame trail’ of twenty-nine examples through the various galleries of the museum; also using these in a continuing online exhibition: Otra colección: los marcos del Museo Nacional del Prado or Another collection: the frames of the Museo Nacional del Prado.

Exceptional picture frames, 2024-25, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Finally, from October 2024 to late January 2025, the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza mounted an exhibition based on eleven outstanding frames from the collection – not necessarily original to the paintings, but of particular note. They reflect the interest of the eponymous collector, Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza. As the introduction to the exhibition notes,

‘As an essential part of a painting’s presentation, a frame is more than just a decorative accessory. It helps us to focus and fix our attention on the picture while also separating the real space of the museum walls from the imaginary realm depicted by the painter. Faithful companions to the artworks they protect and embellish, frames have been fashioned in many different styles, depending on the period in which they were made and the interior decorating tendencies of that time, but they have always added value to the painting itself’.

***********************

Parts 2 and 3 of this series describe the 2025 exhibitions in the frame gallery of Olaf Lemke, Berlin (Framing emptiness: an exhibition of inscribed Renaissance frames), and in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Framed! European picture frames from the Johnson Collection).

***********************