Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity: a review of the exhibition, with a general note on his frames

by The Frame Blog

The Fries Museum, Leeuwarden, in the Netherlands, has been holding a major exhibition on the work of one of its native artists – the 19th century ‘Olympian’, Lawrence Alma-Tadema. It is reviewed here by Dorien Tamis, art historian and journalist.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), Entrance to a Roman theatre, 1866, Fries Museum, Leeuwarden

A celebrated artist during his lifetime, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema brought everyday scenes from ancient history to life in his paintings. Now, in an extensive exhibition, more than eighty of these works, along with personal items and film excerpts, have been assembled to tell the story of his rise to fame and explore the ways in which he has defined our image of classical antiquity. The exhibition has been on view in the Museum of Friesland in Leeuwarden, and will open on 24th February in the Belvedere, Vienna (until 8th June 2017), after which it will travel to Leighton House, London (7 July – 29 October 2017).

Alma-Tadema, Self-portrait aged 16, 1852, 58.5 x 48.5 cm., Fries Museum, Leeuwarden

Lourens Tadema was born in the Friesian village of Dronryp in 1836, and trained as a painter at the Royal Academy in Antwerp under Henri Leys. In 1870 he settled in England, eventually anglicizing his name to Lawrence, and hyphenating his middle name, Alma, with his surname to become Lawrence Alma-Tadema. He became celebrated for his depictions of the antique world, either of historical events or of generic scenes enacted against a Mediterranean backdrop or set in sumptuous marbled interiors. He was nicknamed the ‘marbellous’ painter for his ability to depict materials (especially marble, of course) with uncanny realism of texture and tactility. He also engaged in extensive research for every work, to have it appear as true to life as possible – en passant amassing an impressive reference-collection of books, prints, photographs, archeological artefacts and replicas.[1] After moving to Grove End Road, London, in 1883, Alma-Tadema painted less and less, becoming engrossed in decorating his new house instead. He was knighted in 1899, and died in 1912, three years after the death of his second wife, during a trip to a health spa in Germany.

Alma-Tadema, An antique custom, 1876, panel, 28 x 8 cm., Kunsthalle, Hamburg

Although he became both famous and (financially) very successful during his lifetime, after his death Alma-Tadema fell into disrepute, his paintings deemed examples of Victorian bad taste: academic, descriptive and lifeless. His work has undergone a certain re-evaluation since the 1960s, but even so the old perception still lingers. In fact, as long as I can remember it has been almost an art-historical ‘fashion’ to deride Alma-Tadema’s lack of ‘painterly’ attainments. His compositions are considered to be seductive pictures, certainly, but in the sense of pleasurable postcards of an exotic, vanished world, peopled by gauzily clad women, rather than valued as art, the brushwork of a true master. Although not explicitly stated, this exhibition of course invites the viewer to reconsider the verdict. Did I? Well, yes and no. One of the most arresting works, in the painterly sense, is the very last one shown, the unfinished Exhausted maenads after the dance (Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum) [2]. Alma-Tadema conceived the composition as three female nudes, collapsed after dancing and drinking themselves into exhaustion, and depicted it in bold strokes, revealing himself as a sprezzatura painter well worth looking at for those who value this technique. From this painting it is obvious that it is only at a later stage that the painter meticulously finishes every detail and surface of the picture to such an extent that it tends to become stiff and overworked. Whether you share this assessment or not, remains, of course, a matter of taste.

Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), The roses of Heliogabalus, 1888, o/c, 52 ¼ x 84 3/8 in (132.7 x 214.4 cm), The Pérez Simón Collection

The viewpoint offered in the exhibition is another one entirely, that of Alma-Tadema, not so much as painter, but as director. For over a century his paintings have been used as a source of inspiration – even of blueprints – by film directors, for historical dramas ranging from the 1913 epic Quo Vadis, until the much more recent Gladiator by Ridley Scott (2000). Of course, Alma-Tadema himself was involved in theatre too, as a set and costume-designer.

Anna Alma-Tadema, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s study at Townshend House, London, 1884, watercolour, 33 x 45 cm., Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Thaw Collection 2007-27-72

The point of departure of the exhibition is also a valid way to understand the painter’s obsession with decorating his house during his later years: Alma-Tadema as the director of his own surroundings, his house as his own personal film set. He turned both home and studio into a Gesamtkunstwerk, a meeting place of the present and the past. To complement the reproductions of archaeological artefacts – for instance, a replica of the so-called Hildesheim Krater – Alma-Tadema designed his own classicizing furniture, embellished with decorative paintwork.

Alma-Tadema, cabinet doors with Politeness & Courtesy (top panels); Vanity (looking-glass) & Pride (lower panels), c.1871-85, 170 x 45 cm., Fries Museum, Leeuwarden

Motifs cross over between his painted work and his interior design: for instance the couple and the woman in red in the foreground of the Entrance to the theatre (top of article) are also to be seen on painted cabinet doors, where they are meant to symbolize Politeness and Courtesy, according to the inventory written by his daughter.[3] It is interesting to compare the settings of the two works: the painting (Entrance to the theatre) has a wide flat frieze which is used for emblems to do with the subject – comic and tragic masks, and a little player with cymbals dancing along the pole at the top – whilst the stiles of the cabinet become an equally flat frieze around the painted panels, and are decorated with graphic ornaments. The negation of depth in the cabinet contrasts with the painting, where the scene itself has a deep spatial recession, emphasized by the burnished gilt hollow and the inward-slanting sight edge added to the flat frieze of the frame.

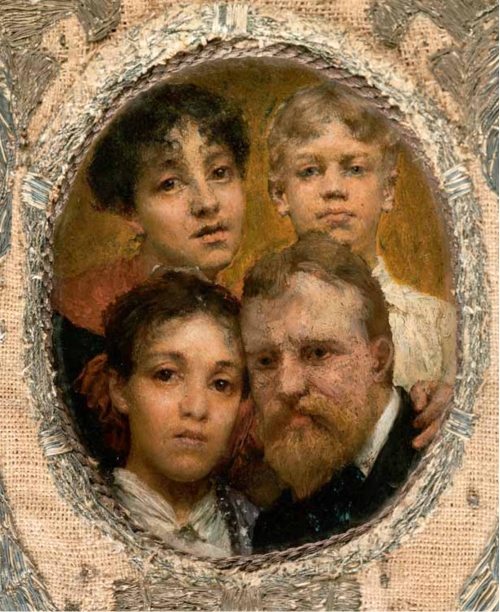

Alma-Tadema, looking-glass with painted medallion portraits of the artist, his daughters & nephew, 1885, miniature on copper 9.8 x 7.7 cm., frame 53 x 41.5 cm., Fries Museum, Leeuwarden

Amongst the pieces of furniture shown in the exhibition, a particularly charming item is a small curved and faceted looking-glass adorned with a miniature portrait of the painter’s family inserted into an oval frame. The frame, thought to have been executed in 1885, has been upholstered with textiles embroidered and beaded in subdued (possibly faded) colours.

Alma-Tadema, looking-glass with painted medallion, detail

The miniature depicts Alma-Tadema himself, his daughters Laurence and Anna by his first wife, Pauline, and his nephew Pieter Rodeck. As his second wife Laura is missing from the little tableau, it is evident that the mirror was a gift to her, in which she could view herself surrounded by her family [4].

Judgement of Paris frame by Filippo Parodi (1630-1702), now containing Ferdinand Vouet, Portrait of Maria Mancini, Palazzo Spinola, Genoa

This is a familiar and conventional trope; the same trick is used (with very different effect) in Filippo Parodi’s Judgement of Paris frame. This now contains a portrait, but it was almost certainly designed to hold a looking-glass. It is carved with the figures of Hera and Pallas Athene on the left and right, and Hermes at the top; he offers the golden apple of Discord to Paris, who points down into the frame, indicating that he should give it to the most beautiful woman in the world – that is, Aphrodite, who is represented by whichever woman looks into the glass.

Alma-Tadema & Laura Epps, The Epps family screen, 1870-71, 6 hinged panels, each 182.9 x 78.7 cm., © V & A Museum /Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Laura was an artist in her own right, who had taken lessons from Alma-Tadema; his teaching method consisted of collaborating with his pupil in portraying members of her family. One result of what turned out to be their courtship was a large folding screen, measuring some 5 metres across, which was set aside and never finished after their marriage. It has an extraordinarily bold, asymmetric L-shaped frame of wide red panels, which indicates a Japanese influence (amongst the objects from Alma-Tadema’s collection now in the Fries Museum is a Japanese bamboo stool), and see William Michael Rossetti on ‘the Dutchman’s taste for Japanese art’ [5].

Self-portraits of Alma Tadema & Laura Epps, oil on panel, 1871, 27.5 x 37.5 cm., in frame 43 x 53.5 cm (closed), & 43 x 78 cm (open), Fries Museum, Leeuwarden

To commemorate their wedding Lawrence and Laura each painted a self-portrait, united by a replica of a Roman frame and hidden behind walnut shutters painted with emblems. This is one of the few exhibits to be graced with a description of its frame in the catalogue:

‘…the two [self-portraits] are united in a frame of a type used in classical antiquity, and often represented in Lawrence’s paintings… The portraits are encircled by an inscription in elongated capitals reminiscent of Pompeiian examples (compare the lettering in Fig. 7, for example), and enclosed by doors painted with emblems – a Dutch tulip on Lawrence’s side, an English rose on Laura’s.’ [6]

Alma-Tadema, Self-portrait in shuttered frame, detail

Alma Tadema, A family group, 1896, panel 30.5 x 27.9 cm., purchased from Miss Anna Alma-Tadema, 1944.© Royal Academy of Arts, London Photo: John Hammond

An imaginary, pedimented version of this work provides the focus for a painting of Laura, her sisters and brother, with her husband in the background, executed 25 years later in 1896. Here, the emblems representing husband and wife have been moved to the same door of the frame, possibly indicating their closeness. See also Fig. 60 in the catalogue – Antistius Labeon: AD 75 (1874, private collection) – a variation of A family group, but in a classical setting, with Roman costumes and frames.

Alma-Tadema, A hearty welcome, OP CXC , o/c 30x 90cm., © Ashmolean Museum. Photo: The Frame Blog

Alma-Tadema often favoured an oblong horizontal format in his paintings (above, in the artist’s characteristic moulding with a deeply canted back edge, decorated with a band of black-&-gold chevron ornament). This is immediately recognizable as the proscenium arch of the theatre (and looks forward to the silver screen); he also frequently uses a compositional view in a wide-angled perspective. Pleading, A question, Amo te, ama me: several versions of a conversation between a Roman youth and a young woman, lounging on a huge marble garden bench, are among his most reproduced paintings to use this effect.

Alma-Tadema, The Pyrrhic dance, 1869, 81.3 x 40 cm, Guildhall Art Gallery (replacement gallery frame)

In The Pyrrhic Dance, one of Alma-Tadema’s first works to be accepted for the Royal Academy summer exhibition, he compresses space in such a drastic fashion that the dancing warriors seem to be constricted within the picture frame, imbuing the painting with a curious atmosphere of suspense.

Alma-Tadema, Silver Favourites, c.1903, panel, 69.1 x 42.2 cm, frame 110 x 71 cm overall. Manchester City Art Gallery . Image courtesy of Manchester Art Gallery

The stage-effect of the paintings, whether in landscape or upright format, is nearly always reinforced in this way by the frames. Alma-Tadema designed the majority of these himself. The aedicular patterns mimic the classical architecture of a temple façade or aedicule, crowned by a flat entablature or a triangular pediment; some of them are in tabernacle form (i.e. in an upright format with an apron and brackets beneath, as above, designed to be hung on a wall, rather than standing on an altar-like support). Many of these frames (unlike the classical altarpieces of the Renaissance) use expanses of undecorated, plain gilding, by means of which the artist – to my mind – creates an even more distinctive partition between the viewer and the picture. The gilding of most frames seems to be in good condition, well preserved or restored. Only in a few some abrasions show the reddish ground underneath the gilding. Although obviously not intended, the effect is not disagreeable, it adds some patina to the whole.

That – apart from a very few crumbs, such as for the self-portrait triptych, above – no information on the original frames is incorporated in the book that accompanies the exhibition (not a catalogue in the strict sense), is unfortunate. This is especially true as the rôle of the frame in his overall composition reinforces the viewpoint of Alma-Tadema as a ‘director’.

Nicolaas van der Waay, Hall of panels at Grove End Road, c.1890-91, pen-&-ink drawing, Fries Museum

In both his London homes, first in Townshend House and later at 17 Grove End Road, Alma-Tadema encouraged his family and his artist friends who visited to donate a painting in a narrow upright format to be included in the wall panelling. Eventually amounting to 45 paintings, the decoration can be read as an album amicorum of the painter and his family. The subject matter ranges from painted interiors – amongst them a depiction of Alma-Tadema’s studio by his sister-in-law, Emily Epps – to marines and landscapes. A moor scene was donated by Sientje Mesdag, the wife of the famous marine painter Hendrik Willem Mesdag; there were also city views, nudes, and even the figure of a Javanese dancer by John Singer Sargent.

Photo of the Hall of Panels, 1902, detail; from The Strand Magazine, December 1902 [7]

The integral framework of the panels consisted of a flat frieze, similar to the frame of the Entrance to the theatre, and to the cabinet doors illustrated above, with a gilt bead and cavetto close-framing the actual paintings. Eventually the panelling was dismantled, and the paintings dispersed. Some of them are still framed in a way closely resembling their original setting (maybe even partly retained from the original panelling); others – including the beautiful nude, The bath of Psyche by Lord Leighton – were reframed in broad mouldings made of unadorned dark wood, better suited to the heavy furniture popular in the 1970s.[8] It is a telltale sign that the only open floorspace is to be found in front of these paintings, in an exhibition that is otherwise very crowded.

The exhibition in Leeuwarden was extremely busy: so much so, that the Museum had problems handling the influx, with queues for admittance stretching through the Museum, lasting for an hour or more. After Leeuwarden, the exhibition travels to the Belvedere, Vienna, and after that to London, to Leighton House; so booking for it in both locations is advisable. Leighton House was the home and studio of Alma-Tadema’s close friend and fellow artist, Frederic, Lord Leighton, who decorated his house in a similar spirit. Both of Alma-Tadema’s London houses embodied the impression the Friesian artist wanted to create, of an interior based on aesthetic principles and archaeological research. Alma-Tadema was first and foremost the ‘director’ of his own setting.

*****************************************************************

As a freelance art historian and journalist, Dorien Tamis writes about nearly anything that catches her interest: from 16th-century warfare to artful embroidery, from justifiably forgotten painters to historical movies. She specializes in the workshop practices of 16th and 17th century Netherlandish painters, and was awarded her doctorate last year for her thesis, ‘Van twee handen geschildert’: werkverdeling tussen schilders in de Nederlanden in de zestiende en zeventiende eeuw (‘Painted by two hands’: division of labour among painters in the Netherlands in the 16th and 17th century).

*****************************************************************

An appendix: Alma-Tadema’s frames

by The Frame Blog

Alma-Tadema, Self-portrait, c.1897, Vasari Corridor, Uffizi

This self-portrait by Alma-Tadema was painted forty-five years after the one near the beginning of the review, above. The sixteen year-old artist and the sixty-one year-old are posed alike, in three-quarter profile, tools in hand, before the pictures they are working on; nicely-jacketed, with white collar and tie, the dispassionate gaze the same, the features clearly recognizable through the decades which separate them – and through the beard and the glasses. But the great difference is that the boy at the start of his career is just working on his picture, because that is all that he sees as important, whereas the mature artist paints himself finishing the portrait in its frame – in this frame, in which it still hangs.

As Dorien Tamis points out in her review of the exhibition, Alma-Tadema was the director of his life, his domestic surroundings, his art, and the way that his art was presented; the frame was an extremely important part of this presentation, and he made sure that, as far as he was able, the style of frame suited the subject. This is the self-portrait requested for the collection which had been begun by Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici in the 17th century, and which hung in the Vasari Corridor, and therefore Alma-Tadema acquired for it a reproduction of a Baroque Florentine leaf frame (it may even have been carved for him in Florence; Spencer Stanhope and Evelyn De Morgan had their frames made there). He then finished the painting in the frame, so you can see in the portrait the edge of the frame which you are actually looking at, around the painting which is also inside the portrait (and which would – if we could see it – contain another frame edge, like a series of reflecting looking-glasses). This artist has grown up to paint infinity, in anticipation of the Surrealists.

Frames with ‘Frankish’ decoration

Alma-Tadema, Queen Fredegunda visits Bishop Praetextatus on his deathbed, 1864, 99 x 138 cm., with frame 133 x 170.5 cm., Fries Museum

Before he got to that point, however, and after the precocious 16 year-old portrait, Alma-Tadema discovered history. His frames are generally thought of in terms of the golden aedicular patterns which (literally) enshrine his larger classical scenes, but his designs are a great deal more varied and interesting than these. He seems to have begun framing his work in a more individual way in the early 1860s; at this point he was painting subjects from the Merovingian past of his country (the 5th-8th centuries AD, when the Franks were ruling a large chunk of northern Europe). He appears to have researched the period carefully [9]; how much he was able to find of furniture in the earliest century is questionable, considering how little there is left of it, but the scene he sets (above) is very convincing. The ornament of the frame is based on Romanesque chevron carvings around stone arches (for instance); it is probably later than the subject Alma-Tadema is painting, but it is also fairly convincingly archaic – mainly because of something which is now lost to us: the vast difference there would have been between this kind of frame decoration, and the normal academic type of frame with which most artists and spectators would have been familiar.

Early frames in ‘classical’ style

Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), Returning home from market, 1865, o/panel, 15 15/16 x 22 ¾ ins, 40.5 x 56.8 cm., The Pérez Simôn Collection

Alma-Tadema, Returning home from market, detail

He became interested in Egyptian history, too, and then – honeymooning in Italy in 1863 – in Rome and Pompeii, where he recorded both the architecture and its carved ornament. One of his earliest ‘Roman’ frames was made for Returning home from market, which has a fairly conventional profile (like Queen Fredegunda) but is decorated appropriately with gilt motifs of buds and small sprigs of bay leaves.

Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), Entrance to a Roman theatre, 1866, Fries Museum, Leeuwarden

Alma-Tadema, Entrance to a Roman theatre, detail

The Entrance to a Roman theatre, which came next, is not only a tour de force of historical reanimation, but signals his intention to integrate the structure of his frames more closely with the contents. The flat façade of this frame, with no subsidiary carved ornamental mouldings – just a burnished cavetto and a deep canted sight edge – would have been extremely innovative and unusual, even by 1866. Millais’s frame for his friend Charles Collins’s painting, Convent thoughts (1850-51), had a very similar frame construction, but the minimalist form which underlay the great moulded lilies fixed to it (also innovative) had had little influence at this point – certainly very little in the Netherlands. The flat frieze which fills most of the body of the frame is close to the ‘studio frame’ used by many 19th century artists to hold the studies and sketches they retained. Alma-Tadema has converted it into the front of a proscenium arch, interpreting the title quite literally, and making the painting of the theatre entrance the prologue, as it were, to a theatrical performance, by adding tragic & comic masks and swags of bay leaves at the top, cleverly suggesting a modern stage curtain – whilst not implying that the Romans also had curtains. The elongated lettering of the title, with its careful serifs, suggests a Latin inscription.

Alma-Tadema, A Pyrrhic dance, 1869, 81.3 x 40 cm, Guildhall Art Gallery, with detail from My studio, 1867, panel, 42.1 x 54cm., Groninger Museum, Groningen

He continued to use conventional frames, presumably partly because he was still experimenting with the ideal formula – the thing every artist wants from his frames – the trademark design; and partly because the destination of some of his paintings might not be as open to innovation as he wanted. As it happened, the Royal Academy in London had already become acquainted with innovating artists, through the Pre-Raphaelites, but Alma-Tadema seems circumspectly to have chosen a NeoClassical pattern for one of his first two exhibits at the RA. A Pyrrhic dance (1869) has now lost its original frame, but in the painting My studio of 1867, what looks like an early version of it is set on the back of the easel, facing the spectator, so that we can see its concave frame with palmette decoration in compo [10].

Diptychs in Roman style

Self-portraits of Alma Tadema & Laura Epps, oil on panel, 1871, 27.5 x 37.5 cm., in frame 43 x 53.5 cm (closed), & 43 x 78 cm (open), Fries Museum, Leeuwarden

Laura Epps, Self-portrait in shuttered frame, detail

However, he had done his research, and began to design frames which were far more individual, and based on ancient architectural and ornamental sources. Some of them would be classically very purist and authentic, as, for instance, the double portrait of himself and his second wife, Laura Epps; he repeated this diptych and its frame for the double portrait of his daughter and son-in-law – Dr Franz Hueffer and Cathy Madox Brown, 1872, OP CIV, private collection.

Trompe l’oeil fresco of a painting, shutters folded back, on trompe l’oeil ‘shelf’, House of the Cryptoporticus, Pompeii. Photo: Davide Peluso

Shuttered paintings of this kind had been found in Pompeii, which he had visited (there is a photo in the exhibition catalogue of Alma-Tadema taking measurements inside one of the houses); the House of the Cryptoporticus has a number of beautifully painted examples.

Alma-Tadema, The picture gallery, 1874, o/c; courtesy of Towneley Hall Art Gallery & Museums, Burnley. THA37360

Alma-Tadema, The picture gallery, detail

He also brought these antique works to life in paintings, including three of a Roman picture gallery, which contains alternative selections of varied frames in the different versions. The example above includes a shuttered frame on the right which is very similar to that made for the double portrait of the artist and his wife, with crossed corners (rather like an Oxford frame [11]). Both the versions of The collector of pictures at the time of Augustus (1866 & 1867) have different but particularly clear examples of framed and shuttered works at the top left, as well as patterns which look as though they could have inspired some of the more Ruritanian artists’ frames of the late 19th century. Michael Squire notes the sources for the works contained in these inventive frames, pointing out that The picture gallery, above, brings together part of an actual Pompeiian floor (the Alexander Mosaic) and elements of frescoed walls as though they were modern canvases, framed as Alma-Tadema himself might have framed them [12].

Moulding frames with ‘Greek’ or ‘Roman’ decoration

Alma-Tadema, Woman & flowers, 1868, o/panel, 49.8 x 37.2 cm., detail. Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Alma-Tadema, Etruscan vase painters, 1871, OP XCIV, o/panel, 42.9 x 28 cm., Manchester CAG. Image courtesy of Manchester Art Gallery

Alma-Tadema, Etruscan vase painters, detail

Alma-Tadema, A bacchante, c.1875, o/ panel, Sudley House, National Museums Liverpool. Photo: courtesy of National Museums Liverpool

Alma-Tadema, A bacchante, detail

As well as these more specialized designs, Alma-Tadema produced a number of very individual moulding frames, which seem to be unique to the particular paintings they contain. These include the design for Woman & flowers, with its double-guilloche top edge, and repeated interlocking garlands of flowers, which is the feminine version of the male bay-leaf garland. Another example is the frame of Etrucan vase painters, in which the pattern of shallow relief interlocking buds on the frieze can be found in Owen Jones’s The grammar of ornament [13], and is noted there as one of the ‘Ornaments from Greek and Etruscan Vases in the British Museum and the Louvre’. Alma-Tadema may well have taken the motif directly from Owen Jones, as the coincidence with the title of the painting is almost too great; The grammar of ornament became the Bible of designers (and framemakers) looking for references for classical patterns of all kinds in the second half of the 19th century. A third classicizing moulding frame holds A bacchante, and has a wide flat frieze decorated with an outline undulating running pattern, based on a simplified version of the ‘Pompeiian No 2’ page in Jones. See, too, the frame of An antique custom (in the review, above), with small images of the implements used in Roman baths – strigils and water scoops – engraved on the frieze.

Alma-Tadema, The roses of Heliogabalus, 1888, The Pérez Simón Collection; detail

Alma-Tadema, Spring, 1894, J. Paul Getty Museum, detail

At the top of the flat border of A bacchante, at the sight edge, Alma-Tadema’s signature stylized scroll can be seen, also in outline; here it holds his hand-inscribed name, but on, for instance, the frame of The roses of Heliogabalus it forms a shallow relief panel on the pedestal, whilst on Spring it is used as an applied title plate on the cornice.

Inscription of a freedman & woman of Sextus Lartidius, Legate in Asia, 5 BC, Wilcox Classical Museum, University of Kansas; purchased 1909

He may have found a stone model for this scroll in his travels, or have come across a reproduction in a book or photo; although not common enough to make it a cliché, inscriptions carved in stylized scrolls, like the one above, show that – as always – Alma-Tadema’s remaking of the classical world in his work had a basis in archaeological research.

Alma-Tadema, A hearty welcome, OP CXC , o/c 30x 90cm.,© Ashmolean Museum. Photo: The Frame Blog

Alma-Tadema, A hearty welcome, OP CXC , o/c 30x 90cm.,© Ashmolean Museum. Photo: The Frame Blog

Alma-Tadema, A hearty welcome, detail

The most frequently-used moulding frame turns up on quite a number of Alma-Tadema’s paintings – for example, on A hearty welcome in the Ashmolean, referred to in the exhibition review, above. This has a geometric canted section in two stages which projects the picture forward from the wall, in a variation on the ogee or convex bolection moulding of a Baroque frame. It looks very much like an adaptation of the canted moulding used by Ford Madox Brown and Rossetti.

D.G. Rossetti (1828-1882), La bocca baciata, 1859, o/panel, 32.1 x 27 cm., detail. Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Rossetti seems to have designed this initially, using it on the small, bust length decorative paintings of women set in a shallow space which he executed in the 1860s; here the moulding was canted on both sides, and decorated with the alternating round indents which explain why Brown called it ‘Rossetti’s thumb-mark pattern’. It functions like an ordinary architrave frame, without pushing the painting forward; instead, it emphasizes the flat, decorative nature of these pictures.

Ford Madox Brown (1821-93), Lear & Cordelia, 1849-54, o/c, 71.1 x 99.1 cm., frame overall 99.5 x 127 x 8 cm., Tate

Brown then adapted the thumb-mark moulding for his own frames by adding another stage of canted moulding underneath Rossetti’s, which does push the canvas out towards the spectator. Sometimes the surface of the lower slope was stepped, and sometimes it was faced with a black reeded moulding, striped with gold leaf.

Alma-Tadema, A favorite custom, 1909, o/panel, 66 x 45.1 cm, Tate

All the variations are notable for their extreme modernity, compared with the rounded, convex, concave and ogee mouldings of contemporary academic or Salon frames; however, Alma-Tadema developed his own in the opposite spirit – he was looking for a frame which stood out through its archaic, pre-modern appearance. Canted mouldings were part of classical architecture, but they were unusual, and it may be that the artist based his design on something like the silhouette of an Egyptian pyramid. He emphasized this aspect with the band of marquetry – black-&-gold triangles of wooden inlay – at the top of the first canted stage, giving the whole frame a hint of barbaric exoticism. He also used the frame unadorned for portraits of his peers and family, and other contemporary works, such as 94° in the shade (1876, Fitzwilliam Museum) and Portrait of Maurice Sons (private collection).

Aedicular & tabernacle frames

His most recognizable settings are, however, the aedicular and tabernacle frames [14] which – like the other Olympians (Lord Leighton, Sir Edward Poynter, Edwin Long, amongst others) – he used as appropriate for larger subject paintings set in ancient Greece or Rome.

Alma-Tadema, Vespasian hearing from one of his generals of the taking of Jerusalem by Titus, 1866, o/panel, 51 x 38 cm., University of Michigan Museum of Art & Archaeology

These designs were in place for the classical subjects he painted from 1865-68, for the twenty-four pictures commissioned by the dealer, Ernest Gambart. Vespasian… (above) was one of these, but there were subjects in landscape form as well as portrait, and their frames also differed.

Alma-Tadema, frame designed & made for Caracalla: AD 211, 1902, Sotheby’s, New York, 8 November 2013, Lot 14

This remained true throughout Alma-Tadema’s life: he used various designs, some with pediments and even acroteria, like the example here, as well as with ornamental modillions or brackets at the bottom. The frame from Caracalla (like the one on the gigantic Roses of Heliogabalus) is a landscape version of the portrait frame on Silver favourites (1903, Manchester CAG).

Alma-Tadema, frame designed & made for The golden hour, 1908, Sotheby’s, New York, 8 November 2013, Lot 15

Some have just a crowning entablature, and a relatively plain structure which is enlivened with runs of ornamental moulding. They are all carefully adjusted to the proportions and balance of the painting, and – being designed by the artist – are part of his whole vision for the complete work of art. Given this, it seems an act of almost unbelievable vandalism and selfishness that the owner from whose estate the two empty frames shown here were posthumously sold, should have removed the paintings and sold them separately at an earlier point, filling the orphaned frames with reproductions of the two works so that he could still ‘enjoy’ them, whilst having profited from their sale.

Alma-Tadema, Love’s missile, OP. CCCXC, 1909, 19 3/4 x 15 in., 50 x 38 cm., Sotheby’s, London, 14 December 2006

Love’s missile, which retains its almost identical frame, demonstrates the loss for the painting of The golden hour in having been separated from its frame and sent naked into the world. It is clear from the former work that Alma-Tadema used the aedicular frame as it had been designed in the Renaissance, when a classical altarpiece frame provided an opening like a door or window through which the spectator could look onto another world. In the Renaissance, the spectator would have been a worshipper, looking onto a celestial scene; in 19th century Britain, he or she was a prosperous citizen of Victoria, looking through a doorway into an imagined but realistic view of a classical world which echoed his or her own in the emotions or situations it conjured, and in the analogous furnishings and decorative schemes that it showed.

Frames in ‘Egyptian’ style

Alma-Tadema, An Egyptian widow, 1872, o/panel, 74.9 x 99.1 cm., Rijksmuseum

Alma-Tadema, An Egyptian widow, detail

For subjects where the time and scene was even more exotic than the classical past, with which most educated Victorians would have been at least slightly familiar, he used frames as he had for his Merovingian paintings – conventional shapes and structures, but decorated with appropriate motifs. He painted several Egyptian subjects: The Egyptian widow is framed in ornaments which may have been inspired by the relevant pages of Owen Jones (plates IV, V & VI), or from exhibits in the British Museum. The scotia is full of repeated naturalistic plants, arranged in sprays set alternately pointing up or down; these may be willow leaves (found in tombs) , or bindweed, associated with funerals, or leaves of the persea (the Tree of Life).

Alma-Tadema, The death of the Pharoah’s firstborn son, 1872, o/c, 77 x 124.5 cm., Rijksmuseum. Photo: Rob Markoff

Alma-Tadema, The death of the Pharoah’s firstborn son, details. Photos: Rob Markoff

The death of the Pharoah’s firstborn son, although painted the same year as The Egyptian widow, has a much more ambitious and avant-garde frame. This may be because, although the dealer Ernest Gambart commissioned it in 1872, and sold it in 1878, Alma-Tadema bought it back himself in 1879, kept it until his death, and left it to the Rijksmuseum; thus the frame may date from some time after the painting. The banded and geometric ornaments at the back and on the top edge, with clasps like stylized feathers or palm leaves, seem again to be based on examples illustrated by Owen Jones; however, the motifs at the sight edge are made up of repeated hieroglyphs, arranged in a running pattern around the frame. They appear to be composed of two opposed versions of the glyph for a cobra, on either side of a cartouche, with the round symbol for the sun or Ra above. As with the group of frames with the triangular moulding, this unique Egyptian-style attributive design has links with the innovative geometric patterns used by Ford Madox Brown and Rossetti – the canted and fluted back edge, bordered by a black moulding striped with gold, is especially reminiscent of Pre-Raphaelite frames.

Alma-Tadema, Cleopatra, 1877, o/panel, 19 x 26.7 cm., Auckland Art Gallery, NZ Museums

The frame for Cleopatra is even more exotic, using as a model the structure of an Egyptian temple, in analogy with the artist’s classical aedicular frames. The immediate impression is of the ornament – the winged scarabs in the centre; and the cobra, sun and cartouches from The death of the Pharoah’s firstborn… at each end of the top frieze; the falcons on the base, and the ankh on the right [15].

The temple of Khnum at Esna, Egypt. Photo: John Compana

However, the form of this frame is particularly striking: it has the same tapered outer contour, inner right-angled aperture, flared entablature and simple mouldings as can be seen in, for example, the temple at Esna, revealing how scrupulous Alma-Tadema’s research was in all respects. But this would not have been as simple a commission to the framemaker as one of the classical aedicules which had become fashionable amongst artists in the 1870s; Leighton, Poynter, Burne-Jones, Strudwick, Spencer Stanhope and Evelyn De Morgan all used versions for their work. There would have been a point at which a core of London carvers and gilders became very familiar with, and expert at producing, frames which were fundmentally laminated planks of wood, decorated with mouldings which could be mechanically shaped, some simple carved ornament, and additional compo decoration. The pylon-shaped frame for Cleopatra was far more outré, and therefore more complicated to make. It appears to be the only surviving example of this pattern; perhaps it was a special commission. The meeting of Anthony & Cleopatra (1883), does not have an Egyptian frame, but a classical aedicular pattern – presumably because the meeting happened at Tarsus in Turkey (part of the Roman Empire), rather than in Egypt: historical accuracy, again. It is interesting to speculate, in this light, on the frame Alma-Tadema designed for The finding of Moses (1904), given that it was commissioned for Sir John Aird, who had bought The roses of Heliogabalus in 1891 [16]; perhaps it is hidden in someone’s attic, somewhere (please check your attics).

The framemakers

We have a couple of names for framemakers patronized by Alma-Tadema, identifiable mainly through labels on the reverse of the paintings; none of these seem to be earlier than 1879 (information would be welcomed as to framemakers from before this date, or from different firms).

Alma-Tadema, A reading from Homer, 1885, o/c, 36 1/8 x 72 1/4 ins, 91.8 x 183.5 cm., courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art, The George W. Elkins Collection. E1924-4-1

Alma-Tadema, A reading from Homer, detail

The most important framemaking business is that of Dolman (Reginald Dolman & Son, of 6 New Compton Street, Soho), which had been set up by a James Criswick in the early 19th century, and, through changes of partnership, transferred to the control of Reginald Dolman in 1877 [17]. Alma-Tadema may have been using Dolman as his framemaker well before 1879, since in 1880 he recommended him to the National Gallery in replacement of Henry Critchfield, and a year’s knowledge seems sparse for this prestigious connection. Having found a capable firm he appears to have continued to use it for the next thirty years or more (a letter in Manchester City Art Gallery archives indicates that the artist wanted his client, a Mr Markham, to use Dolman to frame a latish painting of the Coliseum [18]). A reading from Homer and a portrait of Alfred Waterhouse (1891, National Portrait Gallery, London) both have Dolman’s labels, and are closely related in their use of wide plain friezes bordered by egg-&-dart and acanthus leaf tip decoration, and their play of canted and concave mouldings.

There seems to be no evidence of Alma-Tadema employing Foord & Dickinson, the major resort of artists such as Rossetti and Holman Hunt, and others whose classical aedicular frames were quite as striking as Alma-Tadema’s, such as Burne-Jones and Leighton. He does seem to have used the firm of Thomas Agnew, which started out in Manchester at the beginning of the 19th century, adding a branch in London in 1860, but continuing to produce picture frames in its northern base [19]. The Etruscan vase painters (1871, Manchester CAG) has an Agnew’s label on the reverse, as does one of Laura Epps’s drawings; we know that Alma-Tadema painted work specifically for Agnew’s to sell in their rôle as picture dealers, so it is logical to assume that they would also have framed those paintings themselves (presumably in accordance with Alma-Tadema’s designs).

The question of Thomas Maw as a framemaker is puzzling. Vern Swanson, in his catalogue raisonné of Alma Tadema’s work, notes that his frames were made by ‘Thomas Maws’ [20]. Information from the Fries Museum has enabled Jacob Simon to extend the article on Maw on the NPG’s Directory of British Picture Framemakers [21], but he has been unable to discover any evidence that Maw actually did make any of Alma-Tadema’s frames. He was born in 1851, and recorded in the various censuses as a carpenter & joiner, or just as a joiner; Alma-Tadema left a bequest to ‘my carpenter Tom Maw’. It is clear that the complex decorative schemes implemented by the artist and his wife in both their homes – in Townshend House from 1871, and in 17 Grove End Road from 1885 – would have needed a great deal of joinery, what with the niches, panelling, cupboards, stairs, window seats, shelves, cabinets made of antique panels, etc. [22]; and the Hall of Panels, for example (in both houses), with its inset paintings in small mouldings, would have been the kind of thing that a jobbing carpenter would naturally be asked to construct.

Alma-Tadema, frame designed & made for Caracalla: AD 211, 1902, Sotheby’s, New York, 8 November 2013, Lot 14

Alma-Tadema, frame designed & made for The golden hour, 1908, Sotheby’s, New York, 8 November 2013, Lot 15

However, although the catalogue entries on Sotheby’s website for the two empty aedicular frames which previous held Caracalla and The golden hour state that these were ‘designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and made by Thomas Maw’, it does appear (pace Vern Swanson) that these have been made by someone with access to reverse boxwood moulds (and/or the means of carving them), an ability to make and manipulate compo expertly, to carve well and engrave into gesso; also the skills of a good gilder. It is difficult to believe that an artist as productive as Alma-Tadema, who was used to dealing with the likes of Sir John Aird and Henry Marquand, and to exhibiting his work in the Royal Academy and in the Parisian Expositions Universelles, Belgian International Expositions and American Worlds Fairs, would use his domestic carpenter for realizing his many frame designs professionally. This is underlined by his recommendation of Dolman to the National Gallery, and by Dolman’s gaining the work because his was the more economical application; and further, by the fact that Alma-Tadema would also have needed an expert art handling and packing service, which most commercial carvers & gilders had been offering for many decades. For an interesting sidelight on the complexities of reproducing one of Alma-Tadema’s frames today, see this article on artdaily.org. It gives some sense of the processes involved, which would probably not have been achievable by a simple carpenter – at least, not as frequently as would have been required by a prolific professional artist.

The exhibition

Alma-Tadema’s work has been due a major exhibition for a long time; this one is in most areas all-encompassing, covering his furniture designs and his own interior decoration, as well as his paintings. It is therefore an even more incomprehensible lack to have missed out a chapter on the great number of varied and imaginative artist’s frame designs which can be seen in the exhibition and elsewhere.

*****************************************************************

[1] Much of Alma-Tadema’s collection is now held at the University of Birmingham; a significant number of objects were acquired by the Museum of Friesland – see Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At home in antiquity, ed. Elizabeth Prettejohn & Peter Trippi, exh.cat., 2016, pp. 48-49

[2] Ibid., pp. 70-72.

[3] Ibid., pp. 31-32

[4] Ibid., p. 28.

[5] Ibid., p. 79

[6] Ibid., p.59

[7] Ibid., fig. 148

[8] Ibid., pp. 90-95.

[9] Ibid., p.19

[10] NeoClassical patterns such as these had become popular from the 1760s, fed by the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Napoleonic Directoire and Empire frames were decorated with anthemia and palmettes, and by the 1820s Friedrich Schinkel had designed a standard frame for the Berlin Gemäldegalerie, with palmette corners & centres . In the 19th century these examples made similar motifs, executed in compo, the appropriate choice for any subject (including landcsapes) connected with the classical world – eg Edward Lear’s View of the Temple of Apollo at Bassae, Fitzwilliam Museum, 1854-55.

[11] 19th century Oxford frames: fortuitously and completely accidentally slightly ‘Roman’ in this respect. See Jacob Simon’s study on the design.

[12] Michael Squire, ‘Introduction: The art of art history in Graeco-Roman antiquity’, Arethusa, 43 (2), 2010, The Johns Hopkins University Press, p.133–35

[13] Owen Jones, The grammar of ornament, 1856, ‘Greek No 2’. plate XVI, no 7.

[14] Aedicular frames are free-standing structures which are made to be supported by an altar, shelf, or even the floor; tabernacles are made to hang on the wall, and have an undercarriage – either a shaped ‘apron’ or (like some of Alma-Tadema’s works) a pedestal or predella panel which slopes back towards the wall and is supported on each side by ornamental brackets or modillions.

[15] In one of its few acknowledgements of the artist’s frames, the exh. cat. does note (of Alma-Tadema’s influence on Klimt) that, ‘ The wide gilded frame on the Portrait of Josef Pembauer (1890) was decorated by Klimt with hand-painted figures and objects based on ancient models. Tadema had similarly decorated the frame of his Cleopatra – exhibited at the Kunstverein in 1875 – with Egyptian figures and hieroglyphs. ‘ Op. cit., p. 160

[16] Exh. cat., op. cit., p.129. The frame was lost in 1955, when The finding of Moses was bought from a London dealer, the painting was apparently discarded outside the gallery, and its frame disappeared with the buyers.

[17] For Dolman’s career and works, see the NPG Directory of British Picture Framemakers, under ‘James Criswick’.

[18] If Henry Marquand had not died in 1902, it might be tempting to see this as the artist’s Friesian approximation of one of his wealthiest clients’ names, and imagine a further commission, to go with Amo te ame me, A reading from Homer, and Alma-Tadema’s grand piano.

[19] For Agnew’s, see the NPG Directory…, op.cit., under ‘Vittore Zanetti… Thomas Agnew‘.

[20] Vern Swanson, The biography and catalogue raisonné of the paintings of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1990, p. 87.

[21] Ibid; under ‘Thomas Maw‘

[22] There are a great many pictures of rooms and furnishings in both houses in the exh. cat., op. cit., in the chapter by Charlotte Gere, ‘The Alma-Tademas’ two homes in London’, pp. 75-97

Impressive, meticulous scholarship! Thank you!

LikeLike

You’re very kind! – thank you for reading it.

LikeLike

Nice note on historical accuracy! Another reason that it has very little of ancient Egypt (other than the woman playing the aulos, the cartouche and the incense horns) is because Egypt was part of the Greek world, with a Greek aristocracy. Cleopatra is very correctly Grecian here.

LikeLike

I’m so glad that you enjoyed it. Alma-Tadema had a very exacting archaeological approach to his paintings and the decoration of his frames, whether they were Greek, Roman, Merovingian or Egyptian, and it’s fascinating to see these accurate setting peopled by models who are usually stigmatized as being Kensington Victorians…

LikeLike

thank you for the wonderful post, I’ve learned a lot!

LikeLike

Thank you for such a nice comment; I’m very glad that you liked this article – and thank you for the 5 stars on FB, as well… 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

GREAT ! THANKS ! @TheFrameblog One of my favorite artists and bar-none the best designer of frames to enhance art.

LikeLike

Well, what a lovely response! I’m glad that you’ve enjoyed the article, and thank you for taking the time to comment.

LikeLike