Burne-Jones’s picture frames

The recent exhibition of work by Edward Burne-Jones at Tate Britain (24 October 2018-24 February 2019) revealed the extraordinary variety and quantity of his creations, and the many different media in which he worked – oil painting, watercolour, stained glass, low-relief gesso, tapestry, painted furniture, metalwork, mosaics – in a career of only 42 years. A salient feature of the exhibition, highlighted by so many paintings and objects brought together into one location, was the number of frame designs he had produced for his work over the years, and the degree to which they complemented and enhanced it. This article on his frame is adapted from one with the same title, first published in The Burlington Magazine in June 2000.

Burne-Jones’s birthplace in 1833: 11 Bennett Hill, Birmingham; engraving used for the frontispiece of Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones

Edward Burne-Jones had good reason to be more than usually sensitive to the effect of framing on his paintings. His father was a carver and gilder, and he had been brought up between the show-room and the workshop of a house whose pilastered façade resembled a renaissance altar-piece[1]. Furthermore, his introduction to contemporary art came through the Pre-Raphaelites, by whom the frame, clothing the naked picture, was considered integral to a work of art. In the early years of his career he experimented with frames which, like his paintings, were strongly influenced by the decorative designs of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown. Thereafter, as he adopted more classicizing influences in his work, he turned to NeoRenaissance models, including the aedicular or temple-like ‘altar-piece’ frame which had been reintroduced in the 1860s by Holman Hunt and Alma-Tadema [2]. His early frames are highly derivative, but the frames of his mature style are not derived from those of his fellow artists but are distinctively his own.

Burne-Jones had intended to maker a career in the church, and read theology at Oxford where he met William Morris. Having set up a student magazine together, they fatefully contacted D. G. Rossetti to invite him to contribute to it, and then, when they met him, were both inspired to abandon the church for art. Morris eventually settled on design rather than fine art, and in 1861 set up the firm of Morris, Marshal, Faulkner & Co. (later Morris & Co.), which included Rosetti, Ford Madox Brown, Burne-Jones, and the architect and designer Philip Webb along with the named partners. It produced decorated furniture, stained-glass, tapestries, murals, jewellery and church furnishings, in several of which branches of design Burne-Jones became involved.

His first attempts at frame design may have been catalyzed by this association with William Morris [3], but they also indicate a particularly close working relationship with Rossetti and Brown, who together created some of the more striking Pre-Raphaelite frames, even corresponding about the details of their designs [4]. In the 1850s Rossetti and Brown had been experimenting together with simplified geometric shapes, influenced by early Netherlandish picture frames.

Ford Madox Brown (1821-93), Lear & Cordelia, 1849-54, o/c, 71.1 x 99.1 cm., frame c.1863, Tate Britain

The main features of their designs were wide flat friezes, broad giltwood inlays with oversized bevels at the sight edge, inset ornamental roundels, and the use of vertical butt joints rather than mitres. From 1861 the inlays or mounts were gilded directly on the wood, rather than over gesso, in what must then have seemed a surprising revelation of the texture and grain of the oak. Rossetti’s ‘thumb-mark’ pattern was also introduced – an outer frame of triangular section with alternating indented semi-circles. A further development was the repetition of the oversized bevel on the back edge of the frame itself.

The introduction of these various elements marks a significant break with the established vocabulary of picture framing in the 19th century. Brown’s and Rossetti’s innovations express what would become common concerns: the artist’s wish that his work be framed in an appropriate setting, either designed or carefully chosen for it; that the frame should be, in Ruskinian terms, faithful to its materials (showing the texture of wood beneath the gilding, and renouncing the masquerade of compo as carved wood); also that the frame should not be restricted to a pale imitation of 18th century types, but by blending earlier patterns with innovatory features should create a fresh, contemporary style. These frames replaced conventional Baroque and NeoClassical architectural ornament with geometric decoration without sacrificing any richness; they anticipated the flat reeded and fluted borders used by Whistler and Degas from the late 1870s; and they reintroduced the idea of painted frames. The more successful marriages of the avant-garde and the antique also produced some of the most beautiful frames of the 19th century.

A number of Burne-Jones’s watercolours have frames identical to those designed by Brown and Rossetti during the 1850s; and interestingly he seems to have retained some of those patterns for occasional use throughout his career. The paired settings of Sidonia and Clara von Bork (Fig. 2), which were painted at Morris’s home, the Red House, are early examples of these Brown/Rossetti designs; they were actually made by Burne-Jones’s father. In October 1860 his son wrote to him,

‘How soon can I have those frames? I am waiting for two of them now to sell the drawings they belong to – it makes such a difference having them in frames, that I don’t care to shew them without.’ [5]

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Sidonia von Bork, 1560, 1860, watercolour & gouache on paper, 33.3 x 17.1 cm., Tate Britain

The pictures have kept their gilt oak, butt-jointed mounts with the titles on dark gold scrolls at the bottom, and Sidonia, above, still has the original outer frame of slender astragals set close together and decorated with bay leaves. This frame re-appears on several later studies, and is clearly in direct imitation of Rossetti’s frames [6].

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Clara von Bork, 1560, 1860, watercolour & gouache on paper, 34.2 x 17.9 cm., Tate Britain

Unfortunately, however, Burne-Jones’s father was not the most competent of framemakers, and the bay-leaf astragals around the pendant, Clara von Bork, have had to be replaced. As Georgiana Burne-Jones noted,

‘… the father was very happy in framing his son’s pictures, but, alas, any original design which must be exactly carried out baffled the skill of his small workshop, and Edward had gently and by degrees to let the arrangement drop through.’ [7]

His father’s skills were patently not up to the innovations of the 1860s, let alone the canon of designs subsequently amassed by Burne-Jones. In this first decade they are almost exclusively derived from work by – and probably made under the aegis of – Brown and Rossetti.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Merlin & Nimuë, 1861, watercolour & gouache on paper, 64.2 x 52.1 cm., Victoria & Albert Museum

Examples include the frames of Merlin and Nimuë (this has an inscribed architrave frame, a gilt oak mount with butt-joints, and a sight edge of dark stained oak); also Cupid’s forge, which has a similar outer frame but with added roundels and an unelaborated gilt oak mount[8]; those of The backgammon players, adapted from the Pre-Raphaelite ‘reed-&-roundel’ frame[9], and Cinderella with bay leaf mouldings like those on the Von Borks [10].

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Fair Rosamund & Queen Eleanor, 1861, mixed media on paper, 19 ½ x 14 ¾ ins (49.5 x 37.5 cm.), Yale Center for British Art

Then there are the various versions of Queen Eleanor hunting down Fair Rosamund in her bower; of which the one in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art also has a bay leaf outer frame, whilst another version has a frame which was praised by Ruskin’s father [11].

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The merciful knight, 1863, watercolour & body colour on paper, 101.4 x 58.6 cm., Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Other examples include The merciful knight, which has lost its original outer frame but retains its inscribed giltwood mount set with sunflower roundels, and the triptych of The Nativity in Oxford, set in simple flat ‘early Netherlandish’ frames, hinged together and decorated minimally with engraved lines, like Merlin & Nimuë [12].

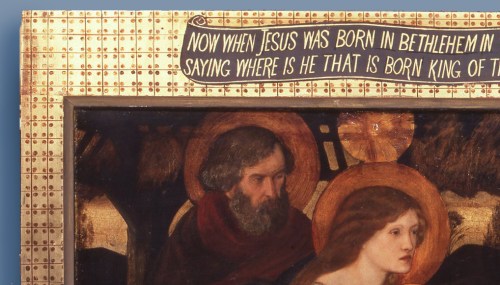

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Adoration of the kings & shepherds triptych, first version: 1860-61, o/c, central panel with The Adoration (108.6 x 156.2 cm.) & left-hand wing with the Angel of the Annunciation (108.6 x 73.7 cm.), in their original frames of c.1862; Tate Britain

The frame of Burne-Jones’s first large work in oils is similarly a compilation of Pre-Raphaelite elements, and its history raises the possibility that Burne-Jones selected the pattern under the direct guidance of Brown, who was working almost simultaneously on a very similar frame of his own. The Adoration of the kings and shepherds, a triptych of separate panels with The Annunciation on the wings, is Burne-Jones’s first version of an altarpiece for a Gothic Revival church in Brighton. It was finished in 1861, but almost certainly not framed then, as Burne-Jones decided to paint a second, simplified version [13].

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Adoration of the kings & shepherds triptych, second version: 1861, o/c, plus centre panel, and detail of that panel (top left-hand corner), private collection

Philip Webb (1831-1915; designer) The backgammon players, cabinet, 1861, pine, leather, brass, copper, 73 x 45 x 21 ins overall (185.4 x 114.3 x 53.3 cm.), painted by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), and detail, Metropolitan Museum, New York

This second triptych, framed and installed in the church on its completion (also in 1861), had each panel set in a flat, smoothly-gilded border painted with a grid of black lines and dots. This is very much in the style of the painted furniture Burne-Jones had produced with Morris in the 1850s, which is Pre-Raphaelite in its very simplified structure, and a cross between re-imagined mediaevalism and embryonic Arts & Crafts in its ornamental details and decorative finish. It is quite as avant-garde in its way as the earliest frames designed for their work by Ford Madox Brown, D.G. Rossetti and Holman Hunt.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Adoration of the kings & shepherds triptych, first version: 1860-61, o/c, right-hand wing with the Virgin Annunciate (108.6 x 73.7 cm.), in its original frame of c.1862/63, and detail of left-hand wing; Tate Britain

The first version of The Adoration… remained with Burne-Jones until 1862, when it was accepted by the executors of T.E. Plint, the Pre-Raphaelite patron, against money received by Burne-Jones from Plint. It was presumably framed at that point, rather than in 1867 when it was bought by G.F. Bodley, the architect and a friend of Burne-Jones. The frames of the three panels of this first version are almost certainly original; they are of the right age, and the varnish, which is bound in a series of glazes to the paintings, also covers the frames [14]. Their structure is remarkably similar to the deeply bevelled reverse frame used by Ford Madox Brown on Lear & Cordelia, (a reverse frame projects the picture forward from the wall surface, which is particularly suitable for a work such as an altarpiece with a long viewpoint). Both Brown’s and Burne-Jones’s frames have four grooves cut longitudinally down each outer bevel, echoed by a smaller grooved bevel at the sight edge. Brown crowns his frame with the gilt ‘thumb-mark’ moulding, while Burne-Jones has a simple convex top edge; both have a series of small roundels or paterae set into the flat friezes [15].

Ford Madox Brown, Lear & Cordelia, 1849-54, detail; & Burne-Jones, The Adoration of the kings & shepherds, 1860-61, detail of left-hand wing; both Tate Britain

Brown’s frame for Lear & Cordelia, was completed in January 1863, having presumably been ordered during the previous autumn from the Pre-Raphaelites’ frame maker at that time, Joseph Green, whom Brown ‘had told … to employ all or any of my patterns’ [16]. If Burne-Jones’s first Adoration altarpiece were indeed framed to give to Plint’s executors in 1862/63, rather than later, when Bodley acquired it in 1867, then he must have sent it to Green at almost the same time as Brown sent his Lear & Cordelia, and with Brown’s blessing. His intimacy with Rossetti and Brown is amply illustrated by this use of their framing patterns, whereas other potential pirates seem to have been warned off [17]; and it is most probable that he adapted the Adoration design under their tutelage, adding his own convex top edge. He remained attached to elements of this design throughout his career, for instance employing flutes or grooves – either gilded or parcel-gilt – on the flat wooden frames used for display in his studio (see below).

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Saints Apollonia & Agatha, copies after Bernardino Luini, 1862, watercolour, 37.5 x 25 cm., and 32.5 x 21 cm., Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro

The most outstanding of Burne-Jones’s early Pre-Raphaelite designs is the extraordinary double frame of his copy after Bernardino Luini’s Saints Apollonia and Agatha, which he painted for Ruskin during their trip to Italy in 1862. The frame is a copy too – an almost exact copy of Rossetti’s 1863 frame for his diptych, The Salutation of Beatrice on Earth and in Eden [18]. It is even labelled on the back to this effect (although not in the artist’s hand):

‘The wise and foolish Virgins

Frame copied from one designed by D.G.Rossetti’ [19]

D.G. Rossetti (1828-82), The Salutation of Beatrice on earth and in Eden, 1859, o/ pine panels, each 74.9 x 80 cm., framed 1863, overall size 101 x 202 cm., and detail, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Ford Madox Brown, Jesus washing Peter’s feet, 1852-56, reframed 1865-66, and detail, Tate

The black reeded frame crossed by bands of gold leaf was one of Rossetti’s most successful designs; it is linear and geometric in his and Brown’s favoured style, its spareness raised to luxury by the contrast of colour. It appears again in the black and gold outer frame of Brown’s Jesus washing Peter’s feet, which was reframed ten years after its completion to take advantage of the innovations their partnership had produced. Rossetti’s 1863 Salutation frame seems to be the first appearance of the black reeded element, and Burne-Jones’s frame must have been either copied directly from the prototype, or made simultaneously by Green. It is even possible that the blossoms painted on the gilt oak mounts of both may have been Burne-Jones’s contribution, since the chequered ground of the squares which holds them is reminiscent both of Morris’s painted furniture and of the patterned frame of the second Adoration triptych (above).

Simple and modern in structure, almost completely devoid of conventional ornament, these frames nevertheless create an outstandingly rich decorative effect, and represent one of the high points of Victorian artist-designed settings. They were seminal for the immense burst of creative frame design which took place during the next forty or so years.

However, they also mark the passing of Burne-Jones’s close co-operation with Brown and Rossetti. From about 1870 most of his larger frames were modelled on Italian Renaissance patterns, the early designs being used for water-colours, sketches and cartoons. At the same time he modified his Ruskinian notion of truth to the materials used, since the ornaments he came to favour could not be reproduced, without huge expense, except in compo; nor did they sit easily on a gilt oak ground. These changes followed the alteration in his own painting style, as his taste broadened to include Michelangelo and other later artists.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Venus, 1861, o/c, 6x 5 ins (15.2 x 12.2 cm.), ex-Peter Nahum at The Leicester Galleries. Photo: with thanks to The Victorian Web

However, they may have begun earlier. Although Val Prinsep recalled that on his and Burne-Jones’s first visit to Italy in 1859, ‘Ruskin in hand’, they had ‘scoffed at Sansovino’ and thought ‘A broken pediment was a thing of horror’[20], it has been suggested that the Mannerist parcel-gilt and walnut frame on a Venus of 1861 may have been acquired by Burne-Jones on the same trip, and the head of Venus painted specifically for it[21].

Andrea Mantegna (c.1431-1506), San Zeno altarpiece (Virgin and Child with saints), 1456-59, tempera on panel, 480 x 450 cm., San Zeno, Verona

During this visit to Italy, Burne-Jones went to Verona, where, in the church of San Zeno, he would have seen Mantegna’s altarpiece of the Virgin and Child with saints in its magnificent aedicular frame. This divides the continuous interior space into three with its series of attached columns, separating the Virgin in the central field from the supporting saints at the sides. It is generally agreed that the fictive tripartite frame in Burne-Jones’s great canvas of The story of Troy, begun in 1870, is based on Mantegna’s altarpiece[22].

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The story of Troy, 1870-98, o/c, 273 x 294.6 cm., Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Mantegna, San Zeno altarpiece, 1456-59, predella (detail); Burne-Jones, The story of Troy, 1870-98, predella (detail)

Burne-Jones follows Mantegna in creating a deep predella with painted scenes set between decorative dividing panels; his fictive frame is coloured as well as gilt, and the classical entablature sports a shallow-relief ‘Frieze of Babies struggling’, based on the frieze of putti decorating the internal space of Mantegna’s altarpiece. He eschued the segmental pediment and acroteria which crown Mantegna’s frame, and replaced its outer columns with square pillars, also adapted from those in the fictive architecture within Mantegna’s picture.

Mantegna, San Zeno altarpiece, 1456-59, angels (detail); Burne-Jones, The story of Troy, 1870-98, putti (detail)

This extraction of objects from within Mantegna’s pictorial space is extended to the two musical angels at the base of the Madonna’s throne: in Burne-Jones’s canvas they are multiplied to become the six ‘three-dimensional’ babies posed on the ‘altar-shelf and around the plinths[23]. Burne-Jones’s studio assistant, Thomas Rooke, indicates in his notes on the painting that it was intended to be executed as a wooden and bronze altarpiece containing painted panels: it would have been displayed on a kind of secular altar, and ‘festoons and chaplets of jewels were also to be hung from the capitals at the top, in the Crivelli manner’ [24]. If so, it may be the largest and most finished working design for a picture frame ever produced.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The triumph of Love (Fortuna; Fama; Oblivio; & Amor), 1871, watercolour & body colour, each panel roughly 12 x 6 ins incl. fictive frame, with detail of Fame, Christie’s London, 5 June 2008, lot 39

Although it was never realized in three dimensions, the Story of Troy not only provided Burne-Jones with subjects to work up into self-contained paintings, but sired a large group of Renaissance-style aedicular frames. It also led to a number of drawings and paintings which are finished with fictive borders. For instance, each of the four small studies executed in 1871 for the dividing panels of the predella – Fortune, Fame, Oblivion and Love [25] – has its own painted trompe l’oeil frame in faux stone, with the titles ‘engraved’ at the bottom, and ‘carved’ daisy paterae around the other three sides. The daisies are probably derived from those on the entablature and scrolled acroteria of the San Zeno altarpiece, which, in turn, Mantegna would have seen on the fragments of Roman antiquity which surrounded him everywhere, and were being collected by his patrons. Burne-Jones would have been quite as alive as Mantegna to the legacy of the classical past, and the possibilities of employing it in his frames to support his subjects.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Days of Creation (1872-76) in their [recoloured] original frame, illustrated in black-&-white in the catalogue of Sotheby’s sale, London, 13 June 1934, Lot 99; now as 5 separately-framed works in Harvard Art Museums (one has been stolen)

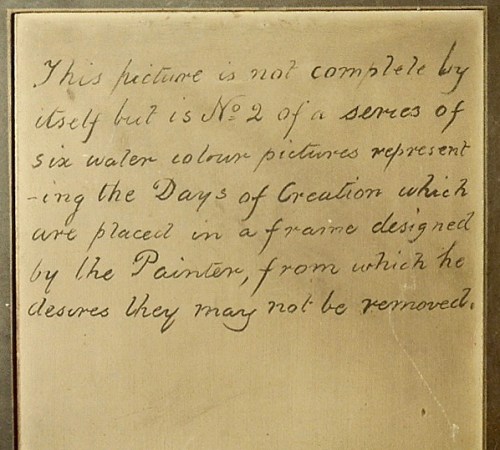

The first full-scale aedicular or ‘altarpiece’ frame used by Burne-Jones was designed for his set of six watercolours, The Days of Creation, 1872-76. It derives from The story of Troy in its use of a single housing for several panels, but it is greatly simplified. Pillars, half-columns and predella paintings are replaced by outlined panels, and in place of the ornamental frieze there is a Latin inscription; only the decorative cornice and supporting brackets are retained. This is appears to be the only one of Burne-Jones’s frames to have been noticed in contemporary reviews [26], and it is thus particularly unfortunate that when this work was bought by the American collector Grenville L. Winthrop in 1934, the panels were reframed singly in plain gilt mouldings and the original setting lost [27]. This is especially poignant in view of Burne-Jones’s own plea for the integrity of the paintings within their frame as a single work of art.

Burne-Jones,The Days of Creation, inscription on the reverse of no 2

Each panel has a hand-written inscription on the back:

‘This picture is not complete by

itself but is No. X of a series of

six water colour pictures represent

-ing the Days of Creation which

are placed in a frame designed

by the Painter, from which he

desires they may not be removed.’

This effort to ensure that frame and image remained a single unit springs from the same motive which produced so many pictures with inalienable trompe l’oeil borders, and demonstrates both the value Burne-Jones placed on the frames he chose for his paintings, and his conception of the work of art, not as the image alone, but as the image within the setting designed for it.

Frederick Hollyer (1838-1933), The garden studio at The Grange, photographed in 1887

Emery Walker (1851-1933), King Cophetua & the beggar maid, flanked by Laus Veneris and The mirror of Venus, photographed at the Burne-Jones memorial exhibition, the New Gallery, London, 1898-99, © National Portrait Gallery, London, RN50748

His concern applied equally to reproductions of his work. From about 1875 the photographers Frederick Hollyer and Emery Walker recorded his house, his studio and exhibition hangings, as well as many of his paintings and drawings [28]. The latter, photographed mostly by Hollyer and published as fine art prints, could be bought in frames related to those of the paintings, or to simpler frames used by Burne-Jones himself.

Frederick Hollyer (1838-1933), Days of Creation after Burne-Jones, post-1875, photographs in original aedicular oak frame, overall 35 x 60ins, art market, 24 June 2017

Frederick Hollyer (1838-1933), Days of Creation after Burne-Jones, c.1880, photographs on textured paper, each 20 x 7.01 ins (50.8 x 17.8 cm.), Peter Nahum at The Leicester Galleries

Frederick Hollyer (1838-1933), Days of Creation after Burne-Jones, photogravures mounted on gold card, in a carved & parcel-gilt oak frame, overall 21 ½ x 56 ins (142.5 cm. wide), art market, 8 November 2009

Thus Hollyer’s reproductions of The Days of Creation could be obtained with a dark oak aedicular frame based on the original (top image, above); in a simpler flat oak frame with parcel gilt oak mount; in a completely unadorned oak mount, or with other forms of mount to which a variety of frames might be added (second and third images, above) [29].

The Renaissance theme introduced by The story of Troy informed several different settings used by Burne-Jones for paintings from the 1870s to the 1890s. One is his own version of a late 16th-early 17th century carved and pierced Venetian style frame, used for instance for The beguiling of Merlin.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The beguiling of Merlin, 1872-77, o/c, 186 x 111 cm., in ‘swan’s head frame’, Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight

Venetian pierced frame, c.1560-80, carved poplar, 85 x 76 cm., possibly made for Tintoretto (attrib.), Portrait of a woman, Art Institute of Chicago[30]

This was probably adapted from an original seen and sketched in Venice in 1871 or 1873, such as the example above, as no frame of this type seems to have been accessible in London at the time[31]. Strikingly unlike the academic frames commonly employed during the 1870s, which tended to be ogee or concave in section with applied compo ornament, Burne-Jones’s frames have a prominent carved torus of pierced, scrolling foliage, formed of a convex shell applied over a gilded hollow. As the spectator moves before the work, light is reflected in a shifting arc from the two levels, giving a sense of movement and vitality to the painting.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Le chant d’Amour, 1868-77, o/c, 45 x 61 3/8 ins (114.3 x 155.9 cm.), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Burne-Jones used this frame pattern appropriately for his more ‘Venetian’ compositions, such as Le chant d’Amour.[32] The beguiling of Merlin excepted, these are sensuously colourful paintings, admirably complemented by their shimmering, light-filled frames. Although the carving is slightly coarse and schematic compared with that of the 16th century, it must still have presented a challenge to his 19th century framemakers.

Burne-Jones, The mill, 1870-82, o/c, V & A, detail of frame showing swan’s head

Nestling amongst the carved foliage are small swans’ heads, which may possibly be symbols of music, of Apollo or of Venus. Again excepting The beguiling of Merlin, this imagery suits many of the paintings framed in this pattern. Two of them – Laus Veneris and The mirror of Venus – were photographed in their ‘swan’s head frames’ by Emery Walker, hanging either side of King Cophetua in the 1898-99 memorial exhibition. This is the only record of the original frame of Laus Veneris, which is now in a different setting – appropriate for it but seemingly untraceable to a particular source[33].

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Perseus Cycle: The rock of doom, o/c, 1885-88, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart

The ‘swan’s head frame’ was also used for the series of paintings depicting the legend of Perseus, the existing oil paintings for which are now in the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Perseus Cycle: three designs for walls in the saloon, 4 Carlton Gardens, showing The call of Perseus; Perseus & the Graiae; Perseus & the nereids; The finding of Medusa; The death of Medusa; Perseus pursued by the Gorgons; Atlas turned to stone; The rock of doom; The court of Phineas; The baleful head; gold paint & gouache on paper; various sizes; & detail, Tate Britain

It was originally intended that there should be ten paintings; they had been commissioned by Arthur Balfour for the music room of his London house, and Burne-Jones produced a set of elaborate designs showing how the framed paintings would be integrated into the interior, including the chimneypiece and door, and how their wider setting would extend to a ground of scrolling acanthus (either of stucco or wallpaper), to be provided by Morris & Co. Sadly, this scheme was never completed, and the finished paintings in Stuttgart were framed at some point in the Venetian ‘swan’s head’ pattern. In the designs, above, however, the fully coloured paintings were to be framed in gilded and fluted mouldings – very similar in profile to the frames on the gouache cartoons for the Perseus Cycle now in Southampton (see below), but completely gilded, rather than black and parcel-gilt. The low-relief gilded and silvered images in gesso on oak panels [34], which fitted over the door and chimneypiece and in the centre of the third wall, were to have had completely plain, flat borders. Both types of frame were evidently designed to provide a resting place between the paintings and the acanthus background. It is not clear when the Stuttgart pictures were given the Renaissance-style ‘swan’s head’ frames, but presumably their pierced, scrolling pattern was a replacement for the acanthus walls in the failed commission.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The golden stairs, 1868-80, o/c, 269.2 x 116.8 cm., Tate Britain

Another very different type of Renaissance revival design produced a family of frames linked by the candelabrum ornament used to decorate them. These include versions of the Italianate cassetta (‘little box frame’), fully aedicular frames with pilasters and capitals, and a hybrid between the two. All are classicizing in structure and ornament – flat and linear with surface decoration, as opposed to the exuberant three-dimensional Venetian frames.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Wheel of Fortune, 1875-83, o/c, 200 x 100 cm., Musée d’Orsay

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), King Cophetua & the beggar maid, 1884, o/c, 293.4 x 135.9 cm., Tate Britain

Appropriately, they reflect the cooler, more classical tone of works such as The golden stairs (cassetta) and The Wheel of Fortune (cassetta with added entablature and predella panel). The frame of King Cophetua and the beggar maid (fully aedicular) is related, but on a very much grander scale, and with individually-designed details.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The legend of Briar Rose, 1885-90, comprising four large paintings (49 x 98 ¼ ins) & ten filler panels, Buscot Park, Oxfordshire

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The legend of Briar Rose: the Garden Court, from the third series of works on this subject, finished 1894, o/c, 126.3 x 237.4 cm., & detail, Bristol City Museum & Art Gallery

Burne Jones, Venus Discordia, begun 1872, 50 x 82ins, detail of frame now on this painting but made for a larger work, National Gallery of Wales, Cardiff

There are several versions of Burne-Jones’s fully aedicular frame. All of them derive from 15th century Italian models, and although some are individual designs, there is a distinct group, characterized by certain features: candelabrum ornament springing from elegant fluted urns; square capitals containing a palmette in a pointed arch with acanthus leaves; a frieze of scrolling foliage, half-flowers and berries; ogee mouldings in the base and a cornice decorated with imbricated scale patterns. Burne-Jones probably created this design for the set of four Briar Rose pictures (and the two other series of these large paintings) as well as for their supporting painted fillers which form a continuous decorative scheme, half mural, half ornamental panelling, around the saloon at Buscot Park [35]. This whole scheme, which extended from 1872 to 1890, is a projection of his ‘beautiful romantic dream of something that never was’ into a three-dimensional enclosure, which enfolds the spectator in a secular analogue of a painted Renaissance chapel where contiguous ‘windows’ open in gilded haloing frames onto celestial visions [36].

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Sibylla Delphica, c.1886, o/c, 60 1/8 x 23 ¾ ins (152.8 x 60.3 cm.), Manchester Art Gallery

Other versions of the aedicular frame have small Composite capitals and different candelabrum ornament: the identical frames of Sibylla Delphica and Caritas [37], and the monumental frame of King Cophetua amongst them. All, however, show a firmly Renaissance revival interpretation of the frame structure, in contrast to – for instance – the Neo-Greek architectural style of Leighton’s and Alma-Tadema’s aedicular frames [38], which were most suited to their purely classicizing subjects, whilst Burne-Jones’s were more versatile. Caritas, for example, is a Christianized personification, and has its significance underlined by its Renaissance ‘altarpiece’ setting; whilst the composition of King Cophetua is itself based on 15th century Italian retables [39].

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430/35-c.1494), Madonna della Rondine, post-1490, oil & egg tempera/panel, 150.5 x 107.3 cm., National Gallery, London

Emery Walker (1851-1933), King Cophetua & the beggar maid, photographed at the Burne-Jones memorial exhibition, the New Gallery, London, 1898-99, © National Portrait Gallery, London, RN50748

Emery Walker (1851-1933), King Cophetua & the beggar maid, photographed at the Burne-Jones memorial exhibition, the New Gallery, London, 1898-99, © National Portrait Gallery, London, RN50748

Indeed, one of the sources for the frame as well as the composition of Cophetua may be Crivelli’s Madonna della Rondine, which was acquired by the National Gallery, London, in 1862, together with its original aedicular frame. The Composite capitals, candelabrum ornament and pilaster plinths of this frame are echoed by those of Cophetua; and the painted frieze at the base of the Virgin’s dais seemed to have inspired the scrolling foliage on the predella of Cophetua even more closely. A playful reference to other Renaissance frames may also have inspired the three cherubs’ heads which originally adorned the predella (and have since been restored) [40].

Cophetua was a major ‘machine’, deserving a grand setting with specific additional details. Burne-Jones was a prolific (although slow-working) artist, however, and he – like Leighton and Alma-Tadema – developed his own group of ‘stock frames’ which could be adapted to large or smaller works, single paintings or series.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Pygmalion & the image: The godhead fires, 1878, o/c, 143.7 x 116.8 cm., Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

These are the Renaissance-style candelabrum frames, made either in the form of a cassetta (an oblong format with flat frieze and defining outer mouldings), or a semi-aedicular type (the cassetta with added mouldings at top and bottom, giving the effect of entablature and plinth), like the variations on The golden stairs/ Wheel of Fortune styles discussed above. They seem to have been in use from the late 1870s, probably first appearing on the second Pygmalion series of 1875-78, now in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. These have cornice and plinth mouldings applied to the basic cassetta; the pressed composition ornament already including characteristic squat fluted urns in the bottom corners, from which spring sheaves of bladelike leaves.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The golden stairs, 1868-80, o/c, 269.2 x 116.8 cm., detail of frame, Tate Britain

The design hardly varies during the 1880s and 1890s, with larger works given an outer egg-&-dart moulding for added weight. The golden stairs has already been mentioned; others include The Annunciation, 1876-79, and The Tree of Forgiveness, 1881-82, both with applied cornice and plinth. Less important pictures have blander, less defined candelabrum ornament; for example, the tondo frame for the cartoon, Dies Domini, 1880.

Different degrees of finish may, of course, be due to the involvement of different framemakers, and Burne-Jones certainly used several. The Annunciation has the label of Paul Vacani, although it gives the High Holborn address he occupied from the later 1880s until 1890, and is so far beyond the date of the painting and its exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1879 as perhaps to refer to packing, adaptation or restoration [41]. Vacani is also mentioned in one of Burne-Jones’s few recorded references to framemakers: in a letter of about 1890 to William De Morgan, he asks,

‘…do you remmember a frame i likt at your house it was a frame from florrence and was a nice one and i likt it may Mr Vacani make one lik it… [sic]’ [42]

Although Burne-Jones evidently used Vacani for a year or so around this time, there is no indication that he remained with him, or that Vacani made more than one – if indeed he made any – of the candelabrum frames.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Star of Bethlehem, c. 1887-91, watercolour & bodycolour on paper, 101 x 152 ins (256 x 386.8 cm.), and detail. Photos with thanks to Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

The frame copied from De Morgan’s original may well have been the reverse torus frame for The Star of Bethlehem, 1887-90, the huge watercolour of the Nativity commissioned by the Corporation of Birmingham and now in the Birmingham Museum. De Morgan’s wife stayed frequently in Florence, where her uncle Spencer Stanhope had settled in 1880, and both artists used frames made by local craftsmen – as did J.M. Strudwick, a one-time studio assistant of Burne-Jones’s. Many of these were torus or convex frames carved with multiple rows of ornament, very similar in kind to the frame of The Star of Bethlehem; and this is the most likely type of setting for Burne-Jones to have seen at De Morgan’s house. If he did not himself attempt to order one directly from Florence, it was probably because of transport problems, especially as he worked on a larger scale than Stanhope and Strudwick..

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Sponsa di Libano, 1891, watercolour & gouache on paper on panel, 325.7 x 158 cm., and detail, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Botticelli (workshop; 1445-1510 ) Madonna & Child, c.1490-1500, tempera on wood, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Photo: Екатерина С.

Another advantage of entrusting it to an English carver would have meant that he could order similar examples ‘off the peg’ whenever he wanted; and there are indeed related carved torus frames on paintings of the 1890s – Sponsa da Libano and Lady Windsor – which are different in kind from earlier examples. The frame of Sponsa di Libano has a large torus, occupying most of the width of the frame, and carved with a garland of foliage, fruit and flowers, bound at intervals with ribbon. This is the ornament typically used for a Renaissance tondo frame on a depiction of the Madonna and Child, which Burne-Jones would have been familiar with, having visited Italy four times in 1862 and the 1870s. It must have seemed particularly appropriate for the painting of another virginal and biblical bride, this time inspired by the Songs of songs in the Old Testament.

Burne-Jones wrote himself of the setting for The Star of Bethlehem,

‘It isn’t a wide frame, for a wide frame would dwarf the picture; I find little pictures are good in vast frames but big ones frame themselves. About all this I have used my best judgement, but the sooner I order the frame the better, for I want its horrible new glare to tone a little.’[43]

This is one of his few recorded pronouncements on the principles of picture framing. He also expressed a marked preference for glazing his pictures, writing of his disappointment that the Whitins, who commissioned Hope,

‘…have hung it up without a glass, to see it better, because of reflections in it. They could manage that by sloping it or in some way. I like a picture so much better under glass, it is like a kind of aethereal varnish. It is wonderful to me how people don’t see that a picture under glass is so much more beautiful than without it – they are so insensitive.’[44]

Others were sensitive to Burne-Jones’s care in displaying his work. In a paper on picture frames presented to the Society of Arts in 1899, Hunter Donaldson commented on the frames in the current exhibition of the Royal Academy, including designs by Leighton, Alma-Tadema, and Albert Moore, as well as Holman Hunt’s Miracle of the Sacred Fire (mentioned in note 27) [45]. He illustrated the frame of King Cophetua, and included a list of the various types of mounts employed by Burne-Jones for watercolours and drawings: ‘Some of his designs are marvels of elaboration… striking evidences of his fertility and refined taste’. Until then, mounts had not been much considered, even by those 19th century critics who were alert to contemporary framing practices. Seeing a dozen patterns of frame and mount listed and described together is certainly a revelation of what Donaldson called the artist’s ‘fertility and refined taste’, and of his care for the overall effect of colour, proportion and decoration on the works framed. Unfortunately, few of his combinations of flat unvarnished wood or dark reeded frames with lined, gilt and bevelled card mounts have survived intact, although examples can be seen in photographs by Walker and Hollyer [46].

However, at least one example survives of a particularly idiosyncratic method of mounting used by Burne-Jones. Donaldson describes it as a

‘…2 inch reeded teak-coloured oak frame, flat of 2 ½ inch light unvarnished oak, deep bevel, near which is a fine gold line, and another ¼ inch wide, outlined black.’

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Romaunt of the Rose: The heart of the Rose, 1881, black chalk & graphite on paper, 35 7/8 x 45 7/8 ins (91.1 x 116.5 cm.), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The large and elaborate drawing of The heart of the Rose (1881) retains just such a dark reeded frame and oak mount or ‘flat’ with a border of gilding lined in black, like a wash mount [47]. The warm, pale tones of the wood, set between the dark frame and the band of gilding, create a sympathetic setting for the velvety textures of the drawing, and an original alternative to a close frame [48], or a card mount. Its flaw is a tendency – as can be seen – to crack badly down the grain or at joints, which may help to explain why so few of these attractive settings have survived.

Wooden mounts and reeded, fluted or flat frames in stained, black, gilt or unvarnished wood were used by Burne-Jones throughout his career to frame watercolours and sketches, and to display his work in his studio. Their importance to him as effective elements of presentation appears in the reframing of Scenes from the life of Saint Frideswide. These cartoons for a window in Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, were painted over in oils in the 1860s, made into a screen of eight wings by Burne-Jones himself, and later bought by Myles Birket Foster. In about 1890 they were acquired by W. Graham Robertson, who wrote of them,

‘The great Frideswide screen stood in a seldom-used studio, and I finally induced Birket Foster to pass it on to me; when I detached the panels, framing each separately in a narrow band of black, under Burne-Jones’s direction.’ [49]

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Angeli ministrantes, 1878, coloured chalk on paper, 212.3 x 150.5 cm., Fitzwilliam Museum

The bands of black have two gilt flutes and a gilt bevel, and are specimens of what might be called Burne-Jones’s ‘studio frames’. Similar black frames with two or three gilt flutes were used on, for instance, the cartoons for the stained-glass windows in Salisbury Cathedral – Angeli ministrantes and Laudantes, now in the Fitzwilliam; cartoons for figures in stained glass of The Virgin and St Dorothea [50]; a triptych of cartoons in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery for a window showing The Last Judgement; and all the cartoons for the paintings in the Perseus series.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Perseus Series: The death of Medusa (II), c.1881-82, gouache on paper, 152.5 x 136.5 cm., Southampton City Art Gallery

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), Portrait of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, 1890, o/c, Royal College of Music, London

Some of the Perseus cartoons, and also finished oil paintings – The Fall of Lucifer (Robert Walker Collection, Paris) – can be seen framed in this way in photographs of Burne-Jones’s garden studio [51]. The portrait of the pianist Ignacy Paderewski has a similar black frame with a double gilt flute and a stepped profile.

The fact that Burne-Jones advised Graham Robertson on the framing of his own work indicates the value both artists put on the appropriate setting for the appreciation of a work of art. Because the Frideswide panels were originally large cartoons, altered later into paintings but not designed as works for public exhibition, they were given frames which reflected their type and status: not mere plain batons, but frames which, whilst simple and economic, had their own coherent design and proportion, where contrasting colour and geometric mouldings created a dignified but nevertheless rich effect. Similarly, the Perseus cartoons were displayed in Burne-Jones’s studio as a complete series, framed for visitors to see, but without the opulent decorative finish of works hung in the Grosvenor or New Galleries. It is possible that Burne-Jones commissioned frames of this type from the firm of Foord and Dickinson, who were, with W.A. Smith (later Smith and Uppard), the leading framemakers for the many late Victorian artists who designed their own frames.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), one of six studies for The Briar Rose series, 1889, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Six studies for the Briar Rose series, 1889, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, have flat fluted frames with a stepped bevel at the sight edge, but are gilded overall – perhaps because of the softer colouring and forms of the pictures – as the frames for the finished oil paintings in the Perseus Cycle would have been. One at least has the label of the framemakers Foord and Dickinson, 129 Wardour Street [52].

A last example of a different kind of frame – this time, a decorative inscribed border – comes from the project Burne-Jones undertook in the last two decades of his life. He had longed to create a large project in mosaic, and had even asked Ruskin to find him some suitable location; then, in 1881, G.E. Street commissioned a series of mosaics from him for the American Episcopal church of St Paul’s-within-the-Walls in Rome. Street was responsible for several Protestant churches in Italy, and had completed this one in 1876. In the 1850s both William Morris and Philip Webb, two of the founding partners along with Burne-Jones of Morris, Marshal, Faulkner & Co., had been employed by Street, and Burne-Jones produced a large number of designs for stained-glass for the firm. This direct connection must therefore have suggested that Burne-Jones was the perfect artist for the Roman mosaics, even though it was a medium he had never actually worked with; but then he had never had any training in stained-glass design before he started, so Street must have been confident that he would succeed. The pastor wanted the whole church covered in mosaic, and Burne-Jones worked on designs which would have eventually been applied both inside and out [53]. He died, however, in 1898, whilst the apse was being completed (which was done by Thomas Rooke, his assistant), and The fall of Lucifer, which would have occupied a forty foot procession of blue-green exiled angels, only exists as a cartoon.

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The fall of Lucifer, 1894, gouache & gold paint on paper, 245 x 118 cm., collection of Andrew Lloyd Webber

The designing of stained-glass and tapestries is decorative work and therefore different in kind from representational painting, where volume and spatial depth (or its illusion) is a particular consideration. Applied art is flat; it sits on the surface of walls without piercing them with windows onto other realities. The fall of Lucifer is extremely flat; the procession of angels hardly recedes at all, winding down the picture plane in a waterfall of armour and banners from the door of Heaven, which is surprisingly close to the spectator. This flatness is enhanced by the integral border, created as a thick band of gold, the inscription it carries appearing to be physically engraved into the surface (a quotation in Latin from Revelation 12: 7-12 [54]). The fact that this inscribed border is part of the pictorial surface, and also that it is broken on the top right corner, both reinforce the decorative flatness of the winding trail of defeated angels. It is a painting which manages to be both an arrangement of abstract patterns and a queue of realistic knights breathing a profound melancholy.

The number and variety of frame types used by Burne-Jones throughout his career are impressive witnesses to his passionate determination, not only to realize his visions of another world which ‘no one can define, or remember, only desire’ [55], but also to give those visions settings which would provide their perfect context. Some frames floated his work free of the studio wall, so that he and his fellow artists could appreciate the stage they represented on the voyage to the finished painting; some held smaller works like the settings of miniatures and jewels; some were great ornamental doorways decorated in the language of other civilizations, through which the spectator might enter the artist’s vision.

The constant presence of the framemaker in Burne-Jones’s consciousness is evident in a remark he made in the last year of his life:

‘Asked whether he ever tried to imagine he was painting on a wall whilst working at his pictures in the studio, he said: “That and all kinds of things I try and comfort my poor little old self with. But all the same I’m not painting on a wall, or if I am, Smith and Uppard will come and carry it away presently”.’ [56]

*************************************************

Edward Burne-Jones (1833-98), The Perseus Series: Perseus & the Graiae, 1877, oak panel, with gesso, silver & gold leaf, 170.2 x 153.2 cm., National Museum of Wales, Cardiff

*************************************************

[1] Georgiana Burne-Jones, Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, London, 1904, vol. I, plate opposite p. 1

[2] L. Roberts, ‘Nineteenth century English picture frames II: The Victorian High Renaissance’, International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship, V, 1986, p. 278.

[3] See, for example, the frame for the second version of the Adoration of the shepherds triptych illustrated here – a frame of 1861 decorated in the early style of Burne-Jones and Morris. See also E.A. Tunstall & A. Kerr, ‘The Painted Room at the Queen’s College, Oxford’, The Burlington Magazine, LXXXII, 1943, pp. 42-47, ill. Burne-Jones and Morris are said to have painted this room in 1856: figurative and decorative panels are ‘framed’ with undulating zoomorphic foliage; a painted beam anticipates the design of Burne-Jones’s ‘swan’s head frame’; see below.

[4] For their letters discussing frames, see O. Doughty & J.R. Wahl: Letters of D.G. Rossetti, Oxford, 1965, especially those of 1861, 1864 and 1867.

[5] Georgiana Burne-Jones, op. cit., I, p. 214

[6] For instance, Princess Sabra, c.1865, Sotheby’s, London, 11 November 1998; the study of the Beggar Maid (c.1880) for King Cophetua, Tate Britain; and the study (1890-91) for The Attainment: the Vision of the Grail, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery. Rossetti used the same triple bay leaf moulding for The blue closet, The tune of seven towers, and The wedding of St George and Princess Sabra, all 1857, all once owned by William Morris, and all now Tate Britain

[7] Georgiana Burne-Jones, ibid.

[8] Cupid’s forge, 1861, ex-Peter Nahum, The Leicester Galleries, respectively.

[9] The backgammon players, 1862-63, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

[10] Cinderella, 1863, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

[11] 1863, private collection. Ruskin senior wrote of this, ‘I was charmed – excited – exalted by it, and I doubly thank Mr Jones for getting me a frame in such fine taste. Would he kindly tell the frame-maker to bring his account to No. 7, Billiter Street, City, for payment.’ Geogiana Burne-Jones, op. cit., I, p. 261

[12] The Nativity, Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford; commissioned in 1863 by the Dalziell brothers

[13] See R. Parkinson, ‘Two early altar-pieces by Burne-Jones’, Apollo, November 1975, pp. 320-23 (frames not illustrated)

[14] Information kindly supplied by John Anderson

[15] Brown and Rossetti used these small roundels on their earlier frames; they were copied by their followers, by various late Victorian artists, and then by dealers wishing to provide appropriate settings for Pre-Raphaelite work

[16] The details and date of this frame appear in a letter from Brown to his patron James Leathart: ‘…I am glad that the frame of King Lear is so much to your taste – I had told Green to employ all or any of my patterns, as it might spread a taste for a different kind of thing from the debased article now in use…’, 8 February 1863; information from Mary Bennett

[17] Rossetti objected to Brown in 1861 that ‘Dixon [a protégé of Ruskin] had the coolness to write to me the other day, wanting the proper measurements and mode of making for oak frames!’ Letters of D. G. Rossetti, op. cit., note 13 to no 392, 14 August 1861

[18] Rossetti’s two panels, painted in 1859, were taken from a cupboard decorated for Morris and framed as a diptych in 1863; see Alastair Grieve, ‘The applied art of D.G. Rossetti: 1. His picture-frames’, The Burlington Magazine, CXV, 1973, pp. 16ff

[19] Information from Tamsin Daniel

[20] V. Prinsep, ‘An artist’s life in Italy in 1860’, Magazine of Art, 1904, p. 417, quoted by S. Wildman & J. Christian, eds, Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian artist-dreamer, exh. cat., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, and Musée d’Orsay, Paris; New York, 1998, p. 80

[21] Peter Nahum, in Burne-Jones, the Pre-Raphaelites and their century, exh. cat., Peter Nahum Gallery, London, 1989, no. 47

[22] See M. Harrison & B. Waters, Burne-Jones, London, 1979, p. 103

[23] This was possibly designed as a guard against the canvas being cut up into its separate parts.

[24] Wildman & Christian, op. cit., p. 152

[25] Ex-Watts Gallery, Compton; original frame and mount. For illustrations of other fictive frames, see Georgiana Burne-Jones, op. cit., II, p. 60; there are many other examples

[26] See William Michael Rossetti’s review of the first Grosvenor Gallery exhibition: ‘The Days of Creation… six subjects in a common frame of ornamental design’ (The Academy, 5 May 1877, pp. 396-97; and idem, on the sale of ‘The Graham Collection’ at Christie’s, Saturday 3rd April 1886: ‘The beautiful decorative set of six panels… representing the six days of Creation, which was extremely well seen of the side wall of the room in its fine ornamental frame’ (The Times, 5 April 1886, p. 12). See also L. Hunter Donaldson, ‘Picture frames’, Journal of the Society of Arts, II, June 1899, pp. 595-610; information with thanks to Jacob Simon

[27] Winthrop also reframed Holman Hunt’s Miracle of the sacred fire, and probably one version of his Triumph of the Innocents too – these original frames, designed by the artist, have been lost along with the frame of The Days of Creation.

[28] Hollyer’s photographs (mainly in private collections) show Burne-Jones’s paintings, and interiors of his house and studio in Fulham, complete with frames. Emery Walker also photographed framed works, and the interiors of the New Gallery during the memorial exhibition of 1898-99 (a collection is in the National Portrait Gallery, London). The output of both men provides an invaluable record of Burne-Jones’s original frames.

[29] Another example of the first type was also sold by Christie’s, London, 11 June 1993, lot 54a. These frames would almost certainly have been designed, supervised, or at least suggested by the artist. For information on the second type, I am indebted to Rupert Maas; and for the fourth, see also Christie’s, London, 4th November 1994, lot 70. For a set of dark flat frames with applied foliate decoration (The legend of the Briar Rose, published by Thomas Agnew & Sons, 1890), see Peter Cannon-Brookes, ‘Picture framing: framing Burne-Jones’, Museum Management and Curatorship, XII, March 1993, pp. 111-12. Uniquely, a drawing exists for the latter in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, a sketch of almost identical scrolling half-leaves, presumably architectural in origin, although closely resembling a frame design by Holman Hunt; see Mary Bennett, Footnotes to the Holman Hunt exhibition’, Liverpool Bulletin, XIII, 1968-70, pp. 26-64

[30] See Richard Brettell & Steven Starling, The art of the edge: European frames 1300-1900, exh. cat., Art Institute of Chicago, 1986, no 14, where this frame is illustrated; and Claus Grimm, Alte Bilderrahmen, Munich, 1978, fig. 190, for another example.

[31] The only frame of this type in the National Gallery, on Titian’s Holy Family with a shepherd, acquired in 1831, was not applied to the painting until the 1960s (information from John England).

[32] Also Laus Veneris, 1873-78, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle – now reframed; The mirror of Venus, 1873-77, Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, and The mill, 1870-82, Victoria & Albert Museum (as in detail of frame illustrated)

[33] See Wildman & Christian, op. cit., p. 167. At the time of the 1898-99 exhibition, Laus Veneris belonged to Sir William Agnew; it remained in the Agnew family until 1957, when it passed to Huntington Hartford; in 1971 it was bought by Agnew’s, and sold to the Laing Gallery in 1972. There is no record of the change of frame, and the ‘new’ setting has been assessed as contemporary with the painting by conservators at the Laing. It is a Baroque revival frame, the frieze painted black and decorated with an imbricated scale pattern in sgraffito, and with symbols scratched through the paint into the gold leaf beneath – hearts, doves, a sunflower, handglasses reflecting a face, Tudor roses, rabbits, scallop shells, gimbel rings, dolphins and poppies – all attributes of Venus.

It may possibly have been executed by Burne-Jones’s assistant, Thomas Rooke, for the Agnews, but no evidence for this has emerged.

[34] The only finished gesso and oak panel is now in the National Gallery of Wales, in Cardiff

[35] There are identical frames on The Briar Rose: The Council Chamber, 1872-92, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington; Love leading the pilgrim, 1877-96/07, Tate Britain, London; The wizard, c.1891-98, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery; and Venus Discordia, 1872-73, National Museum & Gallery of Wales, Cardiff: this frame is an adaptation.

[36] For the ‘dream’ see Harrison & Waters, op. cit., p. 157. Burne-Jones may have been inspired in this and his other decorative schemes by Italian Renaissance interiors which we know he saw, in which pictures and frames are combined in a continuous inner shell; this needs further investigation.

[37] Caritas, watercolour, 1867 (but worked on again in 1885 after its purchase by Lord Wantage, for whom it was almost certainly reframed), gouache & gold, 59 ¾ x 26 ¾ ins (152 x 68.5 cm.), is now in the collection of Andrew Lloyd-Webber, so it would be pointless even to try asking for an image. However, it can be see unframed on the Art Renewal website , and as a small framed presence standing on the floor on the left at the back of Burne-Jones’s garden studio, in the photograph by Frederick Hollyer illustrated earlier in this article.

[38] For Alma-Tadema’s frames, see ‘Lawrence Alma-Tadema: At Home in Antiquity: a review of the exhibition, with a general note on his frames’; for Leighton’s, see a photo of his studio, Leighton House. Burne-Jones’s ornament is almost solely Renaissance in type, although the anthemia on the frieze and capitals of King Cophetua might be seen as more in the style of Leighton.

[39] See Wildman & Christian, op. cit., p. 253, where they cite Mantegna’s Madonna della Vittoria in the Louvre and Crivelli’s Annunciation in the National Gallery as examples.

[40] The frame of Cophetua was enlarged to take a glazing door, probably shortly after the 1898-99 memorial exhibition, at which point the slightly extended predella was given an extra cherub’s head. The frame has now been returned to its original appearance; see ‘Restoring a Pre-Raphaelite frame’

[41] ‘Paul Vacani, 22 Dean St., High Holborn’; noted in E. Morris, Victorian and Edwardian paintings in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, London, 1994, vol. I, p. 13

[42] A.M.W. Stirling, William De Morgan and his wife, London, 1922, p. 71

[43] Georgiana Burne-Jones, op. cit., II, p. 214

[44] Ibid., p. 306. The Whitins of Whitinsville, MA, bought the 1896 version of Hope, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It has a ‘Watts’ frame.

[45] L. Hunter Donaldson, ‘Picture frames’, Journal of the Society of Arts, II, June 1899, pp. 595-610 (information from Jacob Simon).

[46] Iris & Tarnus and Aeneas & the Harpies, both pencil drawings of 1873, appear in an Emery Walker negative, National Portrait Gallery, London. Plainer mounts appear in Walker’s photographs of Georgiana Burne-Jones and her grand-daughter at Rottingdean, and in Hollyer’s photos of The Grange.

[47] Wooden mounts can also be seen in Walker’s photographs of Virgil & the muse and The guardian angel of c.1874 or later, National Portrait Gallery. A sketch for The sirens, c.1890, still had its wooden mount when sold at Sotheby’s, London, 3 November 1993, lot 201. Frances Graham, 1879, private collection, which originally had a similar mount, has unfortunately been reframed.

[48] The close frame is an 18th and early 19th century method of framing watercolours, the frame being ‘close’ to the image with no intervening mount.

[49] W. Graham Robertson, Time was, London, 1931, p. 282

[50] Sotheby’s, London, 24 October 1978, lot 4

[51] J. Cartwright, ‘The life and work of Sir Edward Burne-Jones’, Art Annual, XI, 1894, bound into Art Annuals, 1891-96, pp. 30-31

[52] See Stephen Wildman, Visions of love and life: Pre-Raphaelite art from the Birmingham Collection, Alexandria VA, 1995.

[53] Claire Ptaschinski, Edward Burne-Jones, G. E. Street, and the American church in Rome, MA thesis, Texas Christian University, 2013, p. 2

[54] King James Bible: ‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels,

And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven.

And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.

And I heard a loud voice saying in heaven, Now is come salvation, and strength, and the kingdom of our God, and the power of his Christ: for the accuser of our brethren is cast down, which accused them before our God day and night.

And they overcame him by the blood of the Lamb, and by the word of their testimony; and they loved not their lives unto the death.

Therefore rejoice, ye heavens, and ye that dwell in them. Woe to the inhabiters of the earth and of the sea! for the devil is come down unto you, having great wrath, because he knoweth that he hath but a short time.’

[55] See Harrison & Waters, op. cit., p. 157

[56] Georgiana Burne-Jones, op. cit., II, p. 334. ‘Smith and Uppard’ was the latest incarnation of W.A. Smith’s business (originally Joseph Green). In 1890 Smith took Uppard into partnership, and in 1899 the business was taken over by James Bourlet. See W.A. Smith on the NPG Directory of British picture framemakers.